Preparing Common Business Documents Used in Finance

In Chapter 4, we provided you with a disciplined approach to the writing process. That process can be applied to a broad range of documents. In this chapter, we offer guidance for writing common documents in the finance field. Using redacted documents from real-world communications, we provide you with tips for writing routine, positive, negative message, and persuasive messages.

Writing Routine and Positive Messages

Routine messages include those messages you will write that elicit a neutral response from your audience. In many ways, these messages are easy to construct because you won’t have the added work of overcoming audience objections to your message. Routine messages usually do one of two things: (a) Convey information to your audience or (b) seek clarification from your audience. Typical routine messages include announcements about new or modified policies, information about upcoming meetings, routine reports (e.g., travel reports and sales reports), and denials of minor requests.

When writing routine messages, you should usually use the direct approach. In the opening of the message, identify the main idea of the message. Then, you provide a brief overview of the message’s major points. For longer messages, you may want to set off each of the major points by using a bulleted list. In the body, provide all of the details needed by your audience. Finally, provide a brief, cordial closing. If the reader needs to take action, then make sure that you call the reader to action.

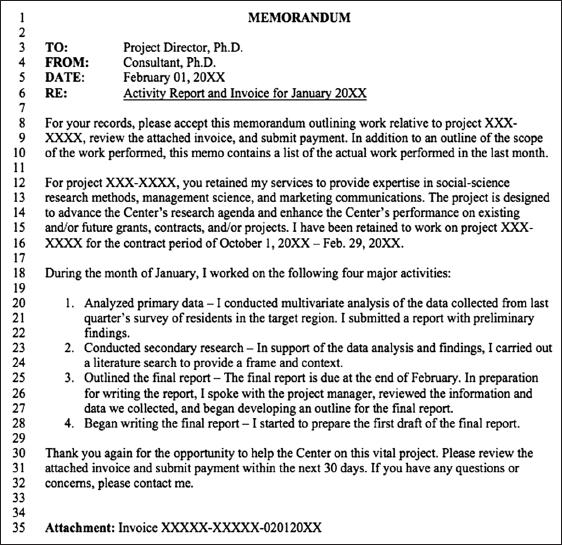

Consider the sample routine message in Box 5.1. The memo is an actual activity report submitted to a client by a consultant. Clients often request activity reports from their consultants each time the consultant submits an invoice for payment. As you can see, the memo follows our advice for writing routine messages. In particular, look at the following portions of the memo:

Box 5.1 Typical routine message

Lines 8–9: The writer makes clear the memo’s main idea.

Lines 9–10: The writer provides an overview of the message’s major points.

Lines 12–28: The writer expands on the overview provided in the introduction.

Lines 30–32: The writer closes cordially and calls the reader to action.

Positive messages are a pleasure to draft because you have the advantage of knowing your audience will be happy. Positive messages include announcing positive earnings and sales data, announcing employee promotions, saying yes to requests, and loan quotes. Similar to routine messages, you want to identify the main idea right away in the opening. Then, provide the reader with an overview of the major points that will be included in the message’s body. In the body, provide the reader with all necessary information, including information about action the reader needs to take, if any. Write a cordial closing, referring back to the positive news, if that is appropriate.

In Box 5.2, you can see how our approach is put to use. The message is an actual e-mail message from a nonprofit organization to a student in Jason’s class who participated in a letter-writing contest to help the non-profit raise money. On Lines 3–4, the writer gets right to the point. On Lines 4–5, the writer provides an overview of the body. Lines 7–11 give the reader the information that needs to be submitted in order to cash in on the reward. The writer closes cordially and refers back to the positive news.

The letter in Box 5.3 is a positive news message. It is an actual loan quote letter that we’ve redacted in order to use in this book. As you can see, this letter follows our advice on delivering good news:

Lines 13–14: The writer delivers the main idea.

Lines 14–16: The writer provides an overview of the message’s body.

Box 5.2 E-mail conveying positive news

Box 5.3 Loan quote

Lines 18–20 and the table: The writer provides the loan quote needed for the reader to make a decision about acceptance of the terms.

Lines 23–27: The writer calls the reader to action and describes what to expect in the future.

Line 29: The writer closes cordially.

