6. Competencies

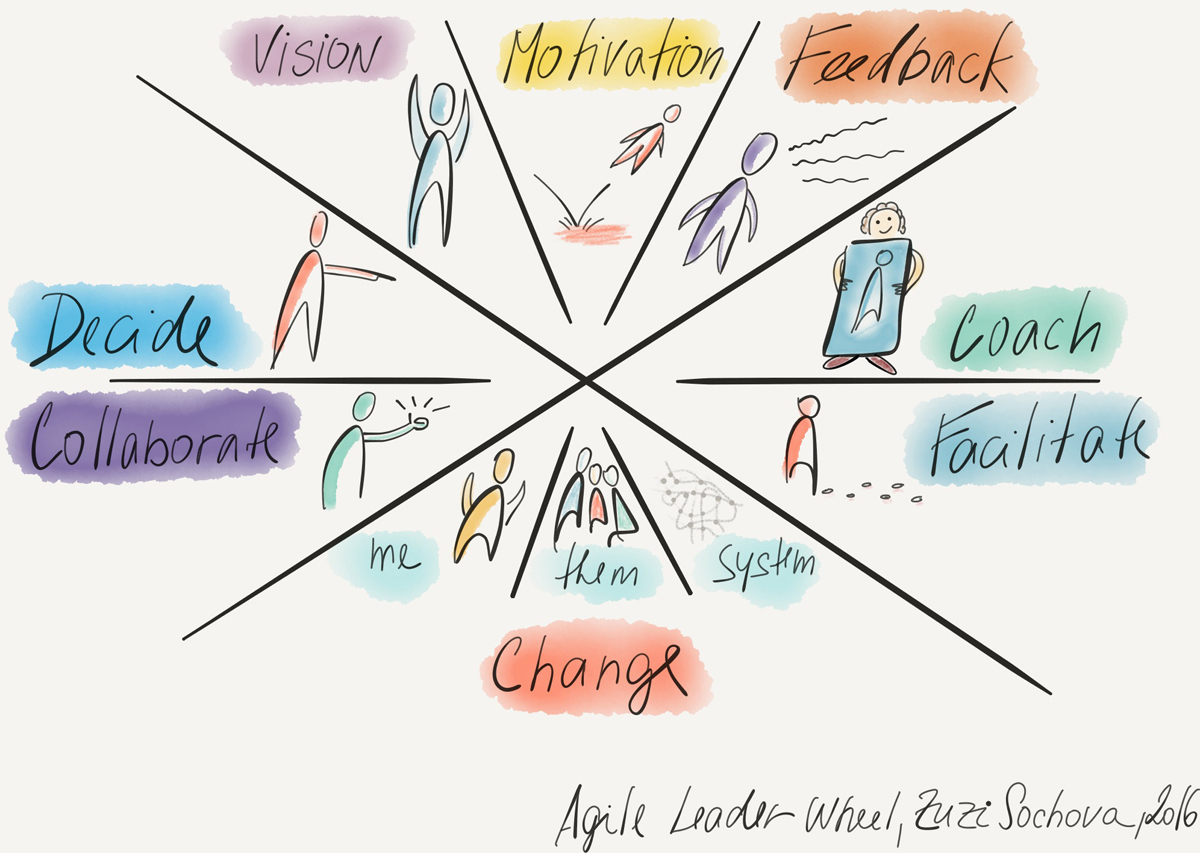

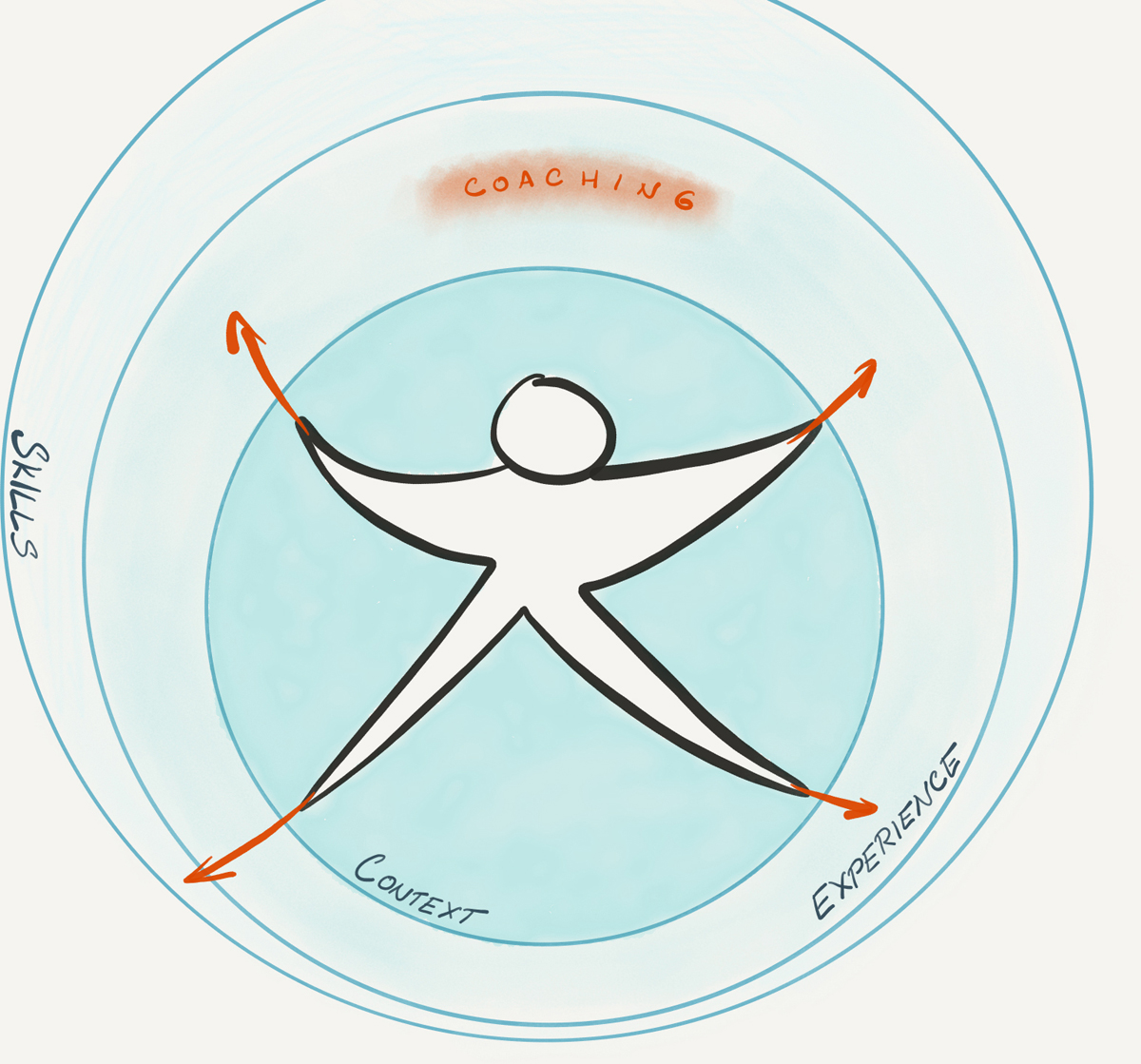

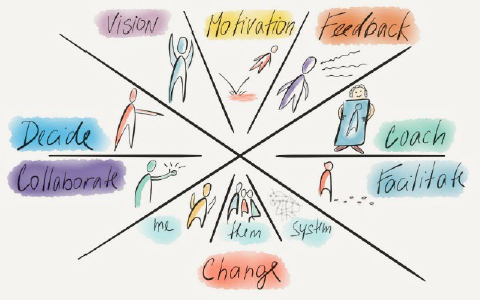

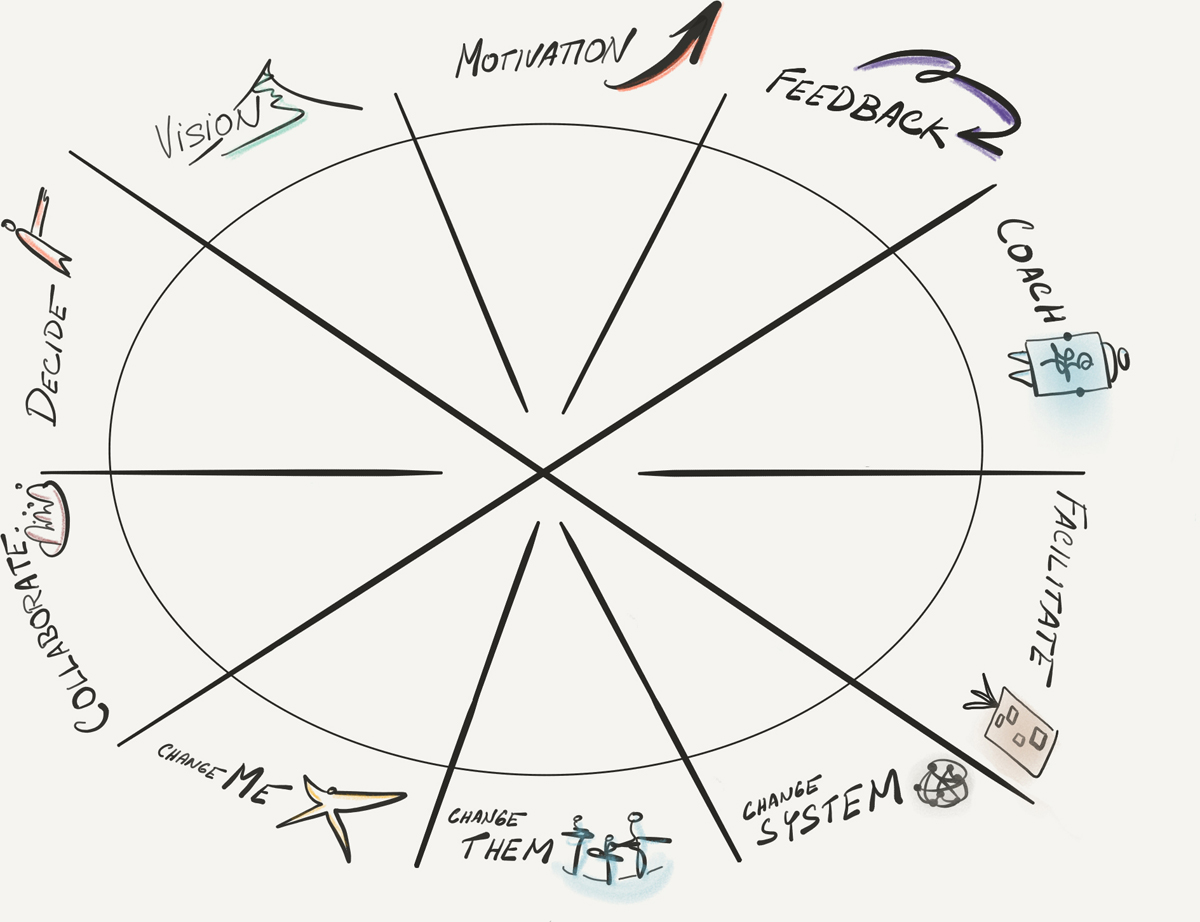

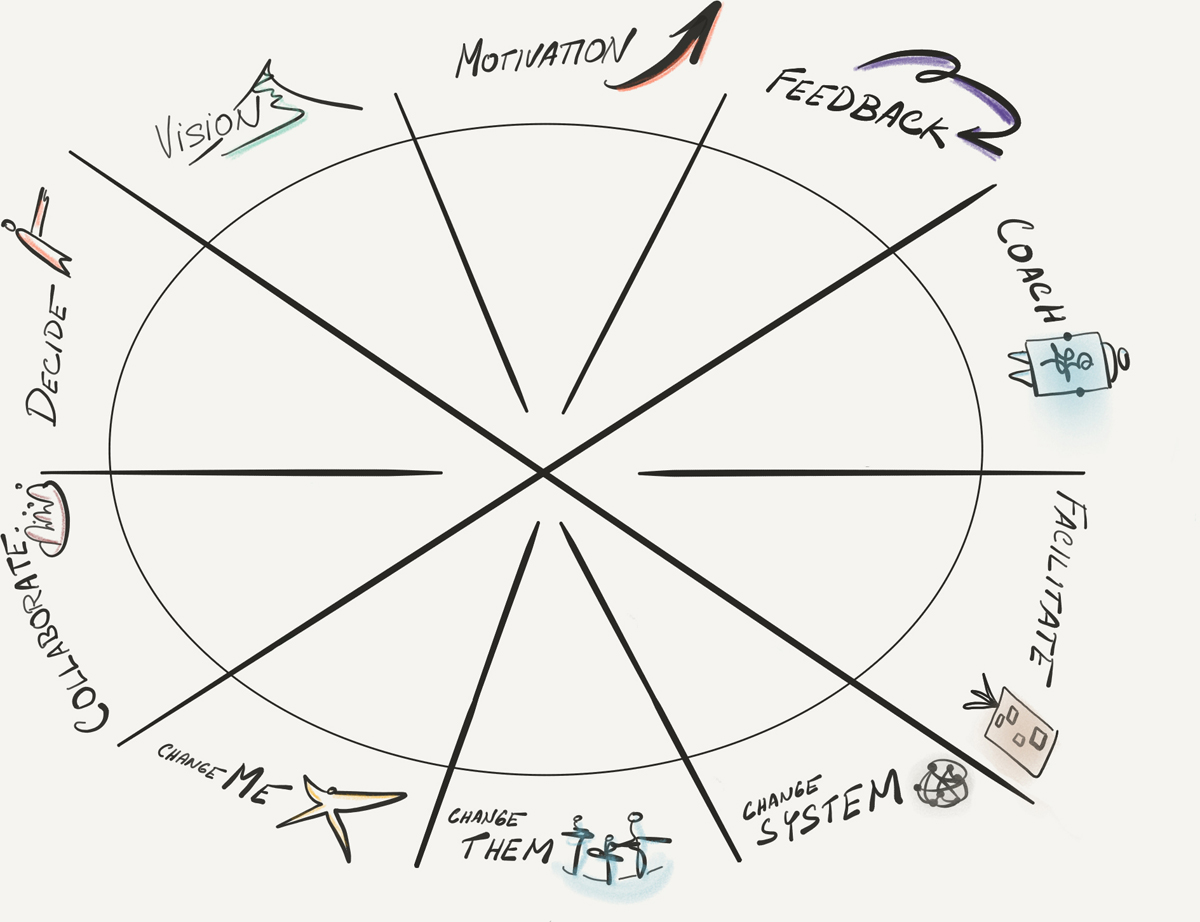

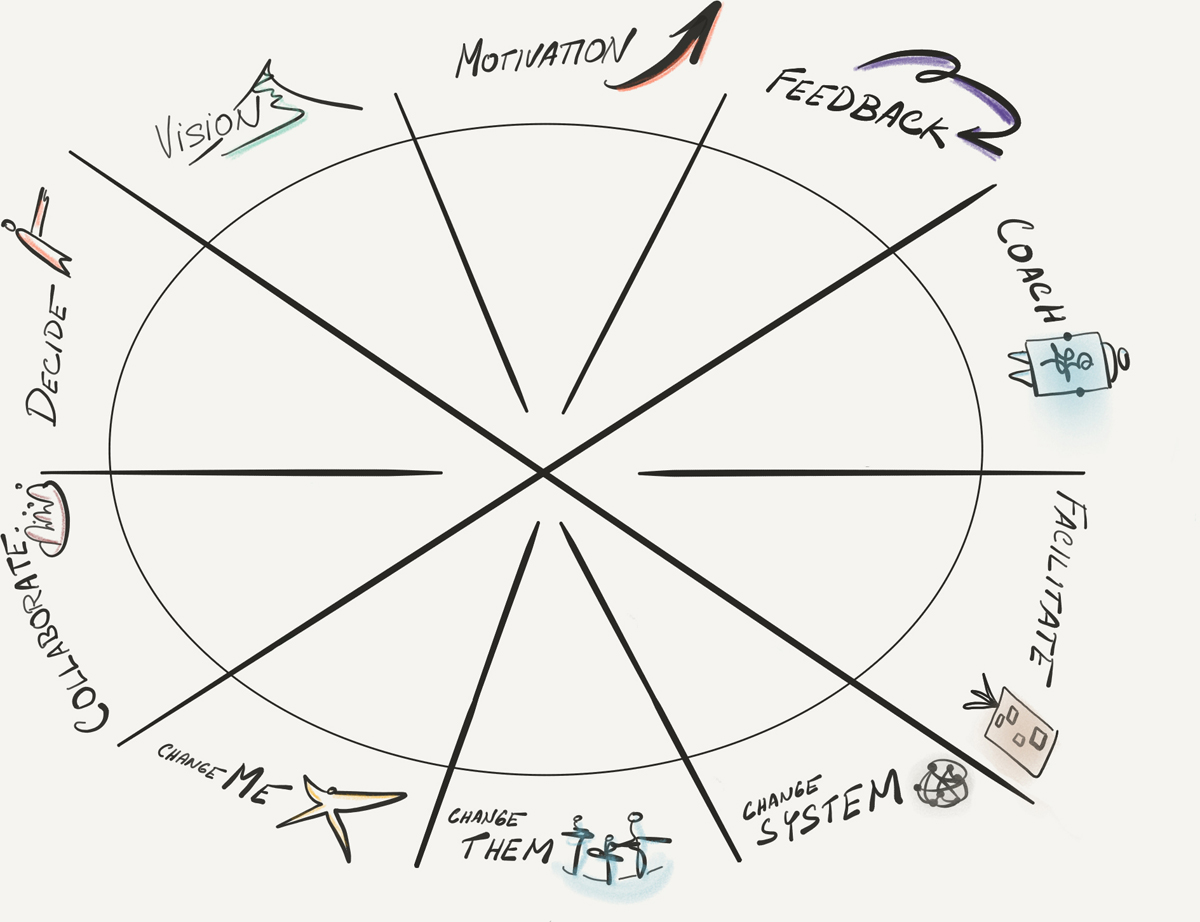

Great agile leaders have four core competencies: they can create a vision, enhance motivation, get feedback, and implement change. They also need to have the supporting competencies of decision making, collaboration, facilitation, and coaching. However, great agile leaders are not born this way—they are constantly developing these competencies. Being an agile leader is a journey, and no matter how great are you now, there is always a better way.

The Agile Leader Competencies Map is a good visualization tool that helps agile leaders to understand what are they good at and what they might need to improve.

Vision and Purpose

The vision is the driving engine for success. It’s not necessarily related to the products but to the organization itself. You can start by asking these questions: What is my dream? Who are we, and who are we not? Where do we want to go, and why? What would happen if we get there? How would it feel? What would be different? What would happen if we don’t make it—would anyone miss it? Those are just a few coaching questions that can help you articulate your vision.

You might argue that there are thousands of theories and articles written on how to come up with a great vision. However, most of them start from a very traditional mindset and are not very helpful in an agile space. They are too focused on measures and hard goals, missing the essence of necessity and emotional intelligence, and they often lead to a generic vision that everyone ignores and no one really understands or feels inspired by. Maybe that’s the reason I’d rather use the word dream instead of vision. A dream has an essence of unknown mystery, there is positivity hardcoded inside it, and it’s inspiring. Don’t be afraid to approach the visioning process differently. Be creative. You can start by drawing a picture or coming up with a metaphor. Make it a team effort. Refining the vision for the whole team or organization is never a task for one individual. The whole team needs to own it, they need to believe it, they need to want to be a part of it. That’s the energy you need to generate. It brings innovative thinking, creativity, and empowerment when people start offering help and ideas and are ready to sacrifice personal goals in exchange for being a part of something bigger.

I remember the time at my organization when we were trying to recreate the purpose of the organization, to revitalize its spirit. We looked again and again at the empty slogans framed on the walls and featured on our website: “Added value solutions.” But no one had ever explained the mission statement to us. We even went back to our founders and asked them. They felt confused. “Why are you asking? Isn’t that clear from what we do?” they asked. No, it was not clear, at least not to us. We realized we needed to recreate it and make it come alive, so that people would feel motivated and inspired by it and live and work in accordance with it. That shift was interesting, as I would have thought at that time that someone needed to explain to us what the original purpose was. But there was no need—it was in the air, hidden in the roots of who we were, and all we had to do was pay attention, be good listeners and observers. We had to connect the dots and listen to stories. It didn’t even take long. All we did was talk about it and ask why.

Don’t be afraid to look to dreams and metaphors when creating a vision. There was no magic in our pursuit of the organizational purpose, no exact process—only constant focus on what connected us and the essence of the value we created together. The organizational purpose is not created in any presentation; it’s not about hard measures either. It’s melted through the three levels of reality: from the sentient essence level to the dreaming level and back to the consensus reality. In about a month, we had come up with a solid explanation for the employees, tested on several occasions and in conversations. We had a great story to tell new people, a story attractive enough that they wanted to join us and solid enough that it led their first steps as employees. We didn’t change the original vision statement—we just reinvented it, woke it from a deep sleep, and made it live again. The “Added value solution” statement became meaningful after all. It stirred up new energy, and we changed the way the company operated. We put the focus on being proactive, on creativity, and on strong customer focus. Rather than just delivering, we worked to help our customers as our partners. By reconnecting to our purpose, we reenergized the organization and set it on track for a better future. It was quite magical.

