The Right to Receive an Honest Day’s Work

The Fair Labor Standards Act and Other Wage-and-Hour Issues

I was once asked the following question: “If you could press a button and instantly vaporize one sector of employment law, which would it be?” My answer, without a moment’s hestitation, was the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)—the federal law that governs how many hours employees work and how employers pay them for those hours.

We need to vaporize the FLSA because compliance is impossible. Congress enacted the FLSA during the Great Depression to combat the sweatshops that had taken over our manufacturing sector. In the 70 plus years that have passed, it has evolved via a complex web of regulations and interpretations into an anachronistic maze of rules with which even the best-intentioned employer cannot hope to comply. I would bet any employer in this country a free wage-and-hour audit that I could find an FLSA violation in its pay practices. A regulatory scheme that is impossible to meet does not make sense to keep alive.

Do not misinterpret my remarks. I am all in favor of employees receiving a full day’s pay for a full day’s work. What employers and employees need, though, is a streamlined and modernized system to ensure that workers are paid a fair wage.

Workplace email is but one example that illustrates my point. Our iPhoned workforce raises an interesting wage-and-hour question: is time spent outside the office emailing compensable time under the FLSA? Because employers provide these technological tools with the understanding that employees will use them during off-duty hours, there is a good argument that the time spent using them is probably compensable. Yet we are stuck shoehorning the payment of time spent reading emails away from work into a regulatory schema drafted decades before mobile devices were even a dream in a science fiction book.

Even if reading and responding to work-related email are work-related (and they likely are), I am not convinced that employers should have to pay for any time spent performing these tasks. Most messages can be read in a matter of seconds or, at most, a few short minutes. The FLSA calls such time de minimus and does not require compensation for it. “Insubstantial or insignificant periods of time beyond the scheduled working hours, which cannot as a practical administrative matter be precisely recorded for payroll purposes, may be disregarded.”1 This is good; think of the administrative nightmare of an HR or payroll department having to track, record, and pay for every fraction of a minute an employee spends reading an email.

The safest course of action for employers is to provide smart phones only to exempt employees. If companies, however, are going to provide these devices to nonexempt employees, they should have a policy in place stating that employees who check emails off the clock do so of their own choice and that the time spent will not be compensated. Of course, such a policy is not foolproof, and businesses that make it possible for employees to remain connected when off duty will have to take the risk that the time might count as hours worked.

Nevertheless, we are stuck with the FLSA and the maze of rules and regulations that travel with it. The issue that employers face when dealing with these issues is that employees typically do not bring these claims on an individual basis. They assert their wage-and-hour rights on a class-wide or collective basis, significantly increasing employers’ risks.

Most companies cannot afford the risk of a big judgment in a wage-and-hour class action. Indeed, the real risk in defending these cases is the leverage plaintiffs gain from the threat of big judgments, and the seven-figure settlements that often result.

__________

1 29 C.F.R. § 785.47.

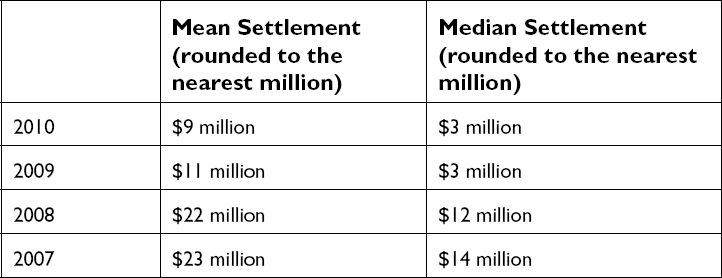

Consider the results of a recent study of wage-and-hour settlements conducted by NERA Economic Consulting:2

While the overall settlement values have decreased over the last four years, the numbers are still dramatic. Few companies can afford to write a check for $3 million to fund a class action settlement. Yet, this is the prospect that companies face when they ignore their obligations under the wage-and-hour laws.

As a general matter, pursuant to the FLSA, employers must pay employees a minimum wage, and they must further pay all nonexempt employees for all time worked, including a one-and-one-half overtime premium for all hours in a week worked in excess of 40. This rule, however, merely begs the following questions: 1) what does it mean to be “nonexempt”; and 2) what is “time worked”? This chapter will provide answers to those and other sticky questions.

Exemptions

The FLSA separates employees into two general categories: exempt and nonexempt. The distinction is important. If an employee is nonexempt, the FLSA requires that the employer compensate the employee at the premium rate of one-and-one-half times the regular rate of pay for any hours worked in excess of 40 in any given work week. Exempt employees, on the other hand, are called such because they are exempt from this overtime pay requirement, and can work as many hours as they and their employers see fit without any premium pay for overtime hours (hours in excess of 40 in a work week).

__________

2 Mondaq Employment and HR, “United States: Recent Trends in Wage and Hour Settlements,” http://www.mondaq.com/unitedstates/article.asp?articleid=129638, April 19, 2011.

FLSA exemptions are fact-specific and always a judgment call. Because it is a subjective decision, classifications may not always be correct. In fact, I once represented a company that had its entire employee classification system undone by a Department of Labor (DOL) audit. The company had used a human resources consultant to establish their exemptions, and the DOL concluded that more than 80% of the employees had been misclassified and were owed substantial unpaid overtime. There are no hard and fast rules, but merely guidelines that fall under some broad-based categories.

Administrative Exemption

Nothing in employment law has a more misleading name than the administrative exemption in the FLSA. Employers routinely misbelieve that if an employee performs administrative tasks, that employee is exempt from being paid overtime under the FLSA. In fact, the administrative exemption only applies to a narrow group of employees—those whose primary duty is the performance of office or nonmanual work directly related to the management or general business operations of the employer or the employer’s customers and which includes the exercise of discretion and independent judgment with respect to matters of significance.

What does it take for an employee to qualify under the FLSA’s administrative exemption?

To qualify for the administrative employee exemption, all of the following qualifications must be met:

- The employee must be compensated on a salary or fee basis (as defined in the regulations) at a rate not less than $455 per week;

- The employee’s primary duty must be the performance of office or nonmanual work directly related to the management or general business operations of the employer or the employer’s customers; and

- The employee’s primary duty includes the exercise of discretion and independent judgment with respect to matters of significance.

“Primary duty” means the principal, main, major or most important duty that the employee performs, with the major emphasis on the character of the employee’s job as a whole.

Work “directly related to management or general business operations” includes, but is not limited to, work in functional areas such as tax; finance; accounting; budgeting; auditing; insurance; quality control; purchasing; procurement; advertising; marketing; research; safety and health; personnel management; human resources; employee benefits; labor relations; public relations; government relations; computer network, Internet and database administration; legal and regulatory compliance; and similar activities. It’s work directly related to assisting with the running or servicing of the business, as distinguished from working on a manufacturing production line or selling a product in a retail or service establishment. It also covers employees acting as advisors or consultants to their employer’s clients or customers.

