Preparing and Delivering Finance Presentations with Maximum Impact

Presentations are a reality for finance professionals. No product or service offered by your company hit the marketplace until a series of presentations were delivered. Whether you enjoy delivering presentations or hide behind your computer screen in hopes that nobody will EVER ask you to deliver a presentation, you might as well face the fact that you will have to deliver presentations throughout your career.

Now that you’ve given that fact a minute to settle in, let’s get to work enhancing your presentation skills. In this chapter, we help you make appropriate choices at each stage of the presentation design and delivery processes. You will learn how to:

Craft a powerful introduction, body, and conclusion

Organize content for best results

Develop an effective call to action

Deliver with confidence

Build multimedia slides that won’t bore your audience members and insult their intelligence

By following our advice, you will transform into a virtuous presenter. So, let’s begin the journey by exploring the four virtues of business presentations.

Becoming a Virtuous Presenter

You may read the phrase “virtuous presenter” and wonder if maybe we’re setting unreasonably high expectations. We have a friend who works in consulting who likes to use the phrase “aim for perfection to achieve excellence.” We agree. Given the significance of business presentations, modern professionals should not aim to be good presenters; they should try to be the best. They should try to be virtuous.

Box 6.1 The four virtues of the virtuous presenter

Fortitude—having the courage necessary to get in front of an audience and be the presentation

Prudence—demonstrating the wisdom to make the right choices and put in the hard work necessary to design and deliver a powerful presentation

Justice—treating your audience fairly by not putting them through a boring presentation with all the problems that you don’t like to experience when you’re an audience member

Temperance—exercising control over your use of multimedia software and showing restraint over your tendency to rely on defaults you’ve probably heard that when asked about their greatest fears, people often rank fear of public speaking higher than death. Comedian Jerry Seinfeld used to quip that people at a funeral would rather be in the casket than delivering the eulogy.

A virtue is nothing more than a quality that is good, useful, or desirable. People can be virtuous in a number of ways. We focus our discussion on four virtues that some of you may have heard before (see Box 6.1):

Fortitude

Prudence

Justice

Temperance

These are the four cardinal virtues in the Catholic faith. Although we don’t digress into a discussion on religion, we do argue that virtuous presenters exhibit these four virtues. As you will see, the four virtues are not mutually exclusive. For now, let’s examine them one at a time.

Fortitude

The first virtue of the virtuous presenter is fortitude. We define presentation fortitude as having the courage necessary to get in front of an audience and be the presentation. People fear delivering presentations. In fact,

Why are people so afraid of public speaking? Some social psychologists argue that the answer lies in human evolution. Humans are social beings, in part, because we once lived in a world where we were not at the apex of the food pyramid. On a bad day, our ancestors could easily find themselves on the dinner menu of larger predators. Being social provided humans with the ability to alert one another about danger and to work together to defend against attack. Finding oneself ostracized from the group could spell doom. In a recent Psychology Today article, Dr. Glenn Croston related these primitive fears to our modern fear of public speaking:1

When faced with standing up in front of a group, we break into a sweat because we are afraid of rejection. And at a primal level, the fear is so great because we are not merely afraid of being embarrassed, or judged. We are afraid of being rejected from the social group, ostracized and left to defend ourselves all on our own. We fear ostracism still so much today it seems, fearing it more than death, because not so long ago getting kicked out of the group probably really was a death sentence.

Our fears of delivering presentations can often lead to poor practices. Fear can cause us to avoid situations where we may be called upon to speak. But avoiding those situations in business can have deleterious effects on your career trajectory. Those with fortitude seize those opportunities. Jennifer Savini, a senior internal auditor and senior financial analyst for a major provider of health insurance, told us about the role of communication and presentation skills in her career.

Good communication skills are needed in order to meet expectations in regards to my job requirements; however, excellent communications skills are required in order to exceed expectations for my role. ... I had the opportunity to prepare and execute a pre-sentation for executive level presidents in my firm. ... There were other members of my team that possessed greater knowledge but lacked the communication skills necessary to present. This allowed me to gain valuable exposure to important decision makers.2

Jennifer Savini

Sr. Internal Auditor/ Sr. Financial Analys Health Insurance Provider

Our fears may lead us to do what we perceive as safe. In other words, we look at what other presenters do and mimic their presentation behaviors. That works well if you’re observing people who are excellent presenters. If not, then you’re just copying their mistakes. And that is too frequently the case. For example, you should NEVER begin your speech with “Hello, my name is ....” In most business presentation situations, the audience already knows your name. And if they don’t know it, will it hurt them to wait 20 seconds to hear it? Audiences MUST be engaged in the first few seconds of a presentation. Simply telling them your name will not engage them. We see other people start presentations that way all the time, so we copy that “safe” behavior.

Fear also causes us to do things like read from prepared statements or from our multimedia slides. That is insulting to our audience members. But the alternative is to actually be the presentation—to be the center of attention. That is scary!

