1

Welcome to the Experience Economy

Commoditized. No company wants that word applied to its goods or services. Merely mentioning commoditization sends shivers down the spines of executives and entrepreneurs alike. Differentiation disappears, margins fall through the floor, and customers buy solely on the basis of price, price, price.

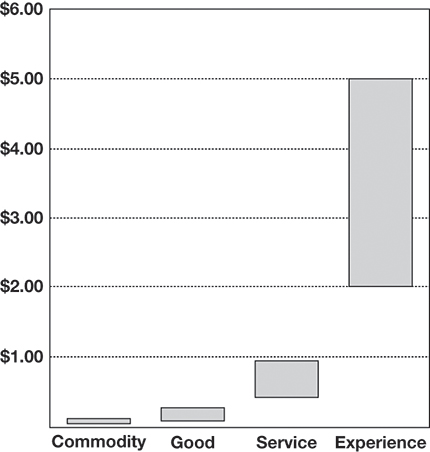

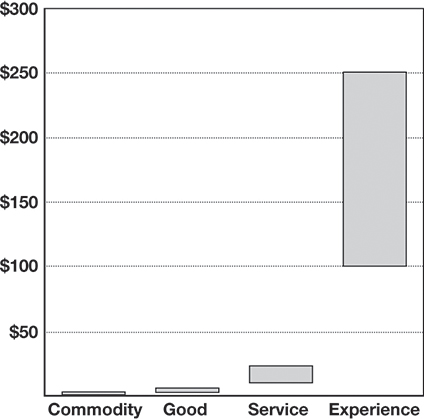

Consider, however, a true commodity: the coffee bean. Companies that harvest coffee or trade it on the futures market receive—at the time of this writing—a little more than 75 cents per pound, which translates into 1 or 2 cents a cup. When a manufacturer roasts, grinds, packages, and sells those same beans in a grocery store, turning them into a good, the price to a consumer jumps to between 5 and 25 cents a cup (depending on brand and package size). Brew the ground beans in a run-of-the-mill diner, quick-serve restaurant, or bodega, and that coffee-making service now sells for 50 cents to a dollar or so per cup.

So depending on what a business does with it, coffee can be any of three economic offerings—commodity, good, or service—with three distinct ranges of value customers attach to the offering. But wait: serve that same coffee in a five-star restaurant or a cafe such as Starbucks—where the ordering, creation, and consumption of the cup embody a heightened ambience or sense of theatre—and consumers gladly pay $2 to $5 a cup. Businesses that ascend to this fourth level of value (see figure 1-1) establish a distinctive experience that envelops the purchase of coffee, increasing its value (and therefore its price) by two orders of magnitude over the original commodity.

FIGURE 1-1

Price of coffee offerings

Or more. Immediately upon arriving in Venice, a friend of ours asked a hotel concierge where he and his wife could go to enjoy the city’s best. Without hesitation he directed them to the Caffè Florian in St. Mark’s Square. The two of them were soon at the cafe in the crisp morning air, sipping cups of steaming coffee, fully immersed in the sights and sounds of the most remarkable of Old World cities. More than an hour later, our friend received the bill and discovered the experience had cost more than $15 a cup. “Was the coffee worth it?” we asked. “Assolutamente!”

A New Source of Value

Experiences are a fourth economic offering, as distinct from services as services are from goods, but one that has until now gone largely unrecognized. Experiences have always been around, but consumers, businesses, and economists lumped them into the service sector along with such uneventful activities as dry cleaning, auto repair, wholesale distribution, and telephone access. When a person buys a service, he purchases a set of intangible activities carried out on his behalf. But when he buys an experience, he pays to spend time enjoying a series of memorable events that a company stages—as in a theatrical play—to engage him in an inherently personal way.

Experiences have always been at the heart of entertainment offerings, from plays and concerts to movies and TV shows. Over the past few decades, however, the number of entertainment options has exploded to encompass many, many new experiences. We trace the beginnings of this experience expansion to one man and the company he founded: Walt Disney. After making his name by continually layering new levels of experiential effects on to cartoons (he innovated synchronized sound, color animation, three-dimensional backgrounds, stereophonic sound, audio-animatronics, and so forth), Disney capped his career in 1955 by opening Disneyland—a living, immersive cartoon world—in California. Before his death in 1966, Disney had also envisioned Walt Disney World, which opened in Florida in 1971. Rather than create another amusement park, Disney created the world’s first theme parks, which immerse guests (never “customers” or “clients”) in rides that not only entertain but also involve them in an unfolding story. For every guest, cast members (never “employees”) stage a complete production of sights, sounds, tastes, aromas, and textures to create a unique experience.1 Today, The Walt Disney Company carries on its founder’s heritage by continually “imagineering” new offerings to apply its experiential expertise, from TV shows on the Disney Channel to “character worlds” at Disney.com, from Broadway shows to the Disney Cruise Line, complete with its own Caribbean island.

Whereas Disney used to be the only theme park proprietor, it now faces scores of competitors in every line of business, both traditional and experimental. New technologies encourage whole new genres of experience, such as video games, online games, motion-based attractions, 3-D movies, virtual worlds, and augmented reality. Desire for ever greater processing power to render ever more immersive experiences drives demand for the goods and services of the computer industry. Former Intel chairman (now senior adviser) Andrew Grove anticipated the explosion of technology-enabled offerings in a mid-1990s speech at the COMDEX computer show (itself an experience), when he declared, “We need to look at our business as more than simply the building and selling of personal computers [that is, goods]. Our business is the delivery of information [that is, services] and lifelike interactive experiences.” Exactly.

Many traditional service industries, now competing for the same dollar with these new experiences, are themselves becoming more experiential. At theme restaurants such as Benihana, the Hard Rock Cafe, Ed Debevic’s, Joe’s Crab Shack, and the Bubba Gump Shrimp Co., the food functions as a prop for what’s known in the industry as an “eatertainment” experience. And stores such as Build-A-Bear Workshop, Jordan’s Furniture, and Niketown draw consumers through fun activities and promotional events (sometimes called “entertailing,” or what The Mills Corp. trademarked as “shoppertainment”).

But this doesn’t mean that experiences rely exclusively on entertainment; as we explain fully in chapter 2, entertainment is only one aspect of an experience. Rather, companies stage an experience whenever they engage customers, connecting with them in a personal, memorable way. Many dining experiences have less to do with the entertainment motif than with the merging of dining with comedy, art, history, or nature, as happens at such restaurants as Teatro ZinZanni, Café Ti Tu Tango, Medieval Times, and the Rainforest Cafe, respectively.2 In each place, the food service provides a stage for layering on a larger feast of sensations that resonate with consumers. Retailers such as Jungle Jim’s International Market, The Home Depot, and the Viking Cooking School offer tours, workshops, and classes that combine shopping and education in ways that we can rightly describe as “edutailing” or “shopperscapism.”

The “commodity mindset,” according to former British Airways chairman Sir Colin Marshall, means mistakenly thinking “that a business is merely performing a function—in our case, transporting people from point A to point B on time and at the lowest possible price.” What British Airways does, he continued, “is to go beyond the function and compete on the basis of providing an experience.”3 The company uses its base service (the travel itself ) as a stage for a distinctive en route experience, one that gives the traveler a respite from the inevitable stress and strain of a long trip.

