11. Tools and Practices

System Coaching and Facilitation

Two of the most important skills for the agile organization are system coaching and facilitation.

We don’t stop at individuals; we need to be able to coach teams and larger systems. As agile at the organization level is still very new, unfortunately, there are not many coaching programs that focus on systems. One is Organization and Relationship Systems Coaching (ORSC), which is very much aligned with agile and is widely used by agile coaches [Šochová17a]. In Chapter 6, I described three system coaching tools: the three levels of reality, High Dream/Low Dream, and Bringing Down the Vision. System coaching is also the key skill the agile leadership model (Chapter 5) is based on, so you will use these skills every day.

The more organizations rely on collaboration and forming networks, the more facilitation of large group workshops, conversations, and brainstorming becomes indispensable. Facilitation brings neutrality and helps people find alignment and mutual understanding. They own the process, while the participants own the content. “Facilitation is like a complex dance of polarities. When teams come together to collaborate, rarely are topics or decisions black and white with a clear ‘right’ answer” [Acker19]. Like system coaching, there is no right and wrong in a complex system, there are just different perspectives, and the goal of the facilitator is to make sure the voices of the system are heard without being judged.

The Value of Facilitation Skills

Marsha Acker, author of The Art and Science of Facilitation: How to Lead Effective Collaboration with Agile Teams

Agility requires leaders to think differently—to break old habits of planning and controlling for the sake of finding new ways to learn quickly and be able to adapt. The kinds of problems organizations face today require many minds thinking together about how to solve challenges and move forward.

My wish for leaders at all levels of organizations today is that they come to value and appreciate the art of facilitation skills. That they do the work to learn and become practiced at what it means to be more neutral in how they listen and participate. That they create environments where all voices are equally heard, dedicate time to hearing different points of view, and find the right balance between not rushing to a final decision too quickly and not getting stuck in the soup of opinions.

Open Space

One of the very interesting formats of facilitation at the complex system level is Open Space. The Open Space format is a facilitation technique that enables system creativity and allows a large group of people to work on a common theme in a distributed way. It uses self-organization and gives people the opportunity to choose the specific topics they wish to discuss. Sounds complicated, but it’s not that hard. It’s just a different way of having a conversation about ideas.

The Open Space format has only one simple rule and four quite philosophical principles. I remember that I was discouraged by their abstractness at the beginning. They sound very complicated when you read them for the first time, but they simply describe self-organization. The moment I stopped analyzing the principles and applied them at a higher level, I realized that Open Space is an awesome tool.

The Law of Two Feet is the key rule of Open Space.

The Law of Two Feet sets the foundation for Open Space. It allows everyone to take responsibility for what their interests are, and if they find themselves in a conversation isn’t holding their interest and to which they are not contributing, they must use their feet and go to another topic circle where the conversation is more interesting or relevant to them.

This is probably the key to Open Space’s success. Just imagine using this law at work every day. How many meetings would you stay at? The conversations you attend would be much more interesting, and let’s not forget how much more time you would have for them. The Law of Two Feet is a game changer, as it defines participation as voluntary. Everyone can participate, and they can leave when the Open Space no longer offers them relevant information or interaction.

While the law is the foundation, the four principles [Stadler19] define self-organization and help people to get the most out of participation.

Whoever come are the right people.

All those who are interested in a conversation are the right people to attend the Open Space. Participation is open to everyone. You cannot limit it by number of people, experience, or knowledge. Open Space must be open to everyone, and it sets no limitations for people to join.

Whatever happens is the only thing that could have.

Don’t think about “what would happen if. . . .” The conversation runs in the direction it runs, those who came are the ones who are here, and what is happening right now is the only thing that has to happen. In our lives, we are all influenced to a certain extent by our experiences, ideas, and plans, which constantly force us to think about the past or the future. The “whatever happens” principle brings us back to the present moment, where we stop evaluating what could happen and fully focus on what is happening right now, in the present.

Whenever it starts is the right time.

Creativity cannot be planned, and our task is to not limit the flow of creativity. Whenever it starts, it’s the right time. And if that means you need to continue the conversation longer than you planned, you continue the conversation for as long as necessary. If that means you start later, that’s fine as well.

When it’s over, it’s over.

Creativity has its own rhythm, so pay attention to it. Time is not so important. If you feel it would be a good idea to end the topic, ask the group. When they agree, finish and go to the next thing that interests you; if not, you continue with it and investigate the topic in more detail.

As you can see, there is nothing difficult about it, but it requires an agile mindset as a prerequisite. Open Space would feel really weird in the context of a traditional mindset where people believe that every conversation must have a clear leader and decision maker, a fixed plan, and measurable goals. Open Space is anything but that—it’s not planned in detail and it’s not centralized. It takes the self-organization and distributed way of working to the next level and unleashes the power of creativity of the system.

Organizational Open Space

Jutta Eckstein and John Buck, authors of Company-wide Agility with Beyond Budgeting, Open Space & Sociocracy: Survive & Thrive on Disruption

Today’s pressure on companies from VUCA and digitalization requires companies to be innovative at all times. Management typically assumes to be responsible for inducing innovation, for example, by inviting selected people to thinktanks. This approach misses the innovative power of the whole staff.

Open Space is a special events facilitation technique for achieving this increase in capacity. Organizational Open Space uses the same principles to leverage the innovative potential of everyone working for the organization every day—not just at special events.

For example, video game developer Valve Corporation invites staff to suggest ideas about a new game or improvements to existing games whenever the idea occurs to them during the work week. If there are any colleagues who believe in this new idea, they will join together to make it happen. Another example: at W.L. Gore (the outdoor equipper), everyone is invited constantly to suggest a new product, a new feature, or maybe even a new process. In both cases, if enough staff are interested in implementing this product, feature, or process, that interested group will pursue it. If there is not enough interest for the idea, the idea dies because the missing passion signals that it is probably not worth implementing. The opposite is also possible. If staff tires of an activity, they can stop doing it, so long as they take care of existing customers.

Innovation no longer relies solely on assignments via job descriptions, or on a few “innovative” people (like the R&D department), or on specific events like thinktanks. Innovation happens all the time by everyone.

Diversity of Roles

Every individual has different preferences, and flexible formats such as Open Space need to accommodate diversity and make it a guiding principle. That is why, besides the facilitator (the Open Space host) and the participants involved in discussion circles, Open Space defines two roles—Bumblebee and Butterfly. These roles simply describe the way you use the Law of Two Feet when you leave a discussion that lacks value or relevance for you and join a new one or when you just need a quiet moment to digest what you’ve learned.

Bumblebees fly freely from one group to another. They always listen to a piece of conversation and then jump to the next group and conversation. It often happens that the inspiration they have acquired in one group is transferred to another and makes a bridge between conversations. Bumblebees are like a last-minute spice, added on a whim, that turns a mediocre meal into a culinary delight. That’s what a Bumblebee does—on a whim, it lands in a topic circle and sometimes creates a buzz. It can’t be planned. It’s emergent, based on the situations and context. The randomness of it feels weird in the traditional environments but works great in complex systems.

The second role is the Butterfly. In contrast to Bumblebees, Butterflies are not participating in the planned conversations but create new opportunities to connect and learn. Sometimes they overhear something, and they need to keep their thoughts straight, so they sit somewhere alongside active conversations and take the time to reflect. Sometimes it happens that other butterflies sit down and create a totally unplanned group on the current theme. They are the most decentralized and disorganized part of the Open Space, living the principles: Whenever it starts is the right time, whoever come are the right people, and most important, whatever happens is the only thing that could have.

Open Space’s flexible format accommodates any idiosyncrasies in your preferred way of thinking, learning, and conversing. Consequently, it’s a great tool for addressing complex problems with creative and innovative ideas. It’s a completely free format, so don’t be afraid to be yourself. Remember, during the Open Space, whatever is happening is the right thing. You’ll see that once you get familiar with it, you will become a great fan of Open Space.