The exercise of discretion and independent judgment involves the comparison and the evaluation of possible courses of conduct and acting or making a decision after the various possibilities have been considered. It implies that the employee has authority to make an independent choice, free from immediate direction or supervision. Factors to consider include, but are not limited to:

- Whether the employee has authority to formulate, affect, interpret, or implement management policies or operating practices;

- Whether the employee carries out major assignments in conducting the operations of the business;

- Whether the employee performs work that affects business operations to a substantial degree;

- Whether the employee has authority to commit the employer in matters that have significant financial impact; and

- Whether the employee has authority to waive or deviate from established policies and procedures without prior approval.

“Matters of significance” refers to the level of importance or consequence of the work performed.

Examples of some professions that the DOL has found could qualify for the administrative exemption include mortgage loan officers,3 insurance agents,4 sales managers,5 marketing analysts,6 purchasing agents,7 financial services registered representatives,8 and loss-prevention managers.9

__________

3 United States Department of Labor, “Opinion Letters—Fair Labor Standards Act,” http://www.dol.gov/whd/opinion/FLSA/2006/2006_09_08_31_FLSA.htm, Sept. 8, 2006

These categories, however, are merely guidelines to observe and not dogma to follow. Whether an administrative employee is administratively exempt is a fact-intensive analysis, determined on an employee-by-employee basis, even within the same job category within the same organization.

And the rules are changing. In 2010, the DOL issued a game-changing opinion, in which it concluded: “Employees who perform the typical job duties of a mortgage loan officer do not qualify” as exempt administrative employees:10

A careful examination of the law as applied to the mortgage loan officers’ duties demonstrates that their primary duty is making sales and, therefore, mortgage loan officers perform the production work [as opposed to administrative work] of their employers.

This pronouncement is significant because it is a stark departure from conventional wisdom applying the administrative exemption.

Executive Exemption

What does it take for an employee to qualify as exempt under the Executive Exemption of the FLSA? As is the case with the administrative exemption, job titles do not determine exempt status. For an exemption to apply, an employee’s specific job duties and salary must meet all the requirements of the DOL’s regulations.

To qualify for the executive employee exemption, all of the following tests must be met:

__________

4 United States Department of Labor, “Opinion Letters—Fair Labor Standards Act,” http://www.dol.gov/whd/opinion/FLSA/2009/2009_01_16_28_FLSA.htm, Jan. 16, 2009.

5 United States Department of Labor, “Opinion Letters—Fair Labor Standards Act,” http://www.dol.gov/whd/opinion/FLSA/2009/2009_01_14_04_FLSA.htm, Jan. 14, 2009.

6 United States Department of Labor, “Opinion Letters—Fair Labor Standards Act,” http://www.dol.gov/whd/opinion/FLSA/2008/2008_04_21_03_FLSA.htm, Apr. 21, 2008.

7 United States Department of Labor, “Opinion Letters—Fair Labor Standards Act,” http://www.dol.gov/whd/opinion/FLSA/2008/2008_03_06_01_FLSA.htm, Mar. 6, 2008.

8 United States Department of Labor, “Opinion Letters—Fair Labor Standards Act,” http://www.dol.gov/whd/opinion/FLSA/2006/2006_11_27_43_FLSA.htm, Nov. 27, 2006.

9 United States Department of Labor, “Opinion Letters—Fair Labor Standards Act,” http://www.dol.gov/whd/opinion/FLSA/2006/2006_09_08_30_FLSA.htm, Sept. 8, 2006.

10 United States Department of Labor, “Wage and Hour Division,” http://www.dol.gov /WHD/opinion/adminIntrprtn/FLSA/2010/FLSAAI2010_1.htm, Mar. 24, 2010.

- The employee must be compensated on a salary basis (as defined in the regulations) at a rate not less than $455 per week;

- The employee’s primary duty must be managing the enterprise, or managing a customarily recognized department or subdivision of the enterprise;

- The employee must customarily and regularly direct the work of at least two or more other full-time employees or their equivalent (such as one full-time and two part-time employees, or four part-time employees); and

- The employee must have the authority to hire or fire other employees, or the employee’s suggestions and recommendations as to the hiring, firing, advancement, promotion or any other change of status for other employees must be given particular weight.

“Management” includes, but is not limited to, activities such as interviewing, selecting, and training of employees; setting and adjusting their rates of pay and hours of work; directing the work of employees; maintaining production or sales records for use in supervision or control; appraising employees’ productivity and efficiency for the purpose of recommending promotions or other changes in status; handling employee complaints and grievances; disciplining employees; planning the work; determining the techniques to be used; apportioning the work among the employees; determining the type of materials, supplies, machinery, equipment or tools to be used or merchandise to be bought, stocked and sold; controlling the flow and distribution of materials or merchandise and supplies; providing for the safety and security of the employees or the property; planning and controlling the budget; and monitoring or implementing legal compliance measures.

“Customarily and regularly” means greater than occasional but not necessarily all the time. For example, work normally done every workweek is customarily and regularly, but isolated or one-time tasks are not.

Factors to be considered in determining whether an employee’s recommendations as to employment decisions are given “particular weight” include whether it is part of the employee’s job duties to make such recommendations and the frequency with which such recommendations are made, requested, and relied upon. An employee’s recommendations may still be deemed to have “particular weight” even if the employee is not the ultimate decision maker.

Salespeople

The FLSA has two different exemptions that could cover salespeople— the outside sales employee exemption and the commissioned retail employee exemption. If an employee qualifies for either of these exemptions, that employee is not owed overtime for any hours worked in excess of 40 in any given work week.

To qualify for the outside sales employee exemption, both of the following must be met:

1. The employee’s primary duty must either be making sales or obtaining orders or contracts for services or for the use of facilities for which a consideration will be paid by the client or customer; and

2. The employee must customarily and regularly be engaged away from the employer’s place or places of business.

Because sales employees are often commissioned (at least in part), there is no salary requirement with this exemption. Outside sales typically do not include sales made by mail, telephone, or the Internet. For example, this exemption does not cover telemarketers.

![]() Note: The outside sales exemption does not cover telemarketers or those soliciting orders over the Internet.

Note: The outside sales exemption does not cover telemarketers or those soliciting orders over the Internet.

To qualify for the commissioned retail employee exemption, all three of the following requirements must be met:

1. The employee must be employed by a retail or service establishment;

2. The employee’s regular rate of pay must exceed one and one-half times the applicable minimum wage; and

3. More than half of the employee’s earnings must be in the form of commissions.

Computer Employees

One of the FLSA’s lesser-known exemptions is the computer employee exemption.

For an employee to qualify for the computer employee exemption, the employee must either be paid a salary of at least $455 per week or an hourly rate of at least $27.63. The employee must be employed as a computer systems analyst, computer programmer, software engineer, or other similarly skilled worker in the computer field.