Even the most mundane transactions can be turned into memorable experiences. Standard Parking of Chicago plays a signature song on each level of its parking garage at O’Hare Airport and decorates walls with icons of a local sports franchise—the Bulls on one floor, the Blackhawks on another, and so forth. As one Chicago resident told us, “You never forget where you parked!” Trips to the grocery store, often a burden for families, become exciting events at places such as Bristol Farms Gourmet Specialty Foods Markets in Southern California. This upscale chain “operates its stores as if they were theatres,” according to Stores magazine, featuring “music, live entertainment, exotic scenery, free refreshments, a video-equipped amphitheater, famous-name guest stars and full audience participation.”4 Russell Vernon, owner of West Point Market in Akron, Ohio—where fresh flowers decorate the aisles, restrooms feature original artwork, and classical music wafts down the aisles—describes his store as “a stage for the products we sell. Our ceiling heights, lighting and color create a theatrical shopping environment.”5 Grocers such as The Fresh Market and Whole Foods Markets replicate these local food experiences and scale them on a regional and national basis, respectively.

Consumers aren’t the only ones to appreciate such experiences. Businesses are made up of people, and business-to-business settings also present stages for experiences. A Minneapolis-based computer installation and repair firm first dubbed itself the Geek Squad in 1994 and began focusing on home-office and small business customers. With its special agents costumed in white shirts with thin black ties, carrying badges, and driving black-and-white Beetles, called Geekmobiles, painted like squad cars, the company turns mundane services into truly memorable encounters. Today the “24-Hour Computer Support Task Force” employs more than twenty-four thousand agents as part of Best Buy. Costumed entrepreneurs in other industries followed suit, such as a garbage collector calling itself the Junk Squad (“Satisfaction Guaranteed or Double Your Junk Back”). Many companies hire theatre troupes to turn otherwise ordinary meetings into improvisational events. Minneapolis-based LiveSpark (formerly Interactive Personalities, Inc.), for example, stages rehearsed plays and “spontaneous scenes” for corporate customers, engaging audience members in a variety of ways, including computer-generated characters that interact in real time.6

Business-to-business marketers increasingly orchestrate events at elaborate venues to pitch prospects. Scores of B2B companies turn mundane conference rooms into experiential “executive briefing centers”—and some go beyond that, such as Johnson Controls’ Showcase in Milwaukee, where the company plunges business guests into a power outage to show off its products in action. Steelcase recently launched a venue called WorkSpring, the first one in Chicago, offering unique office space so that corporate guests experience furniture in actual meetings before making purchasing decisions. TST, Inc., an engineering firm in Fort Collins, Colorado, gutted its office to create the TST Engineerium, a place for staff to host “visioneering experiences” for its land development customers. Autodesk, Inc., developers of engineering and design software, curates the Autodesk Gallery at One Market in San Francisco as a place to showcase clients’ use of its technology in innovative design projects (and opens the B2B interactive art exhibition to the general public every Wednesday afternoon). One B2B experience takes place outdoors: the Case Tomahawk Customer Experience Center in the Northwoods of Wisconsin. Prospective buyers play in a giant sandbox with large construction equipment—bulldozers, backhoes, cherry pickers, and the like—as part of the selling process.

Valuable Distinctions

The foregoing examples—from consumer to business customer, theme restaurant to computer support task force—only hint at the newfound prominence of such experiences within the U.S. economy and, increasingly, those of other developed nations as well. They herald the still emerging Experience Economy.

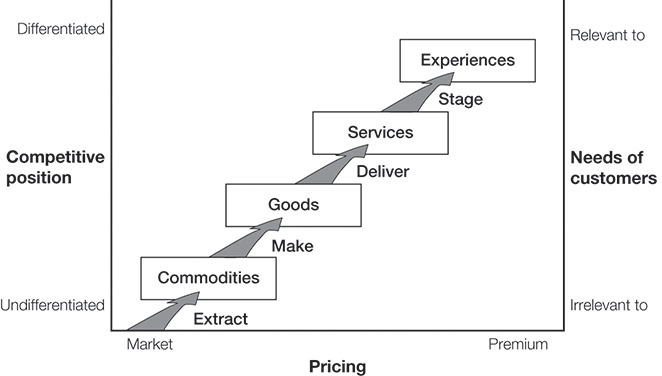

Why now? Part of the answer lies with technology, which powers many experiences, and part with increasing competitive intensity, which drives the ongoing search for differentiation. But the most encompassing answer resides in the nature of economic value and its natural progression—like that of the coffee bean—from commodity to good to service and then to experience. An additional reason for the rise of the Experience Economy is, of course, rising affluence over time. Economist Tibor Scitovsky notes that “man’s main response to increasing affluence seems to be an increase in the frequency of festive meals; he adds to the number of special occasions and holidays considered worthy of them and, ultimately, he makes them routine—in the form, say, of Sunday dinners.”7 The same is true of experiences we pay for. We are going out to eat more frequently at increasingly experiential venues, and even drinking “festive” types of coffee. As summarized in table 1-1, each economic offering differs from the others in fundamental ways, including just what, exactly, it is. These distinctions demonstrate how each successive offering creates greater economic value. Often a manager claims a company is “in a commodity business” when in fact the offering sold is not a true commodity. The perception results in part from a self-fulfilling commoditization that occurs whenever an organization fails to fully recognize the distinctions between higher-value offerings and pure commodities. (And if an analyst or pundit says your company sells a commodity when you don’t, you have been insulted, as well as challenged to shift up to a higher level in economic value.) If you fear that your offerings are being commoditized, read the simple descriptions given next. And if you think your offerings could never be commoditized—think again. A haughty spirit goes before a great fall (in prices).

Economic distinctions

| Economic offering | Commodities | Goods | Services | Experiences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economy | Agrarian | Industrial | Service | Experience |

| Economic function | Extract | Make | Deliver | Stage |

| Nature of offering | Fungible | Tangible | Intangible | Memorable |

| Key attribute | Natural | Standardized | Customized | Personal |

| Method of supply | Stored in bulk | Inventoried after production | Delivered on demand | Revealed over a duration |

| Seller | Trader | Manufacturer | Provider | Stager |

| Buyer | Market | User | Client | Guest |

| Factors of demand | Characteristics | Features | Benefits | Sensations |

Commodities

True commodities are materials extracted from the natural world: animal, mineral, vegetable. People raise them on the ground, dig for them under the ground, or grow them in the ground. After slaughtering, mining, or harvesting the commodity, companies generally process or refine it to yield certain characteristics and then store it in bulk before transporting it to market. By definition, commodities are fungible—they are what they are and therefore interchangeable. Because commodities cannot be differentiated, commodity traders sell them largely into nameless markets where a company purchases them for a price determined by supply and demand. (Companies do of course supply gradations in categories of commodities, such as different varieties of coffee beans or different grades of oil, but within each grade the commodity is purely fungible.) Every commodity trader commands the same price as everyone else selling the same stuff, and when demand greatly exceeds supply, handsome profits ensue. When supply outstrips demand, however, profits prove hard to come by. Over the short term, the cost of extracting the commodity bears no relationship to its price, and over the long term the invisible hand of the market determines the price as it encourages companies to move in or out of commodity businesses.