A good purpose balances the needs of customers, employees, and shareholders. The great agile leaders are never focused on only one group of people in this virtuous circle—they all need to be in balance. Some people can argue that agile focuses on customers first, and by doing so, it defines the value employees need to deliver, get paid for, and thus satisfy the shareholders. Others would say that Agile focuses on employees first and motivates them to come up with creative and innovative solutions to satisfy customers, get paid for, and make shareholders happy. It’s a bit like a chicken-and-egg problem. As usual, all of those questions are wrong from a holistic perspective and can only help in the short term. In other words, focusing on the nodes in a virtuous circle can only address the symptoms of a bigger problem in the middle. With a strong purpose, the debate about where to focus is gone. Indeed—we focus on the purpose. The rest will sort itself out.

Which statement best describes the current situation at your company?

When you share with others what the purpose of your company is, . . .

A. They are not very enthusiastic about it; they ask you if yours is a good job and move the conversation elsewhere.

B. They are very attracted to the idea, want to know more about it, and feel you are lucky to work there.

If the company were to close tomorrow, . . .

A. Customers would move on to a different product or service and forget about it.

B. Customers would miss it.

When you ask employees what they are doing in the organization, . . .

A. They focus on their role and siloed work (e.g., writing code, testing, creating a design).

B. They refer to the value and to the business or organizational purpose (e.g., to help people to invest better, to connect organizations, to help cure cancer).

Evaluate your answers. You get one point for each B answer.

If you got zero points in the preceding exercise, your organization is starving for purpose clarity and is waiting for someone to pull it out of thin air. I strongly believe there is no organization without a purpose. In most cases, it was simply forgotten, lost in the piles of day-to-day tasks and issues, the processes, the change initiatives, the acquisitions. And time plays a role too—it could be that today no one knows anymore what the purpose used to be when the organization started. It’s good to go back in time and understand our roots. What is our legacy? Who are our founders, and what kind of dreams inspired the foundation of our organization? What is the organizational myth? When you start asking those questions in such organizations, you might get responses like, “Here is the vision and mission statement; you can find it in this presentation” or “We don’t have time for this. There is a lot of work to be done.” No one feels motivated by the purpose, so people turn their attention toward their tasks, which at least are clear, and toward the job that needs to be done.

On the other end of the spectrum, if you get all three points, you are lucky, as you work for one of the very few organizations that actually have a purpose. People feel strong energy and fulfillment. Such organizations are more focused, more creative, more innovative—and they are ready for organizational agility at the full scale.

Three Levels of Reality

The three levels of reality [Mindell_nd] describe what the visioning process should cover. In order to create an appealing vision, you need to go through all three levels of reality: sentient essence level, dreaming level, and consensus reality level. It’s a very powerful concept, as it opens a whole new world and brings creativity and emotions into the visioning process. Traditional organizations were focused on goals and objectives and hard metrics: “Become a leader on the marker” or “Be the best retail service” or “Provide high-quality products while doing our business in a socially responsible and environmentally sustainable manner.” The real organizational purpose is more than that: It has authenticity. It brings emotions. It’s a heartbeat of the organization, and it gives organizations a reason why it exists. We keep ourselves too much in the consensus reality level, trying to make everything predictable, measurable, and exact.

The three levels of reality model helps us to do the exact opposite and start in the sentient essence, where it’s all about feelings, energy, and spirit. That’s where the culture is born, that’s where the vision generates emotions and develops its own soul. It’s a level of describing metaphors, hopes, and desires. Don’t rush it. Stay here exploring this level for a while. As an example, you can ask some of these questions1 to explore the sentient essence bit more: What attracted you in the very first moments? What did you first notice/feel/experience? and What are the metaphors describing your early connection?

Only when you’ve spent a lot of time here does the essence create enough inputs for the dreaming level. The dreaming level is all about exploring possibilities and options. As the name suggests, it’s about what you want, your desires and dreams. As an example, you can ask some of these questions: What actual dreams do you have? What are your fantasies or hopes? and What are your fears? It’s where the team and collaboration are grounded. It’s the level where the essence is transformed and acquires more factual characteristics. It’s still quite abstract, but it gradually becomes more tangible.

