Chapter 7

Don’t Forget the Story

People of all ages and backgrounds are drawn to stories because they not only convey ideas, but they connect those ideas and put them in a meaningful context. They are much more than just an assemblage of disconnected information. While reporters bring audiences facts, storytellers let audiences know how those facts are relevant to their own lives and why they should care. With rare exception for short breaking news updates and spot news, today’s entrepreneurial journalists are charged with providing a more meaningful service to their audiences than simply delivering facts. Facts alone are only part of the story. It takes a skilled and thoughtful journalist to tell the story behind those facts, those data points or those trends.

Basic human stories cross cultures and time. They’ve been passed down from the earliest humans to today, carrying living traces of those who have informed them and shaped them along the way since the very beginning. Stories are universal. Like each day and each lifetime, they have beginnings, middles, and ends. They are the basis of mythology, the way people have tried to understand the world and their place in it since the dawn of humanity. They respond to humanity’s universal unanswered questions through the ages, although the questions have evolved somewhat from “What makes the sun rise each morning in the east and fall each evening in the west?” to “What is the meaning of life?” or “Why am I here?”

The human desire to understand the world is remarkably similar in both the realm of fiction storytelling and nonfiction news reporting. Although it may sound odd or opposed to the journalistic ideals of objectivity and accuracy, understanding the central role storytelling plays in our daily lives can help all kinds of journalists forge deeper and more meaningful connections with their audiences. Most of us are familiar with how the human hunger for stories led to the earliest dramas staged by the ancients, many of them depicting the mythic world. To this day, our hunger for stories keeps us watching movies, TV shows, and plays. People are naturally interested in others’ stories. This makes the journalist’s job easy—as long as he’s able to think like a storyteller.

Figure 7.1 Ernest Hemingway applied the storytelling skills he had acquired as a journalist to his spare, tightly written novels. Photo by Lloyd Arnold.

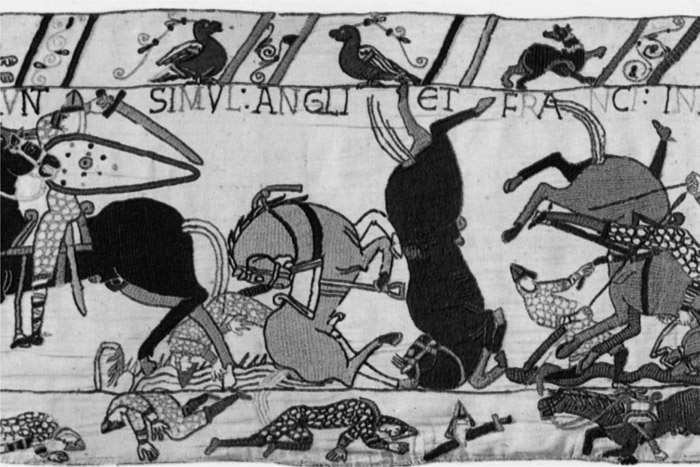

Figure 7.2 The 230-foot Bayeux Tapestry told the story of the Norman Conquest in the first century of the last millennium. It was likely commissioned to help the French make sense of the violent events that led to the Battle of Hastings.

Figure 7.3 Cpl. Anthony Gomez (left) and Pfc. Roy Heggernes meet with children in Kandahar province in an official U.S. Army photo. Images like this help tell the story of the American involvement in Afghanistan while humanizing U.S. soldiers. Photo by Sgt. Breanne Pye.

The Human Angle

Stories involve people. Readers respond to stories they can relate to. That’s why editors sometimes ask writers to “put a human face” on an issue. Let’s say a reporter is deep into researching a story about how new health care laws will affect people in her community. The reporter goes to her editor with the basic facts of the story: Low-income families will have to spend a larger percentage of their income on health insurance, they may have to change primary care doctors, and some general practitioners may leave the community.

The editor may try to put herself in the mindset of the story’s target audience. She might say to the reporter, “This all sounds like it could be bad for me, but I’m already working two jobs. I’m not motivated enough to spend my limited free time reading this story.”

