2

Setting the Stage

On a hot August night you find yourself in Evanston, Illinois, at the corner of Dempster and Elmwood. You spy a storefront named LAN Arena and, wondering what it might be, step inside. A T-shirted Gen Xer with “Commander Francisco” printed on his badge looks your way and mouths some words of greeting from atop his elevated platform. You nod in that general direction but decline his offer to explain the strange surroundings as you take a few more paces inside.

The walls are bare, the floor nearly empty. A faint odor of cement after a summer rain wafts its way into your nostrils. The tonal range looks decidedly gray. The sights and sounds soon draw your focus to the very heart of the place, in front of the Commander’s platform, where finally you behold the domain he rules: fourteen PCs with large monitors, standard keyboards, and assorted gadgetry, half of them tethered to obviously quick-moving and presumably quick-witted people. You now identify the background noise that has been omnipresent from the moment you opened the door: the clicking and clacking of fingers on keys combined with the smooth sliding of joysticks. A yelp goes up from one of the six souls whose eyes focus on the screens before them: “Go away, you greasy-haired piece of monkey brains!” he yells, as you reflexively jump behind a pillar. Feeling foolish, you realize the taunt was aimed not at you but at an unseen combatant sparring with the truly greasy-haired piece of animated humanity before you. Another person mutters, “Who’s in there? Careful! You’re not getting off that easy!” A third shouts mild obscenities, punctuated by the occasional repeatable word.

As you walk around, desiring a closer look at both the human beings and their cybernetic appendages, you see that every PC has a nameplate: Toby, Fergie, Grape Ape, and—somehow you knew this was coming—Larry, Moe, and Curly. The screamer bangs away at Eastwood, the mutterer at one named Buddha. You glance back at Commander Francisco and notice for the first time that behind him are a number of shelves filled with row upon row of software boxes. Here, more names greet you: Diablo, Red Alert, Warcraft II, Command & Conquer. Ah! That’s it! They’re all playing some computer-based game against each other. “It’s called Quake,” the Commander announces, having watched your exploration of the place and now sensing your need to know. “It’s sort of an electronic version of capture the flag.”

You finally understand the attraction of this place and soon gain vicarious enjoyment from watching the players play. Three on three, the virtual opponents, physically seated less than twenty feet apart, battle in a virtual arena by means of a local area network, or LAN. You see the excitement in each player’s face, the fluidity of human and machine working as one, and finally the joy that resounds in the one final cry of the victor as he vanquishes his last opponent. While disappointed in their loss, the also-rans all too happily begin anew. Hesitantly, anxiously, eagerly, you inform the Commander that you wish to join them. You sit down at a station and begin to experience the play for yourself.

This narrative, written in the second-person style endemic to certain kinds of computer games, more or less describes the real-life LAN Arena as we first experienced it. It was the kind of place like many others that dotted the urban landscape in the late 1990s, where for a fee people played computer-based games against like-minded competitors. Commander Francisco Ramirez—who, in addition to being our host, was also one of three co-owners—explained that one could join in for $5 to $6 per hour and that regulars could select annual membership plans ranging between $25 and $100 to receive discounted rates, reserve a spot in the LAN Arena Directory, and play in occasional tournaments.

Despite the evident popularity of the LAN Arena, we couldn’t help getting the feeling that the place resembled all the mom-and-pop video stores that mom-and-popped up across the country twenty-five or thirty years ago. The self-owned and -run local video store is now largely a historical curiosity—an interim solution—thanks to the creative destruction of alternative formats and innovative distribution and merchandising programs created by bigger enterprises. Not to mention industry consolidations, culminating in the wide swath cut by Blockbuster to gain the lion’s share of the nascent industry’s revenues. Then, of course, Blockbuster faced yet newer competition from outlet-free Netflix and its time-based pricing model, offering unlimited viewing experiences for a monthly fee in lieu of per-rental service charges (and pesky late fees).