Finally, the consensus reality makes the purpose real and brings it back to our day-to-day reality. As an example, you can ask some of these questions: Who are we? What do we want to achieve? What are our values? and What are the circumstances? The answers will be very different if you let them emerge organically by going from sentient essence through dreaming. It is more encouraging, more challenging, more motivating than the traditional process of staying only in the consensus reality. We are going to use the three levels of reality in some of the techniques described in the following sections, so you can see how to navigate through them and how this concept can be useful in creating a purpose.

High Dream and Low Dream

One of the techniques that helps to raise your awareness of your dreams is a High Dream/Low Dream exercise [CRR19]. High dreams are your purest wishes, when all of your secret hopes come true, while low dreams are limited by your fears. Low dreams are not necessarily bad—they just reflect some of your fears. In this concept, we focus on raising awareness of both kinds of dreams by using the three levels of reality.

To put it another way, the high dream and the low dreams are a good platform for you to rethink where you are and where you want to be and to create a list of actions you can take to help the organization to live its highest dream.

Using the three levels of reality as a landscape to navigate through, do the following:

• First focus on your high dream for the organization. What is it? What does it look like? What makes it important? Make a few notes.

• Then turn your attention toward your low dream and think about what it may look like if things go wrong. What does it look like? How does it feel? Make a few notes.

• Then think about the factors that might contribute to making the low dream a reality and note them.

• Finally, think about what supports your high dream and what actions you can take so that the organization moves closer to that high dream.

Bringing Down the Vision

One of my favorite tools for helping an organization to recreate or reconnect with the original organization vision is based on the ORSC exercise Bringing Down the Vision. It’s a method of facilitating a large group visioning process that uses the three levels of reality model [CRR19]. It expects you to have decent experience with system coaching and facilitation of large groups, but the results are outstanding. I use this tool for product visions, organization visions, alignment around roles and expectations, and also for communities that need to find alignment around their vision. You can give it a timeframe and ask where participants want to be in five or ten years from now, or just make it about the ideal organization, product, or situation.

Let me share an example of what the process can look like.2 This example is from a community meetup where we searched for alignment around our vision and wanted to activate the community. The leading question was What is the future of Agile—where do you see Agile in five years from now?

Phase 1: My Metaphor

The whole process starts at the individual level, where every person is guided by the facilitator through the three levels of reality and creates a metaphoric image of the organization step by step. Always give people enough time to create that image in their heads and to reproduce it on paper. For example, you can start with the following coaching questions to explore the sentient essence level [CRR19]: Imagine your organization as a real or imaginary creature. What does it feel? What is it like? What are its needs and challenges? In what ways is it healthy and thriving? Always give people some time to consider their imaginary visualization and to make a few notes and create drawings. Pictures are always better than text, so encourage people to draw their images. There is no need for perfection. Actually, the simplest images are usually the best.

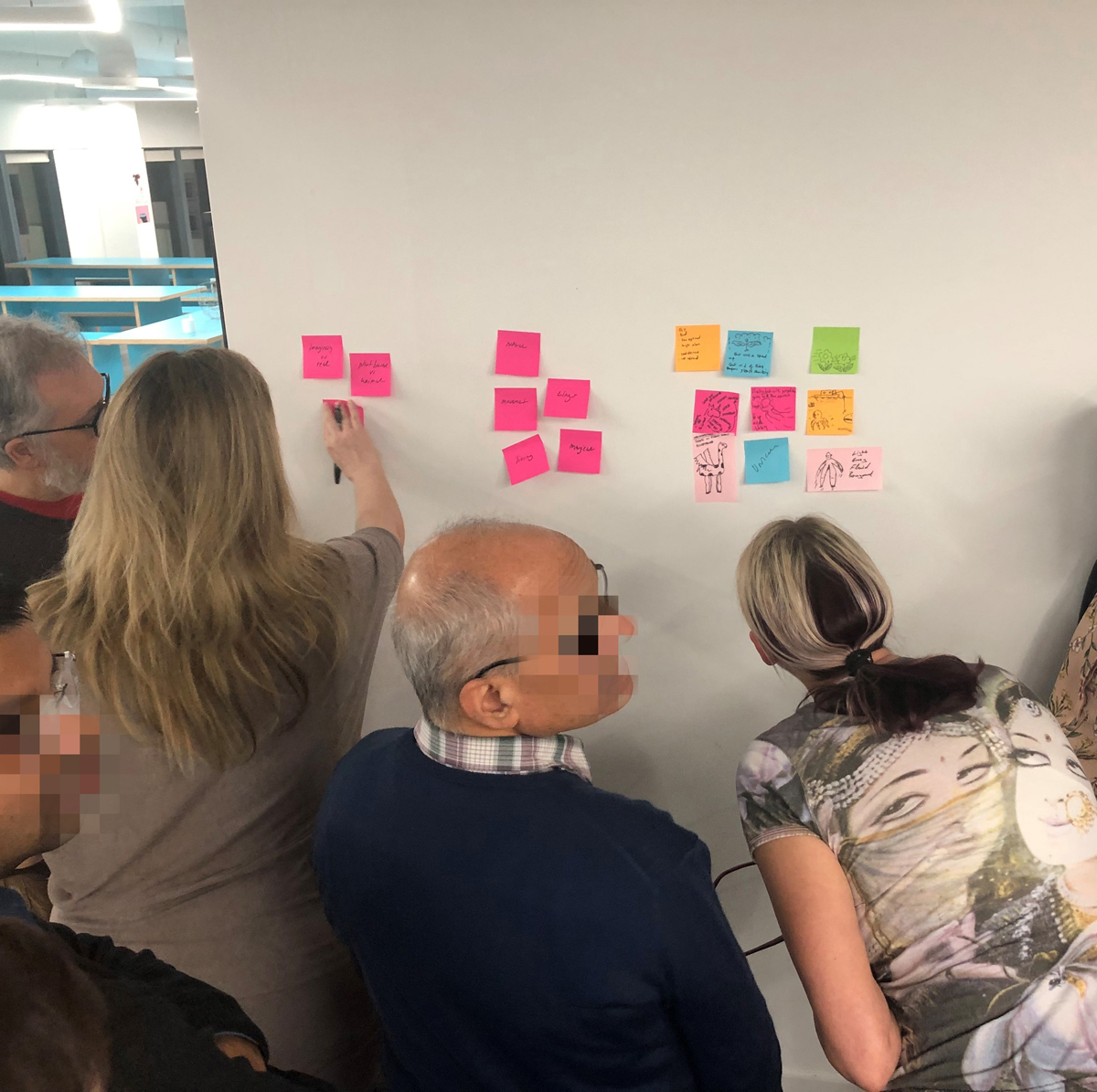

Phase 2: Metaphor Sharing

When people are done with their individual metaphors, they form small teams and share what kind of visualization they created and explain what it means to them. Teams need to be as cross-functional and diverse as possible to see different perspectives. Facilitators should make sure that the conversation is respectful to the different angles and that participants are good listeners. Curiosity is the best friend here. The more curious people are about others’ metaphors, the easier the next steps will be and the better results they will achieve from the whole exercise.

Phase 3: Team Metaphor

Now, once people have introduced their images to one other, they start to see if there are any similarities or differences and to identify the organization’s strengths, challenges, and needs. From their conversations, they search for alignment. They try to create another metaphor that embraces important aspects from all of their individual creatures. They visualize, investigate it, describe it, and are ready to share the outcome with the other teams so they can merge the essences of all the metaphors and dreams. There is no hurry to finalize the description. This may come later. But this process feeds the organizational vision like nothing else.

The phase could be repeated in a World Café format (see Chapter 11) with the intention of getting alignment from the larger group, to make it visual on a wall, and for the group to vote on the different aspects. There is no limit to the creativity. However, the basic agile values of respect, openness, focus, commitment, and courage are crucial to the success of the exercise.

Phase 4: Actions

This phase brings the whole conversation back to the consensus reality. First the teams brainstorm steps they can take to help the organization to get closer to the dream they’ve identified, and then they agree on a couple of actions they are taking back. As in the retrospective, we are not looking for any huge items; instead we care about small actionable items we can take as a next iteration of experiments.

Phase 5: Sharing

The last step is sharing. At the very end, all of the teams share their outcomes from the steps with the whole group in order to merge the essences of all the metaphors and dreams. The entire process is finished by sharing the actions and commitments with everybody to promote transparency and manage the expectations of what’s next.

As you might see, the entire process uses the power of metaphor and guides you through the three levels of reality. It is very different from the typical corporate conversations about vision, strategic plans, and goals and objectives. It uses the right brain to generate creativity in the sentient essence level. It is inspirational at the dreaming level and helps people to reconnect with the values and emotional relationships. Finally, it allows you to melt down all that inspiration into a consensus reality and to create tangible outcomes.

Motivation

The second segment of the Agile Leader Competencies Map is motivation. The nature of motivation is different in an agile world. It relies on the power of motivation driven by autonomy and a sense of purpose. “Most people are not inspired by logic alone but rather by fundamental desire to contribute to a larger case” [Kotter_nd]. The key part of motivation is related to the overall purpose. If you do the vision right and create an emotional connection to the purpose, the energy will emerge by itself and you won’t need to do much more to increase motivation. Teams will live by the vision and do their best to achieve it. On the other hand, if the vision is unclear, otherwise creative and intelligent people turn their focus toward delivering isolated micro tasks, as those are the only clear points in a very unpredictable, unclear world, and they become demotivated or at least quite disengaged. In such an environment, some would say, “People need clear KPIs, so they know what to do,” “We need to track what everyone is doing to make sure they are working,” “Bonuses are the key motivation factor,” and so on.

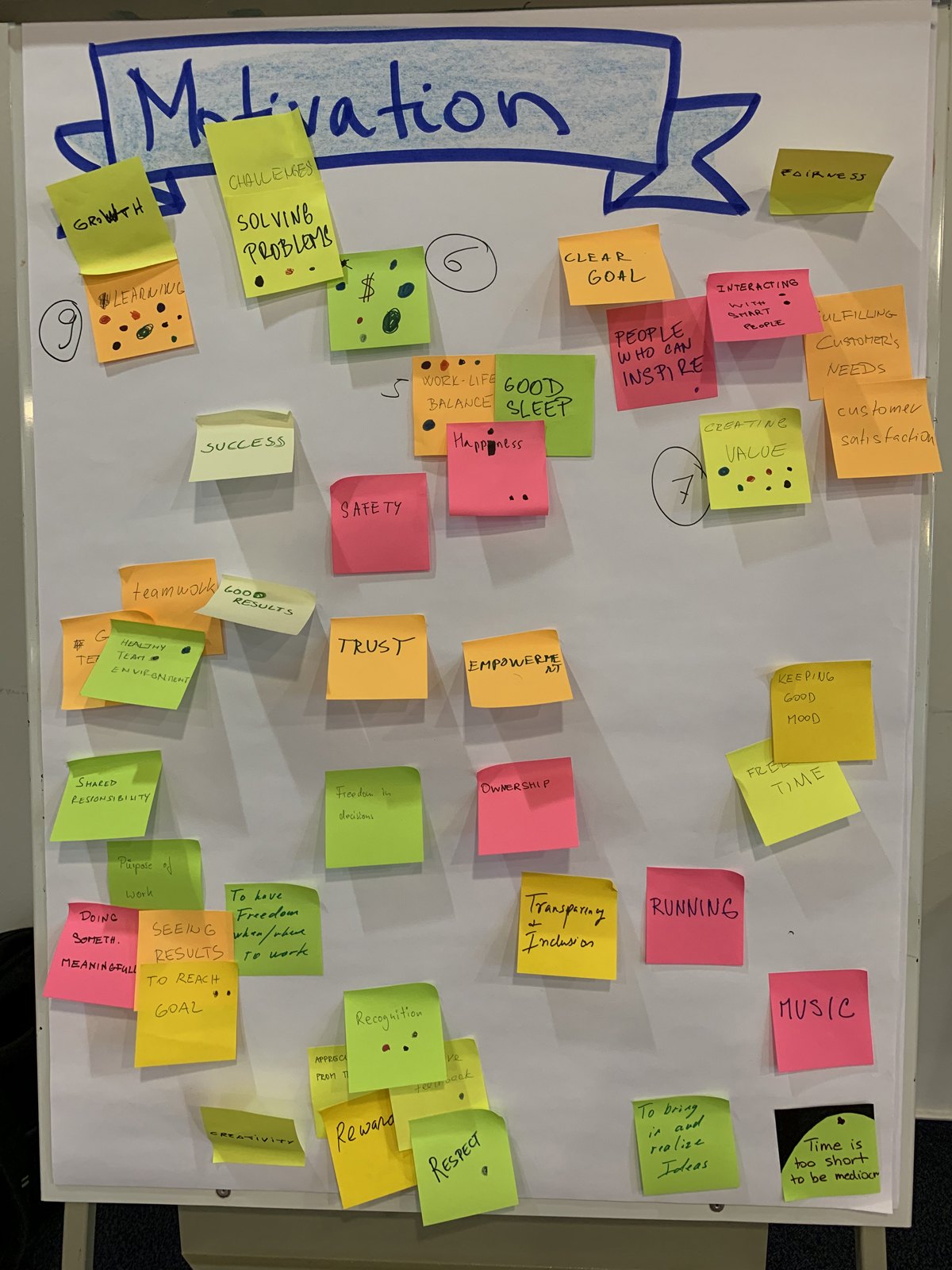

Example of the motivation factors brainstorming and evaluation

The other part of motivation is related to the environment and culture. Agile leaders favor intrinsic motivation factors, as they are more aligned with the team spirit that agile culture is built around. In the environment, people are motivated by a safe-to-fail culture, where failure is taken as an opportunity to learn and improve things, not to blame or punish people. They are also motivated by having the autonomy to come up with their own ideas for how to address the challenges they are facing, by working in a learning environment where they can grow and their contributions are recognized, and last but not least, by an open and transparent environment with a high level of trust. Those factors always win in organizations.

