ACTIVITY I.A AND I.B: TASK DELIVERABLES

- I.A.1:

A project briefing has been obtained, shared, and agreed to by all key leaders.

- I.A.2:

Change leadership roles have been defined, and the change effort has been staffed with qualified people.

- I.A.3:

Effective working relationships have been established among all change leaders, and between all of the change leaders and change consultants.

- I.A.4:

Your project community has been identified and mobilized to support the change.

- I.A.5:

Your Phase I roadmap has been determined.

- I.B.1:

The process for creating your case for change is clear and has been staffed appropriately.

- I.B.2:

The drivers of your change have been determined.

- I.B.3:

The type of change has been clarified.

- I.B.4:

Leverage points for making the change have been identified.

- I.B.5:

An initial analysis of the organizational and human impacts of the transformation has been done.

- I.B.6:

The target groups of the change have been identified, and the scope of change is clear.

- I.B.7:

The degree of urgency for making the change has been assessed.

- I.B.8:

Your initial desired outcomes for the change have been determined, and the complete case for change has been prepared for communication.

The process of change actually begins the moment a person or group recognizes that there is a reason to alter how the organization and its people operate. This awareness triggers a decision process, ending in the leaders agreeing to proceed. By the time leaders decide to formally mobilize a change effort, work has already begun and information has surfaced that will affect how the leaders start up the effort. Phase I is designed for leaders to clarify where the effort is, what they are trying to accomplish, and how best to get it launched. They need to understand what is known, who is doing what, and how far along the work has progressed. Early speed and effectiveness depend on the leaders being as aware, aligned, and informed as possible.

The overall purpose of Phase I, covered in Chapters One through Four, is for the leaders of the change to establish a conscious, shared intention and strategy for a successful transformation and to prepare to lead the effort through the following:

Clarifying change leadership roles and the status of the change effort, and staffing the effort with the right people

Creating a clear case for change and determining their initial desired outcomes to use to inform and compel people to support the change

Assessing the organization's readiness and capacity to take on and succeed in the effort given everything else going on

Strengthening leaders' capability—individually and collectively—to understand, commit to, and model the behaviors and approaches required to lead this change successfully

Clarifying the overall change strategy

Designing the optimal conditions and structures for supporting the change strategy to be successful

These efforts represent the six activities of Phase I. This chapter covers the first two activities, Start Up and Staff Change Effort and Create Case for Change and Determine Initial Desired Outcomes. Before we address the work of these two activities, let's start the action where it actually begins, with the first notion of the need for change.

Wake-up calls are "aha moments," awareness of an opportunity to be pursued or a threat to be removed. They can surface anywhere in the organization, at any level. At times, there is grass-roots awareness of the need long before executives take notice. However, for an organization-wide transformation to mobilize, the leaders of the organization affected must ultimately hear the signal clearly enough to warrant attention and discussion, if not action. In change-resistant organizations, executives typically do not get or heed wake-up calls until the signals become so painful and dangerous that they threaten the organization's very survival.

The wake-up call may come in the form of a dramatic event, such as the competition beating you to market with a similar or better product; or it may be the accumulation of many small indicators that finally culminate in a loud and meaningful message. Examples of the latter include loss of market share, new technological advancements in your industry, mergers of your key competitors, the required closure of a once valuable factory, the initiation of a hostile unionization effort, or an increase in turnover of critical talent.

At this very early stage in the transformation, it is important to identify and understand what wake-up calls exist, what they mean, and what is being done with them by those in position to initiate a change effort. The mindset of the leaders has a major impact on the meaning they make of the information in the wake-up call. If the leaders are conscious and open to learning and changing, they will deal with the wake-up call differently than if they are not.

If you are consulting to the change, your initial responsibility is to assist leaders to acknowledge and respond to their wake-up calls in depth. This is the first moment of truth in the change effort; it can mean the difference between a reactive, superficial change and one that is conscious, purposeful, and able to achieve breakthrough results.

