Sameer Bhatia was always good with numbers—and he approached them, as he did everything in his life, from a unique perspective. When the Stanford grad was in his twenties, he came up with an innovative algorithm that formed the foundation of his popular consumer barter marketplace, MonkeyBin. By age thirty-one, the Silicon Valley entrepreneur was running a hot mobile gaming company and was newly married. His friends, who called him Samba, adored his energy, optimism, and passion for pranks. Sameer had an ability to bring out the best in people. With an unrestrained zest for life, he had everything going for him.

Then, on a routine business trip to Mumbai, Sameer, who worked out regularly and always kept himself in peak condition, started to feel under the weather. He lost his appetite and had trouble breathing. He wanted to blame the nausea, fatigue, and racing heartbeat on the humid hundred-degree monsoon weather, but deep inside, he knew something else was wrong.

Sameer visited a doctor at one of Mumbai's leading hospitals, where his blood tests showed that his white blood cell count was wildly out of whack, and there were "blasts" in his cells. His doctor instructed him to leave the country as soon as possible to seek medical treatment closer to home. Immediately upon entering the United States—before he could even make it back to his hometown of Seattle—Sameer was admitted to the Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital in New Jersey. He was diagnosed with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), a cancer that starts in the bone marrow and is characterized by the rapid growth of abnormal white blood cells that interfere with the production of normal blood cells. AML is the most common acute leukemia affecting adults; it's also very aggressive.

Sameer was facing the toughest challenge of his life. Half of all new cases of leukemia result in death (both in 2008 and today). But Sameer was determined to beat the odds and get better. After Sameer underwent a few months of chemotherapy and other pharmacological treatment, doctors told him that his only remaining treatment option would be a bone marrow transplant—a procedure that requires finding a donor with marrow having the same human leukocyte antigens as the recipient.

Because tissue types are inherited, about 25 to 30 percent of patients are able to find a perfect match with a sibling. The remaining 70 percent must turn to the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP), a national database with over eight million registered individuals. Patients requiring a transplant are most likely to match a donor of their own ethnicity. That wasn't a promising scenario for Sameer, however. He had a rare gene from his father's side of the family that proved extremely difficult to match. His brother, parents, and all of his cousins were tested, but no one proved to be a close match. Even more worrisome was that of the millions of registered donors in the NMDP, only 1.4 percent were South Asian. As a result, the odds of Sameer finding a perfect match were only one in twenty thousand. (A Caucasian person has a one-in-fifteen chance.) Worse, there were few other places to look. One would think that a match could easily be found in India, Sameer's family's country of origin. After all, India is the world's second-most populous country with nearly 1.2 billion people. But India did not have a comprehensive bone marrow registry. Not a single match surfaced anywhere.

People often ask what they can do to help in harrowing times. The answer is hard to find. Do you offer to drop off a meal? Lend an empathic ear? Such overtures are well intentioned, but rarely satiate the person who wants to help or the person who needs the help.

Sameer's circle of friends, a group of young and driven entrepreneurs and professionals, reacted to the news of Sameer's diagnosis with an unconventional approach. "We realized our choices were between doing something, anything, and doing something seismic," says Robert Chatwani, Sameer's best friend and business partner. Collectively, they decided they would attack Sameer's sickness as they would any business challenge. It came down to running the numbers. If they campaigned for Sameer and held bone marrow drives throughout the country, they could increase the number of South Asians in the registry. The only challenge was that to play the odds and find a match that would save his life, they had to register twenty thousand South Asians. The only problem: doctors told them that they had a matter of weeks to do so.

Sameer's friends and family needed to work fast, and they needed to scale. Their strategy: tap the power of the Internet and focus on the tight-knit South Asian community to get twenty thousand South Asians into the bone marrow registry, immediately. One of Robert's first steps was to write an email, detailing their challenge and ending with a clear call to action. In the message, he did not ask for help; he simply told people what was needed of them. Because this was the first outbound message broadcasting Sameer's situation, Robert spent hours crafting the email, ensuring that every word was perfect and that the email itself was personal, informative, and direct. Finally, he was ready to send it out to a few hundred people in Sameer's network of friends and professional colleagues.

Dear Friends,

Please take a moment to read this e-mail. My friend, Sameer Bhatia, has been diagnosed with Acute Myelogenous Leukemia (AML), which is a cancer of the blood. He is in urgent need of a bone marrow transplant. Sameer is a Silicon Valley entrepreneur, is 31 years old, and got married last year. His diagnosis was confirmed just weeks ago and caught us all by surprise given that he has always been in peak condition.