Similarly, the LAN Arena format, with players seated together at a common site, proved only an interim solution before the play-at-home games of the past gave way to the play-in-cyberspace games of today. LAN Arena offered a ready-to-play gaming environment that was less costly and cumbersome than setting up the same arrangement at home, before the cost of faster hardware plummeted and broadband service became plentiful and free. Today, faster play is generally available on the Internet, and multiple players can readily participate simultaneously in the same Quake game or myriad others online. Indeed, the competitive landscape for gaming experiences knows few boundaries.1

Interestingly, as direct, online, from-home competitions came to dominate the gaming experience, “LAN parties” proliferated as pop-up events in cities around the world. Evidently the now-defunct LAN Arena was on to something. The social interaction, the game outside the game, weighs just as importantly in the enjoyment of software-enabled games as it does with the old table-top board games. Technology pundits anticipate that real-time audio, video, and tactile technologies will advance to the point that in a few years we’ll be able to experience all interactions—yells and glares, teases and taunts, perhaps even pushes and shoves—virtually as well as we now do in reality. Evidently, no cyber game experience will be complete without its attendant virtual social experience.2

In the meantime, the staging of these LAN party experiences in physical venues has itself become a large-scale production. At about the same time LAN Arena opened in Evanston, id Software, the developers of Quake, launched QuakeCon. Now in its fifteenth year, the event features a QUAKE LIVE Masters Championship for advanced players (with a $50,000 purse for the winner), a four-on-four “Capture the Flag” competition, and an open tournament for less-skilled players—all held in an intimate 250-person arena, with others watching via streaming video. The competition comes complete with “shoutmasters” covering the action, culminating in a giant 3,000-person LAN party.

The future mix of virtual and physical action remains to be seen, and there is always the possibility that new social interfaces might even mask the interplay between the two. In any case, it is clear that not every company that stages these new experiences will be successful in the short term, much less the long term. Only a few will survive. What we don’t know are which ones. Those that thrive will do so because they treat their economic offering as a rich experience—and not a glorified good or celebrated service—and will stage it in a way that engages the individual and leaves behind a memory. That means not making the mistake we see time and time again: equating experiences with mere entertainment.

Enriching the Experience

Because many exemplars of staged experiences come from what the popular press loosely calls the entertainment industry, it’s easy to conclude that shifting up the Progression of Economic Value to stage experiences simply means adding entertainment to existing offerings. That would be a gross understatement. Remember that staging experiences is not about entertaining customers; it’s about engaging them.

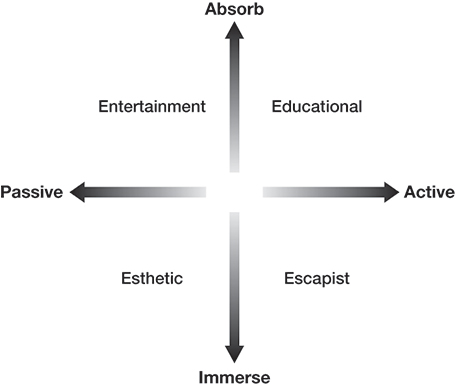

An experience may engage guests on any number of dimensions. Consider two of the most important, as depicted in the axes of figure 2-1. The first dimension (on the horizontal axis) corresponds to the level of guest participation. At one end of the spectrum lies passive participation, in which customers do not directly affect or influence the performance. Such participants include symphony goers, who experience the event purely as observers or listeners. At the other end of the spectrum lies active participation, in which customers personally affect the performance or event that yields the experience. Active participants include skiers, who participate in creating their own experience. But even people who turn out to watch a ski race are not completely passive; simply by being there, they contribute to the visual and aural event that others experience.

FIGURE 2-1

Experience realms

The second (vertical) dimension of experience describes the kind of connection, or environmental relationship, that unites customers with the event or performance. At one end of this spectrum lies absorption—occupying a person’s attention by bringing the experience into the mind from a distance—and at the other end is immersion—becoming physically (or virtually) a part of the experience itself. In other words, if the experience “goes into” guests, as when watching TV, then they are absorbing the experience. If, on the other hand, guests “go into” the experience, as when playing a virtual game, then they are immersed in the experience.