Let's assume that, at some point, the leaders receive the right signals and have acknowledged the need to change. They will automatically create an initial case for change and scope in their minds. These informal impressions will be used later as the starting point for designing the official case for change. After the leaders have committed to launch a change effort, the process is underway, officially beginning Phase I.

Establishing clear foundations for a successful change effort from the beginning increases the organization's likelihood of success. Phase I and its six activities accomplish the majority of this work. Many of the tasks of these activities can be done in parallel.

Phase I is critical work for the leaders. It covers 50 to 60 percent of the decisions that will inform your change strategy and plan. It does not take that same percentage of time, but it requires that amount of upfront decision making. The leaders cannot delegate this work, although other people can be involved to help lay the groundwork for the change leaders.

Remember the television commercial where a car repairman removes himself from under the hood of a car and says to the viewer, "Well, you can pay me now, or you can pay me later." He is referring to the fact that work must be done. You can do it now, or you can do it later; but you cannot skip it. Doing this required work upfront will undoubtedly be easier and less costly than neglecting it and dealing with the problems its absence creates downstream. In our experience, conscious leadership attention to the work of Phase I is the most powerful of all change acceleration strategies. It models the principle "Go slow to go fast" and is well worth the time and effort.

After the leaders decide to formally initiate their change process, it is imperative to gather and coalesce all of the existing information and opinion about the effort. The leaders need a clear picture of what is known, who has been doing what, and what the current reactions are. Without this, attempting to lead the change can be like herding cats. They need this early project briefing to ensure alignment, leverage progress, and minimize surprises.

Briefing data usually reveals whether key stakeholders, including the leaders, see the change effort through the same set of lenses or whether there are potentially confusing or conflicting discrepancies in people's perceptions. How people are talking about the change effort at this early date can be a significant predictor of how well it will be received after it gets underway. And, if leaders are not aligned, they will not be able to lead the effort effectively. Their alignment is essential.

The second task in this activity is to determine how the transformation will be led—who is sponsoring the effort, who is designing and leading the change strategy and process design, and who is involved in various other ways. Clear roles and responsibilities are needed for all of the change leaders to minimize redundancy and ensure full coverage of change leadership responsibilities and decisions.

Because taking on a change leadership role is usually considered an addition to one's existing duties, there are two predictable issues in staffing. The first is when these roles are assigned to people who have the most available time. Caution! Roles should be given to the people who are the most competent and best positioned to successfully lead the effort. These selections must be very strategic because your effort will either be enhanced or encumbered by these staffing selections. The second issue is that your best people are already over-committed and cannot give the change leadership role the time and attention it needs. If your best people are that busy, then you must ask yourself whether their current activities are more important than achieving the outcomes of the change. If these people are the right leaders for the change, they must free up the time to fulfill their role adequately. "Lip service" will not work.

The following sidebar presents a list of six typical change leadership roles and their deliverables. You can use all of them as described, or you may tailor them to fit the magnitude of your change effort and the resources available for it. To tailor the roles, you can use different titles and determine expanded, reduced, or different responsibilities and deliverables for each role.

We have labeled the role of the person in charge of planning the change effort as the change process leader, rather than change project manager. This title conveys the required shift from project-oriented thinking to process thinking, as described in Beyond Change Management, and emphasizes that the person in this role is responsible for designing and overseeing the transformational change strategy and the transformational change process in ways that make the possibility for breakthrough results most likely. This person may provide input to the content of the change, but the priority of this role is to shape how the change is led, designed, implemented, and course-corrected throughout.

The change process leader should be selected not only for the respect he or she commands from the line organization but also for three other critical competencies—the ability to demonstrate conscious process thinking and design skills, being sophisticated about dealing with the human dynamics of change, including culture, and having a facilitative (versus controlling) change leadership style. In addition, the more dedicated this person is to personal development and building awareness in nonthreatening ways, the better, for all the reasons discussed in Beyond Change Management. Change process leaders stuck in the autopilot, controlling, need to be "right," or project thinking modes will severely limit the probability of a successful transformation. This role works best when filled by a leader capable of working with all of the dimensions of the Conscious Change Leader Accountability Model.