Virtuous presenters have some fear, but they have even more fortitude. They think about what they’re afraid will go wrong during a presentation, and they take the steps to prepare for those possible scenarios. They seize the opportunities presented to them. They practice until they know their material. They practice the right way. They don’t hide from their audience. They engage their audience. They become the presentation by preparing effective slides and using best practices instead of doing what they think is safe. If you think you’re up for the challenge, we give you tips to put your fortitude to work for you! Besides, we can almost guarantee that a predator won’t eat you during a presentation.

Prudence

Presenters who demonstrate prudence exercise the wisdom to make the right choices and put in the hard work necessary to design and deliver a powerful presentation. Too many people deliver lackluster presentations simply because they did not make the right choices about their time management and failed to prepare themselves adequately.

Virtuous presenters conduct their audience and situation analysis. They understand their audience before delivering their presentations. They think in advance about the major points they will make and the data they will need to make those points. They consider how to organize those points. They think about the type of persuasive appeal they will make. They design slides that complement their presentation and avoid common errors like creating slides with too much text. They consider whether they need handouts. They put in the time to practice.

Justice

Justice is like the golden rule of presentations. You demonstrate justice when you treat your audience fairly by not putting them through a boring presentation with all the problems that you don’t like to experience when you’re an audience member. We have had the displeasure of sitting through hundreds, maybe thousands, of boring presentations. And we’re sure you have seen some presentations that made you roll your eyes and wish you were anywhere else in the world.

These boring presentations share some key characteristics, all of which are under the speakers’ control. In these presentations, the speaker:

Does not know the material

Did not know the audience

Did not practice

Read from prepared notes or off the multimedia slides

Prepared slides filled with words

Failed to engage the audience through eye contact, vocal dynamics, or body language

Went over the allotted time

We’re sure that you agree that these presentations are atrocious. You can identify the characteristics that make a presentation boring. In fact, most people know a bad presentation when they see one. You don’t need to be a trained expert. And yet, people continue to make the same mistakes. That’s not fair! Presenters who deliver presentations with these characteristics have no sense of justice. They are torturing their audiences. Let’s resolve to do better. Let’s be virtuous. Let’s take the steps necessary to demonstrate that we have a sense of justice and we respect our audiences.

Temperance

You can demonstrate temperance by exercising control over your use of multimedia software and showing restraint over your tendency to rely on defaults. We once heard a comedian say that the reason why bullet points are called bullet points is because of the bullets that audience members want to put in presenters who overuse bullet points (see Figure 6.1).

Perhaps you’ve heard of “death by PowerPoint.” This is the idea that business audiences have seen too many PowerPoint slides.

So let’s do away with PowerPoint and related multimedia slide software! Not so fast. The software is not the problem. The problem is our use of the software. We tell our students that engineers and IT people created PowerPoint. They are not presentation experts. So why take slide design suggestions from them? Exercise your own discretion and your own imagination in constructing slides. Why use default slide layouts, default fonts, or default anything? When we rely on defaults, we bore our audiences to “death.” And we certainly don’t create anything that’s memorable. Later in this chapter, we give you detailed advice for slide design. For now, consider the following guidelines when thinking about your use of multimedia slide software.

Figure 6.1 Audience member experiencing death by PowerPoint

Use multimedia slide software only when necessary.

Use your imagination. Do not rely on defaults.

Use visuals that evoke an emotional response. Do not simply fill the slides with words and bullet points.

Display only that information or data that is necessary to make your point.

Avoid reading from your slides.

If you allow these simple guidelines to direct your use of multimedia slide software, you will decrease the likelihood of putting your audience through “death by PowerPoint.” And you’ll be one step closer to being a virtuous presenter.

Now that you have a better understanding of what it takes to be a virtuous presenter, let’s take a look at the major elements of a business presentation. In the following sections, we take you through the process of preparing a business presentation. First, we ask you to answer the following question about your presentations: What’s the big idea?

Developing the “Big Idea”

Presentation professional Nancy Duarte writes about developing a presentation’s big idea in at least two of her recent books.3 She argues that you should see your presentation as world changing. If most of your business presentations are persuasive in nature, then aren’t you in fact changing the world in some way? If you spend some time thinking about that idea, you will discover it’s quite powerful. Putting yourself into the frame of mind created by the thought that you’re changing the world will have a number of meaningful outcomes for your presentation preparation and delivery. And one of the first places where we see the impact of the “world-changing” attitude is in how you frame your presentation.

Most presenters, when asked about their presentation, will share with you their topic. For example, a speaker may tell you that he or she is preparing a “Summary of Company X’s financial ratios,” or building a presentation about “an investment opportunity.” Those are topics and they sound emotionally detached and not terribly compelling. In fact, those topics wouldn’t require a presentation. The speaker could instead write up a review and e-mail it to the decision makers.

Think about why one might conduct a summary of financial ratios. One reason for doing so is to make recommendations about buying, selling, or staying away from an investment in a company’s common stock. So what’s the big idea?