People viewing the Kentucky Derby from the grandstand absorb the event taking place before them from a distance. Meanwhile, people in the infield are immersed in the sights, sounds, and smells of the race itself as well as the activities of the other revelers around them. Students inside a lab during a physics experiment are immersed more than when they only listen to a lecture; seeing a film at the theatre with an audience, a large screen, and stereophonic sound immerses people in the experience far more than if they were watching the same film at home on the family room TV.

The coupling of these dimensions defines the four realms of an experience—entertainment, educational, escapist, and esthetic, as shown in figure 2-1—mutually compatible domains that often commingle to form uniquely personal encounters. The kind of experiences most people think of as entertainment occur when they passively absorb the experiences through their senses, as generally occurs when they view a performance, listen to music, or read for pleasure. But even though many experiences entertain, not all of them are, strictly speaking, entertainment, defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “the action of occupying a person’s attention agreeably; amusement.”3 Entertainment provides not only one of the oldest forms of experience (surely jokes have been around at least since the beginning of humankind) but also one of the most developed and, today, the most commonplace and familiar. (The “unproductive labourers” Adam Smith singled out were all entertainers: “players, buffoons, musicians, opera-singers, opera-dancers, &c.”) As the Experience Economy gears up, people look in new and different directions for increasingly unusual experiences. At the same time, few of these experiences exclude at least momentary entertainment, making people smile, laugh, or otherwise enjoy themselves. But there are also opportunities for those enterprises staging these experiences to add to the mix components of the other three realms of experience: the educational, the escapist, and the esthetic.

The Educational

As with entertainment experiences, in educational experiences the guest (or student, if you prefer) absorbs the events unfolding before him. Unlike entertainment, however, education involves the active participation of the individual. To truly inform people and increase their knowledge or skills, educational events must actively engage the mind (for intellectual education) or the body (for physical training). As Stan Davis and Jim Botkin write in The Monster Under the Bed, “The industrial approach to education . . . [made] teachers the actors and students the passive recipients. In contrast, the emerging new model [of business-led education] takes the market perspective by making students the active players. The active focus will shift from the provider to the user, from educat-ors (teachers) to learn-ors (students), and the educating act will reside increasingly in the active learner, rather than the teacher-manager. In the new learning marketplace, customers, employees, and students are all active learners or, even more accurately, interactive learners.”4

Judith Rodin, former president of the University of Pennsylvania, also recognized the active nature of education, as well as the fact that learning is not limited to the classroom. In her 1994 inaugural address she proclaimed, “We will design a new Penn undergraduate experience. It will involve not only curriculum, but new types of housing, student services, and mentoring, to create a seamless experience between the classroom and the residence, from the playing field to the laboratory. I am committed to having this in place for students entering Penn in the fall of 1997. That class—the Class of 2001—will be our first class to have an entirely new experience—the Penn Education of the Twenty-First Century.”5 Before leaving Penn in 2005 to head the Rockefeller Foundation, Rodin followed up her plan with a report outlining the progress made in successfully enhancing the educational value derived from all of campus life.

Although education is serious business, this doesn’t mean that educational experiences can’t be fun. The term edutainment was coined to connote an experience straddling the realms of education and entertainment.6 Blending learning with fun occurs at each of the writing and tutoring centers affiliated with the nonprofit educational organization 826 National. Beginning with the first 826 location that opened in 2002 in San Francisco as 826 Valencia, each center features a uniquely themed storefront that acts as a portal of fun through which children (ages six through eighteen) must pass on their way to one-on-one tutoring, writing workshops, or other educational events. Each portal operates as a fully functioning retail store, exclusively selling merchandise in keeping with the location-specific motif (with proceeds helping fund the core learning sessions). At the original 826 Valencia, it’s simply the Pirate Supply Store. Subsequent stores offer much richer edutainment: Brooklyn Superhero Supply Co. (“purveyors of high quality crimefighting merchandise”) at 826 NYC; Echo Park Time Travel Mart at 826 LA; Liberty Street Robot Supply & Repair at 826 Michigan in Ann Arbor; The Boring Store at 826 Chicago, Greenwood Space Travel Supply Company at 826 Seattle; the Bigfoot Research Institute at 826 Boston; and the Museum of Unnatural History at 826 DC in Washington, D.C. By emphasizing creative and expository writing as the active measure of successful tutoring (many locations publish student material in bound book form) and by absorbing fun with each visit, students find that tutoring, formerly a dreaded experience, becomes much-desired learning.