Writing Negative Messages

In the finance profession, you will undoubtedly have to write negative messages. You may have to deny credit to a client, report on losses, or tell job candidates that they did not get the job, among other things. Regardless of the purpose for delivering negative messages, you will want to keep the following goals in mind:

Deliver the negative messages

Make sure that your reader accepts the conclusion

Demonstrate that you are fair

Limit your liability

Avoid inviting a back-and-forth about the news

Minimize the damage to your reader

It is important in delivering the negative messages that you avoid being bad. Your reader’s feelings matter. You need to tell the truth and deliver the negative messages, but it is critical that you do your best to minimize the negative impact of the message. You may be saying no to your reader today, but who knows what the future may hold for your relationship. The approach you take in constructing your message will help you achieve your goals when delivering negative messages.

When writing negative messages, you should usually use an indirect approach, for all of the reasons we discussed in Chapter 4. Consider opening your message with a buffer. A buffer is a neutral statement that gently prepares the reader for the negative messages to come. Readers expect to see words such as “congratulations” when the news is good. So, a gentle neutral statement often tells readers that the news is going to be bad before they actually see the news. You also want to keep the focus of attention off your reader. You can accomplish this by explaining the decision-making process that led to your conclusion. When you close, try to make what Jason calls “a future-looking statement.” In other words, try to say something positive about the future. You may be saying no today, but the reader has a positive future to look forward to.

You have already read the positive message that one of Jason’s students received from a nonprofit organization for winning a letter-writing contest. The other finalists received a negative message informing them that they did not win the contest. The negative message is in Box 5.4. As we highlight how this message follows our advice, you should also consider the differences between this message and the positive message that was sent to the winner.

As you can see in Lines 3–4, the letter opens with a neutral buffer before delivering the negative messages in Lines 4–5. The writer demonstrates fairness in the body of the message by describing the decision-making process in Lines 7–12. Finally, the writer closes by thanking the reader and making a future-looking statement.

You can also see how our advocated approach to negative messages can be applied to common finance documents. Consider the budget memo in Box 5.5 to residents of a housing complex from their board of directors. Line 8 opens with a positive buffer. The negative messages is delivered on Lines 9–10. You can see on Lines 11–15 how the Board describes the process they went through over the year to keep fees low. In the last two lines, the Board talks about the future and says that the fee increase is “a practice that will enhance the value of your unit.”

Box 5.4 Sample negative message

Box 5.5 Negative messages budget memo

Writing Persuasive Messages

In writing persuasive messages, your decision to use a direct or indirect approach will ultimately depend on your reader’s reaction to your request. The more inclined your reader is to say no, the more likely you are to move away from a direct approach toward an indirect approach. In being persuasive, you need to consider a few things.

First, always answer the What’s In It For Me? (WIIFM) question. If you want your readers to say yes to a request or carry out a certain action, they have to know what’s in it for them. Tell them what’s to gain or lose. Second, discuss the benefits of your ideas, not the features. Jason tells his students that one of the best ways to learn about persuasive communication is to watch QVC television. In particular, watch Mr. David Venable, host of In the Kitchen with David. When he sells food products or kitchen accessories, he doesn’t focus on what the accessories are made from or what the cooking process is like. He tastes the food or uses the accessory. If the experience is particularly delightful, Mr. Venable does the happy dance. It may sound silly, but he is selling the benefit of the products, and he sells millions of units. Third, consider the factors driving your reader toward saying yes and those factors restraining your reader from saying yes.

Enhance Your Credibility and Likeability

Volumes of research exist on how we can make our messages more persuasive, and one could probably organize a small army with the gurus who offer advice in this area. We will add our names to that list by sharing some simple things to keep in mind when crafting persuasive messages.

Earlier in this book, we discussed that credibility fuels your communication. Nowhere is that more true than in crafting persuasive messages. One of the things we have learned from research is that people commit what is called the genetic fallacy. In other words, people have trouble separating the message from the sender. They are more likely to accept a bad idea from a genius than they are a brilliant idea from a ne’er-do-well. The two characteristics that seem to matter most when these people assess senders of persuasive appeals are credibility and likeability.1

Credibility comprises your trustworthiness and competence. So, the recipients of your persuasive messages will ask themselves, “Can I trust this person, and can I think this person knows what he or she is talking about?” Look at your professional network. Do you surround yourself with people who can’t be trusted and don’t know what they’re talking about? We certainly hope not. And this is important because we all tend to naturally like people to whom we ascribe greater credibility. In many cases, you will find that if you are perceived as credible and likeable, a good bit of your persuasive work has already been done.

But what if your reader doesn’t know who you are? Are there things you can do in your written messages that will enhance your credibility and likeability? Yes, you can enhance your credibility and likeability in the following ways:

If you have expertise, share it. Don’t assume people know your background.