According to Nancy Duarte, a big idea requires two elements to be impactful. First, the big idea needs to share your perspective and tell the audience what they should do. If you are making a persuasive appeal, it’s important to be very clear from the beginning what you need from your audience. Second, the big idea should tell the audience what is at stake. What will happen if the audience takes your advice or fails to take your advice? State your big idea as a complete sentence and let it guide you through all the decisions you will make when preparing the presentation. Instead of saying your presentation is “a summary of Company X’s financial ratios,” you could say something like “You should not purchase common stock in Company X because its financial ratios indicate it will likely be bankrupt within the next six months, and you will lose your investment.”

Not only is the big idea as expressed previously more powerful, but it will also affect the way you present the information. Instead of thinking about simply presenting data on things like an Altman’s Z-score, the big idea will make you think about how you can best make your case. What information is required to be more persuasive? How should the information be organized to have a maximum impact? What types of persuasive appeals should you make? Should you develop handouts or multimedia slides? How much involvement do you want from your audience?

These decisions are all influenced by how you think about what your presentation is about and what you know about your audience and situation. Now that you have a sense for writing a big idea, let’s take a look at the basic parts of a presentation, beginning with the beginning.

Starting with a Bang

If you recall from the beginning of this chapter, we suggested that one should never start a presentation with “Hello, my name is ....” It isn’t virtuous. Many presenters begin their presentation that way because it is safe and provides a soft opening to the presentation’s content. In most business presentation situations, the audience will know who you are because they work with you, you’ve been introduced, or your name is on a handout or on the multimedia slide at which they’re looking. Even if your audience doesn’t know your name, does it really matter if they have to wait an extra moment or two to hear it?

The introduction is your opportunity to hook your audience, to direct their attention to your big idea. Introductions are brief, relative to the body of the presentation, but they are important and have a lot to do. In your introductions, you will need to:

Capture the audience’s attention

Explain your big idea

Identify yourself (if you haven’t been introduced)

Establish your credibility

Provide a road map for the presentation

At the beginning of any presentation, the first thing you need to do is capture the audience’s attention. Even at meetings where your presentation is the main purpose of the meeting, your audience members will all be thinking of different things when you begin. You need to get them all on the same page and give them a compelling reason to listen to the presentation. We do describe some ways that you can hook your audience, but keep in mind what the hook will do. The hook puts the audience in a particular frame of mind. It sets the mood. What frame of mind or emotion do you want to evoke during the presentation? The hook creates a theme for the presentation. You should refer to the hook throughout the presentation. The repetition can make your big idea and supporting points easier to remember. Let’s take a look at tactics you can use to capture your audience’s attention (see Box 6.2).

Box 6.2 Tactics for capturing audience attention

Share a compelling or novel statistic

Tell an emotional story

Describe a serious problem

Answer the WIIFM question

Ask a rhetorical question

Use humor

Show a captivating video

Share a compelling or novel statistic. Note that we didn’t simply say share a statistic. The statistic has to be something that startles your audience and makes them think. That means the statistic has to be truly compelling for your audience.

Tell an emotional story. People enjoy stories and they are an excellent means for humanizing your topic. Provide your audience with a story that exemplifies the stakes related to your big idea. In some cases, you can even provide your audience with a realistic hypothetical example. You can use stories to create a cliffhanger for your audience. Cliffhangers make it easier to refer back to the introduction and people will pay attention because they want to know how stories end. Stories should involve conflict that gets resolved. Ideally, you can empower your audience through your presentation to resolve the conflict.

Describe a serious problem. If you are attempting to make a persuasive appeal, you can always paint a picture of the world as it exists today versus the world as it could be if the audience follows your advice. Contrast is a great way to help audience members think about your big idea.

Answer the What’s In It For Me? (WIIFM) question. One of the easiest ways to get the audience to focus on your topic is to tell them upfront what is in it for them.

Ask a rhetorical question. These questions are designed to get audience members thinking. For instance, if you believe that buying a company’s common stock will lead to huge losses for your audience, you could begin the presentation by saying, “If our company loses $10 million because of a poor investment choice, how many people would lose their jobs in order for us to make up for that loss?”

Use humor. As long as the situation is appropriate, you can tell a joke. The joke should be tasteful and never made at the audience’s expense.

Show a captivating video. Be sure the video is relevant and brief. Remember that you are the presentation and you won’t want a video to do the talking for you. If you use a video, try to test out the equipment in advance, if possible.

Be creative with your attention-grabbing hook. You can use some of these tactics in combination. All of these tactics take more time than merely introducing yourself, but they all provide a much higher return on your investment of time and energy.

After you captured the audience’s attention, share with them your big idea. You’ll share with them a bold position along with a picture of what’s at stake. The audience will then need a reason to trust you. So, you’ll need to follow up the big idea with statements that establish your credibility. Here is where you’ll need to show your audience that you have direct experience with the matter at hand or have done extensive homework. Tell your audience what makes you a person whose big idea should be considered seriously.