Sameer, a Stanford alum, is known to many for his efforts in launching the American India Foundation, Project DOSTI, TiE (Chicago), a microfinance fund, and other causes focused on helping others. Now he urgently needs our help in giving him a new lease on life. He is undergoing chemotherapy at present but needs a bone marrow transplant to sustain beyond the next few months.

Fortunately, you can help. Let's use the power of the Net to save a life.

Three Things You Can Do

Please get registered. Getting registered is quick and requires a simple cheek swab (2 minutes of your time) and filling out some forms (5 minutes of your time). Registering and even donating if you're ever selected is VERY simple. Please see the list of locations here:

http://www.helpvinay.org/dp/index.php?q=event.Spread the word. Please share this e-mail message with at least 10 people (particularly South Asians), and ask them to do the same. Please point your friends to the local drives and ask them to get registered. If you can, sponsor a drive at your company or in your community. Drives need to take place in the next 2–3 weeks to be of help to Sameer. Please use the power of your address book and the web to spread this message—today more than ever before, we can achieve broad scale and be part of a large online movement to save lives.

Learn more. To learn more, please visit

http://www.nickmyers.com/helpsameer. The site includes more details on how to organize your own drive, valuable information about AML, plus FAQs on registering. Please visithttp://www.helpvinay.org/dp/index.php?q=node/108for more information on the cities where more help is needed. Another past success story from our community is that of Pia Awal; please read about her successful fight against AML atwww.matchpia.org.

Thank you for getting registered to help Sameer and others win their fight against leukemia—and for helping others who may face blood cancers in the future.

Truly, Robert[21]

Robert sent the email to Sameer's closest friends and business colleagues—about four hundred to five hundred members of their "ecosystem," including fellow entrepreneurs, investors, South Asian relatives, and college friends. And that set of friends forwarded the email to their personal networks, and on the message spread virally from there. Within forty-eight hours, the email had reached 35,000 people and the Help Sameer campaign had begun.

Sameer's friends soon learned that yet another man in their ecosystem had recently been diagnosed with the same disease: Vinay Chakravarthy, a Boston-based twenty-eight-year-old physician. Sameer's friends immediately partnered with Team Vinay, an inspiring group of people who shared the same goal as Team Sameer. Together, they harnessed Web 2.0 social media platforms and services like Facebook, Google Apps, and YouTube to collectively campaign and hold bone marrow drives all over the country.

Their goal was clear, and their campaign was under way. Within weeks, in addition to the national drives, Team Sameer and Team Vinay coordinated bone marrow drives at over fifteen Bay Area companies, including Cisco, Google, Intel, Oracle, eBay, PayPal, Yahoo!, and Genentech. Volunteers on the East Coast started using the documents and collateral that the teams developed. After eleven weeks of focused efforts that included 480 bone marrow drives, 24,611 new people were registered. The teams recruited thirty-five hundred volunteers, achieved more than one million media impressions, and garnered 150,000 visitors to the websites. "This is the biggest campaign we've ever been involved with," said Asia Blume of the Asian American Donor Program. "Other patients might register maybe a thousand donors. We never imagined that this campaign would blow up to this extent." Nor did anyone imagine that this campaign would change the way future bone marrow drives are conducted.

Perhaps the most critical result associated with the campaign, however, was the discovery of two matches: one for Vinay, one for Sameer. In August 2007—only a few months after the kick-off of the campaign—Vinay found a close match. Two weeks later, Sameer was notified of the discovery of a perfect (10 of 10) match. Given the timing of when the donors entered the database, it's believed that both Vinay's and Sameer's matches were direct results of the campaigns. Furthermore, it was clear that Sameer and Vinay would not have found matches the traditional way. It takes four to six weeks for a new registrant from a drive to show up in the national database, so they would have needed many more than twenty thousand new registrants to have a statistical chance at a match in such a short time. As Sameer wrote on his blog, "Finding a match through this process in the time required would be nearly impossible. Yet many hundreds of hands and hearts around the nation united behind this cause... . You all have given me a new lease on life and for that I don't have adequate words to thank you."[22]

Perhaps even more incredible, however, was that the impact of Team Sameer and Team Vinay did not stop with just Sameer and Vinay. Ultimately, they educated a population about the value of becoming registered donors while also changing the way registries work. Above all, they came up with a blueprint for saving lives—one that could be replicated.