Just for the record, based on several types of research, money is not considered a motivating factor. “There is little evidence to show that money motivates us and a great deal of evidence to suggest that it actually demotivates us. Once the basic needs are covered, the psychological benefits of money are questionable” [Chamorro13]. In other words, people need to get paid “enough”—they need to feel their salary is fair and that they are valued. And here is the problem. This value is very personal, and it doesn’t necessarily correlate with the actual amount they are paid. You might be super happy about your salary until you open the newspaper and read the average salary of your position: “Look at that, this is what’s common, I need to get a raise.” And you might feel your salary is fair until you accidentally learn about your colleague’s salary: “He is five years younger, has less experience, and he doesn’t even work as much as I do. That’s not fair.” Surprisingly, if you overpay people, it creates a similar effect: “Guess how much I got for just doing my regular job. Next time I will ask for twice as much.”

In agile, we invest in building social capital. Interestingly, money erodes it. Chamorro-Premuzic reports that the results of a meta-analysis3 “highlighted consistent negative effects of incentives—from marshmallows to dollars—on intrinsic motivation” [Chamorro13]. On one side, we are trying our best to create an engaging environment that would motivate people by intrinsic factors of motivation, and on the other side, we are destroying or lowering the effect by extrinsic factors of motivation (i.e., incentives). That’s quite a disconnect.

As in many organizations, ours has some motivated and engaged groups and some very demotivated ones. One of the most difficult cases we needed to solve was a team that was traveling to the customer site every week. It was a long drive, they stayed in a hotel they didn’t like, and from a technical standpoint the work was boring. They were getting extra money to compensate for the extra effort, but that money didn’t bring the expected motivation, and one day the entire team almost left the company. At the end of the day, they stayed, except for their team lead. We couldn’t change the technical part of the work, and we actually couldn’t give them more money either. However, what we did was to carefully listen, for the first time ever, to what they were complaining about. We were also fully transparent about the finances and gave them significantly higher autonomy to decide where they spent the budget and on what basis they were rotating to travel. As a result, they changed the hotel and the cars, as well as the system of who was traveling and who was staying at our offices. It was interesting that a small change can make a huge impact. In a couple of months, this was the product everyone was proud of working on, and people were asking to be assigned to that team.

Theory X and Theory Y

One of the most famous theories about motivation, described by Douglas McGregor in 1960, is called theory X and theory Y [McGregor60]. Theory X defines people as lazy slackers who dislike working, avoid responsibility, need to be directed and controlled, and whose actions need to be traced. You often need to threaten them in order for them to deliver any work at all, and, on the opposite side, their direct reward must be linked to the outcomes. This is where classical micromanagement comes from. All the detailed timesheets, task assignments, and performance reviews are grounded in the theory X beliefs.

In contrast, theory Y defines people as enthusiasts who consider work as a natural part of their life, are motivated, always take ownership and responsibility, enjoy working in the company, don’t need many directions, are self-directed and self-controlled. That’s where agile was born, based on self-organization, autonomy, and empowerment.

Keep in mind that nothing is black and white. Companies will use a mixture of techniques based on which theory is closer to their beliefs.

Try the following assessment. Make a mark somewhere on the scale from X to Y.

Here is the interesting paradox. I’ve run this experiment many times in my classes, and 95 percent of people who do this exercise would rate themselves to be more Y than their colleagues. Once I question them, they find different excuses for why that is (e.g., “I’m the manager, so I’m better than the others, that’s why I’ve got promoted”; “That’s why I’m here, learning about agile leadership”; or “That’s because we care about agile and they don’t”). In other words, about half the people believe that they are better than others. They don’t need the carrot and stick in order to work, but they don’t have that trust and confidence in their colleagues, so they feel others need that control.

Niels Pflaeging has been running this experiment at conferences for years.4 And it’s pretty eye-opening. Imagine the whole conference room, about a thousand people, answering the first question: “What kind of person are you? Write X or Y on a pink Post-it Note, and exchange it with your neighbor.” No one believes himself or herself to be an X theory person. Pflaeging then asks them to answer the second question: “Think about all the people in your organization—what percentage of theory X people are there? Write it on a yellow Post-it and exchange it with your neighbor.” Now here comes the interesting point: the vast majority of people believe that theory X people exist, and that’s very dangerous. As Pflaeging said, this belief that other people can be theory X is a self-fulfilling prophecy, a terrible prejudice and judgment. We are responsible for creating the environment that generates theory X behavior, not theory X people; we do it through the way we work and through the tools we use [Pflaeging14].

Along with McGregor and Pflaeging, I believe that theory X people don’t exist, have never existed, and that there is not a single theory X person in the world [Pflaeging18]. It’s only our having treated people that way for ages that has created this kind of behavior. All those timesheets, performance reviews, estimates, roadmaps, and velocity charts—they show our lack of trust in people, trust that they will do their best even without pressure and control mechanisms. Trust. It’s so simple to say it and so hard to build it. At the end of the day, that’s what agile leadership is about. Trust that there are no X theory people in this world, and if there is X theory behavior, it’s our role to work on it and change the environment, culture, and tools we use so it disappears.

What practices that stimulate theory X behavior do you have at your organization?

What practices that stimulate theory Y behavior do you have at your organization?

What can you do to improve the ratio between the practices that stimulate theory X and those that stimulate theory Y behavior?

Engagement

Engagement is a very important part of motivation. The ADP Research Institute’s Global Study of Engagement is pretty pessimistic: “Only 15.9 percent of employees worldwide are Fully Engaged. . . . This means that almost 84 percent of workers are merely Coming to Work, and are not contributing all they could to their organizations” [Hayes19]. Considering the study reports on almost twenty thousand workers in different industries and countries, it is concerning. What is also interesting in this report is the finding that “workers who say they are on a team are 2.3 times more likely to be fully engaged than those who are not” [Hayes19]. We can say that “when organizations make great teams their primary focus, we expect to see more significant rises in global engagement” [Hayes19].

Focusing on teams over individuals is one way agile leaders increase the engagement in the organization. The first step is always raising awareness. If you are interested in your team’s engagement, you can give them the following assessment. The assessment statements are from ADP’s Global Study of Engagement, where “the eight items are designed to measure specific aspects of employee Engagement that organizations and team leaders can influence” [Hayes19]. However, before you do that, think about your own answers and what could help you to be more engaged. It’s always good inspiration.

On a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 means “not at all” and 10 means “completely,” mark your agreement with the following statements:5

I am really enthusiastic about the mission of the company.

At work, I clearly understand what is expected of me.

In my team, I am surrounded by people who share my values.

I have the chance to use my strengths every day at work.

My teammates have my back.

I know I will be recognized for excellent work.

I have great confidence in my company’s future.

In my work, I am always challenged to grow.

You can call yourself “fully engaged” if your answer is at least 7 for each of these questions.

Full engagement is an important part of the leadership journey. If in the previous exercise you didn’t end up at “fully engaged,” don’t worry. It doesn’t mean you are disengaged or demotivated—you are just not working at your highest potential as a leader, and you might have some opportunities to improve your leadership skills in this area. For your score, you can always blame others for not creating a good environment for you to flourish in. For your teams, it’s all in your hands. You can make it happen and help your teams to feel the power of being fully engaged. “Workers are twelve times more likely to be fully engaged if they trust the team leader” [Hayes19]. The initial engagement feedback from your teams might be frustrating and harsh, but at least you know what they are missing and can work on it. The good news is that leaders can make a big difference in engagement levels by creating the right environment and building mutual trust.

Super-chickens

Margaret Heffernan presented an awesome talk at TEDWomen 2015 about motivation. At the beginning of her talk, she refers to the research done by William Muir from Purdue University about the productivity of chickens. “Chickens live in groups, so first of all, he selected just an average flock, and he let it alone for six generations. But then he created a second group of the individually most productive chickens, you could call them super-chickens, and he put them together in a super-flock, and each generation, he selected only the most productive for breeding” [Heffernan15] Isn’t that what we do with each evaluation review and each layoff? It makes sense, right? Those people with low productivity only demotivate others and lower the quality, decreasing the overall productivity of the entire group. That’s what most organizations would say, right? So, let’s have a look at the results of the research: “After six generations had passed, he found that the first group, the average group, was doing just fine. They were all plump and fully feathered and egg production had increased dramatically. When you look to the second group, all but three were dead. They’d pecked the rest to death. The individually productive chickens had only achieved their success by suppressing the productivity of the rest” [Heffernan15].

That shouldn’t be so surprising for anyone who has ever experienced being part of a great team. Great teams are not successful because they consist of super-chickens, though both the individuals’ skills and diversity are important; the most important factor that drives their success is social connectedness. Agile organizations have found that out, so they support relationships, team spirit, and various communities that connect teams across the organization. They design their offices so that people can collaborate. They have the magic walls all around, which people can use as a whiteboard. They have movable furniture so teams can create space in a flexible way, depending on the needs of the team, and can change it when the team grows. They invest in many different informal chat areas that are colorful, comfortable, and enjoyable—unlike the traditional cold meeting rooms with U-shaped tables.

Agile organizations don’t see the coffee machine as an expense but as an investment in social connectedness. They often invest in much more than coffee, and employees either have substantial discounts in their cafeteria or eat there completely for free. They create space for games where people can meet and play together and relax. It doesn’t stop with one foosball table in the kitchen area. They realize that investing in people’s relationships brings them quite significant value not only in motivation, engagement, and ownership but also in creativity, innovation, and, last but not least, performance.

Quite different from the traditional carrot-and-stick approach, right? Don’t get me wrong, all those practices such as employee of the month, the career path hierarchy, and performance reviews were implemented in organizations in good faith. However, they are coming from the false belief that only highly specialized, skillful, and high-performing individuals can make the organizations successful. Companies have been investing in super-chicken employees hoping for a super-flock to appear for the past fifty years, and it’s time to change that approach. Instead, practices such as having self-organized, cross-functional teams and investing in their collaboration and social skills seem to be much more successful.

Which practices are you using?

For your result, count −1 point for each checked box from the left column and +1 point for each checked box from the right column. The result will give you a feeling of how agile you are considering practices. The negative score is undermining agile culture and mindset, the positive one is supporting it.

Which practices would you like to try? Which would you like to avoid?

Relax area at Avast Prague

Movable space for conversation at Avast Prague

Feedback

The third segment in the top section of the Agile Leader Competencies Map is feedback. For any agile team, feedback is crucial: it’s part of their DNA and an integral part of the culture, as it gives the team an opportunity to inspect and adapt their way of working and continuously be looking for possibilities for improvement. The same applies for agile leaders, for whom the regular feedback flow is an important prerequisite for improving their leadership style. Giving feedback is only one part of the feedback flow, but receiving it is even more important. So how many times have you changed your way of working based on feedback from your peers? And how many times did you reject it in your mind, thinking, They don’t see the whole picture, it’s not relevant? Indeed, you don’t have to agree with everything people say, but if there is even just 2 percent of truth in the feedback, what does it mean to you? How can that part be useful? If you think about any feedback from the system perspective, where “everyone is right, but only partially,” your ability to learn from feedback increases significantly.

In general, when it comes to feedback, there is never enough of it. The more frequently you exchange it, the less nervous you and others feel about it. Agile leaders make feedback a routine, so it becomes a habit and they don’t even notice it. If you ask for feedback only once per year, it’s a big thing. It becomes something out of the ordinary, and that’s stressful. Thoughts such as What if they are not happy with me? and What if they don’t see the value of my work at all? occupy people’s minds and promote defensiveness and blaming as a response.

Trust, transparency, openness, and regularity create good feedback.

