Baseline (B):

■ Create the vision.

■ Train the leadership and implementation team in Lean.

■ Charter the team, scope the project.

■ Select the pilot area and team members.

■ Conduct five-day Lean training seminar.

■ Baseline metrics, identify the “gaps” and set targets.

■ Build a chronological file—take photos and videos of how it is today.

■ Health check.

■ Value-stream map: current, ideal, and future state.

■ Determine the customer demand and takt time (TT).

Assess/Analyze (A):

■ Involve all the staff to analyze the process.

■ Process-flow analysis (PFA)—become the customer or product. This includes a point-to-point diagram of how the product flows.

■ Create process block diagram.

■ Group tech analysis (if required).

■ Workflow analysis (WFA)—become the operator. This includes a spaghetti chart of how the operator works.

■ Setup/changeover analysis (SMED).

Suggest Solutions (S):

■ Update the process block diagram—one-piece flow vision for the process.

■ Create the optimal layout for the process.

■ The ten-step process for creating master layouts.

■ Design the work stations.

■ Create standard work.

■ Determine the capacity and labor requirements.

■ Make and approve recommendations.

■ Train staff in the new process.

Implement (I):

■ Implement the new process—use pilots.

■ Start up the new line.

■ Update standard work.

■ Determine capacity and staffing (PPCS).

■ Implement line balancing.

■ Implement line metrics.

■ Visual management—Incorporate 5S, visual displays, and controls.

■ Implement Lean materials system.

■ Implement mistake-proofing.

■ Implement total productive maintenance (TPM).

Check (C):

■ Do you know how to check?

■ Check using the visual-management system.

■ Heijuka and scheduling.

■ Mixed model production.

Sustain (S):

■ Document the business case study and results.

■ Create the Lean culture.

■ Create a sustain plan.

■ Upgrade the organization.

■ Ongoing leadership coaching.

Why Is the BASICS Model Different Compared to Point Kaizen Events?

Many of you reading this book have probably already implemented Lean or think you have already taken Lean as far as it can go. No matter how far down the Lean maturity path you may think you are, we believe, based on our past and current client experiences, you still have lots of opportunities and room to improve.

BASICS is a different implementation approach with a much higher sustain rate* versus traditonal point kaizen events or WCM major kaizen. BASICS is a system-level approach designed to take more time up front to involve everyone in studying and analyzing the current process and set the target for the future state condition. It typically takes anywhere from one to ten weeks to study, implement, and run the line,* as well as getting 5S and lineside materials in place. We train the leadership, pick a pilot, and use small dedicated teams, with 100% operator and team leader involvement to manage the conversion from batch to flow.

This time frame is based on how much total labor time exists to produce one complete piece in a manufacturing line, one patient in a healthcare process, or one complete activity within a transactional process. For processes with very lowtouch-labor, i.e., less than three minutes per piece, we can analyze it and have the new line up and running in a week. Then we spend two to four weeks teaching team leaders how to run the line, create visual scheduling, standard work, and material flow systems. For lines or processes with longer total labor times it can run up to eight to ten weeks. This approach can also be used on converting station-balanced lines to bumping† lines.

In every case where we have applied this approach we have been able to obtain significantly better results in less than eight to ten weeks as compared to implementing using only five-day point kaizen events or major kaizen in WCM, which can take up three to five years or more.

The BASICS model yields much higher productivity in less time than traditional point kaizen events.‡ BASICS has the added value of seeing the process from a systems perspective, which allows for very innovative solutions in healthcare that would virtually never be found using traditional point kaizen events.

We even use the BASICS model in hospitals, clinics, and laboratories, which takes on average 12–14 weeks to complete an implementation. This approach, because of the systematic view, applies to a variety of industries and services. One of the key concepts that separates BASICS from other approaches is its simplicity.

The BASICS Model and Transactional Processes

Within most companies, transactional costs are often hidden, not well understood but still included in overhead. There is little to no knowledge of current transactional capacity or current performance against that capacity and overhead costs are embedded in many locations on the traditional P&L statement.

For example, much of the waste in manufacturing and transactional processes is included in the time standards. The days of the official stopwatch man are now gone. What’s left are five- or ten-year-old time standards that can no longer be met due to all the wastes growing in the process.

