4

The Cult of Brand Belief

Every culture features its own brands—if you can even recognize them. I’ve rented a flat in Spain on Airbnb, and I need to buy a bottle of bleach. Problemo: no hablo español. I squint and scan the shelves looking for brands I recognize—Domestos? Clorox? Nope. I look for packaging that seems similar to bleach I’ve bought in the past—bottle shapes, colors. Useless. Finally, I pull out my iPhone, look up the Spanish word for bleach, and start reading labels. The whole process takes four times longer than merely grabbing what’s familiar. Guilt sets in. I probably shouldn’t even be using bleach, but a more environmentally sensible alternative. I end up buying the cheapest bottle and walk out feeling uneasy. Imagine every purchase decision taking this much time, and with so little conviction on the buyer’s part.

A world without familiar brands is an alien place. Imagine a supermarket with no labels on any of the products. Now put the labels back on, but no brands. How much reading would you need to do to find what you need? This is the simple reason that brands are here to stay. And they’re about to become more important than ever.

Our brains are designed to filter and forget. It’s been said that if we remembered every detail of everything we encounter, we’d go insane. We simply aren’t capable of remembering all the details of our life experiences, just as we don’t remember every dream we have. But we do remember people, faces, identities. We develop rich associations and allegiances based upon the totality of experiences shared. I may not remember a single aspect of every experience I’ve shared with my best friend, but I see her and I feel great affection. It is much the same with brands. They are summations, an easy-to-recognize shorthand.

Brands have become much more than a shorthand for price and efficacy, although those are indeed part of the picture. Today, brands trigger feelings, which are our gut response to the sum of everything we have learned, experienced, heard, and know about a particular company. Brands are the best means of securing emotional attachment to business (or place, or political movement, or whatever the sector is). And given that it’s been estimated that 80 percent of decision making is ultimately emotional, while 20 percent is rational, managing the emotional magnetism of your brand is your most important, value-creating business process.

This is because citizens of Conscience Culture wear their values on their sleeves—and carry them in their pockets, slip them into their tablet cases, fill their baskets with them at the market, download them to their smartphones, and post about them on social media. The values they uphold are signified and expressed through the brands they choose, use, promote, and join as employees.

Show me the brands you most love and use, and I’ll tell you who you are. Apple or Android? Coke, Pepsi, or neither? BMW or Chevy? Brands are amazingly efficient and effective shorthands for richly detailed belief systems with which we either want to self-identify or outwardly reject. The brands we choose, wear, use, talk about, wish we could afford, avoid—they all represent aspects of who we are; what we believe, value, and trust; and how we want others to see us.

“Belief systems?” you wonder, raising an eyebrow. “Isn’t a brand merely a signpost for the product or service itself?” Short answer: yes, if it’s not a resilient brand. In the Conscience Economy, there will be no place for brands that don’t sum up a set of relevant, inspiring beliefs. Even branded bleach. “But bleach is bleach,” you retort. Well, what about a bleach brand that is highly vocal about protecting the groundwater supply and offers a more environmentally sensible means of disposal, is packaged sustainably, and demonstrates on its packaging and in its communications how killing germs fights disease, while its manufacturer actually supports and visibly helps to fight disease by supporting a range of health-related social enterprises? In effect, it’s a bleach brand that engages with the Culture of Conscience.

After all, when we’re given two similar options at a reasonably comparable price, we don’t decide between products or services, we decide between brands. And when we make our choice, it’s not because we like the signpost itself, it’s because we value and align with all that it stands for, and increasingly, how it contributes to helping make the world as we’d like it to be.

The brands we like and want to be seen using are a means of identifying ourselves, our affiliation with others who like the same brand, our beliefs, what we value most. Brands are also who we work for and how we build our careers. A “good CV” is not only a history of the roles you’ve played; it’s the quality and prestige of the brands for which you worked. Political parties, social movements, places, transportation solutions, exercise regimes—it’s hard to think of a category of everyday life that isn’t branded.

