PRINCIPLE 14

Be a Mensch

First things first: Let’s deal with the chapter title. Although it sounds like a place for guys to sit while the women they know shop for clothes—that is, the man’s bench, or mensch—this isn’t what the word means. In Yiddish, it means “a good person,” someone who has qualities you would hope for in a close friend or colleague.

This is how you should behave in business. You should be a mensch.

I suppose that comment isn’t surprising coming from someone who once thought he would become a rabbi. I realized early on that you cannot follow one set of rules while reading the Torah—the Bible—and another as you live the rest of your life. You either practice what you believe in, or you don’t.

It’s a lesson I learned growing up watching my dad, Abram Green. A&P was his largest customer and one day, during a period when his business was struggling, A&P paid Dad twice by mistake. A&P sent Dad a check for $35,000, paying for goods that it had previously paid for.

Some of Dad’s employees told him to keep the money. “They are a big company,” they said, “They’ll never miss it.”

“It isn’t about them,” Dad said as he returned the check, “It’s about me.”

I think that’s a good place to begin the discussion, with you and what you believe. What are you totally comfortable doing in your interactions with others? How do you want to live your business life when it comes to morals, ethics, and doing the right thing? Do you want to be a mensch?

When I ask this, people instantly respond, “You don’t understand. If I always do what you say, I’m going be exploited. Not everyone thinks this way, and they’ll take advantage of me.”

When they say this, I tell them I understand completely. I then explain to them what happened to me back when I attended Rutgers University. I never had a car, but I was getting serious about my then girlfriend, Lois (Lois Green, my wife of fifty-plus years), and I finally decided that I was going to get a car. One of my fraternity brothers sold me a car he had refurbished. The first time I took it out, Lois and I had not gone more than two blocks when the engine literally fell out.

When I confronted my fraternity brother, all he said was, “Welcome to the real world, Lenny Green.”

So I understand that people may try to take advantage of you, but you can choose whether or not you take advantage of them. I know I can only control certain things, but I have chosen not to take advantage of others. This is a lesson I try to get across every year in class.

Each year, I give a hypothetical problem that involves the students having to make an ethical decision on whether they want to cheat to be successful or whether they will remain ethical. Every year the majority decides to be ethical.

Then, unbeknownst to them I give them a real-world problem.

Earlier in the semester, I asked Woody Lappen, the man who for twenty-five years has run one of the concessions on the Babson campus, to come in and talk about his business. (Woody is a classic entrepreneur.)

A couple of weeks later, Woody walks into my classroom and interrupts the class.

“I am sorry, Professor,” Woody says. “Would you mind terribly if I leave these fifty slushies at the back of the room? There is a faculty meeting here right after your class, and I want to surprise the professors.”

I tell him it wasn’t a problem and return to teaching my class. About ten minutes later, I walk over to the slushies and say, “These sure look good. I’m not going to the faculty meeting—in fact, the meeting is for another department entirely—but he did say the slushies were a surprise. The professors will never know if I have one, so I think I will.”

I take a sip and say, “Gee, these really are great. Does anybody else want to have one?” A couple of the students raise their hands, and I give one to each of them. They, too, rave about the drinks and a few more students ask for one, and then a few more, and before you know it, all the slushies are gone.

Just before the class ends, I ask the students if they think what we did—drinking all the slushies—was wrong. We get into a debate about whether or not it was, and then I reveal something that you might have guessed.

“I asked Woody to bring the slushies into class. I paid for them. They weren’t a surprise for the teachers. There is no faculty meeting. This was a test to see what you would do when faced with a real situation, not a hypothetical case study. I wanted to reinforce the lesson of ethical business behavior that we talked about before.”

This triggers another round of discussion with many of the students saying that on their own they wouldn’t have taken a slushie, but once they saw me do it, they figured it was okay.

This brings up a couple of points. First, it really shouldn’t matter what anyone else does; you are ultimately responsible for deciding between right and wrong for yourself. You want to be able to face the person staring back in the mirror.

Secondly, saying that is a bit naïve on my part. Of course people are going to watch what the leader—me in this case—does. His actions always speak far louder than his words. The head person sets the tone for everything in a company, and people can easily justify dishonest behavior by saying, in this case, “If Len did it, it is okay.” People can rationalize anything.

