E

Early Bilingualism

ANNICK DE HOUWER

There are two fundamentally different ways in which children under age six become bilingual. First, children may hear two languages from birth in what is known as a bilingual first language acquisition (BFLA) setting (Meisel, 1989). BFLA children have no chronologically second language but have two first languages, Language A (LA) and Language Alpha (Lα). These typically are both spoken to them at home. Second, children who are first raised with just a single language at home (Language 1, L1) may start to regularly hear a second language (Language 2, L2) at a later age, typically in a group setting outside the home, such as a daycare center or a preschool. This is an early second language acquisition (ESLA) setting (De Houwer, 1990). BFLA settings have been found to be about three times as common as ESLA settings where the L2 is a societal language (De Houwer, 2018a).

This entry first describes major linguistic developments in BFLA and ESLA in children under the age of six (early foreign language acquisition is not discussed). After that, early child bilingualism is considered from a more applied perspective. Although there is growing interest in studying trilingualism, the bulk of the relevant studies concerns two oral languages. The little research on children growing up with an oral and a signed language suggests that early bimodal bilingual development proceeds similarly to early unimodal bilingual development, except that bimodal bilinguals may use two languages contemporaneously (Tang & Sze, 2019). The BFLA/ESLA difference also applies in bimodal bilingual settings.

Major Linguistic Developments in BFLA and ESLA

BFLA children start to regularly hear two fundamentally different ways of speaking once they are born. Infants who hear two rhythmically very different languages before they are born can distinguish between them right after birth (Byers‐Heinlein, Burns, & Werker, 2010). Infants who hear rhythmically less strongly differing languages since birth can distinguish between them by the age of 3.5 months (Molnar, Gervain, & Carreiras, 2014).

By their first birthday, BFLA children can understand words in each of their languages (Cruz‐Ferreira, 2006). There are great differences among same‐age BFLA children in how many words and phrases they understand in each of their two languages (De Houwer, Bornstein, & Putnick, 2014).

BFLA children make language‐like sounds in the first year of life, including sounds that resemble syllables. Longer repetitions of the same syllables (babbling) start to occur by 7 to 9 months (e.g., “bababa gaga”; Ronjat, 1913). It is unclear to what extent babbling reflects specific aspects of the languages children are hearing, but one BFLA child's babbling was found to reflect phonological aspects of the parental input (Andruski, Casielles, & Nathan, 2014).

Around the first birthday, BFLA children start to make sounds that remind adults of specific words (Leopold, 1939–49/1970). They do not necessarily start to say words in each of their two languages at the same age: There may be a time lag of several months between their saying a word in LA and in Lα. However, some BFLA children start saying words in each of their languages on the same day (De Houwer, 2009, p. 218).

BFLA one‐year‐olds use word‐like vocalizations in order to ask for things, comment on a state of affairs, draw someone's attention to a situation, and for many more functions (Cruz‐Ferreira, 2006). Same‐age BFLA children differ a lot from each other in the number of different words they can say, that is, produce (De Houwer et al., 2014). In the second year of life, BFLA children's production vocabulary size in LA correlates with that in Lα (Conboy & Thal, 2006). Many of the words they produce are words for the same thing in each language (translation equivalents; De Houwer et al., 2014).

BFLA children's pronunciation of early words is still quite immature, and can differ considerably from adult pronunciation. All children reverse sounds (e.g., “puck” instead of “cup”), delete some sounds (e.g., “uh” instead of “Kuh,” for German ‘cow’), or substitute sounds (e.g., “heaby” instead of “heavy”; Gut, 2000; Brulard & Carr, 2003). These phonological processes slowly give way to more adult‐like pronunciations, but no child under age six sounds completely adult‐like (De Houwer, 2009, chap. 5).

Just before their second birthday, most BFLA children are combining two words into a single utterance (e.g., “no eat,” “daddy door”; Patterson, 1998). Some children produce two‐word utterances for many months. Others use two‐word utterances for only a short time, and soon move on to saying three and four‐word utterances.

Once children start to combine more than two words they are often saying real sentences. These early sentences usually have a word order that is correct in the language they are using, and they may contain grammatical words and inflections. Soon children are on their way to forming clauses and complex sentences (De Houwer, 2009, chap. 7).

As BFLA children grow into the preschool years, they continue to expand their vocabulary, improve their pronunciation, and expand the diversity and complexity of grammatical structures. They also learn to tell connected stories. BFLA children's language use in each of their languages closely resembles that of the adults who speak these languages to them. However, young BFLA children's language use is still a fairly limited version of what adults are capable of. This gradually changes as they get older.

So far, the developments described are very similar for children growing up just with a single language, with the difference that BFLA children learn sounds and words in two languages. There is no difference between BFLA and monolingual children in the timing of major developmental milestones, like babbling, first word comprehension, or the first occurrence of word combinations. The only notable difference is that BFLA children's total word comprehension vocabulary size at age 13 months is at a level that monolinguals on average reach only 4.5 months later (De Houwer et al., 2014).

One aspect that cannot be studied in monolingual children is the relation between BFLA children's two languages. This relation has been of major interest to scholars.

On a global level, uneven development across languages is common, with one language developing faster for some or all aspects of language use than the other. Development may be so uneven that children speak just a single language. This is the case for an estimated quarter of BFLA children (De Houwer, 2007; Verdon & McLeod, 2015). Thus, hearing two languages from birth is not a guarantee for actually speaking two. This differs from a monolingual setting, where children who have no hearing problems or do not suffer from disorders known to affect language development all learn to speak the one language they are hearing.

At a more detailed level, many BFLA children appear to develop two fairly separate phonological systems, but often it is hard to decide whether young BFLA children's sounds are used in a language‐specific way. It may never be possible to fully know whether BFLA children's early phonological development is different for LA and for Lα.

Most of BFLA children's multiword utterances are unilingual, that is, they contain free morphemes from just a single language (free morphemes are words that have a referential, e.g., “read,” or grammatical, e.g., “the,” meaning). BFLA children may say unilingual utterances in each of their two languages or just in one. If free morphemes from two different languages are combined into a single utterance, the utterance is mixed. There is large variation among BFLA children in the proportion of mixed utterances they use (De Houwer, 2009). The proportion of mixed utterances also varies considerably over time within the same child. A typical characteristic of most early mixed multiword utterances is that they contain just a single noun from LA and that all the other words are in Lα.

The structure of unilingual utterances as said by BFLA children usually follows the rules of the language the free morphemes are in. That is, when a multiword utterance has free morphemes only from Language A, the word order rules and the grammatical properties of LA will be used. The same goes for Lα. The repeated finding of these facts for many different languages and many different language combinations (reviewed in De Houwer, 2009, Appendix G) gives strong support for the Separate Development Hypothesis (De Houwer, 1990), which states that BFLA children develop two distinct morphosyntactic systems. Unilingual utterances as produced by BFLA children could in most cases have been said by monolingual children acquiring each of a BFLA child's two languages as their only one.

ESLA children's language development is more variable than that of BFLA children. This is to be expected, given the different ages at which ESLA children start to learn their L2 and the different circumstances in which they learn their L2. Most studies of ESLA focus on children's L2 development rather than their L1 and concern children who first started to learn their L2 after age 3. Until they start to speak an L2, ESLA children's L1 use resembles that of monolingual and BFLA children. Once ESLA children have achieved fluency in their L2, their L1 speaking skills may continue to develop, decline, or disappear altogether (Shin, 2005). How these differences in L1 use affect development in the L2 is not known.