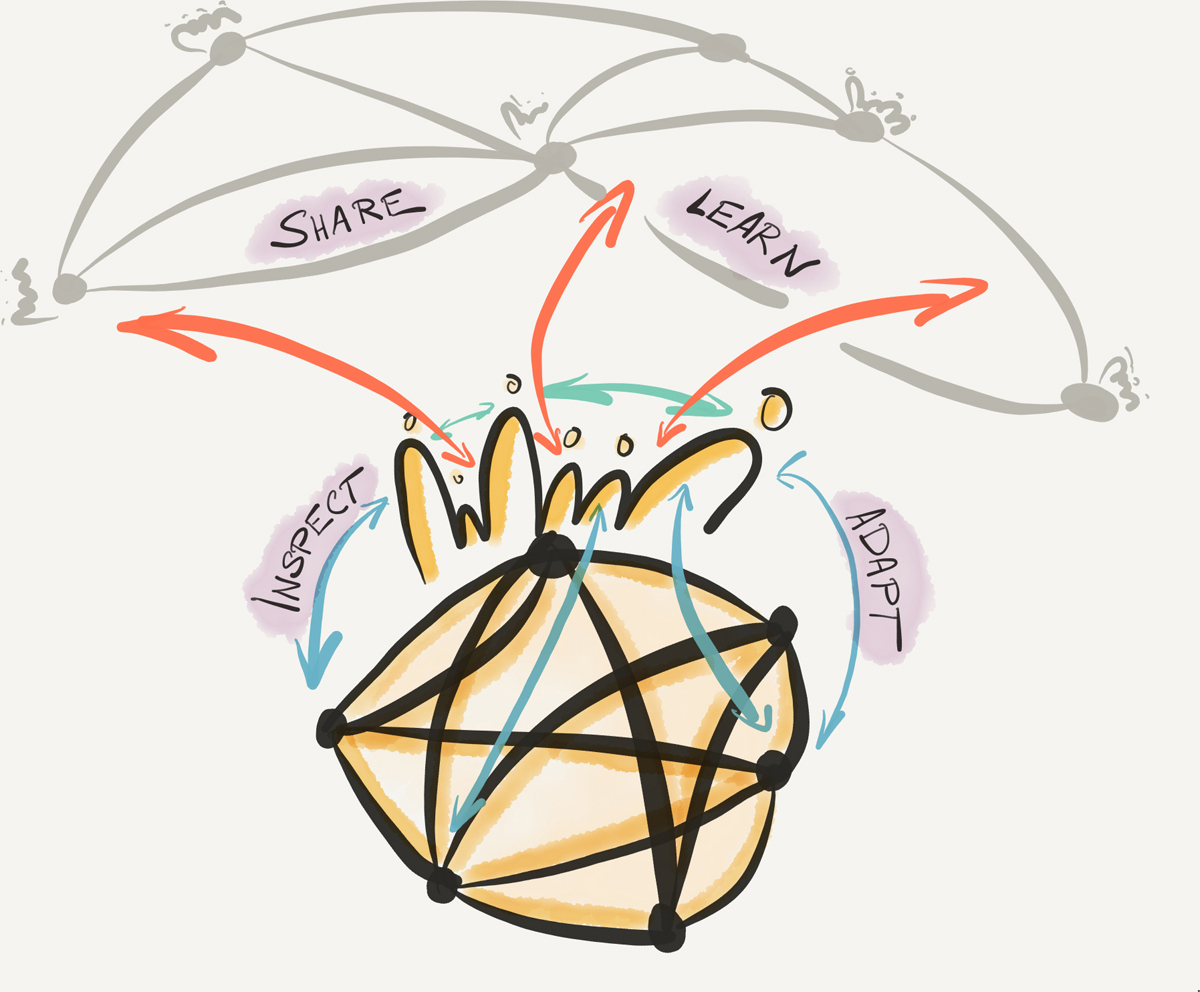

As an example, the Retrospective in Scrum6 creates a regular habit of giving and receiving team feedback in an actionable form so often that people take it as an integral part of their lives. Similarly, the Overall Retrospective,7 as it is designed in LeSS [LeSS19a], creates a habit of regular feedback exchanges at the larger organizational scale, and there is no limit to where you can use the concept of the retrospective. Feedback doesn’t stop at the individual, team, or organization level. The great agile organizations are searching for feedback from the outside world, opening up by sharing their way of working for inspiration through blogging, by inviting others to see what they do, and also by looking for how to learn from other organizations.

Opening up for feedback is a long journey. In our case, it started with small steps. First, we opened up for honest and candid feedback internally, inside of small teams, by running regular retrospectives and making them private to increase the feeling of safety. It took time. Once the trust at the team level was established and people got used to it, they relied less on retrospectives and were able to give each other feedback on the spot. They were collaborating more and becoming great teams, and feedback become part of their everyday work. The teams were strong and internal facing. However, anything coming from the outside was taken as a potential threat.

At a certain point, the teams started to feel comfortable with cross-team sharing and learning from each other. They started to feel comfortable opening up and hearing the feedback from the other teams as well. That was when we started the communities8 and discussed cross-organizational issues there. The point wasn’t to assign blame and focus on who did what, but to learn together and prevent those issues from happening again. That’s when we became more of a network than individual teams. Our interconnectedness became stronger, and we aligned as an organization.

Finally, when we became strong internally as an organization, open to speaking up and giving each other feedback as we went, we were ready to share our way of working with the outside world. We started inviting other people to see our way of working and give us feedback, speaking about it at conferences, organizing workshops for students in order to attract them, inviting candidates who were deciding if they wanted to work for us or to join us for a day to see who we were. Not only were we sharing, but we were also curious what other people saw, what they found interesting, important, and difficult. We opened up to receiving feedback because there is always a better way of doing things. It was hard at the beginning not to reject their perspective by saying they didn’t get it. But at the end of the day, once we embraced the fact that everyone is right but only partially, we were able to improve in much more effective ways.

Think about feedback in your team within the last few months.

How many times have I given my peers honest and open feedback that they could learn from?

A. Never

B. Rarely

C. Sometimes

D. Often

E. Regularly

How many times have I learned and changed the way I do things based on the feedback from my peers or employees?

A. Never

B. Rarely

C. Sometimes

D. Often

E. Regularly

What can you change so that you give and get actionable feedback more often?

Giving Feedback

Sometimes, when your culture is not quite where you’d like it to be yet and a lot of toxic behavior exists, you might still need feedback, but the environment makes it hard to give and receive it. If people have little trust in each other, you need to be more careful about what you say and how you say it. In such environments, the COIN conversation model is a good way to get the message across. Similar to other coaching tools, such as the GROW model, it guides you through the conversation and raises awareness. COIN stands for context/connection, observation, impact, and next.

Context/Connect: We start with context to connect with a specific time, event, or situation that happened in the past. When did it happen? What was the situation? What were the circumstances? Be positive, expect that everything was done with a good intention.

Observation: The observation must be specific but neutral. Don’t take sides. Just describe what happened. Don’t evaluate, as evaluation in such situations usually comes across as blaming. Observation requires you to be able to keep a distance and apply the agile leadership model. There are no right or wrong situations, just different angles and viewpoints.

Impact: The impact is very personal. It’s about your feelings, not about what is or isn’t right. How do you feel about it? What does it look like to you? What impact did it have on the team, department, and organization?

Next: Finally, the next step brings us back to the action. Help people to see there was, and is, another way to react. What could have been done instead? How can they handle it next time? Make your requests clear. What do you want them to change?

Imagine a situation where one of your colleagues, the most experienced person, was constantly sending text messages during a workshop and not collaborating with the team. The other team members say, in private after the meeting, that they felt discouraged, as they were afraid that he disagreed.

Context

“I know that you care about this product a lot, and you spend a lot of time helping this team to make it great.”

Observation

“I noticed yesterday in the workshop that you were on your phone quite often and didn’t engage much with the group. It felt like you were not engaged and were mentally out of the meeting.”

Impact

“The impact to the team was that they felt discouraged. They were afraid that you disliked what they are doing and just not saying that openly to them.”

Next

“I understand that things can happen, and I would request that you to step away if you need to solve other things and be open about it with the team. It will send a signal that you trust them with their work, and they would feel supported.”

Think about a recent situation for which you’d like to give feedback and phrase it in the COIN way to practice:

Learn from Feedback

The ability to learn from feedback is crucial on the leadership journey. Though there are many ways to reflect on the feedback, the Leadership Circle Profile [Lead19] is a great 360° profile focused on individual leader development. It compares your results with the norm base of 100,000+ leaders worldwide. It’s usually eye-opening, as we tend to see ourselves differently than others see us.

The Leadership Circle Profile combines the four dimensions of the leader personality: it compares their creative competencies (which are highly correlated with the leader’s effectiveness) with their reactive tendencies (which get more short-term results) and their people and relationship orientation versus task orientation. Knowing yourself well and getting holistic feedback as input for improving your leadership style are important steps in your agile leader journey.

When I did my assessment, I was hoping to be more on the creative side than on the reactive side. Looking at the results, creativity was definitely strong, even stronger than I had expected. However, there were some surprising segments in the reactive hemisphere, which told me things about myself I was not ready to hear, so I started making excuses for the assessment results—but the reality was different. On the reactive hemisphere, I hadn’t thought I would score high at controlling and protecting either. In retrospect, I can clearly see those aspects of my behavior, and while I believe I have improved, these traits are still stronger than I would wish for. I’ve made a big step forward because of my coaches, who, without judging me, helped me to see and accept those tendencies in myself. Get awareness, embrace it, and act upon it. I’m far from being done with it, but I’ve made huge progress on my leadership journey, and I’m glad I didn’t give up when I heard that feedback.

Despite the challenges of the VUCA world, most leaders still lead reactively [Anderson15a]. Research shows that leaders who operate from the reactive mindset are able to achieve results only to some extent, and from a certain stage forward, they are unable to generate high performance. “Reactive leaders typically emphasize caution over creating results, self-protection over productive engagement, and aggression over building alignment” [Duncan19]. In contrast, leaders who develop a creative mindset are open to new potential.

To understand a bit more about reactive leaders, let’s look at the three types of leaders and their natural tendencies [Anderson15a]:

• Heart types are people who form relationships around themselves and are satisfied if people like them and accept them. They care about relationships, and when they are afraid people might reject them, they avoid conflicts and become quite passive. When they are on their reactive side, they are seen as compliant. Their relationship focus makes them aligned with agile principles.

• Will types are trying to win by any means necessary. They are competitive, they want to have results and accomplish what needs to be done. They are anything but compliant. They care about being in charge, getting promoted, controlling things. They neither delegate nor collaborate. They hate failure, as they are afraid it will make them look weak. No matter what, they need to be the best. They are perfectionists, often micromanagers. When they are on their reactive side, they are seen as controlling, and it’s super hard for them to embrace the agile way of working.

• Head types are smart and analytical. They are rational thinkers, able to keep distance even in conflicting, complex situations. Their inner motivation comes from others seeing them as knowledgeable, as brilliant thinkers with great ideas. They are seen as cold, distant, overanalytical, and critical. When they are on their reactive side, they are seen as protective. When they are in an agile environment, they often tend to overanalyze.

Creative competencies open new opportunities. They multiply the impact you would create through leading just from the reactive mindset. “Transitioning to the Creative Self is the major transition of life and leadership” [Anderson15b]. Leaders with a creative mindset often start with a vision and purpose that generate passion and faith, which in turn translate into a clear picture that helps teams to skyrocket their success. “Creative leadership is about creating a team and organization that we believe in, creating outcomes that matter most, and enhancing our capacity to create a desired future” [WPAH16]. Creative leadership is key for fostering collaborative, agile organizations and cultures.

Creative leadership is key to agile cultures.

Leadership Growth as a Core Element to Agility

Kay Harper, Leadership and Relationship System Coach

The complexity and pace of change in the twenty-first century are creating a widening gap for all leaders in terms of their effectiveness. Data show that as the world is now more interconnected and the business environment is more volatile and complex, the definition of effective leadership is changing. Data also exist showing that leadership effectiveness is directly correlated to business performance. As a coach, I work with people to help them understand their current leadership competency, how the experiences they’ve had influence their approach to leadership, to gain awareness of their impact as a leader. When leaders have awareness, they can make conscious choices about how they are impacting their organization’s bottom line.

I remember working with a leadership team in a division of a larger company. The leadership team wanted to understand how to work with their teams and team members to help them take on more decision-making responsibility so that they could deliver value more quickly. Knowing that the leadership style of senior leaders is what creates (or prohibits) an environment in which decentralized decision making is possible, we started working with this senior leadership team. Through the combination of Leadership Circle Profile and associated coaching, the leaders each received data that provided insights into how they show up when working with teams, peers, stakeholders, and the executive team of the broader organization. The leaders each gained a better understanding of their strengths, creative competencies, reactive tendencies, and areas they could improve to directly impact their effectiveness. They each created their own action plan, and coaching was provided one-on-one and at the leadership team level. The leaders began to hold each other accountable for making the shifts to which they’d committed. Through time (and team coaching), the delivery teams learned that they had the leaders’ support as they took on more decision making. Silos broke down as more collaboration occurred within and across teams. Positivity increased when team members felt more autonomy in delivery. Eventually, the company saw an increase in both the rate of delivery and employee satisfaction. As someone who partners with organizations to help them on their path to agility, I have a hope that more leaders at all levels of organizations will see the need to lead differently and take action to further deepen these new capacities.