Additionally, the employee’s primary duty must fall into one of the following four categories:

1. The application of systems analysis techniques and procedures, including consulting with users to determine hardware, software, or system functional specifications;

2. The design, development, documentation, analysis, creation, testing, or modification of computer systems or programs, including prototypes, based on and related to user or system design specifications;

3. The design, documentation, testing, creation or modification of computer programs related to machine operating systems; or

4. A combination of the aforementioned duties, the performance of which requires the same level of skills.

This exemption does not include:

- Employees engaged in the manufacture or repair of computer hardware and related equipment.

- Employees whose work is highly dependent upon, or facilitated by, the use of computers and computer software programs (such as engineers, drafters, and others skilled in computer-aided design software) but who are not primarily engaged in computer systems analysis and programming.

Internships

One area that has received a lot of recent attention and is ripe for wage-and-hour problems is unpaid internships.

The DOL uses a six-factor test to determine whether an intern is an employee in disguise and therefore one who must be paid. All six of the following factors must be met before an employer can legally refuse pay to an intern:

1. Is the training similar to what would be given in a vocational school or academic educational instruction?

2. Is the training for the benefit of the trainees or students?

3. Do the trainees or students work under the close observation of regular employees without displacing them?

4. Does the employer derive no immediate advantage from the activities of the trainees or students, and on occasion are the employer’s operations actually impeded?

5. Are the trainees or students not necessarily entitled to a job at the conclusion of the training period?

6. Does the employer and the trainees or students understand that the trainees or students are not entitled to wages for the time spent in training?

And “interns” are starting to fight back. According to Nancy J. Leppink, the acting director of the DOL’s Wage and Hour Division:

If you’re a for-profit employer or you want to pursue an internship with a for-profit employer, there aren’t going to be many circumstances where you can have an internship and not be paid and still be in compliance with the law.11

Consider the following examples of real lawsuits filed by interns against their employers in the past year.

- A former unpaid intern for the Charlie Rose show has filed a lawsuit against the host and his production company. According to Steven Greenhouse at the New York Times Media Decoder blog,12 the former intern claims that she was not paid for the 25 hours a week she worked in the summer of 2007. The lawsuit seeks a class action on behalf of all unpaid interns who have worked for the show since March 2006.

- A former unpaid intern for the fashion magazine Harper’s Bazaar filed a similar lawsuit, claiming she worked full-time without any pay. Steven Greenhouse at the New York Times Media Decoder blog quotes the lawyer who filed the lawsuit, “Unpaid interns are becoming the modern-day equivalent of entry-level employees, except that employers are not paying them for the many hours they work.”13

- Two interns who worked on the film Black Swan have sued Fox Searchlight Pictures making similar claims.14

__________

11 Steven Greenhouse, “The Unpaid Intern, Legal or Not,” The New York Times, B1 (Apr. 3, 2010).

12 Steven Greenhouse, “Former Intern at ‘Charlie Rose’ Sues, Alleging Wage Law Violations,” http://mediadecoder.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/03/14/former-intern-at-charlie-rose-sues-alleging-wage-law-violations/?hp, March 14, 2012.

In response to this spate of lawsuits, publishing giant Condé Naste has revised its guidelines for the use of unpaid interns. Condé Naste’s interns:

- Cannot stay at the company for more than one semester per calendar year.

- Must complete an HR orientation about where to report mistreatment or unreasonably long hours.

- Cannot work past 7 PM.

- Must receive college credit.

- Must be assigned an official mentor.

- Cannot run personal errands.

- Will be paid stipends of $550 per semester.15

These procedures might not be right for your organization. But they highlight that you need to be thinking about these issues if you are a private sector, for-profit entity using, or considering using, interns. The rules haven’t changed; only they are now more widely known and are being enforced.

Employers that use unpaid interns should pay careful attention to this issue. It is far better to scrutinize interns under the DOL’s six factors before the agency, or a group of plaintiffs, swoop in and do it for you. It is even better to formalize the relationship in a written internship agreement that formally spells out how each of these six questions is answered in your favor. Or maybe it is best simply to assume that except in rare cases, there is no such animal as an “unpaid intern,” and you should simply accept the fact that if you are going to label entry-level employees as interns, you need to pay them for their services.

__________

13 Steven Greenhouse, “Former Intern Sues Hearst Over Unpaid Work and Hopes to Create a Class Action,” http://mediadecoder.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/02/01/former-intern-sues-hearst-over-unpaid-work-and-hopes-to-create-a-class-action/, February 1, 2012.

14 Paul Davidson, “Fewer unpaid internships to be offered,” http://www.usatoday.com/money/workplace/story/2012-03-07/summer-internships-paid-unpaid/53404886/1, March 7, 2012.

15 Rebecca Greenfield, “Conde Nast’s Internship Reforms Show How Bad the System Really Is,” http://www.theatlanticwire.com/national/2012/03/conde-nasts-unpaid-internship-reforms-show-how-bad-system-really/49830/, March 13, 2012.

Employee or Independent Contractor?

Another potential classification pitfall is the key distinction between an employee and an independent contractor. If companies had their choice, they would classify all workers as “independent contractors.” As a contractor, the worker is exempt from discrimination laws, unemployment laws, workers’ compensation laws, and wage-and-hour laws. Also, the employer does not have to pay payroll or other taxes on anyone properly classified as a contractor.

For these same reasons, though, misclassifying an employee as a contractor carries significant implications. You could expose yourself to discrimination or other liability. You could be responsible for unpaid wages such as overtime. And, perhaps most importantly, the IRS will come looking (and, trust me, it will come looking) for its share of taxes you did not pay as a result of the misclassification.

There are four things every business should know about this important distinction between an employee and an independent contractor.

First, the IRS uses three characteristics to determine the relationship between businesses and workers and whether the workers are employees or independent contractors:

1. Behavioral Control: Does the business have a right to direct or control how the work is done through instructions, training or other means?

2. Financial Control: Does the business have a right to direct or control the financial and business aspects of the worker’s job?

3. Type of Relationship: How do the workers and the business owner perceive their relationship?

If you have the right to control or direct the tasks the worker performs but also how they are to be done, then the workers are most likely employees. If, however, you can direct or control only the result of the work done—but not the means and methods of accomplishing the result—then your workers are probably independent contractors.

Because of the expensive penalties you can face for unpaid taxes on misclassified employees, this distinction is one that you should not take lightly.

Working Time

What does work time entail? Possibly more than you think. The distinction between work time and nonwork time is significant. Not only must employers pay employees for all working time, but working time must be counted for purposes of determining whether an employee worked more than 40 hours in a given work week and is eligible for overtime compensation. For this reason, misclassifying working time as nonworking time can be an expensive mistake.

Donning and Doffing

Donning and doffing is a fancy way to say putting on and taking off. In wage-and-hour land, it always refers to putting on protective clothing before a shift starts and taking off protective clothing after a shift ends. Donning and doffing is one of the more difficult, and controversial, rules the wage-and-hour laws present.