Finally, you should provide your audience with a road map. What are the three to five points that you will discuss in the body of the presentation that will offer support for your big idea? You may have many points that support the big idea, but your audience will be able to remember only so many of them. So make strategic decisions about which points are most important and limit the presentation body to those three to five points.

To help you make that decision, ask yourself, “What are the three to five things my audience must remember in order for this presentation to be successful?” You will want to repeat these points at least three times throughout the presentation; once in the introduction, once in the body, and once in the conclusion (see Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2 Repetition of supporting points in presentations

The presentation itself is like a repeating cycle, where repetition reinforces the points you want the audience to remember. Here’s an expression we share with our students and clients: “Tell them what you’re going to say. Say it. Then, tell them what you just said.”

Keeping Your Audience Engaged Through the Body

As we’ve just discussed, the body of your presentation will include three to five supporting points. In thinking about those points, you will want to sequence them for maximum impact. As a general rule, we tell people to put the most important point either first or last, because the audience will be more likely to remember them. Another way to organize your points for maximum impact is to create contrast, such as us versus them, best versus worst case scenario, the past (or present) versus the future, what can go wrong versus what can go right, and risk versus conservatism.

The supporting points will need to be buffered by sufficient evidence that you gathered while researching the topic. However, the body of the presentation is not simply the provision of supporting points and accompanying evidence. You still have to work hard to keep your audience engaged and awake. You have a number of options for doing so, including:

Balancing emotion and logic

Using effective imagery

Using your delivery style

As we discussed in Chapter 2, it’s important to consider the role of emotion in business communication. Business presentations should include logical arguments—features of products, primary and secondary evidence, and case studies. However, logical arguments are not always going to provoke the emotions required to be persuasive. So, balance product features with product benefits, primary and secondary evidence with suspenseful stories, and case studies with answers to the WIIFM question.

You can also use imagery to paint a more colorful picture of your data. The tools of imagery we can use include analogies, metaphors, similes, personal anecdotes or statistics, and best or worst case scenarios. If we take a presentation in which the speaker is trying to convince managers to rein in spending, the speaker may use the following devices to enhance imagery:

Analogy—Solving our company’s spending problems will require an intervention similar to helping a drug addict overcome an addiction. Our managers need tough love.

Metaphor—Our company’s spending problems are like a noose around the neck.

Simile—Our manager’s spending problem is creating a bubble in our budget that threatens to burst.

Personal anecdote—My parents taught me to spend no more money than I actually have. Unfortunately, our managers did not have my parents raising them.

Best or worst case scenario—If we can’t put limits on our managers’ spending, we will have to shut down facilities and lay off employees.

In addition to imagery, you can use your presentation delivery to keep audience members engaged. For now, we share some tips from the Presentation Zen Garr Reynolds. To keep your audience engaged, you should be engaged. Why should the audience care, if they don’t believe you care? If your delivery style is too formal and devoid of emotion, then your audience will not feel emotionally engaged.

Remember that emotions are contagious; smiling and displaying natural, authentic emotions will help your audience’s response to the presentation. You can stimulate your audience’s curiosity by asking questions like “What do you think happens next?” and expressing your own curiosity by saying things like “How incredible!”4 We return to delivery style in greater detail later in the chapter. For now, suffice it to say that you should move, make eye contact, modify your speaking voice to create emphasis, and speak loudly and clearly.

Closing Powerfully

A few years ago, Jason attended a national union event. At one of the presentations, the speaker made a powerful argument against the reduction of state economic support for higher education. The speaker was smart, witty, and well reasoned. He made clear points supported by data and personal anecdotes. It was an ideal presentation and quite moving. The speaker wanted the audience members to contact their state legislators to speak out against budget cuts for higher education. Jason never called his legislator. Why not?

Jason didn’t call his legislator for the same reason that we are willing to bet most of the people in that room didn’t make the call. The presentation’s close was not well thought out. After spending the presentation about the negative consequences of budget cuts and the need for intervention, he merely said, “Thank you. Are there any questions?” The speaker must have invested considerable resources in putting that presentation together and it all fell apart at the end because he did not carefully consider the close. So now that we have an idea what an ineffective close looks like, let’s consider what needs to go into a close and avoid wasting our efforts with a poor close. A conclusion needs to do the following things:

Signal the impending close.

Reiterate your big idea and supporting points.

Make a specific call to action.

Close memorably.

First, it must provide a signal to the audience that the presentation is about to end. Although it’s a simple tactic, many speakers say, “Let me close by saying....” That little expression provides a signal to the audience that the presentation is coming to an end. Audience members tend to perk up when they believe the presentation is about to close, because it means they can leave and that they also have an obligation to acknowledge the conclusion (usually through applause). Abrupt closes, such as the one made by the union presenter did not take advantage of the opportunity to recapture the attention of any audience members who may have been daydreaming.

Once you signal the close of your presentation, you should reiterate your big idea and the supporting points. If they missed any of the points during the body of the presentation, the close presents one more opportunity to make the point. If they were paying attention, the repetition will help them retain the information.

