Q

Qualitative Corpus Analysis

VICTORIA HASKO

Definition and Philosophy

Qualitative corpus analysis is a methodology for pursuing in‐depth investigations of authentic language use representative of purposefully selected communicative situations. The language samples are digitally captured, documented as to their origins and ecology, stored as electronic language corpora, annotated as needed, and made available for digital access, retrieval, and analysis via a computer. Researchers using qualitative corpus analysis as the methodological basis for their investigations adopt an exploratory, inductive approach to the empirically based study of how the meanings and functions of linguistic forms found in a specific corpus interact with diverse ecological characteristics of language used for communication (speaker age, gender, level of education, and socioeconomic background; place and time of a communicative event; relationship between interlocutors; speech modality; etc.). A common belief shared by all corpus linguists is that it is important to base linguistic investigations on “real data,” that is, actual instances of oral or written communication as opposed to contrived or “made‐up” texts. Unique goals of qualitative corpus analysis may include careful documentation of numerous contextual factors that capture the people and the setting in which the language was produced in depth; rich annotation schemes that may involve manual markup; as well as interpretation of the retrieved corpus query outputs in the intellectual traditions from an appropriate subfield of language studies and with consideration of the accompanying contextual data. This entry summarizes the evolution of the field, outlines the methodological foundations and principles of qualitative corpus analysis, and enumerates major areas of application of the methodology.

Evolution of Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches to Corpus Analysis

Although today we tend to associate all branches of corpus linguistics with a machine‐ readable format, language corpora were assembled and analyzed before computers by numerous language luminaries, such as Samuel Johnson, Alexander J. Ellis, Joseph Wright, James Murray, Harold Orton, and Sir Randolph Quirk, with application to grammatical, lexicographical, and dialectological endeavors (see Francis, 1992, for details). Later, field and structural linguists, such as Franz Boas, Edward Sapir, Leonard Bloomfield, and Kenneth Lee Pike, adhered to the principle of basing studies on samples of attested observable data (McEnery, Xiao, & Tono, 2006). Although early “corpora” consisted of handwritten notes, the scrupulous fieldwork of the scholars documenting authentic language use “in situ” was conducted in what we can identify today as the spirit of qualitative corpus analysis.

The emergence and firm establishment of corpus linguistics as a methodology, in its modern, computer‐based form, are associated with the groundbreaking efforts of W. Nelson Francis and Henry Kučera in developing the Brown Corpus of English in the 1960s. Their compilation of a 1‐million‐word corpus (an impressive size at the time of its first release in 1964) paved the way for quantitative corpus research but also undeniably created the foundation for supporting qualitative corpus‐based inquiry. Thus, the Brown Corpus was not compiled as a bank of unconnected sentences but rather was designed to include 2000‐word samples of meaningful, cohesive discourse, which were chosen on the basis of their representation of a wide range of diverse styles and varieties of prose. In addition, the tagging system taxonomy applied to the corpus was a step forward from raw corpora, illustrating the possibilities of carrying out more refined linguistic and metalinguistic analyses through corpus encoding. In terms of corpus retrieval options, the Brown Corpus allowed researchers to use word + context as criteria to retrieve not only isolated word forms but also full‐sentence citations. These characteristics reflect the most basic utility requirements for a properly compiled corpus suitable for qualitative analysis.

Since the 1980s, the field of corpus linguistics has been dominated by quantitative approaches fueled by the development and propagation of super‐corpora and data sets, such as the British National Corpus (BNC; 100 million words), the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA; 450 million words), Google Books (200 billion words), and so forth. Qualitative corpus linguists, while utilizing these general corpora, tend to believe that small, intimately examined and documented corpora are also needed for fruitful micro‐corpus, higher‐level analyses of language use (Costa, Reis, de Souza, & Moreira, 2017). In the field of learner corpus analysis in particular, genre‐specific, learner‐centered, context‐dependent, and culture‐bound learner corpora compiled by second language acquisition researchers are seen as a more ecologically valid source of data about the dynamics of interlanguage development of a specific learner population than larger generic corpora (e.g., see Hasko, 2013). Accordingly, smaller corpora have been springing up alongside the super‐corpora in the form of specialized, annotated databases designed by corpus linguists for meticulous, in‐depth qualitative exploration of select linguistic phenomena or language varieties. These customized corpora allow qualitative corpus analysis researchers to concentrate on the fine details of linguistic interactions and to relate these details to the specifics (and sometimes the chronology) of the captured speech events as well as the larger social communities or ideologies that they are a part of.

Most recently, the advances in digital technologies, availability of inexpensive or free corpus tools, as well as the exponentially growing online data sets resulting from the increasing global participation in social media have created additional powerful affordances for fueling individual researchers' efforts to compile specialized DIY (do‐it‐yourself) corpora. Such corpora range from published collections of 1–2 million words to much smaller and highly specialized data sets that are publically available (see the LINGUIST List's corpus bank, 2018) or privately utilized corpora described in academic publications. The prospects for conducting thorough and multifaceted qualitative corpus investigations are even brighter with the emergence of multimodal corpora that allow for automatic markup of not only speech but also such communication modalities as hand gestures, facial expressions, body posture, and acoustics (e.g., Cafaro et al., 2017), alongside artificial intelligence tools.

Methodological Foundations

Qualitative corpus analysis is dually informed by the traditions of qualitative linguistic research as well as by research methods specific to corpus linguistics. The methods and principles for conducting qualitative corpus analysis are summarized below.

Corpus Design

A corpus suitable for fine‐grained linguistic analysis should consist of complete, naturally occurring texts (oral or written) whose origins and provenance are well documented (see Sinclair, 1996). The requirement for naturally occurring speech acknowledges the importance of analyzing authentic and attested data, as opposed to invented examples. The focus on complete texts and the importance of the social and communicative context in analyzing language is central to qualitative corpus analysis and the qualitative research paradigm in general, as “the context plays a part in determining what we say; and what we say plays a part in determining the context” (Halliday, 1978, p. 3). Therefore, it is expected that texts are carefully selected to offer a satisfactory representation of modalities, genres, discourse communities, settings, and so on, that the corpus is designed to reflect, with such texts varying from full book length to 140‐character tweets or even shorter text messages or transcripts of voice chats, per research goals.

Corpus Markup and Annotation

Corpus markup represents an important method of documenting the aforementioned descriptive “metadata” pertaining to the collected linguistic samples. Corpus markup is carried out by inserting standardized codes or tags in each of the documents of a raw corpus, with the codes kept separate from the corpus data per se. A number of markup schemes have been developed for encoding such specifications as document‐wide information (document length, distributor, date, etc.), structural elements (e.g., chapter, titles, headings), and subparagraph structure (e.g., quotations, abbreviations, terms).

Annotation is a corpus‐encoding method similar to markup, except that the former involves the encoding of linguistic information (for in‐depth discussion of linguistic annotation design, creation, tools, evaluation, etc., see Garside, Leech, & McEnery, 1997; Ide & Pustejovsky, 2017). Corpus annotation can be characterized by varying degrees of specificity and may address different areas of linguistic analysis, such as part‐of‐speech tagging (the most common type); lemmatization; parsing; morphological, phonetic, prosodic, pragmatic, semantic, discourse, metaphorical annotation; and error tagging. The last types of annotation and error tagging are more commonly associated with qualitative corpus analysis research because of the complex manifestations of the linguistic phenomena they cover. For example, specific types of harassment in offensive social media posts (Rezvan et al., 2018) or symptoms of trauma in suicide notes (Galasiński, 2017) are not immediately identifiable on the surface or available for automatic retrieval from raw texts, because their linguistic instantiations are realized across morphemes or even hundreds of words of running text and may require human interpretation. Various taggers and text‐mining tools are available for automatic annotation of large quantities of data, and artificial intelligence tools and natural language processing (NLP) tools are growing increasingly sophisticated in their capabilities and accessibility both in terms of price and ease of use (e.g., Niekler, Wiedemann, & Heyer, 2017). However, when the encoding of finer linguistic or discipline‐specific categories or phenomena requires a greater capacity for subtle judgment and the drawing of inferences – which are often cornerstones of rich and thorough qualitative investigations – manual or semi‐manual annotation may still need to be implemented by human coders.