What You Need to Prepare

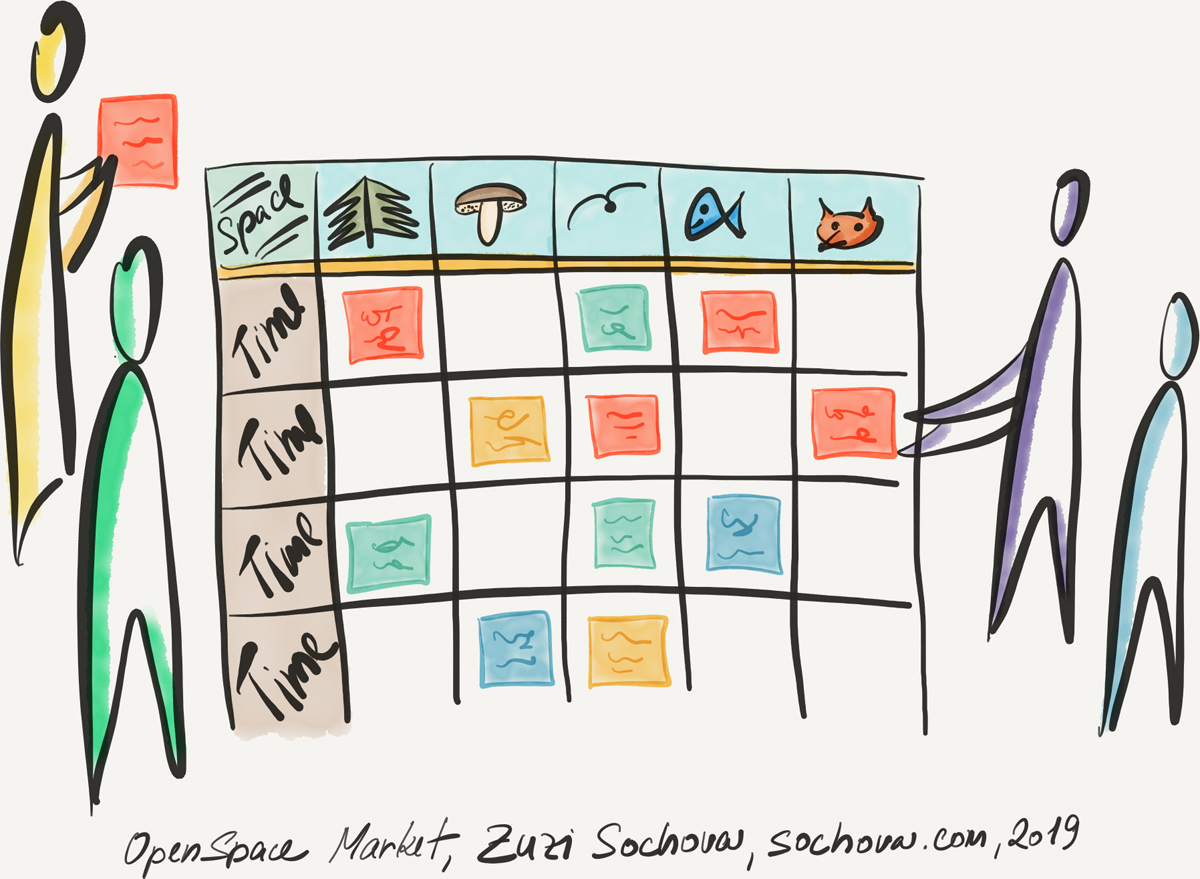

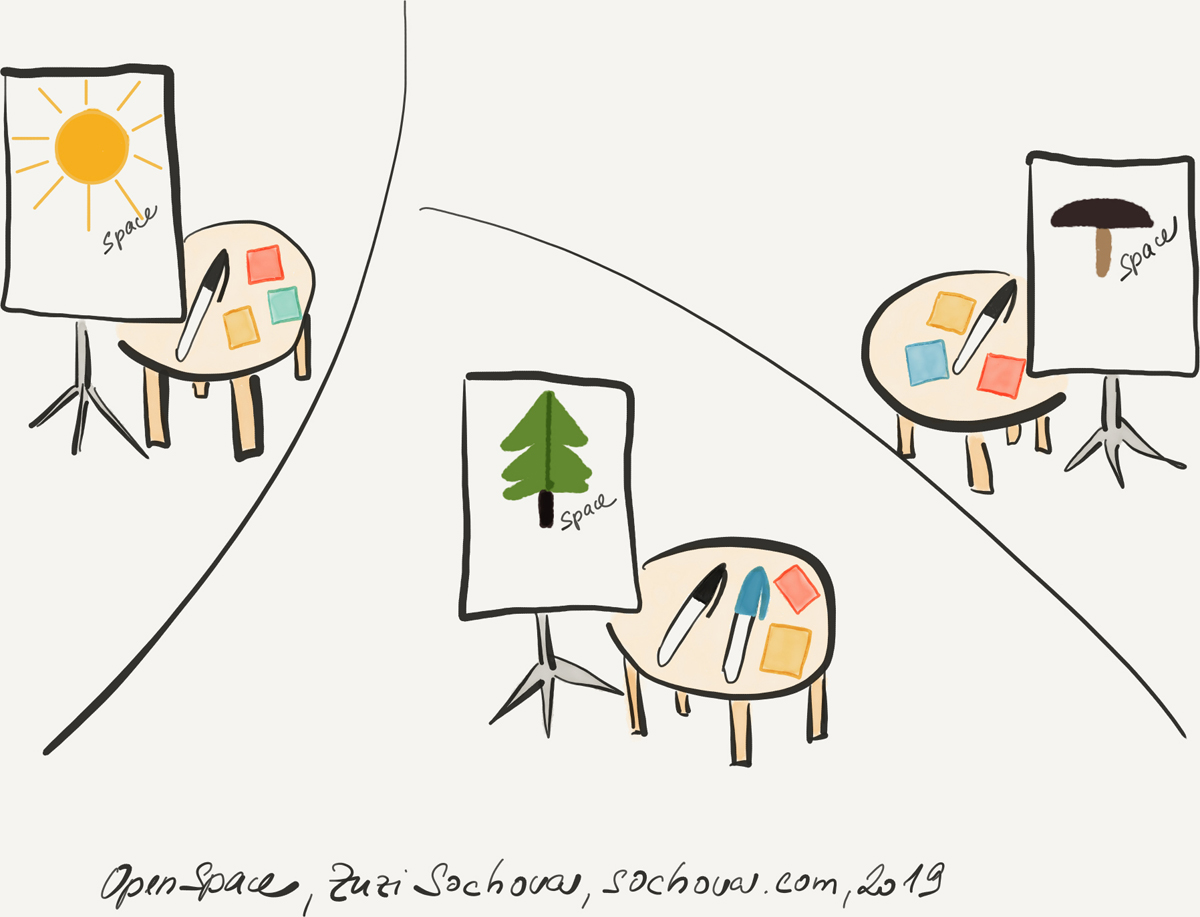

Let’s now take a look at what you need to prepare. You need a big room where the so-called marketplace will be held, and you need ideas for conversations. It’s not hard to arrange—just arrange chairs in a circle, or in several rows for a larger group, with enough markers and paper in the middle. The Open Space facilitator explains the rules and principles, reminds the participants about the theme of the day’s Open Space, and opens up the marketplace to ideas. Then, one by one, the participants present their area of interest to the others, write the topic and their name on a piece of paper, and place it on a specific space and time on the board to reserve a timeslot.

Sometimes, topic owners agree to combine their conversations if they have similar topics, and sometimes they change the timeframe at the last minute to be able to participate in a competing conversation about another interesting topic. Anyone who has suggested a topic may present his or her own idea or just facilitate the discussion among the participants and leave the ideas to them. There is no limit to the form. Each site has a flipchart to allow participants to record substantial conversation points so that the outcomes are not lost. At the end, everyone meets again, and someone from each group presents a summary of their conversation. Note that Open Space usually provides a forum to start a conversation about a certain topic—it’s not intended for participants to make big decisions; however, different experiments often emerge from Open Space conversations.

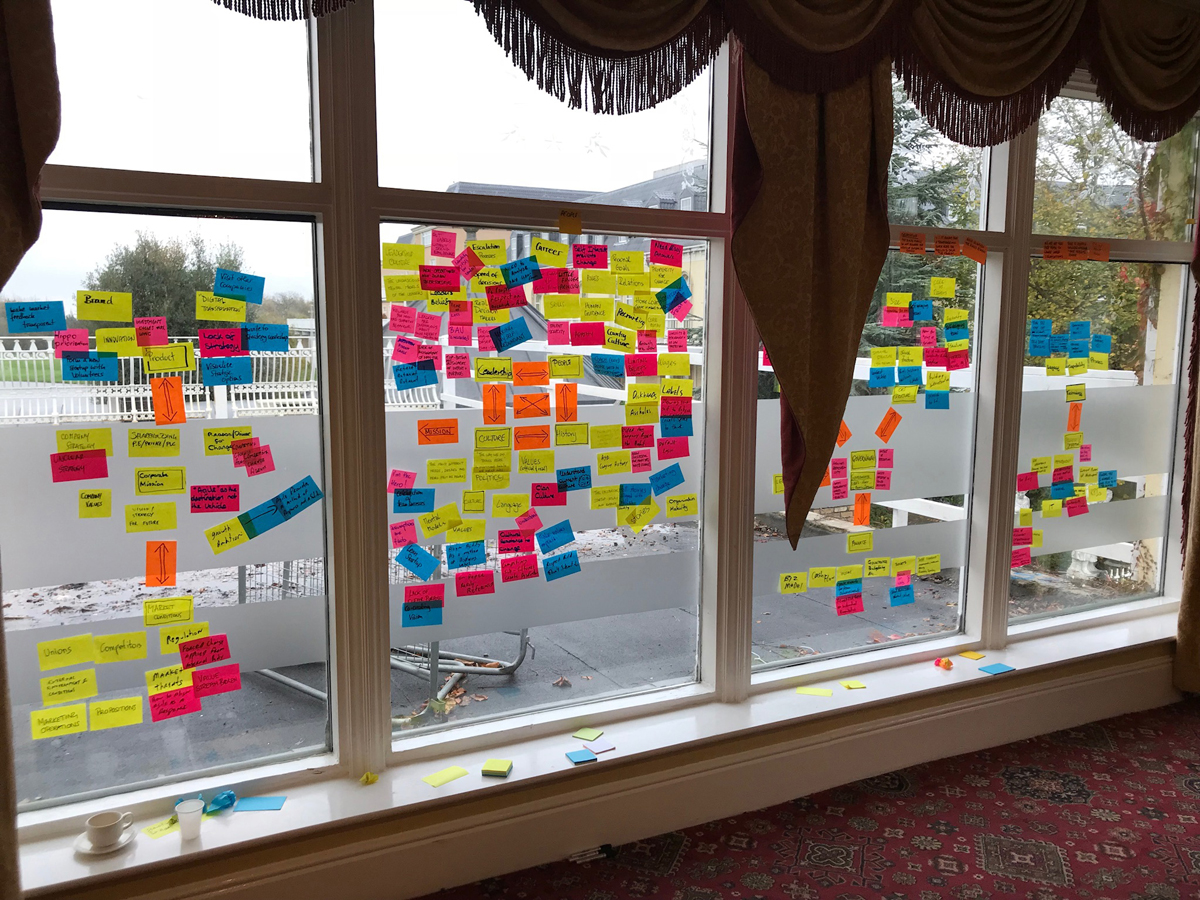

Example of Open Space marketplace from Agile Prague Conference 2017

Where Organizations Can Use Open Space

Once you understand what Open Space is, it’s time to consider where organizations can use this format. Open Space is often used at conferences to bring the experience of lectures and workshops to a concrete level, giving everyone the opportunity to discuss their particular problem and to be inspired by what interests others. The largest Open Space group I’ve seen was about 1,200 people; companies that organize Open Spaces regularly often have hundreds of participants. The number of people is not the limit here, as Open Space scales pretty well. All you need is to have a big enough room to run a joint marketplace and enough separate locations to have separate conversations.

So where is this format typically used? Basically, wherever we are dealing with a complex problem and are ready for real self-organization. Bringing together a large group of people is a great option to generate creativity and innovations and to brainstorm possible solutions to the problem, such as how to change the evaluation system; what types of goals, objectives, and measures we should have; what the new office space should look like; how to improve quality; how to get better access to the customers. It can also be used for Product Backlog refinement1 or an organizational retrospective.

Open Space builds on emergent leadership. When you are interested, you stand up for it, take responsibility, and try to form a group of people around you who are also interested in the topic. It raises transparency, and it’s voluntary and inclusive. It enhances the collaboration and creativity and thereby the overall agility of the organization.

The first time I participated in an Open Space was sometime in 2003, when our customers wanted to change their style of work. It was a few years before we had implemented Scrum and become agile. At that time, the customers just wanted to invest a hundred days in a better way of working. It was called “100 days of improvement,” with teams working for one hundred days to improve processes, infrastructure, automation, and so on. The hundred days started with an Open Space, where we all brainstormed what could help us in product development and how we could invest the one hundred days to improve in the most efficient way. It was weird at the time; we were confused and wondering why they let us talk without any predefined structure. But the ideas that came from that day were great, and we improved several parts of the system, which brought great business value afterward.

A few years later, I used Open Space workshops for an overall HR change, to improve the people development system, to design a new bonus structure, and to redesign our office space. At the product space, one of my favorite workshops facilitated by Open Space is the overall retrospective, where teams that work together on one product think of how they could improve teamwork. You would be amazed by the brilliant ideas that can emerge from pure self-organization.

How to Start

Let’s now see how to get started. Don’t be afraid. What emerges from Open Space does not necessarily have to be implemented in that exact way. What one working group suggests is just a beginning. It might be a long way to go to convince the others about the idea, evaluate it, and implement it. Well, it doesn’t have to be long, but what I want to emphasize is that what a group of people proposes is not automatically a decision. Sometimes, when there is agreement, a change can take just a few minutes. Other times, the final implementation takes months because lawyers need to get involved, finance needs to review it, and other departments have to finalize it. And sometimes an idea is never realized if it’s not practical from the organizational perspective. It doesn’t matter, because it’s about finding creative solutions to a complex problem, and that takes time and a series of experiments.

Open Space is a voluntary format, so it has enthusiastic people from the start and does not have to deal with demotivation. It is a format that builds on diversity and allows people to focus on the part of the problem that seems most interesting to them and try to move a bit together. The rules are simple and familiar to people with an agile mindset, and in an agile organization, the workshop will run almost by itself. In a traditional organization, where people still have the feeling that you need to have reporting and central management to do anything, Open Space usually makes people nervous and someone in the management stops it. “What if employees come up with something we don’t like, then what? It’s better not to let them do it at all.” Although facilitation is simple and the workshop itself cannot go wrong, some organizations and managers see it as a no go. After all, it’s an advanced technique of the agile world.

Agile Prague Open Space conversation about a topic

Let’s try this simple assessment. By evaluating responses to your idea to run an Open Space, you can tell if your organization is agile or not that much yet. Imagine a similar conversation in your organization:

“We would like to organize a half-day workshop on how to improve ______. ______ is our biggest problem. It costs us ______ in time and money monthly, and so far, we haven’t been able to improve it. We would like to invite all team members to think about what we can do about it in an Open Space.”

What will be the reaction in your organization?

0: “Don’t even think about changing it. No change is possible in this area. All you have to do is to follow the processes.”

