8. Building an Agile Organization

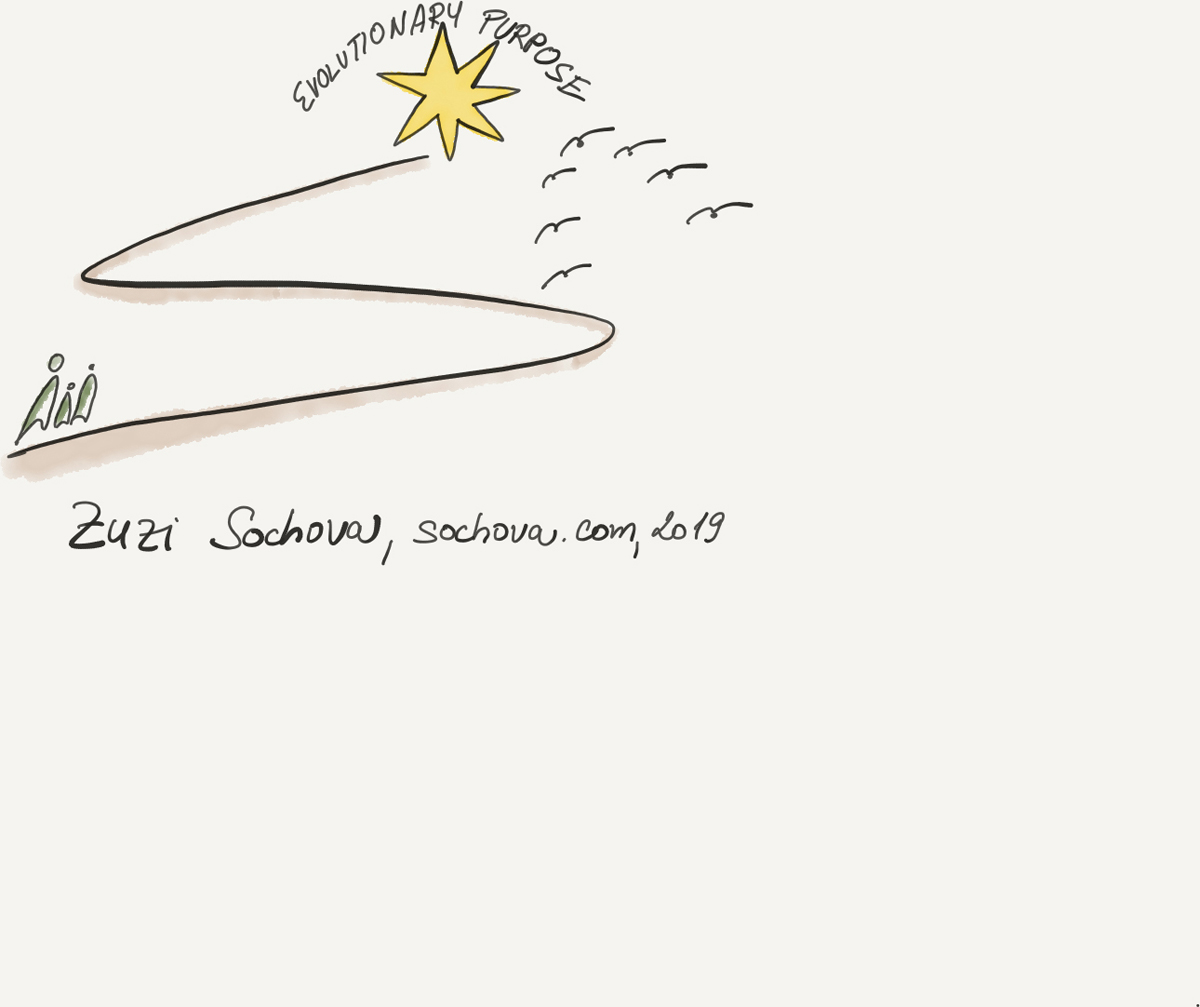

Once they have embraced agility and a new leadership style, agile leaders naturally help the organization to embrace the same values and principles. An agile organization is agile to begin with. There is no specific framework needed to make an organization agile: all you need is to practice the agility at all organizational levels. Experiment and, through frequent feedback, find your own way of doing things. You can never be finished in that effort, as there is always a better way of doing things. It’s like a star on the horizon—you can never touch it, but step by step, in short iterations, you can get closer.

The agile organization is like a star on the horizon—you can never reach it, but you can come closer, step by step.

All you need to bring along is courage, commitment, focus, openness, and respect.1 “Being agile” is not the same as “doing agile.” The frameworks, methods, and practices are just tools that can make the journey faster, more enjoyable, and more efficient, but the tools alone will not change the mindset. Nonetheless, there are some concepts that will help you to understand how to be successful in building an agile organization.

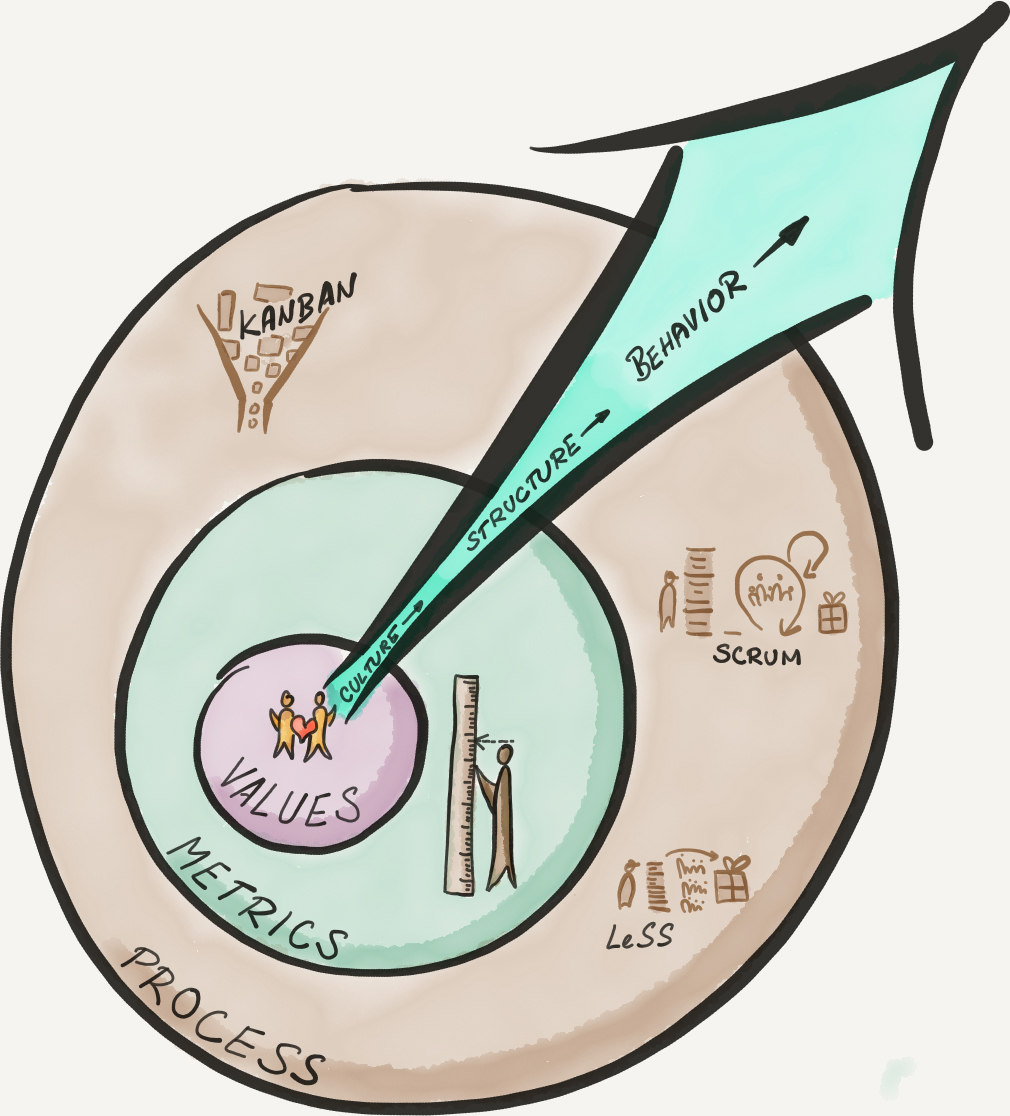

Inside Out

Most agile transformations start from the outside in, as a process or structural change where management pushes a new framework to the organization but without real values or culture change. It looks like a good start, as it is simple and practical. However, it usually results in just doing agile, not being agile. The expected organizational success is not any closer, and all you get is “fake agile” and “Dark Scrum” [Jeffries16] implementing practices without any meaning.

Any sustainable change needs to start from the inside out, with a change in values.

If you care for sustainable agility, the only way to achieve it is to go from the inside out—start changing the values, and build that shift of the mindset from the inside. Do we care about learning through experiments, team collaboration, value delivery, and responding to changes? Do we live according to those values? That’s where we need to start. Without changing those values, no frameworks will help us.

The most common reason for failure that I see in the organizations implementing agile is having agile as another process and a goal by itself, which almost never works. It usually starts with the same request: “We need to train X number of people in agile.” And when everybody is trained, the “agile transformation” is done. Simple and straightforward. But there is no change of structure, culture, or values, nor is there any clear expectation of the outcome. I have been in many organizations that approach agile in this way, and I learned that this shortcut never works.

Let’s look at one failure story as an example. Once, I was asked to facilitate an introduction to agile and Scrum training in a very small software organization. Those are usually easy to switch to the agile way of working, as they tend to be flexible and collaborative. In the beginning, we were talking with one particular team—it seemed quite simple. The participants were curious and interested in the content, the managing director and his management seemed supportive. However, one warning that this was not going to be a smooth transition came as we were finishing on day one of the two-day introduction, and the group mentioned that they were not done yet—they still had to finish their work planned for that day. They worked until midnight both days. They all repeatedly agreed that staying late to meet a rigid quota was an exception to the norm and that they should have more time in two weeks when the project was delivered. We always offer ongoing coaching support, but they were positive they didn’t need anyone.

In roughly six months, we were called back for a one-day review, and it became clear that the organization hadn’t changed much except for holding a few unproductive meetings. The team members were still assigned individual tasks and were still too busy. It didn’t take me long to figure out that they hadn’t stopped even for a few hours to discuss how they were going to change the way they worked. The only change that had happened was in terminology, and not surprisingly, that change was not enough to get any result. We talked about the need to start from the inside out with the team and management, but unfortunately, the same thing happened—only this time, the organization added more processes and hired an inexperienced ScrumMaster to implement Scrum. As before, the organization refused any agile coaching, as agile was now clear to all concerned, and they were fine. It was no surprise that eight months later, I was there again, this time to train new team members because many people had left. Their ScrumMaster was completely burned out, due to leave at the end of the month as well. This time, everyone was ready to listen and change their way of working. We did a one-day workshop after the training in order to start changes. They also articulated a strong strategic reason for the change and eventually managed to give the team time and support to change the way they work. This time, the change started from the inside and moved outward. It was harder than the previous terminology and process changes, but it worked out and paid off.

List at least three strategic reasons for the change to agile:

Which values need to change first in your organization for it to become agile?

How do you know you are getting there?

What processes, practices, or frameworks can help you to achieve agile?

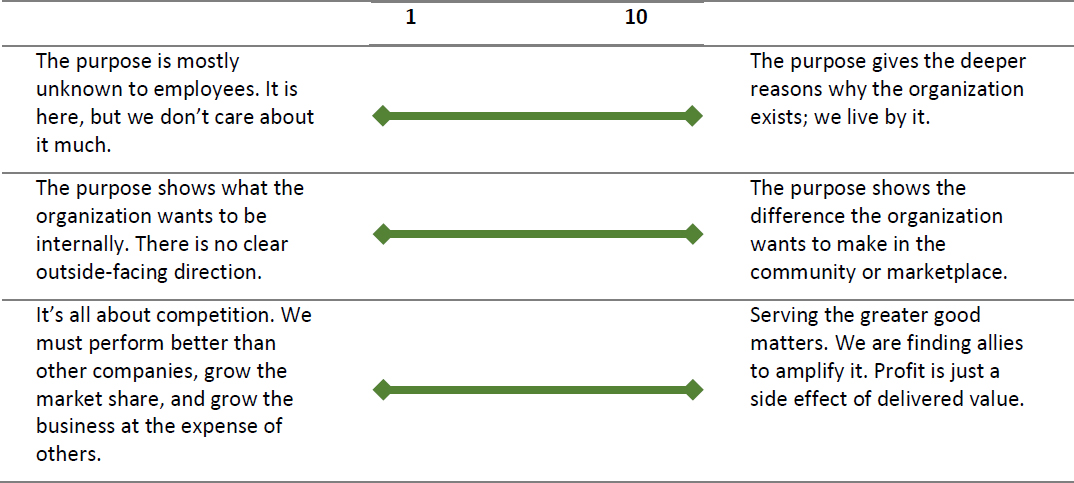

Evolutionary Purpose

The more self-organized and decentralized the organization, the higher the need for a strong and clear purpose, so that the people will show up for the all-important reason that they believe in it. Startups are usually driven by such evolutionary purpose. A good evolutionary purpose shows the direction, gives people the goal, and is unifying. It defines who are we and who are we not. “The evolutionary purpose reflects the deeper reason the organization exists. It relates to the difference it wants to make in the community it operates in, as well as in the marketplace it serves. It is not concerned with the competition or outperforming others; it is serving the ‘greater good’ that matters” [Reinvent_nd].

For traditional organizations, such a purpose is very distant and hard to imagine. They live in a world of hard metrics, goals, and objectives. They live in a world where employees need to be told what to do and measured accordingly (theory X). With a good evolutionary purpose, the world becomes a place where people are naturally motivated (theory Y) and aligned by the purpose—all you need to do is give them autonomy and trust that they are going to make it.