Accuracy and consistency are crucial factors for ensuring the reliability of the largely interpretive process of corpus annotation. Such solutions as developing a coding manual as a reference for other researchers, thorough descriptions of the codes, instructions for applying these codes, flowchart‐style decision algorithm trees to assist coders, adherence to and continuous negotiation of the international community standards, and so forth, are being utilized to minimize any arbitrary and individual variation in the manual annotation of complex linguistic phenomena.

Data Retrieval

The drudgery of painstaking corpus markup and annotation during qualitative corpus analysis starts paying off at the stage of data retrieval. The more complex the nature of the analyzed phenomena, the more corpus utility depends on the proper compilation and annotation of the corpus prior to carrying out the query; for this reason, corpora compiled for qualitative corpus analysis are typically conceptualized and designed with fairly specific research goals in mind. Various software applications are available for processing corpora, that is, for searching through it for particular words or surface structure, for displaying parts of it, or for analyzing specific linguistic features (see corpus-analysis.com for a list of select tools). While such programs can operate on plain text files, they take full advantage of annotated corpora, allowing for retrieval of all instances of surface structures containing the target tag(s) in the sampled corpus within a few seconds. Data searches can be as sophisticated as the annotation scheme applied to the corpus data. Qualitative corpus research can also start out from purely quantitative data such as keyword or collocate frequencies, which can be further used by qualitative researchers as the basis for surveying possible patterns; the initial corpus outputs can then be further refined by the researchers based on carefully selected variables and supplemented with non‐corpus‐based data relevant to the project at hand.

The capabilities for automatic or semi‐automatic data retrieval during qualitative corpus analysis enable the scholarly community to replicate searches, with the purpose of reproducing and verifying outcomes of linguistic investigations, especially when corpora are publicly available and corpus markup, annotation, and problem‐oriented tagging schemes are made available along with the published corpus. This is a significant benefit for qualitative studies, which are often criticized for the difficulty of scientific reproduction and verification of their analyses.

Data Interpretation

Qualitative corpus analysis is a unique research enterprise, yet, at the same time, it draws on a variety of previously established methods of linguistic inquiry for the purpose of data interpretation. Thus, text selection, corpus size, markup, and annotation schemes are typically predetermined in qualitative corpus analysis before corpus compilation, and are informed by such qualitative methodologies as narrative inquiry, genre studies, (critical) discourse and conversation analysis, ethnography of communication, contrastive analysis, and semantic and pragmatic analysis.

The methodological merger between qualitative corpus analysis and “traditional” qualitatively oriented approaches is organic, in that they are oriented toward “telling the story” by accounting for the richness of the contextual factors that situate quantitative findings in the ecology of human communication. The merger is also mutually beneficial. On the one hand, without the insights accumulated by qualitative linguistic methodologies from various interdisciplinary areas over the last century, corpus methodology alone would lack the sophistication of the methodological apparatus, as well as the subject matter foundation for describing and interpreting the complex nature of human communication. For these reasons, in qualitative corpus research, corpus evidence is often supplemented with further experimental data (interviews, self‐reports, elicitation, etc.), introspection, and inventions (see Chafe's principles, 1992). On the other hand, non‐corpus‐based qualitative approaches are typically constrained by a rather limited size of text and a painstaking approach of accounting for each individual example of analyzed phenomena every time data analysis is conducted, whereas qualitative corpus analysis methodology creates affordances for (collaborative) compilation of larger data sets; computer‐aided storage, annotation, and automatic retrieval; and replication and sharing of empirical evidence.

Although qualitative corpus analysis is often construed as not being concerned with frequencies and statistical classification of linguistic features identified in the data, the value of mixing qualitative and quantitative approaches to corpus research is uncontestable. Rich insights that stem from qualitative corpus analysis can serve as a precursor for quantitative approaches, allowing for quantification and classification of the linguistic forms, that is, for generalizing the findings of the qualitative analysis of a sample corpus to a larger population (Schmied, 1993). In practice, qualitative corpus analysis is almost invariably used alongside quantitative approaches. By contrast, the results of quantitative corpus analysis can be explicated and illustrated through the interpretive power of qualitative methodology beyond the bare statistics of occurrence. The most interesting and nuanced research questions are typically not amenable to purely quantitative corpus output (Timmis, 2015).

Practical Applications

A number of subfields of linguistics have benefited significantly from the application of insights and findings that stemmed from qualitative corpus analysis investigations. Corpora designed and executed in accordance with the aforementioned principles of qualitative corpus analysis methodology have had a major impact in the areas of sociolinguistics, discourse analysis, pragmatics, semantics, and forensic linguistics. The field of lexical studies is a particularly robust example: Modern dictionaries are able to offer significantly more precise, comprehensive, and up‐to‐date lexical entries because lexicographers have gained access to vast yet methodically annotated corpora, which enables them to tease apart and illustrate usage differences attributed to the wealth of contextual and interpersonal variables. Similarly, grammarians routinely rely on corpora both to verify probabilities of occurrence of grammatical elements in quantitative terms and to qualitatively hone, illustrate, and fine‐tune grammarians' claims. Today, major publishing houses support corpus development and the publication of corpus‐based dictionaries, grammars, and reference books (e.g., see COBUILD's extensive catalog of text‐based and electronic dictionaries and reference materials).

Qualitative corpus analysis has revolutionized the field of language education by providing an empirical basis for intuitions about what authentic interactions look like and which language structures, strategies, and patterns should be highlighted in language courses and analyzed for effective pedagogical treatment (Granger, 2002 and onward). Corpora comprised of cross‐sectional and longitudinal samples of learner speech have allowed second language (L2) researchers to investigate the dynamics of L2 development at different proficiency levels and with regard to such variables as distance and transfer effects between first language (L1) and L2, instructional context, and age of acquisition.

Conclusions

Qualitative corpus analysis is a methodology that has made a significant contribution to language studies by enabling researchers to access, highlight, and methodically explore attested linguistic phenomena that range from frequent to rare, simple to complex, and easily discernible to stretched over thousands of words. Fueled by technological innovation, informed by the breadth of multimethod approaches, and built upon the successes of various subfields of linguistic research, qualitative corpus analysis offers a unique and promising path to the continued discovery of the complexities of human communication, with richness, precision, and appreciation for its multifaceted ecology. In the future, the influence and growth of qualitative corpus analysis are likely to be spurred by both the “social turn” in many subfields of linguistics, favoring in‐depth, contextually grounded methodological approaches to data analysis, and additional breakthroughs in artificial intelligence and NLP tools, optimizing and refining automatic corpus annotation and mining and alleviating the laboriousness of the processes of manual corpus compilation and analysis.

SEE ALSO: Corpus Linguistics: Quantitative Methods; Computer‐Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS); Interlanguage; Multimodal Discourse Analysis

References

- Cafaro, A., Wagner, J., Baur, T., Dermouche, S., Torres Torres, M., Pelachaud, C., . . . & Valstar, M. (2017, November). The NoXi database: Multimodal recordings of mediated novice‐expert interactions. Proceedings of the 19th ACM International Conference on Multimodal Interaction (pp. 350–9). New York, NY: ACM.