Studies of ESLA so far suggest that on average it takes children under age six at least two years of exposure to the L2 in an immersion‐type setting to start to be able to say nonimitated sentences in the L2 (De Houwer, 2018a). This runs counter to the common assumption that ESLA children learn their L2 very fast. Instead, many ESLA children first go through a long period in which they are just trying to make sense of what is going on in the L2 spoken around them, without attempting to speak it themselves. This is followed by first attempts to speak the L2 in formulaic utterances and single words. Gradually, the formulas are expanded into more varied sentences. Speed in learning to speak the L2 well is highly correlated with earlier levels of L1 proficiency (Winsler, Kim, & Richard, 2014).

ESLA children make mistakes when they start to build L2 sentences that are not imitations. These mistakes often arise because a particular grammatical feature such as an English plural ‐s ending was not pronounced. Children may also use incorrect grammatical features. Some errors are comparable to the ones younger children make in acquiring the same language as an LA or L1. In addition, there are different kinds of errors that show a clear influence from ESLA children's L1. Many ESLA children's early L2 utterances do not sound like those that children acquiring the same language as an LA or L1 would say (but many others do). Yet, as time goes on, ESLA children may become indistinguishable from children for whom the language is an LA or L1.

ESLA children's developing L2 phonology may be influenced by their L1 as well, and, indeed, the other way round (Hambly, Wren, McLeod, & Roulstone, 2013).

Thus, different patterns exist for different language combinations. Once again, there is a large degree of interindividual variation.

As for BFLA and monolingual children, there is great variation in ESLA children's lexical knowledge. Some children will know many words in both languages, others far more in one. Both ESLA and BFLA children may be able to discuss a particular topic only in one language. Although both BFLA and ESLA children will generally know more words in both their languages combined than monolingual children, ESLA children will start off having smaller vocabularies in the L2 than age‐matched BFLA or monolinguals children who have heard that language from birth, simply because word learning is so strongly related to learning opportunities.

When BFLA and ESLA children actually speak two languages, they may speak those languages at quite different levels. They may be much more fluent in one language than in the other, and know more words in one than in the other (uneven development, see above). With changing circumstances, the balance may change. There are also bilingual children who seem to speak each of their languages equally well. There is more and more evidence pointing to the crucial role that children's language input plays here (see Armon‐Lotem & Meir, 2019, for ESLA, and De Houwer, 2018b, for BFLA).

Like BFLA children, ESLA children may produce mixed utterances. These have similar structures in both BFLA and ESLA children. Young bilingual children easily switch between unilingual utterances in LA or L1, unilingual utterances in Lα or L2, and mixed utterances. Their switching is influenced by sociolinguistic factors, such as the interlocutor's language choice, the interlocutor's expectations, the place of interaction, the topic, and so on. Both in the fact that they easily switch, and in the fact that they usually switch for clear sociolinguistic reasons, bilingual children resemble bilingual adults right from the start (De Houwer, 2019).

Applied Aspects of Early Bilingualism

Many bilingual children live in an environment that fosters their active and proficient use of two languages. Yet many others are not that lucky. They may understand two languages, but speak only one, much to their own chagrin or that of their family members, or they may speak two languages in ways that are unsatisfactory to their environment. In addition, frictions may arise in bilingual families that are attributed to the fact of bilingualism (De Houwer, 2015).

Often, parents, teachers, and speech therapists expect child bilinguals to function at least as well as the best monolinguals in each of their languages. This is an unrealistic expectation and assumes that bilinguals are two monolinguals in one. They are not. Furthermore, it is normal for bilingual children to develop each language at a different rate. One reason for this uneven development lies in the quantity of bilingual children's language input, which is often quite different for each language. The language that children hear most will often be the language in which they are more advanced. Uneven development can lead to parents, teachers, and speech therapists being concerned about a bilingual child's development: If they look just at a bilingual child's momentarily less well‐developed language, they could sometimes get the impression that the child has a language‐learning problem. As for monolingual children, it is important to consider the totality of what bilingual children are able to do with language. This will include considering the other language they know. It is only when bilingual children are showings signs of very slow development in both of their languages that one has to start worrying: Children may be having hearing difficulties, or any other kind of physiologically or neurologically determined condition that is known to negatively affect language development. It is also possible that children are deprived of the right kind of language input in both their languages.

A persistent myth is the idea that children can learn a second language very fast. While some young children who hear another language may indeed soon be able to say a few well‐chosen words and phrases in that language, and may be able to effectively take part in informal conversations, it usually takes several years for ESLA children to master their new language, just as it does in BFLA and monolingual children, who, however, have had the benefit of hearing their language(s) since birth. Learning to speak like a six‐year‐old takes a six‐year‐old monolingual child six years of practice and taking advantage of learning opportunities. ESLA children under the age of six may develop their L2 at a rate that is faster than for BFLA and monolingual children when they first start to speak, but the evidence suggests that it still takes at least a year or two after initial regular contact with an L2 for many young ESLA children to become fluent conversational partners.

Simply put, bilingual children need the time and opportunity to learn their two languages. For parents in a bilingual setting this means that they should talk to their children as much as possible. If parents use two languages at home, they should make sure to talk a great deal to their children in both. If parents speak one language at home, and the L2 is used outside the home, the home language should be spoken very frequently. As children start to go to school, parents should try to expand children's vocabulary in the home language, so that it remains an important vehicle for communication, and so that children get the chance to continue to develop in their L1. This is important for harmonious bilingual development (De Houwer, 2015).

Many (preschool) teachers and speech therapists are concerned about early bilingualism. They often believe that early bilingualism is an impediment to learning the school language (Shin, 2005; De Houwer, 2009). Many pediatricians and parents have the idea that early child bilingualism is just not possible, or only possible for exceedingly smart children. Others believe that young bilingual children are confused and cannot get their languages straight. The existence of many proficient bilingual children is the best proof that early child bilingualism certainly is possible. Young BFLA children can speak each of their languages without noticeable systematic influence from the other, and many ESLA children can learn to speak their L2 very well indeed.

Still, negative attitudes toward early child bilingualism persist. If there are any problems for a child's bilingual development, it is these negative attitudes that frequently are to blame (Shin, 2005; De Houwer, 2009). One particularly strong and detrimental effect of negative attitudes is the frequent advice of teachers, speech therapists, and doctors to parents to stop speaking the nonsocietal language to their children. Parents often follow this ill‐conceived advice, with quite negative results: They can in many cases no longer communicate well with their children (since they may be switching to a language they hardly know), and the children are bewildered and upset that their parents all of a sudden speak another language to them; many children see this change as putting an undesirable distance between parents and themselves, and find it hard to bear. On the other hand, in cases where children have problems communicating in either language, medical personnel often place the blame on a bilingual family environment, and may advise to stop talking the minority language at home, without addressing what later may surface as the real underlying problem, for instance, deafness.

The common “professional” advice to give up speaking a particular language to a child appears to assume that having less input in a language will increase skill in another. There is no evidence to this effect. More fundamentally, the advice is morally and legally unacceptable. It goes against the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which states in Article 29, division (c), that the States parties to the Convention agree that the education of the child shall be directed to

the development of respect for the child's parents, his or her own cultural identity, language and values, for the national values of the country in which the child is living, the country from which he or she may originate, and for civilizations different from his or her own. (United Nations, 1989)

In families that stop speaking the nonsocietal language, children will effectively become monolingual.

Many children with continued and regular bilingual input will end up speaking only one language (while often understanding two, and thus continuing to be bilingual). In these children's families, parents address children in the nonsocietal language and children respond in the societal language. In some cases, family members do not consider such conversational patterns to be problematic. However, most parents in these bilingual families do find it a big problem that their children do not speak the nonsocietal home language (De Houwer, 2017). In many cases, this effectively limits communication between parents and children, and the transmission of cultural values. Parents may feel rejected by their children and ashamed. Often, as children grow up, they are sad not to be able to communicate with members of their extended family, and not to be able to function in the family's country where the language they do not speak is being used.