The proliferation of purchase choice is not the only reason strong branding should be foremost on the agenda for any organization today. The rise of a new set of purchase decision-making priorities makes it even more crucial. It is increasingly difficult to part with our money without at least a glancing consideration as to its impact on the wider world. “Every dollar you spend is a vote for something,” proclaims a social entrepreneur, one of the founders of Project Provenance (provenance.it) an online marketplace that provides information transparency about new products, “so why not use that vote for something you believe in?”

Ignoring the consequences of our actions and purchases on the lives of others—and on the planet—will become harder and harder to do as real-time and contextually delivered information increasingly clarifies what those consequences are. It’s like product labeling on steroids—except that the “ingredients” we’ll see will be filtered to show what matters most to us, whether it’s ethical production processes, the political biases and donation histories of executives, or the environmental and societal implications of a company’s farms or factories. And the likelihood is, people will reject those products or services that are in some way contributing to issues they don’t support.

And, of course, while we have more choice, we’ve never had less time to exercise it. We need shortcuts. In an increasingly chaotic and fluctuating business environment, brands will be ever more important navigation devices for us all. They will sum up all that we do to make the world better for everyone. They are more than our calling cards. They are the definition of who and what we are, and they are the building blocks of the world we want to bring into being. Your customers need you to make it easy for them to recognize that what they care about is inherent in your products, your services, and even your mode of operation. Building and managing a robust brand has never been more vital for success.

Put simply, to stand out, you have to stand for something. To stand out in the Conscience Economy, you must position your business and brand as an emblem of all that the emergent culture holds dear. Indeed, your brand is the most potent business asset you can manage, because it sums up, contains, and conveys all that you are and will be.

Brand Begins Within

Sadly, the word “brand” is one of the most misunderstood and misused words in business. Too often, it’s thought of as what’s on the outside. A mere skin. A logo, a color scheme, and some communications design guidance written up in a tidy document by people in the marketing department.

The misconception is somewhat forgivable, given the etymology of the term. Originally, as you no doubt know, branding was all about skin—cattle skin, to be precise. As variously owned business assets (cows) mingled on the plains, there had to be some way of identifying their owners.

The origin of the word is apt today. Products and services mingle on the plains of the global marketplace, and we need some way of knowing where they came from, to whom they belong, who produced them and how, and why we should adopt them into our lives.

What’s more, we also need to know to whom we belong when we buy, invest in, or work for a brand. We don’t just acquire the hard asset. We join the cult. We become a part of a group of like-minded people who are fans of the same brand. It’s not dissimilar to being a fan of a particular sports team. There is a strong self-identification between people and the brands they love. In some cases, the careful discernment is as pragmatic as it is emotional, because once we’re “in” the brand’s ecosystem (hello, Apple) it can be hard to switch. Brands are a kind of mirror. We look for the reflection of our own values and dreams in the things that we buy.

Today, brands stand for how a product was produced, how the company operates, how it treats its people. Brands even stand for how a company positions itself with regard to politics. Pasta maker Barilla, for example, had an uncomfortable wake-up call when in 2013 its CEO made remarks perceived to be disparaging of same-sex relationships, triggering a mass boycott that swiftly went viral on social media.

Think about this for a moment. Because it’s pretty astonishing. The political biases of a company executive—especially when they’re perceived as extreme—can and do directly impact brand reputation, and consequently, sales, both positively and negatively. Brands like Chick-fil-A or television properties like Duck Dynasty have been battlegrounds for what we might call “conscience wars” between entrenched and polarized points of view on contemporary social issues.

Thus, powerful, magnetic branding is not what’s on the surface. It’s not decoration or dress-up. Those visually and aurally recognizable aspects of identity are merely brand signifiers. And when your company doesn’t live up to the meaning that it signifies, people see right through it.