- Chafe, W. (1992). The importance of corpus linguistics to understanding the nature of language. In J. Svartvik (Ed.), Directions to corpus linguistics: Proceedings of the Nobel Symposium 82, Stockholm (pp. 79–97). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter.

- Costa, A. P., Reis, L. P., de Souza, F. N., & Moreira, A. (Eds.). (2017). Computer supported qualitative research: Second international symposium on qualitative research (ISQR 2017) (Vol. 621). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Francis, W. N. (1992). Language corpora B.C. In J. Svartvik (Ed.), Directions in Corpus Linguistics: Proceedings of the Nobel Symposium 82, Stockholm, 4–8 August 1991 (pp. 17–34). Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter.

- Galasiński, D. (2017). Discourses of men's suicide notes: A qualitative analysis. London, England: Bloomsbury.

- Garside, R., Leech, G. N., & McEnery, T. (1997). Corpus annotation: Linguistic information from computer text corpora. New York, NY: Longman.

- Granger, S. (2002). A bird's‐eye view of computer learner corpus research. In S. Granger, J. Hung, & S. Petch‐Tyson (Eds.), Computer learner corpora, second language acquisition and foreign language teaching (pp. 3–33). Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins.

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. Baltimore, MD: University Park Press.

- Hasko, V. (2013). Capturing the dynamics of second language development via learner corpus research: A very long engagement. The Modern Language Journal, 97(S1), 1–10.

- Ide, N., & Pustejovsky, J. (Eds.). (2017). Handbook of linguistic annotation. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- LINGUIST List. (2018). Texts and corpora. Retrieved June 16, 2018 from https://linguistlist.org/sp/GetWRListings.cfm?wrtypeid=1

- McEnery, A., Xiao, Z., & Tono, Y. (2006). Corpus‐based language studies: An advanced resource book. London, England: Routledge.

- Niekler, A., Wiedemann, G., & Heyer, G. (2017). Leipzig corpus miner: A text mining infrastructure for qualitative data analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv: 1707.03253.

- Rezvan, M., Shekarpour, S., Balasuriya, L., Thirunarayan, K., Shalin, V., & Sheth, A. (2018). A quality type‐aware annotated corpus and lexicon for harassment research. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.09416

- Schmied, J. (1993). Qualitative and quantitative research approaches to English relative constructions. In C. Souter & E. Atwell (Eds.), Corpus‐based computational linguistics (pp. 85–96). Amsterdam, Netherlands: Rodopi.

- Sinclair, J. M. (1996). EAGLES: Preliminary recommendations on corpus typology. Retrieved May 16, 2018 from http://www.ilc.cnr.it/EAGLES/corpustyp/corpustyp.html

- Timmis, I. (2015). Corpus linguistics for ELT: Research and practice. London, England: Routledge.

Suggested Readings

- Costa, A. P., Reis, L. P., de Sousa, F. N., Moreira, A., & Lamas, D. (Eds.). (2017). Computer supported qualitative research. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Friginal, E. (Ed.). (2017). Studies in corpus‐based sociolinguistics. London, England: Routledge.

- McEnery, A., & Baker, P. (Eds.). (2015). Corpora and discourse studies: Integrating discourse and corpora. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- McEnery, A., & Gablasova, D. (2017). Learner corpus research: New perspectives and applications. London, England: Bloomsbury.

Qualitative Research on Information and Communication Technology

PAIGE WARE AND MARK WARSCHAUER

Qualitative research on information and communication technology (ICT) covers a wide terrain, from studies examining the skills needed for reading, consuming, and producing information online to the communication practices taking place within social media and virtual environments. Rapid proliferation of ICT has fostered experimental studies examining a number of quantifiable outcomes associated with its uses, but qualitative research has built on our understanding of how, when, why, and for whom experiences with ICT shape participation, relationships, and learning. Researchers still have much to explore in order to understand what Shaw and Hargittai (2018) have described as the “pipeline of online participation” (p. 143). Persistent questions emerge about how the overlapping layers of Internet access, socioeconomic level, geographic location, educational background, privilege, position, and power might converge to create more opportunities for equitable participation in the online consumption, production, and sharing of knowledge. The methods provided by qualitative research provide the necessary analytical tools and theoretical frameworks to explore these emerging issues. This entry begins with an overview of three current areas of qualitative research on ICT and is then followed by a discussion of the methodological challenges of ICT research. Finally, new demands on qualitative researchers are explored.

Current Areas of Inquiry in ICT Research

Current work on ICT tackles research questions stemming from three main focal areas: (a) the skills needed for reading, consuming, and producing information for the Internet; (b) the factors impacting system‐wide implementation of ICT initiatives in schools; and (c) the affordances of network‐based interactions that take place across geographically distal contexts (for syntheses, see Suggested Readings).

Skills for Reading, Consuming, and Producing Information

ICT research examines the cognitive factors and online behaviors of individuals engaging with new technologies as they read, conduct research, and generate informational texts. Tools such as think‐alouds, retrospective protocols, screen capture, eye‐tracking software, and directed graphs are deployed to understand how individuals develop and make use of a range of online skills. Studies in this area have developed a knowledge base that outlines which skills individual users need to read and navigate online texts (Coiro & Dobler, 2007), to search for and process information from the Internet (Kuiper, Volman, & Terwel, 2005), and to orchestrate a dynamic interplay of reading strategies and meaning construction (Cho, 2014).

Two recent trends characterize this research area. First, more emphasis is being placed on the collaborative aspects of developing critical literacy skills. Forte (2015), in a series of qualitative studies on how high school students assess information when creating collaborative online texts, points to the growth in public online communication as shepherding in a “new class of information literacy skills” (p. 35). The key to this approach is the deliberate linking of two tasks that have traditionally been kept separate: assessing online information and producing a collaborative document on an open source. In this way, as consumers of information who are also engaged in the act of public production, individuals experience a different level of responsibility for their engagement.

A second trend is toward a focus on better pedagogical implementation. In its early stage, the focus in qualitative research in ICT was often on students, but, recently, researchers have examined the extent to which teachers themselves are prepared to teach explicit ICT skills. Particularly in light of recent experimental studies confirming an achievement gap in online reading skills based on student income (Leu et al., 2014), qualitative researchers are now examining teachers' skills and instructional strategies around effective, safe ICT use (Shin, 2015). Leu, Forzani, and Kennedy (2015) synthesized early findings of this research base to recommend a number of strategies that help teachers support online literacy skills, such as collaborative online research, reciprocal teaching, online exchanges, explicit modeling, classroom wikis and blogs, learning selectivity of sites, and building students' organizational skills.

Factors that Impact School‐Wide ICT Initiatives

As digital technology has become a ubiquitous presence in many schools, qualitative researchers have helped school leaders and teachers understand the factors that influence the successful uptake and use of ICT. A standard approach in these studies is to use cross‐case analysis to combine field observations, interviews, and artifact analysis to track, in broad strokes, the ways that technology is, or is not, leveraged in meaningful ways in different school contexts.

Qualitative work among applied linguists provides nuanced analyses of the types of literacy and language practices that take place in technology‐rich schools. In one of the first large‐scale investigations in a multi‐case study of 10 schools, Warschauer (2006) examined the skills, roles, and system‐wide changes that occurred when schools provided laptop computers for use by every student in one or more grade levels. He concluded that literacy processes, resources, and products changed markedly in laptop classes, resulting in more meaningful and student‐centered classroom practices. In a recent study exploring the impact of cloud‐based applications in laptop schools, Yim, Warschauer, and Zheng (2016) documented how such tools augmented the positive impact of such one‐to‐one programs because of the convenience, accessibility, affordability, and flexibility offered by cloud‐based networking. In the last 10 years, the findings from a number of studies on the impact of such one‐to‐one laptop initiatives has resulted in converging evidence that the overall effects are consistently positive (Zheng, Warschauer, Lin, & Chang, 2016).