How does the reporter make the story—that is already relevant to the target audience—more readable? Actually telling a story will help. No matter how relevant a topic may be to a particular audience, reading a dry analysis is like homework. Most people won’t do it unless it’s required. But everyone likes a good story. So the reporter’s challenge is determining how to convey what may ordinarily be dry facts in a way that entertains and engages. This is almost impossible to do without including people.

Instead of simply reporting on changes to health care policy, the journalist finds a family in her community that will be deeply affected by the changes. For a long-form story, the journalist may visit the family several times to document a complicated morning routine:

Nancy, a single mother who works two full-time jobs to support her two kids, gets up at 4 a.m. each day to bathe her youngest child, who is developmentally disabled, and get her ready for the day program she attends for sixteen hours each weekday when she is at work. She then must feed and dress both of her daughters, then ride the bus with them to different stops on the way to her first job of the day. It’s a punishing schedule that’s about to get worse when changes in her health care coverage mean that she will no longer be able to afford to send her youngest daughter to the day program while she is at work.

Instead of simply asking the reader to imagine how tough life will get for some people already on the edge, a skilled reporter will bring the story of this new legislation’s impact directly to her audiences and make it real. Instead of simply explaining that cutbacks will mean less money for daycare and skilled nursing programs, the reporter can show the real human impact on those directly affected by the changes. While richly detailed writing could help bring this story to life, a reader would also want to see photos of the family. It is difficult for readers to ignore a photo in which subjects with worried or worn-looking faces make eye contact from the page or the screen. An image brings an emotional impact text alone cannot produce. This is the same reason why child welfare organizations that ask for donations advertise their services using pictures of children with dirty faces or clothes—and why animal rescue organizations run commercials on late-night TV showing injured or suffering animals. While a statement or plea may be easily ignored, it is nearly impossible to ignore a photo or a video of an animal with exposed ribs or visible sores.

The online version of Nancy’s story would be much more compelling with a video or two, depending on the length of the main story or the text. The editor may want a short video showing Nancy’s grueling morning routine. Shots could include a close-up of Nancy’s alarm clock as it registers 4 a.m., followed by a close shot of Nancy’s tired face as she rubs the sleep from her eyes. These images would show Nancy’s fatigue in a way no amount of text can. (Remember your old English teacher’s admonition to “show, don’t tell”? Video makes that easier than ever.) The editor may then want to see several quick clips of Nancy rushing to get her children ready for the day. She may want to see additional shots that suggest Nancy’s frustration and the challenges she faces before she even leaves her apartment in the morning. Maybe her daughters are fighting, and one starts crying. Maybe she drops the oatmeal while rushing across the room. Maybe the dog starts barking, raising stress levels for everyone. It takes just a few seconds of this kind of footage to paint a clear and compelling picture.

Another video later in the story could show Nancy as a loving mother, hugging her children as they drift off to sleep. Or it could show Nancy, in a short interview clip, crying and wondering aloud whether she’ll be able to manage when the new health care changes are enacted. While there are several other important aspects of the story that will be included in its text, such as side-bars or information graphics explaining the relevant changes to the law, an information-heavy story like this would be unlikely to attract much reader-ship without the human element.

Ask the Right Questions

Effective interviews are the cornerstone of compelling feature stories, particularly profiles. Regardless of whether they will be shared with audiences directly via video or audio or contextualized by a journalist taking notes, interviews get to the heart of a story’s key questions. The information sources provide is only as compelling as the interviewer is skilled because it’s more than just the questions themselves that journalists must concern themselves with. It’s also how and when to ask, and knowing how to conceive good follow-up questions on the fly.

In addition to excellent oral and written communication skills, journalists must be interested and engaged in the interview if it is to yield any compelling quotes. Attitude is everything, and interview subjects can pick up subtle cues from the journalist that may make them more timid or less likely to open up and provide the kind of sensitive or personal detail that makes for great stories. If a journalist expects to get good quotes from an interview subject, he must be as genuinely interested in the subject as he expects his readers or viewers to be.