A strong brand starts deep within the business. It’s more like the brain, the conscience of the organization. “Off brand” means wrong, “on brand” means right. If I may get a bit metaphysical or at least metaphorical, your brand is your company’s soul.

Perhaps because the very concept of brand is somewhat abstract and conceptual, it’s not unusual for it to be off-loaded to a creative team rather than discussed by all. To do so is a mistake. Because building and securing your brand by engaging all functions of the organization in the process, employing both left and right brains, is your company’s most powerful way to reaffirm or rethink its purpose, future strategy, and market position.

In a brand-centric business, every decision is made based upon the values, intentions, and aspirations of the brand. And not by consulting a framework or manual, mind you. When the brand is continuously reinforced through rituals of company culture, and when everyone is continuously engaged in talking about and applying the brand to everyday work, it becomes internalized in each employee. To shamelessly misappropriate from Adam Smith, your brand can and should be the business’s “invisible hand,” steadily guiding innovation, daily operations, protocols, and conduct.

Conscientious Brands

As enlightenment becomes ever sexier, those brands that manifest socially and environmentally sensible ways of operating will be the winners. Why else would Walmart begin enforcing greener production standards in China, or Apple and the NFL put themselves on the front lines of a political debate about gay rights in Arizona? Today, the most overtly conscientious brands include “goodness-certified” products (green, Fair Trade, cruelty free, for example), handmade and artisanal products, ethical luxury, ethical fashion, hybrid automobiles, and one-for-one products. But they also include retailers that vocally support causes and put their money where their PR is, those with conscientious worker policies and conditions. In the U.K., the John Lewis Partnership, with its department stores and supermarkets, is thought of as more than big business or a stable of retail brands; it’s a much-loved national institution, a cornerstone of British life, among those of all political persuasions.

What might the next set of brands dominating a new economy rooted in conscientiousness look like? How might we imagine new brands that are positioned to thrive and lead in a world where doing good matters as much as doing well?

Imagine if all the brands you used inspired you to be a better you in one way or another. What if, by choosing a particular product or service, you knew you were participating in progress in ways that are synchronized with your own values? The next wave of leading brands will be those that stand for a positive impact on humanity and the environment, in their own operations as well as through us, their buyers and users.

Every brand makes a promise. In the past, brands promised basic benefits like convenience, efficacy, style, speed, flavor, low cost, quality engineering, sex appeal, happiness, or luxury. Over time, and as technology has entered every aspect of our lives, brands have evolved to stand for more empowering personal capabilities like creativity, imagination, innovation, communication, playfulness, achievement, and collaboration. Conscientious brands will take the evolution further. In the Conscience Economy, the brands people most value and love will…

- Make us not only smarter but wiser.

- Empower us to solve our toughest challenges.

- Enable us to help others grow.

- Help us be physically and emotionally healthy.

- Defend our physical, financial, and environmental safety.

- Heal rifts and conflicts.

- Enable us to fix, restore, and remake stuff.

- Protect us from overexposure.

- Help us disconnect from the chaos of life.

- Empower us to make the world more beautiful, fun, and friendly.

- Help us save energy and resources.

- Facilitate sharing.

- Bring us closer to nature.

- Guide us to places, things, and people that inspire us.

- Deepen our connections with no compromise of privacy.

- Bring out the best in humanity.

Old and New Basics

In the Conscience Economy, it is not only the brand promise that shifts. As people’s expectations change, the basic principles for customer understanding and belief change, too. The old basics of rational and emotional benefits now include an overarching demand for personal agency, self and community empowerment, and positive social and environmental impact.

It’s not enough to focus on what your product does or even how it makes someone feel for buying it. It is now equally essential to focus on where and how it was produced. For example, you no longer just buy a coffee. You buy a Rainforest Alliance–certified, organic, small-batch roasted, and custom-built pumpkin latte that’s handcrafted and drizzled with caramel right in front of your eyes—at McDonald’s. The provenance of the coffee beans makes us feel in the know, and the customization makes us feel special. Already, the production story behind a product—whether it’s a cup of coffee, a microbrewed beer, or a sweater—is perhaps the most significant selling point among the international cohort of influential, young-minded, early-adopter customers who inhabit cities that lead the way for the mainstream, like San Francisco, Toronto, Barcelona, and even Beijing.