Why do so many children growing up in bilingual circumstances speak only one language (always the societal language) instead of the expected two? In a survey of about 2,500 bilingual families in Flanders, De Houwer (2007) traced connections between parental language use and child use of the nonsocietal language. Those bilingual families where children spoke only the societal language tended to be families where both parents used the societal language at home, and only one parent in addition used the nonsocietal language. Parents who (a) both spoke the societal as well as the nonsocietal language at home, and who (b) both spoke the nonsocietal language at home, with one parent in addition using the societal language, had much better chances of having children who spoke the two languages. Parents who only used the societal language at home had the most chance of having children who spoke two languages.

Several contributing elements can explain these findings but the most important one may be related to frequency of input: If only one parent speaks the nonsocietal language at home, but in addition that same parent also uses the societal language, there may be less input in the nonsocietal language than in families where both parents speak the nonsocietal language (in addition to one or both also speaking the societal language). Second, families where both parents speak the nonsocietal language at home may create much more of an environment conducive to using that language. After all, the family already has two members speaking it rather than just one. Parents may also be more inclined to speak the nonsocietal language with each other.

Another important factor contributing to whether bilingual children speak two languages or just one has to do with the communicative need to speak two languages rather than just one. If there is no communicative need to speak two languages, bilingual children will not do so. This communicative need is created in and through conversation. Some bilingual parents do not mind if their child speaks only one language when they start to talk. They are just happy that their infant can talk, and will respond to the child's utterances without focusing on the actual language the child spoke. They may answer a child's question in Italian with a response in German, if that is the language they usually use with their infant. These parents are using what Lanza (1997) has termed “bilingual discourse strategies”—conversational patterns that allow the use of two languages within a conversation. Other bilingual parents may be much less tolerant of the use of two languages within a conversation, and will socialize the child into using mainly one language within a stretch of discourse. These bilingual parents use what is termed “monolingual discourse strategies” (Lanza, 1997). Although so far there have not been enough studies documenting these discourse strategies and their possible effect on children's language use, it is likely that, if parents use mainly bilingual discourse strategies and allow the child's use of Lα, children have no need for speaking LA and will become part of that large group of children raised bilingually who understand two languages but speak only one.

The importance of communicative need is also a factor in ESLA. When children hear a new L2 at preschool but have friends there that they can speak their L1 with, they will feel less of a communicative need to actually speak the new L2, and may be slower in developing any fluency in the L2. Becoming friends with children who speak the L2 will foster an ESLA child's L2 development.

There are many more important matters to mention about early child bilingualism. The most important point, however, is that bilingual children need the time and the opportunity to learn to speak each of their languages. Given sufficient time and learning opportunities, and a positive attitude from all involved toward the bilingual language learning experience, children everywhere can become fluent speakers of two languages from early on.

SEE ALSO: Bilingual and Monolingual Language Modes; Conversation Analysis and Child Language Acquisition; Crosslinguistic Influence in Second Language Acquisition; First Language Vocabulary Acquisition; Formulaic Sequences; Heritage Languages and Language Policy

References

- Andruski, J. E., Casielles, E., & Nathan, G. (2014). Is bilingual babbling language‐specific? Some evidence from a case study of Spanish–English dual acquisition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 17, 660–72.

- Armon‐Lotem, S., & Meir, N. (2019). The nature of exposure and input in early bilingualism. In A. De Houwer & L. Ortega (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of bilingualism (chap. 10). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Brulard, I., & Carr, P. (2003). French–English bilingual acquisition of phonology: One production system or two? International Journal of Bilingualism, 7(2), 177–202.

- Byers‐Heinlein, K., Burns, T. C., & Werker, J. F. (2010). The roots of bilingualism in newborns. Psychological Science, 21(3), 343–8.

- Conboy, B. T., & Thal, D. (2006). Ties between the lexicon and grammar: Cross‐sectional and longitudinal studies of bilingual toddlers. Child Development, 77, 712–35.

- Cruz‐Ferreira, M. (2006). Three is a crowd? Acquiring Portuguese in a trilingual environment. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

- De Houwer, A. (1990). The acquisition of two languages from birth: A case study. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- De Houwer, A. (2007). Parental language input patterns and children's bilingual use. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28(3), 411–24.

- De Houwer, A. (2009). Bilingual first language acquisition. Bristol, England: Multilingual Matters.

- De Houwer, A. (2015). Harmonious bilingual development: Young families' well‐being in language contact situations. International Journal of Bilingualism, 19(2), 169–84.

- De Houwer, A. (2017). Minority language parenting in Europe and children's well‐being. In N. Cabrera & B. Leyendecker (Eds.), Handbook on positive development of minority children and youth (pp. 231–46). Berlin, Germany: Springer.

- De Houwer, A. (2018a). Input, context and early child bilingualism: Implications for clinical practice. In A. Bar‐On & D. Ravid (Eds.), Handbook of communication disorders: Theoretical, empirical, and applied linguistic perspectives (pp. 599–616). Berlin, Germany: Mouton de Gruyter.

- De Houwer, A. (2018b). The role of language input environments for language outcomes and language acquisition in young bilingual children. In D. Miller, F. Bayram, J. Rothman, & L. Serratrice (Eds.), Bilingual cognition and language: The state of the science across its subfields (pp. 127–53). Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins.

- De Houwer, A. (2019). Language choice in bilingual interaction. In A. De Houwer & L. Ortega (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of bilingualism (chap. 17). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- De Houwer, A., Bornstein, M. H., & Putnick, D. L. (2014). A bilingual–monolingual comparison of young children's vocabulary size: Evidence from comprehension and production. Applied Psycholinguistics, 35(6), 1189–211.

- Gut, U. (2000). Bilingual acquisition of intonation: A study of children speaking German and English. Tübingen, Germany: Niemeyer.

- Hambly, H., Wren, Y., McLeod, S., & Roulstone, S. (2013). The influence of bilingualism on speech production: A systematic review. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 48, 1–24.

- Lanza, E. (1997). Language mixing in infant bilingualism: A sociolinguistic perspective. Oxford, England: Clarendon.

- Leopold, W. (1939–49/1970). Speech development of a bilingual child: A linguist's record. New York, NY: AMS Press.

- Meisel, J. (1989). Early differentiation of languages in bilingual children. In K. Hyltenstam & L. Obler (Eds.), Bilingualism across the lifespan: Aspects of acquisition, maturity and loss (pp. 13–40). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Molnar, M., Gervain, J., & Carreiras, M. (2014). Within‐rhythm class native language discrimination abilities of Basque‐Spanish monolingual and bilingual infants at 3.5 months of age. Infancy, 19(3), 326–37.

- Patterson, J. (1998). Expressive vocabulary development and word combinations of Spanish–English bilingual toddlers. American Journal of Speech‐Language Pathology, 7, 46–56.

- Ronjat, J. (1913). Le développement du langage observé chez un enfant bilingue. Paris, France: Champion.

- Shin, S. (2005). Developing in two languages: Korean children in America. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

- Tang, G., & Sze, F. (2019). Bilingualism and sign language research. In A. De Houwer & L. Ortega (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of bilingualism (chap. 24). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- United Nations. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. Retrieved April 24, 2019 from https://downloads.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/UNCRC_united_nations_convention_on_the_rights_of_the_child.pdf?_ga=2.195099244.153784519.1556099464-518761887.1556099464

- Verdon, S., & McLeod, S. (2015). Indigenous language learning and maintenance among young Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. International Journal of Early Childhood, 47(1), 153–70.

- Winsler, A., Kim, Y., & Richard, E. (2014). Socio‐emotional skills, behavior problems, and Spanish competence predict the acquisition of English among English language learners in poverty. Developmental Psychology, 50, 2242–54.