1: “How much will it cost? We can’t give it half a day—we have to work and deliver.”

2: “You can’t invite everyone. If you really want to do it, create a small working group.”

3: “Is participation really voluntary? And what if . . . ?”

4: “Let me know how it went.”

5: “Can I join as well?”

It’s a simple test. Ask people around you and classify their answer according to the 0 to 5 scale. The number of points you get on average shows how agile your organization is:

0 means your organization is not ready for such agile practices and is deep in the traditional mindset. I would start with something smaller to show the organization that self-organization and decentralizing work can be successful.

3 gives you a chance to try, though you will have to explain it a lot and also increase the safety. When you sell the first such workshop within the organization as a success, you usually have a win and you will be allowed to use it again from time to time.

5 is a sign that you have gone quite far on your agile journey and agile is part of your organization’s DNA. Agile is not only what you do but how you live. Open Space workshops will become a normal part of your organization, and other people within the organization will start organizing them whenever they need to address some complex problem.

Anything in between these thresholds shows you are already on the way to reaching the next level.

What can you do to increase the readiness of the organization to try the Open Space format?

World Café

World Café is another great tool for raising awareness about a topic. It’s great for scaling a conversation and leveraging the wisdom of the system. The setup is very simple: people sit in small groups around tables, like in a café, so they can have a conversation in a comfortable way. Usually, each table has a flipchart or just a set of larger Post-it Notes and Sharpies so people can make notes from their conversation.

The World Café starts with the facilitator introducing the format and setting the expectations for it. World Café is a great tool to address the first step of the agile leadership model: get awareness. It’s not a tool for making fast decisions, but it helps large and diverse groups to reflect on the current state, listen to the voices of the system, and become aware of the different perspectives.

Initially, we ask people to form cross-functional diverse teams, to cover as many perspectives as they can. We usually run three (or more) 20-minute conversations about the topic, where each conversation round is framed by a question. The questions don’t cover three different topics but instead look at the same topic from three different angles, to help people investigate the area from different perspectives and listen to the voices of the system.

In every round, the group selects one person who stays in the group and at the beginning of the next round explains to the new participants the bottom line of the previous conversation. The flipchart is a useful visual tool for that. The rest of the people randomly choose a new discussion table to join, keeping in mind the diversity and cross-functionality of the groups.

After the last round is done, the groups present their outcomes to others and look for action steps.

Agile Lean Europe Network Vision

My first experience with World Café was at the Vision/Purpose session of ALE, the Agile Lean Europe network2 at XP2011 in Madrid (you can watch the video from the session).3 We used Lego StrategicPlay4 to help creativity flow. It was an event where agilists from thirty-two countries came together and used the World Café format to discuss possibilities for the Vision of the newly created ALE network. Creating a community vision is anything but a straightforward process. Everyone has an opinion, and everyone is right—but only partially. The World Café created the right diversity mix, while Lego helped us to go through the three levels of reality and leverage the power of sentient essence and dreaming before we brought it back to the consensus reality. Every group proposed a vision, along with an explanation of it. In the end, Jurgen Appelo, who initiated the idea of creating the ALE network, was able to compile the vision: “The Agile Lean Europe (ALE) network is an open and evolving network of people (not businesses), with links to local communities and institutes. It helps people in European countries by spreading ideas and growing a collective memory of Agile and Lean thinking. And by exchanging interesting people with diverse perspectives across borders it allows beautiful results to emerge” [ALE11]. It was almost magical how all the diverse voices unified after the session around one coherent vision statement.

Example of Lego StrategicPlay for ALE Network, XP2011 (Photo Ralph Miarka)

Awareness about Processes

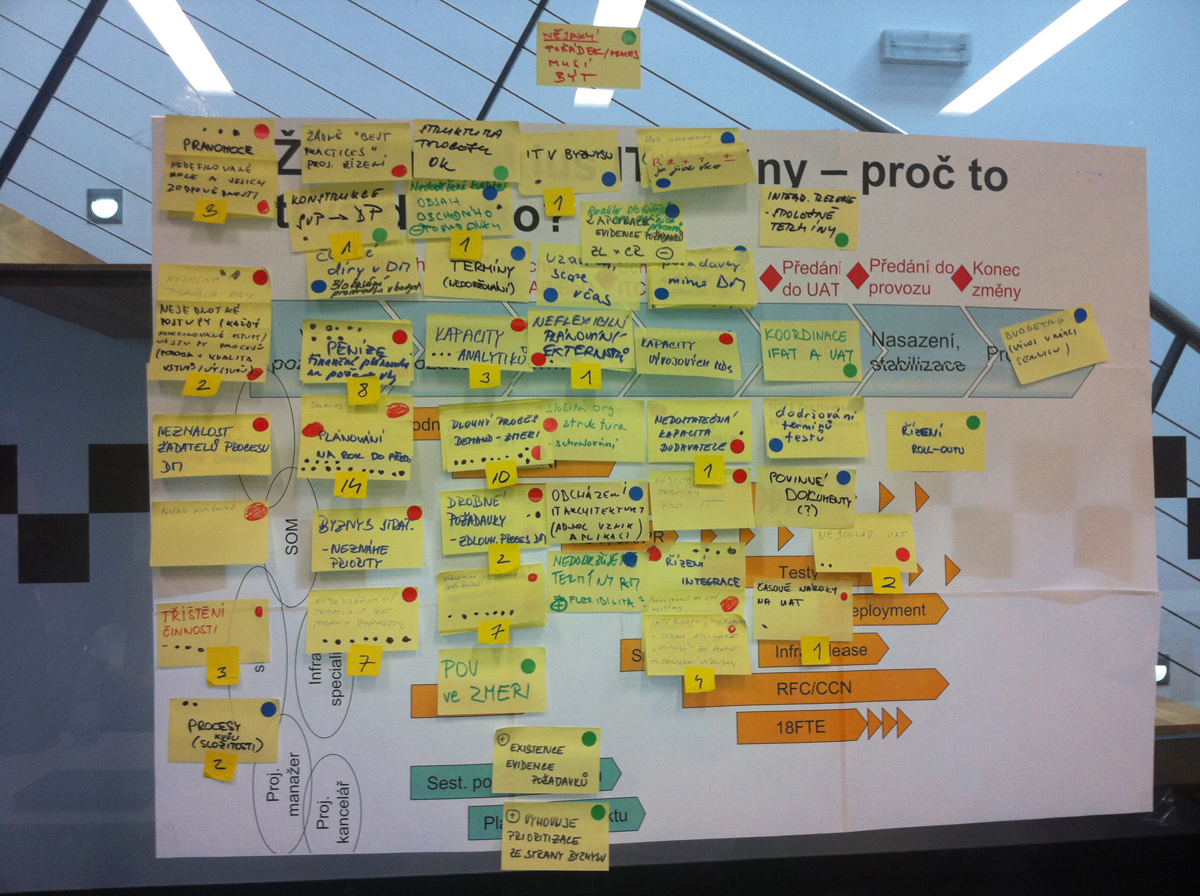

Another example is from a corporation where we invited about one hundred people and facilitated a discussion around how their current business process mapped against the formal process description and how it could be changed. We printed a big poster of the existing process and put it on a wall, and in three rounds let people investigate the differences between how it was used and how it was described, the obstacles they were facing, and the areas they wanted to keep unchanged. During the conversation, we mapped the current process to the picture representing the formal process to visualize the differences, and we concluded the workshop with a conversation about how we should change the way we work.

Example of the outcome of World Café mapping the existing processes to the expected way of working

Expectations from the Roles

The third example is from an agile organization where we needed to raise awareness of different mutual expectations from the roles of ScrumMaster, Product Owner, and Manager. We had three rounds of questions: “How can the ScrumMaster help the Product Owner and Manager?” “What can the Product Owner expect from the ScrumMaster and Manager?” and “The manager is primarily a leader. How does my leadership affect the ScrumMaster and Product Owner?” No decisions were made that day, but several ScrumMasters, Product Owners, and Managers left the room with the action item that they needed to have a deeper conversation and get aligned, as they realized their expectations didn’t match. And that’s exactly where the World Café is often used—to start the conversation and raise awareness.

As you can see from the given examples, the World Café is a very flexible format for sparking the creativity of the system. You can use it to address any complex problem, but it would be a waste of time on predictable problems where the solution is easy to figure out.

Systems Thinking

Tools such as systems thinking are interesting in the modern world, as they don’t avoid complexity but show it in its entire ugliness so we can deal with it. The fundamental belief behind it is that everything is part of a larger whole and that the connections between all elements are critical [Acaroglu16], and therefore you need to be aware of the whole system and its complexity. To visualize the complex system, we often use the causal loop diagram [LeSS19b], which creates a great opportunity for conversation and collaboration. There is no right or wrong in the complex system, just different perspectives, and the causal loop diagram is a good visualization technique to start seeing them and initiate a conversation around them. While it’s a good technique for running a workshop, it’s not intended to be self-explanatory once you see the result.

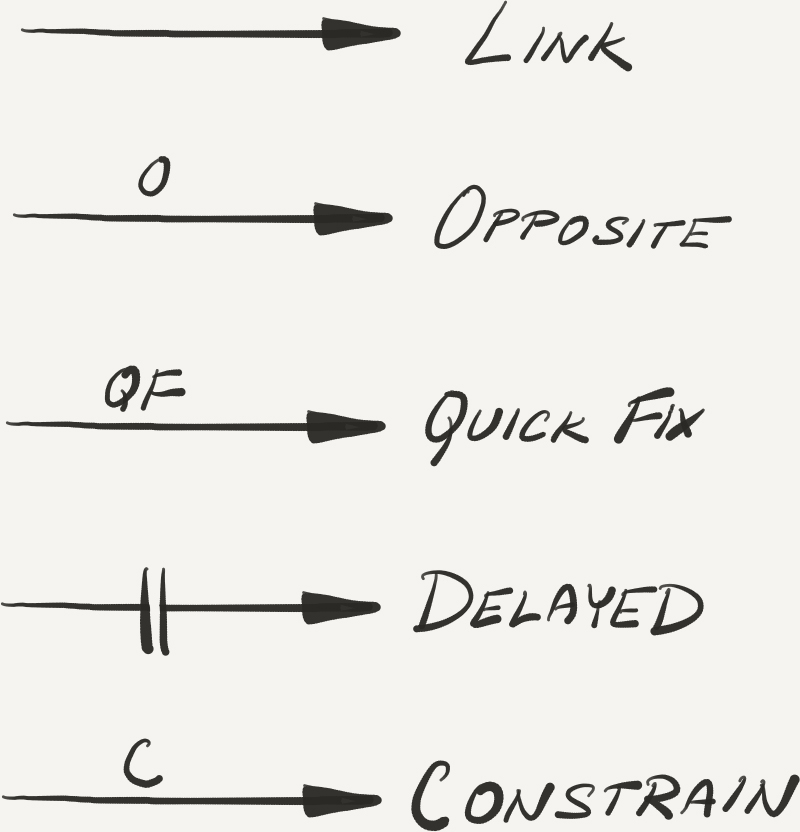

Causal loop diagrams are easy to start experimenting with. As you can see, the syntax is straightforward. We have a simple arrow to represent the causal link of how one item influences another, as well as the opposite effect—links representing constraints, quick-fix reactions, and delayed reactions.

As mentioned, this technique is easy to start with, but you need some practice to make sense of it. Remember, it’s not a tool to show you one way to go but instead to help you visualize the interconnectedness and the overall complexity so that you can have a conversation about the complex system while drawing it.