In 2010, The DOL’s Wage and Hour Division issued an administrator’s interpretation finding that that the time spent by employees donning and doffing protective equipment required by law is compensable and must be paid.16 It also means that an employee’s workday begins with the donning of required protective equipment and ends with its doffing and all of the time in-between is payable work time.

Courts are beginning to fall in line with this administrator’s interpretation . For example, in Franklin v. Kellogg Company,17 the Sixth Circuit concluded that the time spent walking between the locker room and the time clock after donning and before doffing protective gear is compensable working time.

The Court started with restating some general principles. Federal wage-and-hour laws define the “workday” as “the period between the commencement and completion on the same workday of an employee’s principal activity or activities.” Generally, time spent walking to and from a time clock is not compensable. During a “continuous workday,” however, the FLSA finds that “any walking time that occurs after the beginning of the employee’s first principal activity and before the end of the employee’s last principal activity . . . must be compensated.” Principal activities are those that are an integral and indispensable part of the activities that the employee is employed to perform.

__________

16 United States Department of Labor, “Wage and Hour Division Administrator’s Interpretation,” http://www.dol.gov/WHD/opinion/adminIntrprtn/FLSA/2010/FLSAAI2010_2.htm, June 16, 2010.

17 619 F. 3d 604 (6th Cir. 2010).

Kellogg required all hourly employees to wear company-provided uniforms, including pants, snap-front shirts bearing the Kellogg logo and employee’s name, slip-resistant shoes, and safety equipment (hair and beard nets, safety glasses, earplugs, and bump caps). Kellogg mandated that employees change into their uniform and safety equipment upon arriving at the plant and to change back into their regular clothes before leaving the plant so that the uniform and safety equipment could be washed and cleaned. Kellogg claimed that changing into and out of the uniform and safety equipment is not “integral and indispensable” (and is therefore not compensable) under the FLSA.

The Sixth Circuit disagreed, applying a broad interpretation of what is necessary for an employee to perform his or her job. The court evaluated these three factors—(1) whether the activity is required by the employer; (2) whether the activity is necessary for the employee to perform his or her duties; and (3) whether the activity primarily benefits the employer—and concluded:

[D]onning and doffing the uniform and equipment is both integral and indispensable. First, the activity is required by Kellogg. Second, wearing the uniform and equipment primarily benefits Kellogg. Certainly, the employees receive protection from physical harm by wearing the equipment. However, the benefit is primarily for Kellogg, because the uniform and equipment ensures sanitary working conditions and untainted products. Because Franklin would be able to physically complete her job without donning the uniform and equipment . . . it is difficult to say that donning the items are necessary for her to perform her duties. Nonetheless . . . we conclude that donning and doffing the uniform and standard equipment at issue here is a principal activity. Accordingly, under the continuous workday rule, Franklin may be entitled to payment for her post-donning and pre-doffing walking time.

In other words, as long as the donning and doffing is mandatory and provides some benefit to the employer (here, a sanitary workplace), it is compensable working time and needs to be paid.

Travel Time

As a general rule, time spent traveling from home to work and back again to home does not have to be compensated.

Like all rules, however, there are exceptions.

1. Time spent by an employee traveling as part of the principal work activity, such as travel from job site to job site during the workday or travel between customers, is counted as hours worked and must be paid.

2. Travel that keeps an employee away from home overnight must also be compensated, but only when the travel time occurs during an employee’s normal workday. Thus, if an hourly employee’s normal workday runs from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., only out-of-town travel during those hours must be paid. This rule applies whether the travel occurs on a regular workday or a normal day off. So, if the same employee travels during regular work hours on a Sunday, but regularly has Sunday off, the time must still be paid.

3. Out-of-town travel that is completed all in one day receives different treatment. The employee is compensated for the travel from home to the out-of-town worksite, less the amount of time it would have taken the employee to drive to work during a regular workday. The rationale is that the employee should not have to be compensated for the time he or she would have spent traveling to and from work on a regular workday.

Meal and Rest Periods

While some state laws require meal and rest periods, there is no federal requirement that employers provide any breaks during the work day, paid or unpaid. What federal law does provide, however, is whether meal and rest breaks, when given, are counted as “hours worked.” This distinction is important. If time is counted as “hours worked,” it goes into the calculation of time worked during the workweek for consideration of whether the employee has crossed the 40-hour threshold for overtime pay.

- Rest periods, which are considered breaks of 20 minutes or less, are counted as hours worked whether or not the break is paid. Rest breaks are customarily paid, and if they must be counted as work hours, they might as well be paid.18

- A bona fide meal period, however, is not considered hours worked. To be a bona fide meal period the employee must be totally relieved of his or her work duties. According to the DOL: “The employee is not relieved if he is required to perform any duties, whether active or inactive, while eating.”19

What does it mean to be “totally relieved of one’s duties?” Most courts apply the “predominant benefit” test to determine whether an employee’s meal period is compensable. Under this test, the employee bears the burden to prove that the normally noncompensable meal period should be compensable because it is spent predominantly for the employer’s benefit. The key inquiry is whether the employee engaged in the performance of any substantial duties during the lunch break. As long as the employee can pursue his or her mealtime adequately and comfortably, is not engaged in the performance of any substantial duties, and does not spend time predominantly for the employer’s benefit, the employee is not entitled to compensation under the FLSA for a lunch break. Thus, for example, it may not matter if an employee is “on call” during a meal break, unless the employee’s meal is actually disturbed.

__________

18 29 C.F.R. § 785.18.

19 29 C.F.R. § 785.19.

As with most employment law issues, it is best to set out expectations about meal breaks in a clear policy. For example:

Each employee is entitled to a 30-minute lunch break each day. That lunch break is unpaid. Because it is unpaid, it is the employee’s time to spend as he or she sees fit. Employees should expect to enjoy their lunch breaks without interruption by a coworker, supervisor, or manager, except in the event of an emergency that requires an employee to cut his or her lunch break short. No employee is permitted to work through a lunch break without the prior approval of his or her immediate supervisor.

Of course, such a policy is only as good as its enforcement.

Telecommuting

Could telecommuting employees present the next wave of wage-and-hour litigation? There are as many as 50 million Americans who work remotely at least part of the time. Because many of these telecommuters will be nonexempt, how employers track their hours and pay their wages has the potential to cause problems.

As I’ve already discussed, nonexempt employees must be paid for all time worked, including overtime for hours in a week worked in excess of 40. Employers must also maintain a tracking system that accurately records this compensable work time. Because telecommuters work outside of the workplace, and often during odd hours, they present special problems for accurately tracking the amount of time spent working.

If your business is going to employ telecommuters, you should take appropriate measures—in a telecommuting policy or contract—to control the time spent working:

- Employers should clearly communicate to the employee the number of hours expected to be worked each week.

- Telecommuting employees must be required to accurately track all time spent working. Whatever the system used (pen and paper timesheets, Excel spreadsheets, timekeeping software, or electronic logins or other “punches”), employees must understand that they will only be paid for the amount of time reported.