Because we all spend much of our lives speaking with the people all around us, most of us tend to think we are reasonably skilled interviewers. After all, some people may ask themselves, how hard could it be to talk with someone? As it turns out, conducting effective interviews isn’t quite so straightforward or intuitive. First of all, it is important to keep in mind, conducting an interview is more than just talking with someone. Consider that most conversations are two-way interactions. Although some prominent journalists are known for making themselves central to any interview they conduct, for the rest of us, the focus must be on the subject.

Anyone who has received even the most basic journalism training knows that journalists report the story without becoming part of the story. The same rule applies to interviews. Although it can be difficult for a journalist to resist the urge to insert himself into the conversation, a true pro knows that the focus must remain on the subject. This means that the journalist needs to listen and let the subject complete his thoughts before asking the next question. Even if the journalist disagrees with what the subject is saying or has conflicting or contradictory information to share, that information should be based in fact and not the journalist’s personal observation. That doesn’t mean that the journalist shouldn’t question or challenge a point or assertion when the subject says something that differs dramatically from the viewpoints of a significant share of the audience. But it does mean that a journalist should base his questions on what his audience would like to know rather than what he would personally like to challenge or question.

Trained journalists and probably others can easily recognize when a journalist inappropriately inserts himself into a story by adding personal anecdotes or other information that is relevant only to him. This not only wastes time for the subject and the audience, but it rings of amateurism and lack of professionalism that can damage the journalist’s reputation. Sometimes a journalist will add something to prove knowledge in a particular area. Other times a journalist will not say something to avoid looking ignorant. This is not a good strategy. Often people worry about revealing themselves as ignorant on a particular subject. It is essential that the reporter adequately prepares for an interview by learning key ideas and biographical details about the subject. However, it is just as essential that the reporter puts himself in the position of an audience member and asks the subject to define terms, acronyms, and other words and phrases not in common usage. Even if the reporter knows what these words and terms mean, his audience may not. The reporter should not be concerned about looking stupid. The best, most respected interviewers everywhere use this technique without any loss of respect or prestige. It is the sign of a true professional who is more concerned about his audience’s welfare than about looking smart. (A journalist who goes out of his way to show that he knows something actually only winds up looking incompetent.) Like all other effective interviewing techniques, being a better listener becomes second nature after a while. Journalists can expect that improving their listening skills on the job will also make them better listeners at home.

Al Tompkins, senior faculty for broadcast and online at the Poynter Institute for Media Studies in St. Petersburg, FL, is a veteran journalist and one of the top journalism trainers in the United States. Tompkins wrote the book Aim for the Heart: Write, Shoot, Report and Produce for TV and Media, which serves as a bible for many multimedia journalism professors and their students. In Aim for the Heart, Tompkins wrote that the most important part of reporting is listening. Indeed, he continued, “Listening is the essence of journalism.”1

It takes some work for most of us to become better listeners because most people could stand to work on their listening skills in daily life. Among the bad listening habits most people have, Tompkins wrote, are lack of interest, judgment or bias that could lead to a lack of attention or respect. Journalists often interview people with ideas and mindsets that are different—often radically different—from their own. Like any true professional, even on hearing something he finds highly offensive, the interviewer must not let the words or ideas derail the interview. Above all else, he must not involve himself in the discussion or get drawn into a debate on the topic. Occasionally an interview subject will challenge a reporter to weigh in or cast judgment on an idea. Regardless of his personal beliefs, he must at least maintain the appearance of neutrality and let the subject know that the code of journalistic professionalism prevents him from becoming personally involved in the discussion.

Ask the Right Questions in the Right Way

Not all interviews are conducted under ideal circumstances. Reporters know they will not always get the time they think they need to meet a story’s demands. But entrepreneurial journalists in particular are flexible and able to adjust their plans as needed. If they can schedule a sit-down interview with a subject, seldom do they get all the time they want. Alternatively, they can conduct interviews by phone, Skype or other means. And sometimes, because of scheduling or a subject’s unwillingness to talk, the journalist may have to catch him between meetings or events. Regardless of the time or circumstances, a skilled journalist is prepared with broad, thoughtful, open-ended questions that may take the subject some time to respond to, as well as short, quick, to-the-point questions that may put the subject on the spot or make him look guilty if he is avoiding the media. In this kind of unplanned situation, an entrepreneurial journalist needs to have various tools available to record the subject’s comments for sound bites or short video clips, or even for longer interviews if there is a last-second opportunity to conduct one.