Agricultural commodities formed the basis of the Agrarian Economy, which for millennia provided subsistence for families and small communities. When the United States was founded in 1776, more than 90 percent of the employed population worked on farms. In 2009, that number had dropped to 1.3 percent.8

What happened? The tremendous technological and productivity improvements that became known as the Industrial Revolution drastically altered this way of life, beginning on the farm but quickly extending into the factory (such as the pin-making factory made famous by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations, published, coincidentally, in 1776). Building on the success of companies in England from the 1750s onward, flourishing U.S. factories developed their own production innovations that in the 1850s collectively became known as the American System of Manufactures.9 As manufacturers the world over learned and copied these techniques, automating millions of craft jobs in the process, the foundation for all advanced economies irrevocably shifted to goods as farm employment plummeted.

Goods

Using commodities as their raw materials, companies make and then inventory goods—tangible items sold to largely anonymous customers who buy them off the shelf, from the lot, out of the catalog, or on the Web. Because manufacturing processes actually convert the raw materials in making a variety of goods, leeway exists to set prices based on the costs of production as well as product differentiation. Significant differences exist in the features of various makes of automobiles, computers, soft drinks, and, to some degree, even lowly pins. And because they can be put to immediate use—to get places, write reports, quench thirsts, fasten things together—their users value them more highly than the commodities from whence they came.

Although people have turned commodities into useful goods throughout history, the time-intensive means of extracting commodities and the high-cost methods of craft-producing goods long prevented manufacturing from dominating the economy.10 This changed when companies learned to standardize goods and gain economies of scale. People left the farm in droves to work in factories, and by the 1880s the United States had overtaken England as the world’s leading manufacturer.11 With the advent of Mass Production, brought about in the first assembly line at Henry Ford’s Highland Park, Michigan, plant on April 1, 1913, the United States solidified its position as the number one economic power in the world.12

As continued process innovations gradually reduced the number of workers required to produce a given output, the need for manufacturing workers leveled off and eventually began to decline. Simultaneously, the vast wealth generated by the manufacturing sector, as well as the sheer number of physical goods accumulated, drove a greatly increased demand for services and, as a result, service workers. It was in the 1950s, when services first employed more than 50 percent of the U.S. population, that the Service Economy overtook the Industrial (although this was not recognized until long after the fact). In 2009, manufacturing jobs—people actually making things with their hands—employed a mere 10 percent of the working population.13 With farming employing 1.3 percent, what economists today categorize as services makes up almost 90 percent of U.S. workers. Globally, service jobs recently eclipsed agricultural ones for the first time in human history: some 42 percent of worldwide workers find employment in the service sector, 36 percent in agriculture, and only 22 percent in manufacturing.14 (Of course, these statistics, from the United Nations International Labour Organization, fail to distinguish those working in experience-staging employment; so the service sector figure includes experience-staging jobs as well.)

Services

Services are intangible activities customized to the individual request of known clients. Service providers use goods to perform operations on a particular client (such as haircuts or eye exams) or on his property or possessions (such as lawn care or computer repair). Clients generally value the benefits of services more highly than the goods required to provide them. Services accomplish specific tasks clients want done but do not want to do themselves; goods merely supply the means.

Just as gray areas lie between commodities and goods (extensive processing or refining may merge into making), the line between goods and services can be blurry. Even though restaurants deliver tangible food, for example, economists place them in the service sector because they do not inventory their offerings but deliver them on demand in response to an individual patron’s order. Although fast-food restaurants that make the food in advance share fewer of these attributes and so lie closer to the realm of goods than others, economists rightly count those employed at McDonald’s, for instance, in the service sector.

While employment continues to shift to services, output in the commodity and goods sectors has not abated. Today, fewer farmers harvest far more than their ancestors ever conceived possible, and the sheer quantity of goods rolling off assembly lines would shock even Adam Smith. Thanks to continued technological and operational innovations, extracting commodities from the ground and making goods in factories simply require a diminishing number of people. Still, the percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) devoted to the service sector today dwarfs the other offerings. After fearing for many years the hollowing of the U.S. industrial base, most pundits now recognize it as a positive development that the United States, along with most advanced countries, has shifted full-bore to a Service Economy.

With this shift comes another little-realized or -discussed dynamic: In a Service Economy, individuals desire service. Whether consumers or businesses, they scrimp and save on goods (buying at Walmart, squeezing suppliers) in order to purchase services (eating out, managing the company cafeteria) they value more highly. That’s precisely why many manufacturers today find their goods commoditized. In a Service Economy, the lack of differentiation in customers’ minds causes goods to face the constant price pressure indelibly associated with commodities. As a result, customers more and more purchase goods solely on price and availability.

To escape this commoditization trap, manufacturers often deliver services wrapped around their core goods. This provides fuller, more complete economic offerings that better meet customer desires.15 So automakers, for example, increase the coverage and length of their warranties while financing and leasing cars, consumer goods manufacturers manage inventory for grocery stores, and so forth. Initially, manufacturers tend to give away these services to better sell their goods. Many later realize that customers value the services so highly that the companies can charge separately for them. Eventually, astute manufacturers shift away from a goods mentality to become predominantly service providers.

Look at IBM. In its heyday in the 1960s and 1970s the hardware manufacturer’s well-earned slogan was “IBM Means Service,” as it lavished services—at no cost—on any company that would buy its hardware goods. It planned facilities, programmed code, integrated other companies’ equipment, and repaired its own machines so prodigiously as to overwhelm nearly all competitors. But as time went on and the industry matured, customer demand for service (not to mention the Justice Department suit that forced IBM to unbundle its hardware and software) surpassed the company’s ability to give it away, and it began to charge explicitly for its services. Company executives eventually discovered that the services it once provided for free were, in fact, its most valued offerings. Today, with its mainframe computers long since commoditized, IBM’s Global Services unit grows at double-digit rates. The company no longer gives away its services to sell its goods. Indeed, the deal is reversed: IBM buys its clients’ hardware when they contract with Global Services to manage their information systems. IBM still manufactures computers, but it’s now in the business of providing services.

Buying goods to sell services—or at least giving them away below cost or for nothing, as mobile phone operators do—signifies that the Service Economy has reached a level once thought unimaginable and, by many, undesirable. Not very long ago academics and pundits still decried the takeover by services as the engine of economic growth, asserting that no economic power could afford to lose its industrial base and that an economy based overwhelmingly on services would become transient, destined to lose its prowess and its place among nations. That concern is now obviously unfounded. In fact, only the shift to services allowed for continued prosperity in the face of the ever-increasing automation of commoditized goods.