One more note of caution: We frequently find that the individuals named to this critical role are the primary content experts, such as the IT guru in charge of implementing a new technology system, or worse yet, the external IT content consultant. This is extremely dangerous! The more invested the person is in a particular content outcome of the change, the less effective—or more complicated—his or her influence will be on the process of change and understanding the intricate people and cultural issues. More often than not, these people are not knowledgeable about the process or people dynamics—they are the protective owners of the content. Because there are so many process and people issues that IT implementations trigger, an objective change process leader is required—an internal person who understands how the organization operates. This role can then make sure that the content expertise of the IT guru is used in the right ways in the right tasks to produce the best content outcome for the change.

The most current example of this is in the healthcare space, for all hospital systems implementing electronic health records (EHRs). The vendors that offer the IT solutions to this critical change in healthcare are typically the least able to perceive and influence the organization's unique cultural, mindset, and behavioral requirements that a successful EHR implementation demands. EHR implementations are transformational changes—they have a direct and heavy impact on the culture, relationships, communications, and emotional needs of physicians, nurses, and support staff. They need an internal, culturally smart change process leader to shape the strategy and process plan, meet the people needs that inevitably surface, and work closely with the EHR vendor and internal IT experts when their knowledge is required.

We have experienced one creative way of dealing with the requirements of the change process leader role when an IT or other content expertise is critical to a successful outcome. It is to create a "project/process" partnership between an individual who has the technical or business expertise and a consultant with process design, people, culture, and organization development expertise. The benefit of this scenario is that the technical leader learns how to design a complex change process, and the consultant learns how to make the process relevant and timely to the business and workable for the people who must make the change happen on the ground. This joint strategy requires that the two leads have clearly defined "decision rights" and work in true partnership. Its cost is that it requires the focused attention of two people who must regularly share data and perceptions and work closely on behalf of achieving a sustainable outcome.

After change leadership roles have been defined and staffed, a common dynamic that surfaces is the confusion or tension created when leaders are asked to wear two very distinct hats—a functional executive hat and a change leadership hat. Most often, the functional hat takes precedence because it is most familiar and immediate. Plus, leaders' compensation is often tied only to their functional performance. Without support to balance leaders' drive to keep the business running and to change it, this conflict can sandbag the change effort before it gets off the ground.

Under normal circumstances, leaders' tendency to take care of daily crises in their functional organizations first is a good thing. However, when an organization is undergoing major transformation, the functional leader mindset is not sufficient. Change leaders must focus on doing what is good for the overall organization as it transforms while keeping it operational, especially at start-up. There is no formula for the percentage of time a leader will spend wearing each hat. We do know, however, that keeping full-time functional responsibilities without making real space for change leadership duties is a formula for failure. Therefore, you will need to set clear priorities and expectations for how and when the leaders should be wearing each hat, and how much time they will need to give to their change responsibilities. The resolution requires a shift of both mindset and behavior because there is only so much time available for both roles. Make the change focus a conscious one!

Ensuring that the right people are in key change leadership roles and that core responsibilities are fully covered is essential to mobilizing the quality of leadership required for conscious transformation. Our definition of "right people" here means the best match of mindset, behavior, expertise, leadership style, and time with the magnitude and type of change you are facing.

An exploration of your change leadership roles may reveal that the wrong people are in key roles. This task is an opportunity to correct your change leader selection and role expectations. Although this can be politically ticklish, making these changes now is far less costly than doing it later. You will have another opportunity to do this when you confirm your governance structure for leading the change in Task I.E.3.