The Escapist

Memorable encounters of a third kind—escapist experiences—involve much greater immersion than do entertainment or educational experiences. In fact, escapist experiences are the polar opposite of pure entertainment. Guests of escapist experiences are completely immersed in them as actively involved participants.7 Examples of essentially escapist environments include generally artificial activities—trekking about in theme parks, gambling at casinos, playing computer-based games, chatting online, or even participating in a game of paintball in the local woods—as well as more natural ones, like the “thrilling escapes” featured in Peter Guttman’s book Adventures to Imagine. Rather than play the passive role of couch potato, watching others act, people become actors, able to affect the actual performances.

One might enhance the inherent entertainment value of a movie, for example, not only with larger screens, bigger sound, cushier chairs, VIP rooms, and so forth, but also by having customers actually participate in the thrill of movement. Myriad companies now bring such experiences to a neighborhood near you via motion-based attractions.8 Early stars of this genre include Tour of the Universe, a group flight through outer space from SimEx of Toronto; Magic Edge, a simulation of a military dogfight for multiple players in Mountain View, California, and Tokyo; and Disney’s Star Tours, a simulation of a heroic battle for galactic domination based loosely on the Star Wars movies.

Most such escapist experiences are essentially motion simulator rides based on popular adventure or science fiction movies. Additional examples include Back to the Future: The Ride and Terminator 2: Battle Across Time hosted at Universal Studios in Orlando and Aladdin’s Magic Carpet at Walt Disney World. These rides perfectly express the shift from the Service to the Experience Economy. It used to be, “You’ve read the book, now go see the movie!” Today, it’s, “Now that you’ve seen the movie, go experience the ride!”9

Despite the appellation, guests participating in escapist experiences not only embark from but also voyage to a specific place and activity worthy of their time. For example, some vacationers, no longer content to only bask in the sun, go rollerblading, snowboarding, skysurfing, white-water kayaking, mountain climbing, or sports-car racing, or they take part in other extreme sports.10 Others try their hand at the time-honored art of gambling not only to forget all their troubles and forget all their woes but also because they enjoy the visceral experience of risking their money in opulent surroundings for a chance at greater fortune. Others want to escape their fortunes to see what it’s like conversing with the common man. Former Dallas Cowboys quarterback and TV commentator Troy Aikman, for instance, once told Sports Illustrated why he frequently visited America Online: “I like to go to the Texas Room and chat with people. It puts us on the same level. It’s nice, too, having a normal conversation with somebody without them knowing who I am.”11 While celebrities may value an experience that turns them into ordinary folks, many escapist experiences, such as computer-based sports games, let the average person feel what it’s like to be a superstar.

The Internet has indeed become a great place for such experiences, but many businesses still don’t get it. They’re heading into the commoditization trap, only selling their company’s goods and services over the World Wide Web, when in fact most individuals surf the Internet for the experience itself. Surprisingly, Pete Higgins, vice president of Microsoft’s Interactive Media Group, told BusinessWeek, “So far, the Internet isn’t a place for truly mindless entertainment.”12 But who wants it to be? The Internet is an inherently active medium—not passive, as television is—that provides a social experience for many people. Interactive entertainment is an oxymoron. The value people find online derives from actively connecting, conversing, and forming communities.