It’s also no longer enough to instigate mere product desire. It’s essential to invite a desire to participate in something bigger. For example, if you’re an Apple fan, you don’t just buy an iPhone. You join the hordes of other iPhone users around the world, signifying your membership in the cult of Apple. When you stack up its features and its build quality, it isn’t necessarily the “best” in the smartphone category. The other people using it—the sense that they constitute a cohort that’s in the know—is the real draw.

Here’s a useful checklist list of old basics and new basics. Some of the shifts are subtle, others more dramatic. All are vital for business to understand and internalize, not only as marketing and communications principles but as drivers of value creation throughout your business. As you read the list, ask yourself: How can my business deliver on the new brand basics?

The New Brand Management

In the Conscience Economy, brand management is the vital wellspring of value creation because it is the manifestation of belief converted into action. But everyone—not just customer-facing staff—is responsible for its delivery. When such a core prerogative is relegated to a single functional department, its effectiveness is diminished. Start by acknowledging and communicating that brand management is part of everyone’s job.

If this sounds like breezy rhetoric, consider these questions: How can the team responsible for strategic acquisitions scan the marketplace for appropriate prospects if they haven’t internalized the ultimate ambition of the brand? How can engineers create new solutions if they don’t have a personal sense of where the business is going, and why it’s going there? How does HR establish coherent hiring standards that ensure not only the attraction of talent, but also cultural fit, if it isn’t directly engaged in the brand? Indeed, if your brand is not meaningful to everyone, as well as applicable to each employee’s daily work and decision making, then you’ve got an alignment problem. Fortunately, in my experience, the vast majority of people absolutely love getting involved in the creation, augmentation, evolution, and renewal of the brands for which they work. It can be the most exciting and meaningful part of their work. I’ve even gotten to know software engineers who became their companies’ most outspoken advocates.

This is not to say you should disband or laterally distribute your brand team, though it’s smart to assign a brand steward—a senior leader—in every function. That includes supply chain and logistics, legal, finance, facilities, HR, and more. Most crucial is to elevate the brand stewardship mandate. Reporting relationships are one way to do this. Consider making design, product innovation, communications, sales, and marketing all directly accountable to brand leadership; after all, these are the functions most tasked with value creation and delivery, communication, insight and foresight, creativity, and interaction with customers.

But before you shuffle your org chart, start by clarifying strategic roles and objectives. Key responsibilities need to be assigned:

- Leading and stewarding the process of creating a meaningful and thriving brand

- Aligning corporate behavior, operations, strategy, and decision making around brand

- Translating brand into new products, effective communication, and frontline sales strategy

- Maintaining consistent and recognizable brand standards that properly signify all that the business stands for in the broader marketplace

However you choose to organize it, the processes I describe below must involve participation across multiple functions, job roles, and layers in the business. It’s okay to look outside the company for help facilitating and distilling the meaning you create, but the content and meaning you generate must come from within. The process is as persuasive and aligning as the outcome.

1. Connect Your Values with Your Strategy

Ah, core values. So much good intent, and so many business books extolling the business value of core values. Does the following scenario sound familiar? A company workshops a set of core values, feels great about them, attributes them in some way to Our Great Founder from years past, and posts them somewhere on the corporate website. Sometimes they’re carved in sandstone at corporate HQ. They pop up in speeches from time to time. And other than that, values can sadly simply be a check in the box. “Yup, mission and values, we did those a few years ago at the offsite.” As for the values themselves, they’re always lofty and hard to argue with, and they can be pretty similar from company to company. “Respect” is a common one. “Integrity” is another. Even banks—currently the least trusted of business sectors when it comes to integrity—use this lofty language in their online “mission statements.”