Affordances of Network‐Based Interactions

Network‐based studies are conducted outside of a bricks‐and‐mortar context and examine issues that cross a wide range of inquiry, from research emerging out of intentional international projects that connect distally located partners, to studies of the naturally occurring interactions that take place on social networking sites and in MMO (massively multiplayer online) virtual gaming worlds. Participation in these networked spaces is typically defined by shared interests or goals, by an inclusive environment of novices and experts, and by a mixture of both individual and distributed knowledge.

In intentional international projects, language researchers and educators use a combination of triangulated data sources that include interviews, observations, discourse analysis, and text analysis to examine online communication in synchronous and asynchronous environments. These studies often differ in their focus and scope—different learner outcomes, task designs, modes of communication, learner populations, target languages, and sample size. They share, however, interests in understanding how language teaching and learning are changing in multilingual and multimodal environments, and how globalized notions of language, culture, and context intersect with local constraints of institutions and ideologies in new online realms.

Networked environments foster unique communicative affordances not readily available in traditional settings. A review by Thorne, Black, and Sykes (2009) documents how researchers examine linguistic and cultural aspects of virtual environments by using observations, in‐game chat logs, interviews, participant mapping, questionnaires, and journals. In a case study example of gaming, Rama, Black, van Es, and Warschauer (2012) explore the affordances of World of Warcraft to document how affordances were shaped by the participants' experience with the game, the cultural norms inside the game, and the basic game design.

In the context of an after‐school program for adolescent youth engaged in MMO gaming, Steinkuehler and King (2009) explored the connections among cognition, motivation, and mastery learning by analyzing data on participant observation, multimodal field notes, participant artifacts, interviews, videotaped interactions, and pre‐ and post‐test comparisons of student performance. Lam's work (2009) on youth participating in multilingual, transcultural online communities makes use of individual and focal group interviews, screen recordings of digital literacy practices, online transcripts, observations, and surveys to document mutually constitutive identity formation in online communities.

These examples reflect larger trends common to qualitative studies of communication practices on social networks. First, they involve a large investment of participant observation time to gain an insider, or emic, perspective—even in online contexts. Second, they move beyond concerns of language or literacy development in a conventional sense to instead focus on documenting the roles and functions of language as it is used in transcultural, transnational online settings. Finally, studies typically draw on and contribute to theoretical lenses that view literacy as multimodal and situated within larger institutional, social, and cultural discourses.

Considerations of Qualitative Methods in ICT Settings

Conventional qualitative data collection methods are commonly used in qualitative research on ICT, such as conducting interviews and observations, collecting field notes, amassing relevant documents, and disseminating surveys (Miles & Huberman, 1994). These methods, however, are based on face‐to‐face, physical settings and require new considerations in many ICT settings. Researchers committed to crossing, as Leander (2008) suggests, the “online/offline, virtual world/real world, and cyberspace/physical space binaries” (p. 37) must retool and repurpose these methods of data collection and analysis in order to capture interactions and information flows across digital as well as physical spaces.

Researchers must consider the interaction between the products of digital communication (interaction transcripts, Weblog archives, videos, Web sites, etc.) and the processes of the production and consumption cycle (access, orientation, affiliation, collaboration, interactivity, etc.). In practice, this translates into the creative addition of new data collection and analytic techniques. Archived data can include typical downloaded materials such as transcripts of synchronous chats and asynchronous posts, but they also extend to an array of new archives that layer in visual and aural modes: network analyses, social media communications, and screen capture data.

Researchers of social networking and gaming activities often gather transcripts and screenshots of the social interaction and activity that take place in various forums (online gaming, fan fiction, multilingual networking, instant messaging, listservs, chatrooms, and blogs) and triangulate this interactional information with other online activity, including participants' personal Web sites and updates, player manuals, and online guidebooks (see Black, 2008; Leander, 2008; Lam, 2009; Steinkuehler & King, 2009).

Examining the processes of ICT activity also presents new challenges in qualitative research because the local is no longer dictated by physical spaces. When participants are distally located—whether in naturally occurring interactions or in projects that involve international communication—researchers seek other ways to understand the perspectives and contexts of participants across wide geographic areas. To this end, interviews can be conducted utilizing e‐mail, listservs, instant messenging, and video conferencing.

A final consideration of qualitative methods in ICT is the continued enrichment of research in this field that is offered by its interdisciplinary flexibility and creative mixing of new ideas. Communication in ICT is increasingly multimodal and focused not just on transmission of ideas but also on meaning making across and within multiple sign systems. Stornaiuolo, Smith, and Phillips (2017) offer a transliteracies framework that foregrounds analytical tools that describe, and explicitly investigate, not just the material and social aspects of communication, but also the power relationships, normative assumptions, and multiple perspectives that surround interaction. This complex interplay of relationships is echoed in the concept of playscapes put forward by Abrams, Rowsell, and Merchant (2017), who argue that researchers must understand that these “entangled practices involve the interweaving of human, material, semiotic, and discursive practices” (p. 1).

New Demands in Qualitative Research in ICT

New demands are placed on researchers in the dynamic and expanding contexts in which ICT takes place within and across the multiple contexts of home, school, and Internet activity. Issues related to ethics, privacy, and expertise intertwine in ways that continue to require novel approaches.

First, conducting ethical research within ICT poses a number of new challenges. Busher and James (2015) explore these “ethical conundrums” (p. 178) that arise as the once‐separate domains of online communication and face‐to‐face contact have, in many contexts, become interlocking hybrid communities. To keep subjects safe and research findings trustworthy, Busher and James urge researchers to take additional steps—such as iterative reflection on ethical issues—at every stage of the study, not just at the inception. They also argue that the sites of research should not be framed as physical locations, but rather as multiple physical, multimodal, and social interactional spaces that people occupy.

Deepening qualitative inquiry will demand expertise beyond traditional methods and require time investment as well as a larger shift toward collaborative research teams that can make use of distributed expertise. Such collaborations have already been conducted in online intercultural communication projects, in which teachers and researchers design and implement studies across distally located sites (O'Dowd, 2015). Collaborative research has also taken place in single‐site ethnographic work, in which large teams of researchers conduct home and school visits on larger numbers of focal participants by using the same theoretical lens and framing questions (Leander, 2008). Research teams can address some of the practical issues that can become problematic, such as ensuring representation and coverage of an area of inquiry when the information needed is not conveniently located in one physical space.

Issues related to privacy also pose new challenges. In online‐only contexts in naturally occurring interactions, recruiting participants and obtaining informed consent can be challenging. Verification of participant identity is a challenge, which in Black's (2008) study on fan fiction was addressed by verifying participants' self‐described identity through triangulating information gleaned from self‐reports, consistencies in their presence in other areas of the Internet, and signed written consent. Privacy must also be established to protect individuals who might appear in the communication, but who are not themselves research participants (Busher & James, 2015). One plausible solution to this dilemma was provided by Lam (2009), who asked her focal participants to inform their online contacts about the research prior to recording any instant messaging sessions.

Leander (2008) documents further challenges associated with ethical online research, including maintaining the privacy of what he calls “incidental data” (p. 59), that is, interactions and activities documented by the researcher but which the participants might wish to exclude from viewing by others. Leander therefore employed a series of precautionary measures, including obtaining consent through Web‐based forms, allowing participants to view and delete sections of the transcripts of files before releasing them to the researchers, and developing longer‐term, collaborative relationships with the participants.