Formerly the domain of mom-and-pop outfits like The WELL, cyberspace was first brought to the masses by Prodigy, CompuServe, and America Online (mistakenly dubbed online “service” providers). AOL won the initial battle for members primarily because it understood that they wanted a social experience; they wanted to actively participate in the online environment growing up around them. While Prodigy at one point limited the amount of e-mail its members could send and CompuServe limited member identities to a string of impersonal numbers, AOL allowed its members to pick as many as five screen names (to suit the several moods or roles they might want to portray online).13 AOL also actively encouraged the use of features that connect people: e-mail, chat rooms, instant messages, personal profiles, and “buddy lists,” which let users know when their friends are also online. Even before AOL went to a flat-rate pricing scheme in late 1996, more than 25 percent of its 40 million connect-hours each month were spent in chat rooms, where members interacted with each other.14 AOL proved no match for the social media that soon followed—MySpace, Facebook, Twitter, Foursquare, and myriad specialty sites such as ChatRoulette—let alone the explosion of “apps” providing other escapist experiences via smartphones.

For some people, the Internet provides a welcome respite from real life, an escape from the humdrum routine and the harried rush. For many others, we suspect digital life has become the new distracted reality from which they increasingly seek to escape to an alternative, unplugged existence.15 It is still unclear how the near ubiquity of the Internet will ultimately alter the need most people have had for a physical place set apart from home and work, a “third place,” in the words of sociologist Ray Oldenburg, where people can interact with others they have come to know as members of the same community.16 These places—pubs, taverns, cafes, coffeehouses, and the like—once seemed to be on every street corner of every city, but the suburbanization of society has all too often left people too far apart to commune in this way. Some people now look for community in cyberspace, while others use vacations at themed attractions to connect with large masses of people.17 Still others find a middle ground at Starbucks or other such cafes.

The Esthetic

The fourth and last experiential realm we explore is the esthetic. In such experiences, individuals are immersed in an event or environment but have little or no effect on it, leaving the environment (but not themselves) essentially untouched. Esthetic experiences include standing on the rim of the Grand Canyon, beholding a work of art at a gallery or museum, and sitting at the Caffè Florian in Old World Venice. As mentioned earlier, being in the infield at the Kentucky Derby also qualifies. While guests partaking of an educational experience may want to learn, of an escapist experience want to go and do, of an entertainment experience want to enjoy, those partaking of an esthetic experience just want to be.18

At a Rainforest Cafe, for example, diners find themselves in the midst of dense vegetation, rising mist, cascading waterfalls, and even startling lightning and thunder. They encounter live tropical birds and fish as well as artificial butterflies, spiders, gorillas, and, if they look closely, a snapping baby crocodile.19 Note that the Rainforest Cafe, which combines a dining room with a retail shop and bills itself as “A Wild Place to Shop and Eat,” is not out to simulate the experience of being in a rain forest. Rather it aims to stage a certain esthetic experience that is the Rainforest Cafe.

Another wild place to shop can be found in Owatonna, Minnesota, at Cabela’s, a 150,000-square-foot outfitter of hunting, fishing, and other outdoor gear. Rather than add elements of entertainment to the store, Dick and Jim Cabela turned it into an esthetic experience, centered (literally) on a thirty-five-foot-high mountain with a waterfall and featuring more than a hundred stuffed taxidermic animals, many of them shot by the two brothers or other family members. This part of the store represents four North American ecosystems. Elsewhere, two huge dioramas depict African scenes that include the so-called Big Five big-game targets: the elephant, lion, leopard, rhinoceros, and cape buffalo. Three aquariums hold a number of varieties of prized fish, while almost seven hundred kinds of animals are mounted in every department of the store. Truly, as Dick Cabela told the St. Paul Pioneer Press, “We’re selling an experience.”20 So much so that more than thirty-five thousand people visited the refurbished store on the day it opened, and the company draws more than one million visitors every year.