For example, in the general and administrative (G&A) section of the P&L statement, we often find costs for contracts, central accounting, legal, marketing, and the executive staff. The typical G&A costs can be large and are thought of as fixed.

The reality is the consumer considering a new car purchase would not want to pay for an option on the window sticker entitled G&A costs; however, those costs are real and are concealed in every car made by every manufacturer. Also, there can be overhead costs related to direct labor and they are shown as a separate line on the P&L.

Every business has transactional processes, while some businesses are virtually all transactional processes (i.e., banking and insurance). Every business, healthcare institution, financial services, and governmental agency can apply Lean, streamline their processes, and eliminate waste. By its very nature transactional processes are 95% non‒value-added.

Financial, human resource, and sales and marketing processes are not activities a customer wants to pay for; but, they are required to keep a business viable and effective. These processes supply companies with the data necessary to make the strategic decisions required to stay in business and provide the customer with better products and services at a lower cost.

When implementing office or administrative-type processes, we yield the same results:

■ 80% reductions in throughput times (weeks to days or days to hours)

■ 80% reductions in work in process (WIP) (amount of paperwork, sometimes e-mails in the process)

■ 30%–50% or more increases in productivity

■ 80% reductions in (non-electronic) travel distances

■ 10%–20% increases in quality

At many companies we see Lean savings charts, and when we ask, “Are those bottom-line savings?” we find most are paper-savings where, for example, they freed up 0.7 of a person. We see much of this paper-savings in WCM implementations. This doesn’t get to the bottom line unless you can make that person productive somewhere else. The book and the movie by Goldratt called The Goal * does a great job of emphasizing this point.

The BASICS model is 50% scientific management and 50% change management. It is a Lean approach, which targets an entire transactional process, i.e., accounts payable, or production line. In a hospital, for example, it will target an emergency room “system” or surgical “system.”

The BASICS Model

The main objective of creating the model was to present an easy-to-use roadmap. This roadmap helps to guide the users on what should be occurring as you move through a Lean implementation.

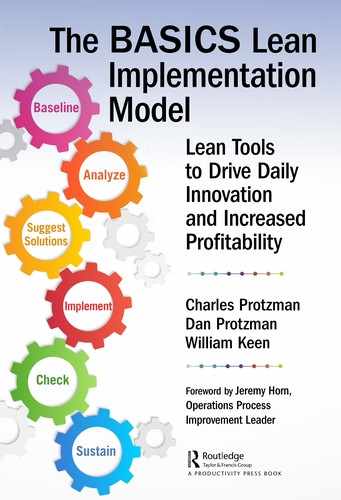

BASICS is a simple method and stands for:

1. Baseline

2. Assess/Analyze (Study)

3. Suggest Solutions

4. Implement

5. Check

6. Sustain

Implementation Phases

In our approach there are four implementation phases, which are incorporated into the BASICS model. These phases are:

1. Implement the line: Includes Baseline, Analyze, Suggest Solutions, and Implement

2. Implement standard work and visual heijunka scheduling

3. Implement the line side and supermarket logistics systems

4. Sustain the overall system implementation

At the end of Phase 1 we have the line up and running. This phase will realize 80% of the productivity results. In one large plant in Buffalo, New York, we rolled out phase 1 of this model on 14 lines over a 16-week period. Thirteen of these lines were already considered “world class for Lean” based on their Value-Based Lean Six Sigma Master Training. Overall we obtained 10%–50% increases in productivity and freed up 16 people,* iwhich immediately impacted the bottom line.

There was one line that was originally batched where we obtained a 70% productivity improvement (units per hour) and on one of their world-class lines we obtained a 377% increase in pieces (pcs) per person per hour going from ten people on two shifts to 2.7 people on one shift. This plant outside of Buffalo is still sustaining at high levels and growing their business.

At another company in Buffalo, we were able to bring offshore business back to a union facility with one of the highest labor rates in the country.

We still use point kaizen events with the BASICS model for setup reduction, rapid kaizen, and sustaining, but we still follow the BASICS methodology during the point kaizen event.

Lean and Layoffs

Our goal has always been to never layoff any permanent employees as a result of continuous improvement, and to date we have lived up to that goal. We have, however, laid off contract/temporary workers.