Decision

Even in an agile environment, you need to make a decision from time to time. Agile is not about voting or about never-ending conversations. It’s always a tradeoff: let people collaborate and figure it out, or decide yourself.

The ability to make a decision empowers. It brings energy and motivates. In traditional Organizations 1.0, the boss is there to decide. In knowledge Organizations 2.0, the manager is expected to delegate, while at agile Organizations 3.0, the leader empowers others to step in and take over the responsibility for day-to-day decisions and rely on influence over power.

As always, it’s good to know where you stand. Do you have enough trust in the system to delegate? Can you imagine letting it go? Those are just a few questions you can ask yourself to start thinking of where you are regarding the decision-making process.

Think about your organization. On a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 means “not at all” and 10 means “completely,” rate the following statements [Bockelbrink17]:

We approach challenges by experiments.

We are continuously looking for improvements.

We make all information transparent and accessible to everyone.

We focus on achieving the goal.

We always speak up when we disagree with the decision or action.

We are inclusive and always involve people who are affected by the decision.

We take over ownership and responsibility when needed.

The more on the right side you are, the more effective the decision-making process is going to be when you let it go and empower teams to make the decisions.

What can you improve in the environment to make your decision-making process more effective?

Sociocracy

Traditional organizations run a decision followed by a compliance process, while in an agile space, the decision needs to be created in a collaborative way. It’s relatively easy to imagine a small team making decisions, but would it work at a large scale? Sociocracy 3.0 brings a framework allowing you to start with alignment via double-linking, which leads to consent [Esser_nd]. In a nutshell, we speak about a fully cross-functional team that always contains the so-called double-linking—team members as well as management representatives—in order to be able to create a high-level alignment, not just local optimization. This Sociocratic Circle Organization Method was created by Gerard Endenburg9 in 1980 and developed through the years to a whole framework often used in agile space: Sociocracy 3.0,10 which defines seven principles and a series of patterns [Bockelbrink17] on how the organization can operate and make decisions leading to the autonomous, tolerant execution.

The principles of empiricism, continuous improvement, and high transparency are not anything new for the typical agile environment. The effectiveness principle, which says you shall “devote time only to what brings you closer toward achieving your objectives” [Bockelbrink17], can be reframed as another agile value: focus. Finally, the remaining three principles are specifically important in the context of decision making:

• Consent creates openness around any objections and disagreements.

• Equivalence promotes inclusivity and involves all people affected by the decision in the decision-making process.

• Accountability brings the ownership and responsibility to act when needed.

A collaborative approach to agreements, together with the high transparency and continuous evaluation from Sociocracy 3.0, results in solid decisions and makes the organization very flexible when reacting to issues.

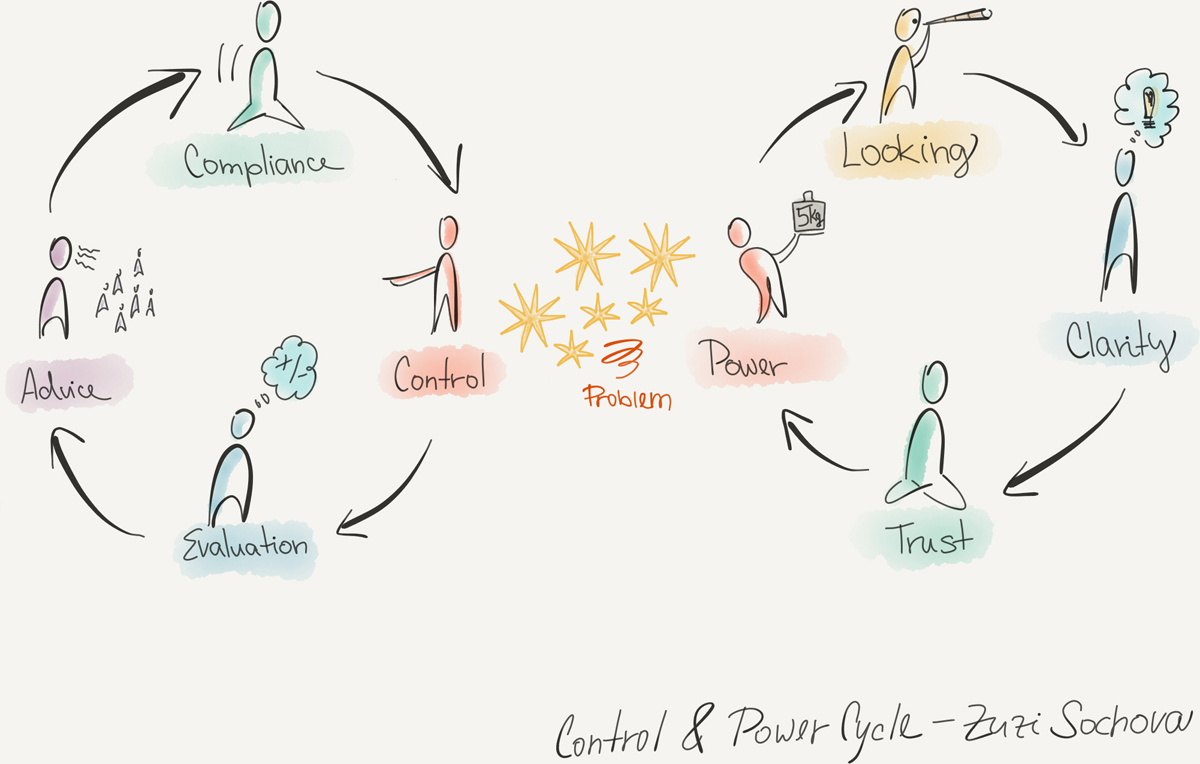

Power and Control Cycles

Now let’s take a closer look at what is happening in your brain when you are facing a problem and what kind of reactions you have. Christopher Avery describes it in his program The Leadership Gift11 and in more detail in his book [Avery16]. The concept goes deep into your mind, uncovering your internal processes, feelings, and reactions. Why do you often react a certain way? As Avery says, “The scary part is the need to give up control to increase power and freedom” [Partner17]. It all starts with fear. Fear of failure. Fear of losing control.

When you face a problematic situation, your brain guides you either through the Power Cycle or the Control Cycle. The Control Cycle is a reflection of the fear of losing control—it’s grounded in traditional management, where control is all that matters; otherwise you might look weak and unimportant and won’t be promoted or won’t deserve your job. Whenever a problem emerges, fear starts to take over and you try to get your control back. You evaluate the situation, weighing thoroughly all pluses and minuses, and look for advice on how to solve it by creating yet another rule that would prevent such things from happening or for any process that can help you to regain control. And the mental trap is in motion. With every evaluation followed by advice, you make a decision on what is right and what is not, and then expect compliance. When that’s not happening, you feel an even greater fear of losing control, and that fear is strengthened by the feeling of betrayal. You evaluate the new situation, decide whether or not this should happen, search for ways to regain control, and so on. The fear of losing control grows and generates wider and stronger frustration, which puts increasing pressure on the environment.

Alternatively, you can choose to follow the Power Cycle. It’s not hard, but you must break your current habits and react in a different way than what you are used to. When a problem emerges, instead of evaluating it, you start looking for reasons why it is happening, finding the root cause, trying to see it from a system perspective. The process of looking for reasons brings more clarity to the issue. It shows you different perspectives, makes you curious. Clarity brings quietness and relief to your mind, which eventually creates trust in yourself and in others, which closes the circle and brings you more power than you felt before. “The Power Cycle is not an easy choice at first; however, it is a self-reinforcing dynamic that we can rapidly learn to trust” [Partner10].

To get into the Power Cycle, the first step is to recognize which path you are used to taking. Once you have enough awareness to recognize the pattern before you react in the usual way, you can intentionally choose to look for understanding, take a system view, and apply the agile leadership model instead of going to the evaluation and searching for what is right and what is wrong. Like every change, it takes time, but it is worth it.

Collaboration

Agile is all about teams and collaboration. Individuals are not that important. There is nothing magical in this concept—it’s just that people got so used to working as individuals that they forgot what collaboration is about. However, collaboration is the key aspect of the agile environment, and if you can’t collaborate, there is no way you can become an agile leader.

The traditional organizations are all about processes, rules, and delegation. All we need to do is analyze the situation, decide how we want to handle it, describe it in a process, and follow that process. It shall be enough. It’s a world where we rely on processes in our day-to-day decision making. “The process will solve it,” people say. In simple situations, it works well, and the transparency and predictability of the situation are an advantage. In complicated situations, this model might not be flexible enough, and people and organizations will struggle to react properly. In a complex situation when it’s hard to predict what will happen, this method usually fails.

Tight processes are killing creativity and work only in simple and predictable situations.

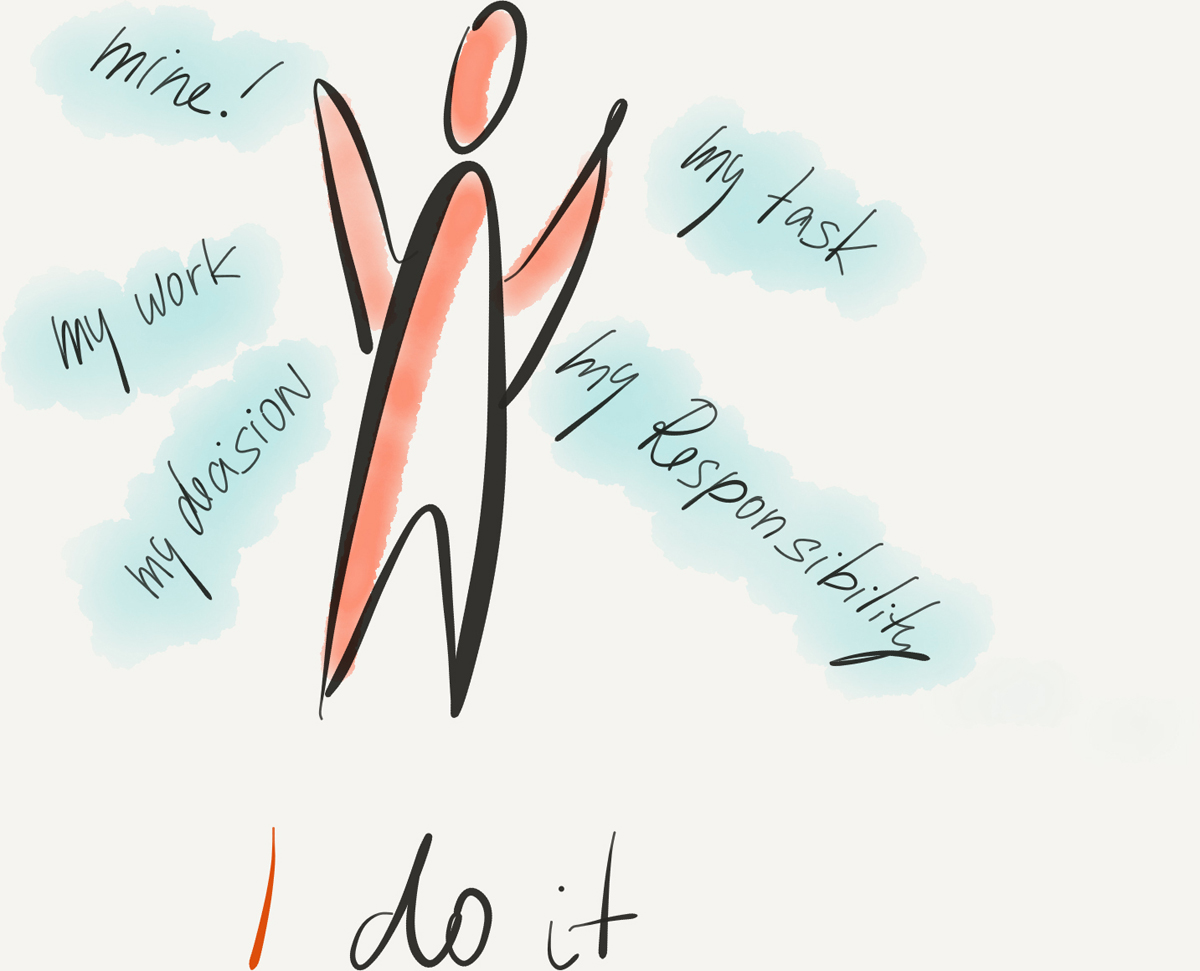

The more complicated the situation a company faces on a day-to-day basis, the harder it is to describe the process to be followed. It seems to be unavoidable that rules and practices are not enough for success; delegation comes into play, and new roles and positions are created for those responsible for a certain part of the process. It’s the world of individual responsibility, where we create a single point of contact who takes care of things and whom we can blame when things go wrong. You can volunteer and say, “I’ll do it,” or you can assign it to someone else and say, “You do it.” In any case, there is no real collaboration. Such role-splitting allows more flexibility because, unlike in the process-solves-it approach, people can make a judgment based on the particular situation and solve it more effectively than if they strictly followed processes.