After you’ve reminded your audience of the big idea and supporting points, challenge the audience with a specific call to action. Have you ever heard the expression If you don’t ask, you don’t get? It is equally true in presentations as it is in everyday life. This is your chance to tell the audience what you want them to do. You need to make it easy for your audience to comply. Empower your audience! The more barriers your audience members must overcome, the less likely they are to comply with your call to action. Empower your audience members to take the first steps to fulfilling your request as soon as possible. Convince your audience that if they take the appropriate actions, they will solve major problems, resolve conflict, overcome negative forces acting against them, make the future better than the present, or save the world!

In the case of our union presenter, he made no effort to overcome barriers. The presentation was delivered in Chicago to members from across the country. The speaker did not specifically ask the audience members to call their legislators. Even if he had made a call to action, what barriers were his audience members facing? They may not have known who their legislators were or how to find them. Even if they knew their legislators, they probably didn’t know how to contact them. Once they contacted their legislators, what should they say?

Jason didn’t make that phone call. He attended the conference for several more days before returning to Connecticut. In that time, other priorities crept into his life. He couldn’t remember the details of the presentation. He didn’t know what he was supposed to say. Faced with other demands for his time, he simply didn’t do it. And we’re willing to bet that the vast majority of people in that room also didn’t call their legislators. Consider how differently that could have worked out had the presenter considered more carefully the close of his presentation.

Following your call to action, have a strong closing line. Avoid simply saying, “Thank you.” It’s safe and easy. We don’t like safe and easy. The closing line should remind your audience about the introduction. If you told a cliffhanger in the introduction, then the close is your chance to finish the story. If your story involved conflict, then the close is where you resolve that conflict. If the presentation created contrast by discussing the past versus the future, here is your chance to paint a complete, beautiful picture of the future that lies ahead in contrast to the past that you painted in your introduction.

Delivering Like a Professional

Preparing an effective presentation and delivering an effective presentation are two distinctly different things. Some people are naturally gifted speakers. They are able to speak calmly and with confidence regardless of the situation. That said, presentation delivery skills are just that, skills that can be improved through practice. So, regardless of your comfort level, your skills can improve. Here are our best tips for delivering like a professional (see Box 6.3).

Be Authentic. Be Vulnerable

Have you ever started preparing yourself for a presentation with the hope that the presentation would be perfect? Delivering the perfect presentation is a noble goal. It’s also the source of tremendous mental distress. Too many times we have seen perfectly good presenters fall apart because of the stress that the drive for perfection caused them.

Box 6.3 Tips for delivering like a professional

Be authentic. Be vulnerable.

Have a conversation. Be extemporaneous.

Speak loudly, clearly, and with conviction.

Move.

Dress appropriately.

Practice the right way.

You are not perfect (neither are we). In fact, your lack of perfection is part of what makes you human. What does a perfect presentation look like? We wouldn’t know because we’ve never seen a perfect presentation. The best presentations are those presentations in which people are authentic and vulnerable. These presenters create real connections with their audiences because they themselves are being real. Let us repeat—the best presentations are those in which the speaker makes an authentic connection with the audience. Being yourself—flaws and all—is the secret to effective delivery style.

One great example of the imperfect but vulnerable delivery style is the (in)famous Monkey Boy speech by Steve Ballmer. Mr. Ballmer was CEO of Microsoft from 2000 to 2014 and is the current owner of the Los Angeles Clippers basketball team. If you ever want to see a truly authentic—if not unnerving—delivery style, Google “Steve Ballmer Monkey Boy.” He delivered the Monkey Boy speech while at Microsoft. It opens with him running and dancing around the stage screaming “Woo!” He then opened his presentation breathlessly with the words “I have four words for you! I love this company!” This is authentic Steve Ballmer. He has had similar displays of emotion in other presentations. He is comfortable with being emotional and vulnerable. At his final presentation before leaving Microsoft, he cried openly in front of the audience. Mr. Ballmer is an authentic and memorable speaker. His presentations are far from perfect, but they have impact!

Maybe running, dancing, screaming, and crying are not your thing. If not, then don’t act that way during your presentations. Be your authentic self. Have the bravery to make yourself vulnerable. Dr. Brené Brown is a social work professor who has dedicated her life to studying vulnerability and courage. She argues that being truly authentic means making yourself vulnerable. She wrote that “vulnerability sounds like truth and feels like courage. Truth and courage aren’t always comfortable, but they’re never weakness.”5 In addition to having great advice on the topic of vulnerability, she has an authentic delivery style. She is quiet and calm with a dry wit; but because she is authentic, she is still every bit as engaging as Mr. Ballmer.