Suggested Readings

- Abdelilah‐Bauer, B. (2008). Le défi des enfants bilingues: Grandir et vivre en parlant plusieurs langues. Paris, France: Editions la Découverte.

- De Houwer, A. (2009). An introduction to bilingual development. Bristol, England: Multilingual Matters.

- Montanari, E. (2002). Mit zwei Sprachen groß werden: Mehrsprachige Erziehung in Familie, Kindergarten und Schule. Munich, Germany: Kösel.

- Montanari, E., Aarssen, J., Bos, P., & Wagenaar, E. (2004). Hoe kinderen meertalig opgroeien. Amsterdam, Netherlands: PlanPlan.

- Okita, T. (2002). Invisible work: Bilingualism, language choice and childrearing in intermarried families. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins.

- Serratrice, L. (2019). Becoming bilingual in early childhood. In A. De Houwer & L. Ortega (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of bilingualism (chap. 1). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

English for Academic Purposes

LYNNE FLOWERDEW

Introduction

The field of English for academic purposes (EAP) is positioned within the wider field of ESP (English for specific purposes). Figure 1 displays the two main subdivisions of ESP: EAP, the main focus here, and, to a much lesser extent, EOP (English for occupational purposes, addressing students' perceived future needs in the workplace). What sets apart EAP from general English courses, for the most part, is the focus on students' needs, which are discovered through target situation analysis (objective needs focusing on the tasks and activities students will be using English for) and present situation analysis (more subjective‐type needs attending to personal information about the learners such as previous learning experiences, and so forth, and their current level of competence).

Key debates in the literature on EAP have raised both theoretical and practical issues regarding the essential nature of EAP and its ability to target students' needs. These issues are first discussed and then followed by an overview of the five main approaches underpinning EAP pedagogy: study skills, grammar and vocabulary, discourse/genre, academic literacies, and critical EAP.

Generic or Specific Attributes in EAP?

Proponents of the “common core” hypothesis maintain that there exists a generic set of skills, linguistic structures, and vocabulary found across a range of academic texts, regardless of discipline and genre, that are transferable from one academic discipline to another. Other EAP researchers, though, most notably Hyland (2006, 2009), reject the concept of a generic skill set, such as “academic English” or “business English,” making a strong case for “specificity” on account of disciplinary variation.

Figure 1 Subdivisions of EAP (Flowerdew & Peacock, 2001, p. 12, adapted from Dudley‐Evans & St. John, 1998) © Cambridge University Press

EAP researchers from opposing camps have analyzed computerized corpus data (i.e., large databases of academic text) to support their respective positions. For example, Coxhead's (2000) corpus‐based research of vocabulary items in a 3.5 million‐word corpus composed of written academic texts drawn from the disciplines of arts, commerce, law, and science supports the “common core” hypothesis, with its extraction of common core vocabulary items forming an academic word list. However, Hyland and Tse's (2007) corpus analysis of seven key genres of academic writing (research articles, textbooks, doctoral dissertations, and so on) points to a discipline‐based specific lexical repertoire. Other ESP studies of textbooks and research articles in which word lists from specialist disciplines are compared with Coxhead's academic word list also favor sets of discipline‐specific lexis, with the majority of these studies published in English for Specific Purposes. Perhaps, in the common core debate, a key point to note is that all these studies rely on different types of corpora and use different software for analysis, so it is not surprising that the findings differ and that this area is still fraught with controversies regarding the essential nature of EAP.

It is important to note, however, that the question of specificity is not purely determined through text‐based analyses, often supported by quantitative corpus‐based evidence. It is also revealed through more qualitative, ethnographic enquiries (e.g., interviews and observations) of the context in which the discourse is socially embedded (see Paltridge, Starfield, & Tardy, 2016, for an in‐depth discussion of this ethnographic perspective). As Hyland (2002, p. 390) states: “Disciplines have different views of knowledge, different research practices, and different ways of seeing the world, and as a result, investigating the practices of those disciplines will inevitably take us into greater specificity.”

Arguments for and against implementing either generic or more specific EAP courses are summarized in Basturkmen (2010). For example, a highly specific EAP course may not be very motivating for undergraduate students, but be deemed as highly relevant by postgraduate students engaged in writing dissertations. Moreover, in reality, it is not often logistically possible to implement a narrow‐angle course since the students are not a homogeneous group. The ongoing debate on common core versus specificity is an important one and will be taken up in the following discussion on the different pedagogic approaches to EAP, including a brief overview of their philosophical and theoretical orientations.

Approaches to EAP

Study Skills

As noted by Dudley‐Evans and St. John (1998, p. 24) the main principle underlying the teaching of study skills (e.g., taking notes in lectures, reading textbooks) is that knowing grammar and vocabulary are not sufficient conditions for developing the ability to function in an academic environment and that “there is a need to address the thought processes that underpin language use.” So, for example, a course focusing on academic reading skills would aim to target skills such as reading for relevant information and using contextual clues. Textbooks such as Jordan's (1990) Academic Writing Course are based on the functional‐notional approach to materials, with units built around rhetorical functions such as comparison/contrast, cause/effect, and so forth. Published study skills materials in the 1990s often made use of simplified or specially written texts by the writer, although nowadays it is generally agreed that authentic texts are the preferred option in EAP to reflect the target language derived from the needs analysis. MICASE (Michigan Corpus of Academic Spoken English) and its British counterpart BASE (British Academic Spoken English), consisting of authentic lectures and seminars, have been exploited for devising study skills materials which take a generic perspective on skills. Such an approach is seen by Swales and Feak (2000) as having certain advantages such that students have an opportunity to compare and share academic experiences.

While more narrow‐angle courses also have their respective advantages, a focus on disciplinary specificity may not be the only aspect to address in academic interactions. Ethnographic studies of various oral modes of academic skills have pinpointed sites of communication breakdown. For example, Flowerdew and Miller (1995), based on their analysis of lectures in a second language environment, put forward a four‐dimensional concept of culture to explain cross‐cultural breakdowns: ethnic, local, academic, and disciplinary. An approach which encompasses a socially situated understanding of the academic communicative setting can thus also help to inform the EAP teaching and learning situation. More recent studies on academic listening have investigated the multimodal nature (i.e., the accompanying visuals and gestures) of lectures and seminars (see Lynch, 2011).

Grammatical Structures and Vocabulary Items

Before the advent of the broad study skills approach in the 1980s, the field of ESP was first conceived in terms of a “register analysis” approach, specifically focused on EST (English for science and technology). The basic premise of this approach is that while scientific and technical writing use the same grammar as that of general English, certain grammatical structures and vocabulary items predominate. A seminal study by Barber (1988), based on “lexicostatistics,” showed that the predominant tense is the present simple and the passive voice is used more frequently in EST than in general English. In this approach, teaching units are built around grammatical structures such as the use of the passive for process descriptions.

Barber's research also highlighted the importance of subtechnical—that is, core—vocabulary (general vocabulary that has a higher frequency in a particular field), such as “consists of” and “contains” in EST. This kind of vocabulary has been usefully defined through corpus‐based analyses of particular EAP fields. Moreover, it is to be noted that vocabulary, rather than grammar, has been the focus of much recent EAP instruction for which corpus data have been exploited. For example, using a corpus of academic seminars on language and gender, international law, and entrepreneurship, Jones and Schmitt (2010) devised a set of vocabulary materials targeting technical (e.g., “regional body”), general (e.g., “at the outset”), and colloquial (e.g., “gut feeling”) discipline‐specific vocabulary and phrases in the seminars.