Example of the systems thinking causal loop diagram

Systems Thinking to Discover Conflicting Optimization Goals

Jurgen de Smet, Cofounder of Co-Learning

I have been supporting many large organizations with becoming more agile, and one of the major things one has to do in this context is redesign organizational structures and processes. There was a time when I was helping an organization to adopt LeSS Huge within the boundaries/mandate provided, and the managers providing support were struggling to connect to their existing project management office. Exploring the issues, I suspected that the project management office (PMO) had optimization goals conflicting with what we wanted to achieve with the research and development (R&D) and product marketing group. In order to validate my suspicion, and provide a higher level of transparency on the optimization goals of the systems in place, I organized a systems modeling workshop with representatives from the PMO, R&D, and product marketing departments.

Instead of creating smaller groups with a high diversity, which I do in most of the systems modeling workshops I design and facilitate, I went for groups that represented their departments. I had a group of project and program managers, a group of product marketeers and managers, and a group of engineers. The groups were guided to define their own system variables they cared about within the context of their organization. They then modeled the relationships between their own variables and chose their own, single optimization goal that was, for them, crucial to being effective in their context. With the optimization goal identified, they evaluated the impact on their system variables and thus acquired a good understanding about the why of everything they do and were changing. At the end, we had the three groups connect the three different models to each other, as everything is connected to everything. They discovered that the optimization goal set forward by PMO was conflicting (not consistent) with the optimization goals set forth by product marketing and R&D. Through having a higher level of transparency on their system design, their PMO decided to change gears and adapt to the optimization goals of the others. The result? Less frustration and fewer conflicts in the day-to-day operations and a faster change track.

Radical Transparency

Transparency is the key building block of any agile environment. It looks simple, but it’s very hard to practice in traditional organizations, where the competing environment makes people extremely protective as they believe that whoever has information can make a decision and therefore owns the power. Let’s be truthful for a moment—how many organizations that you’ve worked for have real transparency, and how many are hiding information behind team or department walls, encouraged by processes and claiming the necessity of compliance? Lack of transparency is a strong weapon that eventually can kill any agile transformation, as it makes collaboration and self-organization almost impossible. Lack of transparency is a great friend of hierarchical structures supported by fear and politics. “If I’m the only one who has the information, no one can jeopardize my position, and I’m safe in my position as manager. All I need to do to be promoted is wait and make sure that no big mistake happens.” Sound familiar?

Radical transparency is the key enabler of agility.

When you move from a hierarchical individual culture to a team-oriented culture, the information needs to flow at a much broader level. Once you are committed to your agile journey, radical transparency is the key enabler. Together with the empowerment resulting from self-organization, it energizes people, and they start to take over responsibility and ownership. They don’t wait until someone promotes them to a specific function, and they don’t wait for orders. They take over and collaborate on the solutions.

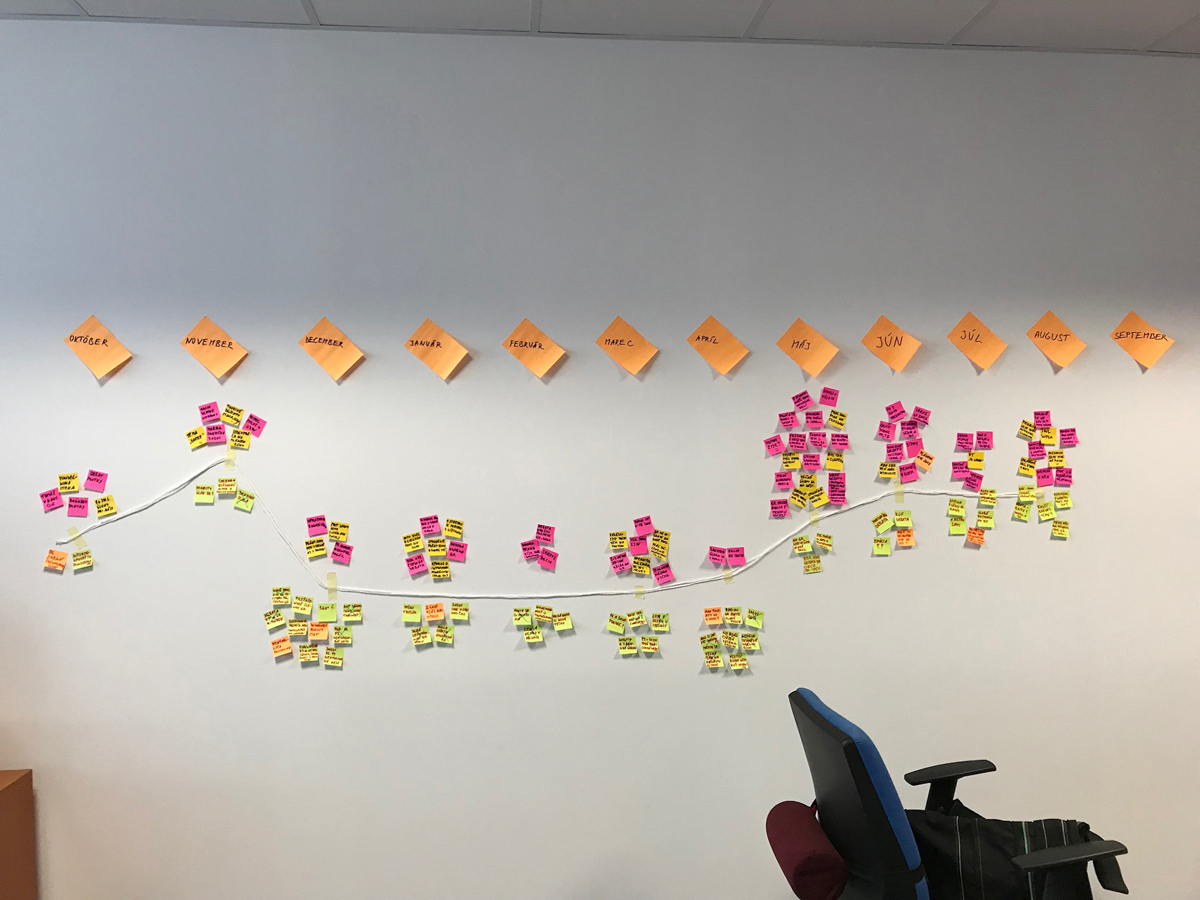

You can also make your monthly agile journey retrospectives visible on the wall.

Transparency doesn’t have boundaries. It’s not about tools. You can start by sharing Post-it Notes and visualizing the obstacles along your journey, making transparent the actions from the retrospectives or positivity charts—the only limit is the wall space.

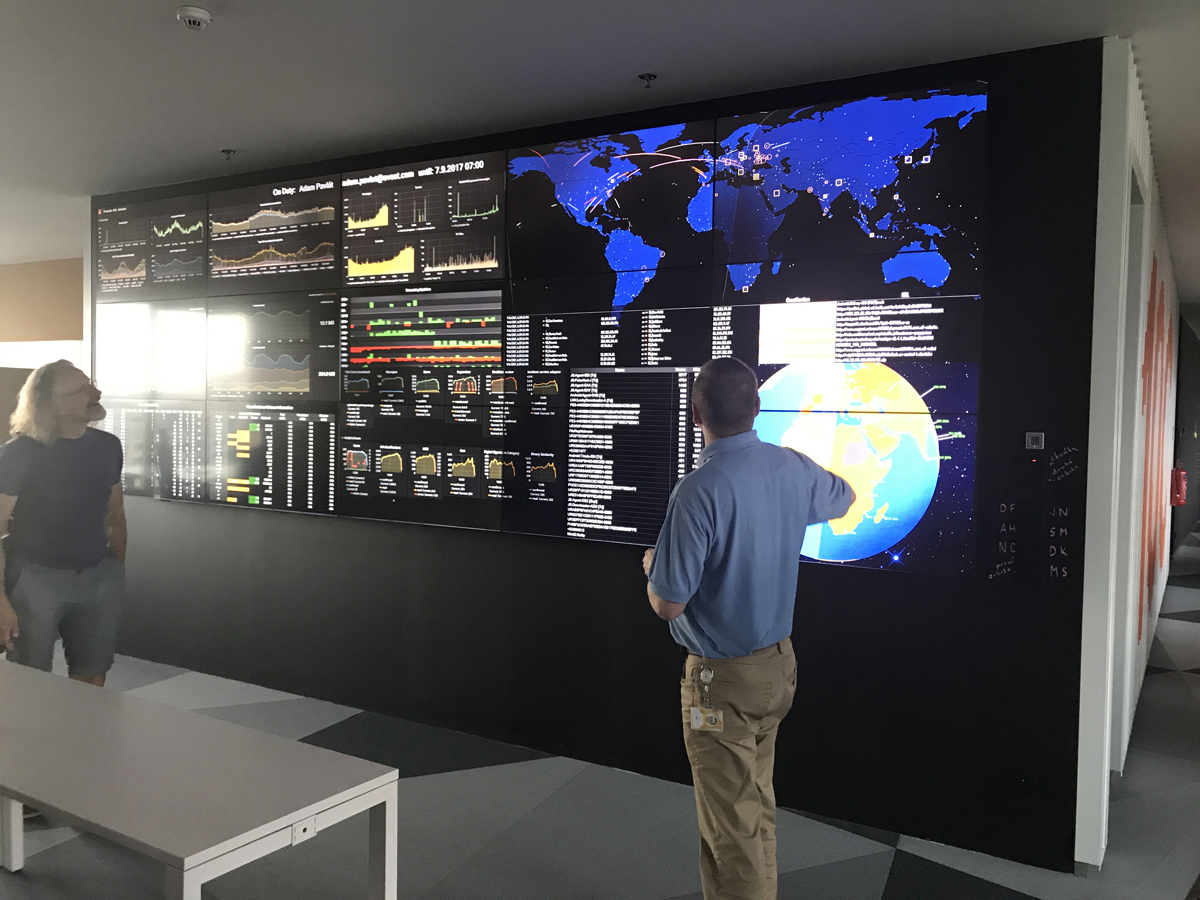

Result of large group refinement workshop

You can implement real-time visualization and show the real-time data from your system performance and be more business-driven. Leverage the continuous delivery and fast feedback to see right away what feature created an intended impact and what feature did the opposite and needs to be changed.

Make all key business indicators transparent.

Radical Transparency

Eric Engelmann, Founder of Geonetric, Iowa Startup Accelerator, and NewBoCo, Board Chair at ScrumAlliance

My team explored radical transparency at Geonetric, opting to construct fully empowered, self-organizing teams with minimal hierarchy. I had noticed that small cross-disciplinary teams working on a clearly defined and focused goal could accomplish incredible things very quickly, and I decided to build a culture and even an entire company around it.

We created as much transparency as we could imagine—financial data, operational data, customer data—and asked the teams to respond to and prioritize their work using it. I had imagined that these changes would be mostly “operational”—in how the work got done. But it eventually became the core culture of the company, in every team: we had to change how we marketed and sold our products; we had to rewrite our approach to attracting and retaining talent; we had to revamp our accounting systems. All of these things combined changed our company strategy and our position in the marketplace, too.

From those early glimpses of agile success through fully embracing it as a company, we had no idea how deep the rabbit hole went—there was always more to learn and explore, no matter how radical the changes felt at the time. And there’s still more to discover.

