As we look ahead to the next century, leaders will be those who empower others.

In many ways, Alex Scott was a regular kid. Her favorite food was French fries; her favorite color, blue. She hoped to be a fashion designer one day. But in other ways—perhaps most ways—Alex was different. Just before her first birthday, Alex was diagnosed with neuroblastoma, an aggressive form of childhood cancer. A tumor was removed from her back, and doctors told her parents, Liz and Jay, that if she beat the cancer she would likely not walk again. Two weeks later Alex moved her leg—one of the many early clues about her determination and capabilities.

When Alex was four, after receiving a stem cell transplant, she came up with a plan that would change how she and her family coped with cancer from then on. "When I get out of the hospital I want to have a lemonade stand," she said. Alex wanted to use the money she made to fight cancer and help other children.

Her parents admit now that they laughed. (Not a bad reaction ... we know that laughter in the midst of challenge is good.) Admittedly, it was an unlikely proposition. Although one in every 330 American children contracts cancer before age twenty, childhood cancer research is consistently underfunded.[132] Alex was advised that it could be challenging to raise money fifty cents at a time. "I don't care; I'll do it anyway," she replied.

Alex set up a table in her front yard, and like thousands of other junior entrepreneurs around the country, started selling paper cups of lemonade to neighbors and passersby. Her hand-printed sign advertised (along with the price of the lemonade) that all proceeds would go to childhood cancer research. The fifty-cent price was ignored as customers paid with bills ($1, $5, $10, and $20) and allowed her to keep the change as a donation. (Alex understood the importance of change management, and the change really added up—similar to Bank of America's Keep the Change program, which allows customers to round up their debit card purchases to the nearest dollar, and deposit the difference into their savings accounts. Of course, Alex did it first.)

True to her word, Alex raised more than $2,000 from her first lemonade stand. She reopened her stand for business each summer, and news of its existence and worthy cause spread far beyond her neighborhood, her town, and even her home state of Pennsylvania. She leveraged that momentum and got others to set up their own lemonade stands. Her approach was sticky in more ways than one. Before long, lemonade stand fundraisers took place in each of the fifty states, plus Canada and France. Alex and her family appeared on the Oprah Winfrey Show as well as the Today Show.

Not one to be easily daunted, Alex set a goal to raise $1 million for cancer research. By the time she reached $700,000, Volvo of North America stepped in and pledged to hold a fundraising event to assure that the $1 million goal would be reached.

Four years after setting up her first lemonade stand, Alex succumbed to cancer. She was eight. In her too-short life she raised $1 million for cancer research, built awareness of the seriousness of childhood cancer, and taught a generation of children (and their parents) about the importance of abstract ideals like community and charity. She also demonstrated that making a difference can be fun.

To carry on Alex's legacy, her parents established a nonprofit in her name, Alex's Lemonade Stand Foundation (ALSF). Since its founding, the 501(c)3 charity has inspired more than ten thousand volunteers to set up more than fifteen thousand stands. As of January 2010 it's raised an excess of $27 million and donated to more than one hundred research projects at nearly fifty institutions in the United States. Alex assembled a band of cancer-fighting evangelists (family, friends, neighbors, citizens, corporations) that was far more powerful than anyone, even those closest to her, ever thought possible. ALSF called people to action, and grew exponentially, with the help of social media, which allowed the organization to garner a strong and faithful fan base—30,000 Twitter followers and 33,000 Facebook fans. People all over the world took Alex's idea and transformed it into a movement.[133]

The success of Alex's Lemonade Stand Foundation wasn't as much about raising money as it was inspiring people to take action. By helping children around the country set up their own lemonade stands to fight childhood cancer, Alex mobilized a population of young ambassadors whose involvement and heightened awareness made a much more significant impact.