- Because telecommuting employees are working without direct supervision, all submitted work should be reviewed by a manager or supervisor to ensure that the work performed correlates to the amount of working time reported. An employer cannot dock time or refuse to pay an employee for time spent working. However, an employer can take away an employee’s ability to telecommute if the employee proves to be irresponsible or abuses the telecommuting privilege.

Telecommuting may or may not be “the next big thing” in wage-and-hour litigation. It raises, however, enough unique wage-and-hour issues that inattentive employers who ignore these issues risk getting burned.

Calculating the Regular Rate of Pay for Overtime Purposes

If you pay your employees a straight hourly wage, the calculation of their overtime rate for any hours worked in any week in excess of 40 is straightforward. You take the hour rate and multiply by 1.5 and pay that premium for all hours over 40 in a given week. If, however, you pay you nonexempt employees other than on an hourly basis, the calculation becomes much more complicated. This section highlights some of these issues.

Salaried, Nonexempt Employees

An employer has two choices in how to pay overtime to a salaried nonexempt employee: by a fixed workweek or based on a fluctuating workweek. For reasons that will be illustrated below, the latter is a much more cost-effective option for most employers.

By a fixed workweek:

1. If the employee is paid solely a weekly salary, his regular hourly rate of pay—on which time and a half must be paid—is computed by dividing the salary by the number of hours that the salary compensates. For example, If an employee is hired at a weekly salary of $525, which is intended to be compensation for a regular 35-hour work week, the employee’s regular rate of pay will be $15 per hour ($525 / 35). If that employee works overtime (more than 40 hours in a given workweek), he or she will have to be paid $22.50 for each overtime hour worked. Thus, in a 45-hour week, the employee would be paid $637.50.

2. Where the salary covers a period longer than a workweek, such as a month, it must be reduced to its workweek equivalent. Thus, for example, a monthly salary can be converted to a weekly salary by multiplying it by 12 and dividing by 52. Once the regular weekly salary is calculated, the analysis is the same as above.

On a fluctuating workweek:

1. Often, the number of hours a salaried employee works will vary from week to week, depending on the given needs of the job. One might work 40 hours one week, 45 the next, and 38 the week after that. An employer and employee can agree that a salary will cover all straight time pay for all hours worked in a given week, no matter how few or how many. Payment for overtime hours at one-half such rate satisfies the overtime pay requirement because such hours have already been compensated at the straight time regular rate as part of the salary. And that overtime premium will vary from week to week depending on the number of hours worked.

2. To use this method of overtime calculation, there has to be a clear mutual understanding between the employer and employee that the fixed salary is compensation (apart from overtime premiums) for the hours worked each workweek, whatever the number.

3. This “fluctuating workweek” method of overtime payment may not be used unless the salary is sufficiently large to ensure that there will be no workweeks in which the employee’s average hourly earnings from the salary fall below the minimum wage.

4. For example, taking our $525 salary from above, in a 45-hour workweek, the hourly rate would be $11.66 ($525/45). But for the extra 5 hours, the employee would only be owed an additional $29.15 ($5.83 x 5), for a total weekly compensation of $554.15. The fluctuating workweek saves this employer $83.35 in wages for the week. Thus, it is easy to see why the fluctuation workweek is the preferred method for calculating overtime premiums for salaried nonexempt employees.

Nonexempt Commissioned Employees

Only a small subset of commissioned employees is exempt from the FLSA’s overtime provisions. For the majority of employees who are paid wholly or in part by commissions, the FLSA presents a complicated calculus of rules and regulations that employers must follow to properly account and pay overtime premiums for hours worked in excess of 40 in any workweek.

The key question for commissioned employees is how one computes the “regular rate of pay” for purposes of calculating the proper overtime premium to apply to commissions paid.

If a commission is paid on a weekly basis, the calculation is fairly basic. The commission is added to any other earnings for that workweek. The total is then divided by the number of hours worked during that week to obtain the employee’s regular rate for that particular workweek. The employee must then be paid overtime compensation of one-half of that rate for each hour worked in excess of 40 for that week.

It gets more complicated, however, if the calculation and payment of the commission cannot be completed until sometime after the regular payday for the workweek. In this case, the employer may disregard until later the commission in computing the regular hourly rate and pay overtime exclusive of the commission. However, when the commission is ultimately paid, the employer has to go back and recalculate the overtime premium for each workweek covered by the deferred or delayed commission payment. The employer must apportion the commission back over the workweeks of the period during which it was earned. The employee must then receive additional overtime compensation for each week during the period in which he worked in excess of 40 hours.

It gets even more complicated if it is not possible or practical to allocate the commission among the workweeks per the amount of commission actually earned or reasonably presumed. In this case, the DOL permits employers to choose from one of two different methods to fairly and equitably account for overtime premiums.

1. Allocation of equal amounts each week. Under this method, the employer will assume that the employee earned an equal amount of commission for each week of the period covered and compute any additional overtime compensation based on that pro rata amount. For example:

- For a commission paid monthly, multiply the commission by 12 and divide by 52 to obtain the amount attributable for each week of that month.

- For a commission paid semimonthly, multiply by 24 and divide by 52.

- For a commission that covers a specific number of workweeks, divide the total commission paid by the number of weeks it covers.

- Once the pro rata weekly commissions are determined, simply divide that amount by the total number of hours worked to obtain the increase in the hourly rate. The employee is then owed one-half of that increase for each hour worked in excess of 40 for a given week.

2. Allocation of equal amounts to each hour worked. Sometimes, there are facts that make it inappropriate to assume equal commission earnings for each workweek (such as when the number of hours worked each week varies widely). In such cases, the employer can assume that the employee earned the same amount of commission for each hour worked during the computation period. The total commission payment should be divided by the total number of hours to determine the amount of the increase in the regular rate. To determine the amount of additional overtime compensation owed for the period, multiply one-half of the figure by the total number of overtime hours worked by the employee for all workweeks during the covered period.

Bonus Payments

Year-end bonus payments could count as part of a nonexempt employee’s regular rate of pay, thereby increasing the overtime premium owed to that employee. Given the current economic state, fewer companies are paying bonuses, but these rules are important to heed when bonuses are paid to hourly and salaried nonexempt employees.

Section 7(e) of the FLSA requires the inclusion in the regular rate of pay all remuneration for employment except seven specified types of payments. Bonuses that do not qualify for exclusion from the regular rate under one of the seven exceptions must be totaled with other earnings to determine the regular rate upon which the overtime premium rate must be based.

A bonus could fall under one of two exceptions: discretionary payments, or gifts made at Christmas time or on other special occasions. Each of these two categories, however, has specific criteria that must be met before a bonus payment can be excluded from the regular rate.

Discretionary Bonus Payments

For a bonus to qualify for exclusion as a discretionary bonus, the employer must retain discretion both as to the fact of payment and as to its amount. Consider the following examples:

- An employer promises at the beginning of the year to pay a bonus at year-end in some undetermined amount. It has given up discretion as to the fact of the bonus, but not as to its amount.