Individual responsibility kills collaboration and team spirit.

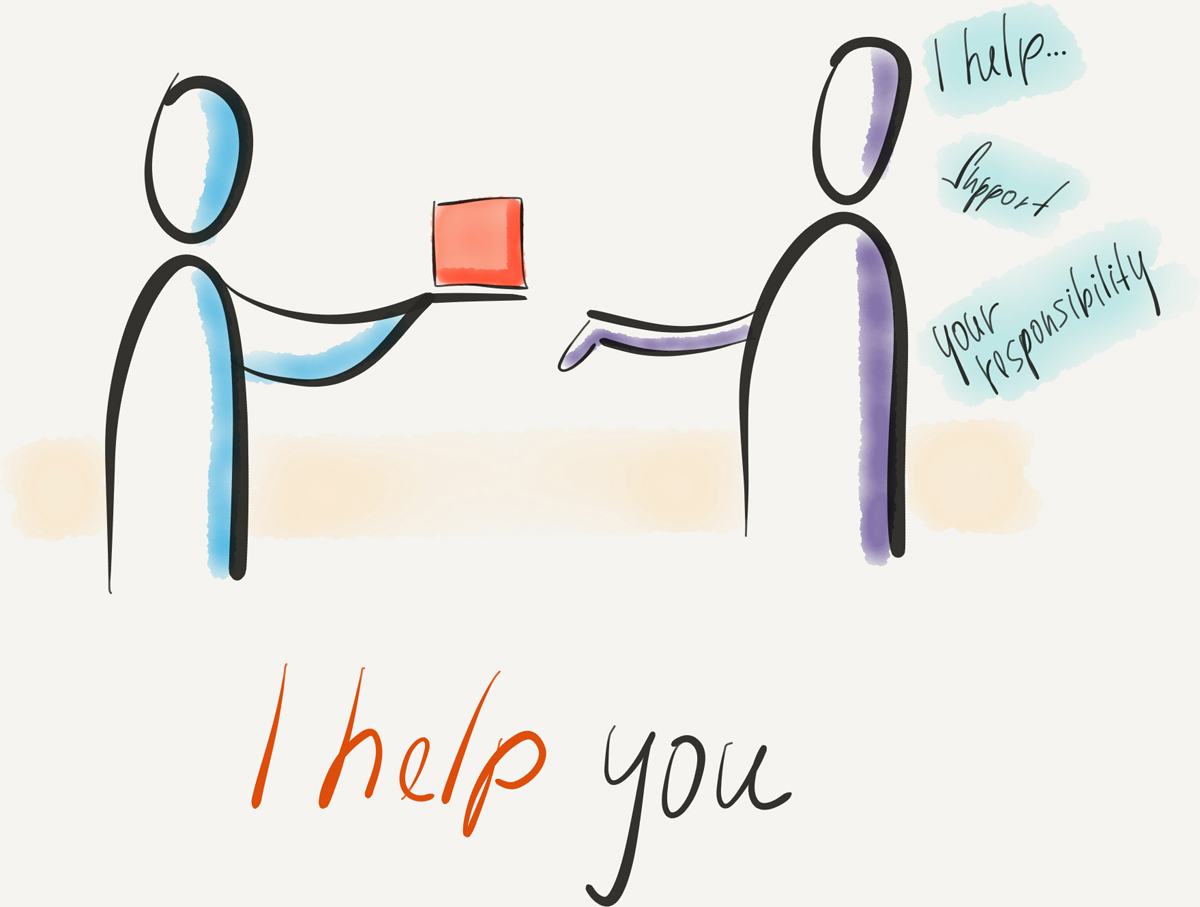

By starting to help each other, we cross the line of collaboration. People start working together, offering help to others and asking for help themselves, which starts to feel like a collaboration, at least at first glance, as more people are working together.

However, there is still one person responsible, and the other is just the helper. It’s a good first step, but at the end of the day, it’s closer to delegation than collaboration, as the unequal ownership makes one side more invested in the results than the other; the owner usually makes the plans and decisions and feels responsibility, while the other person supports the owner with the inputs. It’s still more likely to create blaming than a sense of shared ownership and responsibility. It’s a start, but it’s not collaboration as we understand it in an agile environment.

Helping one another with certain tasks is not collaboration. Collaboration requires equal ownership.

Finally, where there is real collaboration, people have shared responsibility, shared ownership, and one goal. “We do it together,” they say. It’s not important who does what, and there is no task assignment up front—they all just do what is needed and make their decisions as the need arises. This is the type of collaboration that makes teams in agile and Scrum great and creates high-performing environments. If you truly want to be agile, and not just pretend that following some practices is enough, it’s time to get rid of individual responsibility—which is often grounded in your org chart, position schemes, and career paths—and learn how to create a real collaborative environment with shared responsibility and ownership. Learn how “We can do it together.”

What can you do at your organization to enhance true collaboration?

The Importance of Pair Work

Yves Hanoulle, Creative Collaboration Agent

We all know that, in theory, two pairs of eyes see better than one. Yet when I’m facilitating an exercise in a pair and my partner interrupts me to talk about something I missed, I’m always flabbergasted. For me, feedback in the moment is the best kind of feedback. It does not make that particular training better, but it improves all my future workshops.

In 2009, I started asking the organizers of my international workshops to put me in contact with someone else who is interested in and knowledgeable on the topic. This person and I prepare the workshop remotely and run it as a pair. Most of the time, we have never physically met before the workshop. Yet we have built trust in each other. We always discuss how we will interrupt each other and other ways to send each other signals. A technique I like is to use is color-coded Post-it Notes that we post on the computer we use to present:

Green: We are ahead of schedule. You can take your time to talk a little longer, add an extra story.

Yellow: We are on schedule. Keep talking as we rehearsed.

Red: We are behind schedule. We need to speed up and drop some stories.

There is another use for pair-coaching: when I start working for a company, I’m hired for my knowledge and my experience. Yet that experience has also taught me that I can’t use my knowledge without knowing or better understanding the company that hires me. For that, I prefer to pair up with a person who knows the company. I channel my experience and in return I learn about the company.

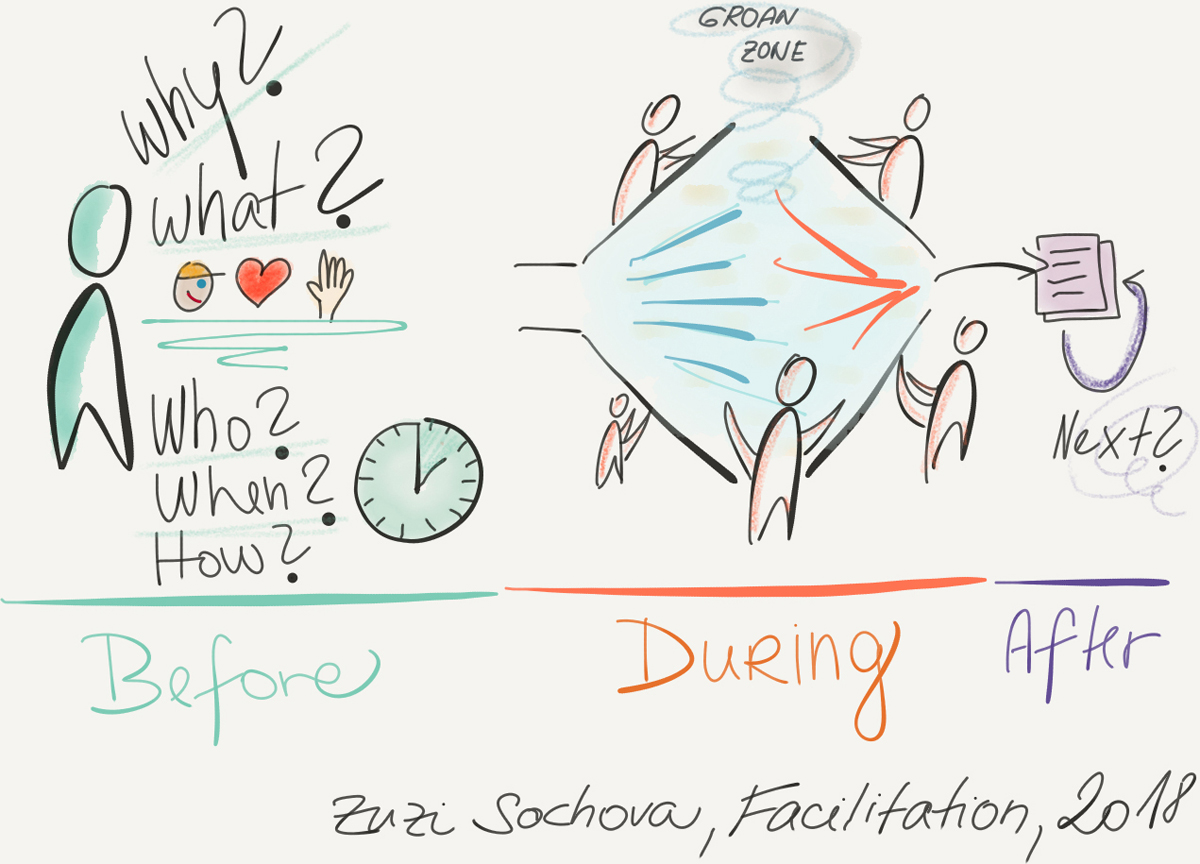

Facilitation

On the right side of the Agile Leader Competencies Map are the facilitation and coaching skills. Until team collaboration becomes the natural way you work, facilitation is a crucial skill that enables effective communication. “In the new knowledge-based, networked economy, the ability to talk and think together well is a vital source of competitive advantage and organizational effectiveness” [Isaacs99].

In the agile world, we rely on facilitation as a core competence. It’s all about the ability to talk with each other in an effective way. It’s a place where creativity and innovations emerge. The ability to read the room and understand the different communication modes is the starting point in forming collaborative structures. It starts with teams, but eventually you need to be able to scale it to the organizational level of communities and networks of teams and to create an environment where they can all collaborate together even outside of the organizational borders.

Facilitation, a Key Agile Leadership Skill

Marsha Acker, author of The Art and Science of Facilitation: How to Lead Effective Collaboration with Agile Teams

When done well, facilitation is a skill that is not very visible. I was a trained facilitator before I discovered the mindset of agility. Skillful facilitators know how to be present with what’s happening in a meeting, aware of both what’s being said and what’s not being said. In my own experience of leadership, facilitation has served me well. Early in my career, I remember feeling almost paralyzed when disagreements broke out in meetings. I would become silent, unable to find my voice. But in the silence, I realized that I could often see what others couldn’t: both sides of the argument. Yet I was afraid to say anything for fear that it would mean taking one side over the other or that it would help one person “win” the argument when I thought they both had valid points.

Deepening my practice of facilitation skills—along with building a richer understanding of group dynamics and being able to read the room—helped me shift my thinking. Rather than believing that disagreements should be avoided in order to have a productive outcome to a meeting, I began to realize that different perspectives are necessary in order to move a group forward. I learned that naming the patterns I could see in group dynamics was sometimes more important than making suggestions for new solutions. I went from facilitating meetings where I would do everything I could to avoid surfacing conflict or differing points of view to viewing them as necessary to group conversation and dialogue. I began designing ways to surface different points of view in order to create an environment where people could voice their perspectives in a constructive manner.

In The Advantage, Patrick Lencioni writes, “There is no greater way to change the culture of an organization than by changing the way it does meetings.” I’ve watched this truth play out in client organizations time and time again. We spend so many hours in meetings each week, and yet there are often lost opportunities for greater dialogue of the sort that leads toward more innovation and new thinking.

Four-Player Model

One very interesting concept describing communication is the Four-Player model created by system therapist David Kantor [Kantor12]. It’s an interesting mental map for a facilitator to see where all different actors—or players, as he calls them—stand. In every conversation, you can choose from four different approaches: Move, Follow, Oppose, and Bystand.

The move starts a conversation around a certain topic. At some point, it generates a new idea, then jumps to a different topic. Once that happens, some people follow and support what was said. Others may oppose the idea and disagree through their own argumentation. Finally, the last group of people may bystand and provide a different perspective on what is happening in the conversation. Any healthy conversation needs balanced approaches, and very often the bystand is what is missing the most in the system. It brings the high-level nonjudgmental perspective that creates new options and allows people to look at the situation through different lenses.