This goal has been a key driver to sustainment and continued improvements. If you do layoff anyone due to improvements, the operators will stop helping you improve. If layoffs are looming due to a business condition or merger, etc., make sure they are not associated with your Lean efforts. Many times, we get the president to send a letter to employees that supports this prior to starting the Lean implementation.

The Lean Practitioner Principles

When applying Lean tools, in any capacity, it is important to keep Lean principles in mind. When I first started working with hospitals in 2001, outside the lab, there weren’t any true benchmark sites or places to go and see. I was left to my own devices to figure out the best way I knew how to implement Lean in healthcare. I succeeded by following these ten principles as my guide, and they have not failed me yet. If you learn to apply these principles and tools from this book you can improve any process.

The Ten Fundamental Practitioner Principles

1. The customer must be willing to pay for it.

Without the customer we don’t exist. Everything must start with the customer. Do you really know your customer, and what problems are they trying to solve?

2. Start with the “system” and let the data be your guide.

Systems thinking is a fundamental thought process for implementing Lean. Yet most of us are never trained in systems thinking. In systems thinking we learn everything is connected and to look for the systemic cycles of cause and effect versus, just looking at it as a linear relationship. So part of every implementation or kaizen is taking a step back to look at the overall system and identifying the systemic changes that may be necessary.

3. How can we make it run like an assembly line and eliminate batching?

This was a key principle for me in healthcare. There is batching everywhere, in every industry and every process. We must eliminate it and strive to implement one-piece flow wherever possible.

4. Safety: Would I let a family member do the task?

We like to tell our teammates that we would like to see them leave the same way they came in to work, i.e., with all their fingers, toes, eyesight, etc. We must mistake-proof this mentality wherever possible and work to eliminate the need for personal protective equipment (PPE)

5. Do you know what you don’t know?

You must learn to continually ask yourself this question. So often we think we know but find out we really don’t know.

6. Quality: Never pass on a bad part or bad information. Do you know how to check?

Ask yourself this question whenever following a part, information step, or patient through the process.

7. Focus on the process to get the result: Do the right thing regardless of the ROI. Don’t let perfect get in the way of good.

This is a fundamental paradigm shift for every company. But think about it. If every process was optimized, what would stand in our way of achieving great results?

8. Standardize everything (to the extent it makes sense).

Imagine what life would be like without any standards. What if there was no standard for measurements, currency, etc. The only way to achieve quality is to have a standard. Our first question whenever we run into a problem anywhere in the company is “What is the standard?”

9. Implement visual management everywhere.

Without visual management you cannot manage; you can only react to problems. This leads to firefighting, which becomes a systemic problem. We find many companies today are in need of returning to good shop-floor or department management systems.

10. Create the best possible experience for our team members.

Experience is different than satisfaction. If we create a good team-member experience and continually develop the team members, it will be an enabler for a great customer experience. This concept engages people and demonstrates respect for people, which is an enabler for high-performing teams.

Why Are You Implementing Lean? What Problem Are You Trying to Solve?

PDSA

At the core of the BASICS model is the problem-solving method of plan‒do‒study‒act (PDSA). PDSA comes from Walter A. Shewhart and was later revised by W. Edwards Deming and the Japanese. Dr. Deming wrote his famous 14 points. Most companies still struggle with living these point today.

1. Create constancy of purpose toward improvement of product and service, with the aim to become competitive, stay in business, and to provide jobs.

2. Adopt the new philosophy. We are in a new economic age. Western management must awaken to the challenge, must learn their responsibilities, and must take on leadership for change.

3. Cease dependence on inspection to achieve quality. Eliminate the need for massive inspection by building quality into the product in the first place.

4. End the practice of awarding business on the basis of a price tag. Instead, minimize total cost. Move toward a single supplier for any one item, on a long-term relationship of loyalty and trust.

5. Improve constantly and forever the system of production and service, to improve quality and productivity and thus constantly decrease costs.

6. Institute training on the job.

7. Institute leadership. The aim of supervision should be to help people and machines and gadgets do a better job. Supervision of management is in need of overhaul, as well as supervision of production workers.

8. Drive out fear, so everyone may work effectively for the company.

9. Break down barriers between departments. People in research, design, sales, and production must work as a team, in order to foresee problems of production and usage that may be encountered with the product or service.