Building and sustaining effective working relationships is an important condition for success. When people take on special change leadership roles, it is essential to clarify the working relationships among them and with their peers who retain existing functional roles. Too often, old political struggles will surface and hinder the change leaders from doing what the change effort requires. By addressing and clearing up past history, conflicts or political dynamics, the leaders ensure the cleanest, clearest leadership thinking and behavior to support the overall transformation. Having the leaders model the healing of broken relationships and the creation of effective partnerships is a powerful cultural intervention, one that is absolutely required to make your change effort expedient and to produce breakthrough results.

When key change leadership roles, such as the change process leader or the top change consultants, are filled by people from lower levels in the organization, you must re-establish effective working relationships among all of the change leaders and the executives. Everyone who has a key role must be clear about who has responsibility and authority to do what so that everyone can pull in the same direction. It is especially critical that people from lower in the hierarchy be given the authority they need to succeed in their new roles.

The relationship between the executive team running the business and the change leadership team changing it has to be crystal clear. The business must continue to operate effectively during the transformation, and it must also be enabled to change so that it can better serve its customers' new needs. This requires negotiating clear decision authority and responsibilities between these two teams. Make the predictable tension between these teams overt and clarify how both teams can best serve the overall good of the organization. Organization development consultants can assist with this work, which should begin when the change leadership team is established and be revisited periodically, or when issues surface throughout the transformation.

Because most enterprise-wide transformations use multiple external consultants, make sure that all consultants know who is responsible for what and how to work among them and with in-house resources to do what is best for the organization, versus their own individual agendas. Set the expectation for addressing the quality and effectiveness of their working relationships in advance, and then hold them to it.

It is important to be clear about whose realities the change effort is affecting and who needs to be involved in some way. Who has a vested interest in it producing its results? Who has something to offer it—knowledge, skill, resources? Who is going to be seriously impacted by it? Whose voices should you be seeking out and listening to as you plan it? At start-up, identify everyone—internally and externally—who has a stake in the effort and is engaged in or affected by it. This identification will provide you an easy reference for thinking through various stakeholder needs as you shape your change strategy, process plan, communications, and engagement strategy. It will also help identify the critical mass of support required for the transformation to succeed.

Some change management approaches refer to this exercise as building a "stakeholder map," which they use to identify resisters to the change. We call this group the "project community," preferring this language to convey the intention of this group to share a common vision of the change and to work together for the collective good of the organization, which provides much more use than just resistance-mapping. Figure 1.1 shows a sample project community map.

When you map your project community in detail, consider the categories of people to include: those with knowledge, skill, resources or influence to offer; those who need to be on board politically or emotionally, or buy in to the change to implement it; and those who will be impacted by it but not involved in execution, such as partners, vendors, customers or patients, or other departments dependent on what you are doing.

Note: Solid lines represent direct reporting relationships, and dotted lines indicate influence and/or partnership or cross-boundary relationships.

Your project community map should graphically reveal the relationships among its members. This will enable you to leverage these relationships strategically—and politically—throughout the change process. You may also want to identify any relationships within the community that need improvement because you will be counting on these relationships to function effectively to support the overall transformation. Use this information as input to Task I.A.3, Create Optional Working Relationships.

You can work with your project community in many ways—in person, by e-mail, or as an electronic discussion community. Your primary intention for the community is to create the conditions among all of the members to support the transformation actively as it unfolds. We are not advocating that you make this group into a formal structure. You will likely have greater impact by allowing it to operate organically, working with parts of it as your change process requires. Your strategies for this group may include the following:

Keeping these people informed of the status of the change effort; as references to help shape your change communication plans

Assigning them key roles in major change activities or events

Establishing shared expectations for how they can add value to the effort; working with them to create a critical mass of support for the vision and desired state

Shaping your engagement strategy over the course of the change process; interviewing appropriate members to gather pertinent input or using them as sounding board advisors on various strategic, operational, or cultural choice points during the transformation

Identifying resistance and political dynamics in advance

Training them in the unique requirements of your desired culture, mindset, and ways of relating

Positioning them as change advocates, models of new behavior, information generators, and so on

Exhibit 1.1 presents a worksheet to assist with identifying your project community.