The dynamic continues. The commoditization trap that forced manufacturers to add services to the mix now attacks services with a similar vengeance. Telephone companies sell long-distance service solely on price, price, price. Airplanes resemble cattle cars, with a significant number of passengers flying on free awards; in a last-ditch effort, airlines consolidate, and nickel-and-dime customers for ancillary services, to maintain profitability. Fast-food restaurants all stress “value” pricing; few have managed to avoid offering a “dollar menu.” (Interestingly, the Economist created the Big Mac Index to compare the price levels in different countries based on the price of a local Big Mac.16 Perhaps a new metric should measure the number of items now available for a mere buck.) And price wars abound in the financial services industry as first discount and then Internet-based brokers constantly drive down commissions, charging as little as $3 for what a full-service broker would charge more than $100. J. Joseph Ricketts, founder of Ameritrade, even told BusinessWeek, “I can see a time when, for a customer with a certain size margin account, we won’t charge commissions. We might even pay a customer, on a per trade basis, to bring the account to us.”17 An absurdity? Only if one fails to recognize that any shift up to a new, higher-value offering entails giving away the old, lower-value offering.

Indeed, the Internet is the greatest known force of commoditization for goods as well as services. It eliminates much of the human element in traditional buying and selling. Its capability for friction-free transactions enables instant price comparisons across myriad sources. And its ability to quickly execute these transactions allows customers to benefit from time as well as cost savings. With time-starved consumers and speed-obsessed businesses, the Internet increasingly turns transactions for goods and services into a virtual commodity pit.18 Web-based enterprises busy commoditizing both consumer and business-to-business industries include specialty commoditizers—such as CarsDirect.com (automobiles), compare.net (consumer electronics), getsmart.com (financial services), insweb.com (insurance), and priceline.com (airline travel)—and general commoditizers that help buyers find lower prices for virtually all goods and services, such as bizrate.com, netmarket.com, NexTag.com, pricegrabber.com, and mySimon.com, to name a few. Consider, too, the ease with which consumers can perform such commoditizing tasks as finding used books via Amazon.com or searching for items via Google. And of course newspaper classified ads, the once dominant means for price-conscious consumers to find low-cost secondhand items, now have unprecedented competition from the commoditizing presence of eBay and CraigsList.

The other great force of commoditization? Walmart. That is the $400 billion behemoth’s entire modus operandi, accomplished by squeezing its suppliers, increasing its package sizes, enhancing its logistics—whatever it takes to lower the costs of the goods it sells. Note, too, that Walmart increasingly sells services, beginning with food and photographic services but now encompassing optometric, financial, and healthcare services and becoming a force for commoditization in that sector as well.

Service providers also face another adverse trend unknown to goods manufacturers: disintermediation. Companies such as Dell, USAA, and Southwest Airlines generally sidestep retailers, distributors, and agents to connect directly with their end buyers. Decreased employment in these intermediaries, as well as bankruptcies and consolidations, invariably results. And a third trend further curtails service sector employment: that old boogeyman automation, which today hits many service jobs (telephone operators, bank clerks, and the like) with the same force and intensity that technological progress hit employment in the goods sector during the twentieth century. Even professional service providers increasingly discover that their offerings have been “productized”—embedded into software, such as tax preparation programs.19 Or they have been offshored to India, as with manufacturing moving to China, in what amounts to a fourth force of commoditization.

All this points to an inevitable conclusion: the Service Economy has peaked. A new economy has arisen to increase revenues and create new jobs, one based on a distinct kind of economic output. Goods and services are no longer enough.

Experiences

Experiences have necessarily emerged to create new value. Such experience offerings occur whenever a company intentionally uses services as the stage and goods as props to engage an individual. Whereas commodities are fungible, goods tangible, and services intangible, experiences are memorable. Buyers of experiences—we’ll follow Disney’s lead and call them guests—value being engaged by what the company reveals over a duration of time. Just as people have cut back on goods to spend more money on services, now they also scrutinize the time and money they spend on services to make way for more memorable—and more highly valued—experiences.

The company—we’ll call it an experience stager—no longer offers goods or services alone but the resulting experience, rich with sensations, created within each customer. All prior economic offerings remain at arm’s length, outside the buyer, but experiences are inherently personal. They actually occur within any individual who has been engaged on an emotional, physical, intellectual, or even spiritual level. The result? No two people can have the same experience—period. Each experience derives from the interaction between the staged event and the individual’s prior state of mind and being.

Even so, some observers might argue that experiences are only a subclass of services, merely the latest twist to get people to buy certain services. Interestingly, the esteemed Adam Smith made the same argument about the relationship between goods and services more than two hundred years ago in The Wealth of Nations. He regarded services almost as a necessary evil—what he called “unproductive labour”—and not as an economic offering in itself, precisely because services cannot be physically inventoried and therefore create no tangible testament that work has been done. Smith did not limit his view of unproductive activity to such workers as household servants. He included the “sovereign” and other “servants of the public,” the “protection, security, and defence of the commonwealth,” and a number of professionals (“churchmen, lawyers, physicians, men of letters of all kinds”) whose efforts the current market has determined to be of far more value than that of most laborers. Smith then singled out the experience stagers of his day (“players, buffoons, musicians, opera-singers, opera-dancers, &c.”) and concluded, “The labour of the meanest of these has a certain value, regulated by the very same principles which regulate that of every other sort of labour; and that of the noblest and most useful, produces nothing which could afterwards purchase or procure an equal quantity of labour. Like the declamation of the actor, the harangue of the orator, or the tune of the musician, the work of all of them perishes in the very instant of its production.”20 However, even though the work of the experience stager perishes with its performance (precisely the right word), the value of the experience lingers in the memory of any individual who was engaged by the event.21 Most parents do not take their kids to Walt Disney World only for the venue itself but rather to make the shared experience part of everyday family conversations for months, or years, afterward.

Although experiences themselves lack tangibility, people greatly desire them because the value of experiences lies within them, where it remains long afterward. That’s why the studies performed by Cornell psychology professors Travis Carter and Thomas Gilovich determined that buying experiences makes people happier, with a greater sense of well-being, than purchasing goods.22 Similarly, the Economist summarized recent economic research into happiness as “‘experiences’ over commodities, pastimes over knickknacks, doing over having.”23

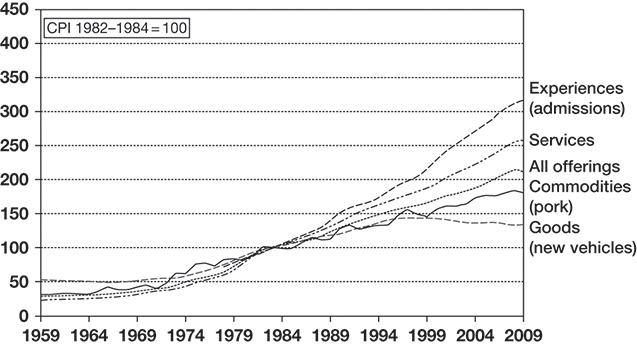

Companies that create such happiness-generating experiences not only earn a place in the hearts of consumers but also capture their hard-earned dollars—and harder-earned time. The notion of inflation as purely the result of companies passing along increased costs is not valid; higher prices also indicate greater value, especially in the way people spend their time. The shift in consumer (and business) demand from commodities to goods to services and now to experiences shifts the prototypical “market basket” to these higher-valued offerings—more than government statisticians take into account, we believe. In 2009, barely 60 percent of the total Consumer Price Index (CPI) was in services, which weren’t even included in the Producer Price Index until 1995.24 But if we examine the CPI statistics, as shown in figure 1-2, we see that the CPI for goods (using new vehicles, the prototypical Industrial Economy product) increases less than the CPI for services, which in turn increases less than the CPI for the one prototypical experience that can be found in the statistics: admissions to recreational events such as movies, concerts, and sports, which the government began tracking separately only in 1978.25 Note, too, the volatility of the CPI for a typical commodity, pork, relative to the other offerings. Increased price volatility as pure market forces take over awaits the sellers of all commoditized goods and services.26 (Pork actually surpasses new vehicles in these statistics because of not only its own volatility but also the increasing price pressure on the commoditizing automobile industry over the past decade or two while it simultaneously increased quality, which the government discounts in any price increases. We suspect these lines will once again cross.) Companies that stage experiences, on the other hand, increase the price of their offerings much faster than the rate of inflation because consumers value experiences more highly.