What is the purpose of your organization?

Which of the following statements best describes your organizational purpose?

The farther on the right you are, the higher evolutionary purpose your organization has.

The evolutionary purpose is a prerequisite for an agile organization. Without it, full autonomy will create chaos. If the previous exercise didn’t show a strong enough purpose, don’t worry. Agile organizations don’t become agile overnight. Having a good purpose is an evolutionary effort. It will happen eventually, and usually much sooner than you might have expected.

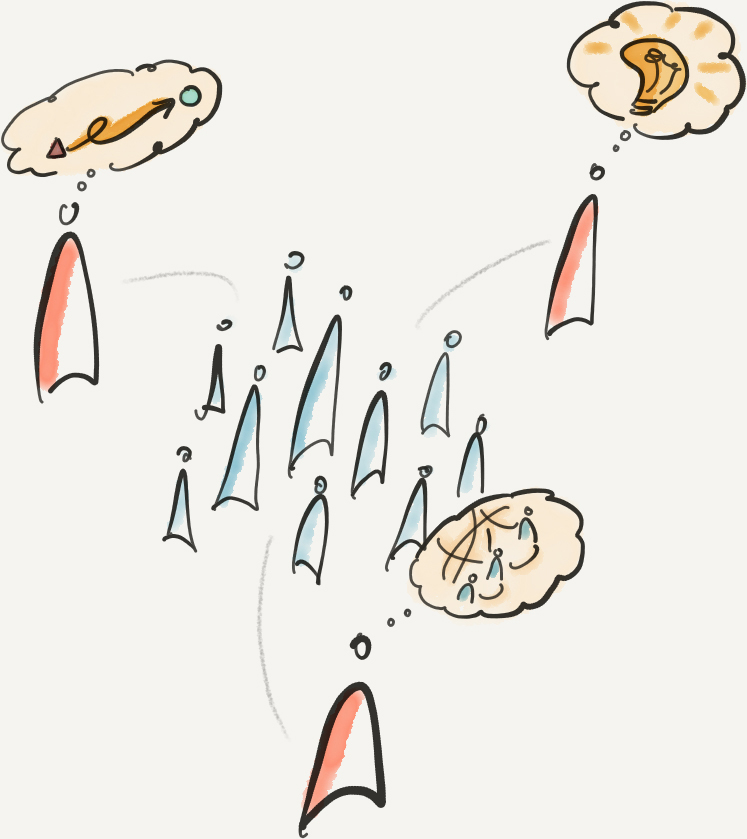

Emergent Leadership

Unlike in traditional organizations, where leadership was mostly positional, in agile organizations we rely more on emergent leadership. In other words, anyone can become a leader if he or she has a strong enough idea and courage to take ownership and go for it. Emergent leadership is the key driving force for any self-organized environment. In a well-functioning agile organization, leadership is spread around and decentralized. Leadership is no longer linked to any position, it’s accessible to the teams and to individuals, who are free to create any teams around their ideas. Everyone can become a leader. It’s your own choice, as long as you’re ready to take responsibility and ownership.

The core prerequisites for emergent leadership are radical transparency and frequent feedback—nothing that wouldn’t have been in the agile environments already. Anyone can come up with an idea, share it with everybody and ask for feedback, while the people around them make sure the idea is worth following. In the beginning, you can start with a small initiative. Later the initiatives may grow and become wider. What makes it a game changer is that the leaders don’t necessarily report to any manager but to their colleagues, and to some extent to the entire organization. The leadership is emergent. What doesn’t make sense in a traditional organization starts to make sense at a small scale, at the level of self-organizing teams, and thrives in flat agile organizational structures.

Emergent leadership is a concept that may be hard to understand, so let’s take a look at what Google has to say about the topic, since Google made emergent leadership one of its key principles: “One thing we look for is general cognitive ability, the second is leadership—in particular, emergent leadership as opposed to traditional leadership. Traditional leadership is, were you president of the chess club? Were you vice president of sales? How quickly did you get there? We don’t care. What we care about is, when faced with a problem and you’re a member of a team, do you, at the appropriate time, step in and lead. And just as critically, do you step back and stop leading, do you let someone else? Because what’s critical to be an effective leader in this environment is you have to be willing to relinquish power” [Friedman14].

It makes sense when you read it; however, that doesn’t mean it’s easy to apply. We are all fighting here with the social and cultural heritage of decades of hierarchical, positional leadership. Only in recent years have we started to hear about companies where emergent leadership has become a core driving force for their success. This reflects the fact that industry has needed to deal with VUCA challenges only in the past few decades. Complexity needs to be addressed by complexity, and emergent leadership is one of the concepts that allows organizations to be more creative and innovative and to better deal with complexity.

Team Forming in a Corporate Environment

Ondrej Benes, Head of Deutsche Telekom IT, Czech Republic

Our international telco corporation was undergoing massive transformation toward becoming an agile organization. Some parts had been using agile for ages, other parts had just started or were about to start sooner or later. We opened the discussion about how to approach forming our future agile teams within the organization. Pretty quickly, we came to the conclusion that we would do an experiment: let our colleagues form teams themselves. What we laid down were some conditions to be met by the to-be-created teams (maximum number of people in a team, that a team needs to be cross-functional and able to handle the whole lifecycle from analysis to operations, etc.).

And we did not stop there. We decided to go yet deeper in terms of democratic team forming and let the newly established teams select their ScrumMasters. Also, it was up to Product Owners and these teams to agree on who would perform the Product Owner role toward which teams. We all were very, very curious what was going to happen. There was no emergency break in terms of sponsor final veto or management right to overrule, so we had no idea of all the paths it may take us on, but we trusted the system to behave with the best intentions.

One day, we met with the team in an offsite session. Participation was on a voluntary basis. Those who decided not to come had prepared their avatar and delegated their vote to someone in attendance. After some initial hesitation, physical moving around started—we could observe how people were grouping with others, how names were being added or crossed out on team flipcharts representing team rosters. The intensity increased as we approached the time limit. Then a feedback round via thumb up/thumb down sign told us whether we were satisfied with the result or another round was needed. Once teams were created, we jointly reviewed all upfront submitted nominations (ScrumMaster, Product Owners, etc.), modified the list on the basis of ideas from those present, and proceeded further with selection. Within half a day, the teams forming, and the other roles voting experiment was completed in real-time, face to face, and transparently involving anybody who decided to participate.

This activity may not sound very dramatic to born-agile startup organizations and in fact may sound like a common sense thing to do, but in the context of our huge international—and, at that point in time, still very hierarchical—corporation, it was at least a bit unusual.

We were glad that we were brave enough to put the program-level roles into the game as well. I still believe that this was a good message for the team. In my view, it was a demonstration of not just spoken but lived transparency, empowerment, and shared leadership. There were certainly also lessons learned about what to do differently next time—one example could be to have given qualification criteria when gathering nominations for roles such as ScrumMaster and Product Owner. We may have been too “liberal” in that the nomination was open to anyone who showed interest in the role and had the ability to convince the team to accept him or her. This may not have been the best approach, as you need to carefully consider here the overall maturity of the environment. It turned out later that the system of self-regulation failed in some regards, and the teams often selected a candidate they knew while knowingly compromise on some qualities rather than choosing somebody they did not know but who might have had higher potential. Yet another confirmation of the fact that human beings naturally tend to avoid the unknown (survival instinct).

If I were faced with the same situation, I would do a similar exercise again. I believe such team forming is the right way to invite everybody who wants to steer things, to influence the environment we work in. It supports engagement and emergent shared leadership.

Culture

As Edgar Schein said in one of his books, “The only thing of real importance that leaders do is to create and manage culture. If you do not manage culture, it manages you, and you may not even be aware of the extent to which this is happening” [Schein17]. And yet, many leaders are still focusing on the processes and frameworks, avoiding the topic of culture. I can understand that, as it took me a while as well. Culture is intangible. It’s hard to touch. Hard to define, hard to measure. However, it is a critical piece of organizational success. Culture reflects our values and philosophy, the way we are. Being agile is about changing the mindset. If enough people change their mindset, the culture changes, and the organization becomes an agile organization. Simple if you say it this way, hard to make it happen.

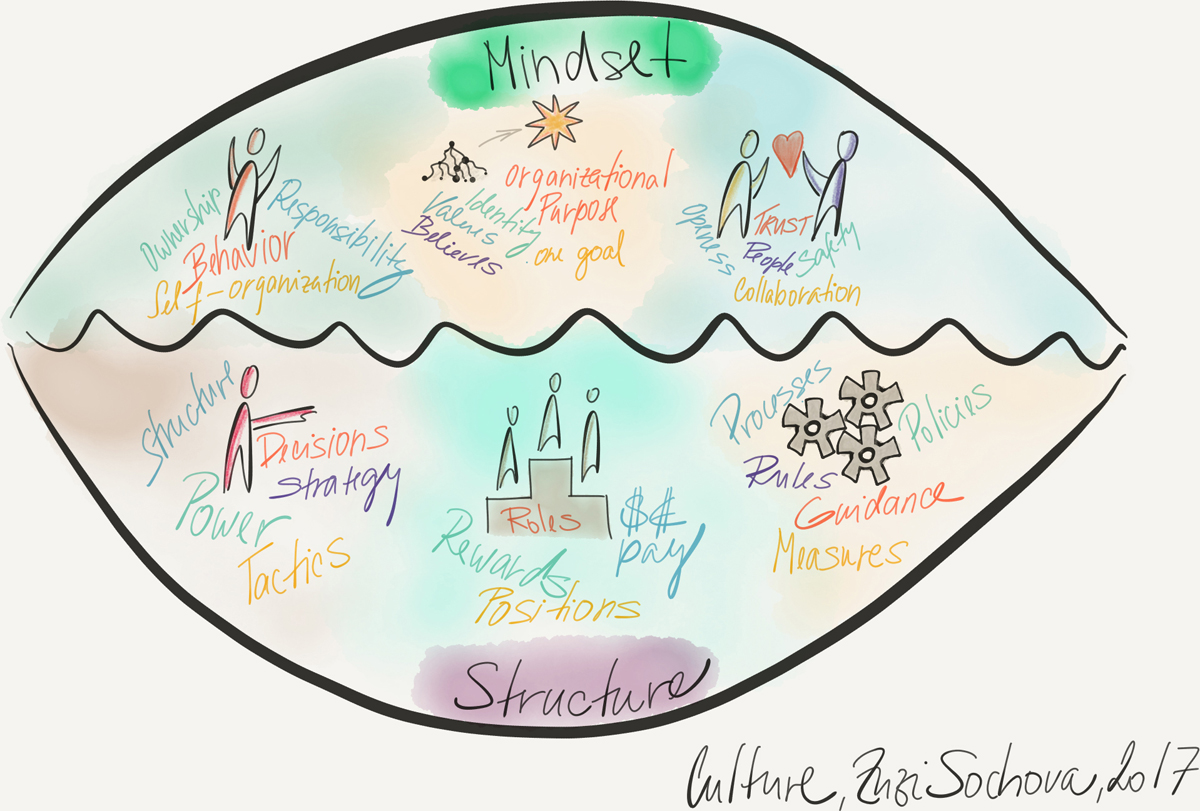

Culture is like a clam. It consists of two parts—mindset and structure—which are connected. You can’t separate them from each other. If you do that, the culture dies and the organization will struggle. Similarly, like a clam, those two parts will open farther from each other to accommodate a change, then close when the structure meets the mindset, which creates positive energy and readiness for another change. We may debate whether the mindset follows the structure or vice versa, but I don’t think it is important. It’s all about the right balance. It’s about being aware of both halves and not sacrificing one for the other.

Changing the mindset is harder, but it brings long-term results. Start with a purpose in mind. Come up with a purpose strong enough that it makes you get out of the bed every morning and put some energy into achieving it. Something you truly believe in and are willing to take ownership of and responsibility for. Something that makes you collaborate with other people, something that makes your day. When you succeed with the mindset shift, it will create pressure on the existing structure, and you get the energy to change the structure.

On the other hand, sometimes the only way to accommodate a change is through changing the existing structure—for example, from component to cross-functional teams. No mindset will grow if the structure is too tight.

Too Tight a Structure Kills the Mindset

I remember helping an organization where the mindset was killed by a fixed structure that created no space for people to even breathe. The company went through the basic agile and Scrum training for teams, but already during the training there was one indicator that it was going to be hard.

Any conversation about cross-functionality, collaboration, learning, or refactoring ended with the team saying they had no time. When we touched upon the metrics the first day, I mentioned just as a joke that they could measure how many lines of code were written by each developer per day. People usually laugh when I say that, but this time, I got this weird look instead. “That’s what we have,” they said. “No one will help anyone, as they might not create enough code themselves,” they continued. It turned out their pay was based on that metric. New people were leaving because they didn’t have enough work they could do without help, and as no one would help them, they couldn’t learn fast enough. As a result, they couldn’t reach a reasonable salary quickly enough. When I asked how they dealt with this problem, they said that was the reason they were at the training. They felt they needed a change. They had partially started ignoring the metrics and collaborating more.

This example is one of the weirdest ones. This team had micromanaged individual processes, focused on maximizing individual efficiency, and made everyone highly competitive no matter whether the value was there. Their director was often canceling the team’s vacation plans at the last minute because they needed to work more or needed to finish something over the weekend. You might ask why the team members didn’t leave. I guess they got paid after all, and in that region, there was not much work. They kept getting promises that with the next project it was going to be better. But it never was.

Unfortunately, the organization was unable to shift the mindset. It failed to create any Scrum development teams or even have frequent retrospectives. There was no discussion about the scope or priorities, as “everything” had to be done. In the end, the employees asked me if I would be willing to talk to their bosses. Sure, anytime. However, it never happened. The management didn’t care. They were purely in the achiever mindset, believing that their employees needed the pressure to do any work (theory X), and the organizational design, which was highly hierarchical, was not about to change either, because the managers would take any delegation as a threat to their position.