The problem is that it’s all too rare that a business connects its values with its brand, let alone its strategy. But your brand is your values and your strategy. It is everything that you are. And it’s actually possible—thrilling, even—to make the link.

In the Conscience Economy, it’s vital to make this link because business operates in a culture in which values drive everything. I won’t be the first to say it: your values need to inform everything you do, not just sit on the intranet. The chief creative officer of an agency where I once worked even had the company’s values tattooed on his arm so he’d never forget them. I’m not one to argue with passion, and his was considerable.

Fifteen years ago, while I was working at an innovation consultancy in San Francisco, one of our clients, UPS, asked us if we could help them build a strategic framework that they could use to connect their legacy and their core values with their future vision and strategy.

My colleague Erika Gregory and I invented a framework and process to address the challenge, and I’ve been using it ever since, with organizations across a range of sectors, from telecom networking and consumer electronics to professional services and even public sector community groups. We call it the Brand Charter.

The Brand Charter is particularly effective as a sorting and prioritizing tool because it helps groups organize different ideas and ingredients of the company’s beliefs, goals, and plans.

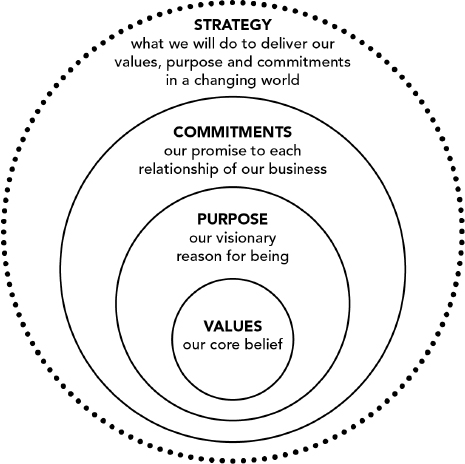

The charter is based on the principle of layering. Imagine a sphere, like the earth, with a deep gravitational pull toward its core, and dynamic life and interaction at its surface. This sphere—which is the totality of your brand—is composed of a series of layers of meaning, almost like a Russian nesting doll, with each layer encircling and protecting the layers within it.

At the core of a brand identity are an organization’s values and beliefs. Imagine those values and beliefs inhabiting a sphere at the core of a larger entity. These are things that will never change. The business model, the product line, the headquarters, the board—these might all go through multiple alterations. But those truths that are, within your business, sacrosanct and held to be self-evident, to quote the U.S. Declaration of Independence, these must never change. This is where conscientious brand building begins.

The next layer out, the sphere in which your core values are nested, is the organization’s purpose. It’s your reason for being, beyond just making money. It’s often best summed up in a single sentence, but again, the most important thing is not the perfect sentence, it’s the clarity of the idea. This is the place to be wildly ambitious and visionary, to lay out a proclamation of intent that’s groundbreaking, life improving, planet healing. There is no reason to hold back or aim for some kind of short-term realism. Spread happiness to all corners of the earth. Connect billions everywhere to a free education. Eliminate late diagnoses of disease. Banish pain and suffering. Increase human lifespans. Give every newborn baby an equal shot at life.

The next layer out from purpose is the organization’s commitments to each of those categories of people with whom it interacts. Its commitment to employees, suppliers, customers, citizens, partners, and more. This is often a series of up to nine different statements—it could indeed comprise more, but it’s best to limit the types of relationships to a manageable number.

And the final layer on the “outside” of this sphere we are creating is strategy—what the organization will actually do to manifest all the layers within, how you will deliver on your commitments. Strategy is the market-facing, public-facing layer of the overall brand charter. It is the one component of the framework that does change, as the external operating environment—disruptive technologies, emergent behaviors, customer demands, and other external factors—changes. Strategy articulates how you will mitigate risk and seize opportunity. And strategy is informed from two directions—from both outside the enterprise and simultaneously from within. In other words, although strategy is the organization’s response to market conditions, it is simultaneously supported by and even fueled by all that is encircled within the framework—it directly expresses the commitments to each business relationship, it delivers on the organizational purpose, and it is the means by which the organization’s core values are delivered and made real in the world.