FIGURE 1-2

Consumer Price Index (CPI) by economic offering

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; Lee S. Kaplan, Lee3Consultants.com

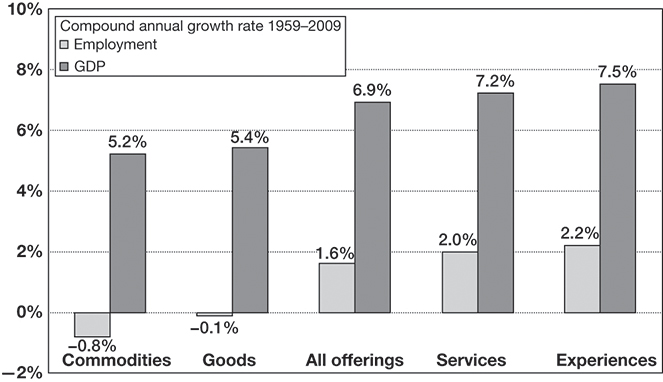

The employment and nominal GDP statistics show the same effect as the CPI, as figure 1-3 makes clear.27 In the fifty-year period 1959–2009, commodity output produced in the United States increased by a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.2%, while employment in commodity industries actually decreased. Manufacturing output increased only slightly more than commodity output, while also losing jobs on average every year, albeit only slightly (although the relative number of people employed in the manufacturing sector decreased greatly in the past fifty years). Services overpowered these sectors with a 2.0 percent CAGR in employment and more than 7 percent in GDP. But those industries (or portions) that could be pulled out of the government’s service sector statistics as experiential grew even faster: 2.2 percent employment and 7.5 percent GDP.28

FIGURE 1-3

Growth in employment and nominal gross domestic product (GDP) by economic offering

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis; Strategic Horizons LLP; and Lee S. Kaplan, Lee3Consultants.com analysis.

No wonder many companies today wrap experiences around their existing goods and services to differentiate their offerings. Service providers may have an edge in this regard, because they are not wedded to tangible offerings. They can enhance the environment in which clients purchase or receive the service, layer on inviting sensations encountered while in that company-controlled environment, and otherwise figure out how to better engage clients to turn the service into a memorable event.

Ing the Thing

What’s a manufacturer to do? Short of leapfrogging into the experience business—quite a stretch for most diehard manufacturers—manufacturers must focus on the experience customers have while using their goods.29 Most product designers focus primarily on the internal mechanics of the good itself: what it does. What if the attention centered instead on the individual’s use of the good? The focus would then shift to the user: how the individual experiences the using of the good.

Notice, for example, the diverse set of experiences highlighted in a travel guide from Fodor’s Travel Publications, an “escapist scrapbook” featuring the photography and essays of Peter Guttman. In Adventures to Imagine, Guttman documents twenty-eight adventures in which potential travelers can immerse themselves. Consider the range of activities—some old, some new, but all engaging: houseboating, portaging, mountain biking, cattle driving, bobsledding, tall ship sailing, tornado chasing, canyoneering, wagon training, seal viewing, iceberg tracking, puffin birding, race car driving, hot-air ballooning, rock climbing, spelunking, white-water rafting, canoeing, heli-hiking, hut-to-hut hiking, whale kissing, llama trekking, barnstorming, land yachting, historic battle reenacting, iceboating, polar bearing, and dogsledding.30 Companies constantly introduce new ing experiences to the outdoor adventure world. Just to add a few to the list: cross-golfing and guerilla-golfing (golfing without a golf course, playing instead in undeveloped rural terrains or abandoned urban settings, respectively), noboarding (snowboarding on boards that lack bindings), canyoning (bodysurfing in rapid mountain streams, usually in Switzerland or New Zealand) or riverboarding (with more protective gear in larger rapids), and glacier-walking (in places like Norway).

Retailers like Bass Pro Shops Outdoor World, Recreational Equipment, Inc. (REI), and Cabela’s sell goods as equipment for use in these types of experiences, and they lead the way in making their retail space an experience itself. Bass Pro Shops brings the outdoor environment indoors, REI provides a fifty-five-foot mountain in many stores so that customers can test its climbing gear, and Cabela’s displays a thirty-five-foot dioramic mountain filled with taxidermist-stuffed wild animals. Manufacturers, too, must explicitly design their goods to enhance the user’s experience—essentially experientializing the goods—even when customers pursue less-adventurous activities. Automakers do this when they focus on enhancing the driving experience, but they must also focus on other non-driving experiences that occur in cars. For example, many women are still waiting for a carmaker to accommodate purse storing in their vehicles. And certainly in-car dining could be enhanced for the millions who daily buy fast food via drive-through lanes.

Executives in the appliance industry already think this way. Former Maytag executive William Beer once told Industry Week, “The eating experience is now wherever a person is at the moment. We have people eating in the car on the way back and forth to work, in front of the TV.” This leads Beer to deduce that “people may need a refrigerated compartment in an automobile or in the arm of a chair,” innovations that would greatly enhance various eating occasions but would never surface within the framework of the industry’s old mindset, which focused on how appliances perform rather than on what users do when eating.31 The Maytag brand is now part of Whirlpool Corporation, which has embraced this experience perspective in its companywide innovation efforts. Its Duet washer-and-dryer system focuses on making the set good-looking in the laundry room (like parking a luxury sports car in a garage). For garages, Whirlpool invented Gladiator GarageWorks, a set of appliances for garage-organizing. And its new Personal Valet offers a “clothes vitalizing system”—a device that is neither dry cleaning nor drying clothes on an outside line, but somehow feels like both. Innovators conceived of all these new inged things by rethinking the experiences consumers had while using appliances (and rooms) in the home.

Many goods encompass more than one experiential aspect, opening up multiple areas for differentiation. Apparel manufacturers, for instance, could focus on the wearing experience, the cleaning experience, and perhaps even the hanging or drawering experience. (And, like Guttman, they should not be afraid to make up new gerunds whenever needed.) Office supply businesses might create a better briefcasing experience, wastebasketing experience, or computer-screening experience. If you as a manufacturer start thinking in these terms—inging your things—you’ll soon be surrounding your goods with services that add value to the activity of using them and then surrounding those services with experiences that make using them more memorable—and therefore make more money.