In an impressive TEDx presentation on vulnerability, Dr. Brown gave excellent advice that applies not only to our approach to interpersonal relationships but also to engaging our audiences.6 She said that we all struggle with being authentic and making ourselves vulnerable to others. In our efforts to avoid vulnerability, she said that people try to perfect things. As she put it, “We take fat from our butts and put it in our cheeks.” And the result is a loss of authenticity. We believe that people do the same things with their presentations. In an effort to avoid the vulnerability associated with being authentic and making real connections, we focus our energy in the wrong places and try to perfect elements of our presentation (e.g., multimedia slides and individual words) while failing to pay attention to the fundamental need to simply connect. Dr. Brown also argued that we protect ourselves from vulnerability by pretending that what we do has no effect on others. The truth is we can’t make our presentations perfect, and what we do matters. Embracing the vulnerability of imperfection can be liberating. So, as Dr. Brown says, “Lean into the vulnerability.” An audience that connects with you and cares about you is always willing to forgive and overlook minor flaws.

Have a Conversation. Be Extemporaneous

One way to demonstrate authenticity is through an extemporaneous speaking style. This is a speaking style that allows you to use notes sparingly. Your audience will be bored to tears if you read from your notes. For the vast majority of us, reading sounds like reading. That’s boring. Reading from our notes also causes us to lose eye contact with our audience. It is difficult to have a conversation with a person with whom you are not making eye contact. Eye contact allows us to engage with our audience and see how they react to what we are saying. It gives us the opportunity to make changes (such as adding clarification if audience members look confused) during a presentation.

Your notes should be limited to key words, ideas, and statistics. They should also contain speaking cues, little reminders about your delivery style. For instance, if you tend to fall into the trap of looking at your notes too frequently, you can put on the note card in bold letters: STOP STARING AT ME.

While we are on the topic of note cards, we encourage you to use note cards that fit neatly in your hand. Avoid using half or whole sheets of paper. We tell our students that there are few visual cues that audience members can see to signal the speaker’s anxiety level. One of those cues is when the speaker’s hands are shaking. Hand shaking is much more noticeable when you’re holding a large sheet of paper in your hands.

Speak Loudly, Clearly, and With Conviction

So much of your message is carried by your voice. As Nancy Duarte puts it, “Your voice is multitalented.” It can make you sound assertive, cautious, critical, humorous, motivational, sympathetic, or neutral. In business presentations, people often purposefully use a dispassionate, flat voice.7 As we’ve said repeatedly throughout this book, emotions matter. A flat speaking voice does not make you sound objective; it makes you sound boring and dull. Use vocal variation by changing the pitch, rate, and tone of your voice to stress key points and create contrast. Practice your presentation and record those rehearsals when possible so that you can find and eliminate verbal fillers (e.g., “um”) and find places to use your voice for impact. We discuss practice more thoroughly in the following text.

Move

Whenever possible, get away from the lectern (or podium). Remove barriers between you and your audience. Physical barriers may make you feel more comfortable, but they create distance between you and your audience. Remember that you are trying to have an engaging conversation. If you doubt our advice about the lectern, then try this simple test. The next time you go on a date, place a lectern on the table between you and your date. Let us know how the conversation goes. Instead of hiding behind a lectern, move (see Figure 6.3).

Movement has a number of excellent benefits. Not only does movement bring you closer to your audience, it also gives your body’s nervous energy a healthy outlet. Nervous energy will find a way out. That’s why people do strange things such as swaying side to side like a tree in the breeze or playing with their jewelry. Movement can also help you keep your presentation organized. For example, if your presentation has three main points, then you can identify each supporting point with an object in the room. Walk over to the first object, place your hand on it, and talk about the point associated with that object. When you are done making the first point, move to the second object and discuss the second object. And so on.

Figure 6.3 Speaker using movement to reduce barriers between him and the audience

Dress Appropriately

We can’t tell you exactly how to dress for a presentation. You have to know your audience. If all else fails, a conservative business suit often works. Just remember that your appearance sends a message to your audience. Match your appearance to the audience and situation.

Practice the Right Way

We want you to stop worrying so much about being perfect in your delivery style. Does that mean you should skip all the practice? No. We want you to be authentic, not lazy. Audiences will overlook minor flaws; major flaws are another matter. You should practice. Practice will help you become more comfortable. You should, however, practice the right way. To learn the habits of good practice, we can learn from poor practice habits.

Some people never practice or never give themselves enough time to practice well. If you’re the person who never practices, stop it. You’re setting yourself up for failure. If you’re the person who only practices once or twice the night before (or morning of) a presentation, stop it. You need time to practice. If you learn from your practice that you need to make major changes, you need time to make those changes and to practice more. Not practicing is not only inconsiderate, but it is not virtuous.

Some people do practice and even give themselves enough time to do so. Unfortunately, they either “rehearse” the presentation in their head without actually saying anything (not good for delivery) or fail to have an audience for their practice. If your goal as a speaker is to be authentic and to connect with your audience, then practicing in a room all by yourself is not terribly productive.

Some people practice in front of an audience, but they choose the wrong audience. These people gather friends, family members, or colleagues who are willing to listen to the rehearsal presentation but are not truly willing to give critical feedback. These rehearsal audience members simply tell you things like “It sounds great!” Although that’s a nice boost to the ego, uncritical feedback does not help us to improve. In addition, when you have the wrong rehearsal audience, you take liberties that you wouldn’t otherwise take. For example, when you make a minor error in front of the wrong rehearsal audience, you may stop and explain why you made the mistake and how you will fix it in the future or you may stop the presentation and start all over again. We strongly believe that once you start a rehearsal, you should move from start to finish without stopping.