Unfortunately, there are no magic pills for such organizations. Sorry about that. Some environments are just not ready yet. Agility needs a sense of urgency (which in this case was not there yet) and certain readiness at the management level (not even close), or enough space in the structural part of the culture so the mindset can grow within (not there either). Any agile attempt will fail unless the structure changes a bit to create the space and opportunities for a new mindset.

If you want to change such an environment, agile leadership will help. Look at the organization from the system perspective, applying the agile leadership model and acknowledging that what is described in the scenario is neither wrong nor right. Reading it only gives you one perspective. Stay a bit more on the listening side and get awareness by proactively searching for different perspectives. A common understanding is key, and transparency is always a great help. Then, once you manage to let it go and embrace it as is, the third step of act upon will show you very different opportunities than if you just take sides trying to decide what is right and wrong.

One possibility of how to act upon is to do the previously mentioned force field analysis. It’s clear that the forces for and against adopting the agile mindset were not balanced in that organization, not even close; however, the tool helps you to identify where the teams should focus in order to get it into balance and shift forces toward the agile side of the scale.

Another way to approach this from the act-upon stage is to visualize the power or the collaboration and show the results from the different ways of working. When everyone on the team feels that the current state brings too much pressure, they might feel a sense of urgency already. In the preceding scenario, they’d been doing it partially already, and sometimes all that is needed is to have the courage to overcome the first obstacles and not give up. Just keep going.

However, there are so many other options to choose from, so don’t overanalyze it. Just give it a try, spin the wheel a bit more, and see what the get-awareness step would bring you. Don’t create plans for the future—just stay in the moment.

Too Open a Structure Can Create Chaos

If you open the structure too much while the mindset is not yet firmly in place, all you get is chaos and the failure of otherwise well-working practices. For example, one organization I worked with was going from a hierarchical management that made all decisions without much delegation into very advanced agile practices. The management was struggling to let go. From their traditional mindset, managers didn’t even see the different delegation steps. They either decided themselves or let go. For them, it was a black-and-white world. One day, they decided that because they were agile, meaning they had implemented Scrum at the team level, they should delegate the decisions about Product Owner bonuses to the Product Owners team. The problem was that this group of Product Owners was far from being a team, and even worse, the members had different goals and were competing for success. They had no common goal, as the organizational vision was quite abstract and didn’t work as a unifying evolutionary purpose. Because individual relationships were very weak, it was a pretty toxic environment where blaming and contempt were part of the day-to-day life.

The freedom to decide on the bonuses is a great practice for well-functioning teams, but here, it only led to a huge fight. The conflict hidden behind the curtain of artificial harmony fired up and was stronger than ever. It was ugly, creating frustration among both Product Owners and management, because there was no clear right or wrong solution.

It gave some feedback to the management, reminding them that teams need to be taken care of, that they are different from a group of individuals, and that to make a team of these employees, management needed to create a team environment. I also gave feedback to the team, showing them honestly where they were. The first few weeks and the early retrospectives were hard, but in the long term, the retrospectives led to more honest and candid feedback and helped the Product Owners to form a better team. Some of the issues they had pretended didn’t exist surfaced and were improved—even some things completely unrelated to the current situation. So, who knows what is right and what is not? In a complex system, no evaluation is helpful. Just get awareness, embrace it, and act upon it.

Having a strong purpose, values, and identity are the key to an agile culture. Otherwise, the organization is held together only by artificial rules, regulations, and processes. And when you take away the rules, regulations, and processes, people suddenly don’t know what to do, and they end up having individual fights. In a traditional organization, when there is no order or process to follow, very little work gets done. In an agile organization, the direction is defined by the organizational purpose, and the “how” is determined by the values and identity, so things happen naturally even without a push.

The Balance between Mindset and Structure

This example is from a midsize company that let the agile culture grow step by step. Several years ago, the company started with a mindset change. It took one project and tried Scrum at the team level. When I talked to the management, it was clear they had approved the Scrum experiment because the experiment was project-limited and because it tended to be a people-oriented company, management disliked saying no to employees. However, any discussion about self-organization ended immediately, as it created fear of losing control.

At every step, the organization had seen this project as different, weird, awkward, and, perhaps to the surprise of management, successful. Managers started adopting the Scrum terminology and accepting the ScrumMaster role. You could see there was not much happening outside of the project team, but the team members completely turned around the way they worked, and the results were almost instant: better quality, higher motivation, more creativity, and higher value delivered.

The results of this experiment—the one project—were so appealing that eventually one of the managers from a different division tried it with one of her teams. And then, step by step, the mindset part of the culture was on the move, and new teams were picking up and joining. In some teams, there was a structural change needed to allow cross-functionality and close business relationships, while other teams became cross-functional without many structural changes. Eventually, the organization was ready for scaling up. It combined a couple of fragmented projects into broader, business value–driven, customer-centric products under one Product Owner, and the management started to talk about agile leadership, team collaboration, and the agile culture. Then a new CEO was chosen who initiated changes in HR, finance, and the overall way the organization worked, so it became team-oriented, collaborative, and culture-driven.

The entire journey was neither smooth nor short. We are talking about an organization of several hundred people changing over a period of almost a decade from a very traditional mindset, individual-focused structure, and expert leadership into a quite agile organization focused on the value streams, with team collaboration hardcoded in their DNA, and significant presence of agile leadership. However, at every step, they looked into the balance between structure and mindset and used frequent feedback loops to correct the deviances when one part was too far from another. Did they do it perfectly? Not even close, but they made huge progress on their agile journey, which brought tangible and measurable positive outcomes to their business.

An iterative approach whereby you run small experiments and learn through frequent feedback loops is a good way to start the agile journey. There is no right or wrong way to change an organization, and often you won’t know the impact of an action until you try it. The company in the preceding example tried many things, often needing to step back, regroup, and give the other half of the culture time to catch up. For agile leaders, the hardest meta-skill is patience. Being patient is the key differentiator between the Achiever and the Catalyst leadership styles. It’s the difference between being immediate result oriented and being focused on long-term goals. The culture shift can’t be pushed; the right culture needs to grow.

The culture shift can’t be pushed; the right culture needs to grow.

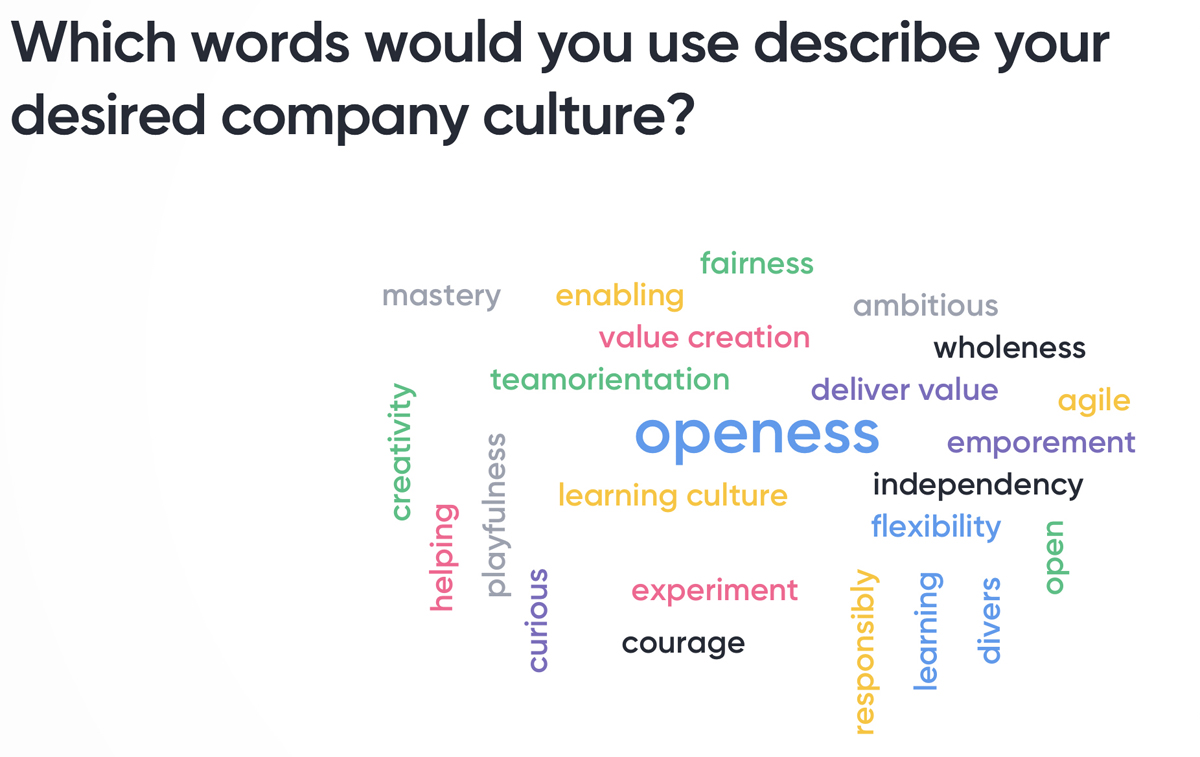

What words would you use to describe your current company culture?

What words would you use to describe your desired company culture?

Compare the two lists and think about what actions you can take to support the shift toward the desired state.

The preceding exercise is usually done in organizations as a workshop. You can use Post-it Notes and dot-voting, or go digital and leverage some online survey and voting tools that make the data-gathering phase much easier, faster, and transparent even for large groups. See Chapter 11 for more tips.

Example of Desired Company Culture assessment results

In my work, most of the time I focus on mindset change, as it has the potential to create the right balance of forces for the change, supporting a change in the structure of the organization. Start with small steps: little by little, start doing things a different way: collaborate; increase transparency, flexibility, and adaptability; and consistently share success stories. Let everyone see the impact, let the organization feel its own experience with agility. You can publish success stories in the internal magazine, organize regular agile meetups, write blogs, create live Facebook videos—no channel is better than the other. Every channel will catch its audience’s attention and interest. Don’t be too frustrated by processes and guidelines. As the mindset develops and the higher transparency makes things clearer and more tangible, the organization will realize that the current structure is preventing you from accomplishing the desired change, and the entire culture will shift. The culture clam closes up—the mindset and structure parts meet and start a new cycle of moving away from each other, waiting for another change to accommodate.

The good news is that when a mindset receptive to change is achieved, then changing the structure is relatively easy. But it’s a never-ending process, a continuous culture ping-pong of mindset, structure, mindset, structure, mindset, structure. . . .

The Power of Culture

Debra Pearce-McCall, Owner and Founder, Prosilient Minds

When I got promoted and made the big decision to move my family cross-country, I never expected the position to last only two years—and teach me a lifetime of lessons in agile leadership. The stakes were high; our focus was our customers’ health, well-being, and sometimes even lives. Our corporation measured our performance in everything from seconds (e.g., how long until the telephones are answered?) to cents (rate per covered person per month) to significant health outcomes, to the challenging duo of utilization rates (keep them low) and customer satisfaction ratings (90% or higher). We performed well, but when our contract came up for renewal, the other party decided to take it all in-house instead of outsourcing again. My next big decision was opting for transparency and figuring out how to best inform everyone on staff that we were going out of business—but not until after another year of providing the same levels of service (those life-impacting stakes weren’t going away!). My agile intuition to be honest, inclusive, and experimental held up over the next year: we would stay in business, it just would not be business as usual.

Years of experience in psychology and human systems, studying and working with our minds, relating patterns, and the processes of change, had already served me well as a leader. I knew the importance of psychological safety, clear communication, repairing misunderstandings, and other “soft skills” and could integrate those with budgets and meeting agendas, tough decisions, and performance standards. I could be very present, adaptable, and creative, and I encouraged that in everyone around me. This challenge was clear: What changes would motivate folks to remain in these disappearing jobs? In a lovely upward spiral, the numerous agile initiatives I created over that year kept everyone engaged and committed, which then gave me leverage to use when negotiating our severance packages (to be received only if we stayed until the end). Of several, here’s one fun example: Too far from “headquarters” to ship back our office equipment, I offered an alternative. We held our own “special sale” where employees bought office furnishing and supplies at amazing discounts, and we then used the money to have a fabulous finale party with families invited. And here is one career transforming example: I developed a program where anyone who was qualified and interested could be cross-trained (e.g., healthcare providers in our clinic could learn care management or utilization review; intake coordinators could learn billing and claims management, and vice versa). Almost every employee took advantage of these opportunities, which contributed to our 100% retention and to how easily folks acquired jobs after we closed. At the end of that final year of unusual business, we even achieved every performance measure, while doing all we could to ensure a smooth transition to the new operation, for all of our customers. In the decades since, I’ve coached leaders in all kinds of industries and situations, witnessing the power of the same keys I learned to apply that year: life means change and adapting, so open to it with curiosity; be real, as it’s a waste of energy not to be; communicate clearly; cocreate whenever possible; intend kindness and inclusion—and much of the rest will take care of itself, often in ways we may not be able to predict!

“We” Culture

An agile organization needs the right culture. At the end of the day, it’s all about collaboration: how we work as a team, support each other, and take over the responsibility and ownership for the team. Agile leaders need to create such a culture because, without it, agile can never be successful.

Tribal Leadership: Leveraging Natural Groups to Build a Thriving Organization summarizes the journey the majority of people in the organization need to go through. A tribe, according to the book, is quite a natural formation of people. “Birds flock, fish school, people ‘tribe’” [Logan11]. In any organization, you can find different kinds of tribes.

The first one Logan describes is “Life Sucks.” The good news is that these tribes are not common; only 2 percent of organizations are likely to be dominated by a Life Sucks tribe. We are talking about prisons, mafias, street gangs. They don’t understand how you can be happy about anything. Their mindset is “Life sucks. And you just don’t get it: there is no light at the end of the tunnel, no hope that it will ever get better.”