Discourse/Genre

Following the “register analysis” approach, the next major development in EAP, particularly in the field of EST, took a discourse‐based orientation, linking particular forms with particular rhetorical functions, such as defining, classifying, and so forth (Trimble, 1985), an approach underpinning much of the academic study skills materials described in the first section. However, the first discourse‐based study to truly examine “specificity” in EAP, in Hyland's sense, was Tarone, Dwyer, Gillette, and Icke's (1981) study with its focus on the rhetorical and communicative purposes of the passive in research articles from the field of astrophysics.

Table 1 A CARS model for article introductions (Swales, 1990, p. 141)

| Move 1: Establishing a territory |

| Step 1 claiming centrality (and/or) |

| Step 2 making topic generalization(s) (and/or) |

| Step 3 reviewing items of previous research |

| Move 2: Establishing a niche |

| Step 1A counter‐claiming (or) |

| Step 1B indicating a gap (or) |

| Step 1C question‐raising (or) |

| Step 1D continuing a tradition |

| Move 3: Occupying the niche |

| Step 1A outlining the purposes (or) |

| Step 1B announcing present research |

| Step 2 announcing principal findings |

| Step 3 indicating RA (research article) structure |

Tarone et al.'s study marked a watershed in the field of EAP and was followed by Swales's (1990) development of the concept of genre (a genre is conceived as a particular communicative event which has a specific communicative purpose recognizable by the users of the genre's discourse community). The Swalesian tradition of genre analysis has had a profound and lasting influence on EAP applied linguistics research and teaching, such as the CARS (create a research space) model for article introductions, as outlined in Table 1. Building on Swales's work on genre, Johns (1997) advocates a “socioliterate” approach to academic literacy in which students come to grips with academic genres through drawing on their own experiences with genres and discourse communities to aid them in interpreting, producing, and critiquing texts from various academic contexts.

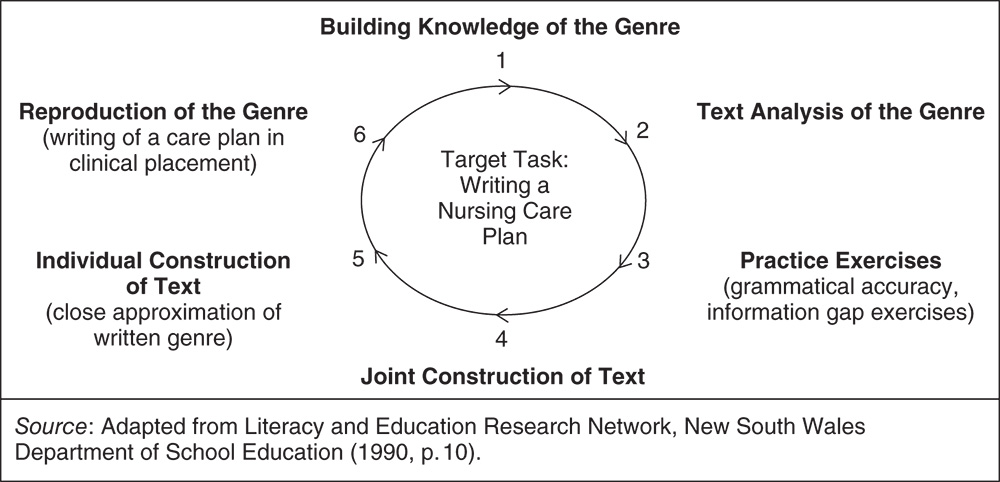

Another textual approach to genre is that of the “Sydney school” associated with Halliday's systemic‐functional lingustics (SFL), in which genres are defined as staged, goal‐oriented social processes. This approach is anchored in the need to teach socially valued genres, which are classified according to various rhetorical functions (e.g., explanation, description) based on linguistic criteria. An example of the SFL approach to pedagogy is Hussin's (2002, p. 30) task‐based instructional model for writing nursing care plans in the clinical part of trainee nursing programs in the academy (see Figure 2). In this teaching–learning cycle learners are offered support through “scaffolding” and repeated cycles (if necessary), thus increasing their knowledge of the content and context of the genre.

While the Swalesian and SFL approaches to genre accord importance to the textual aspect, the rhetorical genre studies approach tends to privilege the dynamic social and ideological context but at the same time does not neglect rhetorical and linguistic features. Bawarshi and Reiff (2010) lay out instructional guidelines for encouraging students to move repeatedly between analyzing the genre (i.e., identifying patterns in the genre's features) and the context (i.e., identifying the values and goals of the genre).

Figure 2 A genre approach to nursing care plans (Hussin, 2002, p. 30) Reprinted with permission from English for Specific Purposes, © 2002 by TESOL International Association. All rights reserved

Academic Literacies

Somewhat aligned with the rhetorical genre studies approach is the academic literacies approach whose practitioners emphasize the role that social context plays in EAP. In this approach practitioners use ethnographic methods to gather data about the social context, which is then used for developing EAP courses (see Wingate, 2015). In this era of the internationalization of universities, Wingate argues for an inclusive pedagogy whereby academic literacy instruction is fully integrated into the curriculum so as to cater for diverse student populations, for many of whom English is not their native language. The role of English as an academic lingua franca (see Mauranen, 2012) has also been supported by academic literacies practitioners. However, what distinguishes many adherents of the academic literacies approach is their critical perspective on EAP. For example, Lillis, Harrington, Lea, and Mitchell (2015) challenge the assumption that students should accept what they see as a rigid status quo, and unquestioning acceptance of conventionalized genres, arguing for transformative practices instead of normativity.

Critical EAP

The Swalesian tradition of genre implies a pragmatic orientation to EAP: that is, facilitating students to participate effectively in the academic community, although critical awareness is also encouraged. Proponents of a critical pedagogies approach take issue with this view of EAP for being too accommodationist toward power relations in the academy and failing to challenge the established status quo (Benesch, 2001; Chun, 2015). As a result, the content of EAP courses has been criticized for its imposition of Westernized values and ideologies and also the lack of value attached to the culture and rhetorical practices of the students' native language. However, Connor's (2011) model of intercultural rhetoric (tertium comparationis) addresses this cross‐cultural element with its focus on comparable analysis of the textual and linguistic data, also drawing on ethnographic methods. In a spirited defense, Hyland (2018) makes a case for the value of EAP in helping students unpack the textual norms and conventions of their disciplines, aided by evidence of language use from corpora (see Flowerdew, 2015; Nesi, 2016), arguing that EAP practices are also able to accommodate diversity.

Conclusion

The above overview of the five main approaches to EAP shows how much the field of EAP has evolved over the last 50 years. Issues regarding generic versus discipline‐specific pedagogy and more critical perspectives have also been raised. Three key developments which will no doubt have influence over the conceptualization and implementation of EAP in future years are the increasing interdisciplinarity of subjects: for example, physics in medicine, the role of English as an academic lingua franca, and the application of digital media (e.g., blogs and wikis) and corpus resources in the continually evolving and dynamic field of EAP.

SEE ALSO: Corpus Analysis of Business English; Corpus Analysis of Key Words; Genre and Discourse Analysis in Language for Specific Purposes; Needs Analysis and Syllabus Design for Language for Specific Purposes; Vocabulary and Language for Specific Purposes; Writing and Language for Specific Purposes

References

- Barber, C. L. (1988). Some measurable characteristics of modern scientific prose. In J. Swales (Ed.), Episodes in ESP (pp. 3–14). Oxford, England: Pergamon Press.

- Basturkmen, H. (2010). Developing courses in English for specific purposes. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bawarshi, A. S., & Reiff, M. J. (2010). Genre: An introduction to history, theory, research and pedagogy. West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press.

- Benesch, S. (2001). Critical English for academic purposes: Theory, politics and practice. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Chun, C. W. (2015). Power and meaning making in an EAP classroom: Engaging with the everyday. Bristol, England: Multilingual Matters.