What that means is if you’re the leader, you need to model the behavior you want from your employees. This modeling extends to showing the rest of the organization how you’re going to treat employees who are unethical. In my case, I fire them. We have a zero tolerance policy in this regard in my company.

I know, many think this is an overreaction. They tell me that the punishment should fit the crime. If you fudge your time sheets (put in for a few more hours than you actually worked), I should just make you repay the money; and if you ever do it again, then you’re fired. Alternatively, I could also have you contribute an amount equal to what you overstated to charity. That way, you have to repay twice what you took.

These alternatives have merit, but that isn’t the approach I have chosen to take. I don’t think there are a lot of shades of gray. If you cheat a customer or our company, you are fired. If your supervisor knew, or should have known about it, he or she is fired too.

You’re trying to create a certain culture. You want everyone in your organization to know what you and your firm stand for. Firing people does that. So does giving people paid time off to volunteer for community or charitable projects and “encouraging” people to give back.

HOW YOU SHOULD DEAL WITH OTHERS

Now, just because you’re always trying to do the right thing—and are making sure that your people do the right thing as well—it doesn’t mean you need to tie one hand behind your back when you’re negotiating with others. For example, it’s more than fair to put yourself and your product or service in the best possible light.

I’m also a big believer in how the late Roger Fisher, the Harvard professor who wrote the best-selling book on negotiation, Getting to Yes, says you should handle a business transaction. He advocates always being honest and answering forthrightly every question put to you. He also says you need not do more than that. If someone doesn’t ask you about something, you don’t have to tell that person. If there’s a flaw in her reasoning—she’s undervaluing something that you know should sell for far more, for example—you don’t need to point it out.

However, I probably will if it’s someone I have an ongoing relationship with. I’ll want to be fair and hope my approach is reciprocated. I go into every business transaction wanting to believe the person I’m dealing with will be honest and aboveboard. However, I’m always prepared for them not to be.

Shame on me if I believe everyone is going to be honest—but I would like to start there.

A quick story will make the point. Early in my career, I did a lot of sale-leasebacks of shopping centers. The owners of the entire shopping centers or the anchor store, looking to cash out on their investment, would sell the property to me, and, as part of the deal, they would agree to rent the property back from me at a fixed price for a number of years. (This guaranteed a return on the money I put up.)

Well, the owner in a particular shopping center said he was willing to sell at substantially below market rates because he was strapped for cash.

“That’s the only reason?” I asked.

“Yes.”

Now, admitting you’re in a bad financial position during negotiations is never a good ploy (unless you’re being disingenuous). So I decided to dig a little deeper. I had visited the shopping center previously on numerous occasions and knew it was located on a busy highway. The foot traffic appeared to be what the owner said it was, and the existing leases of the other stores in the shopping center were just as represented. Just to make sure I wasn’t missing anything, I hired a helicopter so we could literally get a birds’-eye view of the surrounding area. Sure enough, we spotted a problem almost immediately. The state was building a new highway that would siphon off a significant portion of the traffic that went by the center.

We were still scheduled to close on the deal, and I showed up at the appointed hour.

“You know, I was thinking about your financial position,” I began. “I hate to take advantage of someone when he’s down. I’d like to raise my offer to what the property is actually worth.”

“If you want to pay more, I’m certainly not going to object,” the seller said.

“I didn’t think you would,” I said, “but before I do, look me in the eye and tell me there are no problems you haven’t disclosed.”

“There aren’t,” he said, staring right at me.

“So you don’t think the fact that a new highway is being built and that it’s going to reroute 80% of the traffic is a problem?”

Trust, but verify.

The seller didn’t say a word. He just gathered up his papers and left the room. That was the end of the deal—and our relationship.

Was I surprised he was trying to pull “a fast one”? No. Some people are just wired that way. Why do people do things like this? It could be because of the Maslow hierarchy and they need to make the deal happen to survive, or it could be that they think that business is a game without any rules, so they believe they have to be cutthroat at all times. Or it could be that they simply have to win at all costs.

When I go into a deal, I’m always expecting that the other person will do something (unethical) that I wouldn’t do.

Their motivation doesn’t matter. You just need to guard against their actions. For reinforcement of this principle, you should read a few accounts of how Bernie Madoff defrauded friends, relatives, charities, and countless others.