Now that you are clear about who is doing what and what the current status of the change effort is, you can proceed with the important work of creating your official case for change.

Phase I of your change effort is extremely important to a successful start-up and requires a plan of its own. This task creates your roadmap for this work. At the end of Phase I, you will create a roadmap for Phases II through V. In Phase V, you will develop your Implementation Master Plan, which will be your roadmap for the remaining execution of your change effort.

In planning your Phase I roadmap, only select the tasks that you deem essential from each of the activities in this phase. Consider having your change leadership team review the Phase I tasks in their entirety, or from the CLR Critical Path offered in Chapter Fourteen, for general understanding, and then decide which they need to invest time and resources to complete. The next three chapters discuss the remaining work of Phase I.

No one, leader or employee, will give heart and soul to such a complex and challenging effort as transformation unless he or she understands why the change is necessary and what benefit it promises—personally and organizationally. This activity answers the basic questions: "Why transform?" "What needs to transform?" and "What outcomes do we want from this transformation?" "What is 'in game' or 'out of game'?" Frequently, people have many different views of why change is needed, what is driving it, and how big it is. Until your desired outcomes are clear, people will not know why they should invest the effort it will take; until they do, they will not support it. Creating your case for change and determining the results you want from it creates a common view for the change leaders and gives their stakeholders meaning, direction, and energy for aligned action. Without a clear case for change, the transformation will lack relevance for employees, causing resistance, confusion, and insecurity. The case for change includes the following:

Why the transformation is needed

What is driving this change

Type of change

Leverage points for change

Initial impacts on the organization and its people

Target groups

Scope of change

Urgency for the change

In addition, this task clarifies your initial desired outcomes for the change.

Although we have positioned this work as a part of leader preparation for the transformation, many other people may be involved in shaping the case for change and its outcomes. The marketplace, as the primary driver of the transformation, dictates the content focus of the case for change. Marketplace requirements for success can be sought by anyone who has a perspective on what your customers need and your competitors are doing. When front-line employees and middle managers participate in creating the case for change, they add credibility to the assessment of need, leverage points for transformation, and impacts. Their participation is an enormous catalyst for their understanding and commitment. No matter who generates the data for the case, we believe the leaders are responsible for putting all of this information into a clear picture that they agree with and will communicate to the organization during Phase II.

The information for your case for change may already have been generated through the organization's business strategy efforts. If so, take your exploration of the business strategy to the next level of specificity: How does the strategy require the organization to change? Use the business strategy as input to the tasks of this activity to ensure that you have a complete picture and that your case for change and your business strategy are aligned. If they exist, your case for change can also identify boundary conditions—what is okay to change, and what must stay the same. Boundary conditions may be shaped by a number of factors, such as (1) the leaders' expectations for the vision or desired outcome of the change, (2) pre-existing conditions such as strategic business imperatives or political dynamics, (3) risk mitigation needs, (4) the organization's current state of performance or financial condition, or (5) any other driving force affecting the situation. Your case for change will be strengthened by clarifying your desired outcomes for this effort—what you need to produce going forward and/or what breakthrough results you are striving to create. The statement of your outcomes should also include the benefits your organization will reap and a picture or definition of success. In simple terms, this activity describes the cause and effect of the change—what is causing it to happen and what will be achieved when it has occurred successfully!

Who builds the case for change, and how is it best produced? Who should be involved in defining your desired outcomes, the vision, and boundary conditions for the change? Your decision criteria for these questions should include: (1) people who have a big-picture understanding of the systemic and environmental dynamics driving the need for change; (2) people who understand the need for a new culture and mindset; (3) the level of urgency you face; (4) the degree to which your case and vision have already been formulated by your business strategy; and (5) people's content expertise in the areas within the predicted scope of your transformation.