The appropriate choice of media depends on several things, some of which can be anticipated and planned for in advance. If the subject is actively trying to avoid the media, video is the best tool to reveal his behavior and personality. Because it gives a more complete picture of the subject’s appearance, voice, and behavior, it provides the most information with which the audience can reach their own conclusions. For situations like this, a reporter might want to have a portable video camera and microphone of reasonable quality (on a smartphone or other mobile device, if necessary) and higher-quality equipment (including a tripod) if the opportunity to hold a sit-down interview arises.

Elements of Effective Storytelling

Tease the story

Stories can be told in all media and through all combinations of media. Anything that is more than just a fact or collection of facts can be a story. Even a tweet can be a story if the writer is skilled at compression. Let’s say that while reporting a story, a writer shot a portrait of the subject in which he has a curious or revealing expression on his face. The reporter could tweet the photo along with a link to the story online and the comment: “Who is Mr. Wonderful?” Of course it’s not a complete story. It’s just a tease for the full story—which is exactly what’s expected on a microblogging platform. But instead of simply tweeting just the link or the photo, adding an attention-getting line helped start the story for the reader, who may be compelled to find out why this widely smiling man is Mr. Wonderful, and why she should care.

Start strong

From your early literature classes, you may remember having discussed the type of conflict in a story. Common conflicts included “man vs. man,” “man vs. nature,” and “man vs. himself.” Although the centrality of conflict to storytelling may not have been clear to you as a young person, all you need to do to understand the statement that all stories involve some kind of conflict is read a story that is utterly without conflict. If you have read such a story, you probably don’t remember it, because stories without conflict tend not to be very memorable. Stories without conflict lack a main point. No journalist wants to write pointless stories.

What’s important to remember about conflict in stories is that it usually dictates the overall structure of the story. Although the pacing in a news story is generally much different from the pacing in a work of fiction, some elements are remarkably the same. Just like a good fiction story or movie, a good news story begins with a hook—or a lead—that graphically or dramatically presents the problem or question. Just like the opening scene of a movie, the beginning of a news story needs to hook the audience and keep them reading and wanting more. It is highly advisable to start with a powerful scene that illustrates the main conflict or question while creating suspense. The scene itself may prompt questions that will motivate the reader or viewer to stay tuned for the answers.

It is dusk. A constant drizzle has left the streets wet. A police car, its siren on, speeds by. A teen boy lies crumpled in the street, his tan pants marred by tire tracks. Why did the police car rush away from the scene? Whether it’s a movie or a news story, the audience wants to know. This will keep them watching or reading.

Of course not all stories must start dramatically in order to entice audiences. Smaller stories can be just as compelling—although they tend to work better in journalism than in mainstream movies, where subtlety tends to be a hard sell. As a journalist creating a feature, you can find powerful ways to tell human stories through small, rich details. You may describe or show, for example:

- A family sitting down to dinner, one place set but empty.

- Question raised: Who is missing and why?

- A middle-aged man packing small items from his work cubicle into a box.

- Questions raised: Where is this man going? Was he fired?

- A woman with a large backpack hugging a small boy and crying.

- Questions raised: Where is she going? Is she leaving her son?

Be guided by questions

Sure, you won’t know your exact thesis when you first set out to research your story, but you should at least have some idea of what you’re expecting to find. In the early phase of your research, a general idea or broad question is enough. But you should have at least some sense of where you’d like to go with the story before you start conducting interviews. After all, your subjects want to know what the story is about before they sit down for an interview. Tell them your general direction but don’t be too specific until you’ve conducted enough research and interviews to have a working thesis to guide you. But the real value of a working thesis is in guiding your research and saving you the time of investigating false leads or pursuing other avenues of research that will not be relevant to your story.