The organization embraced all four wings of the dragonfly: it focused on the goal of honoring Alex's wish to raise money to fight childhood cancer; it grabbed attention by tapping into a deep-rooted American tradition, the lemonade stand, owning a color (yellow), and creating sticky subbrands (including LemonRun and "Freshly Squeezed Friday News"); it engaged people's emotions by telling Alex's compelling story. And finally, it excelled at the fourth wing of the Dragonfly Effect, Take Action, the wing critical to closing the loop on previous efforts by enabling others to easily start their own lemonade stands and become part of the solution.

When you grab people's attention, they sit up and listen. When you engage people, you connect with them and inspire them. However, too many efforts just stop there, leaving people with good intentions that may never be acted on. What was critical in the case of Alex's Lemonade Stand Foundation was how it enabled action by providing its audience with the tools to get them to do something. Take Action is about requiring individuals to exert themselves and to make the transition beyond being interested by what you have to say to actually doing something about it. After all, in a world where a blanket with sleeves constitutes a hot-ticket item, it's hard to get people off the couch.

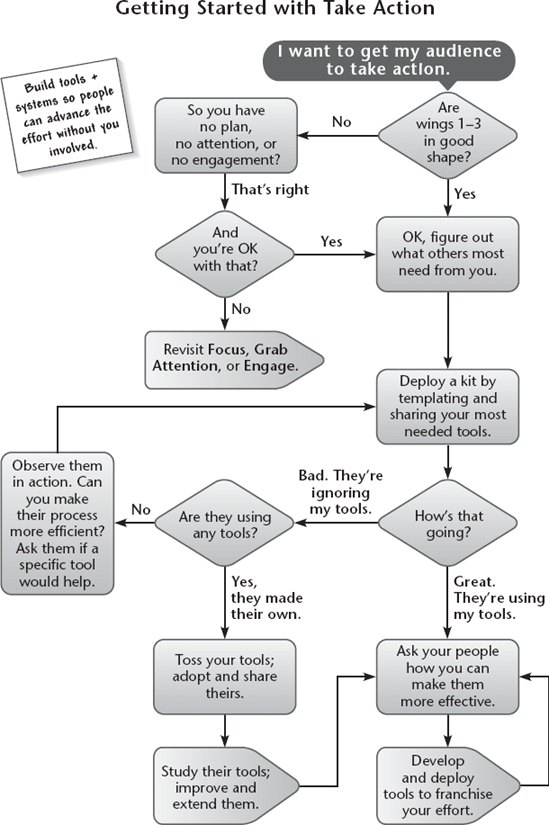

The final wing is pivotal, but far from simple. You need to know what to ask for and how to ask for it. Second, you must listen to how the audience responds so that you can continually integrate their reactions and feedback, honing and refining your message and sometimes the offering itself. But before we dive into these two skills, we'll define a call to action.

"Call in the next five minutes to get this special price." "Quantities are limited, so act now!" You're likely no stranger to the call to action—the message at the end of a commercial when someone oozing with urgency tells you what to do.

The call to action at the end of sales and marketing materials has traditionally been embraced by marketers as a way to convert mere prospects into customers. They provide audiences with participative next steps that move them closer and closer to making a purchase. Many calls to action fail (and not just the cheesy, clichéd ones) because they don't offer anything more compelling than a "P.S." urging the recipient to call a certain phone number or click on a URL. That's not a call to action; that's a feeble whimper.

Unfortunately, nonprofit organizations are making these mistakes too. Worse, many are even less sophisticated—failing to provide even the minimal calls to action that their for-profit counterparts do. Nonprofits routinely try to disseminate information about their causes without providing specific instructions on how the interested parties should act. (Many of us incorrectly believe that simply providing information will be more effective than asking outright.[134]) Technology companies tend to fall into this trap too, expecting that clear, objective disclosure of features and functions will speak for themselves, that the choice will be self-evident. It usually isn't. Further, organizations often fail to use social networking to create a sense of community with their educational campaigns. That's a missed opportunity. People like to consult with others before devoting money or time to a cause; they want to ensure that their money and time will be well spent. (This phenomenon explains the popularity of the ratings systems of Amazon.com, where users "grade" books and other retail products, or Yelp, which does the same for local businesses and services.)