Conclusion

Qualitative research is ideal for exploring new realms in which there is little previous research. With technology‐mediated interaction developing so rapidly, qualitative research has been well suited to exploring ICT practices that occur in such realms, and will likely continue to be in the future.

SEE ALSO: Intercultural Interaction; Mobile‐Assisted Language Learning; Multilingualism and the Internet; New Literacies of Online Research and Comprehension; Teaching Culture and Intercultural Competence

References

- Abrams, S., Rowsell, J., & Merchant, G. (2017). Virtual convergence: Exploring culture and meaning in playscapes. Teachers College Record, 199(12), 1–16.

- Black, R. (2008). Adolescents and online fan fiction. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Busher, H., & James, N. (2015). In pursuit of ethical research: Studying hybrid communities using online and face‐to‐face communications. Educational Research & Evaluation, 21(2), 168–81. doi: 10.1080/13803611.2015.1024011

- Cho, B. (2014). Competent adolescent readers' use of Internet reading strategies: A think‐aloud study. Cognition & Instruction, 32(3), 253–89. doi: 10.1080/07370008.2014.918133

- Coiro, J., & Dobler, E. (2007). Exploring the online reading comprehension strategies used by sixth‐grade skilled readers to search for and locate information on the Internet. Reading Research Quarterly, 42(2), 214–57.

- Forte, A. (2015). The new information literate: Open collaboration and information production in schools. International Journal of Computer‐Supported Collaborative Learning, 10(1), 35–51. doi: 10.1007/s11412‐015‐9210‐6

- Kuiper, E., Volman, M., & Terwel, J. (2005). The Web as an information resource in K‐12 education: Strategies for supporting students in searching and processing information. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 285–328.

- Lam, W. S. E. (2009). Multiliteracies on instant messaging in negotiating local, translocal, and transnational affiliations: A case of an adolescent immigrant. Reading Research Quarterly, 44(4), 377–97.

- Leander, K. (2008). Toward a connective ethnography of online/offline literacy networks. In J. Coiro, M. Knobel, C. Lankshear, & D. J. Leu (Eds.), Handbook of research on new literacies (pp. 33–65). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Leu, D. J., Forzani, E., & Kennedy, C. (2015). Income inequality and the online reading gap: Teaching our way to success with online research and comprehension. The Reading Teacher, 68(6), 422–7.

- Leu, D. J., Forzani, E., Rhoads, C., Maykel, C., Kennedy, C., & Timbrell, N. (2014). The new literacies of online research and comprehension: Rethinking the reading achievement gap. Reading Research Quarterly, 50(1), 1–23. doi: 10.1002/rrq.85

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- O'Dowd, R. (2015). Supporting in‐service language educators in learning to telecollaborate. Language Learning & Technology, 19(1), 63–82. doi: 10125/44402

- Rama, P., Black, R., van Es, E., & Warschauer, M. (2012). Affordances for second language learning in World of Warcraft. Recall, 24(3), 322–38. doi: 10.1017/S0958344012000171

- Shaw, A., & Hargittai, E. (2018). The pipeline of online participation inequalities: The case of Wikipedia editing. Journal of Communication, 68(1), 143–68. doi: 10.1093/joc/jqx003

- Shin, S.‐K. (2015). Teaching critical, ethical, and safe use of ICT to teachers. Language Learning & Technology, 19(1), 181–97. doi: 10125/44408

- Steinkuehler, C. A., & King, E. (2009). Digital literacies for the disengaged: Creating after‐school contexts to support boys' game‐based literacy skills. On the Horizon, 17(1), 47–59.

- Stornaiuolo, A., Smith, A., & Phillips, N. C. (2017). Developing a transliteracies framework for a connected world. Journal of Literacy Research, 49(1), 68–91. doi: 10.1177/1086296X16683419

- Thorne, S., Black, R., & Sykes, J. (2009). Second language use, socialization, and learning in Internet interest communities and online gaming. Modern Language Journal, 93, 802–21.

- Warschauer, M. (2006). Laptops and literacy: Learning in the wireless classroom. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Yim, S., Warschauer, M., & Zheng, B. (2016). Google Docs in the classroom: A district‐wide case study. Teachers College Record, 118(9), 1–24.

- Zheng, B., Warschauer, M., Lin, C., & Chang, C. (2016). Learning in one‐to‐one laptop environments. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1052–84. doi: 10.3102/0034654316628645

Suggested Readings

- Coiro, J., Knobel, M., Lankshear, C., & Leu, D. (Eds.). (2008). Handbook of research on new literacies. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Kern, R., Ware, P., & Warschauer, M. (2016). Computer‐mediated communication and language learning. In G. S. Hall (Ed.), Routledge handbook of English language teaching (pp. 542–55). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Levy, M., Hubbard, P., Stockwell, G., & Colpaert, J. (2015). Research challenges in CALL. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28(1), 1–6. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2014.987035

Qualitative Sociolinguistics Research

JULIET LANGMAN AND PETER SAYER

Qualitative sociolinguistics research (QSR) is an approach that focuses on the ways in which people in communities use language to accomplish things in the world, and how they represent themselves to the world. QSR, in contrast to quantitative research, seeks to examine and explain the richness of language use in particular contexts with an overall aim of understanding the relationships between language and the social world. As such, qualitative sociolinguistics research employs a range of data‐collection and analytic tools and approaches that can lead to a “socially sophisticated approach to language variation that systematically takes into account the behaviors and motivations of speakers” (Chambers, 2003, p. 8).

Given the increasing complexity and interconnectedness of today's world, QSR places central importance on understanding how differences in language both reflect and help to create differences in, on the one hand, how individuals and groups use language, and, on the other, how they are evaluated or judged as a result of their language use by others. While QSR describes a particular research orientation, researchers in this area employ several related research methods, in particular ethnographic methods and discourse analytic approaches.

Formulating Qualitative Sociolinguistic Research

Qualitative research, by its name, implies a concern for the details and particularities of a research problem; in the case of sociolinguistic research, this entails a focus on the details and particularities of language use in context (Ramanathan & Atkinson, 1999). Key to any qualitative sociolinguistics research is a definition of language use and a definition of context. The concept of context can be understood in terms of a set of concentric circles of influence on a given language situation in which language is used for particular communicative functions. Beginning with the most local context, sociolinguists are interested in understanding how the moment‐to‐moment actions of one speaker in a particular time and place affect the form of what is said, the meaning that is intended, and the manner in which it is interpreted by others in the interaction. Social interactions are also framed by relationships among group members, which approaches such as social network analysis (Milroy, 1987) and communities of practice (Eckert & McConnell‐Ginet, 1992) take as their starting point. Discerning and explaining differences in how language use both creates and reflects social groupings lies at the heart of sociolinguistics research. Through careful in‐depth analyses of a wide range of situations and associated language uses, a picture of how language works to structure society, and human relations within it, can be drawn.

QSR, like all other forms of research, starts with a particular question or issue. Consonant with the field of sociolinguistics, the research question or issue typically focuses on a social concern: for example, understanding how individuals argue and misunderstandings occur, understanding how children and adults acquire the tools to communicate in their own or in new communities, or understanding how particular contexts serve to support or hinder individuals with different language practices when it comes to achieving their communicative and social goals. Topics or areas of concern in the last 20 years have included differences in interaction both within groups and between members of groups based on social class, race, ethnicity, and gender; bilingualism, code switching, and translanguaging; language planning and language policies; and educational and workplace practices. In each of these cases, research also often attempts to understand and explain inequality in terms of how individuals' language is evaluated.