Let content dictate structure

We’ve already established the importance of conflict. The nature and timing of that conflict will go a long way toward determining the appropriate structure for the story. If the conflict itself is dramatic enough to open your story, you will need to orient the audience as soon as possible after the dramatic opening scene. A cinematic structure is one common way to structure a story with a dramatic climax. It looks like this:

- Dramatic opening scene.

- “Nut graf” or informational paragraph explaining the basic facts needed to understand the opening scene while preparing the audience for the journey to come.

- Chronological description of events leading to the opening scene (the actual beginning of the story).

Not all engaging narratives need a dramatic opening scene. Less dramatic stories or stories without a major climax such as a shooting, a robbery or the birth of a child will likely follow a different structure. Because the reporter wants to ensure the story is relatable to his audience, he may want to open with a universal situation or a familiar question. For example, a story may begin with a familiar question: “Does my vote really count?” or “Should I give money to panhandlers?”

The question itself doesn’t require much explanation, but the audience will want to see examples of other people like them who have been plagued by similar thoughts. They will enjoy trying to get their own questions answered by those in the story to whom they can relate. This kind of story will likely build more slowly. Although there is a conflict, it is more subtle and internal. It may not be particularly cinematic.

Regardless of the nature of the conflict, there is a classic structure familiar to most people from all kinds of storytelling, including television and film. It is often quite formulaic, but the formula exists for a reason: It works. Think about the following formula the next time you watch an hour-long television drama:

- Scene setting and establishing characters.

- Rising tensions as the story ramps up toward its central conflict.

- The crisis point.

- Resolution of the crisis.

- Conclusions and lessons learned.

Although television audiences and writers have become more sophisticated in recent decades, back in the 1970s and 1980s, the classic storytelling structure was in clear evidence. Fantasy Island, a relic of classic 1970s TV, was perhaps most direct in its embrace of traditional narrative technique. At the beginning of the show (Act 1), guests would arrive on the island and explain the nature of the fantasy they would like to live out on their visit. In the middle section (Act 2), which lasted about half the show, the guest would have their fantasy, only to realize—at the crisis point—that they didn’t really want what they thought they wanted or that they already had everything they needed in daily life. Then in the final ten or fifteen minutes of the show (Act 3), the guests would reveal that they had learned and grown from the experience of their failed fantasy and would be better people for it. This is the classic three-act play structure, consisting of the establishment of story and character rising to a point of conflict, then a turn or transformation, followed by resolution, which is often—but not always—satisfying. As audiences have grown more sophisticated and aware of the classic three-act structure, they have become open to new variations, among them the inconclusive ending (which has itself become an action film cliché, alerting viewers to the likelihood of a sequel).

Applying narrative structure to journalism is now a decades-old concept, yet for some journalists—particularly those more interested in reporting than writing—the inverted pyramid still rules. For decades, the inverted pyramid has been sacred to journalism, requiring reporters to provide the most important facts at the beginning of the story with details in decreasing importance toward the end. One of the main reasons for the popularity of this structure was to accommodate old layout techniques in which stories that were too long for the allotted space were simply cut off at the end. Although many reporters still use the inverted pyramid for their news stories, printer’s tools (and online publishing) have evolved to allow for more flexibility in page layout, and an increased interest in narratives that began with the rise of New Journalism in the 1960s gave other, more creative forms of storytelling a legitimate place in reporting.

Despite that, when Roy Peter Clark first identified a new journalism story structure in the early 1980s—the hourglass—newsrooms reeled. New structures were already old news to the feature magazines for which New Journalist Hunter S. Thompson had been writing narrative stories for more than a decade, but they were virtually unheard of in daily journalism. Clark was uniquely qualified to identify the hourglass story structure since he had been a college literature professor before making the leap to journalism (a reversal of what often happens today). Clark described the hourglass as consisting of three sections: the top, the turn, and the narrative.2 The idea was that this form allowed journalists to offer all the information they were used to including (and readers were used to seeing in the inverted pyramid structure) right up front, while allowing them to use their narrative skills to tell a more complete story at the end. Clark’s discovery, while not new, helped legitimize new ways of practicing journalism that are more relevant than ever today.