When organizations do combine the power of the call to action with innovative social media tools, they can achieve extraordinary results. Take the campaign Take a Bite Out of IHOP's Animal Cruelty, which the Humane Society of the United States launched to try to get the restaurant chain to use cage-free eggs. The Humane Society used Facebook's status-tagging features to ask their 170,000-plus Facebook fans to tag IHOP when they changed their status or posted a new message to express their outrage about what it perceived as IHOP's inhumane practices.[135] This had an immediate and powerful effect. As the campaign went viral, more and more people tagged status updates. The posts showed up on IHOP's fan page, where it had 57,000 fans (which translates into a lot of eggs). Within six weeks, IHOP was forced to address the issue,[136] and its executives have since agreed to test the use of cage-free eggs and promised to switch millions of eggs to cage-free if the testing proved successful.

You get that you have to make an ask—that you must literally compel the audience into action. But how? There are many different types of asks, but only one constant: what you are asking of people must be highly focused, absolutely specific, and oriented to action, so as to avoid overwhelming your audience. Behavior change occurs when the behavior is easy to do.[137] Research suggests that when it comes to encouraging others to help, small asks often lead to better results. Offering diverse opportunities to contribute to your cause over time and regularly communicating new ways to get involved can lead to donor satisfaction and raise more money.[138] As we discussed in Wing 1, specific manageable goals help people enjoy a task more.[139] You can empower others by keeping your request focused.

We have observed three effects at work when it comes to using social media to drive others to take action for a cause. First, setting up a social Web presence to solicit donations is so easy that it has led to a proliferation of money asks. Second, social media users expect transparency, so we are seeing much more data on fundraising progress than we have ever been privy to before. Third, as we see in the best examples, social media are far more than fundraising tools. Social networks are particularly effective at increasing motivation,[140] and they enable us to quickly create a critical mass of supporters who then serve as agents for action. Although effective use of social media in the nonprofit sector varies dramatically across organizations, thinking of the benefits beyond fundraising is a smart way to expand reach and impact, as the nonprofit social media expert Beth Kanter points out.[141] We couldn't agree more.

Nonprofits suffer as much as businesses from economic downturns. Donations at two-thirds of public charities declined in 2008, according to the Giving USA Foundation.[143] This represents the first decrease in donations in current dollars since 1987, and only the second year-over-year giving slump since the organization began publishing its annual reports fifty-two years ago. In a similar vein, the amount of time volunteers have donated to causes has been flat for several years, according to the Corporation for National and Community Service.[144] Given these trends, nonprofits are constantly searching for ways to increase both the number of donors and the amount of time or money that donors offer. They have three strategic issues to consider: what to ask for, how to ask for it, and when to ask for it. Correctly combining these factors can determine whether you meet, exceed, or fall short of your goal. The rest of this chapter will focus on how to design your ask to achieve the most effective results.

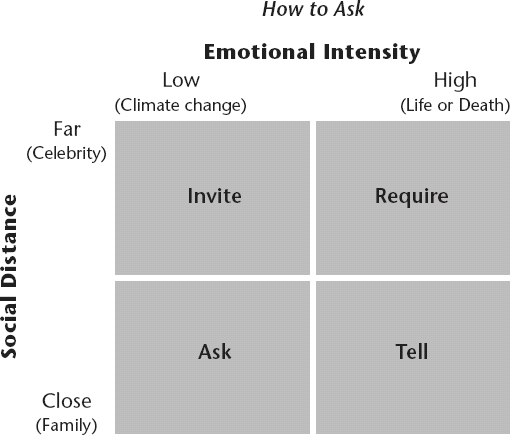

Research assessing why people volunteer time and contribute money to charitable causes found that the number one reason is that "they were asked by someone,"[145] which suggests that the way you ask matters. But it's not enough to simply ask for time, money, or both. You need to carefully calculate the what, how, when, and scope of your ask to yield maximum results. Whether you ask for or require participation should be based on two factors: your degree of separation from the potential donor and the emotional intensity of your ask. If you're socially close to a potential donor and the emotional intensity is high (your friend is battling an aggressive form of cancer), you are in a position to simply tell him or her to participate. These are your family members and close friends; they trust you and want to help you. If the emotional intensity is relatively low ("let's work together to stop climate change"), you should approach them with an ask, not a tell. (The reason: without the emotional component, it should be up to potential donors' discretion whether they care to be involved. Still, you ought to be able to count on a close friend or relative for at least a small contribution.)