Traditions in Qualitative Sociolinguistics Research

The use of qualitative methods in sociolinguistics generally belongs to one of three related approaches. The first derives from Dell Hymes's (1974) formulation of the ethnography of communication (also called the “ethnography of speaking”). The second is John Gumperz's (1982a, 1982b) work in the area of interactional sociolinguistics (see also Gumperz & Hymes, 1972). The third approach examines language socialization processes and focuses on the development of language use appropriate to a given community (Schieffelin & Ochs, 1986).

Hymes, coming from the tradition of linguistic anthropology, was interested in understanding how speakers accomplish social goals in given social situations in particular speech communities. His contributions include the concept of communicative competence and the characterization of language use in nested contexts, namely, speech situation, speech event, and speech act. In addition, Hymes introduced the SPEAKING model as a mnemonic (Setting and Scene, Participants, Ends or goals, Acts, Key, Instrumentalities, Norms, and Genre) for examining all aspects of speech events that affect the form language takes and the associated language and social functions it fulfills. This model, moreover, provided qualitative researchers with a methodological tool or a frame for focusing on data to collect, and allowed for systematic and easily comparable analyses of situated language practices with a particular focus on the macrolevel of social situations and settings in which language is used (Copland & Creese, 2015).

Seminal works in the ethnography of communication tradition include Philips's (1983) study of how language differences between Warm Springs Indian and Anglo children in schools—for example, the organization of interactional sequences and the use of silence—often made Anglo teachers perceive Native American children's behavior as reticent or noncommunicative rather than polite and deferential, as the students intended. Likewise, Heath's (1983) study of the literacy practices of three social groups revealed how values associated with particular language practices are socially constructed according to cultural norms and expectations. Eckert (2000) blended qualitative and quantitative methods to study the social structure of a typical high school. Her description and analysis of student cliques, “jocks,” and “burn‐outs” allowed her to demonstrate how language serves to structure social groups. What these studies have in common is their connection to the roots of ethnography: long‐term participant observation in order to come to an understanding of language use from an insider (emic) perspective.

The second research tradition—interactional sociolinguistics established by John Gumperz (1982a, 1982b)—focuses on the face‐to‐face immediate context of interaction with the goal of understanding how each turn at talk influences subsequent turns at talk in ways that link any particular conversation to broader social categories. Such microlevel analyses of language use allow researchers to trace the linguistic and associated social origins of tensions that may exist across speakers that reflect broader patterns of inequality and that can lead to miscommunication. For example, Gumperz (1982a) analyzes how Indian and British participants in three short conversations had radically different perceptions of the attitudes and intentions of the Indian participants, based on the intonation patterns they used in simple questions: While the Indians intended to convey respect and deference, the British perceived their interlocutors as “surly and uncooperative” because the communicative value of rising as opposed to falling intonation patterns on simple questions are reversed for speakers of these two different English‐speaking speech communities. While this perspective focuses on a careful analysis of the linguistic form, it further requires the researcher to link the analysis of language features such as intonation to socially defined relationships between speakers.

Research from a language socialization perspective (Ochs & Schieffelin, 1984; Schieffelin & Ochs, 1986; Ochs, 1988) also examines language in use contextually and qualitatively, drawing on work from linguistic anthropology. Here the primary focus of research is on how individuals—in particular children in their native communities—come to use language appropriately (i.e., in line with community norms). This strand of research is cross‐cultural and also rests on the tradition of ethnographic observation and careful analysis of interactions, primarily caregiver and young child interactions. Such work, recently extended to include a focus on life‐long socialization into new communities, focuses on how individuals come to be “speakers of culture” (Ochs, 2002).

Observing Language Use in Context

To engage in qualitative sociolinguistics research means to spend time carefully observing and analyzing language in context in order to understand the language practices of individuals, the motivations or intentions underlying those practices, and how these language practices relate to society's norms or expectations about language. Johnstone (2000) traces this tradition of documenting language use to the field methods used by dialectologists in the 19th century who were interested in describing the linguistic characteristics of speakers of regional varieties. In contrast to quantitative sociolinguistics research, qualitative sociolinguistics research involves in‐depth and often long‐term observation of individuals and groups interacting naturally in society. Whereas a researcher using quantitative methods may use statistical correlations to show, for example, the complex connections between gender and social groups, a qualitative researcher may approach a similar question by analyzing both routine practices and “telling” examples to demonstrate how language constructs identity. For example, Ek (2009) analyzes how a young Guatemalan American woman negotiates her identity in contexts (home, church, and school) that represent and structure conflicting expectations with respect to ethnicity and gender. While quantitative researchers' data and analyses address questions of how often or how much a particular language practice occurs and is associated with social groupings, qualitative analyses are better suited to questions of how and why people engage in these practices (Johnstone, 2000).

Issues and Tools in Data Collection

There are several important issues related to collecting data on people's language practices. The first applies to both quantitative and qualitative methods, and was recognized early on by sociolinguist William Labov as the observer's paradox. The dilemma arises from the fact that language use is highly situated and dependent both on speakers' perceptions of what their interlocutors know and need to know, and on how they wish to present themselves to their interlocutors. Therefore, when an observer enters the social scene, their presence changes the dynamic of how speakers use language, and data (language practices) are altered simply because the observer is there to record them. For example, if participants perceive the researcher as an outsider, they will likely adjust their speech, by simplifying their grammar and lexis (foreigner talk), or by altering the form or content of what they say in subtle ways to accommodate the researcher's presence. This might affect the production of exactly the kinds of in‐group linguistic markers or expressions of shared understandings that sociolinguists are interested in documenting.

There are several ways of counteracting the effect of the observer's paradox. Consonant with ethical issues related to working with human subjects, the preferred method is to be forthright about the purpose of the study, and to spend enough time interacting with people in the research setting so that the researcher's presence becomes familiar and participants' language use reverts mostly to what it would have been before the researcher arrived. This method, however, generally presupposes long‐term engagement with the community, and does not resolve the observer's paradox as much as require researchers to locate themselves in the study and recognize that they have become part of the social scene they are investigating. Likewise, if researchers study a group of which they are already members or “insiders,” they will have better direct access to the group's unfiltered language practices, though their insider status may cause other issues for their ability to analyze and interpret the data.

The tools for collecting qualitative sociolinguistic data are relatively straightforward: researchers generally rely on observation or participant observation supported by some combination of questionnaires, interviews, field notes, and recordings. The questionnaire or survey is a common instrument in both quantitative and qualitative studies since it can efficiently gather a large number of responses in a short period of time. The responses are easy to tabulate and present a straightforward set of results. Qualitative surveys often include Likert‐scale (e.g., a five‐point scale indicating agreement with a particular statement) and some open‐ended items (Dörnyei, 2003). The limitation of questionnaires for language research is that they measure linguistic perceptions or beliefs rather than actual language practices, and include unrecorded adjustments to those perceptions based on the concept of the observer's paradox. It is also deceptively difficult to design good questionnaire items that will be interpreted in the same way by all respondents.

The sociolinguistic interview (Becker, 2013), like the survey, gathers elicited data by directly posing questions to participants. While interviewing is not as efficient as questionnaires, good interviewing techniques can yield rich insights about participants, in particular regarding their own attitudes and perspectives on language use in the particular context under study. Field notes and recordings both serve to document naturalistic data, that is, in situ language practices that are not directly elicited by the researcher. Taking field notes is a common practice in ethnography and is unobtrusive, although researchers are restricted by how much they can write down and are not able to go back and recheck the accuracy of their notes. Audio and video recordings have the advantage of allowing researchers to transcribe interactions and gain a fuller picture of language use. However, recording devices can be obtrusive—although less so today in many contexts, with digital devices so prevalent and much smaller in size. Nonetheless, as with all other forms of data collection, recording equipment always both focuses and therefore limits the data that can be gathered for analysis.