Design your process for creating the case and your desired outcomes by reviewing all of the tasks of this activity and then determining how to accomplish them and the timeframe for doing so.

As a change leader or consultant, you must determine the catalysts driving the changes in your organization to design an effective case for change and change strategy. Beyond Change Management introduces seven drivers of change which, taken together, expand leaders' typical view of the scope of change. All seven drivers must be addressed to accurately scope your change effort and plan its rollout strategy—especially if it is transformational. The Drivers of Change Model is shown in Figure I.1 in the Introduction to this book, and the following sidebar briefly defines each driver. Each provides essential data for the determination of what must change in the organization and why. They might also inform what must not change. Remember, explore all seven drivers; do not stop at organizational imperatives. A full scope for transformation must include culture, behavior, and mindset.

Keep in mind that all seven drivers of change must be clarified to understand the full scope of your change. Your responses to them can tell a story, making your full case and scope easy to understand. Your story should include what will be required of leaders and managers to model and mobilize change in themselves and the organization.

Exhibit 1.2 provides a worksheet to assess what is driving your change. Use your responses as input to the scope of your change and case for change story.

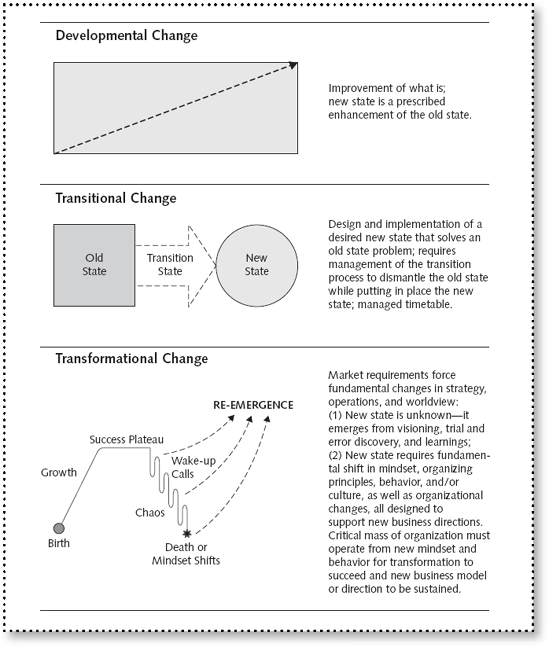

The drivers of your change reveal the primary type of change you are leading—developmental, transitional, or transformational. The more culture, behavior, and mindset change required, the more it is transformational. In our writing, we frequently refer to your change effort as transformational. That is because the CLR is designed to serve the unique needs of transformation, as well as the other types of change. Because your change effort may not actually be transformational, you will still need to determine the right type of change you are leading.

The type of change has direct implications for the change strategy and leadership your effort requires. The consequences of not defining the type of change accurately can create costly havoc, or failure, for the effort. Too often, when leaders learn of the three types, they choose developmental or transitional change because these types appear to be easier to manage. If your change is actually transformational, however, you cannot change that fact by calling it something else. If it is transformation, it is transformation; you will still need to build a change strategy and plan that fits transformation. As a conscious change leader, your challenge is to determine the actual type of change occurring and plan from there. Figure 1.2 graphically portrays the three types, discussed in depth in Beyond Change Management.

Although you may have multiple types of change present within your overall effort or your composite initiatives, one type is always primary. That is the one that will most influence the design of your change strategy. For instance, you may need to develop better marketing skills and systems (developmental change), and you may need to consolidate several functions to improve efficiencies (transitional change), but the primary change is a radical transformation of your business model to e-commerce. Such a change is transformational because it calls for a significant shift in direction and requires major culture, behavior, and mindset change in your leaders and people.