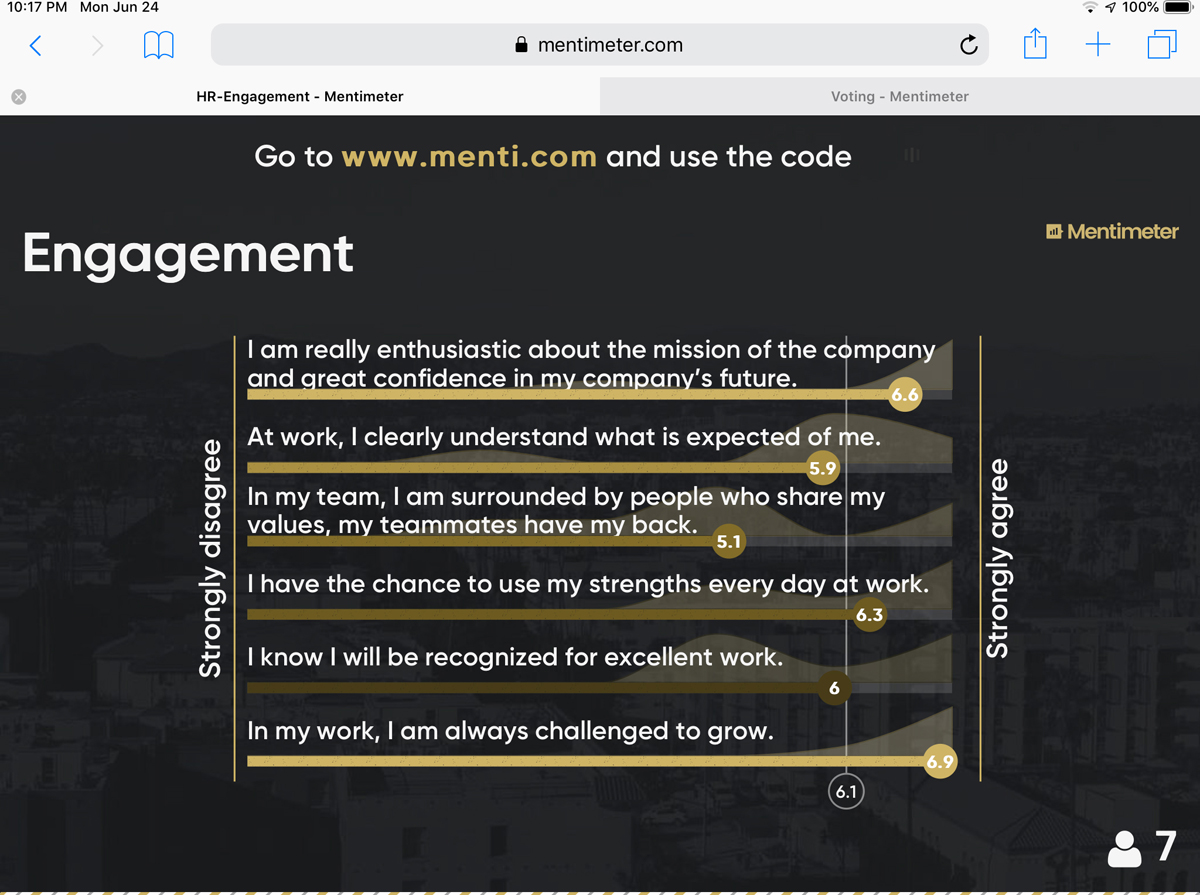

Nowadays, technologies help us to address transparency from new angles. Different online voting and survey tools5 help raise system awareness about new perspectives and can make a difference even on a topic as complex and hard to describe as a culture. No matter where your participants are located, they can see the real-time results. It’s fast, easy to use, and transparent. However, be aware that all such tools do only the task of data gathering and would not solve the issue itself.

Example of Engagement survey results using Mentimeter online tool

Radical transparency is about showing everything, including sharing information about your business with the world. Some organizations blog about everything they do. One example is Dodo Pizza6—you can see the company’s finances online, read about its Sprint reviews, and follow its journey. Dodo Pizza is not afraid someone might steal some secret information and compete with it. The company has embraced radical transparency and everything that comes with it. Another well-known example is Buffer.7 It has moved transparency to the next level and shares all revenues, salaries, pricing, and product roadmaps as well as emails, how company personnel travel, and how they work as a remote team. Quite radical, you might say. Radical transparency gives Buffer the opportunity to learn faster. As its director of people, Courtney Seiter, says, “We learn so much faster than if we were to keep things to ourselves. We’re able to gather all that information that’s sort of wisdom of the crowd.” Radical transparency is only one of Buffer’s core values [Seiter15], and I would say that together with its people-oriented culture, transparency makes the biggest difference. “As long as we all share information, what’s going on in our email, what’s going on in our projects, or what’s going on in Slack, that gives everyone full context to make connections we might otherwise have missed” [Cherry18]. Slack is, by design, a transparent tool for communication, but imagine if everyone could read everyone’s emails and how that would minimize any attempt to engage in politics or be manipulative, since everyone can see everything. As Ray Dalio, another promoter of radical transparency, says, “The most important things I want are meaningful work and meaningful relationships. And I believe that the way to get those is through radical truth and radical transparency. In order to be successful, we have to have independent thinkers—so independent that they’ll bet against the consensus. You have to put your honest thoughts on the table” [Hammett18].

Relationships take time, and so does radical transparency. At the end of the day, time is the only downside. Like every culture change, it’s hard to hardcode it in your behavior. As Courtney Seiter shared, “You really have to set aside time and keep making it a priority and keep making it something that you communicate” [Seiter15]. You also need to be ready to have a candid, open conversation and have the courage to voice constructive criticism and disagree with your colleagues.

Other organizations are running tours to let people experience what it is like to work there. The most famous example is Zappos.8 Zappos runs tours of its building in Las Vegas, Nevada, to show the world its culture.

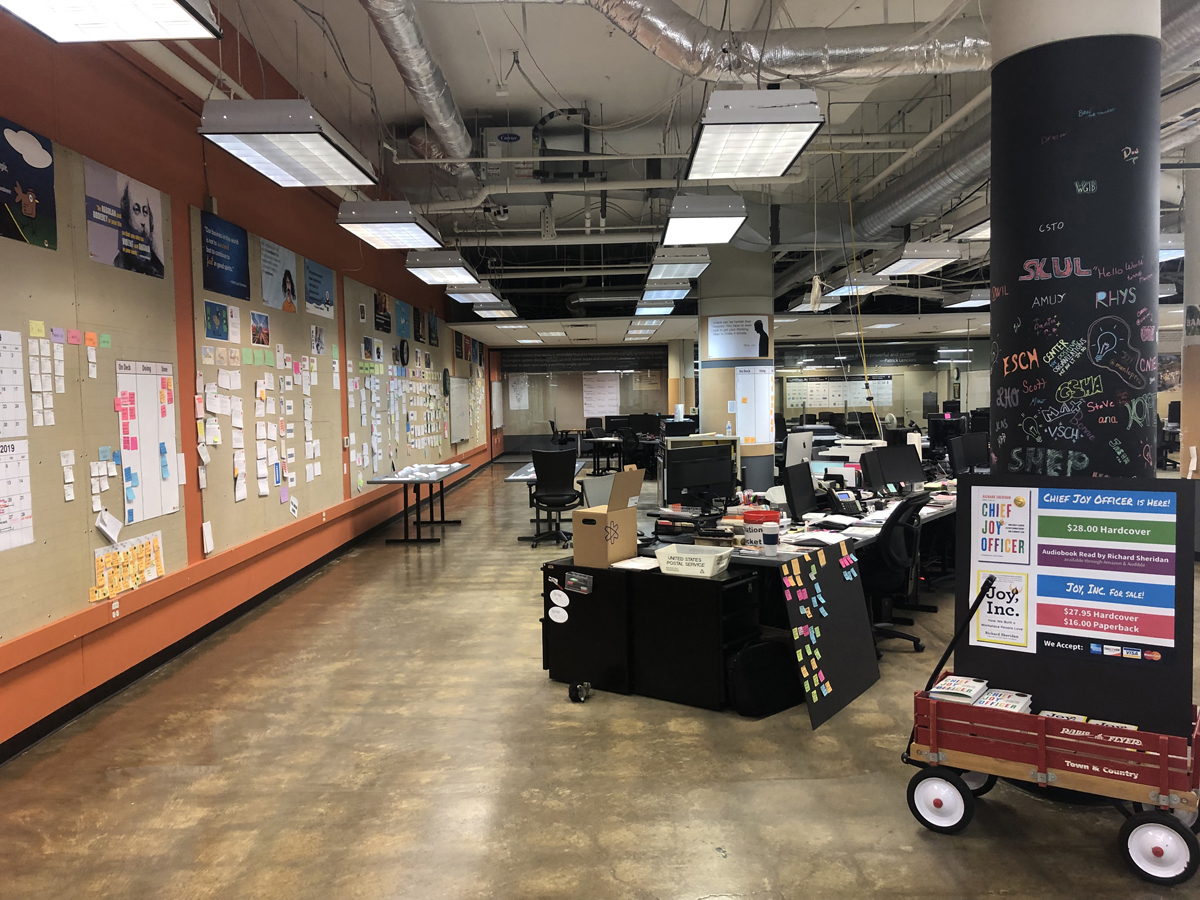

Menlo Innovations Collaborative Space

I recently visited the Menlo Innovations9 offices in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and spent two days there. The level of transparency was outstanding. Indeed, you can see all the backlogs and story maps all over the walls and experience its huge organizational Daily Standup where everyone shares what they did and are going to do, but my favorite was the wall with all the people and their positions. Everyone can clearly see where they are and who among their colleagues can mentor them to grow. As everything is transparent and linked together, the Levels Board shown in the following photograph is visible to everyone and also determines their salary. Every column shows the maturity level and every box creates an experienced step on the learning journey.

Menlo Innovations offices and transparency about levels

Using a Transparent Pay Scale to Provoke Growth Opportunities at Menlo Innovations

Josh Sartwell and Matt Scholand, Menlo Innovations

It was Friday evening, and Tim took a quick stop at the Levels Board on his way to the coat room. He’d spent the past week working with Sam and wondered what level she was. He looked for her initials in the Consultant column. He couldn’t find her. Then he looked at the Associate levels, and found her at level 3—below a consultant. Surprised, Tim reflected on the week’s work. What stood out to Tim was Sam’s exceptional skill in consulting the client on a difficult and expensive project decision. Tim was very grateful to have had Sam in those conversations.

While he was looking at the Levels Board, Kelly, a project manager, came up and asked him what he was contemplating. Tim suggested that, based on what he had seen from Sam in the past week, he thought it was time to move Sam up to the consultant levels. Kelly hesitated, then asked, “How do you think Sam would do with a technology that’s new to her?” Tim thought for a moment and realized he didn’t know. Kelly acknowledged that Sam demonstrated consultant-level skills in a number of ways, but the project managers were not comfortable putting her on a project with an unfamiliar technology, since she hadn’t demonstrated an ability to make progress and pick up new things quickly. That led Kelly and the other project managers to believe that Sam wasn’t operating at a consultant level.

The following week, Sam agreed to a short feedback session with Tim and Kelly. Tim shared his appreciation for the work Sam had done and the value she brought in their week of being paired together. He expressed his desire to move her up in order to recognize this value, but her skill set in working in unfamiliar technologies was holding her back. Sam understood and explained that her discomfort around unfamiliar technologies was rooted in a fear of letting the team down. The three of them discussed the issue and advocated for the project managers to pair Sam and Carl, another developer good at diving into unfamiliar technology, on a different project with a new technology in order for Sam to grow her skills with Carl as a mentor.

In an organization where growth opportunities are discussed once a year and employees are evaluated by people they don’t work with, Sam might not have received the immediate feedback and support she needed to grow professionally. Without transparent levels and pay scale, Sam’s team would not have had the opportunity to realize her growth potential. The transparency provided by the roles and Levels Board at Menlo is a catalyst for conversations that are needed in order to help employees and the business thrive.