Make the details memorable

Often when a journalist has spent a great deal of time with a subject or researching a story, the sheer number of interesting facts and ideas can start to overwhelm. These facts may be complicated or layered, or require a great deal of explanation by the journalist. Providing lengthy descriptions of these observations may make what should be an engaging story dull, confusing or even unreadable. A skilled journalist will find ways of letting the story tell itself. Remember that an audience is interested in the story and its characters, but usually not the storyteller. When reporting a story, a journalist should always be on the lookout for facts, quotes, and other details that directly show the audience what no amount of descriptive language ever could. This is the fastest, most compelling way to tell a story.

Let’s say you just spent a day with a political candidate. You return home or to the office at the end of the day with a pile of notes—scraps of paper, brief audio recordings on your phone, and photos and comments you tweeted to tease the story. It’s a good idea to immediately isolate some of the more revealing things you saw or that the subject said. You can be reasonably sure that whatever stood out for you will also stand out for your audience. Considering how you might describe highlights of the story using the limited character counts of social media may help you decide which items are most revealing. Think about actions and words that need no explanation. Think cinematically.

For example, you interview an accused mobster with a terrible reputation for ordering hits on his rival gangsters. He lives with his mother, who brings both of you tea and cookies, including anisette—his favorite, according to Mom. Include that fact. The mobster has a pet rabbit that sits on his lap throughout the interview. Include that fact too.

Instead of explaining that he has discriminating tastes, simply show him (in print or on video) enjoying his “favorite” of Mom’s cookies. Instead of explaining that he loves animals, show him cuddling his pet rabbit. Also try to get him to talk about his pet. What’s its name? What’s so special about it? The mobster’s response—although it may be calculated—may surprise you. After all, what mobster looking to improve his public image wouldn’t want to shift attention to his pet rabbit? Even small details like these create a much clearer, more telling picture than any amount of description could, no matter how well written.

Less is more

Compression is discussed in detail in Chapter 4, but even when you’re producing feature or other long-form stories (this includes all story forms—not just print), keep the adage “less is more” top of mind. Just because a story can run longer doesn’t mean it can be fat or overloaded with extraneous detail. No one wants to waste time with irrelevant information. Feature writing isn’t creative writing. It still needs to get to the point.

Resist the temptation to overly quote your subjects. Limiting yourself to only the most interesting short quotes will help your subjects seem more engaging and keep the audience moving quickly through the story, eager to learn what happens next. Resist the temptation to include interesting or fun details that do nothing to advance the story or explain its characters or their actions. If you ever find yourself wondering if a paragraph, photo or video clip is needed to tell the story, take it out. Just asking this question usually means it can—and should—go. If you later realize that text, photo or video was critical to the story, you can always add it back in again. Also try to give yourself time between drafts. It can be difficult to see where a story can be edited when you’ve been staring at it for hours. Give yourself as much time as possible—ideally a day, but an hour or even twenty minutes is better than nothing—away from the story. Or, better yet, let someone else take a look at the story to suggest needed cuts you may not have been able to identify yourself.

Don’t Forget your Role

Despite the preceding discussion of objectivity, neutrality, and approaches to interviewing reluctant subjects, keep in mind that you, like your subjects, readers, viewers or listeners, are human. While it can be difficult to remember that when you’re hard at work tracking down unwilling sources or desperately digging for answers, an obsession with uncovering facts and exposing wrongs is never an excuse to act unethically.

Always be honest about your angle or general intentions before an interview. Don’t misrepresent yourself or take advantage of those (including children) who are not media savvy to get access to a key figure in your story, and never lose track of the reason why you are doing something. That should inform your decision-making about how best to proceed with a story. Reporters often possess a tremendous amount of power relative to their subjects, so they must be mindful of their capability to influence the lives of others in both positive and negative ways. Remember, even bad guys have rights. And don’t forget that it’s not up to you, the journalist, to decide who’s a bad guy. Everyone deserves their day in court.