Most change efforts have one or two critical things that must change; this work will prompt or catalyze shifts in other aspects of the organization. These few things are called leverage points for change. Frequently, they are the content focus of the change. For instance, your leverage point may be to employ a human resources information system to gather and integrate all data about every employee, for every HR need. That is a leverage point to process large amounts of HR data for policy and performance purposes, and to streamline and standardize all HR transactions across a complex or dispersed organization. Or, a different leverage point is to consolidate supply chain and purchasing across an entire system so that costs and efficiencies can be more vigorously managed. A third example is to change the culture of the organization to be more entrepreneurial, more team-based, or co-creative. These types of cultures are essential to innovation, efficiencies, and the level of cross-boundary work required to serve diverse customer or patient needs. For each of your leverage points, make sure that all change leaders agree on its primary importance and the benefits it will produce toward your desired outcomes.

These examples name the primary work that will catalyze needed changes. They do not, however, define the total scope of your change. That comes from several of the tasks in this activity, culminating in a full scope of change in Task I.B.6. Your case for change, however, will feature your leverage points to help clarify the purpose and focus of the transformation.

As you become clearer about what your change effort's scope entails, it is important to identify the types of impacts that making this change will create throughout the organization. The earlier in your change you clarify those impacts, the better your planning will be. At this point in the process, an assessment of impacts can only be done at a generalized level. When you have designed the actual future state, you will be able to do a more thorough analysis. That is the purpose of Phase V. For now, this general assessment focuses the leaders' attention on both the business/organizational elements and the personal/cultural impacts. A general impact analysis at this stage may also reveal impacts that challenge the leaders' expectations for what needs to stay the same.

A helpful tool to perform this assessment, the Initial Impact Analysis Audit, is provided in Exhibit 1.3. This tool lists many typical impact areas affected by change in the organization. The Initial Impact Analysis Audit is a powerful way to expand the change leaders' view of the amount of attention, planning, time, and resources the change will require. It is designed to create a systems view of the organization and the transformation. These topics will tell you, at a high level, how broad and how deep the impact of making the transformation will go. This information, in addition to your determination of the drivers of change and your leverage points, is critical to understanding what your change strategy needs to address for the transformation to succeed. This information will be used as input to determining the scope of the change and may also inform your decision about needed capacity for change.

To fill in the Initial Impact Analysis Audit, consider the change effort as you currently understand it. Review each item in the tool, checking it if it will be affected by your change effort during design or rollout. Each item checked requires more detailed planning and attention as a part of Phases V and VI in your change process plan. For now, noting the areas requiring more focus will help you clarify your scope of change.

Your case for change must accurately identify the target groups of the transformation as well as the scope of change required in the organization. Targets are the groups and people who will be directly impacted by the change or who are essential in carrying it out. If you created a Project Community map in Task I.A.4, you have likely identified your target groups. It is essential that you consider the various needs of your target groups as you plan your change, your communications, and your engagement strategies.

Scope is the breadth and depth of the change effort, including your target groups and initiatives. It determines what you will pay attention to and plan for. One of the most common mistakes leaders make in leading change is to misdiagnose its scope, typically making it too narrow. If it is too limited, repercussions will be occurring outside of your view of things, creating all kinds of unpleasant surprises. If your scope is not accurate, you may be missing key leverage points for getting the change to happen or expending energy on the wrong things. The classic misperception is to define scope in exclusively organizational, technical, or business terms, neglecting the cultural and people changes required for success. For transformation to work, scope must attend to all of the change required. Both the Drivers of Change Model and the Initial Impact Analysis Audit outline both types of initiatives required in scope. Use them as input to your scope.

Another output from your drivers of change is the conscious determination of the degree of urgency for making the transformation. The degree of urgency you assign at this point in your change effort will set the stage for success or failure, so being aware of what is accurate is essential. Being overly urgent will create panic and unfocused action. Low urgency will create complacency. What is really true about the urgency of your change?

A common error in leading transformation is the automatic assumption that the change needs to occur faster than is humanly possible. Our society assumes urgency; we live in the face of the tidal wave of speed. Urgency, in and of itself, is not a bad thing. It is an important motivator for focused action. However, when leading transformation, a realistic sense of urgency is essential. It is one of the key determinants of how well the organization will respond to the change.