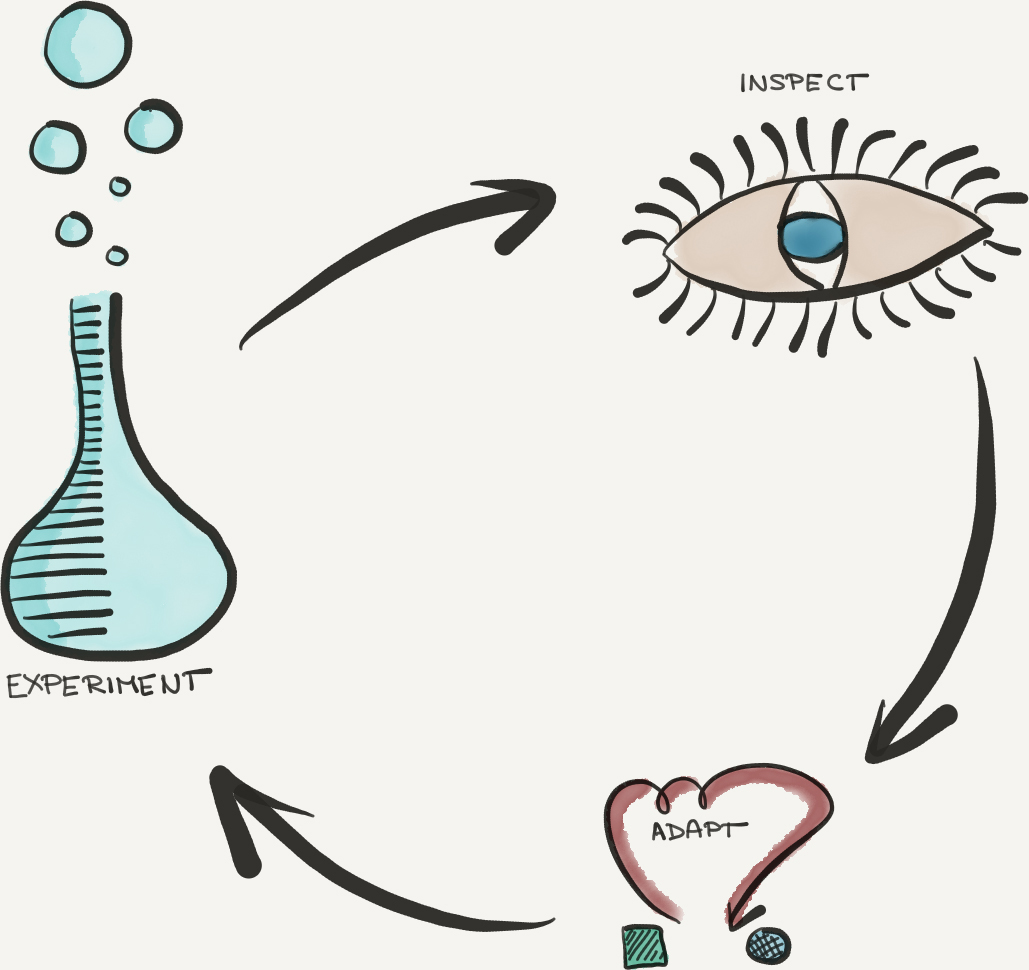

Experiment, Inspect, and Adapt

The next step on the radical transparency journey is to run experiments. At every level, you need to be transparent, openly share experiments at the early stage, and be ready to adapt on the basis of feedback. Though you can apply it to product development, the process is applicable to the entire organization. The downside is that before you learn how to collaborate and confirm that you have the same understanding of the vision, it’s going to be very inefficient. And very frustrating. “If we can just do it our way,” “They don’t understand it,” and “We know what to do, so why should we ask for feedback?” people often say. But if you are strong enough and stay away from shortcut prebaked solutions, very soon you will see the results in higher collaboration, better understanding, and harmony, which together contribute to a high-performing environment.

Run regular retrospectives and be transparent about action steps. Share the backlog internally and externally. There is very little information—if any—that needs to be hidden. If you believe you have found such information, double-check it by applying the Five Whys10 technique, and make sure you have a plan for what needs to be done so you can make it transparent in the future.

When we decided to move toward a different way of running performance reviews, we didn’t know if it was going to work, and I didn’t have a backup plan either. I wanted to make it simple, with as light a process as I could, based on transparency, peer feedback, and coaching. I wanted to stop evaluating and help people to grow and to find their own role in the organization. Initially, we started on a quarterly basis and ran self-assessment followed by a coaching session. We got good feedback from all the employees as we listened to their dreams and desires, but very soon we realized that this might be too much. We started doing quarterly peer feedback and had coaching conversations about growth on a yearly basis or when there was a specific need.

As everybody got to experience it and we built trust in the system, people started coming when they felt a need to talk about their value or development. We also realized that quarterly peer feedback might not fit every situation, so eventually we made it more frequent in some teams and left it open for every team to design their own process according to their needs. We also made the coaching conversation irregular—we just made sure we got to talk to people at least once a year about where they wanted to go, what they wanted to learn, and how they saw their role in the organization. The whole process changed significantly on the basis of the feedback: certain ideas were not practical (like assessing all the technical domains), and some were too radical at the time (like making the peer feedback fully transparent). We were not looking for a fixed process. Step by step, we iterated on transparency, learned from the feedback, adapted, and found ways to experiment. The idea of adapting the whole system built trust in the teams and made it easier for them to embrace the change, as even when something was not working that well, it was clear that it was not set in stone. Everything was just an experiment that could be adapted through the feedback loop.

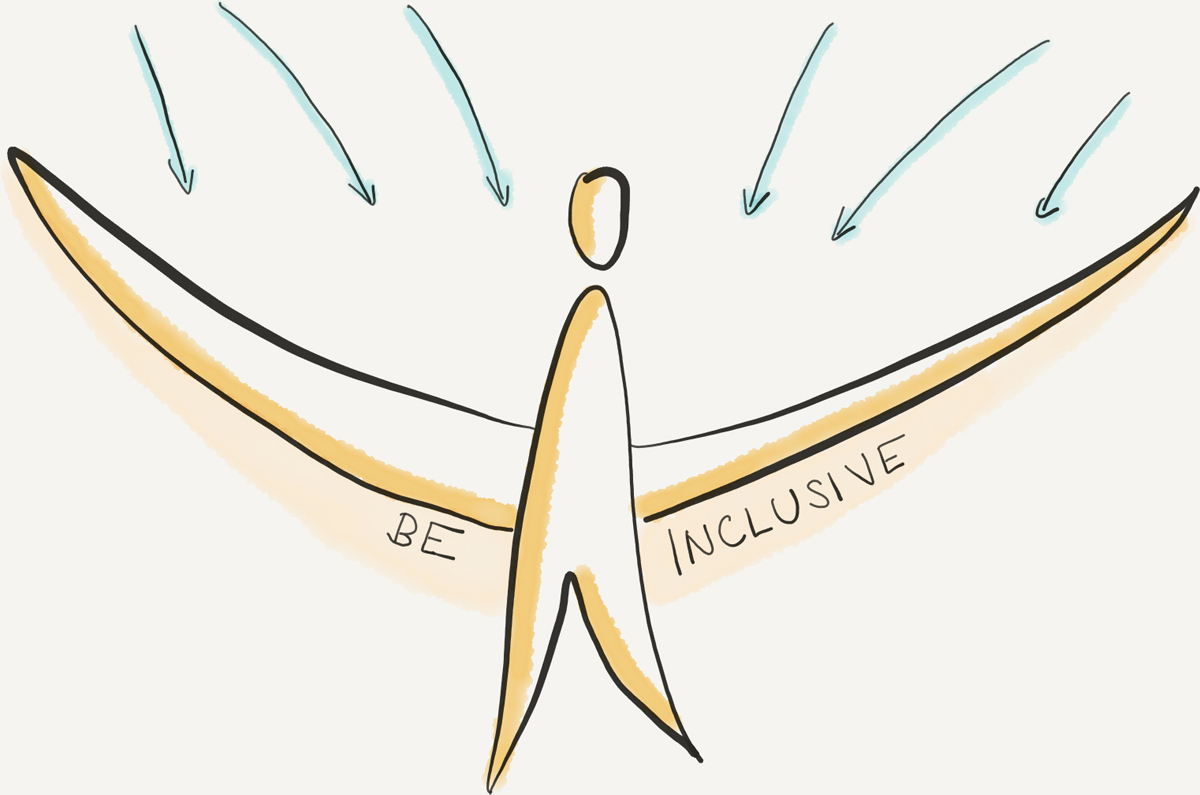

Be Inclusive

The last necessary step on the radical transparency journey is to be inclusive. There should be no such thing as a closed meeting. They should be publicly visible, with an open invitation so people can join if they are interested and have something to say. If there are a lot of people, the facilitator can use some diverge-and-merge facilitation techniques, but no restriction should be applied for the sake of efficiency.

It’s not about being fast without alignment; it’s about building alignment that allows you to be even faster.

One of the key parts of our culture shift was to be more innovative and creative. It was not that simple, as most of our employees were used to working according to strict requirements. They thought that in our business there was no space to be creative and innovative because we work in life- and mission-critical systems domain. Asking them to be part of the creative workshop and explore the potential of social networks, the internet of things, or autonomous systems sounded to them like language from a different planet.

Traditionally, building a new business pillar would work as a small pilot team isolated from the rest of the organization. We decided to do it differently: use the power of the system and make the whole initiative inclusive and voluntary. Participation varied; many people were skeptical at first, but at some point, we experienced an interesting shift whereby many different people you would never have expected to participate in such an initiative started coming up with new ideas, teams were trying new prototypes in their slack time, and the whole initiative was infused with new energy, which brought people who were initially skeptical back to the team. In about a year, one of the ideas was sold to a new customer. We used new technology, addressed a new business segment, and leveraged artificial intelligence experience in collaboration with the researchers. Through that experience, I learned that a volunteer-based inclusive approach is an enabler in many situations. Let the system self-organize and let the teams figure out what is the best solution to the problem. It’s not the most efficient way if you already know what the solution is, but it works incredibly well to crack the VUCA challenges.

Have Courage

Radical transparency is hard. You first need to have the courage to say how things really are, not be afraid to hear difficult feedback, trust that people will help you, and be ready to help others because, after all, you have the same vision and the same evolutionary purpose to achieve. It’s not easy, but it is a great investment, and it will pay back when you have formed a highly adaptive (agile), high-performing organization, one that is equipped to crack the challenges of our complex world.

From the following list, choose the item that most closely describes your organization:

In our organization . . .

People don’t need to know everything; the information flow is purely hierarchical.

We are transparent at the team level.

We have full transparency within the organization.

We are open to sharing information publicly within the network of our customers and partners.

We are open with other organizations and the world; radical transparency is our biggest competitive advantage.

The list starts from a description of environments with very low transparency and continues with higher transparency applied to the broader areas in the organization or even outside of the organization.

What can you do at your organization to increase the transparency?

Better to Ask for Forgiveness than to Beg for Permission

Jurgen de Smet, Cofounder of Co-Learning

Many people come to me for management support, asking how to acquire this in their context. The best thing I can come up with is to work from within the principles and not beg for permission. When done right, one will automatically have management support to get things to move forward. I was at the pub with some of my hometown buddies when this topic came up, and one of them challenged me to join his organization and he would show me, he said, that my statements were BS (not Basic Scrum). He arranged some budget, and I went to work with him and his team members; in this context, we had little to no mandate for true change, and many had the impression one could do only as much as the mandate allowed for. One of the first things I did was to synchronize their Sprint Planning and Sprint Review sessions across six teams, facilitating and organizing them in the same room with all the people involved. Yes, they all had their own Product Owner (well, team output owner) and their own Product Backlog (well, team backlog), of which they were not aware across the teams, but that didn’t matter to me. I considered them working on the same product, and by having Sprint Planning and Sprint Review sessions together, the team members started to notice they were actually working on the same product (I increased transparency, and the teams inspected and adapted). In Sprint 3 or 4, the teams did their Sprint Retrospective around the topic “Why are we not one team?” They came up with argumentation for the R&D director (the one with the mandate) to change their structures and work with only one Product Owner and from only one Product Backlog as if they were one team. Parallel to this, I connected with the head of product management, explored the problems he had, and helped him see the benefits of a single, outcome-based Product Backlog across the teams. So the R&D director got a request from product management to redesign their structures in a way similar to what the teams were asking for. There is no director or manager who will refuse to take an action when the request is coming from their own teams and from the business at the same time. Today, my hometown buddy is telling his own stories instead of calling my stories BS.