If you experience this type of tribal leadership at your organization, be patient. Approaching them with a shiny “Teams are great!” is probably unhelpful, and if you talk to them about moving to agile, you might as well talk about moving to Mars.

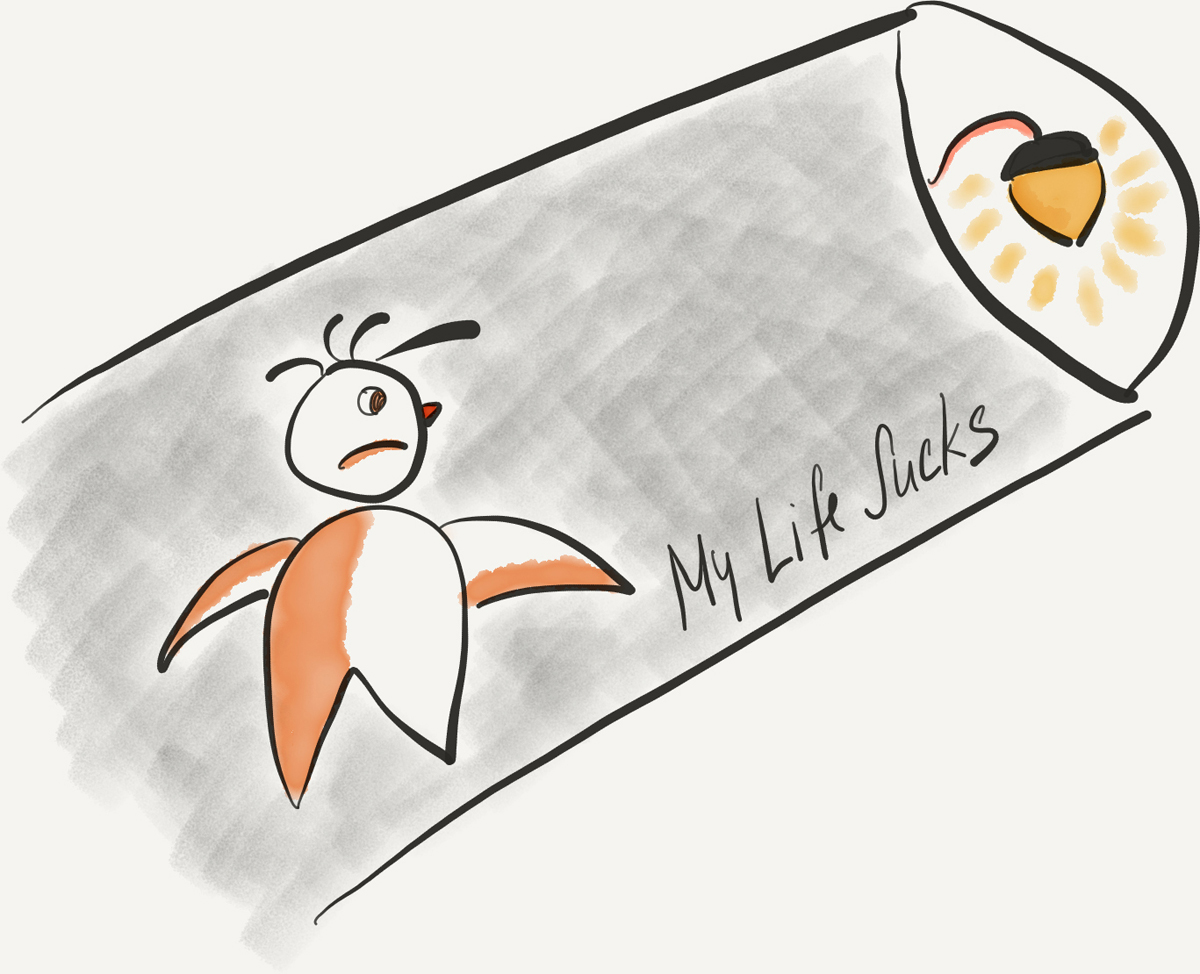

The second tribal type is “My Life Sucks.” Such tribes are common in the traditional Organization 1.0, where employees feel disrespected and demotivated and complain about everything. The tribes define steps on the mindset journey. In this tribe, you hear complaints such as “My life sucks because I don’t get paid enough,” “My life sucks because I have to drive two hours to and from work every day,” “My life sucks because I have an incompetent boss,” and even complaints about trivial, easily corrected issues: “My life sucks because we don’t have good coffee at the office.”

People in the My Life Sucks tribe can at least see the light at the end of the tunnel. Overall, only 25% of organizations are likely to have such a tribe in the majority. These organizations usually treat people according to theory X, and carrot-and-stick practices are the norm. You can see heavy micromanagement, employees trying to game the system, a high percentage of sick days, low retention, and literally no one who would stay if they won even a small lottery.

Let’s take a look at how you can help people to move to this level. Although the Life Sucks tribe is not that common, it’s important to start there, because for those who are in it, even the My Life Sucks belief represents significant progress. Life has no light at that first stage, so the first step could be to help them find friends from the second tribe. People in the My Life Sucks tribe are not that different—they are still not happy about things, but they already see the light.

The third tribe is “I’m Great (and You Are Not).” At this stage, people finally experience their own success and feel great. “I’m better than others,” they say. “I can do this, and they can’t. I’m a manager, and they are just employees.” “I’m great at my work, and they can never be that good at it.” This is one end of the spectrum. Managers at this end often generate employees in the My Life Sucks tribe. On the other end of the spectrum, you can see a good version of this tribal leadership stage: the specialization. “I’m great at visual facilitation,” “I’m great at explanatory testing,” “I’m great at UX design,” “I’m great at selecting chairs for our company.” The second part of the sentence (“and you are not”) is still there, just not that important, as everyone knows that everybody is great at something, and being great doesn’t mean others are not good. This tribe is a majority in about 49 percent of organizations. I’m Great represents the good version of the traditional organization and is typical for Organizations 2.0, which focus on knowledge and specialization.

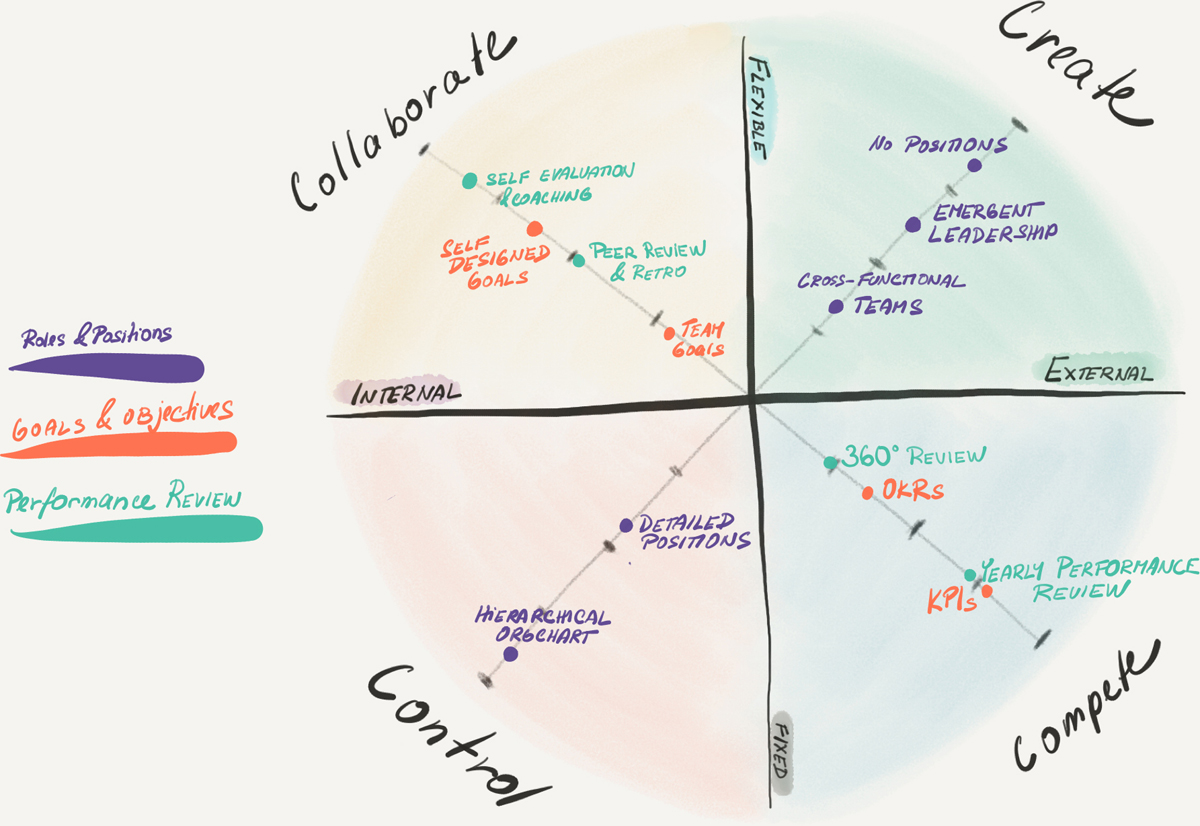

On the positive end of the spectrum of this tribal leadership stage, we aim for everybody’s success. People are different, everyone can be great at something, so let’s find it and make it happen. Let’s help everyone to be successful. All of the traditional practices, so typical in our organizations—such as an employee of the month, defined career paths, and detailed position descriptions focused on specialization, but also key performance indicators (KPIs), detailed goals and objectives, bonuses, and performance reviews—were invented to support this tribal leadership stage and help people to experience their individual success and move away from the My Life Sucks tribal leadership stage. In the I’m Great stage, the more individually successful people you can create around yourself, the better.

At this stage, there is a lack of collaboration; individuals feel happy when they are promoted but not particularly enthusiastic about the company as a whole. “It’s work like everywhere, I mean it’s not bad, I have a good job, they pay me okay, you know, it’s fine,” they would say when asked how they like their job. They might add a list of benefits the company is providing, but there is no real enthusiasm here either. In general, such employees like to chat with their colleagues, and if they won a small lottery, they might still hang out for a part-time job, as it’s a good distraction from being at home. You rarely see I’m Great people working from home or overtime. The work belongs only at work, they say.

The fourth tribal leadership stage is “We Are Great.” There is still a tiny bit of “you are not” in the background, but it’s not as strong as in the previous stage and not at the individual level. This is the world of teams, the world where agile starts to make sense. It’s the beginning of the agile journey. It starts with small teams that collaborate, help each other, and become better together. For the first time, it’s not about individuals but about teams. About 22 percent of organizations are likely to have this tribe in the majority. This is a great achievement. With the first few teams, the “we culture” starts to emerge. It’s not about individual success but about success as a team: “We are a great team (better than other teams in the organization).” People in the teams feel the identity, the belonging.

This stage is also about being proud on your organization: “We are a great company (and the other organizations are not as good as we are).” At this side of the tribal leadership stage, we start building networks of collaborative teams. The “we” is much broader and the collaboration much stronger. The cross-team collaboration starts picking up, and teams become less important again. The success of an individual team means nothing. We need to help each other and deliver the value together. The stronger we are as an organization, the better for the customers and the business.

The We Are Great stage is typical for Organizations 3.0, which embrace agility at the team level and have started their agile transformation by implementing some frameworks, such as Scrum,2 LeSS,3 or Nexus,4 or that are inspired by the Agile@Spotify5 example. Companies talk about business agility and agile out of IT. At the team level, we apply the theory Y—we believe that people don’t need many directions, that they are motivated and will take ownership and responsibility. At the organizational level, it might still be challenging, as organizations have inherited plenty of processes from the traditional world and forget to eliminate them. But in general, you see a trend of focusing on cross-functionality, which results in much broader job descriptions and flatter hierarchies; during their agile transformations, corporations’ organization charts typically are reduced from ten or more levels to around three levels. Organizations move from individual KPIs toward team-oriented goals, experiment with OKRs,6 and last but not least, move away from the variable part of the salary toward the higher base. The transparency is much higher, which results in their willingness to share case studies, blog about their agile journey, and share their stories at conferences. In business, they are still quite protective and focus on competing with other organizations.

Collaboration results in a strong sense of ownership, common identity, and a shared goal. People are motivated, they consider work as an integral part of their lives, and they have no problem doing some work from home or working overtime if necessary. They would recommend working for the company to their friends without any hesitation, and were they to win a small lottery, they might take a vacation but would soon be back at work. In general, if you want to shift a major tribe from I’m Great to We Are Great, implement agile.