- Connor, U. (2011). Intercultural rhetoric in the writing classroom. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Coxhead, A. (2000). A new academic wordlist. TESOL Quarterly, 34(2), 213–38.

- Dudley‐Evans, T., & St. John, M. (1998). Developments in English for specific purposes. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Flowerdew, L. (2015). Learner corpora and language for academic and specific purposes, In S. Granger, G. Gilquin, & F. Meunier (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of learner corpus research (pp. 465–84). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Flowerdew, J., & Miller, L. (1995). On the notion of culture in second language lectures. TESOL Quarterly, 29(2), 345–74.

- Flowerdew, J., & Peacock, M. (2001). Issues in EAP: A preliminary perspective. In J. Flowerdew & M. Peacock (Eds.), Research perspectives on English for academic purposes (pp. 8–24). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Hussin, V. (2002). An ESP program for students of nursing. In T. Orr (Ed.), English for specific purposes (pp. 25–39). Alexandria, VA: TESOL.

- Hyland, K. (2002). Specificity revisited: How far should we go? English for Specific Purposes, 21(4), 385–95.

- Hyland, K. (2006). English for academic purposes: An advanced resource book. London, England: Routledge.

- Hyland, K. (2009). Academic discourse. London, England: Continuum.

- Hyland, K. (2018). Sympathy for the devil? A defence of EAP. Language Teaching, 51(3), 383–99.

- Hyland, K., & Tse, P. (2007). Is there an “academic vocabulary”? TESOL Quarterly, 41(2), 235–53.

- Johns, A. M. (1997). Text, role, and context: Developing academic literacies. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Jones, M., & Schmitt, N. (2010). Developing materials for discipline‐specific vocabulary and phrases in academic seminars. In N. Harwood (Ed.), English language teaching materials: Theory and practice (pp. 225–48). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Jordan, R. R. (1990). Academic writing course. London, England: Longman.

- Lillis, T., Harrington, K., Lea, M., & Mitchell, S. (Eds.). (2015). Working with academic literacies: Case studies towards transformative practice. Fort Collins, CO: WAC Clearing House/Parlor Press.

- Lynch, T. (2011). Academic listening in the 21st century: Reviewing a decade of research. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 10(2), 79–88.

- Mauranen, A. (2012). Exploring ELF: Academic English shaped by non‐native speakers. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Nesi, H. (2016). Corpus studies in EAP. In K. Hyland & P. Shaw (Eds.). (2016). The Routledge handbook of English for academic purposes (pp. 206–17). London, England: Routledge.

- Paltridge, B., Starfield, S., & Tardy, C. (2016). Ethnographic perspectives on academic writing. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Swales, J. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Swales, J., & Feak, C. (2000). English in today's research world: A writing guide. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Tarone, E., Dwyer, S., Gillette, S., & Icke, V. (1981). On the use of the passive in two astrophysics journal papers. The ESP Journal, 1(2), 123–40.

- Trimble, L. (1985). EST: A discourse approach. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Wingate, U. (2015). Academic literacy and student diversity: The case for inclusive practice. Bristol, England: Multilingual Matters.

Suggested Readings

- Charles, M., & Pecorari, D. (2016). Introducing English for academic purposes. London, England: Routledge.

- Ding, A., & Bruce, I. (2017). The English for academic purposes practitioner: Operating on the edge of academia. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave.

- Hyland, K., & Shaw, P. (Eds.). (2016). The Routledge handbook of English for academic purposes. London, England: Routledge.

- Hyon, S. (2018). Introducing genre and English for specific purposes. London, England: Routledge.

- Paltridge, B., & Starfield, S. (Eds.). (2013). The handbook of English for specific purposes. Oxford, England: Wiley‐Blackwell.

- Swales, J. (2004). Research genres. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

English in Asian and European Higher Education

ANDY KIRKPATRICK AND SARAN KAUR GILL

The internationalization of higher education (HE) has led to a noticeable increase in the number of courses and degrees taught through the medium of English. One of the main reasons is the fact that HE is a lucrative industry. As a result, there is a need to internationalize curricula as part of the strategy to attract students from different parts of the world to universities in varying locations of the globe. Another reason is that nations want to be active players in the knowledge economy and thus there is the need to be able to access and contribute to the latest advances in the field of science and technology. All of these align with the need to attract international students and staff and to publish and be cited internationally, both important criteria of the Shanghai Jiaotong and the Times Higher ranking schemes for universities.

The increase in the number of programs taught in English in continental Europe has been documented in a series of studies conducted by Wachter and Maiworm (2008, 2014) which show a rise in English‐taught programs from 725 in 2001 to 8,089 in 2014. The authors stress, however, a number of points: first, despite this dramatic increase in English‐taught programs, only a small proportion of students (1.3%, representing 290,000 students) are actually enrolled in these programs; second, some 80% of these programs are at master's level; and, third, that the countries of northern Europe provide the most programs and southern Europe the least. Nevertheless, this rapid increase of English in HE in Europe and, as will be shown below, Asia, would appear to confirm Coleman's prediction that “it seems inevitable that English, in some form, will definitely become the language of higher education” (Coleman, 2006, p. 11).

In the European context, this relatively sudden and rapid shift to English‐medium programs is one consequence of the Bologna Process, named after the Bologna Declaration signed on June 19, 1999 in Bologna. The main aim of the Bologna Process is to create a European higher education area (EHEA) which will facilitate academic cooperation and staff and student exchange within Europe. The adoption of English as the common language to facilitate academic cooperation and exchange has led to the argument that “what emerges unambiguously is that in the Bologna Process, internationalization means English‐medium higher education” (Phillipson, 2009, p. 37).

In order to attract international students, many countries in Asia have also opened their doors to a model of transnational education with collaborative links with foreign institutions of higher learning, a move that itself necessitates a change in language policy from national languages to English.

Two recent developments are encouraging a Bologna‐like move to ensure degree programs converge. The first is the agreement reached in 2012 at the Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit to seek ways in which to facilitate staff and student mobility across the universities of the region. The second is that the Association of Southeast Asian (ASEAN) Universities Network, which comprises some thirty universities in the countries of ASEAN, is also seeking to encourage staff and student mobility across the universities of the network.

Malaysia was one the earliest Asian countries to encourage transnational private HE opportunities for its citizens and to develop the nation as a regional hub of education (Gill, 2004, p. 140). Malaysia provided HE opportunities in English as far back as the 1980s, when Malaysian educational entrepreneurs responded to a local need for cheaper international degrees by creating a system whereby students did two years at a Malaysian private college and then, through credit transfer, could enter the third year of US universities. Based on this model, they then went on to initiate “twinning programs” (“1 + 2” and “2 + 1”) with British and Australian universities in the late 1980s. As a consequence, Malaysia has come to have some hundred private colleges and private university colleges, which have partnership programs with universities in Australia, the UK, the USA, and other English‐speaking countries.

In addition, there are now a total of more than a dozen private universities established after 1997–8 when the economic crisis set in. These include engineering universities set up by the three public utility corporations in Malaysia, Telekom (the national telecommunications company), Tenaga Nasional (the national electricity board), and Petronas (the national petroleum company) to branch campuses of foreign universities, as mentioned below (Gill, 2004, p. 141). More recently, several UK universities have established campuses in Malaysia. EduCity, a development just outside the city of Johore Bahru, is home to three UK universities, namely Newcastle, Reading, and Southampton. Indeed, UK universities now have 39 campuses outside Britain, and many more have some form of twinning arrangement with local universities. Malaysia's role is particularly significant. As the Economist notes, “Malaysia now has more students studying for the British qualification than any country bar Britain itself” (Economist, 2018).

Many Asian countries and universities are now trying to establish themselves as education hubs and attract international students from the region. Not only does this bring the university income and prestige, it can also be attractive to regional students, as fees and living expenses are appreciably lower than those in countries such as the UK, the USA, and Australia, where many international students currently study.