When the social distance is great (between you and Brad Pitt, for example), and the emotional intensity high, you can require participation and hope that your potential supporter is as moved to act as you are. This works best in movements inspired by outrage—for example, those fighting against inhumane treatment of children or animals. If the cause is less emotionally intense, then a softer ask, such as an invitation, will be more effective.

Try using the framework above as a litmus test. For example, imagine you're running for Team in Training (the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society's charity sports training program) and are soliciting support from friends. The social distance is very close, but the emotional intensity is low, so it would be a straightforward ask. In contrast, if you are soliciting support from executives at your corporation (social distance is far), think in terms of an invitation. However, if your child has leukemia, you have a license to require. In that case, if you are soliciting your friends, it would be a tell. Remember, they are your support network, and you would do the same for them.

No person is too high on the social, economic, or political scale to approach for your cause. No matter how socially distant an individual is, it is worth asking him or her. Endorsements by public figures have been proven to raise the profile of charities and spread awareness.[146] Princess Diana, who supported almost a hundred charities, humanitarian organizations, and civic groups during her lifetime, most visibly with her efforts to ban land mines, helped raise an estimated $450 million each year.[147] Public figures' endorsement of nonprofit causes has been rising over the years. Don't be afraid to tell them you need them. So many people tiptoe nervously around celebrities, treating them as if they were not quite human, that anyone who treats them as peers is likely to stand out. Give it a shot—you have nothing to lose.

One thing to strategize constantly is how a first action will lead to a second action, and so on. If you've settled on a strategy of "micro participation," as Kiva has, how do you construct your ask so that a single action becomes the first rung of a ladder into a long-term relationship? You must specify what you want people to do right now, even as you anticipate and provide further opportunities for them to become even more involved.

Free trials of products or services can serve as a first rung. In a five-minute video on the social networking site Ignite (sponsored by O'Reilly Media), Alexis Bauer beautifully illustrated the ladder concept. Check out "How to Work a Crowd," in which Bauer explains how to plant conversational seeds in a room full of strangers. The first time you talk to a person you are a stranger, she explains. But after you've moved around the room and planted numerous other seeds, when you come back to that person, you are no longer a stranger but a familiar face—and the next time, you're greeted as friend, one trusted enough to introduce that person to other "friends" you've made during your rounds.[148]

We've already seen how political campaigns and nonprofits have effectively used the social Web to achieve what would have been impossible only a few years ago. When Areej Khan wanted to ignite a debate on the ban on women drivers in Saudi Arabia, she didn't seek monetary contributions; she simply asked individuals to write their opinions on stickers that could be uploaded and circulated on Flickr and offline as bumper stickers. Ultimately, her To Drive or Not to Drive effort started an important dialogue both online and offline. Help Sameer and Help Vinay encouraged thousands of people to join the bone marrow registry and never asked for any money. "Vinay felt that by accepting money, you were telling people that it was okay not to go and register," says Priti Radhakrishnan, who ran Help Vinay. "We were really focused on our goal, and money wouldn't have gotten us there."

Research has found that when you ask for time, your product or cause can become more alluring and better liked.[149] The time-ask effect shows that focusing your message on time (versus money) can affect your audience's willingness to contribute. We conducted experiments, both in the lab and in the field, which revealed that asking individuals to think about how much time they would like to donate to a charity actually increases the amount of money they ultimately contribute to the cause.[150] (See the preceding box for more details.)