- An employer promises employees that they will receive a bonus based on some mathematical formula, but only if the company determines that it can afford to make the payments at that time. It has given up discretion as to the bonus’s amount, but not as to the fact of payment.

In both examples, the bonus is not discretionary, albeit for opposite reasons. For a bonus to be truly discretionary, the employer would have to retain complete discretion as whether to make the payment, and if so, in what amount. The employer cannot rely on any prior promise or agreement in making the payment or determining its amount.

Gifts, Christmas, and Special Occasion Bonuses

To qualify for exclusion under this exception, the bonus must be a bona fide gift. If it is measured by hours worked, is measured by production or efficiency, is so large that employees would reasonably consider it part of their wages for hours worked, or is paid pursuant to some agreement or policy, then the bonus cannot be considered to be a gift.

According to the DOL, the following circumstances will not disqualify a year-end payment as a gift:

- If an employer pays it with such regularity that employees are led to expect it from year to year.

- The amounts paid vary among employees or groups or are tied to salary, wage, or length of service. For example, a Christmas bonus paid in the amount of two weeks’ salary to all employees and an equal additional amount for each five years of service with the firm would be excludable from the regular rate.

The key factors are whether there is a contract and whether the amount is specifically tied to hours worked, production, or efficiency. If so, you must add the amount to the regular rate of pay.

Calculating the Regular Rate with a Bonus Payment

Where a bonus payment is considered a part of the regular rate at which an employee is employed, it must be included in computing the regular hourly rate of pay and overtime compensation. For purposes of calculating the regular rate of pay, the bonus does not have to be included in its entirety in the week it is paid. Instead, an employer can apportion the bonus amount back over the workweeks of the period during which it was earned. The employee must then receive an additional amount of compensation for each workweek that he worked overtime during the period equal to one-half of the hourly rate of pay allocable to the bonus for that week multiplied by the number of statutory overtime hours worked during the week. If it is impossible to allocate the bonus, an employer can select some other reasonable and equitable method of allocation.

If a bonus payment already accounts for the overtime premium, then no additional payment is required. For example, a bonus plan may pay, as a bonus, a 10% premium of an employee’s total compensation, including overtime premiums. In this instance, the payment already covers overtime, and no additional overtime is required.

Comp Time

Unless you are a state or local government, it is illegal to provide “comp” time in lieu of time-and-a-half for hours worked in excess of 40 in a workweek.

Federal law requires that all nonexempt employees receive an overtime premium of one-half the regular rate of pay for all hours worked in excess of 40 in a given work week. To save on wages, some employers seek to provide overtime as “comp” time to employees. In other words, instead of paying an employee time-and-a-half for overtime worked, the employee would be paid the regular straight time rate and receive an additional half-hour of paid time off to be banked and used in the future. Under the FLSA, this practice is illegal for private employers. It interferes with employees’ right to be paid their overtime premium.

For state and local governments, the FLSA has a specific provision that allows for the payment of comp time in certain circumstances, such as where it is provided for in a collective bargaining agreement or other agreement between the employer and employee.

For most employers, though, implementing a comp time program to skirt overtime obligations is a huge wage-and-hour no-no.

Pay Docking

The hallmark of the key exemptions under the FLSA is that the exempt employee must be paid a salary of at least $455 per week. An employee is paid on a salary basis when the employee receives the same amount of pay each pay period, without any deductions. For this reason, if you take deductions from an exempt employee’s weekly pay, you place their exemption at risk. This error could prove costly. The lost exemption does not only apply to the employee against whom the deduction was taken but also to all employees in the same job classification working for the same managers responsible for the deduction.20

In Orton v. Johnny’s Lunch Franchise, LLC,21 the Sixth Circuit illustrated the implications of these rules. Johnny’s Lunch employed Orton as a vice president at an annual base salary of $125,000. The employer suffered from financial difficulties and was unable to make its payroll. Thus, from August 2008 until Johnny’s Lunch laid off the entire executive staff on December 1, 2008, Orton worked without receiving any pay. The Sixth Circuit concluded that the employer’s failure to pay Orton his full salary for those four months eradicated the exemption, which, in turn, put the employer on the hook not only for Orton’s unpaid salary, but also any overtime he worked during those months.

The court started by defining the scope of an “improper deduction” from an employee’s salary: “An employer who makes improper deductions from salary shall lose the exemption if the facts demonstrate that the employer did not intend to pay employees on a salary basis.”22 The court concluded that Orton’s employment agreement (which established his annual salary) was irrelevant to the issue of whether he lost his exemption: “The question is therefore not what Orton was owed under his employment agreement; rather, the question is what compensation Orton actually received.” Because Orton did not receive his full salary for the weeks in question, he lost his exemption.

All of this begs the question—what is an employer to do if it cannot afford to pay an otherwise exempt employee his or her full salary and needs to make deductions to keep the doors open? The Sixth Circuit answered this question, too:

__________

20 29 C.F.R. § 541.603(a).

21 668 F.3d 843 (6th Cir. 2012).

22 29 C.F.R. § 541.603(a).

That is not to say a company with cash flow issues is left with no recourse. Nothing in the FLSA prevents such an employer from renegotiating in good faith a new, lower salary with one of its otherwise salaried employees. The salary-basis test does not require that the predetermined amount stay constant during the course of the employment relationship. Of course, if the predetermined salary goes below [$455 per week], the employer may be unable to satisfy the salary-level test, which explicitly addresses the amount an employee must be compensated to remain exempt.

Despite the general rule against deductions from salaries, the DOL’s rules permit employers to make deductions without risking an employee’s exemption in seven specific instances:23

1. When an exempt employee is absent from work for one or more full days for personal reasons, other than sickness or disability.

2. For absences of one or more full days occasioned by sickness or disability (including work-related accidents) if the deduction is made in accordance with a bona fide plan, policy or practice of providing compensation for loss of salary occasioned by such sickness or disability.

3. While an employer cannot make deductions from pay for absences of an exempt employee for jury duty, attendance as a witness, or temporary military leave, the employer can offset any amounts received by an employee as jury fees, witness fees, or military pay for a particular week against the salary due for that particular week.

4. For penalties imposed in good faith for infractions of safety rules of major significance.

5. For unpaid disciplinary suspensions of one or more full days imposed in good faith for infractions of workplace conduct rules imposed pursuant to a written policy applicable to all employees.

6. For any time not actually worked during the first or last week of employment.

7. For any time taken as unpaid leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act.

__________

23 29 C.F.R. § 541.602.

Other Miscellaneous Pay Issues

There are a few other pay issues to be aware of—holiday pay, vacation pay, and lactation breaks.