Any good can be inged. Consider duct tape. ShurTech Brands of Avon, Ohio, employs a number of exemplary methods to turn duct-taping into a more memorably engaging experience via its Duck Tape brand. It does this first by embedding the goods in an experiential brand.32 The brand sports a duck mascot named Trust E. Duck. More than a logo, the duck serves as an all-encompassing motif for organizing almost every customer interaction with the inged brand. This embedding even extends to (or arguably begins with) the brand’s interactions with employees: ShurTech’s corporate offices, dubbed “The Duck Tape Capital of the World,” represent a themed office that does to office parks what Disney did to amusement parks. The company also emphasizes that it is producing goods experience stagers need. The website for Duck Tape provides a place for the company and its customers to share ideas for various “Ducktivities” that show how the goods can be used in staging various experiences. For example, you can find instructions on how to make a stylish Halloween bag entirely out of Duck Tape.

These kinds of experience-supporting insights are enabled by first sensorializing the goods. This represents perhaps the most straightforward way of making goods more experiential—by adding elements that enhance the customer’s sensory interaction with them. Some goods richly engage the senses by their very nature: toys, cotton candy, home videos, music CDs, cigars, wine, and so forth. While the very use of these goods creates a sensory experience, companies can sensorialize any good by accentuating the sensations created from its use.33 Doing so requires being aware of which senses most affect customers (but are perhaps most ignored in the traditional design of goods), focusing on those senses and the sensations they yield, and then redesigning the good to make it more experientially appealing. One way ShurTech does this is by colorizing the goods, offering Duck Tape in twenty colors and challenging customers to “Show Your True Colors.”

The company then allows customers to show off their Duck Tape creations by forming a goods club. Members of the “Duck Tape Club” share tips and tell stories about their adventures using the goods (Duck Tape hammock-swinging, anyone?) as well as gain access to exclusive promotional offers. The company itself gets into the inging action by making some goods scarce. For example, ShurTech made the “world’s largest roll of Duck Tape” and sent the one-of-a-kind product on a tour of select retail outlets for fans to get a special look (and feel) of the thing.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the company keeps busy staging goods events. Each year, the brand sponsors its “Stuck on Prom” contest, in which high school seniors win college scholarships by donning their tuxedos and gowns—made entirely out of Duck Tape—at their proms and then submitting photographs to ShurTech for judging. Similarly, a “Duck Tape Dad of the Year” contest finds many duct-taping fathers vying for accolades. And ShurTech helps host the “Avon Heritage Duct Tape Festival,” held each June in the company’s hometown. The goods event features, among other inged things, a parade of Duck Tape creations.

Many manufacturers stage their own goods events—although these experiences generally exist as a sideline—when they add museums, amusement parks, or other attractions to their factory output. Hershey’s Chocolate World—where else but in Hershey, Pennsylvania?—is perhaps the most famous, but there are others, including Spamtown USA (Hormel Foods, Austin, Minnesota), Goodyear World of Rubber (Akron, Ohio), The Crayola Factory (Binney & Smith, Easton, Pennsylvania), LEGOLAND Billund (Denmark), The Guinness Storehouse (Dublin, Ireland), and the Heineken Experience (Amsterdam, The Netherlands).34 Not every manufacturer can turn extra space into a ticket-taking museum, but any company can recast production as a miniaturized plant tour, thus turning the everyday acquisition and consumption of a candy bar, toy, drink, or any other good into a memorable event. The goal is to draw the customer into the process of designing, producing, packaging, and delivering the item. Customers often value the way in which they obtain something as much as the good itself: witness the great feeling Volkswagen engenders when customers pick up their new cars at the company’s Autostadt theme park, next to its plant in Wolfsburg, Germany.

The purpose of inging anything is to shift the attention from the underlying goods (and supporting services) to an experience wrapped around these traditional offerings, forestalling commoditization and increasing sales of the goods. Consider the Gumball Wizard machines found outside untold numbers of retail stores around the world. Put in a coin and the gumball spirals around and around before being dispensed, clickety-clacking as it goes. The device offers the same old goods—while, arguably, providing worse service because it takes longer to deliver the gumball. But the gumball-spiraling experience, atop the goods and service, drives increased sales.

The First Principle of Experience Staging

Staging compelling experiences begins with embracing an experience-directed mindset, thinking not only about the design and production of things but also about the design and orchestration of experiences using these things. Achieving this mindset begins with thinking in terms of ing words. Consider this ing thinking the first principle of effective experience staging.

This principle furnishes a powerful first step in helping businesses and industries shift from goods and services to experiences. For example, thinking in ing words led to the formation of the Go RVing Alliance—composed of the Recreational Vehicle Industry Association, the Recreational Vehicle Dealers Association, and other industry groups—to collectively promote the pleasures of RVing in lieu of individual manufacturers being left to pitch the features and benefits of competing RVs.

Wholeheartedly embracing the “ing the thing” principle can even lead to the launch of new experience-based businesses. Consider Build-A-Bear Workshop. Instead of just creating new teddy bear goods, founder Maxine Clark envisioned a special place where “kids aged 3 to 103” could create their own stuffed animals. The experience consists of eight stuffed animal-making stations: Choose Me (with kids choosing from some thirty animal skins), Hear Me (for recording a message or selecting a prerecorded sound for an inserted sound chip), Stuff Me (helping stuff the animal and then hugging it to test for the right amount of stuffiness), Stitch Me (including making-a-wish and then heart-inserting), Fluff Me (where kids enjoy hair-brushing and pampering their new creations in a spa treatment), Name Me (naming the animal and receiving a birth certificate), Dress Me (dressing the animal to show personality), and finally Take Me Home (instead of putting the animal in a shopping bag, housing the custom-made animal in a “Cub Condo Carrying Case,” a home-shaped box doubling as a coloring book—make that a coloring house). Online, the company posts ideas about housecationing while enabling virtual playing in Build-A-Bearville.

Ing One and Ing Two

You can uncover two types of experiences in the process of thinking about how to ing. The first category consists of those ing words that exist in your company’s everyday lexicon but are neglected as an experience in its offerings. Addressing these dormant opportunities can yield immediate experience enhancements. Consultant John DiJulius, for example, works with retailers to turn mundane store greetings into engaging encounters. You know the typical drill: the store associate says, “Can I help you?” only to have customers respond with “I’m just looking.” To ing the greeting at JoAnn Fabrics, DiJulius suggested asking, “What are you working on?” Most customers enjoy talking about their craft projects enthusiastically, so the new welcoming experience creates greater opportunity for sales floor staff to make suggestions about possible supplies. Almost every retailer stands to gain from rethinking its greeting. Similarly, almost every airline could stand to ing the intrusive reviewing of in-flight safety instructions by flight attendants over the plane’s loudspeakers. Southwest Airlines, of course, ings the thing by allowing staff to sprinkle these announcements with humor and even song. Virgin America rivals this with animated cartoon characters reviewing procedures on the entertainment system screen mounted on each seat.