Recent Trends in Qualitative Sociolinguistic Research

Since the late 1990s, a number of new approaches to qualitative sociolinguistic research have emerged, each stemming from the traditions outlined above, but drawing new insights from theorizing and research in related fields. Most notable is the influence of sociocultural theory and, in particular, the community of practice model from cognitive science (Lave & Wenger, 1991), which has been taken up to examine language practices (Bucholtz, 1999; Eckert, 2000). With the introduction of this perspective a number of concepts, originally part of the work of either Hymes or Gumperz, have received greater attention. In particular, with the introduction of the community of practice as an alternative to the concept of the speech community, the concepts of identity, ideology, and power have led to a shift in focus from understanding the normative behavior of individuals in groups to examining language practices at the margins, that is, language practices that individuals engage in to resist, subvert, or change community‐wide practices. These studies examine the ambivalence, tensions, and contradictions that define intragroup as well as intergroup differences (Rampton, 1999). Furthermore, there is an increased interest in the sociolinguistics of multilingualism (Bell, 2014). The multilingual focus stems from the recognition that many of original questions and the face‐to‐face encounters that traditional sociolinguistics analyzed are increasingly happening in complex multilingual, multimodal, and even digital spaces (Horner & Weber, 2018).

Recent work has moved away from a normative or essentialist view of language practices and aims to examine and explain the multiple and fluid ways in which language is used by particular groups of people in particular contexts. One such recent focus centers around the concepts of superdiversity (Arnaut, Blommaert, Rampton, & Spotti, 2015) and translanguaging (Otheguy, García, & Reid, 2015). These two concepts expand the concept of language to focus on language practices of multilinguals, and the concept of context as one characterized by multilingual language use. Nevertheless, these new approaches continue to employ the core data‐collection techniques and insights from earlier research, while at the same time incorporating a different range of theoretical frames for analysis, frames that draw on a critical perspective of how language and society mutually structure one another.

In addition, there is a caveat worth noting with respect to the “quantitative versus qualitative” distinction: since the mid‐1990s, following criticisms by variationist sociolinguists as well as anthropological linguists on work grounded in a single tradition, combined or mixed‐methods approaches have emerged, which aim to provide richer explanations of observed differences in language use among members of communities under study. Those richer explanations, coming from a more in‐depth examination of social contexts in which language use occurs, have been referred to as the third wave in sociolinguistic research (see Eckert, 2008).

SEE ALSO: Anthropological Linguistics

References

- Arnaut, K., Blommaert, J., Rampton, B., & Spotti, M. (2015). Language and superdiversity. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Becker, K. (2013). The sociolinguistic interview. In C. Mallinson, B. Childs, & G. Van Herk (Eds.), Data collection in sociolinguistics (pp. 91–100). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Bell, A. (2014). The guidebook to sociolinguistics. Malden, MA: Wiley‐Blackwell.

- Bucholtz, M. (1999). “Why be normal?”: Language and identity practices in a community of nerd girls. Language in Society, 28, 203–23.

- Chambers, J. (2003). Sociolinguistic theory: Linguistic variation and its social significance. Oxford, England: Blackwell.

- Copland, F., & Creese, A. (2015). Linguistic ethnography. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Dörnyei, Z. (2003). Questionnaires in second language research. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Eckert, P. (2000). Linguistic variation as social practice. Oxford, England: Blackwell.

- Eckert, P. (2008). Variation and the indexical field. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 12, 453–76.

- Eckert, P., & McConnell‐Ginet, S. (1992). Think practically and act locally: Language and gender as community‐based practice. Annual Review of Anthropology, 21, 461–90.

- Ek, L. (2009). “It's different lives”: A Guatemalan American adolescent's construction of ethnic and gender identities across educational contexts. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 40(4), 405–20.

- Gumperz, J. J. (1982a). Discourse strategies. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Gumperz, J. J. (Ed.). (1982b). Language and social identity. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Gumperz, J. J., & Hymes, D. (Eds.). (1972). Directions in sociolinguistics: The ethnography of communication. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Heath, S. B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and classrooms. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Horner, K., & Weber, J.‐J. (2018). Introducing multilingualism: A social approach (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hymes, D. (1974). Foundations in sociolinguistics: An ethnographic approach. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Johnstone, B. (2000). Qualitative methods in sociolinguistics. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Milroy, L. (1987). Language and social networks (2nd ed.). Oxford, England: Blackwell.

- Ochs, E. (1988). Culture and language development: Language acquisition and socialization in a Samoan village. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Ochs, E. (2002). Becoming a speaker of culture. In C. Kramsch (Ed.), Language acquisition and language socialization: Ecological perspectives (pp. 99–120). London, England: Continuum.

- Ochs, E., & Schieffelin, B. B. (1984). Language acquisition and socialization: Three developmental stories. In R. Shweder & R. LeVine (Eds.), Culture theory: Essays on mind, self and emotion (pp. 276–320). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Otheguy, R., García, O., & Reid, W. (2015). Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review, 6(3), 281–307.

- Philips, S. U. (1983). The invisible culture: Communication in classroom and community on the Warm Springs Indian Reservation. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

- Ramanathan, V., & Atkinson, D. (1999). Ethnographic approaches and methods in L2 writing research: A critical guide and review. Applied Linguistics, 20(1), 44–70.

- Rampton, B. (Ed.). (1999). Styling the other (Special issue). Journal of Sociolinguistics, 4(3).

- Schieffelin, B. B., & Ochs, E. (Eds.). (1986). Language socialization across cultures. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Suggested Readings

- Saville‐Troike, M. (2003). The ethnography of communication (3rd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Schecter, S. R., & Bayley, R. (2002). Language as cultural practice: Mexicanos en el norte. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Zentella, A. C. (1997). Growing up bilingual. Oxford, England: Blackwell.

Quantitative Methods

HOSSEIN FARHADY

Introduction

There has been a plethora of ongoing debates in the field of applied linguistics on many aspects of quantitative research method (QRM) in the last few decades. Despite the validity and significance of the debates and their contribution to sharpening our understanding of the concepts, QRM remains one of the most widely practiced approaches in social sciences in general, and in applied linguistics in particular (Lazaraton, 2005; Mackey & Gass, 2016). Although such debates are important and necessary, this entry will focus on explaining the major features of QRM in as nontechnical terms as possible.

Most scholars would agree with the classic definition of the term “research” as a systematic approach to answering questions (Hatch & Farhady, 1982, p. 1). There are three key terms in this definition: a question, a systematic approach, and an answer. The controversies in the field center not on the definition of the term “research” but on different interpretations of the key terms in the definition. For instance, the nature of the question and the way it should be formulated, the approach to be taken to answer the question, and the quality of the answer to the question are all issues upon which no wide agreement exists among scholars. The differences in the interpretations of these concepts stem from different theoretical orientations that scholars adhere to because advocates of each theory believe in a number of assumptions that justify their interpretations (Kinn & Curzio, 2005). Therefore, to put the issue in an appropriate context, first an explanation of the theoretical assumptions of QRM is given and then a description of how the three key terms in the definition function in practice is discussed.

Theoretical Assumptions

Generally, an inquiry is performed within a particular school of thought commonly referred to as a paradigm. This paradigm is believed to have four cornerstones: ontology, epistemology, methodology, and axiology (Onwuegbuzie & Leech, 2003; Creswell, 2007; Lochmiller & Lester, 2017). There are several popular paradigms such as positivism, constructivism, and relativism, each with some axiomatic principles that scholars follow, or should follow, in practice. Since QRM is rooted in the positivistic paradigm, a brief definition of the key concepts and their treatment in this paradigm will help clarify the characteristics of QRM within this framework.