Holiday Pay

There is no requirement that an employer pay nonexempt employees for holidays. Paid holidays is a discretionary benefit left entirely up to you. Exempt employees, however, present a different challenge. The FLSA does not permit employers to dock the salary of an exempt employee for holidays. You can make a holiday unpaid for exempt employees, but it will jeopardize their exempt status, at least for that week. If, however, you pay the nonexempt employee a fixed salary pursuant to a fluctuating workweek calculation, you must pay the employee for any holidays off or risk the fluctuating workweek status and the overtime calculation benefits that come with it.

While not required, many employers give an employee the option of taking off another day if a holiday falls on an employee’s regular day off. This often happens when employees work compressed schedules (four 10-hour days as compared to five 8-hour days). Similarly, many employers observe a holiday on the preceding Friday or the following Monday when a holiday falls on a Saturday or Sunday when the employer is not ordinarily open.

It is also entirely up to your company’s policy whether nonexempt employees qualify for holiday pay immediately upon hire or after serving some introductory period. Similarly, an employer can choose only to provide holiday pay to full-time employees, but not part-time or temporary employees. Because holiday closings are a discretionary benefit, you can also require that employees work on a holiday. In fact, the operational needs of some businesses will require that some employees work on holidays (hospitals, for example).

You can also place conditions on the receipt of holiday pay. For example, some employers are concerned that employees will combine a paid holiday with other paid time off to create extended vacations. To guard against this situation, some companies require employees to work the day before and after a paid holiday to be eligible to receive holiday pay.

If an employer provides paid holidays, it does not have to count the paid hours as hours worked for purposes of determining whether an employee is entitled to overtime compensation. Also, an employer does not have to pay any overtime or other premium rates for holidays (although some choose to do so).

Other federal statutes, other than the FLSA, might have something to say about paid holidays.

For example, under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) you have to treat FMLA leaves of absence the same as other non-FMLA leaves. Thus, you only have to pay an employee for holidays during an unpaid FMLA leave if you have a policy of providing holiday pay for employees on other types of unpaid leaves. Similarly, if an employee reduces his or her work schedule for intermittent FMLA leave, you may proportionately reduce any holiday pay (as long as you treat other non-FMLA leaves the same).

Also, under Title VII you must reasonably accommodate an employee whose sincerely-held religious belief, practice, or observance conflicts with a work requirement, unless doing so would pose an undue hardship. One example of a reasonable accommodation is unpaid time off for a religious holiday or observance. Another is allowing an employee to use a vacation day for the observance.

Vacation Pay

Like paid holidays, there is no legal requirement to provide paid vacations to your employees. Without such a benefit, however, best of luck to you in recruiting all but the bottom-of-the-barrel employees for your business.

One issue that often arises with employees is whether they should pay for unused vacation pay at the end of employment.

The law of my home state, Ohio, considers vacation pay a deferred payment of an earned benefit. Therefore, an employer generally cannot withhold accrued vacation pay at the end of employment (just like it cannot withhold wages from a final paycheck). Unlike wages, however, because this benefit is deferred, an employer can implement a policy under which an employee forfeits unused vacation days.

Thus, a rule for vacation pay is as follows:

- If an employer does not have a policy pursuant to which unused vacation time is forfeited, and if the employee has unused, accrued vacation time, he or she is entitled to be paid for that time.

- If, however, the employer has a clear written policy, set forth in a manual, handbook, or elsewhere, providing that paid vacation time is forfeited on resignation or discharge, an employer may withhold unused vacation pay.

What does such a policy looks like? A recent Ohio appellate decision—Majecic v. Universal Devel. Mgmt. Corp.24—provided the following example:

Paid Time Off (PTO) includes sick, vacation . . . and personal time off with pay. . . . Employees will be given PTO days after one year of employment. . . . All unused PTO will be forfeited upon an employee’s resignation or termination.

Your mileage might vary, depending on the state law of your particular jurisdiction. Let me leave you with one thought, however. Notwithstanding the ability to implement a vacation pay forfeiture policy, think about whether such a policy makes for sound HR practice or whether it makes more sense to limit this policy only to “just cause” terminations, if at all.

Lactation Breaks

Section 4207 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (President Obama’s health initiative, which some call Obamacare) adds a new provision to the FLSA that requires employers to provide reasonable unpaid breaks for nursing mothers. Specifically:

- Unpaid breaks must be provided each time a lactating employee needs to express breast milk for up to 1 year after the child’s birth.

- The employer must provide the employee with a place that is shielded from view and free from intrusion from coworkers and the public, other than a bathroom.

- These requirements are mandatory for employers with 50 or more employees.

Employers with less than 50 employees are exempt upon a showing that the requirements impose an undue hardship by causing the employer significant difficulty or expense when considered in relation to the size, financial resources, nature, or structure of the employer’s business.

According to the DOL’s published, preliminary interpretation of section 4207,25 this provision imposes some significant requirements on businesses.

__________

24 2011-Ohio-3752, 2011 Ohio App. LEXIS 3177 (Ohio Ct. App. Jul. 29, 2011).

25 Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division, “Reasonable Break Time for Nursing Mothers,” http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/2010/pdf/2010-31959.pdf, December 21, 2010.

Paid or unpaid breaks? Employers are not required to compensate nursing mothers for breaks taken for the purpose of expressing milk. However, lactation breaks are covered by the same rules that govern other workday breaks. If the employer permits short breaks, usually 20 minutes or less, the time must be counted as hours worked and paid accordingly. Additional time used beyond the authorized paid break time could be uncompensated.

What is a reasonable break time? Employers should consider both the frequency and number of breaks a nursing mother might need and the length of time she will need to express breast milk. The DOL believes that most women will need to take two to three breaks per each eight-hour shift, each break lasting between 15 and 20 minutes. These guidelines, however, are just that, and will vary from woman to woman depending on specific circumstances and needs.

What is an appropriate lactation space? An employer has no obligation to maintain a permanent, dedicated space for nursing mothers. Any space temporarily created or converted into a space for expressing milk or made available when needed by a nursing mother is sufficient, provided that the space is shielded from view, free from intrusion from coworkers and the public, and suitable for lactation. The only room that is not appropriate is a bathroom. The DOL also believes that an employee’s right to express milk includes the ability to safely store the milk.

What qualifies as an undue hardship for employers with less than 50 employees? The difficulty or expense must be “significant,” which is a stringent standard that employers will only be able to meet in limited circumstances.

Is there a relationship between lactation breaks and the FMLA? The DOL does not believe that breaks to express breast milk can be considered FMLA leave or counted against an employee’s FMLA leave entitlement.

All of these rules, regulations, and cases beg the following question—is workplace lactation a problem that needs a solution? Consider the following statistic. Since Obamacare mandated that employers provide space in the workplace for mothers to lactate, the DOL has cited a whopping 23 companies for not providing adequate lactation breaks or spaces.26

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s latest statistics27, there are 5,767,306 American employers and yet only 23 have been cited for a violation of this mandate. In other words, the DOL has cited 0.0004% of all American employers. If we only consider employers with 20 or more employees, the DOL has cited 0.0038%—still an infinitesimally small number. If we only consider the largest of employers—those with 100 or more employees—the percentage of citations drops to a still-miniscule 0.023%.