The key is to have the courage to work from within the principles and to increase transparency and awareness within the organization. The rest will follow! Don’t beg for permission: it’s better to ask for forgiveness.

Growing Trust

Trust is the key prerequisite for a well-functioning team [Lencioni11]. Lack of trust happens if people are reluctant to be vulnerable with one another; they are often afraid to ask for help, they hide their mistakes from each other, and they are reluctant to give constructive feedback. Quite a disaster, as there is no way people who don’t trust each other would collaborate on anything and be agile.

People usually think about trust in terms of predictability. If you can expect certain behavior from a person, you trust that he or she will do the same good job again. But that’s only the first step toward full trust. As Patrick Lencioni says in his book The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, vulnerability-based trust brings with it much deeper confidence: “In the context of building a team, trust is the confidence among team members that their peers’ intentions are good, and that there is no reason to be protective or careful around the group. In essence, teammates must get comfortable being vulnerable with one another” [Lencioni11].

Vulnerability-based trust is a prerequisite for high-performing teams. The environments with a high level of trust would embrace agile without a struggle. Let’s take a look at several tips on how to build trust.

Team Building

Team building is the most impactful trust builder. When people spend some personal time together, talking not only about work but also about life, their hobbies, ideas, and passions, they form close interpersonal connections. You can go for a beer after work, go bowling, try to “Escape the Room”11 together, take a trip together to explore, or just have a team lunch or spend time talking over coffee about non-work-related topics. Some teams play a game of “Tell me something that people don’t usually know about you and it’s not a secret.” You would be amazed by the number of interesting stories you can learn even about people you’ve been working with for years.

Some time ago, I got a very dysfunctional team. The team members were demotivated, frustrated; the environment was full of blaming and contempt—so thick you could feel it in the air. However, they were in a stage of not seeing reality, pretending that they were just fine. I agreed to run a short workshop with them and see what I could do to help them out. From that short retrospective, using Patrick Lencioni’s Five Dysfunctions of a Team concept, they reflected on the current state of the team and were able to see that it was actually very unhealthy. It was eye-opening. After the first moment of hesitation, when I told them no one could solve it for them and they needed to take responsibility for their environment and relationships, they started coming up with ideas. The conversation became very open but also surprisingly very constructive. We talked about building trust, the impact of positivity, and the need for strengthening relationships.

Long story short, the next day one of them, the most frustrated person from the team, came back and offered to organize some team building. He said he had already talked to several of his colleagues and they would go for it, and then he asked me to join. He thought we should start with an appreciation loop to raise the positivity. The following Friday, we went to the local pub, and before we had a few beers, we ran the appreciation loop. Everyone drew a name from a bowl, and the name you drew was the person you had to appreciate. If you got your own name, you had to change it. Simple and easy. Turned out, it went very well. It was amazing how a very simple event like going for a beer and spending some time talking to each other could make a difference. We ran several retrospectives after that, and they quickly became a well-functioning collaborative team.

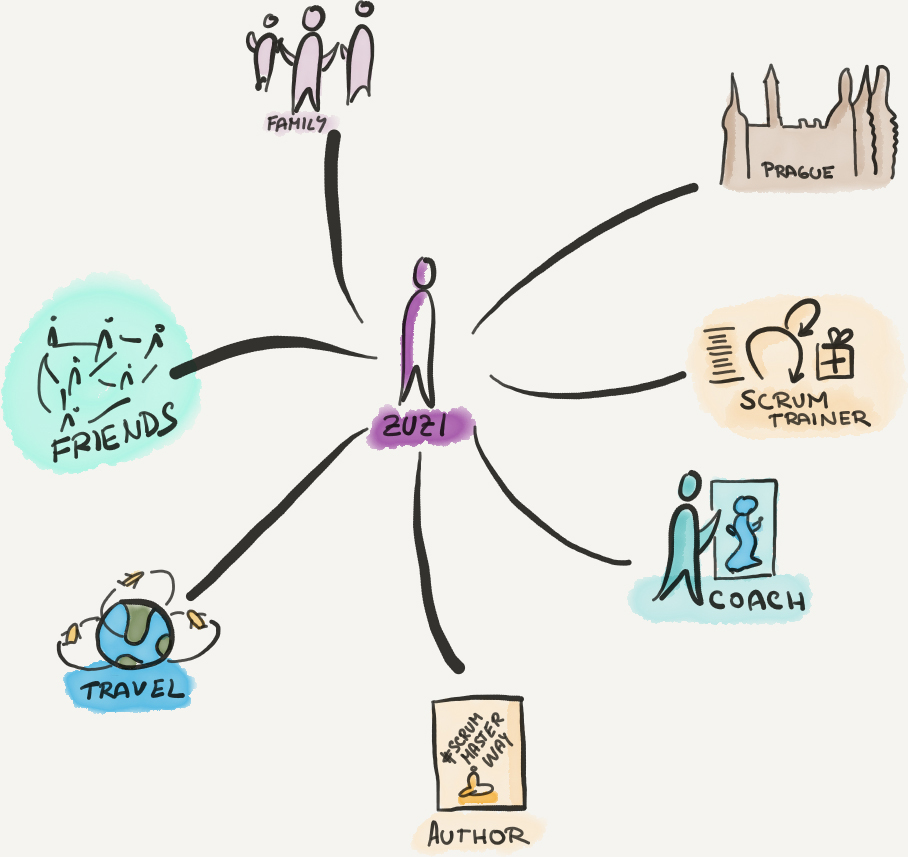

Personal Maps

Another interesting method for getting to know one another better is to draw a personal map [Mgmt19]: you draw your own mind map with your name in the center and add interesting categories about yourself, such as education, work, hobbies, family, and friends. You can add pictures to make it more fun. The more you think about yourself, the more you raise your own awareness about the decisions you’ve made and the events that have shaped who are you, and you help others to see that. Leaders need to build high emotional and social intelligence before they are able to see the group as a single integrated whole and trust it [CRR13], so personal maps are a great starting point.

How Are You Leading Your Life?

Michael K Sahota, CEC Certified Enterprise Coach and CAL Educator

A key part of being an effective agile leader is having healthy relationships. Powerful leaders are ready to look at the quality of relationships they have with others and how they are showing up in those relationships.

A pivotal change in my leadership came to me when I was going through a challenging period in my life. I was reading Breneé Brown’s book I Thought It Was Me,12 and there was a sentence that really grabbed me:

You can only be kind to others to the extent that you are kind to yourself.

It was a wake-up call in my life. I became very aware of my “internal critic” and the talk track of self-judgment that accompanied my perfectionist personality. I thought about the quote and I wondered: “How kind am I to my kids? To other people in my life?” At that moment, I set an intention for myself to be kind to myself and others. But how? I created a “simulation game” in my mind: An Epic Quest for Self-Kindness.13 The next two years took me on a life journey as I “leveled-up” in my quest for self-kindness. I ran experiment after experiment to try anything that might support the journey. I found the “weird stuff that works.” I started with meditation and experiential workshops. I then took a deep dive into personal growth by going to India, where intense psychological processes of clearing my mind initiated a permanent shift in my consciousness. This became my path to silence my mind and find peace and stillness among the stress of life. This opened my connections to self and others.

As I look back on my career, I can see how important this journey was in shaping my current ability to inspire and influence others.

It is important for you to find your own path of self-discovery.

The invitation is to consider, “How kind are you to yourself?” And perhaps set the intention to go on you own epic quest to create a powerful inner shift that not only will unlock you but will unlock all your relationships as well.

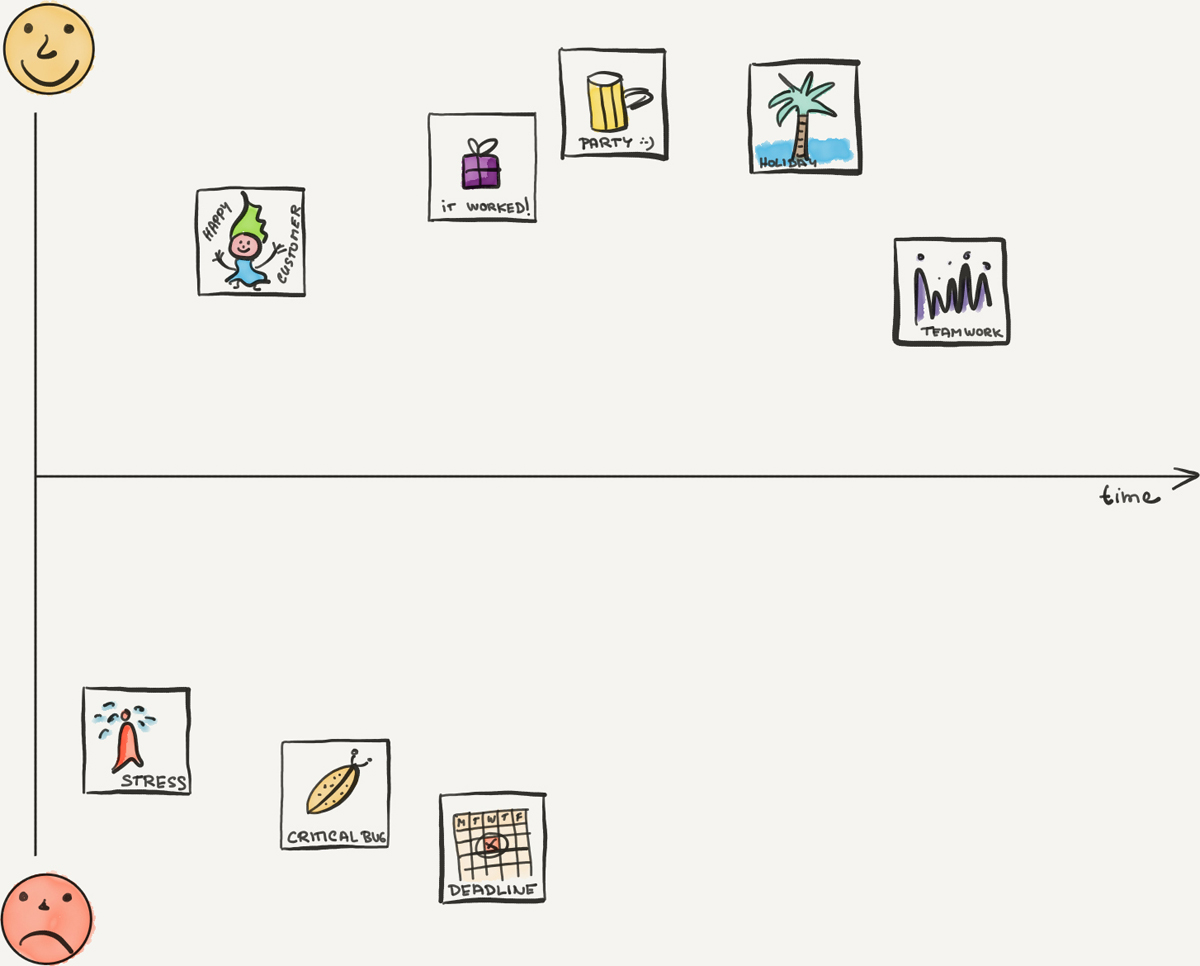

You can draw your own journey, visualizing important events and sketching them on your journey drawing. Some of them you will evaluate as more positive and put them closer to the smiling face. Other events you will see as less positive and therefore put them closer to the frowning face. In both cases, the visualization makes things easier to share with others, and the drawing makes it more fun. Overall, it increases the positivity, and people become more open in positive environments.