The esthetic aspects of an experience may be completely natural, as when one tours a national park; primarily man-made, as when one dines at the Rainforest Cafe; or somewhere in between, as when one shops at Cabela’s. There’s no such thing as an artificial experience. Every experience created within the individual is real, whether the stimuli be natural or artificial. Extending this view, renowned architect Michael Benedikt discusses the role he believes architects play in connecting people to a “realness” within their created environments: “Such experiences, such privileged moments, can be profoundly moving; and precisely from such moments, I believe, we build our best and necessary sense of an independent yet meaningful reality. I should like to call them direct esthetic experiences of the real and to suggest the following: in our media-saturated times it falls to architecture to have the direct esthetic experience of the real at the center of its concerns.”21

While architects may lead, it falls to everyone involved in the staging of esthetic experiences to connect individuals and the (immersive) reality they directly (albeit passively) experience, even when the environment seems less than “real.” Benedikt would likely deem the Rainforest Cafe and similar venues “non-real” and insist that its architects address “the issue of authenticity by framing [displaying the inauthentic as inauthentic], by making fakery honest, as it were.”22 To stage compelling esthetic experiences, designers must acknowledge that any environment designed to create an experience is not real (the Rainforest Cafe, for instance, is not the rain forest). They should not try to fool their guests into believing it’s something it is not.

Architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable makes a similar distinction when she says, “It is becoming increasingly difficult to tell the real fake from the fake fake. All fakes are clearly not equal; there are good fakes and bad fakes. The standard is no longer real versus phony, but the relative merits of the imitation. What makes the good ones better is their improvement on reality.”23 To illustrate the difference, we’ll consider two invented environments Huxtable spends considerable time critiquing: Universal CityWalk and almost anyplace Disney.24

CityWalk in Los Angeles is a collection of retail shops, restaurants, movie theatres, high-tech rides, and low-tech kiosks, each with a distinctive façade. Controlled exaggeration abounds, as in the four-story guitar adorning the Hard Rock Cafe. Visitors lazily stroll through a water fountain that shoots up at well-timed intervals. Guests pay an entrance fee for parking (nobody walks to anything in L.A., so here they pay admission to walk around) that’s reimbursed only if they spend money at a dining or movie experience (purchases of goods merit no reimbursement). Part theme park and part public square, CityWalk primarily imparts an esthetic experience, Huxtable confirms, because it “is being used for its own sake.”25 The realness of its fakery evidences itself from the very moment you park your car in the ungarnished lot. The back of the buildings greet arriving guests, who thus see the unadorned undersides of the façades as they walk in. Outside you see the inside of the mask; inside you see its outside. Adjacent buildings, not associated with CityWalk, remain visible through alleys and other offshoots to the main drag. Its esthetic acknowledges its fakeness. Through framing, it’s truly a real fake.

The esthetic of most Disney experiences, on the other hand, seeks to hide all things fake: no one gets to see behind the curtain. Parking lots smoothly flow into shuttle buses, welcoming booths, and turnstiles. Façades seamlessly integrate into one another, lest a guest detect the trickery in the dimensional downsizing. Mickey Mouse never takes off his mask, lest we see the pimply faced kid inside. It’s the fake fake that Huxtable and other critics decry, Disney not being true to what they deem it really is.

Or is it real fake fake? Other critics laud Disney for creating wholly immersive environments, consistent and engaging within themselves. One writes, “From whatever angle, nothing looks fake. Fabricated, yes—fake, no. Disneyland isn’t the mimicry of a thing; it’s a thing . . . I’m convinced the genius of Disneyland isn’t its fancifulness, but its literalism.”26 On the subject of Disney theme parks, many people (including we coauthors) disagree. But one thing remains clear: an esthetic experience must be true to itself or risk coming off as fake to its guests.

Experiencing the Richness

Companies can enhance the realness of any experience by blurring the boundaries between realms. While many experiences engage primarily through one of the four realms outlined earlier, most of them cross boundaries. British Airways, for example, stages a primarily esthetic experience: personnel pamper guests in an environment where they don’t have to do anything for themselves. But Robert Ayling, successor to Sir Colin Marshall as CEO, had the company continually working on enhancing in-flight entertainment systems and integrating them with the overall flying esthetic. Ayling believed that more people would see movies in the air than in cinemas. “Long-haul airlines,” he said, “will increasingly be seen not only as transport systems but as entertainment systems.”27 Virgin America has gone one step further, creating an animated cartoon to review safety instructions with passengers and installing mood lighting to alter the cabin ambiance during different times of the day.