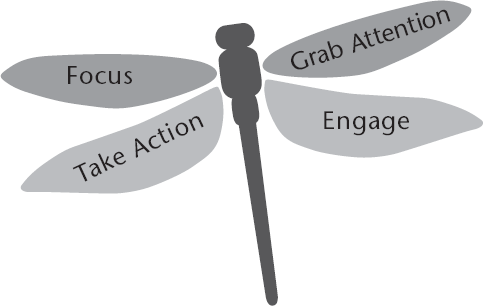

How did Team Sameer achieve, in the words of Robert Chatwani, "something seismic"? They didn't set out to help design a system that could be easily, efficiently, and effectively repeated. They just wanted to save their friend's life. But in exceeding the goal by registering 24,611 South Asians into the NMDP registry in eleven weeks, Robert and the team uncovered a process that can be applied to achieve any goal. The effectiveness of the effort can be traced to four steps or principles—Focus, Grab Attention, Engage, and Take Action. To keep it simple, think of the mnemonic Focus + GET.

A dragonfly travels with speed and directionality only when all four of its wings are moving in harmony. Metaphorically, then, the central body of the dragonfly should embody the heart and soul of the concept or person you are aiming to help.

To understand how Team Sameer was so effective, consider each of these principles: Focus, Grab Attention, Engage, and Take Action. First, the team focused sharply by concentrating exclusively on a single goal. It wasn't hard. The doctors were clear. The chances of finding a bone marrow match were one in twenty thousand. The team needed to get at least twenty thousand South Asians in the bone marrow registry within weeks. But they didn't get lost in the size of the challenge. They didn't try to sign up every single South Asian in the Bay Area. Instead they focused on those who were well connected to others (for network effects), those who were parents (who could envision their children battling a similar challenge), and those who could relate to Sameer and his story. Those types of individuals were easy to identify, and the scope of the challenge quickly came into focus.

Second, Team Sameer grabbed attention by empathizing with their donor audience, relying on photos, making the messages compelling and personal. They also mixed media, employing social media (blogs, video, viral email, Facebook, widgets, pledge lists) as well as traditional media (public relations, television, magazine, telemarketing, posters, and newspapers) and leveraged relationships with celebrities and luminaries. (Then-senator Barack Obama wrote a note in support of the cause, simply because a friend of Vinay's asked him.)

Third, Team Sameer engaged deeply with others by making Sameer knowable, telling his story authentically and vividly through video and blog entries, so his story became personally meaningful—even to strangers. The team used targeted messaging to help audiences see themselves in Sameer. Some messages focused on Sameer's South Asian background; others highlighted his youth, newlywed status, or his professional pursuits as a technology entrepreneur.

Team Sameer and Vinay built out a website that acted as a repository for stories, updates, information, and feedback (http://www.helpsameer.org/strategy/). Here volunteers could download materials from a menu including Fliers, Literature, or How to Create a Video. There was even a downloadable how-to guide called "Hosting a Bone Marrow Drive at Work," a Word document with simple instructions and sample emails that could be customized by others as needed. The team provided links to downloadable PDFs of the family's appeal, a Tell-a-Friend link that led to Vinay's website, email templates that people could send to their friends, footer templates that people could add to their email signatures, banners to put on blogs or websites, and videos that people could add to their own Facebook pages. Team Vinay worked with Team Sameer to leverage each of these assets by linking and feeding communication across teams, essentially creating one big campaign.

Fourth, Team Sameer enabled others to take action by creating a clear and easy-to-execute "call to action" in all communication materials. For example, the call to action was abundantly clear on the website. An online calendar listed donor drives while the text on the welcome page nudged, "Hey visitor, have you already registered?" The site also hosted content that walked people through each step of holding a bone marrow drive, or even what individuals could expect when they attended a drive as a donor. Team Sameer further fueled its call by tracking metrics and collective impact and then feeding those results back to its members, a community of friends, family members, and strangers.

Although certain tasks needed to be coordinated "top down," many did not. The leaders broke off anything that didn't require top-down leadership and empowered (and encouraged) individuals to take action on their own. Communications across the team to share best practices were also important, and using tools such as Google Groups to facilitate those communications proved critical—allowing both groups to move ahead with agility and speed.

"We often tried to think of the traditional way to do something and considered what would happen if we did the exact opposite—reversing the rules," says Robert. "We weren't wedded to a right way of moving ahead. We just moved ahead. And we empowered others to move ahead just as quickly." As Team Sameer member Sundeep Ahuja explains, "We believed in 'act first, then think.'" When one of their ideas was successful, they would focus on putting more energy and time into that winning idea. For example, once they saw that corporate workplace drives were effective, they continued with that and didn't think of much else. They put some banners on their site and soon noticed that they weren't yielding registrations, so they didn't invest further in that effort. "Our motto was try, abandon, move on, try, abandon, move on ..."