But the world changes, constantly. The continual flux in which business needs to operate requires that strategy be revisited on a regular basis and summed up within this structure.

From years of experience deploying different frameworks in a range of boardrooms, I’ve concluded that this particular structure is, above all else, highly effective as a “sorting” mechanism that brings clarity and cohesion to a diverse set of agendas and priorities. If, for example, a team feels that “sustainability” is something important to the organization, we can then discuss: Is sustainability a core value, is it the purpose of the organization, is it actually a commitment to some key stakeholders, or is it a strategy to address an urgent need? I bring up sustainability intentionally, as it often emerges in these conversations, but it never “lands” in the same place within this framework.

I caution you to avoid the trap of wordsmithing. It can take weeks, months, to agree on the particulars of language, and even after years of working internationally, I can still be caught off guard by how one word can mean such different things to different people. For example, I’ve worked with a leadership team who couldn’t agree on the meaning of the word “progress.” To me, the word is irrefutably positive, referring to significant steps forward for humanity. But there were a few executives who saw the word in a negative light, who believed it suggested a kind of plodding incrementalism. My point is, important truths are always ideas, not terms, and while it’s helpful as a memory aid to sum these truths up with single words, it always takes more than one word to get the richness, depth, and distinctiveness of an idea across.

2. Make Brand a Story

Frameworks are great for helping groups discuss, sort, and organize ideas. They’re particularly excellent for demonstrating relational connections. But let’s admit it: no framework ever got your pulse racing. Frameworks don’t change hearts and minds—or behaviors. Stories do.

Here’s a simple exercise to get your team familiar with the concept. Ask each of them to describe Santa Claus in their own words. I (and you) already know what you’ll hear.

Every story will be told differently. Different words, different story structure. Each person’s story will be unique and personal, but everyone will describe the same persona, the same intention, the same rituals, the same identity signifiers. No one will struggle to remember the basic narrative. No mnemonic device or framework will be required. You’ll hear just a simple story, usually peppered with fondly remembered anecdotes from real life.

Next, ask if this “person” they are describing is real. Again, different stories, same meaning: “He’s a spirit of generosity, we’re all a little bit Santa at Christmas.” “He’s magical when kids need magic in their lives, and we want them to believe in him as long as possible.” “He’s kind of a ritual and we all play along because it brings joy and happiness and fun into our home.” “Of course he’s real. He’s in all of us.”

Santa is exactly like a brand. Because a brand is a recognizable identity, a belief system, a personality, and most importantly, today, a set of recognizable behaviors. We know he lives at the North Pole, that he has a team of elves making toys, and that he knows whether children have been bad or good. We know he’s chubby, has a big white beard, and wears a red suit trimmed in white fur. (That’s the Coca-Cola contribution. He looks like a big can of Coke.) We know how he sounds (ho ho ho) and we know that he comes down our chimney to put presents under the tree and into our stockings. We know that he’s omniscient but kind. And we know that he’s really a spirit or an idea that we try to embody for the children in our lives each Christmas. Even non-Christians know of Santa Claus. We see his image everywhere.

And a great brand is inspiring, just as Santa is. Meanwhile, religious associations aside, Santa (who has become a true pagan in his old age anyway) is an object lesson in what I call story management. He evolved organically, and yet the word and image have spread so consistently that people from various backgrounds and points of view can describe him accurately. Not only what he looks like and what he does, but his spirit, too.

It’s not important whether everyone in your business can recite your brand charter. What matters is that they can tell, in their own words, a “Santa Claus Story” about your company and brand. The point is to get outside of the traditional technique of creating a brand framework with specific words. The ultimate objective in conscientious brand management is for everyone in the organization to be able to tell the story of what the company is about—what it stands for, where it’s going, and most importantly, why—in their own words. It’s immediately evident whether people are telling the same story.