China's University and College Admission Systems (CUCAS; www.cucas.edu.cn) lists English medium instruction (EMI) courses offered by Chinese universities and it is clear that Chinese universities are increasing the number of EMI courses which they offer. As long ago as 2001, the then premier, Zhu Rongji, said that he hoped all classes at his alma mater, Tsinghua University's School of Economics and Management, would be taught in English, as China needed to be able to exchange ideas with the rest of the world (South China Morning Post, 2001).

Even Indonesia, the country that was a role model for Malaysia in its own language planning stages, is pragmatically relaxing its control over mother‐tongue medium of instruction in favor of English, in order to attract international students. This is reflected by an advertisement for a medical degree from Padjadjaran University as a program that is conducted fully in the English language.

Japan is also embracing international education and introduced the Global 30 Project, which was designed to attract international students to Japan to study in one of 30 universities. The results have been disappointing, with fewer than 22,000 international students enrolled in 2011. Indeed the low numbers of international students has led to the recent abandoning of the Global 30 Project, which also drew criticism as many of the EMI programs were exclusively for international students and excluded local Japanese students. (McKinley, 2015). This has now been replaced by the Super Global Universities Project, under which 13 of Japan's top universities have been given extra funding to help them compete internationally and a further 24 universities have been identified whose role is to show Japan in a more global light (Kirkpatrick, 2017)

Despite the increase in English‐medium programs, the national languages in respective Asian and European countries are not forgotten (although other languages often are). Apart from Singapore, which made the decision to use English as the main medium of instruction in the entire educational system, including universities, many other nations in Asia have adopted a bilingual system of education. Yet how precisely to introduce this limited notion of bilingual education (the national language + English) remains the subject of controversy and experimentation. One principle being tried is that of “parallel languages” (Preisler, 2009), but this has yet to be defined. At one extreme it means that all subjects should be taught in the national language and English. At the other, universities may simply offer courses in English as they so wish. Preisler suggests, however, that the notion of “complementary” languages needs to be introduced where “the two languages will be functionally distributed within the individual programme according to the nature of its components, that is, the national or international scope of their academic content and orientation of their students” (2009, p. 26).

At the Hong Kong University of Education students take degrees in Cantonese, Putonghua, or English, and many degrees have some modules taught in Cantonese and others in English. However, the situation at the other seven government universities in Hong Kong demonstrates how slow institutions have been to embrace the notion of complementarity, as all, with the exception of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, are English‐medium only universities. This is despite the government's policy of creating a citizenry that is trilingual in Cantonese, Putonghua, and English and biliterate in Chinese and English. Thus the overwhelming majority of HE degrees and programs in a Chinese city with a population of more than 7 million are taught (officially, in any event) only through English. In other words, complementarity is not the norm for HE in Hong Kong—English‐medium only is.

This rapid growth in English medium education has often been implemented, especially in universities in Asia, without adequate planning and preparation. In a worldwide study mapping the growth of EMI, which encompassed 54 countries (Dearden, 2015), key findings were:

- Apart from a few local exceptions, EMI is expanding rapidly, especially in the HE sector, as a result of a perceived need to internationalize institutions.

- The private HE sector is putting pressure on the state HE sector to convert their programs to EMI as the latter need to compete for students; in turn, the tertiary sector is putting pressure on the secondary sector to also teach subjects through the medium of English.

- In many countries the introduction of EMI is not supported by preservice teacher training or teacher professional development.

- Not all teachers are equipped linguistically to be able to effectively deliver subject content to students.

- Where there are concerns about the introduction of EMI, these are to do with its potentially divisive nature: the likelihood that it will either create social elites based on English‐language proficiency or contribute to already existing social inequalities. Other concerns relate to the deleterious impact that EMI may have on the home language (Macaro, Hultgren, Kirkpatrick, & Lasagabaster, 2019).

In conclusion, there is a definite and continuing trend within both Europe and Asia to move toward English medium education in higher education. At the same time, there are concerns that, in many places, this is being introduced without adequate planning and preparation, and without adequate thought about the future role of other languages as languages of education.

SEE ALSO: Varieties of English in Asia; World Englishes and Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages

References

- Coleman, J. A. (2006). English medium teaching in European higher education. Language Teaching, 39, 1–14.

- Dearden, J. (2015). English as a medium of instruction: A growing global phenomenon. Oxford, England: British Council.

- Economist. (2018, August 25). Dreaming of new spires. The Economist.

- Gill, S. K. (2004). Medium‐of‐instruction policy in higher education in Malaysia: Nationalism versus internationalization. In J. W. Tollefson & A. B. M. Tsui (Eds.), Medium of instruction policies: Which agenda? Whose agenda? (pp. 135–52). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Kirkpatrick, A. (2017). The languages of higher education in East and Southeast Asia: Will internationalisation lead to Englishisation? In B. Fenton‐Smith, P. Humphreys, & I. Walkinshaw (Eds.), English medium instruction in higher education in Asia‐Pacific: From policy to pedagogy (pp. 21–36). Dordrecht, Germany: Springer.

- Macaro, E., Hultgren, K., Kirkpatrick, A., & Lasagabaster, D. (2019). English medium instruction: Global views and countries in focus. Language Teaching, 52(2), 231–48. doi: 10.1017/S0261444816000380

- McKinley, J. (2015, November 23–26). EMI in a Japanese Global 30 university. Presentation at the Language Education and Diversity Conference, Auckland.

- Phillipson, R. (2009). English in higher education: Panacea or pandemic? Angles on the English‐Speaking World, 9, 29–57.

- Preisler, B. (2009). Complementary languages: The national language and English as working languages in European universities. Angles on the English‐Speaking World, 9, 10–28.

- South China Morning Post. (2001, September 20). China varsities to teach in English. South China Morning Post.

- Wachter, B., & Maiworm, F. (2008). English‐taught programmes in European higher education. Bonn, Germany: Lemmens.

- Wachter, B., & Maiworm, F. (2014). English‐taught programmes in European higher education: The state of play. Bonn, Germany: Lemmens.

Suggested Readings

- Doiz, A., Lasagabaster, D., & Sierra, J. M. (Eds.). (2013). English‐medium instruction at universities: Global challenges. Bristol, England: Multilingual Matters.

- Fenton‐Smith, B., Humphreys, P., & Walkinshaw, I. (Eds.). (2017). English medium instruction in higher education in Asia‐Pacific: From policy to pedagogy. Dordrecht, Germany: Springer.

- Haberland, H., Lonsmann, D., & Preisler, B. (Eds.). (2013). Language, alternation, language choice and language encounter in higher education. Dordrecht, Germany: Springer.

- Macaro, E., Curle, S., & Pun, J. (2018). A systematic review of English medium of instruction in higher education. Language Teaching, 51(1), 36–76.

- Rassool, N., & Mansoor, S. (2007). Global issues in language education and development. In N. Rassool (Ed.), Global issues in language, education and development (pp. 218–41). Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

- Tan, A. M. (2002). Malaysian private higher education: Globalisation, privatization, transformation and marketplaces. London, England: ASEAN.

Note

- Based in part on S. K. Gill and A. Kirkpatrick (2012). English in Asian and European higher education. In C. A. Chapelle (Ed.), The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics, John Wiley & Sons Inc., with permission.

English for Business

CATHERINE NICKERSON

Introduction

English for business is referred to in the academic literature in a number of different ways, including English for business, business English (BE), English for specific business purposes (ESBP), international business English (IBE), and business English as a lingua franca (BELF). When English for business is taught in professional business settings, it overlaps with English for occupational purposes (EOP). When it is taught as part of a tertiary course, it also overlaps with English for academic purposes (EAP). One of the hallmarks of research into English for business is the fact that it has largely been data driven. As a result, it has been characterized by reference to a variety of different research approaches, including sociolinguistics, intercultural communication, discourse analysis, business communication, management studies, English as a lingua franca, and English for specific purposes.