__________

26 Alicia Ciccone, “Breastfeeding Law Poses Unique Challenge to Businesses,” http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/01/05/breastfeeding-law-poses-challenge-to-businesses_n_1186982.html?ref=business&ir=Business, January 5, 2012.

27 United States Census Bureau, “Statistics of U.S. Businesses,” http://www.census.gov/econ/susb/.

What do these numbers mean? Either that the lactation mandate is not yet widely known, and as public knowledge catches up with the law’s requirements complaints (and citations) will rise. Or the lack of lactation space in American workplaces is a myth that does not need a legislative solution.

Moreover, we already have laws that handle this issue. Under Title VII and its state counterparts, gender discrimination is illegal. The last I checked, women are the only gender that can lactate. For this reason, unless you are going to deny all employees the ability to take short breaks during the workday for any reason (e.g., smoking, bathroom, a cup of coffee), denying women the ability to take a similar short break to lactate is gender discrimination.28

What is the best practice for employers with fewer than 50 employees and therefore exempt from Section 4207? Before a company institutes a policy that prohibits breast pumping or breast-feeding at work or terminates a lactating employee for taking breaks, it must consider how it has treated other employees’ breaks during the workday. If you cannot find a consistent pattern of discipline or termination of similar nonlactating employees, you must reconsider the decision. A no-breast-feeding policy will, by its very nature, only apply to women. What other similar policies might a company have? Does it allow bathroom breaks during the workday? Smoke breaks? Other personal time? If so, a ban on nursing during the workday should be deemed discriminatory on its face, because it is necessarily targeted only at women.

What Is the Answer? Audit, Audit, Audit

The sweatshops of the Great Depression that led to the passage of the FLSA and its 40-hour workweek are virtually nonexistent in today’s America. Nonetheless, claims for unpaid overtime continue to rise, more than doubling in the federal courts in the last decade. These cases rarely are the result of the intentional withholding of overtime premiums. Yet, as I’ve illustrated, the complexity of these rules renders compliance difficult, if not impossible.

__________

28 At least one court disagrees. In EEOC v. Houston Funding, Case No. H-11-2442, 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 13644 (S.D. Tex. Feb. 2, 2012), the court concluded that “[f]iring someone because of lactation or breast-pumping is not sex discrimination,” because once the employee gave birth, she was no longer pregnant and her “pregnancy-related conditions” covered by Title VII ended.

Thus, the question is not whether companies need to audit their workforces for wage-and-hour compliance, but whether they properly prioritize doing so before someone calls them on it. You cannot predict when, why, or who the DOL will audit or which employees will sue you. What can you do? Take a detailed look at all of your wage-and-hour practices: employee classifications, meal and rest breaks, and off-the-clock issues. Make sure you are 100% compliant with all state and federal wage-and-hour laws. If you are not sure, bring in an attorney who knows these issues to check for you.

If you are ever investigated by the DOL or sued in a wage-and-hour case, it will be the best money your business has ever spent. It is immeasurably less expensive to get out in front of a potential problem and audit on the front end instead of settling an expensive and time-consuming class action claim on the back end. The time for companies to get their hands around these confusing issues is now and not when employees or their representatives start asking the difficult questions about how employees are classified and who is paid what.

Concluding Thoughts—A Glimmer of Hope from the Supreme Court?

A little more than three months after the DOL issued its opinion on mortgage loan officers, the Second Circuit, in In re Novartis Wage and Hour Litigation,29 reached the same conclusion regarding another group of employees traditionally believed to be exempt administrative employees—pharmaceutical sales representatives. The court in the Novartis case concluded that the sales reps did not qualify for the administrative exemption because their jobs lacked any exercise of discretion and independent judgment. Specifically, the court pointed to the reps’ lack of any role in planning marketing strategies or formulating the core messages delivered to doctors, their inability to deviate from the promotional core messages or to answer any questions for which they have not been scripted, and quotas for doctors’ visits, sales pitches, and promotional events.

In the wake of Novartis, the courts are split on this issue. In Christopher v. SmithKline Beecham Corp.30, the Ninth Circuit agreed that sales reps are not exempt. But, in Schaefer-LaRose v. Eli Lilly & Co.31, the Seventh Circuit disagreed. This issue is currently on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, which will decide two issues: 1) whether deference is owed to the DOL’s interpretation of the exemption and related regulations and 2) whether the exemption applies to pharmaceutical sales representatives at all.

__________

29 611 F.3d 141 (2nd Cir. 2010).

30 635 F. 3d 383 (9th Cir. 2011).

31 Case No. 2012 U.S. App. LEXIS 9300 (7th Cir. May 8, 2012)

On June 18, 2012, the United States Supreme Court issued its long-awaited opinion in Christopher v. SmithKline Beecham Corp.32 The Supreme Court, by a 5-4 margin, held that pharmaceutical sales representatives are exempt, outside salespeople to whom employers need not pay overtime.

In summary, the Court concluded the following:

1. To be considered a salesperson, one need to actually consummate a transaction. It is sufficient that the promotional work performed by the employee can lead to a sale. This rationale rebukes the argument of the DOL, which the Court called “quite unpersuasive” and lacking the hallmarks of thorough consid-eration.”33

2. Nonbinding commitments from physicians to prescribe certain drugs qualify as sales under the FLSA’s outside sales exemption. This rationale applies a common-sense approach to a statute that is often confusing and too rigidly applied.34

The following is the million-dollar quote from the Court:

Our holding also comports with the apparent purpose of the FLSA’s exemption for outside salesmen. The exemption is premised on the belief that exempt employees “typically earned salaries well above the minimum wage” and enjoyed other benefits that “set them apart from the nonexempt workers entitled to overtime pay.” . . . It was also thought that exempt employees performed a kind of work that “was difficult to standardize to any time frame and could not be easily spread to other workers after 40 hours in a week, making compliance with the overtime provisions difficult and generally precluding the potential job expansion intended by the FLSA’s time-and-a-half overtime premium.” . . . Petitioners—each of whom earned an average of more than $70,000 per year and spent between 10 and 20 hours outside normal business hours each week performing work related to his as signed portfolio of drugs in his assigned sales territory—are hardly the kind of employees that the FLSA was intended to protect. And it would be challenging, to say the least, for pharmaceutical companies to compensate detailers for overtime going forward without significantly changing the nature of that position.35

__________

32 567 US __, 132 S. Ct. 2156, 183 L. Ed. 2d 153 (2012).

33 Id. at 2169.

34 Id.

35 Id. at 2173.

I have long argued that the FLSA is an anachronistic maze of rules and regulations that does not fit well within the realities of the 21st century workplace. It seems that at least five members of the Supreme Court are inclined to agree with me. This excerpt provides hope for businesses that in the face of an overly active DOL and an overly confusing statute, courts can provide relief by adopting common sense interpretations to these dizzying rules.