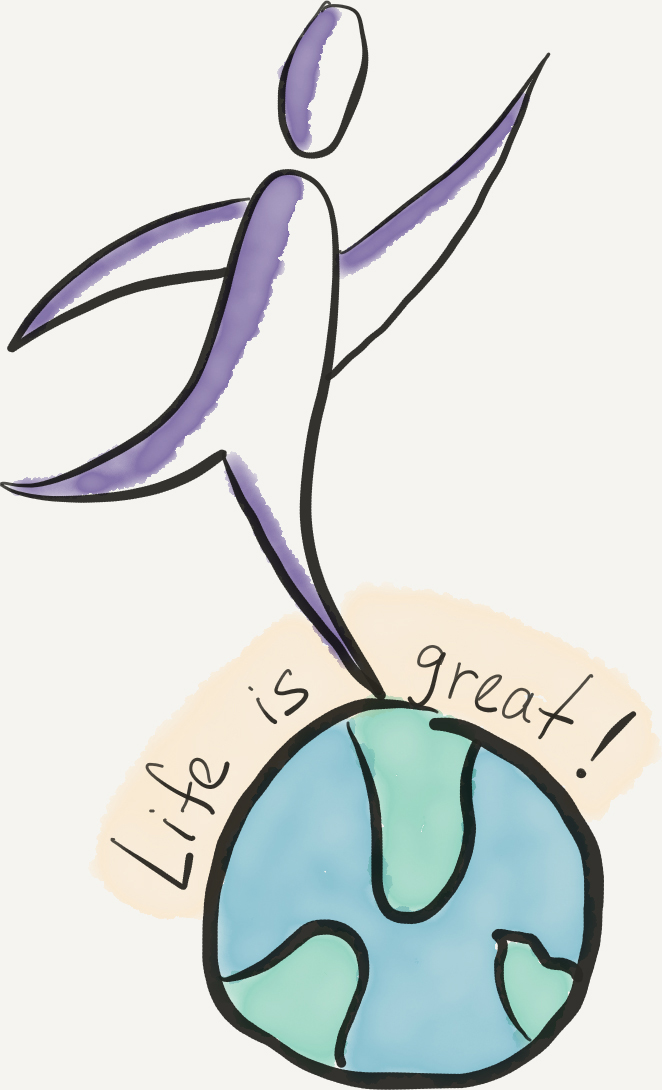

The final stage of tribal leadership is “Life Is Great.” This stage is still quite rare, and only 2 percent of organizations are likely to have such a tribe in the majority. It’s a place where you’ve achieved the agile mindset at the organizational level. There are no competitors—the other organizations in your space are potential partners for alliances and coalitions. They form flexible networks with others on their journey, and the evolutionary purpose is key for organizational success. It’s a world where 1 + 1 is more than 2. Radical transparency is a necessity. Such organizations are open to the public, organize tours for visitors, and share their knowledge insights.

This is the real agile organization, which is agile not only at the team level but at the organizational level as well. It’s a long journey for most organizations nowadays, but there are great examples already. You don’t need to be like them tomorrow, there is no hurry. Any organization needs to grow into that mindset. But already today, you can get inspired and start your journey.

DOING agile is not helping; you must BE agile.

At this level, people are enthusiastic about the purpose, and they do whatever it takes to achieve it. They collaborate and are highly receptive to new ideas from inside and outside. They often take very creative approaches that few have tried before. They have courage, focus, respect, openness, and commitment. They are not doing agile, they are living agile. When people with this mindset win the lottery, they’ll still be hanging around helping people to achieve their evolutionary purpose because they believe in it and because it matters to them.

If you want to shift the major tribe at your organization from We Are Great to Life Is Great, become agile at the organizational level. Make transparency and autonomy key organizational values, be open to experiments, see the organization as a network of collaborative teams, become customer-centric and purpose-driven. There are no competitors, and there are no boundaries imposed internally on the emergent leadership. Agile leadership needs to become the way of working and needs to be spread across the organization. Help people to grow and become agile leaders and support them on their journey. Become a role model of an agile organization and an inspiration for the entire industry.

The tribal leadership concept presents an interesting mental model for visualizing how you can see the mindset part of the culture evolving. No matter how fast you would like your organization to change, you can’t skip steps—you have to go one by one. There is no way to jump from the major tribe of My Life Sucks to We Are Great. The mindset doesn’t change that fast; however, it doesn’t have to take years—you just follow the journey and be consistent with following agile practices.

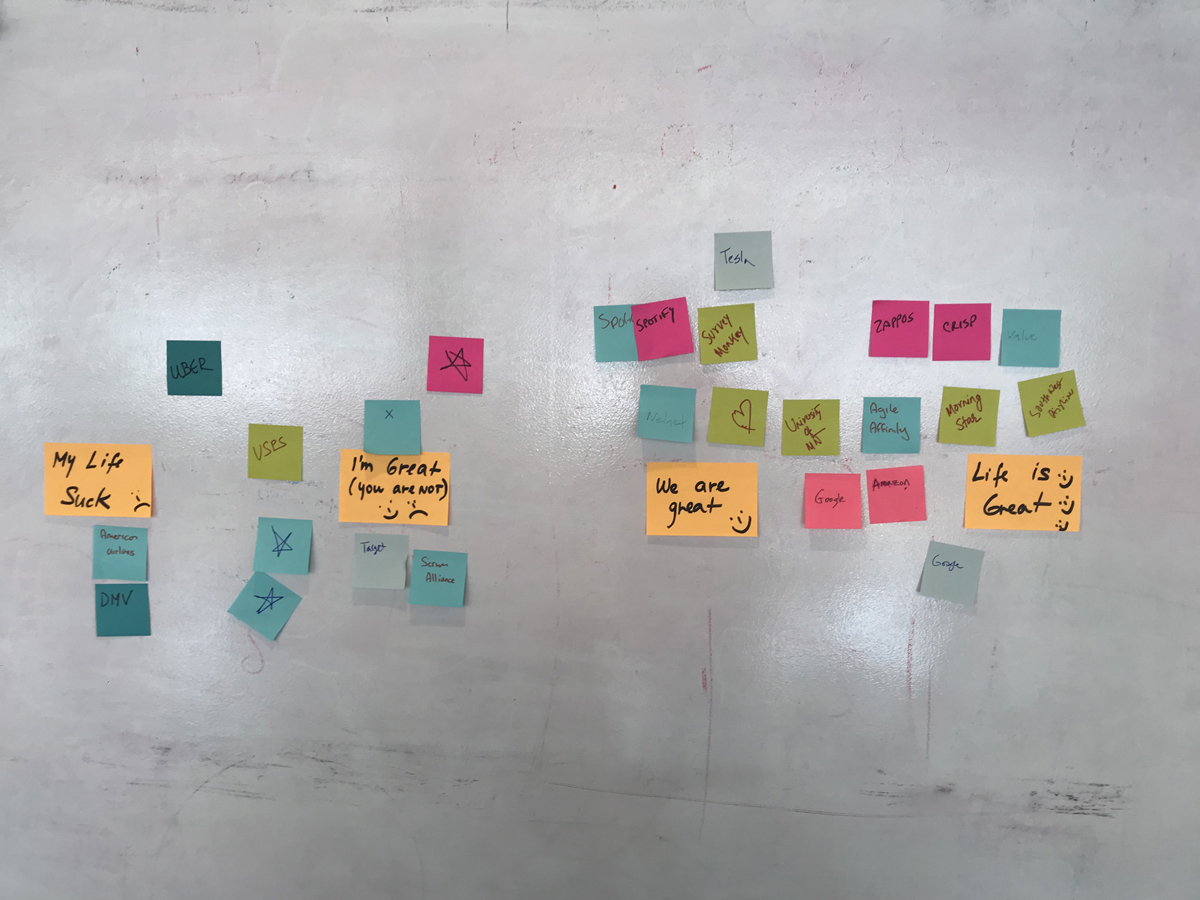

As an example, you can see how I use this model in a workshop setting to start a conversation about different organizations or different parts of one organization. Mapping companies to the tribal leadership model is not a right-or-wrong categorization. Rather, it’s a subjective exercise meant to open discussion about certain aspects of the organization. For example, Why do you see the organization there? and Where would you like to see it in the future?

The participants start by writing a Post-it Note with the name of their company or their part of the organization and placing it on the map where they believe the major tribal leadership stage is. Some participants prefer to use a symbol (e.g., star) instead, as they don’t feel safe about the map possibly being shared outside of the workshop participants. Then we talk about it, share stories, hear why they feel the major tribe is there. As a next step, they brainstorm other organizations just as an inspiration and to deepen the conversation. Again, it’s not about being right about those organizations, as there is no right or wrong anyway; it’s just a model to encourage discussion about where they see the different environments and why. The final step is to think about where they would like to see their organization or their individual department in the next year and what they can do about it.

Result of mapping companies to the tribal leadership model

Think about your organization. What is the major tribe at your organization (or your part of the organization)?

Life Sucks

My Life Sucks

I’m Great and You Are Not

We Are Great

Life Is Great

Where would you like to see your organization or department in a year from now?

Life Sucks

My Life Sucks

I’m Great and You Are Not

We Are Great

Life Is Great

What can you do about it?

When speaking about partnerships or alliances, the different tribal leadership stages of the parties will create a compatibility or misalignment and can be used to predict the success of such a partnership or alliance. Just imagine the organization in a We Are Great phase trying to build a business relationship with an organization with managers in the I’m Great stage and employees mostly in the My Life Sucks tribe. Their values are neither complementary nor aligned, and such a relationship is most likely going to fail.

As an example, in the organization I worked for, we built balanced partnerships with our customers. In an agile space, we often talk about the customer relationship, trust, and collaboration. It sounds simple. However, the mindset at both the company and the client need to be ready for such a partnership. To support that relationship, we changed the way we wrote contracts to reflect the partnership collaboration. Our contract didn’t define scope or timelines, it just reflected the way we intended to work together: use Scrum, collaborate, have a transparent backlog. With every Sprint we delivered value, we got feedback on it at the Sprint Review, and we planned a new Sprint if the value was still needed. There were no fixed deadlines; when the overall delivered value was good enough for the customer, we stopped. In a true agile environment, we don’t need that many processes around the business. We just take customers as an integral part of our process, are transparent with them, and collaborate.

Agile works great with such partnerships. However, it requires certain readiness of the mindset on both sides. If companies with the I’m Great (or lower) mindset doesn’t have enough trust in the We Are Great way of working, they will be looking for so many process assurances, regulations, and protection mechanisms that they will eventually kill the spirit of any partnership and will shift the overall mindset toward the lower tribal leadership stage or even one step below it. It’s as if they are speaking two different languages. On is looking for what-if scenarios, while the other trusts the collaboration, feedback, and transparency and strives to have the same understanding of the purpose. One side is questioning the motivation, while the other trusts the system and takes all the legal process assurances as redundant: we have the same goal, they say, let’s move on and achieve it together.

When you face a significant mindset disconnect, be patient and show the benefits to the other side step by step. Create a safe pilot project for the organization to experience it, and be a good guide for it on the agile journey. Changes take time, and changing the mindset takes twice as much time as changing the structure.