Remember that no presentation is perfect. So why hold yourself to that standard? Forcing yourself to go from beginning to end without stopping replicates what the actual presentation will be like. You might as well get used to working through your mistakes. When you make a mistake, take a mental note and try to improve the next time through.

Designing and Using Multimedia Slides

Love it or hate it, multimedia slide design software, such as PowerPoint, Keynote, and Prezi, has become a part of the business presentation experience. As we mentioned earlier in this book, we have all been the victims of “death by PowerPoint,” but we can’t blame the software. We must blame those who use the software, including ourselves. Poor design is the result of poor planning, poor work habits, and (excuse our language) laziness.

The good news is that you have the power to fix what’s wrong with your slide design. The better news is that you don’t have to be a designer to make beautiful slides that have the appropriate impact on your audience. In this chapter, we give you some tips that you can put into practice immediately that will make your slides better. The ultimate takeaway from these tips is that less is more! For a more thorough treatment of slide design, we strongly recommend the following resources:

Presentation Zen: Simple Ideas on Presentation Design and Delivery by Garr Reynolds

The Non-Designers Design Book by Robin Williams

Overcoming Poor Planning, Poor Work Habits, and Laziness

We have been asked thousands of questions about slide design over the years. The most common questions include:

How many bullet points are appropriate?

How many words should I put on my slides?

How many slides do I need to use?

The people who ask these questions are usually looking for concrete answers. Unfortunately, there are no simple answers. Slide design requires creative and critical thinking skills, and these skills require that you give yourself some time. We usually tell people that they should start by asking whether they need multimedia slides at all. Presenters often default to slides when they don’t need them. Our answers to the questions in the preceding text usually end up looking something like this (in bullet point form):

As many as you need to be clear, but not too many

As many as you need to be clear, but not too many

As many as you need to be clear, but not too many

How can it be that we live in a world where people hate bullet points and text-heavy slides and yet we are exposed to them almost daily? We do, in fact, have some simple answers to that question. First, people don’t allow enough time for appropriate slide design. Too often, they try to design slides while also writing their presentation. These are two separate processes and should be treated as such. We urge you to write the presentation first and then design your slides. Second, people rely on PowerPoint default settings to guide them through the process. Consider Figure 6.4 that follows.

This is what you see when you open PowerPoint. Those bullet points are already there for you, like tantalizingly beautiful sirens calling out to you with their siren song. It’s easy to simply fill in those bullets with words. Don’t do it. It’s a trap! Presentation shipwreck lies ahead.

How do you avoid falling into that trap? You should do what communication expert Garr Reynolds calls “planning analog.” When planning your slides, use your imagination. Draw the slides. If they could look exactly as you want them, what would they look like? You don’t have to be an artist. Our drawings feature stick figures. To guide you in the process, you can print out a series of blank slides as a handout from PowerPoint. What you get are beautifully blank squares (see Figure 6.5) into which you can draw whatever content you like. Once you’re satisfied with what you’ve drawn, open your slide design software and try to force it to create what you’ve drawn. This helps you avoid simply following the defaults.

Figure 6.4 Default PowerPoint slide

Audiences also tend to dislike the overuse of SmartArt graphics, clip art, and background templates. They have become cliché, and they make you look like an unseasoned amateur. Instead, we encourage you to get creative and resourceful. Use high-quality pictures and images. You can take your own pictures or use one of the many resources online to find free or very low-cost stock photos.

It is important to remember that you are the presentation. The multimedia slides are there to evoke an emotional response from your audience and to support your message. The slides are not the message. Avoid overusing text and do not read from your slides! If you find that you must provide your audience with detailed information, lots of text, and tables crammed with data, then you need to produce a handout. Don’t force the content onto your multimedia slides. Remember that your audience can only retain so much information and can pay attention to only so many stimuli. If they are busy reading your slides, they will not be listening to you.

Figure 6.5 Blank PowerPoint slides for your planning

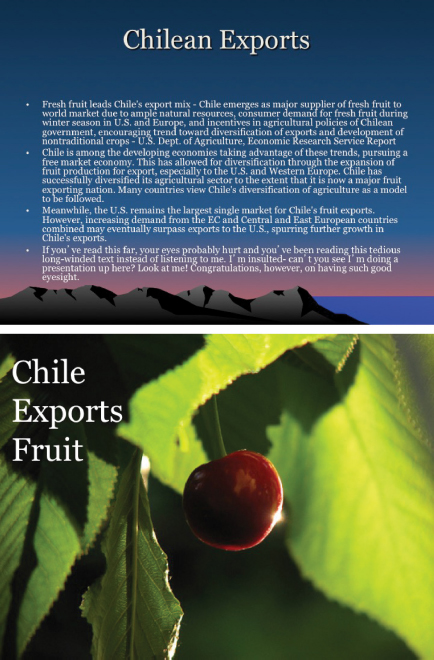

The slide on the top side of Figure 6.6 was used in an actual presentation. It contains too many words. It uses a generic, clichéd background that has little to do with the topic of the presentation. It fails to make an emotional connection. Compare that to the slide on the bottom side of Figure 6.6. Do you see the difference?