There's important related research on happiness. Studies have found that younger people see happiness as an excited, high-arousal feeling, whereas older people perceive happiness as a peaceful, content feeling. This transition as people age may be caused by feelings of connectedness with other people.[152] The meaning of happiness varies across cultures (and religions) as well. People from individualistic cultures, such as European Americans (and Christians), are more likely to value excitement, whereas people from collectivist cultures, such as East Asians (and Buddhists), value calm.[153] Part of the success of Alex's Lemonade Stand Foundation can be attributed to its ability to draw in diverse cultures and age groups through its community-building activities. ALSF creates ongoing excitement and fosters a sense of connection that contributes to the project's sustainability. By focusing on asking for time versus money, the group successfully gains traction with different audiences and spurs them into action.

Asking for time activates an emotional mind-set that makes well-being and happiness more easily accessible—thus leading to donations.[154] When people are solicited for their time, they are more likely to think in terms of emotional meaning and fulfillment: "Will volunteering for this charity make me happy?" When tapped for money, they start thinking about the far more practical, boring, and sometimes painful matter of economic utility: "Will donating money make a dent in my wallet?" Thinking about money makes people become less helpful to others and makes them want to play and work alone.[155]

The Dragonfly Encyclopedia of Asks, following, explores the many different types of asks and how to employ them effectively.

The reality of today's world is that many people simply don't have a lot of time to give to a cause. You have to be sensitive to this, or you will have trouble attracting and retaining active participants. By demonstrating that you value their time and by making efficient use of their contributions—perhaps by precisely matching tasks to their particular interest or skill set—you can simultaneously boost their effectiveness while giving them a greater sense of accomplishment. This increases the likelihood that they will continue to participate.

Helping people achieve small goals leads them naturally to adopt more ambitious behaviors, often without a bigger intervention. For example, if the big goal is to convince people to be more environmentally friendly, ask them to do something small first. Suggest that they change a single light bulb in their home. Let them breathe for a moment, basking in their success, and then intervene again, expanding the effort by making the target behavior more difficult. Perhaps you might suggest that they replace all the inefficient light bulbs in their home.[160]

The Extraordinaries, which Ben Rigby was inspired to cofound after reading that nearly half of respondents to a poll cited lack of time as the main reason they didn't volunteer, demonstrates the value of the small, easy ask. The organization has captured a unique opportunity by providing people with a way to put downtime to good use. Rather than interrupt their supporters when they're trying to do something else and asking them to take an action then (what Seth Godin refers to as "interruption marketing"), the Extraordinaries allows people to choose a cause and an activity (for example, identifying elements in images for the Smithsonian) and volunteer at their convenience. People download the Extraordinaries iPhone application and forget about it until they have five or ten minutes on their hands to micro-volunteer.

This effort is all about empowering potential volunteers or donors and keeping them from feeling overtaxed or overwhelmed. Yahoo! excelled at this with its You In? campaign, launched over the 2009 holidays. You In? attempted to enlist its employees—famous for being young and hip—to engage in random acts of kindness and in doing so to create ripple effects. The campaign was easy to understand and even easier for individuals to envision themselves joining. Employees who performed acts of kindness were encouraged to post their stories on the Yahoo! For Good website, or their videos or pictures to a linked Yahoo! Flickr group. Typical acts of kindness included topping off a parking meter, paying a toll for the car behind, and shoveling snow. Yahoo! employees from eighteen countries participated, submitting over 300,000 status updates of random acts of kindness.

Finally, consider how Alex's Lemonade Stand Foundation has embraced many tactics—and established an entire process—that makes it very simple for someone to participate. Once an individual goes to the ALSF website to sign up to run a "lemanade" (Alex's spelling) stand, he or she completes a simple form and is immediately sent a "lemanade stand in a box" set, which includes cups, banners, and balloons. Within fifteen minutes of signing up, parents (ourselves included) receive an email from ALSF public relations staff offering help to establish media contacts to promote the stand in local media. Parents are sent a press release template, which they are encouraged to personalize, not just with logistical information (time and location of their lemonade stand event), but with personal reasons for running the lemonade stand, to add authenticity, depth, and color to the story. For example, our kids included their pet issues: ending swine flu, alleviating croup, and supporting the Make-a-Wish Foundation, which made their story more personal and therefore compelling.