In other words, if everyone can share a personalized story of your business and what it means with the same consistency that we all can describe Santa Claus, then bravo, you’ve got a foundation for contemporary brand management in place.

How do you get there? You might already be closer than you think. Start by asking your people to tell, in two minutes, why they work for the business and what they believe the brand stands for. Suggest that they include their thoughts about how the brand is impacting the world. Note how consistently, or inconsistently, they tell their stories. Are their words personal? Do they include an anecdote? Are they reciting language from a training session? Just listen, and notice what you hear. It’s likely that you’ll be amazed at the consistency. But here’s a hedge: if the responses are profoundly misaligned (in my experience, they never have been), then your job is to listen at least for recognizable patterns, for themes that appear throughout the stories. The goal here is not to assess whether people are telling the same story in the same way, nor is it to convince them to do so. You’re looking for commonality that you can use to link points of view.

Next, model the act of storytelling yourself. Because the most powerful thing you can do as a leader is tell the story as you feel it and understand it. Doing this gives permission for others to personalize the way they talk about—and put to work—the values, purpose, commitments, and strategy of the company.

In the rare instance where people are unable to describe their own relationship to the company and its purpose in any kind of linked or consistent way, you will need to reinforce the importance of brand, and then demonstrate (from leadership as well as from customers) a few examples of consistent meaning shared in diverse ways. Divergent stories will quickly coalesce, because it is natural for people, and especially employees, to want to belong to something. If people don’t have a story about your brand within them, they will want one, and will be open to receiving and personalizing it.

For stories to spread, they have to be told, reinforced, discussed, and at times, ritualized. A great brand gets energy and potency from being at the heart of everyday conversations across the company. The more transparently you include your brand story as a driver of your leadership decisions, the more your people will put your story to work. In time, telling the story, and putting its meaning to work in everyday business decisions, becomes habitual.

3. Establish “Consistency Guidelines”

To state the obvious, brand value does not rise or fall based upon colors, typefaces, or photographic style guidelines. But it can rise and fall based upon consistency. So traditional brand guidelines (typically packaged in a “brand book”) really matter, and they need rigorous enforcement and advocacy from the top down and the bottom up. Consistency is vital.

Without consistency, you’re unrecognizable. Imagine if every time you saw your partner, he (or she) had undergone plastic surgery and had a different face. Imagine if he had a different voice too. Would you treat him the same way you did yesterday? Would you even engage with him? You couldn’t do it. Because you need to recognize the person with whom you’re in a relationship of trust and value exchange.

Okay, that’s an extreme example. But I hope it sticks in your mind, because multisensory identity guidelines are crucial. Calling them brand guidelines relegates them to a communications design function. Start calling them consistency guidelines.

Multisensory design consistency is as professionalized as financial accounting, and every business should take it just as seriously. Arguably, design consistency was as much a driver of Apple’s meteoric resurrection as the experiential innovation that fueled Apple’s portfolio. Suffice it to say, consistent and coherent logo use, colors, typeface, photographic and illustration style, sound components, real-world materials, and architectural and design principles are all as important as they’ve ever been. But here’s what’s new: a playful spirit and a willingness to let consumers manipulate and experiment with your identity are also vital components for brand expression. Showing your willingness to break your own rules from time to time keeps your identity vibrant, surprising, and human. Witness Google’s continual manipulation of its brand mark, a powerful way of stating the company’s point of view on current events.

Your brand is not only your identity but the voice with which you speak. Tone is crucial. With the premium they place on breaking down hierarchies and peer-to-peer connection, denizens of the Conscience Economy expect that brands speak as peers too, not condescendingly or patronizingly. The invitation to do good must be more like a seduction. Political correctness is the enemy of the Conscience Economy. Too often, consumers associate “responsible” with uncomfortable.