English is used routinely for commerce and industry across national borders in all parts of the globe (e.g., Rogerson‐Revell, 2007, discusses multicultural meetings in the European context; Evans, 2013, focuses on Hong Kong; Lockwood and Forey, 2012, report on the call center industry worldwide, etc.). It is almost always chosen as at least one of the official corporate languages used within a multinational corporation, even if both the corporation and its head office are located in a non‐English‐speaking country. Such corporate language policies have had varying degrees of success. For example, Louhiala‐Salminen, Charles, and Kankaanranta (2005) look at the challenges posed by a Scandinavian corporate merger in their seminal study of English as a business lingua franca; Du‐Babcock and Tanaka (2017) investigate leadership construction and decision making in intra‐Asian English; Gimenez (2002) reports on the impact of using English within the Argentinian subsidiary of a European multinational. In addition, English is often used in business transactions within national borders in countries where it is one of the language choices available as a result of that country's colonial past, (e.g., in India, the Philippines, and Singapore), and it may also be chosen for pragmatic reasons because there is an extensive expatriate business community who are unfamiliar with the local language, (e.g., in the Gulf Region). Finally, large parts of the world, (e.g., the United States, Australia, Anglophone Canada, the United Kingdom etc.), do business primarily in English, as it is the first language of most of the population.

There are many millions of business people across the globe who speak or write English on a daily basis, and hundreds and thousands of business transactions are initiated, negotiated, and completed using English either on its own or in combination with one or more other languages. Exactly how many people are involved is difficult to establish because of the wide range of different methodologies that have been used to measure this. In terms of economic value, however, first language interactions alone could account for as much as 30% of the world's gross domestic product (Graddol, 2006). The real value is clearly much larger if second and foreign‐language users of English are also taken into account. Although there are some indications that the use of other languages, such as Chinese, Hindi, and Arabic, will increase in business contexts, most scholars agree that English will continue to dominate for at least the next 50 years.

Because of its dominance, English has been analyzed more than any other business language. In the past three decades, researchers interested in English for business have looked at a variety of different forms of workplace communication, including business meetings, negotiations, presentations, sales letters, application letters, e‐mail, annual reports, audit reports, advertising texts, various forms of computer‐mediated communication, and corporate home pages. They have also studied the consequences of using business English across the globe, particularly for those people who do not speak it as a first language. Some researchers have focused primarily on the forms of communication that are used in business (e.g., Handford, 2010, looks at business meetings; Gimenez, 2014, looks at computer‐mediated communication in the workplace; de Groot, Nickerson, Korzilius, & Gerritsen, 2015, look at annual general reports, etc.), while others have looked specifically at the challenges faced by speakers of other languages in business English encounters and the ways in which they, and others, deal with them (e.g., Rogerson‐Revell, 2010, identifies the accommodation strategies used in international business meetings in English; Kankaanranta & Louhiala‐Salminen, 2010, elaborate on the perceived neutrality of English for Finnish business people, etc.). A third group of researchers have investigated how English is used to facilitate a specific type of business activity, and also how it interfaces with the other languages in use within the same context (e.g., Hornikx, van Meurs, & de Boer, 2010, investigate the effectiveness of using English slogans in advertising in the Netherlands; Flowerdew & Wan, 2010, consider the combination of speaking tasks in Cantonese or Mandarin as well as writing tasks in English that auditors in Hong Kong need to complete in parallel to successfully carry out an audit, etc.). The findings of these different types of studies have all contributed to our understanding of business English used as discourse—that is, “how people communicate using talk or writing in commercial organizations in order to get their work done” (Bargiela‐Chiappini, Nickerson, & Planken, 2013, p. 3).

English for business is a multibillion dollar industry, and British and American varieties of English still tend to dominate in textbooks and commercially produced training materials, despite the fact that many business people will use English primarily in their own region and will never interact regularly with their counterparts from the United Kingdom or the United States. In addition, as several researchers have shown, there is a very large gap between what real business people say or write and the models of language use that most textbooks include (Chan, 2009; Evans, 2012; but see Handford, Lisboa, Koester, & Pitt, 2011, for a research‐based textbook).

Researching Written and Spoken Business English

For written business English, the type of analysis generally referred to as “genre analysis” has been extremely influential. Vijay Bhatia's 1993 publication Analysing Genre: Language Use in Professional Settings extended an existing English for specific purposes (ESP) approach that had been pioneered by John Swales for academic writing, and reapplied it to some of the most important forms of written business communication that were in use at the time, such as application letters and sales letters. Genre analysis focuses on the communicative purpose of a text as a whole and attempts to explain how the content and form of the text contribute to this purpose; in doing so, it identifies a set of moves that people include in a text in which content and form are combined in a specific way. In his later publications, Bhatia has continued to develop this work with particular reference to strategic language use on the part of individual genre users, and he has explored the complex relationship between a text and the surrounding context (Bhatia, 2008, 2010). Many applied linguists interested in the written forms of English for business have been influenced by Bhatia's ideas, and, more recently, several of them have also extended his approach to the spoken forms of English for business. They include Stephen Evans (business presentations and e‐mail correspondence), Almut Koester (sales letters and negotiations), Anne Kankaanranta (e‐mail correspondence), and Michael Handford (business meetings). All of these scholars are active as teaching practitioners, so their research work has also influenced the ways in which business English is taught. Within the broader field of LSP (language for specific purposes), Johns's study of cohesion in different types of discourse is historically important as one of the first published studies on English for business (Johns, 1980), and the contrastive studies of business correspondence by Jenkins and Hinds (1987) and by Yli‐Jokipii (1994) are landmark studies for the 1980s and 1990s, respectively.

For spoken forms of communication, conversational analysis (CA) and discourse analysis (DA) (especially the approach pioneered by John Sinclair and Malcolm Coulthard at Birmingham University in the United Kingdom from the late 1970s onward) have been influential on our understanding of the ways in which English is used for business purposes. An important study of spoken business English that uses a CA approach is Boden's account of meetings in the United States in three different sectors: health, academia, and business (Boden, 1994). CA allows Boden to deconstruct the interactions that take place within the meetings and to show the contrast between the three sectors. She also looks at the way in which the organizations involved are shaped by the language they use. Mirjaliisa Charles's work on British business negotiations using discourse analysis (e.g., Charles, 1996) has remained influential, as has the work by Bargiela‐Chiappini and Harris on meetings and other forms of spoken business communication, both in English and in other languages (e.g., Bargiela‐Chiappini & Harris, 1997).

For the last two decades, many researchers looking at spoken business English have taken a discourse approach, in which their focus has been on the specific types of strategies that people use in business transactions. The 2005 study of English as a business lingua franca in Finnish and Swedish corporate mergers by Louhiala‐Salminen et al. (2005), for instance, shows that different national cultures use different strategies, which may then be interpreted by the participants in a meeting in both positive and negative ways. Likewise, the series of studies by Rogerson‐Revell on multicultural meetings in Europe shows how speakers with different proficiency levels in English cooperate with each other to co‐construct shared meanings (Rogerson‐Revell, 2007, 2008, 2010). Finally, the Language in the Workplace Project (LWP), directed by Meredith Marra at Victoria University Wellington in New Zealand, uses a number of different methodological approaches in the study of communication in the workplace, with an emphasis on spoken interactions. The methodologies used, together with the project's findings, are accessible via the project Web site, alongside a set of publications and pedagogical materials (www.victoria.ac.nz/lals/lwp/).

The Effects of Using English for Business