THE BENEFITS OF BEING GOOD

Can I say, with absolute certainty, that there are tangible financial payoffs from what I am advocating? No, I can’t quantify the numbers. Am I convinced that it has contributed to my success? Yes.

It isn’t hard to explain why.

For many years I’ve done real estate deals with someone, and all he required was a handshake. The legal work followed thereafter, and the legal documents were exactly as the deal had been described it would be. The man, Larry Kadish, is one of the most successful real estate people I have ever met.

However, there was one deal, unbeknownst to Larry, where the tenant, who leased the entire building, went bankrupt just as we closed. As a result, I owned a building with no tenant. I had a real problem, because the value of a property without a tenant was far less than that of a property with a Triple A–rated tenant—which is what I had originally purchased. Larry had no legal obligation to do anything, but he voluntarily substituted a property of equal value.

You can see why Larry and I have been doing business together for over thirty years.

If you have a good working relationship with someone whom you know to be honest and a problem comes up, it’ll be fairly easy to resolve. Your supplier says he forgot to charge for part of an order. You can spend ten seconds checking that you haven’t been previously billed and then write the check. There is no searching for hidden motives.

If you have trust in one another, you can count on the other person to do the right thing.

CASE STUDY: THE EXOTIC JUICE COMPANY

While the baby-food market is typically dominated by large companies, starting in the 1990s a number of new entrants who emphasized quality products entered the field.

The Exotic Juice Company was founded in the late 1990s, and its goal was to be the number one quality baby-food juice drink. It used 100% juice, and its president, the company’s spokesman, was dubbed by the press “Mr. Natural” since the only ingredient in Exotic Juice was “100% natural juice. No additives, no colorings, just juice,” a fact the president said every chance he got when interviewed on radio and TV. Being 100% juice, he said, accounted for the product’s superior taste.

Sales started strong and steadily increased in the company’s first four years. However, since there were no barriers to entry, pretty soon Exotic Juice found competitors everywhere it looked.

All of a sudden, Exotic Juice started losing money, a lot of money. A quick look at the cost to produce a bottle of juice shows why this was the case:

Selling price because of competition |

$1.00 |

Breakdown of Items |

Costs |

100% juice |

$0.60 |

State-of-the-art bottle/packaging |

.05 |

Factory overhead |

.25 |

Marketing and research |

.20 |

SG&A |

.15 |

Total cost |

$1.25 |

Loss per bottle |

(.25) |

If the company didn’t do something, it would go out of business.

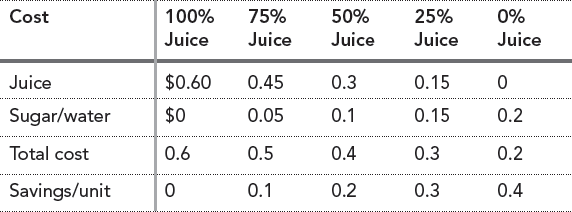

Since the juice was the most expensive component, one suggestion was for the company to reduce the juice content and substitute water and sugar. If it used different percentages of juice, the profit would rise substantially, as reflected below. The taste with the extra sugar was found to be sweeter and more appealing. Competitors were using only a percentage of juice in their similar products.

Note 1: A reduction of 50% of the juice content resulted in a $0.05 profit per bottle.

Note 2: A reduction of 99% of the juice content resulted in a profit of approximately $0.34 a bottle.

EXERCISE 13: JUICE

1. Would you reduce the juice content? Zero juice would increase profits by millions of dollars.

2. Would you show the percentage of juice on the label?

3. Would you use “new and improved” on the label?

4. Would you use other strategies to re-invent the company?

FOUR TAKEAWAYS FROM THIS CHAPTER

1. Create a personal mission statement. Just as you have an overall strategy and mission statement for your company, you need to have one for yourself.

2. Follow the Golden Rule. It sounds simplistic, but it’s still a good rule of thumb: In the long run, do you want people to treat you the way you treat them?

3. Remember, cheating isn’t winning. Yes, you want to win, but you want to win the right way.

4. Understand that ultimately, only you are responsible for your behavior. You don’t get to rationalize it away by saying, “Everyone does it this way,” or, “It was okay with my boss.” You decide wheter you’re going to be a mensch, or you’re not.