You want participation. The only way to get it—especially at first—is to make it easy. Always ask for participation in "bite-size" chunks or provide easy-to-follow instructions on how to contribute to a cause.

We know we're talking about some very serious topics in this book, but we can't ignore an important and possibly surprising element of social movements: the fueling effect of fun. Fun has an important place in curing cancer, solving the climate crisis, and alleviating poverty. It will make your endeavor not only more tolerable for you but also a whole lot stickier for your audience. (And, ultimately, that's what this is all about—getting your audience to do something.)

Consider the success of a viral marketing campaign from Volkswagen Sweden and DDB Stockholm, themed Rolighetsteorin, or Fun Theory, which infuses fun into everyday activities to encourage people to do the right thing (and ultimately positions Volkswagen and its new environmentally friendly BlueMotion Technologies brand by helping consumers make the leap that its cars are good for the environment as well as fun for the driver). Volkswagen thinks consumers can have it all, so to speak, and it believes that "fun is the easiest way to change people's behavior for the better."[161]

In one of the videos, Volkswagen has a crew come in late at night and turn the stairs next to an escalator at a train station into a giant piano. Suddenly, the stairs seem fun to use—so much so that the number of commuters who chose the stairs over the escalator increased by 66 percent.

In another video, the crew wires a regular trash can with motion-activated depth sound effects, so that when someone tosses in some trash, it sounds as though it's falling a long way until there's the sound of a final splat. People are so surprised and delighted they even start picking up other people's garbage to experience the fun again. Next on the campaign: a glass bottle recycling game machine. "By making driving and the world more fun, we turn the VW brand into a hero," DDB Stockholm deputy manager Lars Axelsson said in the Los Angeles Times. "Our experiments and our Fun Theory films make the world a better and more fun place to live."

Volkswagen continues to extend the fun (and its message) through social media. The video clip of people skipping the escalator in favor of composing music on the piano stairs of the Odenplan subway station in Stockholm, Sweden, got more than 500,000 views on YouTube within two weeks, and more than 1.2 million within four days. It has since been viewed nearly 12 million times.

The best nonprofits use fun, too. Consider the number of charities that organize events in which walking, running, bicycling, and other competitive activities are used to encourage people to donate time and money. Virtually every major organization devoted to medical research sponsors such events. For example, Avon Foundation Walk for Breast Cancer events take place all over the country to enable local supporters of breast cancer research to participate. In 2008 alone, nearly twenty-four thousand participants raised more than $56 million for breast cancer research, and more than $265 million has been raised by the Avon Walks since the program was founded in 2003.[162]

Alex's Lemonade Stand Foundation gets it, perhaps because it was inspired by a child's idea. (Perhaps your foundation should invite a seven-year-old to its board meetings.) Adults and children alike enjoy building their stands—which can be as simple as colorful signs taped to foldout tables—as well as the personal interactions that naturally occur as people stop to quench their thirst.

There is strong evidence connecting personal happiness with being engaged and proactive in giving back to the world. Happy individuals are much more likely to participate in activities that are adaptive, both for them and the people around them.[163] For example, positive emotions lead people to produce more ideas and think more creatively and flexibly, which in turn encourage imagination and enhance social relationships. By making the volunteer experience fun for your supporters, you increase the probability that they will continue to give—and give more—of their time and money.

Another way to harness the power of fun is game play; it taps into our innate competitiveness and desire for recognition. Just as we are wired to understand stories, so too do we seem disposed to turn situations into games. Games give your support team additional reasons to act on behalf of your cause.