If there are only movers, no one listens to each other, and no real conversation occurs; people don’t search for understanding. With no one opposing, the conversation might lack depth, but when people are mostly opposing, they usually shut down the others, and the conversation lacks variety.

The Move–Oppose line is about advocacy, while the Bystand–Follow line is about inquiry [Isaacs99]. Any healthy environment needs both lines in balance; otherwise, collaboration suffers from lack of perspectives.

This example demonstrates the differences between an unbalanced and a balanced conversation around deciding where to go for lunch.

MOVE ONLY

John: Let’s go to Taco Taco. They have great food there. (Move)

Maria: I would like to go to Fresh for a salad. (Move)

Fred: It’s Friday, so we should go to the Four Stars Pizza at the corner. (Move)

Jenny: The Tri-Tri has great sandwiches, and it’s nearby. (Move)

The speakers are not even close to agreement. They each are pushing their favorite solution, and it seems they are not even listening to one another.

ADVOCACY LINE TOO STRONG

John: Let’s go to Taco Taco. They have great food there. (Move)

Maria: Mexican food is not healthy. (Oppose)

Fred: It’s too far away, and it always takes too long to get service. (Oppose)

John: Taking a short walk there is healthy, and we can order online before we go to make it faster. (Move)

Jenny: It is too far, and I need to be back for the meeting. (Oppose)

Again, agreement is no closer. It even creates friction, as the Oppose arguments feel more like pushing. Such communication usually creates defensive behavior, which is not helpful in any conversation.

HOW THE INQUIRY HELPS

John: Let’s go to Taco Taco. They have great food there. (Move)

Maria: Mexican food is not healthy. I would prefer to go to Fresh for a salad. They have a Caribbean week right now, plus it’s nearby. (Oppose, followed by Move)

Jenny: I would definitely prefer to go somewhere nearby. I need to get back in time for a meeting. We can also try Tri-Tri. It is nearby, and they have healthy options on the menu. (Follow, Move, Follow)

Fred: It seems we are looking for somewhere with tasty food, within walking distance, and with some healthy options. Any other ideas where we can go? (Bystand)

Such a conversation already feels quite healthy. People not only are listening to each other but also are aware of the overall situation.

Talking about lunch is a very simple conversation example in a small-team context. You might ask why we even need a model to agree on lunch. However, the same conversation patterns are happening at a large scale at the organizational level, and you need to be aware of them so you can re-create the balance.

When communicating, everyone has preferred modes where they feel comfortable. What is your most common communication mode?

• Move

• Follow

• Oppose

• Bystand

From a supporting skills perspective, a facilitator needs to practice voicing, listening, respecting, and suspending. “Four practices can enhance the quality of conversation: speaking your true voice and encouraging others to do the same; listening as a participant; respecting the coherence of others’ views; and suspending your certainties” [Isaacs99]. To refer back to the agile leadership model, listening helps you to get awareness. By hearing all the voices in the system and seeking all the perspectives, you bring diversity and more color to the conversation, while the suspending practice helps you to embrace it and let it go. Act upon is happening on the advocacy line between the move and oppose, using voicing and respecting. Voicing is the most courageous and hardest to achieve as you need to express your own feelings and show them in a broader context. “When we move by speaking our authentic voice, we set up a new order of things, open new possibilities, and create” [Isaacs99]. When used well, voicing has the potential to bring the conversation to a new horizon, to create a new quality of dialog. Finally, respecting is the practice that brings trust. It encourages others to engage in the conversation and actively participate. Everyone is right, but only partially.

As a servant leader, you need not only to practice those skills yourself but to help others become great at voicing, listening, respecting, and suspending as well. The more you invest in that, the better and more effective conversations they will have, and the more likely they are to be successful at collaborating and being a great team.

Which skill is your strength?

• Voicing

• Listening

• Respecting

• Suspending

Which skill (voicing, listening, respecting, suspending) do you most need to improve? What can you do about it?

Coaching

Coaching is another soft skill that agile leaders critically need for their success. The International Coaching Federation12 defines coaching as “partnering with clients in a thought-provoking and creative process that inspires them to maximize their personal and professional potential” [ICF20], which is a very different skill than most people are used to applying in an organization. It’s all about raising awareness and letting people figure out their own way instead of telling them what to do, explaining, advising, or sharing your own experience. In the context of this book, we are not speaking about one-on-one coaching. Great agile leaders use coaching to address the complexity at the system level and to coach organizations as a whole system.

Let’s think about coaching from the perspective of the leadership agility model (see Chapter 4) For the Expert leader, coaching feels like it’s from a different planet. “How can I help people if I don’t tell them what to do?” they often ask, and they end up disappointed, as coaching doesn’t solve any of their problems.

From the Achiever perspective, coaching can be useful, but only from time to time, as the results are more important, and those talks take too much time. They prefer to focus on the work and flow, and they use coaching only accidentally and in rare cases.

Finally, from the Catalyst perspective, coaching is crucial. It helps leaders to keep their relationships healthy and creates a space where people can be successful. Coaching is the key to the next level. The more you believe in people, the more you know that the people around you are smart and creative, they figure out things you might never understand, and they have brilliant ideas. Still, from time to time, they get stuck in their own worlds, seeing only one angle of the situation; they can’t take a step back to see the big picture. Their previous experience is limiting them and closing them into a certain layer. Every now and then, no matter how great they are, they don’t see the obvious. Coaching is the right tool that helps teams to search for new perspectives and raises their awareness of the system. Everyone is living in their own bubble created by context, previous experience, and the situation at hand. Coaching breaks those boundaries and allows them to step out of the bubble and extend the boundaries of the current reality.

People often ask me how they should start with coaching, so let me share what I did. I have a technical background, so learning soft skills was not natural for me. Many years back, I started as a developer, writing rather low-level software in C++. It was quite a predictable world. A few years later, I became a ScrumMaster and heard for the first time about facilitation and coaching. My reaction was simple—I rejected the idea. It just didn’t fit my world. I saw people as smart experts, so why would they need facilitation? They could handle a conversation themselves. And coaching? How could just asking questions possibly be helpful? So I rejected the idea and focused on other things.

Time went by, and the topic of facilitation and coaching kept coming up on different occasions. The change came after a talk I attended. Through the way he gave his talk, Radovan Bahbouh, a psychologist and coach, managed to change my belief that coaching didn’t make any sense. I could not get it out of my head and started talking about it with friends and colleagues. Soon after that, I went on a weekend snowboarding trip. I’d seen those other snowboarders going down the hill smoothly, without any effort, and I felt desperate. I had been trying to learn snowboarding for a few years already, and the previous year I’d even signed up for a private lesson. It didn’t improve my style at all. I was sharing this concern with my friend, and he asked if I’d like to try to get some coaching. I looked at him with a mix of surprise and disbelief. “You said earlier that you want to try it, so this is an opportunity, if you’d like to take it,” he said. Long story short, later that day, I was able to do the curves without any effort, like the other snowboarders I’d seen from the lift. And I’ve never forgotten that feeling.

When I got back, I went to a bookstore and bought a book about coaching and started practicing. Later, I joined classes from the Agile Coaching Institute13 to practice the agile coaching and facilitation basics, and then the Organizational Relationship System Coaching (ORSC)14 to deep-dive into the system coaching domain. It has been a long journey, but I can say that the most important thing that made me believe in coaching was experiencing it firsthand. When I faced an issue and everything else was failing, coaching made a difference. So if you are reluctant to put your faith in coaching, find a coach and let him or her help you with an issue.

Change

The last piece on the Agile Leader Competencies Map focuses on our ability to implement change. Change happens at three levels. First, there is a change in yourself, your beliefs, reactions, approaches, behaviors, and habits—the way you work. Through that change, you become a role model of an agile leader, and people will follow. “Use Your Self: You are your most important tool for change, using your skills of empathy, curiosity, patience and observation” [Derby19]. Every change is difficult, and personal change is usually the toughest. However, the result will definitely pay off. Leaders need to change first. The organization will follow.

Start with yourself: be a model of an agile leader.

Second, there is the ability to influence others. Make them part of the team, create an environment where they become the first supporters, and together create a snowball effect and change the organization together.

Finally, the third level of change is change at the system level. Focus on the entire organization, have the system perspective, and internalize the agile leadership model: listen to the voices of the system, get awareness of them, embrace them, and act upon them. From this viewpoint, the individuals are not important, and neither are the teams. The system level focuses on the overall harmony of the organization, the level of energy, the culture and mindset.

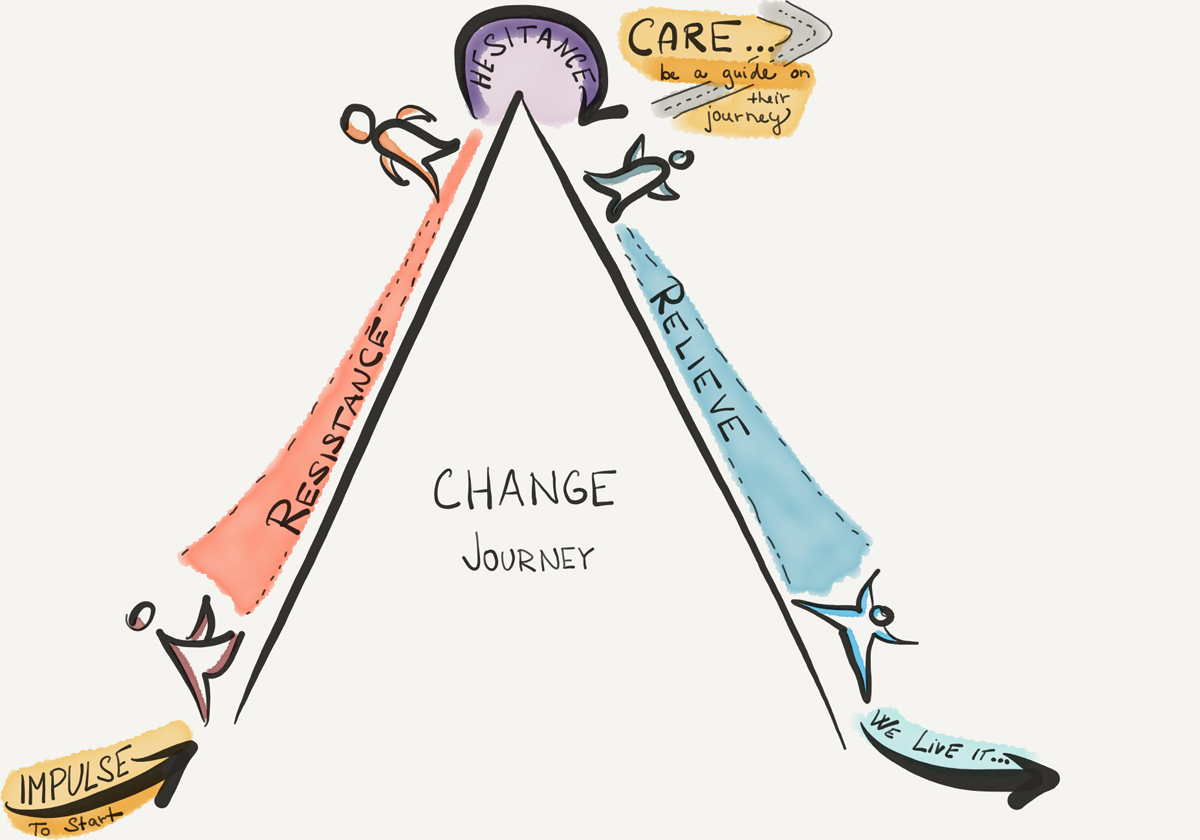

The Change Dynamic

Changing an organization is a long-term task. Most people focus on the beginning. They make an enormous effort to plan it and prepare the first steps. They give special attention to the initial impetus that would overcome resistance. They are careful to guide people in their first steps. And then, when it all starts moving, they get distracted by other tasks and refocus on other issues.

At first, everything goes well, so the change seems to have been a smart move. Give people space, let them move ahead, allow them to find their own way of overcoming the obstacles. Isn’t that what self-organization is about in the first place? But things are never that simple.

Daniel Pink, author of When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing [Pink18a], describes in examples from various research the importance of the midpoint: “Midpoints are really interesting, sometimes they fire us up, other times they drag us down and simply being aware of midpoints can help you navigate them more effectively” [Pink18b]. Being mindful of where you are in the process of change is the most important part of being an agile leader. Midpoints are hard. Psychologically, you need to make a step toward a new way of working, a new mindset. People are hesitant. At the midpoint, they no longer feel resistance, but they are lacking the passion for a new way of working as well. They are balanced in the middle and looking for assurance, support, and encouragement. They are looking for a guide to help them step over the edge, find relief, and embrace the new way of working.

Put Down Your Sword and Just Listen

By Linda Rising, co-author of Fearless Change and More Fearless Change