Show your reader that you’ve done your research.

Describe how you have delivered on your promises in the past.

Demonstrate that you understand your reader’s perspective.

Demonstrate a genuine concern for your reader’s well-being.

Share personal stories—when they are appropriate—to show your audience you trust them enough to share their confidence.

Establish common ground with your readers. Highlight shared goals.

As you write those persuasive appeals, remember that your message needs to speak about both your ideas and you. Your audience is assessing both.

Consider the e-mail, which is a real-world persuasive message, Box 5.6. In the e-mail, the writer is trying to sell a product to improve lease administration productivity within the reader’s corporate real estate firm. The writer does a number of things well. First, the message attempts to answer the WIIFM question. In fact, on Lines 12–19, the message suggests that the new product will help the reader find answers to many important questions. The writer also establishes credibility by making a reference to the company’s areas of expertise and its track record of success (Lines 21–28). The e-mail closes with a clear call to action.

Box 5.6 Sample persuasive message

Understand the Six Principles of Influence

In addition to understanding how your audience responds to you, you should also understand how they respond to important social cues. To help you better understand these cues, we encourage you to read the work of Dr. Robert Cialdini on the six principles of influence (see Box 5.7).2 We share the six principles here with ideas for how you can apply them to your persuasive messages, but to master the principles, you should read his books.

We have already discussed the liking principle. When people like you, they are more likely to say yes to a request you make of them. For example, LuLaRoe parties are becoming increasingly common (think Tupperware or Pampered Chef parties, but with dresses). Your friend hosts a LuLaRoe party and invites you over to try on some dresses. When she asks you to buy a dress, you are more likely to say yes simply because you like your friend. We often choose friends who are similar to us. Therefore, one of the best ways to make yourself more likeable is to demonstrate how you are similar to your audience.

The principle of authority teaches us that people are more likely to comply with requests when they come from perceived authority figures. The term “authority” sounds a little heavy-handed, so you can think of it as credibility. As we suggested previously, you have a number of tactics at your disposal to enhance your credibility in your written messages. Employ those tactics.

Box 5.7 Robert Cialdini’s six principles of persuasion

Liking

Authority

Consistency and commitment

Reciprocity

Scarcity

Social proof

The principle of reciprocity teaches us that people are more likely to comply with your requests when they owe you a favor. One of the best ways to make yourself more persuasive is to make yourself helpful. Get into the habit of doing good for others. Your favors are not only a great way to build relationships, but they are also a great way to getting to yes before you even make a request.

The principle of commitment and consistency teaches us that when people commit to goals, they are more likely to work toward those goals. People also want to be seen as acting consistently with their expressed values and ideas. We both love doing CrossFit, and at both of our boxes (i.e., gyms), members are encouraged to write their fitness goals on a whiteboard for everyone to see. It’s a great motivational tool because it holds the members publicly accountable for their own goals. One way you can use this principle in your writing is to remind your readers about their goals and values. Then, you can demonstrate how your request is in line with those goals and values.

The scarcity principle teaches us that people want more those things they can’t have. Diamonds are expensive because their flow to the marketplace is tightly restricted. We see the scarcity principle in action when products are in short supply, when offers are for a limited time, and when few seats are available. Scarcity creates a sense of urgency for your reader. Put timelines on your proposals, demonstrate how rare an opportunity you are presenting, encourage your readers to act, and remind them of what they stand to lose if they don’t comply with your requests.

The social proof principle teaches us that when people are unsure of what they should do, they look to see what others are doing. When making persuasive appeals, you can demonstrate for your readers that other people who are just like your readers are complying with your request. Social proof is a powerful tool of influence.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we offered guidance for writing common documents in the finance field. Using real-world documents, we provided you with tips for how to write routine, positive, negative, and persuasive messages (see Table 5.1 for key takeaways). We also highlighted Robert Cialdini’s six principles of influence to help you understand simple ways to gain compliance for your requests. In the next chapter, we turn our focus away from writing business messages to preparing and delivering effective business presentations.

Table 5.1 Chapter 5 takeaways

Message type |

Common examples |

Tips |

Positive |

Positive earnings Positive sales data Employee promotions Approving requests Loan quotes |

|

Bad news |

Denial of financing Loan rejection Poor investment Performance Dividend reduction Increase in costs or fees |

|

Persuasive |

Sales proposal Project proposal Financing requests Appeals Loan application Product marketing |

|