Consider Foursquare (www.foursquare.com), a mobile application that mixes social, locative, and gaming elements to encourage people to explore the cities in which they live. Its goal is to "make cities easier to use," and Foursquare motivates users to do so with points, leader boards, and badges. Players are rewarded for being adventuresome—exploring different parts of the city, or visiting multiple venues in one night—and are encouraged to use the app to "check in" wherever they go, automatically notifying their friends of their locations. Many Foursquare users hook their updates into the Twitter stream or their Facebook status updates, so even non-Foursquare friends know where they are and what they're up to.

Founder Dennis Crowley recognized the potential to motivate this passionate game-oriented user base to do social good. At the 2009 Web 2.0 Summit in San Francisco, Crowley announced that Foursquare and San Francisco's Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system would partner to encourage people to use mass transit, reducing carbon emissions from cars and improving traffic conditions. BART commuters received Foursquare BART badges and also became eligible for rewards, including free BART tickets. BART also listed tips for things to do near BART stations on its Foursquare profile page (www.foursquare.com/user/SFBART). The BART partnership is the first of what Crowley hopes will be many similar socially conscious partnerships around the country, encouraging volunteerism, use of public transit, and civic responsibility.

Groupon provides another interesting example. Founder Andrew Mason observed that local merchants were willing to offer deeply discounted goods or services if they could be assured a certain amount of demand. He developed Groupon as a social commerce service to aggregate consumer demand and secure unusual discounts through a collective action platform. The result creates value—and the program is fun and engaging.

Here's an example: a restaurant offers a $45 voucher for $20 cash if seventy-five or more people pledge to buy into the deal. Once the seventy-fifth person submits her information, the deal is on. Groupon's daily deal email receives over 7.7 million impressions. The restaurant owner gets both new customers and brand exposure. And the seventy-five (or more) voucher purchasers get a great deal.

Consumers learn the deal of the day through Facebook, Twitter, and email. To stand out and avoid the customer burnout that often accompanies frequent marketing messages, Groupon hired Chicago-area comedians to write copy. Groupon grabs attention by exposing people to great local deals on things they want. Shared incentives among potential buyers and their friends lead quickly to engagement. If someone likes a deal, she tweets about it, places it on her Facebook profile, and emails it to her friends. The friends have a chance to buy into something that their friend didn't just recommend but actually committed to buy. Those friends then subscribe to Groupon, tell their friends, and so on.

Groupon is the first to bring this level of online marketing sophistication to local merchants, most of whom, the company found, were unaware of how Facebook and Twitter could help them gain new customers. The fact that merchants only pay for Groupon when an offer reaches critical mass made many of them willing to try it.

In every city, there is one primary deal of the day and one side deal of the day. By 2010, Groupon was in almost 150 major cities and had sold nearly 8 million Groupons, saving consumers about $350 million.

One of the most effective ways to encourage people to contribute to your cause—and to continue contributing over time—is to make idiosyncratic fits between their talents, skills, or interests and what you need accomplished. The idea of idiosyncratic fits—opportunities for an individual to have unique comparative advantage over others in completing a particular task or goal—has been extensively explored in many business contexts. For example, people are more likely to join a loyalty program (such as an airline frequent flyer program) if they feel they have an advantage for gaining loyalty rewards over other participants in the program.[164]

JetBlue found that when a program is compelling enough, and naturally lends itself to sharing and some friendly competition, social platforms serve as an accelerant as customers Take Action. In 2009, a few months after creating its Twitter account with the reasonable goal of reaching its frequent fliers, JetBlue executives were surprised to find themselves with more than a million followers and twittering well beyond the "TrueBlues." They considered how to take advantage of an asset they never had before—real-time access to over a million people in a new social setting. They found their answer in October 2009 when they matched Twitter with their "All You Could Jet" promotion—one ticket ($599) that would allow customers to fly as many routes as they wanted within thirty days. Fueled by Twitter, the promotion was wildly successful: the allocated tickets sold out within forty-eight hours. (They had to shut down sales a week early.) Perhaps more interestingly, without any prompting from JetBlue, the people who purchased the passes set up a Twitter account and a hashtag, #AYCJ, so they could share where they went and what they did as they flew from place to place. A few people became local celebrities, attracting news media and being welcomed upon arrival as though they were rock stars. These events became their own stories. Further, these consumers (for example, @terminalman, who went to seventy-two locations; http://www.wired.com/autopia/tag/terminal-man/) started to connect with each other, tweeting with each other and becoming authentic embodiments of the JetBlue brand. JetBlue invited twelve of the most prolific twitterers to its annual leadership conference to talk about how this became its own culture, and how they individually used the experience.