For example, a London advertising agency I know was recently hired to reposition and create a campaign for recycled toilet paper. I know what you’re thinking: scratchy. As Gail, the agency’s CEO, put it to me over a conversation in an editing suite, “No amount of sustainability is worth a scratchy bathroom experience. But repositioned as ‘ethical luxury,’ it offers a more compelling proposition. Because people actually do want to do something good. They just don’t want to pay more for it, or suffer for it.”

Gail’s observation is backed up by empirical evidence that may seem at odds with the motivations driving the Conscience Economy. Research shows that, although people increasingly care about social and environmental issues, most are unwilling to make sacrifices in order to support them, at least in their purchasing habits. I jump on Skype with Giana Eckhardt, one of the authors of The Myth of the Ethical Consumer, to get a better understanding of this paradox. And she puts it to me straight: when it comes to the mainstream, “when they’re spending money, people still care about value and convenience.”

Giana explains that the marketplace has unintentionally trained us to assume that products and services that are overtly marketed to us with a social or environmental purpose are more expensive, even when they’re not. So an overt social or environmental message can imply added expense and subconsciously put off customers even though they care about the topical benefits being conveyed. The exception to the perception of added cost as compromise, Giana notes, are people (aka hipsters) with, as she puts it, “identity concerns,” who want to be seen as caring and conscientious. For them, making an overtly conscientious purchase—signified by a desirable brand—indicates their social status, and they’re more than willing to pay for it. And when early adopters adopt a brand, it gains that ineffable cool factor, which can ultimately spread to the mainstream. Hence, I realize, the win-win of ethically luxurious toilet paper that feels as good on the conscience as it does, um, elsewhere.

Dismantling the notion that “good” means compromise is key to the Conscience Economy. Good can feel great, be naughty, wink-wink at you, or offer an experience that even feels indulgent. Indeed, the smartest brands in the Conscience Economy will be those with a voice and personality that is authentic, friendly, human, witty, and even darkly ironic. No one likes self-righteousness.

Staying on Top

A healthy brand is like a vibrant beating heart. In tough times, in many categories, particularly fast moving consumer goods, people will forgo their ideal brand to save money. The less cash people have the more price is going to motivate them. However, your competition will be playing the pricing game too. That downward pricing spiral can be deadly. Brands with enough equity can weather these storms of economic uncertainty.

If you’re currently enjoying your position at the top of the brand value charts, I have a special message for you. I worked with one of the world’s most valuable brands for several years. When sales were good, the brand was strong. Very little attention was paid to keeping it that way; indeed, the company ceased to manage the brand as an asset. It didn’t even have a CMO. And when sales began to decline, the brand declined, fatally. This is because the organization stopped internalizing future trends and believing it should change. It took its brand strength for granted in the good times, and neglected to future-proof it against unforeseen disruption. This is one of the most dangerous slippery slopes a successful company can face. When things are good, brand metrics appear strong, and the tendency is to maintain current procedures, to vigorously defend a status quo that’s driving seemingly endless profit, and to neglect the management of brand meaning as a core asset.

But if the brand has not been future-proofed for change, and the relationships with all those who are engaged in the brand itself are not open channels for dialogue, there may well be unseen vulnerability. “Only the paranoid survive,” goes the famous Andy Grove quote. Never take your brand health for granted. Treat it as your most vital asset, and nurture it appropriately.

With a healthy, vibrant, meaningful brand as your North Star, your compass, your guiding force for ongoing adaptation to the changing world around you, you future-proof yourself against the inevitable disruptions that buffet every business.

In the Conscience Economy the most robust meaning you can create—and the most powerful brand position you can secure in the hearts and minds of not only your customers but all the people your business touches—is that of a brand that stands for something authentically, socially, environmentally, humanly good. But the brand must also deliver on that promise. It’s no longer about compartmentalizing values, purpose, promise, and strategy. It’s about integrating them. It’s no longer about departmentalizing corporate social responsibility. It’s about embedding positive impact in everything you do.