10. Eliminate slogans, exhortations, and targets for the workforce asking for zero defects and new levels of productivity. Such exhortations only create adversarial relationships, as the bulk of the causes of low quality and low productivity belong to the system and thus lie beyond the power of the workforce.

11.

a. Eliminate work standards (quotas) on the factory floor. Substitute with leadership.

b. Eliminate management by objectives (MBO). Eliminate management by numbers and numerical goals. Instead substitute with leadership.

12.

a. Remove barriers that rob the hourly worker of his/her right to pride of workmanship. The responsibility of supervisors must be changed from sheer numbers to quality.

b. Remove barriers that rob people in management and in engineering of their right to pride of workmanship. This means abolishment of the annual or merit rating and of MBO.

13. Institute a vigorous program of education and self-improvement.

14. Put everybody in the company to work to accomplish the transformation. The transformation is everybody’s job.

Deming’s 14 points embody problem-solving and the PDSA methodology (Figure 1.1). It is important to note that PDSA always starts with study. This is because you are assessing a problem after a plan, and action was already put in place. The outcome of the act of checking results in the discovery of a new gap from the A3. An A3 is a single sheet of paper, which we use to describe the story of how we solved a problem (Figure 1.2). An A3 can be used for not only problem-solving, but also deviation from the standard analysis, proposals, project status updates, i.e., new-product development, engineering design briefs, and more.

Figure 1.1 Foundation and history of the PDSA Cycle. (Source: Ronald Moen, Associates in Process, Improvement–Detroit (USA), [email protected], https://deming.org.)

Figure 1.2 A3 problem-solving storytelling example. (Source: Understanding A3, Durward Sobek and Art Smalley, 2008. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL; Managing to Learn, John Shook, 2008. LEI: Cambridge, MA; and Nigel Thurlow, Chief of Agile at Toyota Connected.)

The A3 report is a standardized report utilizing a storyboard format. The A3 helps one to organize one’s thoughts and involve others in the problem-solving process. It normally takes two to three years to learn to do an A3 correctly for complex problems. For simple processes, we don’t need the A3 form filled out but we do need A3/PDSA thinking. This prevents just “throwing solutions at problems.”

The Problem Statement

Engaging in a continuous improvement initiative means everyone must learn and understand how to problem-solve. Problem-solving starts with understanding and being able to write down the problem or gap. The problem statement should identify what is wrong (as compared to a standard or expectation), where and when it is occurring, the baseline or magnitude at which it is occurring and what it is costing me.* Once that is done, then the objective statement can be written as follows:

Improve some METRIC from some BASELINE level to some GOAL, by some TIME FRAME, to achieve some BENEFIT, and improve upon some CORPORATE GOAL or OBJECTIVE.

Set the Target Condition

As discussed, earlier the gap can come from anywhere. Once we define the gap we need to set a target. In some cases, management may set the new improvement target in their strategic plan or we find a need (mandated or innate) to do something better than it is today. We may solicit people’s ideas, whether it be from an employee, customer, supplier, patient, etc. The idea is a target from which one can infer there must be a gap in the process.

The target should have a desired outcome and should also have a designated time frame. The target provides a framework against which to measure your progress. This target should be realistic and may take anywhere from two seconds to years to realize.

Root-Cause Thinking

Once we identify the gap we need to figure out why there is a gap. For this we use something called “root-cause analysis” or “A3” thinking.

When we are faced with a new problem, our first step should be to take a step back and look at the entire system that is at work. Ask yourself the following question: Is the person at fault or is it the system, which the person is a part of, at fault?

■ Step 1 Analyze the problem, identify all the symptoms. We call these point causes.

■ Step 2 Find the root cause or causes for each of the point causes. In some cases, one root cause may solve several point causes or there could be multiple root causes tied to one point cause.

■ Rule 1 Fixing the symptom just manages the problem.

■ Rule 2 Blame gets in the way of finding the real problem.

■ Rule 3 Poka yoke to make sure the problem never comes back.

■ Rule 4 If you can’t prevent it, inspect it 100% by machine or sensor.