Although each wing was important individually, it was the integrated impact of the four wings working in concert that led to Team Sameer's disproportionate results. None of these methods would have been effective without the prior, contributing impact of the other steps driving the audience toward becoming active participants.

Sameer's transplant was completed in fall 2007. One day before getting his transplant, Sameer's blog reflected optimism and his usual sense of humor (plus his love of emoticons): "I consider myself to be extremely lucky. I've had near normal energy levels and no pain or discomfort... . Until then, we are enjoying

Sameer also posted pictures and videos of his bone marrow transplant on YouTube. The videos consisted of small bits of different parts of the procedure, with the first clip showing him anxiously looking at the bag of bone marrow and touching it while looking for his name. Sameer's father tells him not to move it around too much, to which Sameer laughs and responds, "Don't move it around too much? These cells were just shipped across the country and made it through baggage claim!" Another part shows Sameer holding the tube and watching as the bone marrow cells find their way into his body.

Three months after the transplant, just a few days before Christmas 2007, Sameer relapsed. In typical Sameer fashion, he was back to blogging by December 26. "I don't believe in setbacks," he wrote. "We must grow from this experience, whatever pains—physical and emotional—it brings us. What else, after all, is the process of life if not growth?"

After several additional setbacks and a valiant fight, Sameer passed away in March 2008. Friends and family mourned with a memorial service, delivered via a live webcast, which was attended by more than five hundred people throughout the world, some of whom knew Sameer and some of whom did not—all of whom were touched by his story.

The service was recorded and posted on Google Video. Several thousand people viewed the memorial in the first seven weeks after his passing. Sameer's memorial photo slideshow, which joyfully depicts his commitment to his culture, family, and friends (and his penchant for costumes, including plaid skirts) was viewed over 6,000 times as well. "We knew that there were thousands of people around the world that couldn't be with us, so we put everything online," says Robert. "The idea that we could use technology to break down barriers and boundaries was very powerful. It was our way of connecting Sameer's friends and family from around the world to his memorial, which was a celebration of his life."

The week that Sameer died, Vinay, who had received his transplant and made it to the hundred-day mark (what patients aim for so as to be in the clear), was admitted to the ICU. Vinay fought for several months, undergoing chemotherapy and alternative drug treatments. Despite his courage, and the global effort to save his life, Vinay passed away in June 2008.

That's not the end of their stories, though. Their legacy, and their movement, continued to grow worldwide.

Through an integrated strategy that leveraged technology, passion, and persistence, as well as an understanding that they couldn't succeed without the help of others, Team Sameer and Team Vinay together reached their goals of registering more than twenty thousand donors and finding a match for both men. Beyond the teams' success in rapidly registering mass numbers of donors, they would ultimately inspire many others and save many other lives. From the base of seventy-five hundred people who registered in the Bay Area, where Sameer lived, eighty additional matches for other leukemia patients were discovered within a year. In 2008 alone, through the efforts of the two teams, 266 other individuals surfaced as matches and donated bone marrow.

Further, the campaign nearly doubled the number of South Asians registered with the NMDP, and retention rates for South Asians have improved to 50 percent, according to Asia Blume of the Asian American Donor Program. Moreover, the campaigns inspired others to change their perception about donating, and that alone has changed lives. Pharmacy student Rina Mehta heard about Team Sameer and Team Vinay from a friend who sent her an invitation through Facebook along with information about a drive in Fremont, California. "It was so easy to register that I decided to do it, and I told everyone I knew to do the same, including my parents," says Rina. Within six months, she received a phone call from the donor program requesting that she come in for more testing, as she was a potential match for another patient. Rina became a peripheral blood stem cell donor to an eighteen-year-old male leukemia patient. "I decided to donate because my fear and any inconvenience it might cause me paled in comparison to what he was going through."

Perhaps the greatest legacy, however, spans far beyond leukemia and marrow donation. The story of Sameer and Vinay is one with a remarkable impact: it shows how the technologies we have at our fingertips can enable us to share stories, mobilize support, and take action to change lives. The two teams started a revolution that can be passed on to others who face similar situations. "We want to give people everything that we did so they can just plug into it, use it, and add onto it," says Dayal Gaitonde, one of Sameer's closest friends and a key member of Team Sameer. "We're looking to open source everything that we did to help others in similar situations."[24]

Big revolutions start with simple ideas and ordinary people. "The notion that there are constraints becomes irrelevant. The biggest asset you have is the ability to think clearly, then take a very big idea and run with it," says Robert.

Now that you've seen the Dragonfly Effect in action, it's time to break it down and show you how to make it work for you. In the next chapter, we'll start with the first wing (skill): Focus.