Ontology raises questions about the nature of reality and the nature of human beings in the world. According to positivism, there is a real world, the reality of which is expressed in terms of the relationships among variables, and the extent of these relationships can be measured in a reliable and valid manner using a priori operational definitions. Positivists believe in the verifiability principle, which states that something is meaningful if and only if it can be verified by direct observation. Thus, ontologically, positivism is a school of thought that focuses on observable and measurable phenomena and their interrelationships.

Epistemology asks how we know the world and what the relationship between the inquirer and the known is. Epistemologically, positivism places a premium on objective observation of the “real world” out there. Positivists contend that the researcher (i.e., knower) and the object of the study (i.e., known) are independent. As such, researchers should remain objective and impartial in studying phenomena (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2011).

Methodology focuses on the best means of acquiring knowledge about the world. Methodologically, positivists use deductive reasoning which is a system for organizing known facts in order to reach a conclusion. Conclusions are true only if the premises upon which they are based are true. That is, positivists emphasize the importance of a priori hypotheses and theories. The researcher manipulates at least one variable and then measures its effect on another variable, controlling potentially extraneous variables. Through such a procedure, valid cause–effect relationships are believed to be established and generalized as laws.

Axiology deals with the ethics and asks how moral a person, a researcher, should be in the world. Every ontology or epistemology has its own ethical stance toward the world and the self of the researcher. Positivists believe that inquiries should be value free. In other words, the researcher's values, interpretations, feelings, and musings have no place in the positivist's view of scientific inquiry. Positivists prefer rhetorical neutrality, involving an exclusively formal writing style using impersonal voice and specific terminology.

Putting the above‐mentioned principles together, a working definition for QRM can be formulated as an inquiry where an impartial researcher investigates cause–effect relationships between the variables in a world of real objects. This derived definition conceptually matches textbook definitions where scholars contend that in QRM numerical data are collected on the variables and analyzed using mathematical methods (Aliaga & Gunderson, 2006). Following this definition, the three key concepts of “question,” systematic approach, and “answer” in QRM will be detailed below.

Formulating the Research Question

QRM starts with a question which is formulated about the relationship between at least two variables. A variable is any attribute that changes from person to person (height), place to place (size), or time to time (temperature). Variables can be concrete, that is, directly observable and measurable such as height and weight; abstract, that is, not directly observable or measureable but inferred from observations and measurements such as intelligence and language ability; discrete or categorical, that is, either/or type such as left or right handedness, male or female; and continuous, that is, can take any value such as weight and language ability. Research questions can be formulated about the relationship between the variables to indicate either a cause–effect relationship or just togetherness between them:

Example 1: What is the effect of using multimedia tasks on the learners' listening comprehension (LC) ability?

Example 2: What is the relationship between the students' LC and reading comprehension abilities?

The first question is of a cause–effect type where the researcher sets out to investigate whether using multimedia tasks will have any effect on the learners' LC ability. The second question, however, is of correlational type where the researcher intends to find an existing relationship between the two variables. No instruction or manipulation is planned to find a cause–effect relationship since the researcher appears on the scene after the fact and has no role in changing any one of the variables.

An important point in formulating a research question is defining the variables under investigation as clearly as possible in both theoretical and operational forms. To provide a reasonable theoretical definition, an in‐depth review of literature needs to be performed. Operational definition, on the other hand, is to suggest a clearly measurable procedure for the variable in question. For example, LC ability may be defined theoretically as the ability to understand oral messages in real‐life situations, and operationally as one's performance on a test which is designed to measure one's ability to understand oral messages.

Theoretical and operational definitions of a variable given in a particular research context may not be acceptable to all readers because they are specific to that research design. For instance, there may be different definitions of LC ability in theory and different measures of LC in practice. However, a working definition should be provided by the researcher that is most reasonable in the context of research. Despite the potential disagreement among scholars, it is an advantage of QRM that the researcher and readers share common definitions of the variables.

In addition to defining the variables, the researcher should determine the functions that variables are designed to serve in the process of research. Most common functions that a variable can serve in QRM are: independent, dependent, moderator, control, intervening, and extraneous. An independent variable is the main or the cause variable which is under the control of the researcher to be manipulated, while the dependent variable is the variable that depends on, or changes as the result of, the manipulation of the independent variable. For instance, in the example above, using multimedia tasks is the independent variable and performance on a measure of LC ability is the dependent variable because performance on this measure depends on the quality, quantity, and effectiveness of the multimedia tasks designed by the researcher.

A moderator variable is the variable that may influence the outcome of the dependent variable without being necessarily manipulated. For instance, within the context of this example, the researcher may hypothesize that males and females may benefit differentially from the multimedia instruction. In such a case, gender, as a moderator variable, may change the outcome of research. A control variable, on the other hand, is a variable whose effect is controlled or eliminated by the researcher so that the variation of this variable does not influence the outcome of research. Suppose the researcher believes that familiarity with computers may have an effect on the achievement and performance of the learners. Therefore, to control the effect of familiarity with computer, the researcher selects participants who are absolutely unfamiliar, or equally familiar for that matter, with computer technology. In this case, any effect due to computer familiarity is removed from the research design, that is, controlled.

An intervening variable is the variable that intervenes between the independent and the dependent variables. It is often left unobserved and unmeasured because it is very often an abstract variable. In our example, due to the effect of the independent variable, that is, multimedia instruction, the participants learn and improve their LC ability. Although this learning process can neither be observed nor measured, its effect is manifested in the measurement of the performance on an LC test. In other words, the learning process is situated between the independent and the dependent variables and intervenes with the outcome of the research without being observed or measured. And finally, an extraneous variable is a variable whose presence is neither observed nor accounted for in the research design. Such variables may influence and contaminate the outcome of research without the researcher's awareness. In the example above, many variables such as age, educational background, learning style, motivation, and so forth may have some effect on the students' learning. In short, any variable that is not controlled by the researcher and may influence the outcome of research is called an extraneous variable.

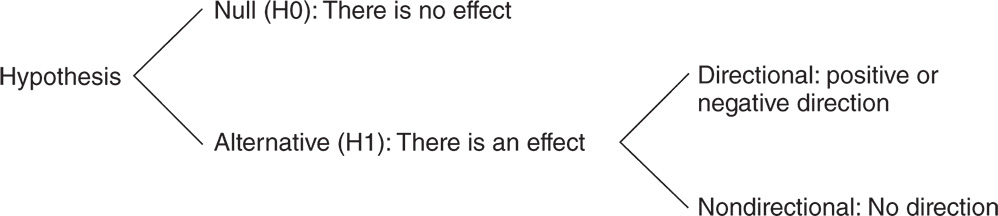

Figure 1 Forms of hypothesis

When the research question is formulated with well‐defined variables, it is converted into a research hypothesis to be tested. A hypothesis is a tentative statement about the outcome of research and can take two forms: null and alternative. A null hypothesis, symbolized as H0, is generally stated in the form that the manipulation of the independent variable will not have an effect upon the dependent variable. The alternative hypothesis, on the other hand, symbolized as H1, stipulates an effect, either positive or negative, of the independent variable on the dependent variable. For instance, null and alternative hypotheses for the example above would be:

| Null H0: | There is no relationship between using multimedia tasks and improvement in LC ability, or

Using multimedia tasks will not have any effect on the improvement of LC ability |

| Alternative H1: | There is a positive/negative relationship between using multimedia tasks and improvement in LC ability, or

Using multimedia instruction will have a positive or a negative effect on the LC ability of the participants. |