Assessment

If you wish to invest in a more structural approach to building trust, you can take the Table Group assessment,14 which shows you in a very simple graphic, based on the Teamwork Dysfunctions15 model [Lencioni11], how healthy you are as a team and recommends steps for improvement. Regarding absence of trust, the Table Group recommends one additional one step you may consider: using a personality assessment (e.g., MBTI,16 DiSC17) to help team members understand one another’s different preferences, patterns, and attitudes. Understanding people’s personality helps team members to be nonjudgmental and leverages the diverse approaches and perspectives of the team. Also, the second team dysfunction, fear of conflict, which deals with artificial harmony, is very often grounded in the absence of trust. To deal with this level, you can use another personality assessment, TKI,18 to help people understand how they deal with conflict together—which, combined with creating team agreements and acknowledging that conflict is neither good nor bad but just a voice of the system (as described in Chapter 5), grows the trust.

Teamwork

The most complicated shift for traditional managers working to become agile leaders is learning to deal with teams instead of individuals. An important part of your leadership competencies is collaboration. At the end of the day, in agile organizations, since the structure is flat, everyone is a member of some team and most likely of some community as well. That makes things easier, as everyone has experience with self-organized teams and with emergent leadership.

If you are not there yet, starting the communities or virtual teams on initiatives that will let them experience emergent leadership is a good first step. Also, even with a very traditional structure of departments and managers, you can look at the managers as a team. This is where agility at the organizational level often starts making all managers part of two teams—the one they are leading and one of their peer managers. While, for most of them, the team they are responsible for feels closer and more important, the opposite needs to happen: they need to feel a closer relationship with their peers than with their subordinates. They need to stop competing for power and influence and instead collaborate to achieve their common goal. Only then can they take a step back and become coaches and facilitators rather than decision makers and be closer to becoming agile leaders. The prerequisite for all teams is that they have one goal, which derives from the organizational purpose. Without team spirit, there is no agile. Every agile journey should start with defining strategic goals and forming teams around them.

One of the most interesting shifts I’ve seen from a traditional structure to a team-oriented structure happened not at the development team level but with the executive team. Originally, it was a bigger group of individuals who fought for power, number of people, and better space, blaming each other at every occasion, focusing on local optimization over the common goal. For example, the IT director was refusing to order computers before a new employee started working, the testing director always had his people busy on ongoing projects so they couldn’t help in cross-functional teams, and the operations director was trying to optimize the process for his assistant even if that meant hundreds of extra hours spent by other employees. When anyone in the organization had a creative idea that challenged the status quo, it was almost impossible to make it happen.

Once we reorganized into a flat agile structure, we also narrowed down the executive team to four directors and created a good team spirit, investing ourselves into trust and open communication. It was amazing how fast we were able to react to creative and innovative ideas, run experiments, try different ideas, and support each other. It was fun, it was energizing, and most important, it was working and bringing business results.

Building Communities

Agile organizations have their basis in self-organization. While the team structure makes the org chart less important, the communities take over and drive many initiatives that in the traditional world used to be centrally driven. The community is a free, inclusive, volunteer-based entity with a common goal to achieve. Once the goal is achieved, the community can be disbanded or can continue working toward another goal.

Organizations usually have different communities of practice19—an agile community, a community focused on better development practices, a community focused on increasing quality, a community focused on good design, a community focused on improving the architecture, a community for the customer segment, and so on. Anyone can start a community. Because everything is transparent, the idea is that the community is vetted by the rest of the organization, and if no one joins, it’s a signal that the issue is not interesting enough for others to spend their time working on it. If people are interested and find regular time to meet and work on the task, it’s a signal of its importance to the organization.

Nowadays, communities can also be active online, over Slack or social media, especially if you create a community that extends beyond the organizational boundaries. Agile organizations are built on the enthusiasm and energy of communities. They share the way they work with others, they collaborate with external parties in wider networks, and they sometimes even do most of their business through volunteer work. You don’t have to rely on traditional employees. Modern organizations build networks of supporting teams that are aligned around the same purpose. Traditional organizations with employees is only one way of working. Engaging communities is in some cases a more powerful way of achieving the common vision.

Leaders Ask for Help

Evan Leybourn, Founder of Business Agility Institute

I never set out to create a community or research organization. It was never part of my career path or what I trained for. And yet, when the opportunity arose, there was no other decision I could make. Hence, the first question I had to ask myself was, What does it take to be a leader in this role?

No one could answer this question for me. And no one can answer this question for you either. While there is plenty of advice and there are plenty of role models to follow, the delta between who you are and what you need to be is uniquely your own. I had to be honest about my own weaknesses—those skill limitations and cognitive biases that could easily destroy the Business Agility Institute before it had a chance to grow. In my case, I put aside my ego and arrogance and asked for help. A lot of it.

I realized that I needed more than just staff. I needed thought leaders, experts, and practitioners to join us. People who, like me, could put aside their ego and share their insights and experiences. Not for money or self-promotion, but in service of a common-vision.

The first part of this, and possibly the hardest, was to communicate the vision. This is fundamentally important no matter what organization you are in. Why do you exist? How do you make the future better? And why should anyone else care? It’s that last question that many organizations struggle with. They spend so much time looking inward that they assume that everyone sees the world through the same eyes. We needed to clearly articulate why our vision was important—not just to us but to you.

But a vision without action is worthless. We needed people. And this was the biggest lesson for me personally. People want to help as long as it’s not a transaction. People are naturally curious, sharing, and giving. But we had to make it easy for them to join us. Every step between you and them is a barrier. So we made everything as clear as possible. We made it easy to start a local community. We opened the Library to everyone. And we designed clear approaches to our research so volunteers understood the time and effort involved.

And it has been more successful than I could have possibly imagined. Today, we have more than 150 volunteers. They run our local Business Agility Meetups, organize global conferences, write case studies and references, take stewardship of the Business Agility Library, and undertake leading research on the future of business.

Books to Read

The Five Dysfunctions of a Team: A Leadership Fable, Patrick Lencionis (Luzern, Switzerland: GetAbstract, 2017).

The OpenSpace Agility Handbook: The User’s Guide, Daniel Mezick, Mark Sheffield, Deborah Pontes, Harold Shinsato, Louise Kold-Taylor (New Technology Solutions, 2015).

In a Nutshell

Trust is the prerequisite for a well-functioning team.

Radical transparency is the key enabler of agility.

Agile organizations are built on the enthusiasm and energy of communities.

Modern organizations build networks of supporting teams that are aligned around the same purpose.

1 Product Backlog refinement is where Product Backlog is created and ordered in Scrum.

2 Agile Lean Europe (ALE) is a network for collaboration of agile and lean thinkers and activists across Europe: http://alenetwork.eu.

3 Video from ALE Network Europe StrategicPlay Vision, XP2011, Madrid, Spain: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zg2PMv8lFUA.

4 StrategicPlay: http://strategicplay.de.

5 I’ve been using mentimeter.com or pollev.com, but there are hundreds of similar tools.

6 Dodo Pizza Story: https://dodopizzastory.com.

7 Buffer Transparency Dashboard: https://buffer.com/transparency%20.

8 Zappos Insights: https://www.zapposinsights.com/tours.

9 Menlo Innovations: https://menloinnovations.com/tours-and-workshops/factory-tours.

10 Five Why is a root-cause analysis technique in which you ask why five times to help you understand the issue better.

11 Escape the Room game: https://escapetheroom.com.

12 Breneé Brown, I Thought It Was Just Me (But It Isn’t): Making the Journey from “What Will People Think?” to “I Am Enough.” New York: Brilliance Audio, 2014.

13 Inspired by Jane McGonigal’s SuperBetter story. For more information, visit https://www.superbetter.com/about.

14 The Table Group provides team assessments based on The Five Dysfunctions of a Team [Lencioni11]: https://www.tablegroup.com.

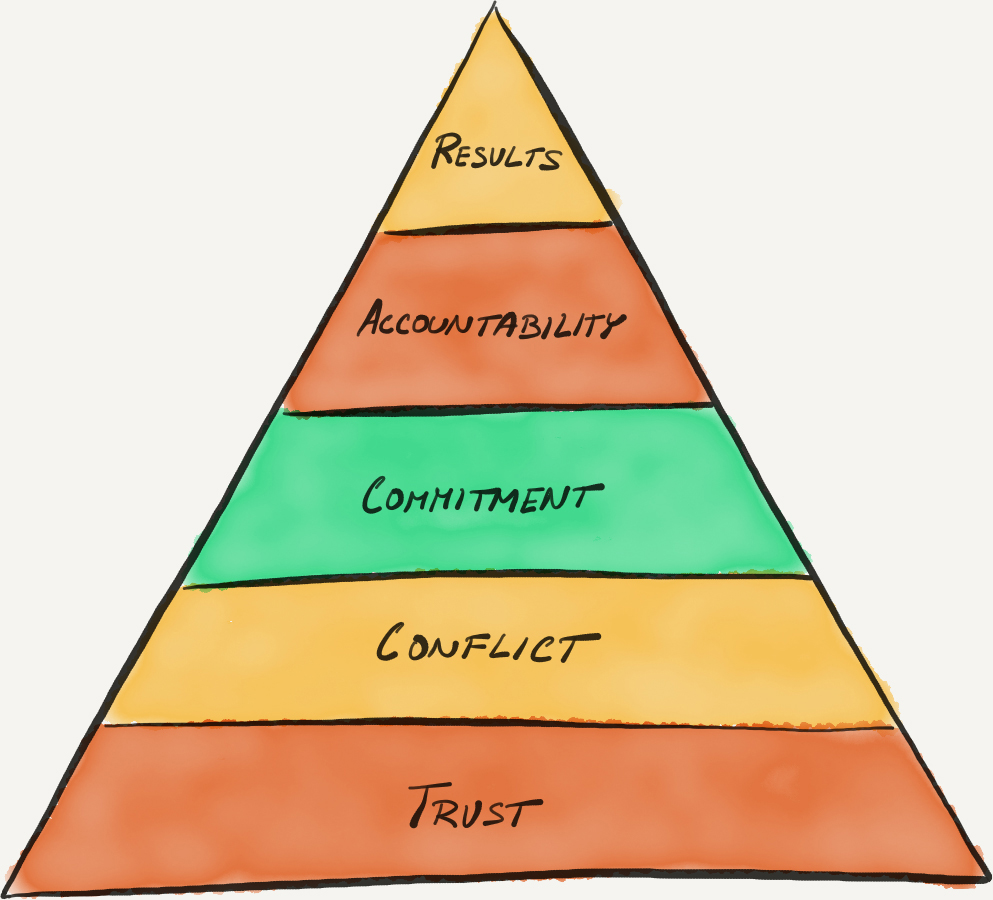

15 The five team dysfunctions are absence of trust, fear of conflict, lack of commitment, avoidance of accountability, and inattention to results.

16 MBTI is the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, a personality type assessment: https://www.myersbriggs.org.

17 DiSC (Dominance, influence, Steadiness, Conscientiousness) is a personality test: https://www.onlinediscprofile.com.

18 TKI is the Thomas-Kilman Instrument, which assesses conflict mode: https://kilmanndiagnostics.com/overview-thomas-kilmann-conflict-mode-instrument-tki.

19 A community of practice is a group of professionals who share the same interests in resolving an issue, improving skills, and learning from each other’s experiences.