Keep in mind that urgency is not the same thing as your timetable. Wanting speed is not the same as the marketplace absolutely dictating a deadline. Employees will understand a true need for speed but will disregard fabricated urgency and label it one more reason executives cannot be trusted to tell the truth. Don't make this mistake. Executives who unconsciously push transformation into unrealistic timetables without thinking through their internal motivations or the state of their people usually cost the organization in damaged morale, lost productivity, or impaired quality, all of which inevitably take more time to repair.

This task helps you consider the factors influencing your level of urgency, which is the first step in determining the timing and pace of your change.

The sense of urgency you establish here will become input to Task I.E.12. In that task, you will identify your critical milestones and general timeline as part of developing your change strategy.

Then, in Phase VI, Plan and Organize for Implementation, you will be able to develop a more informed timeline. At that point in the change process, your work will be based on a detailed impact analysis of external factors (environment, marketplace, and organization), internal factors (culture, time for skill development, personal change, and people's capacity), and the actions required to resolve all impact issues. Then the real work of the change, compiled into your Implementation Master Plan, can better indicate how long the effort will take if done well. However, at this early Phase I stage, the change leaders can only guess at the timetable, using their initial assessment of the scope of change and their impression of people's capacity to do what is required. Therefore, in communicating time pressures at this early stage, it is smarter to focus on urgency and present your desired timetable only as an initial estimate.

The results of the first seven tasks of this activity produce your initial stance on why you need to make this change and what you want it to accomplish—your outcomes. You may have identified desired outcomes for any of the drivers of change as you worked on them. In addition, you will need to clarify any boundary conditions that must be respected as the change proceeds as well as your overarching outcome for the whole transformation.

Desired outcomes can take many forms. We typically see high-level aspirations that comprise a vision or set of compelling expectations. We see goals, objectives, and metrics, all of which are more concrete than aspirations. At this point, your intention is to shape a motivational vision for this transformation. If you have enough data to get more specific, you can also do that. If your change effort is primarily cultural, make sure to develop your outcomes in terms that speak to the positive effect of the new culture—what it is intended to enable in the organization. Use this information to provide the workforce with the motivation, rationale, and inspiration for taking on this effort, or provide the information as input to the stakeholders you want to engage in a larger visioning process. In Task I.F.3, you will design your visioning strategy and establish whether it will be primarily leader-driven or participatory.

Beyond Change Management discusses five different levels of success, which are also ways of defining your desired outcomes: (1) New State Design Determined, (2) New State Design Implemented, (3) Business Outcomes Achieved, (4) Culture Transformed, and (5) Organizational Change Capability Increased. This task benefits from leaders considering what level of success they are after, because most leaders think of outcomes as only Level Three, Business Outcomes Achieved. The other levels are also outcomes, if you consciously choose them and build them into your change strategy. Each level increases the return on investment from your change.

All of the information generated in this activity forms the basis of your case for change. The earlier introduction to Activity I.B lists all of the elements of your case for change. Review them, refine the results of all of the tasks of this activity, and write your case for change. Exhibit 1.4 provides a sample case for change.

The case for change is critical input for your change strategy, which is compiled in Activity I.E. At the beginning of Phase II, you will communicate the case for change, your change strategy, and any input to your vision for the change to the organization. With this in mind, tailor your case for ease of communication, making it concise, informative, accessible, and inspirational.

You have now formed a realistic picture of the current status of the change effort and staffed its leadership. You have identified all of the stakeholders of the change and have begun to align all of the key players to support the transformation. In addition, you have clarified your initial assumptions about your case for change, desired outcomes and vision, scope, and pace of the transformation. The next chapter continues with more Phase I work, addressing the organization's level of readiness, capacity, and capability to proceed with what you are currently planning.