To motivate people to act on behalf of your cause, then, you need to match their skills, talents, or interests with your needs. Whether being creative, as with designing new outfits in Gap's Born to Fit initiative; providing an endorsement or reference; or making a physical donation, as when people give blood because they have a needed blood type,[165] the more that people feel they have uniquely contributed, the happier and more satisfied they will be—and the more likely they are to spread the word or return to contribute more.

It is imperative to prepare for openness, which means creating a platform others can add to, take from, and alter themselves. How do you create this necessary culture of sharing, and how do you build trust? One critical step is to design with the principle of sustained transparency. This is easier said than done. However, if you design for openness at the start, it becomes significantly easier to continue.

First, perceptions of transparency don't perfectly correlate with actual transparency. And indeed most companies believe they are far more transparent than consumers think they are. This gap between corporate perceptions and consumer perceptions is known as the image-identity gap. Psychological research shows a similar bias for individuals, who tend to feel that their underlying motives are much more open and transparent than others find them.[166]

A second critical step to being open is based on design thinking principles. That is, if you ideate, prototype, and test frequently, you will—by definition—be designing for feedback. Showing people that they're actually making a difference is arguably the most critical aspect of encouraging action. The closer you come to real time in providing feedback, the better. People want to know they're moving, however incrementally, toward their goal. Show them the results of their actions (however small) as quickly as possible to retain their interest and encourage them to go even further.

Everywun.com provides an interesting example. Everywun is a nonprofit organization that offers fun, cost-free ways for individuals to contribute to a broad range of causes. Volunteers might collect books to send to Africa, shelter stray dogs and cats, or plant trees. Everywun posts their work immediately on its website, so volunteers can see how their efforts are helping their chosen cause. Volunteers also receive virtual badges to put on their Everywun profile pages or personal websites, depicting the causes they've contributed to, as well as a real-time metric that shows the good they've accomplished, such as the CO2 emissions mitigated because of the number of trees they've planted.

Showing concrete results is critical, because nothing breeds success like success. Within just eight months of inception, Everywun.com was able to announce that membership had passed the 10,000 mark; that the website was experiencing monthly page views of 540,000; that Twitter followers numbered 16,000; and that Everywun electronic badges posted online by volunteers numbered more than 5,000.

Being open and choosing the right metrics to enable feedback are the final design principles for wing 4 because your ability to execute them rests on successful implementation of the skills you've already learned in the previous wings. Furthermore, they bring together the entire framework. Specifically, the metrics you choose to measure your cause must link wing 4 (Take Action) to wing 1 (Think Focused). They should reflect your project's specific goal and dramatize how that goal is incrementally closer than before—as a result of individual contributions. If possible, place the current status of your project in a historical context. One effective strategy is to use a timeline that depicts progress at specific time intervals or important milestones.

Feedback is motivating not only for users but for you: it provides the information you need to refine your effort and the energy you need to keep going.

In summary, ideate frequently, operate cheaply, and put in place online analytical tools to track performance. If people are unhappy, ask why, and acknowledge their feedback. If people are happy, ask why, and then make the campaign iterative with replicable tactics and usable templates. The fourth and final wing in the Dragonfly Model, Take Action, is the culmination of everything you've done to date to get others to support you in meeting your goals. By concentrating on the all-important "ask," using the strategies outlined in this chapter, you can successfully close the loop on your earlier successes: focusing your efforts, grabbing attention, and engaging users by spurring them to take action. With the right set-up, one small ask can garner great, perhaps world-changing results.