If you ever find yourself deep into the reporting of a story and wondering how far you should go, it’s a good idea to step back and consider the goals of your reporting. Is your goal to show your audience that Mayor Jones is corrupt, or is your goal to ruin Mayor Jones’ reputation? If your goal is the latter, it may be time to revisit your reasons for entering journalism. Despite the increase in opinionated journalism that has coincided with the rise of blogs and online reporting, the journalist is not judge, jury, and executioner. Rather, journalism is about informing audiences, then letting those audiences draw their own conclusions. The more closely journalists honor that fact, the better journalism’s reputation will be going forward.

Summary

Journalists have long used narrative tools and techniques to tell news stories in compelling ways. They should be familiar with narrative storytelling techniques so they can apply them when appropriate.

Stories are more than just collections of facts. They put ideas in context and help people make sense of the world. Journalists can use storytelling tools to make their reports both interesting and relevant to their audiences. One of the most important ways of doing this is to put a human face on an issue.

Key to good stories are good questions and answers. Journalists with strong interviewing skills get the best quotes, and great quotes make for compelling narratives. To get the best from interviews, a reporter must be flexible and prepared to shift gears if necessary. She needs to have a list of essential questions, then be prepared to depart from the list when necessary.

Stories should start strong, with drama or universal questions and themes. Storytellers think cinematically. Whenever possible, they let stories tell themselves by showing revealing actions or including pithy quotes instead of editorializing or engaging in lengthy descriptions.

Journalists will be well served by starting the reporting process with guiding questions or a working thesis. While they won’t have a precise thesis until they finish reporting, having a sense of where they expect to end up will make it easier to focus the story as they go. Interview subjects will also be more willing to talk if they have some idea about the story’s focus.

A story’s content should determine its structure. Traditionally, news stories have followed the inverted pyramid form in which the most important information appears at the beginning, followed by all other information in decreasing order of importance.

Finally, the most successful storytellers never forget that they, like their subjects, are human. This helps guide their decision-making as they report. While the reporter should never be a focus of the story, she must also remember her reporting goals and not let personal agendas interfere with journalistic objectivity. The more honest and straightforward a journalist is about her reporting, the easier time future journalists will have gaining access to the information and sources they need to tell compelling stories.

Journalist’s Toolkit

Storytelling doesn’t require any special tools beyond what journalists now use to report all their stories. Applying narrative tools and techniques to journalism mostly just requires journalists to think differently about the work they do and the goals of their reporting.

Skills

Listening

Interviewing

Writing

Editing for meaning and compression

Basic photography and photo editing

Basic video shooting and editing.

Tools

Digital audio recorder

Smartphone or tablet computer or a digital video or still camera

Laptop computer

Basic photo, video, and audio editing software.

Application

- Read a news feature in a magazine or online. Identify the author’s narrative techniques. Analyze the lead, the structure, the characters, and the presentation of facts and quotes. Explain how these narrative techniques affected the story’s readability and how the story would differ without them.

- Write or rewrite a news story you reported using narrative techniques. Optional: Submit the story to a community or student publication.

- Conduct an interview for a story you are reporting in a subject’s home or office. Use a digital voice recorder, smartphone or video camera to record the interview. During the interview, take notes on revealing details that could help “show” the subject’s personality without your having to describe it. Pay attention to less obvious details such as the way the subject treats an assistant or the way he handles an unexpected phone call. Also look around for evidence of the subject’s true self. Write a character study of the subject based on your objective findings during the interview.

Review Questions

- What is narrative and how does it relate to journalism?

- Why would a journalist want to apply narrative techniques to her work?

- What does it mean to think cinematically when you write?

- What does it mean to put a human face on a subject, and why would a journalist want to do that?

- Why is listening important to journalism? What about observation?

- Are there any circumstances in which narrative techniques would be inappropriate for a journalist?

References

1. Tompkins, Al. Aim for the Heart: Write, Shoot, Report and Produce for TV and Multimedia (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2012).

2. Scanlan, Chip. “The Hourglass: Serving the News, Serving the Reader,” June 18, 2003, Poynter.org, http://www.poynter.org/how-tos/newsgathering-storytelling/chip-on-your-shoulder/12624/the-hourglass-serving-the-news-serving-the-reader/.