Some neglected ing words provide fodder for significant innovation. Recognizing milk-drinking as an opportunity, cereal restaurateur Cereality invented a new utensil called the sloop. “The spoon that sips like a straw” has a hollow core running from the curved spoon end to the tip of the handle. Chick-fil-A saw store openings as a neglected experience. Whenever the Atlanta-based company opens a new location, it offers free chicken for a year to the first one hundred customers. These people always show up twenty-four hours in advance to camp out overnight on the store grounds. Chick-fil-A hosts ongoing games and other events in the parking lot throughout the gathering. CEO Dan Cathy typically joins the festivities in the evening to give a motivational speech and play his trumpet at key moments (“Revelry” as the morning wake-up call, and horse racing’s “Call to Post” when the store officially opens). Many customers post pictures and videos online as well as blog about their experiences.

In Simsbury, Connecticut, kitchen and bathroom remodeler Mark Brady of Mark Brady Kitchens seized on the selecting of appliances, cabinetry, fixtures, paint, wallpaper, and other renovation accessories as an opportunity to create a “shopping cruise” for prospective customers. Brady books a stretch limousine and chaperones customers (usually couples) on a tour of more than a dozen supply houses, guiding them through a workbook he prepared for fostering discussion between stops. The shopping cruise not only saves time (customers no longer have to navigate their way to all these outlets in the industrial parts of towns), but it also doubles as a great date (the limo driver opens doors and offers snacks, and Brady himself proposes a Champagne toast at the end of the tour). Customers not only make all the necessary selections for their room but also get to know Mark Brady and get comfortable with him as their contractor. (Brady also offers to apply the $750 cost of the shopping cruise to the price of his proposed work.)

So ask yourself, What ing word is being most neglected within our enterprise? Once you identify the opportunity, make it your focus for creating an engaging experience for your customers.

But go one step further. A second category of ing words consists of newly created words—like puffin birding, cross-golfing, noboarding, and housecationing—coined to describe new-to-the-world experiences. (Of course, any new and therefore unfamiliar ing word and its corresponding experience, once popularized, become familiar and therefore “existing” in the sense used here; think of bungee-jumping, which was once a foreign concept but now is enjoyed in almost every resort city in the world.) This approach focuses on inventing new experiences suggested by made-up ing words. The emergence of new ing words arises naturally whenever a truly new good serves as a prop or a new service sets the stage for a new experience. Think about how Apple’s iPod (a good) and iTunes (a service) gave rise to podcasting—now familiar to most of us—and podjacking—not yet so familiar: it refers to two people exchanging iPods to check out each other’s playlists. (Of note: the spell-checker associated with the software used to write this chapter recognized the former pod-based ing word but not the latter.)

Although the objective—experience innovation—remains the same with either mental model, people often find it easier to imagine new experiences emerging from new words. U.K.-based TopGolf, for example, operates facilities on multiple continents that go beyond mere improvement on the driving range (generally designed only for practicing for subsequent eighteen-hole golf course experiences). Instead, TopGolf offers a self-contained golfing experience in and of itself. With microchips embedded in each golf ball and landing areas that detect which person hit what ball where, it scores buckets, with results for each round posted on computer monitors—a kind of everyman’s leaderboard tracking for those topgolfing at any particular time. Or consider zorbing. New Zealand-based Zorb places people inside three-meter-diameter transparent plastic balls—they’re actually spheres within spheres—dubbed zorbs, and then rolls them down a hill!

Chicago provides the scene for two other examples of creating new experiences that no existing ing words suffice to describe. Call the one “cow-parading” and the other “bobble-buzzing.” The Greater North Michigan Growth Association hosted “Cows on Parade” in the mid-1990s, commissioning local artists to decorate three hundred bronze cows imported from Switzerland and, once they were completed, placed the finished art pieces throughout the city to promote tourism. The event proved so popular that untold cities followed suit, using other objects ranging from guitars (Cleveland) to flying pigs (Cincinnati) to Peanuts characters (St. Paul, Minnesota) to huge resin ducks (Eugene, Oregon, home of University of Oregon Ducks sports teams).

The other Chicago experience was a B2B marketing experience. Well, actually, it might be better described as an A2A experience, conducted by the Association Forum of Chicagoland, a professional society for directors and managers of other associations based in the greater Chicago area. After years of struggling to recruit members from the ranks of readily identifiable nonmember associations, the group conceived a new inged approach. Rather than conduct yet another direct-mail campaign to thousands of prospects yielding only a handful of new members, the society sent bobblehead dolls of the association’s executive director and volunteer president (customized at whoopassenterprises.com) to only the thirty most active members. Each bobblehead was packed in a “Care and Nurturing” kit that included postcards of the figures photographed at various Chicago landmarks (for mailing to friends in other associations), instructions for displaying the bobblehead for visitors to see in the members’ offices, and, most pertinently, applications for membership. As a result of the bobble-buzzing experience, more than three hundred new members joined the Association Forum of Chicagoland, representing a tenfold return on mailings versus the less than 1 percent success rate associated with previous efforts.

So ask yourself, What new ing word could be the basis of creating a wholly new experience? Once you have articulated the word, explore the elements that would help turn the new term into a wildly successful experiential reality.

The Progression of Economic Value

As the placard Rebecca Pine once gave to her father for his birthday says, “The best things in life are not things.” Consider a common event everyone experiences growing up: the birthday party. Most baby boomers can remember childhood birthday parties when Mom baked a cake from scratch. Which meant what, exactly? That she actually touched such commodities as butter, sugar, eggs, flour, milk, and cocoa. And how much did these ingredients cost back then? A dime or two, maybe three.

Such commodities became less relevant to the needs of consumers when companies such as General Mills, with its Betty Crocker brand, and Procter & Gamble, with Duncan Hines, packaged most of the necessary ingredients into cake mixes and canned frostings. And how much did these goods cost as they increasingly flew off the supermarket shelf in the 1960s and 1970s? Not much, perhaps a dollar or two at most, but still quite a bit more than the cost of the basic commodities. The higher cost was recompense for the increased value of the goods in terms of flavor and texture consistency, ease of mixing, and overall time savings.

In the 1980s, many parents stopped baking cakes at all. Instead, Mom or Dad called the supermarket or local bakery and ordered a cake, specifying the exact type of cake and frosting, when it would be picked up, and the desired words and designs on top. At $10 to $20, this cake-making service cost ten times the price of the goods needed to make the cake at home while still involving less than a dollar’s worth of ingredients. Many parents thought this a great bargain, however, enabling them to focus their time and energy on planning and throwing the actual party.

What do families do now in the twenty-first century? They outsource the entire party to companies such as Chuck E. Cheese’s, Jeepers!, Dave & Buster’s, or myriad other local “family entertainment centers,” or this Zone or that Plex of one kind or another. These companies stage a birthday experience for family and friends for $100 to $250 or more, as depicted in figure 1-4. For Elizabeth Pine’s seventh birthday, the Pine family went to an old-time farm called the New Pond Farm in Redding, Connecticut, where Elizabeth and fourteen of her closest friends experienced a taste of the old Agrarian Economy by brushing cows, petting sheep, feeding chickens, making their own apple cider, and taking a hay ride over the hill and through the woods.35 When the last present had been opened and the last guest had departed, Elizabeth’s mom, Julie, got out her checkbook. When Dad asked how much the party cost, Julie replied, “A hundred and forty-six dollars—not including the cake”!