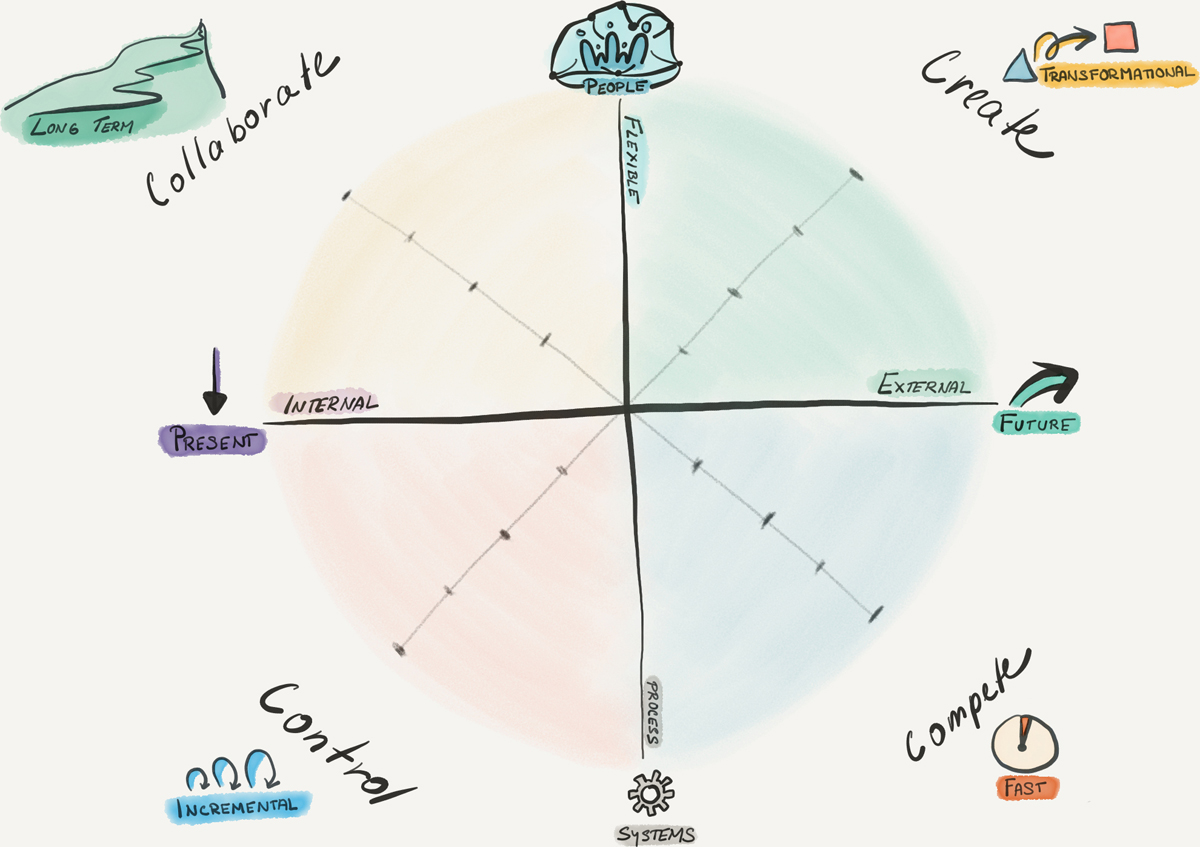

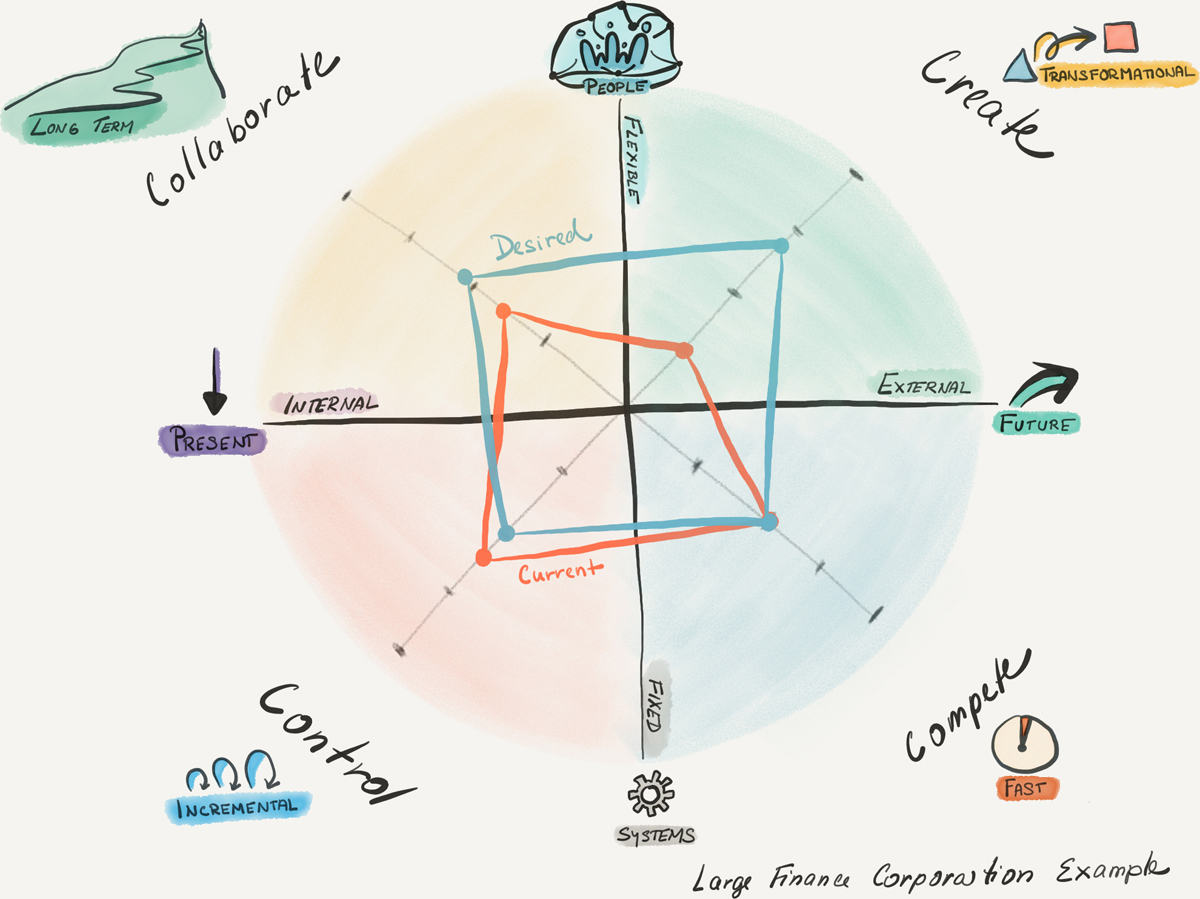

Competing Values

Culture is a complex system, and another way to look at it is to focus on the relationship of four competing values. The competing values framework7 is based on research of the major indicators of an effective organization and provides a different perspective on agile organizations. The top competing values are (1) present internal versus future external drive and (2) flexible versus fixed processes orientation. The competing values will result in four different culture quadrants—control, compete, collaborate, and create—which quite naturally stretch over the diagonal axes. Do we collaborate or compete? Are we flexible, or do we prefer to build long-term fixed systems within which to operate? In every organization, the culture is a mixture from all four quadrants, but the recipe for that mixture is always unique.

The very traditional organizations have a culture mix in which control and compete cultures are dominant, while agile organizations have a mix of mostly create and collaborate cultures. Within the Modern Agile [Kerievsky19] concept, the “make people awesome” and “experiment and learn rapidly” principles shift an organization to the northern hemisphere of the competing values framework. The We Are Great culture moves the organization from the compete to the collaborate segment, first at the team and eventually at the organizational level, while the Life Is Great culture makes the organizational collaboration even broader and spreads across the market, forming wider partnerships and alliances.

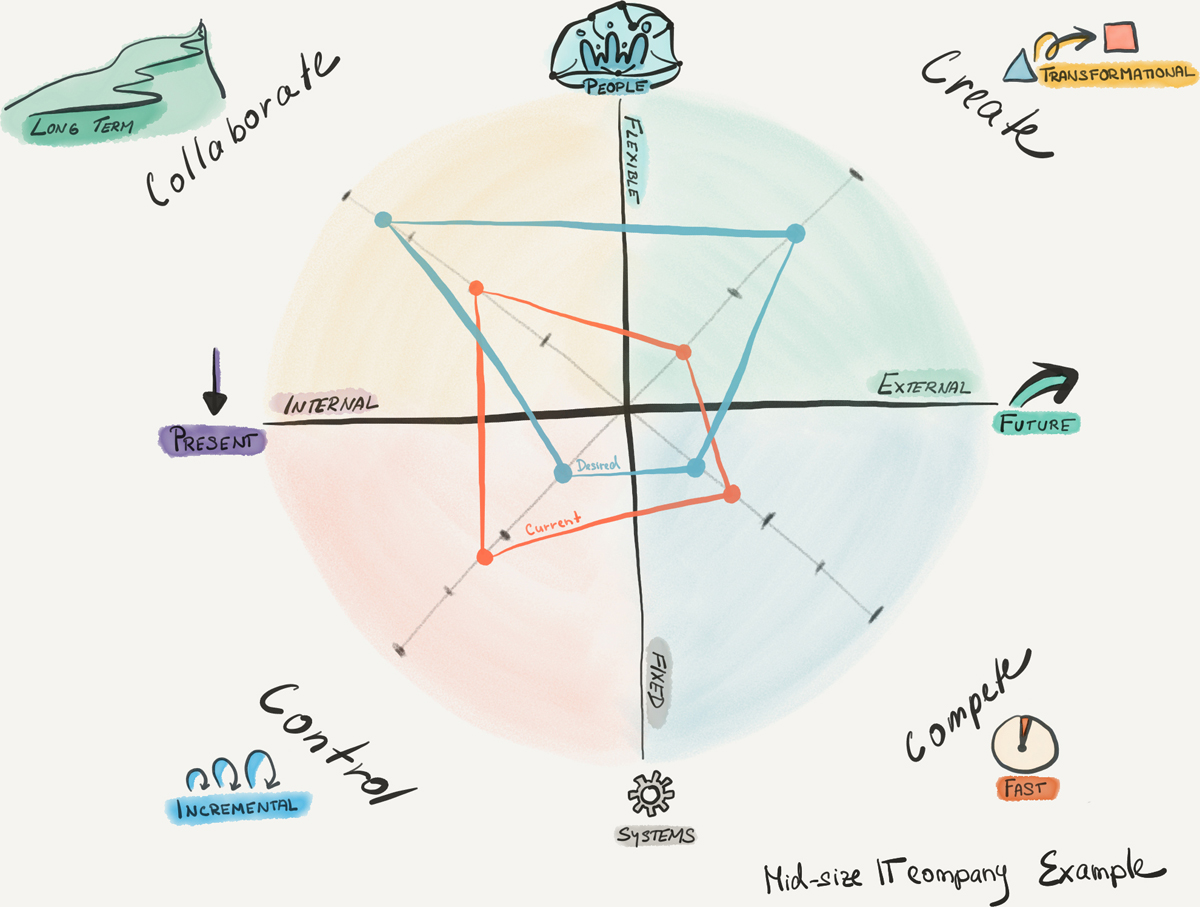

EXAMPLE 1: MIDSIZE IT COMPANY

As an example, let’s look at the midsize IT company I worked for a few years back, which was struggling with a lack of flexibility. The business demanded highly flexible cross-functional teams, which needed to learn fast. Each customer environment was so different that the pressure was tremendous to learn fast while keeping the focus on high technical excellence. It came to be too much. We were unable to grow people to the expected level, and we were failing to get up to speed fast enough with new customers. We had a traditional structure of functional departments, where most of them were quite hierarchical and process-oriented. We had a few agile team pilots but not organization-wide agile practices. The management was in the competing and protecting mindset, but the organization was collaborating. The innovations were close to zero, limited to the purely technical level.

When we started our journey to become an agile organization, we concentrated on high flexibility, creativity, and overall business focus while not compromising on technical excellence. We were aiming for higher collaboration, and as a result, we shifted to even higher cross-functionality and collaboration across the traditional roles. We decided to take a bold step and unleash the potential of our employees and support their creativity and innovations by moving significantly toward the create culture. The practices followed the vision of the culture shift: we descaled the organization to a very flat structure with only one level of management, based on self-organized teams; we broadened the positions and their descriptions; we got rid of fixed KPIs and moved to frequent peer feedback and coaching employees to grow; we created innovative camps where everyone could join and work on some creative idea and support communities and emergent leadership. This journey to the desired state took a little bit more than year until it was self-sufficient and growing and improving organically.

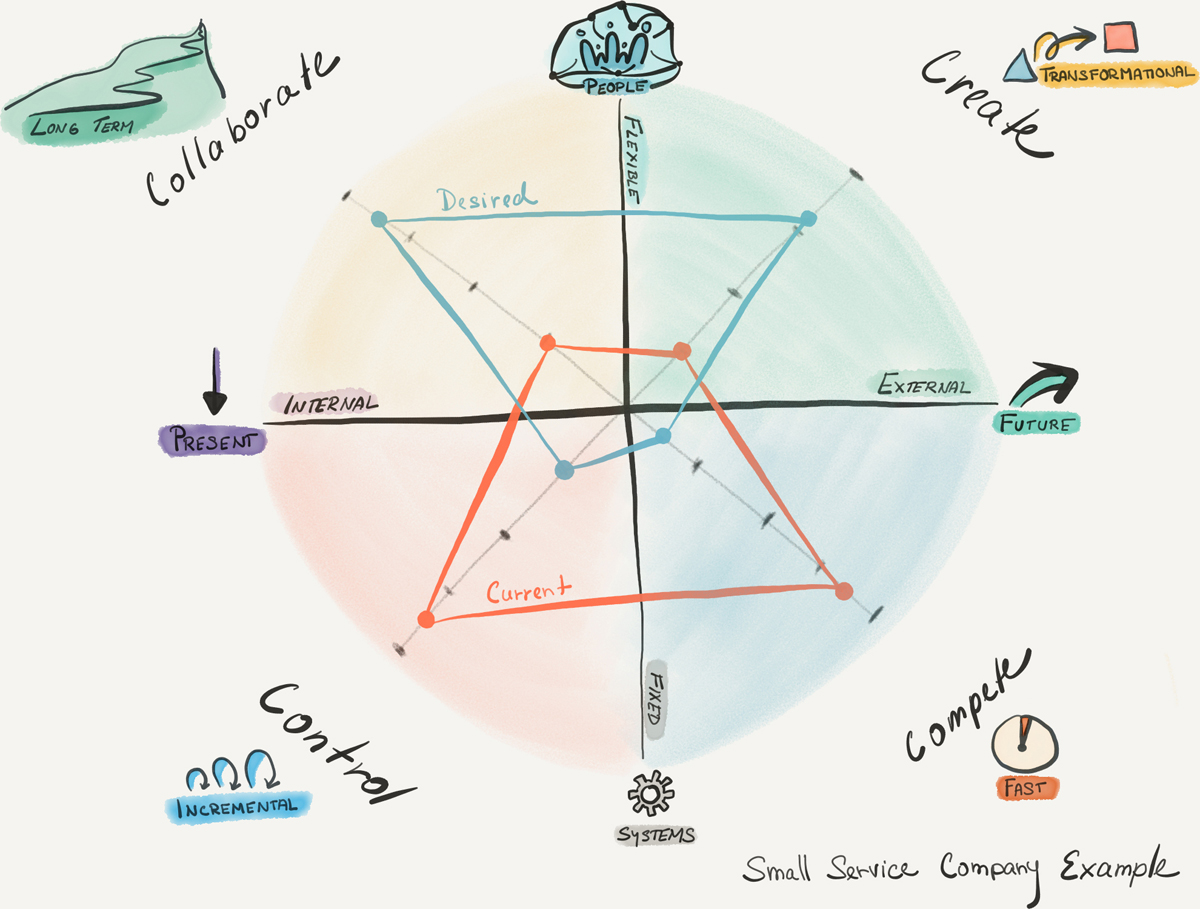

EXAMPLE 2: SMALL SERVICE ORGANIZATION

This example describes a small service organization. The organization had very hierarchical management and a toxic culture where people were competing with each other, and their key goal was to show they were better than others so they would get promoted. The situation resulted in huge demotivation. Many people were leaving the organization, and customers complained that the work delivered by the organization was not bringing any value to them because internal fights were more important than the customer-centric approach. The organization claimed it was agile, but “agile” was in name only.

Midsize IT company example

Small service organization example

When the management changed, its vision was very bold: change the organization to a flat structure based on self-organized cross-functional teams. It was a big shift from control and compete to collaborate and create. In one word, it was agile. The strong vision and evolutionary purpose made it possible. The transparency about the intended shift and voluntary participation in the new culture shift (stay and help or get a package and go) helped as well.

EXAMPLE 3: LARGE FINANCE CORPORATION

This final example is from large finance corporation I worked several years ago. This organization didn’t feel as strong a need to change its structure and the way it worked as the organizations in the previous examples. However, it still felt a need to become more agile—in this case, more innovative, adaptive, and flexible. The corporation felt it needed to give people a little bit more space, to flex its processes, and to be more team-oriented at the project level. But there was no intention of changing any of the individual-based practices or the management structure.

Large finance corporation example

The organization wanted to be more creative and innovative, to unleash the potential of its business and expand beyond banking. It wanted to be different from similar banks and to test prototypes quickly to create new services faster than its competitors. That vision was appealing and motivating and allowed the organization to run a set of experiments as Scrum pilots, Kanban teams, and innovative labs, and a couple of ideas were successfully transformed to the projects and delivered to the market.