Figure 6.6 A slide that fails to evoke an emotional response and one that does8

Presenting with data can be tricky. We encourage—nay, demand—you to remember the less is more principle. When using data in your slides, carefully consider the point you are making with your data and present only enough data points to make that point. Any data that exceeds that threshold is just noise. It can actually distract from your point.

Consider the slide in Figure 6.7. Jason captured a picture of this slide during a presentation at our university. First, the slide displays so much data that it is nearly impossible to read. In fact, the speaker apologized for the small font. This happens frequently. Presenters produce poor slides and then apologize to the audience members.

Instead of making your audience members suffer through poorly produced slides, fix or eliminate them. When presenting with data, you have to consider font size. The data is useless if the audience can’t see it.

You also need to consider what and how much data to present. The point of the slide in Figure 6.7 was that 54 students were within 30 credits of graduating and for some reason they left the university. Did all of that data really need to be presented in a slide? It is too much data and the font is too small. The data also doesn’t do much to support the major point. In this case, the slide would look much better if it were converted to a handout. Jason snapped this picture because he realized that he was spending a great deal of time trying to read the slide and missed the point. He had to watch a video of the presentation to get the point.

Figure 6.7 Multimedia slide with too much data

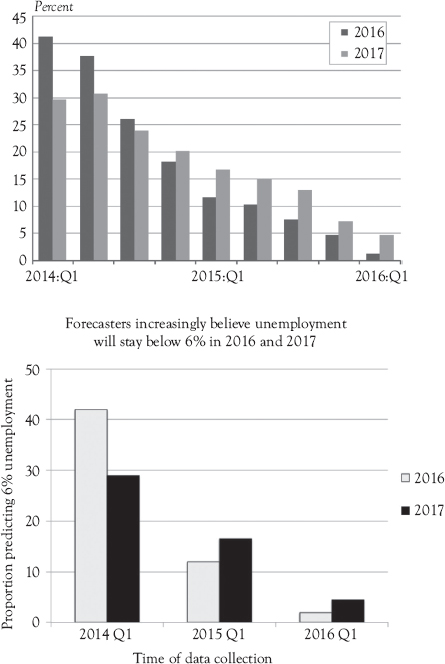

Another thing to consider when presenting with data is that you want your audience to be able to look at the data in a slide and very quickly draw the appropriate conclusion. The longer they think about the data, the less able they are to pay attention to what you have to say. Consider the slide in Figure 6.8 that follows.

Lisa snapped a picture of this slide about interest rates and the health of the economy. The presentation was interesting and intellectually engaging. The slides were, however, one notable exception. Look at the slide for five seconds. What’s the point? Now imagine that you’re trying to figure that out while a speaker is talking. Your odds of processing both the data and the content of the presentation are low. It’s likely that this figure was copied from a written report without being reformatted for a presentation.

The slide on the top side of Figure 6.9 was another of Lisa’s snapshots from the same presentation. The title of the slide does not make the point clear.

The vertical axis has too many major data points. The horizontal axis contains too many data points. This relatively good slide could be even better if left in the hands of a virtuous presenter. Compare the slide on the top side of Figure 6.9 with the one on the bottom side. Do you see how a few minor changes make the same data much clearer? Even though the slides contains fewer data points, you see a fairly clear linear trend in the data. In addition, the slide’s title does a better job of conveying the slide’s meaning.

Figure 6.8 Sample slide where the point is not immediately clear9

Figure 6.9 A “good” slide and a “virtuous” slide10

Conclusion

In this, the book’s final chapter, we provided you with a number of tips for becoming a “virtuous presenter.” In particular, you should now know how to organize content for best results, develop an effective call to action, deliver with confidence, and build multimedia slides that won’t bore your audience (see Box 6.4). Above all else, please remember that you are the presentation. As a finance professional, you are only asked to deliver a presentation because people in charge believe you know something that they do not. You are being given an opportunity. Don’t squander that opportunity. Be bold and deliver a presentation that has real impact. Be a virtuous presenter.

Box 6.4 Chapter 6 takeaways

Be virtuous—Exhibit fortitude, prudence, justice, and temperance.

Capture the audience’s attention—Even when you’re an invited speaker, the audience may be distracted.

Organize for impact—Your audience can retain only so much information. So what do you want them to remember?

Call your audience to action—Make taking action easy for your audience.

Deliver with confidence—Be yourself. That advice is as good for presentations as it is for dating. Remember that you know what you’re talking about. Your delivery will be enhanced if you practice the right way.

Design multimedia slides that get the job done—Go analog and try to make the slides look the way you want them to. The software should not tell you what to do. Tell the software what to do.