FIGURE 1-4

Price of birthday offerings

The simple saga of the birthday party illustrates the Progression of Economic Value depicted in figure 1-5.36 Each successive offering—pure ingredients (commodities), packaged mixes (goods), finished cakes (services), and thrown parties (experiences)—greatly increases in value because the buyer finds each more relevant to what he truly wants (in this case, hosting a fun-filled and effortless birthday party). And because companies stage many kinds of experiences, they more easily differentiate their offerings and thereby charge a premium price based on the distinctive value provided, and not the market price of the competition. Those moms who baked from scratch paid only a few dimes’ worth of ingredients. Similarly, the old-time farm accrues relatively little marginal cost to stage the birthday experience (a few dollars for labor, a little feed, and an hour or two’s worth of depreciation) to turn a nice profit.37

FIGURE 1-5

Progression of Economic Value

One company that illustrates how to generate increased revenue and profits by shifting up the Progression of Economic Value is The Pleasant Company, now a part of Mattel. Founded in the 1980s by Pleasant Rowland, a former schoolteacher, the business manufactures a collection of American Girl dolls. Each one is cast in a period of American history and has its own set of a half-dozen fictional books placed in that time period. Girls learn U.S. history from owning the dolls and reading the books, which are marketed to their parents via catalog and the Web. In November 1998, the company opened its first American Girl Place off Michigan Avenue in Chicago, an ingeniously themed venue supported by sensation-filled sets (a doll hair salon, a photo studio, a restaurant simply called “Cafe,” showcase displays for each doll, and various nooks for cuddling up with a book or doll), engaging staff performances (arriving at the concierge desk, visiting the hospital reception used for dolls in need of mending, and at nearly every turn), and a host of special events (theme parties, “Late Night” after-hours tours, and of course birthday parties). It’s hard to call the American Girl Place a retail store, because it is indeed a business stage for experiences. Certainly you can purchase dolls, books, furniture, clothing, and various kits galore—even children’s clothing that matches the dolls’ outfits. But the merchandise proves secondary to the overall experience, at which guests average (average!) more than four hours per visit.

And do the math. A family may visit an American Girl Place and shell out $20 for a photography shoot—complete with preparatory makeup session—with the photo printed on a customized cover of American Girl magazine (subscriptions sold separately for $19.95 for six non-customized issues per year), pay another $20 in the hair salon for the doll to be restored to its original coiffed condition, and then dine at the Cafe at prix fixe prices, including gratuity, ranging from $17 to $26 for brunch, lunch, tea, and dinner. Even if they forgo a birthday celebration (at $32 per person, or $50–$65 for deluxe versions) or a late night event (for $200–$240 per girl), a family can easily spend hundreds of dollars—without buying a single physical thing! Of course, spending that much time and money on experiences then creates greater demand for traditional American Girl goods to commemorate the visit.

The company has expanded its portfolio of experiences to include American Girl Places in New York City (off Madison Avenue) and Los Angeles (at The Grove), as well as new (smaller footprint) American Girl Boutique & Bistros in Atlanta, Boston, Dallas, Denver, and the Mall of America. Sales soar, not only from the revenue generated at these retail venues but also from home via catalog shopping and at the company’s website. These sales from home have undoubtedly accelerated as a result of the company’s creating these away-from-home experiences to fuel the demand, for in today’s Experience Economy, the experience is the marketing.

Let the Action Begin

Other children’s experiences, such as The Little Gym and KidZania, now circle the world. Kids’ camps are big business, as are various “travel teams” in their associated sports leagues, often supported with additional payments for ongoing sports lessons and personal coaching. Adults frequent cooking schools, fantasy camps, and wellness spas, among other indulgent experiences. Unique experiences constantly emerge: a place called Dig This in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, offers the B2C equivalent of the Case Tomahawk digging experience; one of its offerings, Excavate & Exfoliate, combines construction equipment play with follow-up spa treatments. Thus whole new genres of tourism arise; witness film tourism, culinary tourism, medical tourism, disaster tourism, climate change tourism, even “PhD tourism” (Context Travel of Philadelphia assigns doctorate experts to travel with tourists to various European cities). Airports, foremost among them the Amsterdam Airport Schiphol, have become experiential shopping centers. They serve as way stations to bizarre new attractions and destinations, such as Ski Dubai, Icehotel and its spinoff Icebars, and Atlantis in the Bahamas and Dubai—only to be topped by the Burning Man festival in the Black Rock Desert in Nevada. Back home, malls have become “lifestyle centers.” Cafe culture abounds, from Starbucks and Caribou to the International Netherlands Group’s ING Direct Cafes. Fitness centers seek to differentiate via the experience offered, from themed Crunch, to no-frills Curves, to large-scale Lifetime Fitness. Ian Schrager Company introduced the world to “boutique” hotels, followed soon by Kimpton Hotels, Joie de Vivre Hospitality, Starwood’s W, and hundreds of independents represented by Design Hotels (based in Berlin). Blue Man Group and Cirque du Soleil offer truly new-to-the-world staged experiences. Museum experiences are being fundamentally rethought; visits to the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C., the Harley-Davidson Museum in Milwaukee, and the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois, clearly offer a new kind of encounter. The Internet offers new online experiences, from the U.S. Army’s America’s Army game at americasarmy.com to Linden Research’s Second Life and Blizzard Entertainment’s World of Warcraft. New experiences are available even at the end of life; Givnish Funeral Homes, outside Philadelphia, offers Life Celebration capabilities to other funeral directors throughout the United States. It is hard to find an industry still untouched by the shift to experiences.

Of course, no one has repealed the laws of supply and demand. Companies that fail to provide consistently engaging experiences, overprice their experiences relative to the value received, or overbuild their capacity to stage them will see demand or pricing pressure. For example, Discovery Zone, one stalwart of the birthday party circuit, went belly-up because of inconsistently staged events, poorly maintained games, and little consideration of the experience received by the adults, who, after all, pay for the event.38 Planet Hollywood saw same-store sales plummet and had to significantly scale back its number of locations because it failed to refresh its experiences. As with most theme restaurants, repeat guests see (or do) little different from what they saw and did on previous visits. Even Disney succumbed to this problem when it let Tomorrowland grow horribly out of date over the past couple of decades; and the company had to invest billions to relaunch Disney’s California Adventure Park after a lukewarm reception of the initial offering by Disney enthusiasts.

As the Experience Economy continues to unfold in the twenty-first century, more than a few experience stagers will find the going too tough to stay in business. Only the best of theme-based restaurants launched in the 1990s, for example, survived into the new millennium. But such dislocations occur as the result of any economic shift. Once, there were more than a hundred automakers in eastern Michigan, and more than forty cereal manufacturers in western Michigan. Now there are only the Big Three in Detroit (depending on how you want to count it these days) and the Kellogg Company in Battle Creek, all stalwarts of the Industrial Economy.

The growth of both the Industrial Economy and the Service Economy brought with it a proliferation of offerings that did not exist before imaginative companies invented and developed them. That’s also how the Experience Economy will grow, as companies tough out what economist Joseph Schumpeter termed the “gales of creative destruction” that constitute business innovation. Those businesses that relegate themselves to the diminishing world of goods and services will be rendered irrelevant. To avoid this fate, you must learn to stage a rich, compelling experience.