Do You Know What You Don’t Know?*

We utilize the operators’ talent and experience in every step of our improvement process methodology. However, many times we hear the saying: “The operators are the experts.” This may be true for the majority of the time, but not always. Operators only know what they know, based on how they were trained and/or who trained them. Sometimes they don’t know or understand everything the machine can do or what the final product looks like or how it works. We have created the following diagram. which divides knowledge into four quadrants (see Figure 1.3):

Figure 1.3 The four quadrants—Do you know what you don’t know. (Source: BIG Training Materials.)

1. You know you know: The meaning behind this one is obvious.

2. You know you don’t know: The meaning behind this one is obvious.

3. You don’t know you know: Many times, we realize we knew something, which at first, we did not think we knew. For instance, many times we do Lean things without realizing it, or sometimes, just thinking about a problem, we can logically sort it out.

4. You don’t know you don’t know: This is the most dangerous quadrant. Many times, we think we know things, which we really don’t. We call this knowing enough to be dangerous. The other interpretation is we don’t know what we don’t know. It behooves us to find an expert or continue to dig and research a problem, so we get to a point of knowing what there is to know.

Those with some Lean knowledge can sometimes be more destructive than those with none at all. One of the big obstacles with Lean is discovering, or helping others to discover, what they do not know they did not know.

At every company, when we start drilling down into processes and equipment knowledge, etc., we find people don’t really know the process or why they do what they do. When we ask how the machine works they can’t answer the questions. Then when we ask about machine manuals, they don’t know where they are stored.

For example, at a company in China, we asked them what the static-value readout on an electrostatic painting machine meant and why they recorded it every two hours. They were having a lot of quality issues with the machine. To make a really long story short, no one knew, not even the process engineers. It turns out they were constantly setting this value to some arbitrary number that someone thought in the past was the right number. It turns out the value should have never been changed once it was set. In addition, the length of the hoses from the paint to the machine played a role in the static value. Over time, maintenance was moving the equipment and would extend the hoses, which then changed the static value of the paint.

In another case, quality shut down a machine and rejected all the parts from a day’s production because the torque angle reading wasn’t good. When we asked what a torque angle was, the quality manager didn’t know. When we asked how she knew it wasn’t good, she said it was because the manufacturer of the control device told her it was not a good number. Upon further investigation we found that, at the time, the data in the report was erroneous.

Before you can start to problem-solve, the first question you have to always ask yourself is, do you know what you don’t know?

Know How versus Know Why

How often have you had a problem where you just went and fixed several things all at once, and suddenly, it works? But which thing fixed it? Alternatively, when we have a problem with testing equipment on the shop floor, we tap it (or hit it with a hammer), and it works. Sometimes we know how to fix things, but we do not know why. Eventually the tapping does not work anymore. We must learn the know why in addition to the know how to truly fix the root causes of problems.

________________

* Eighty to ninety percent of our past clients on average have sustained their Lean programs at some level over the past 20 years. Many of their examples are in The Lean Practitioner’s Field Book, Protzman, Whiton, Kerpchar, Grounds, Lewandowski, Stenberg, 2017, CRC Press. In one client this methodology has been consistently outperforming WCM being used in some of their other plants.

* The term study does not mean analysis paralysis. Back in 1996, during a Shingijutsu point kaizen event at Hitachi in Japan, Charlie Protzman learned from his sensei that the Japanese approach is always to study major changes and reach consensus (nemawashi) prior to implementation. This was not taught to Charlie at AlliedSignal during five-day point kaizen events at that time by Shingijutsu or TBM.

† Bumping lines are based on baton-zone line balancing techniques that we have been working on perfecting over 20 years. We normally see a 10%–30% increase in productivity converting from station balancing to bumping.

‡ Leveraging Lean in Healthcare, Protzman, Mayzell, Kerpchar, 2011. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL.

* The Goal, Eli Goldratt, 1984. New York: Gower Publishing.

* We never lay off full-time people at companies when we implement Lean. We use attrition or in some cases early retirement. In this case we reduced 16 people because they were temporary workers, so the company saw immediate bottom-line results.

* Contributed by Jane Fitzpatrick, Executive Consultant, Success Staging International, LLC.

* The sayings, “Do you know what you don’t know?” and “Do you know how to check?”, are credited to Danilo Bruno Franco, Operation Director of MT China, ITT High Precision Manufactured Products (Wuxi) Co., Ltd.