Now that you’ve seen these examples, think about your organization and draw the current and desired stages on the picture. Where are you now? Where would you like to be?

No matter how close or far the desired state of the organizational culture is, think about three actions you can take right now to get closer.

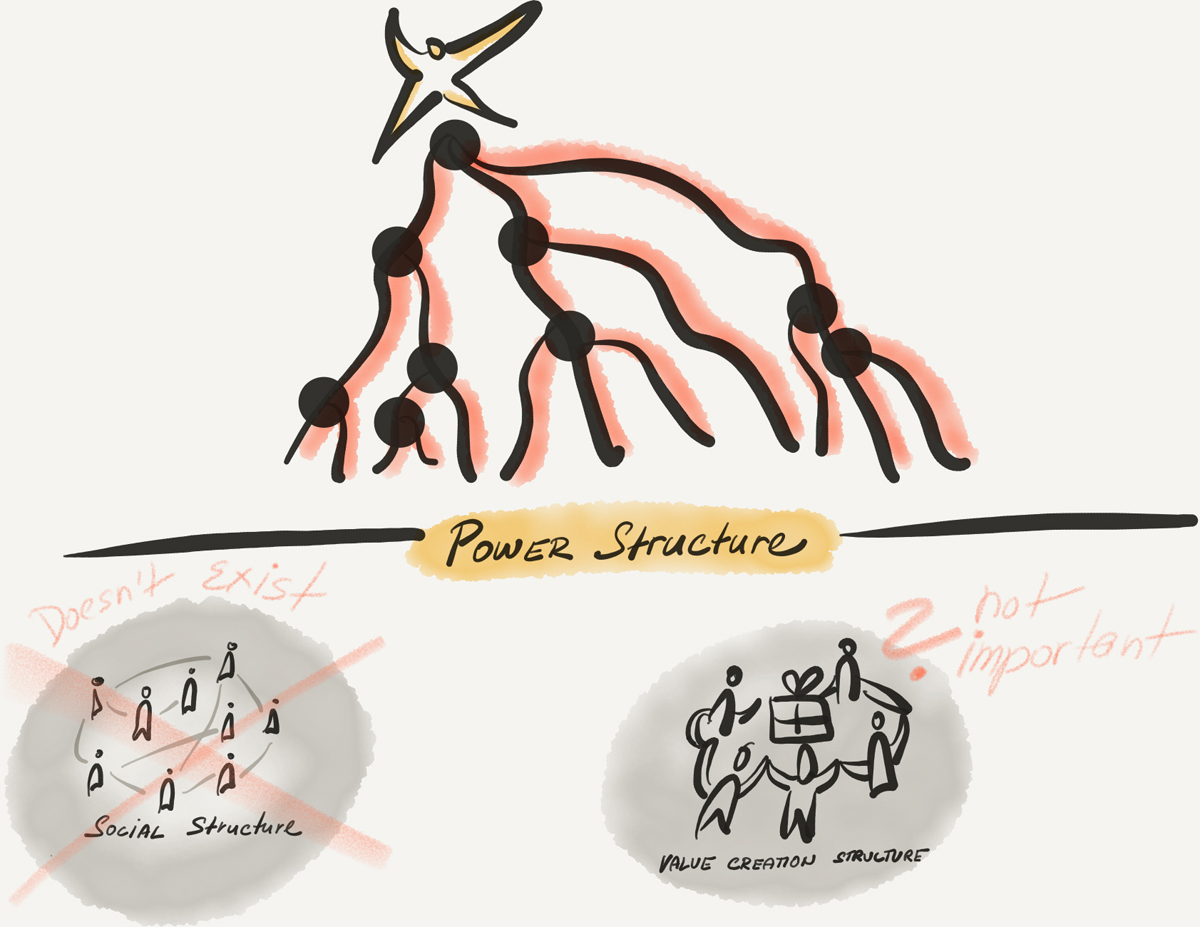

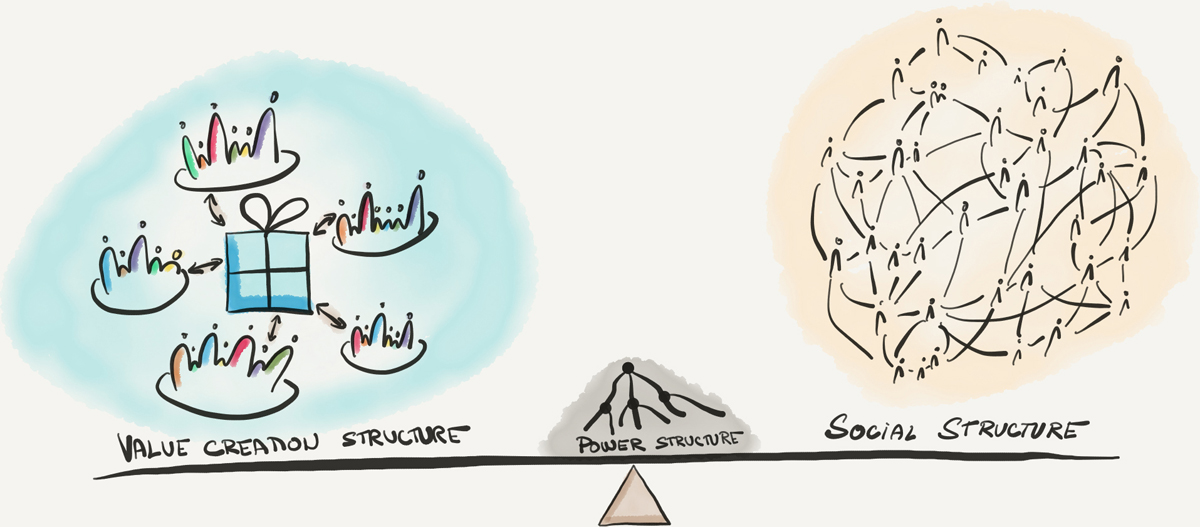

Network Structure

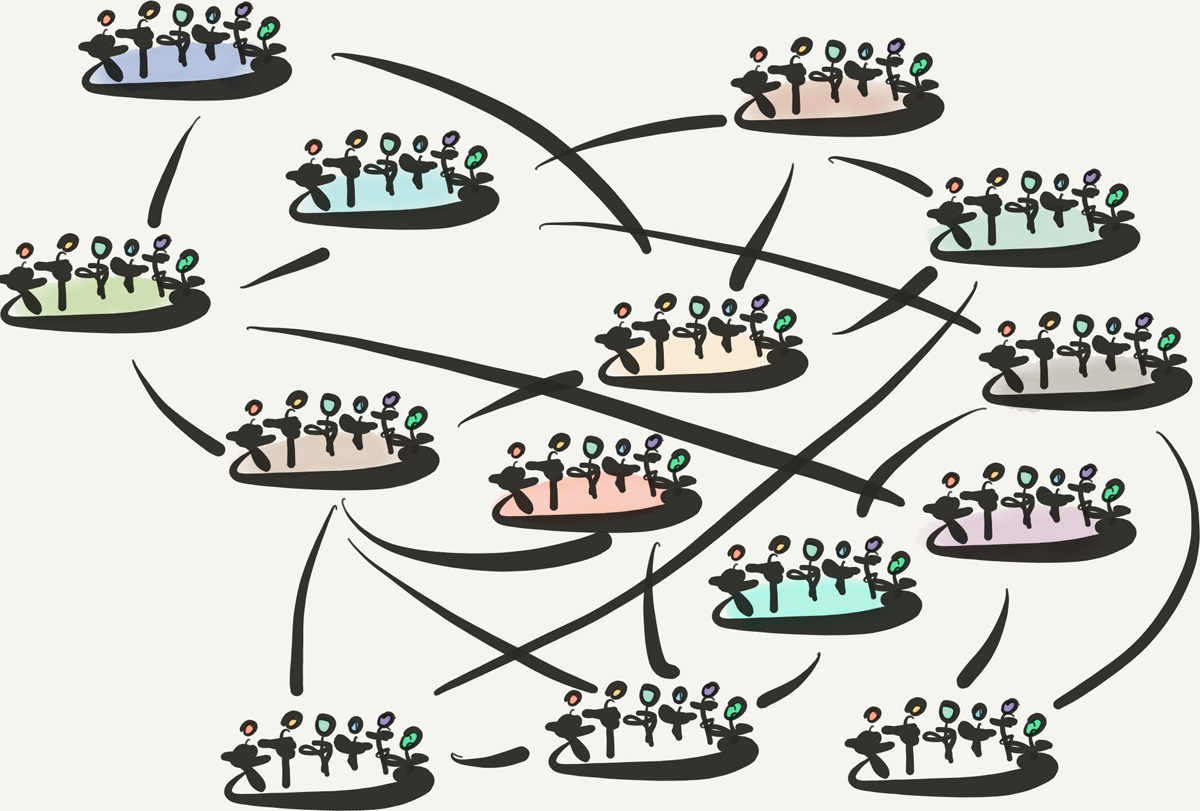

Some organizations don’t have an obvious center. The hierarchical power structure is not the only structure that exists in organizations. There is a social structure, which is built on top of relationships and social interconnectedness, and also a value-creation structure [Pflaeging17].

Organizations based on power structures are simple to understand, simple to manage, simple to operate. They simplify the decision-making process and responsibilities. They can also be superefficient if they are designed well. Their biggest disadvantage is that they deal with lack of empowerment, which often causes demotivation and disconnect of the employees from the value they are supposed to deliver, but more important, they lack the flexibility and creativity to deal with VUCA challenges.

Traditional organizations like to avoid complexity. Therefore, they try to simplify the decision-making process by having clearly defined power structures and pretending that social structures don’t exist or are not important, since the organization is supposed to be driven by the set of rules and processes and is supposed to use linear thinking to address the value delivery piece by piece. Tools such as Gantt charts8 and the critical chain method,9 as well as typical linear issue-tracking systems such as Jira,10 come from this world.

If during your agile journey you make the hierarchical power structure less important, organizations don’t fall into chaos, as they can still stick together through the social and value-creation structures, which become much more important in such cases. In agile organizations, when people want to exert influence, they need to be part of the community that is responsible for that issue; if they want to work on a certain value, they need to be part of that product team. Agile organizational transformations happen through radically decentralizing decision making and simplifying the organizational structure by “descaling the number of roles, dependencies, architectural complexity, management positions, sites, and a number of people” [Grgić15], as it is defined by the LeSS framework, for example.

At their core, agile frameworks usually focus on strengthening the value-creation structure and making it the most important part of the organization. We talk about value streams; the customer-centric, value-driven approach; and using the Story Mapping,11 Impact Mapping,12 and Lean Startup13 methods. No matter how strong the focus is on the value structure, it’s not enough by itself—the social structure is equally important. At the end of the day, it’s all about the mindset.

Smart versus Healthy

Focusing on individuals and interactions, building great teams, and creating an environment where people can collaborate freely is key to the organizational success. Frameworks and methods by themselves will not help, and without the right mindset, organizations will fail to implement them no matter how hard they keep trying. That might be the hardest part of agile. Don’t take me wrong—tools are handy because they help you to not get lost on a day-to-day basis, frameworks are helpful because they give you some boundaries, and processes are useful because they give you predictability and common ground in the constantly changing world. However, by themselves, they are not enough. In order to be successful with agile, the social structure needs to be supported as well. Patrick Lencioni, in his book The Advantage: Why Organizational Health Trumps Everything Else In Business [Lencioni12], describes two requirements for success: being smart (strategy, marketing, finance, and technology) and being healthy (minimal politics, minimal confusion, high morale, high productivity, and low turnover).

“Being smart is only half the equation in a successful organization. Yet it somehow occupies almost all the time, energy, and attention of most leaders. The other half of the equation, the one that is largely neglected, is about being healthy” [Lencioni12]. Organizations spend way too much time on the smart side, focusing on strategy, marketing, finance, and technology, so they have no capacity left to minimize politics, confusion, and turnover while focusing on high morale and productivity. “None of the leaders—even the most cynical ones—deny that their organizations would be transformed if they could achieve the characteristics of a healthy organization. Yet they almost always gravitate to the other side, retreating to the safe, measurable ‘smart’ side of the equation” [Lencioni12].

How much time do you spend on the smart versus healthy aspects of the organization?

What can you do to improve the healthy focus?

While working with individuals is important, it has only a limited effect on the organization. “What really improves a system as a whole is working not on the parts itself but on the interactions between the parts” [Pflaeging14]. And that is exactly where the agile leadership effort should be focused. Not on how to work with individuals—that was a realm of traditional management—but on how to work with systems, teams, and the relationships among people. It’s what happens between people that matters. From such a perspective, the organization can be seen as a network of teams, where the lines are the key point of the focus. “You are not here to solve the issues for them, you are there to help them straighten their relationship so they can work towards the resolution” [Šochová17b].

Even though organizations look different in the agile space, they still have some sort of structure—it’s just the power structure that is very limited and not as influential as in traditional organizations. There is no exact model to follow. In fact, there are many examples: organizations based on fully cross-functional teams and self-management; flat organizations;14 Spotify15 and its tribes, chapters, and squads; organizations that implement holocracy;16 and those that aim to be teal organizations17 (see Chapter 1). There is a lot to choose from, but in the end, all of them are going to be hard to implement, as they require changing the organization down to its roots. All of them are trying to solve the same problem: how to survive in the VUCA world, how to be super-adaptive and flexible, and how to deal with complexity and ambiguity. Simple to say, hard to do for organizations that are used to planning projects, budgets, and goals in yearly cycles and to optimizing for fixed repetitive tasks.

Cross-functional and Community-centric Teams

Melissa Boggs, Chief ScrumMaster, Scrum Alliance

At Scrum Alliance, we found ourselves at our own crossroads. When I stepped into my role in January 2019, we were not built in such a way that we could listen closely or move quickly. Ideas were often lost in the maze of hierarchy and approval processes. Some of our team members felt stifled and unable to creatively problem solve. We could continue going down the same road and get the same results, or we could choose to rethink our way of working.

In recent months, we have rebuilt our organization into cross-functional and community-centric teams empowered to deliver. We have flattened hierarchy to eliminate red tape and place decision making with those closest to our community. We have embraced agile values and principles wholly and deeply and as an organization. It’s been hard work, for the entire team, but it’s worth it. Slowly, we are starting to see the fruits of our labor, evidenced by candid conversations with each other and with our customers. We’ve increased our ability to change course on the basis of those conversations. We are buoyed by the laughter and energy in the office as new ideas are introduced and collaborated upon.

We are proud of our commitment to learning what it takes to live out the Scrum values every day, and in doing so, we are joining others leading the agile movement. We understand from experience that it feels risky. We’ve been trying things we have never tried before and letting go of control in places we’ve tightly held. The good news is that it’s opening doors we never knew existed, and we are thrilled to be sharing what we’ve learned with you.

We are all at a crossroads. Which path will you choose?

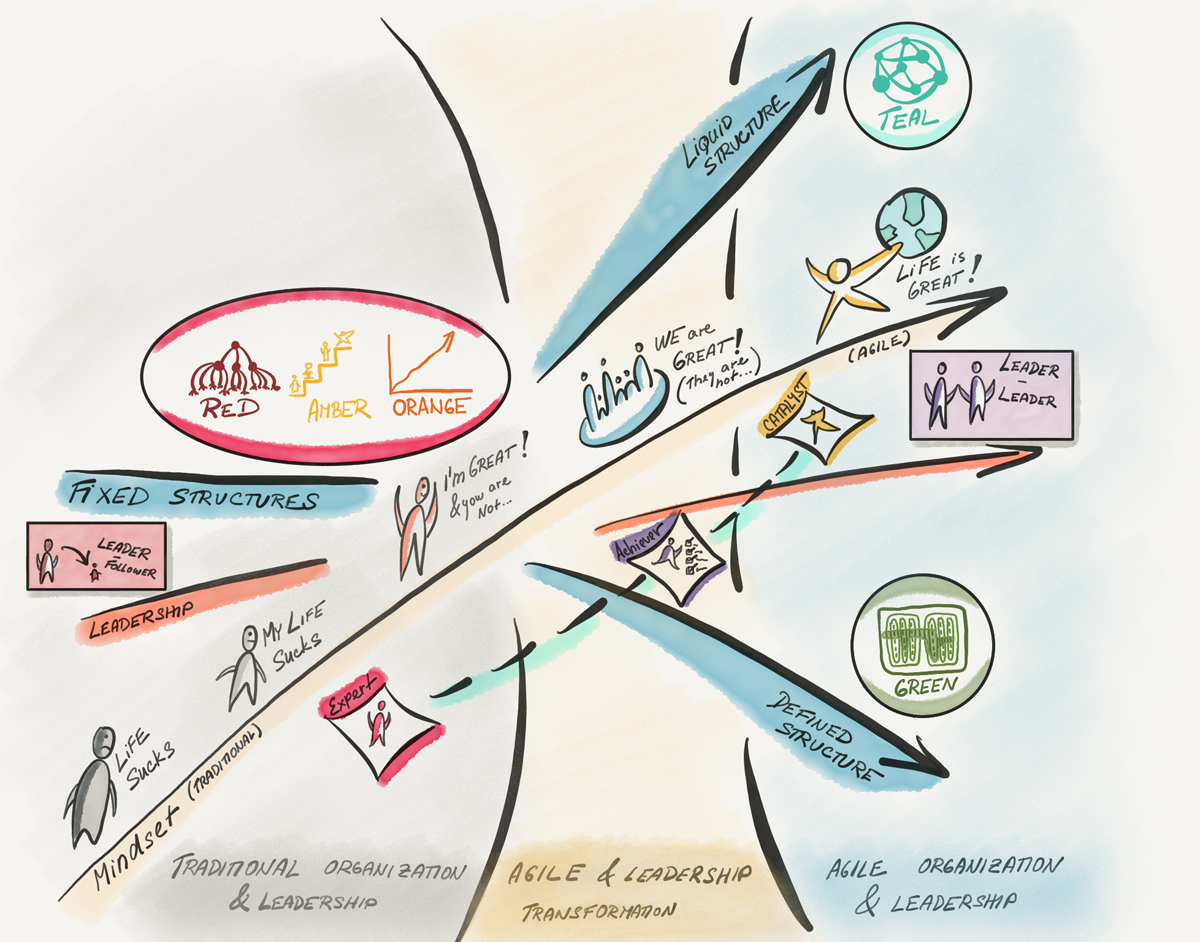

Reinventing Organizations

One very popular book in the space of agile organizations is Reinventing Organizations by Frederic Laloux [Laloux14]. It classifies organizations by color. It starts with the red organization, which is the pure command-and-control organization where hierarchy, power, and fear are key artifacts and no one shall even think about moving a different way; proceeds to the amber organization, which is still heavily reliant on hierarchy, processes, and formal role definitions to bring stability and control; and finally to the orange organization, which is where most of the traditional organizations land, focusing on the profit, competition, and clear goals and objectives. All three categories are just different representations of traditional organizations. They all rely on hierarchy, and they all expect fixed structures to define the decision-making process, responsibilities, and work to be done. In the orange world, we talk about innovations, but they rarely happen, as the organization is so tied to its way of working that there is only limited space to react to new challenges.

The red, amber, and orange structures are often operating with the majority of people from the My Life Sucks and the I’m Great and You Are Not tribes. For example, when the managers are on the left side of the spectrum of I’m Great and You Are Not, most of their employees end up quite naturally at My Life Sucks. Though the two models exist in different dimensions, it’s still useful to see how they often overlap.

Example of mapping companies to the Reinventing Organizations model

At the agile end of the spectrum, we have green and teal organizations. They no longer have a fixed structure because they have optimized for adaptiveness. The biggest difference between the two is that green organizations still have a defined structure, even though it’s a flexible one, while teal organizations have a liquid structure. Green organizations focus on culture: they talk about empowerment, engagement, and shared values. They also focus on delighting the customer, balancing different stakeholders, and delivering value. Teal organizations, with their liquid structure, are driven and interconnected by a higher evolutionary purpose, which creates their wholeness and togetherness. Without it, the teal organization would fall apart, leaving only chaos behind. Teal organizations build on self-organization and emergent leadership, so that the decision making is distributed. Both green and teal organizations are optimized for complexity, give people higher autonomy, experiment with new approaches, and are very much business-value driven.

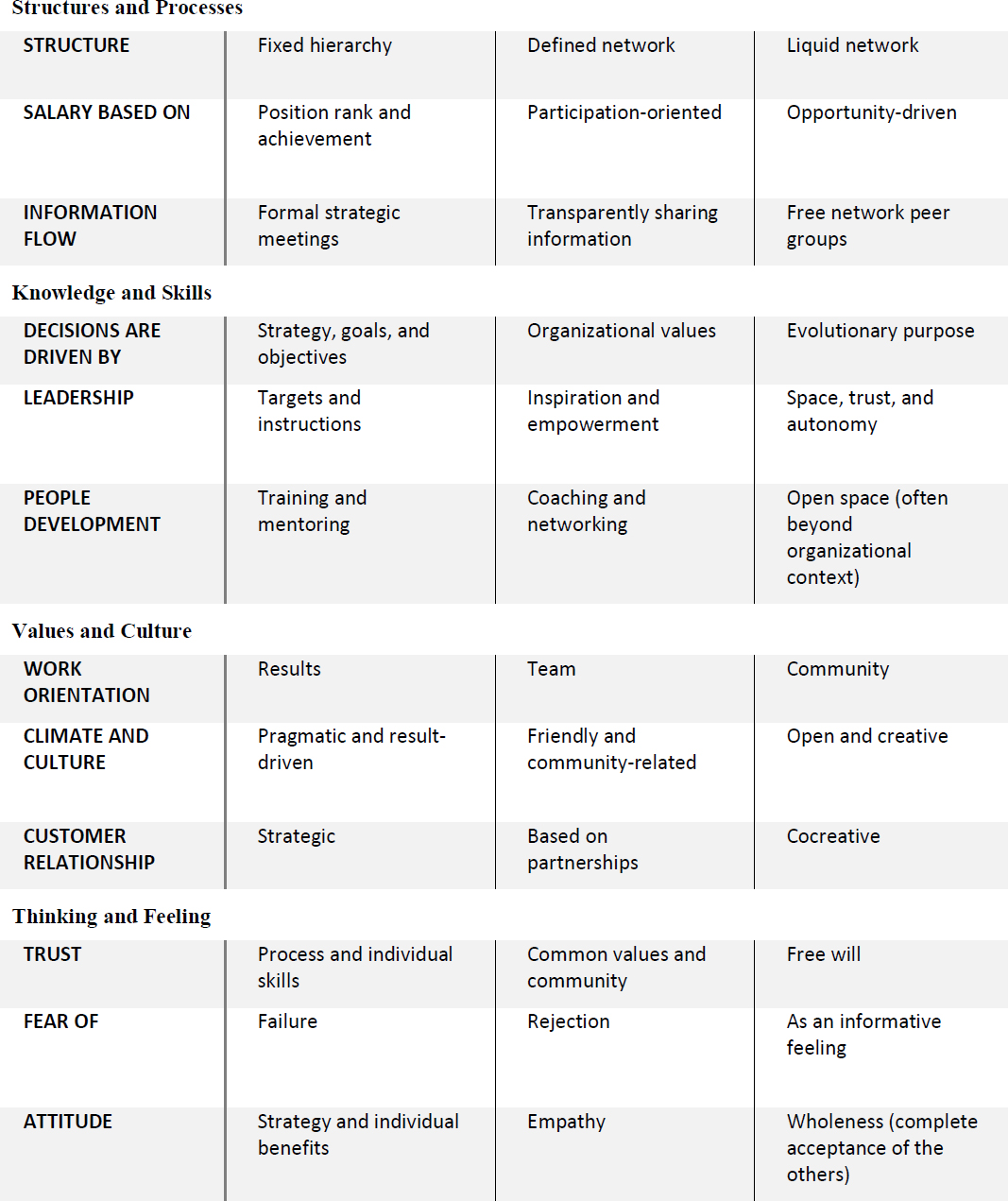

Think about where your organization or department is right now. From the three options, mark the one that is the closest fit.18

Items in the first column are characteristic of traditional organizations (red, amber, orange), items in the middle column are characteristic of green organizations, and items in the last column are characteristic of teal organizations.

The assessment will show which type of organization you lean toward.

Where would you like to see the organization in the future? What can you change in the organization to get there?

Books to Read

Tribal Leadership: Leveraging Natural Groups to Build a Thriving Organization, Dave Logan, John King, and Halee Fischer-Wright (New York: Harper Business, 2011).

Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness, Frédéric Laloux (Brussels, Belgium: Nelson Parker, 2014).

The Advantage: Why Organizational Health Trumps Everything Else in Business, Patrick Lencioni (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2012).

Company-wide Agility with Beyond Budgeting, Open Space & Sociocracy, Survive & Thrive on Disruption, Jutta Eckstein and John Buck (Braunschweig, Germany: Verlag nicht ermittelbar, 2018).

Organize for Complexity: How to Get Life Back into Work to Build the High-Performance Organization, Niels Pflaeging (New York: BetaCodex Publishing, 2014).

In a Nutshell

The agile organization is like a star on the horizon: you can never reach it, but you can get closer, step by step.

There is no specific framework needed to become an agile organization. All you need is to practice agility at all organizational levels.

Sustainable agility is only achievable from the inside out. Start by changing the values and shifting the mindset from the inside.

In a well-functioning agile organization, leadership is nonhierarchical but is spread around and decentralized.

If enough people change their mindset, the culture changes and the organization become an agile organization.

Green and teal organizations optimize for adaptiveness, have a higher level of flexibility, and are better at dealing with VUCA challenges.

1 Courage, commitment, focus, openness, and respect are the five Scrum values.

2 Scrum: https://www.scrumguides.org.

3 Large-Scale Scrum (LeSS): https://less.works.

4 Nexus: https://www.agilest.org/scaled-agile/nexus-framework.

5 Scaling Agile@Spotify: https://blog.crisp.se/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/SpotifyScaling.pdf.

6 Objectives and key results (OKR) is a framework for defining and tracking objectives and their outcomes popularized by Google: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OKR.

7 The framework was originally described by R. E. Quinn and J. Rohrbaugh in “A Spatial Model of Effectiveness Criteria: Towards a Competing Values Approach to Organizational Analysis,” Management Science 29(3): 363–377, 1983.

8 Bar chart that illustrates a project schedule. Named after Henry Gantt, who described it in 1910.

9 Method of planning based on theory of constraints described by Eliyahu M. Goldratt in 1997.

10 Issue-tracking system by Atlassian and popularized by software development teams.

11 Story Mapping (Jeff Patton): https://www.jpattonassociates.com/user-story-mapping.

12 Impact Mapping (Gojko Adzic): https://www.impactmapping.org.

13 Lean Startup (Eric Ries): http://theleanstartup.com.

14 For example, Valve (https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-24205497) and Morning Star (https://corporate-rebels.com/morning-star).

15 Spotify engineering culture (https://labs.spotify.com/2014/03/27/spotify-engineering-culture-part-1).

16 For example, Zappos (https://www.zapposinsights.com/about/holacracy).

17 For example, Buurtzorg (https://www.buurtzorg.com/about-us/buurtzorgmodel) and Patagonia (https://www.virgin.com/entrepreneur/how-patagonias-unique-leadership-structure-enabled-them-thrive).

18 This assessment is based on the Reinventing Organizations Map designed by Emich Szabolcs and Károly Molnár [Szabolcs18]: https://reinvorgmap.com.