American Express often mixes esthetic and educational elements in the Unique Experiences (AmEx’s capitalization) it offers those enrolled in its Membership Rewards program.28 In one such offer, Images of the Rain Forest—Photo Safari in Costa Rica, the company invited card members to join “celebrated nature photographers Jay Ireland and Georgienne Bradley for an unforgettable five-day photography workshop in Costa Rica’s flourishing rain forest” and tempted them with the following description: “Surrounded by wildlife, you’ll learn techniques and professional secrets that will enable you to capture astounding images. From cuddly Three-toed Sloths to majestic Great Egrets and comical Red-eyed Tree Frogs, you’ll have countless opportunities to shoot professional quality images of exotic animals. You’ll also enjoy enchanting views of the canals from the balcony surrounding your hotel, and be served first-class meals in the comfortable jungle setting. No matter what your photographic experience, this adventure promises to be unforgettable.”

To make retailing more unforgettable, most store executives and shopping mall developers talk about making the shopping experience more entertaining, but leading-edge companies also incorporate elements from the other experiential realms. For example, to engage the locals and tourists at the six-block retail and entertainment district Bugis Junction in Singapore, design firm CommArts of Boulder, Colorado, mined the historical trading culture of Singapore to create what cochairman Henry Beer calls “an esthetically pleasing built environment designed to connect the project deeply to the resident culture of Singapore.” Seaside architecture, sails, chronometers, and kindred elements fulfill the dominant motif, while bright signage informs and educates guests on the history of the native seafaring merchants known as the Bugis people. Similarly, for the Ontario Mills retail project, CommArts laid out streets and neighborhoods that provide a distinctive esthetic experience drawn from the rich heritage of Southern California. Unlike a traditional mall, Ontario Mills is not anchored by large department stores selling goods but instead by businesses staging large experiences—a thirty-screen AMC movie house, a Dave & Buster’s arcade and restaurant, a Rainforest Cafe, and the Improv Comedy Club & Dinner Theatre. One of its wings houses Steven Spielberg’s Gameworks, and another features a Build-A-Bear Workshop. As Beer related to us, “Competition for the retail dollar demands that we create a rich retail theatre that turns products into experiences.”

The richest experiences encompass aspects of all four realms. These center on the “sweet spot” in the middle of the framework.29 Consider the world’s largest flower park, Keukenhof, located in the South Holland region of The Netherlands. The park’s success results not from any one element but from the collective multi-realm experience it allows each visitor to enjoy traversing through the seventy acres of tulip fields, landscaped gardens, and indoor flower show pavilions. Featuring more than sixteen thousand varieties of flowers (including one thousand varieties of tulips alone, with more than six million bulbs hand-planted each year) and eighty-seven varieties of trees (twenty-five hundred in all), the venue deserves its reputation as “the garden of Europe.” The Dutch so meticulously manicure the garden that it offers a great place to just hang out and behold the flowers. (Some claim Keukenhof is the most photographed place on earth.) This esthetic value is enhanced through the placement of more than one hundred art statues as well as a half-dozen “inspirational gardens” that create a special sense of intimacy through the use of enveloping hedges, wooden fences, and walls. The escapist value of walking the fifteen kilometers of footpaths gets an uptick through the careful placement of a handful of elements designed to encourage visitors to interact with one another, such as a maze featuring three-meter-high shrubs and an elevated tree house in the center from which one can look down, see the pattern, and shout out (correct or incorrect) instructions. Small educational signs display the names and other horticultural information for all the varieties of flowers so that guests can learn about the varieties (taking notes for ordering bulbs and seeds later in the flower shop); tours and other programs provide lessons on the Dutch bulb-growing industry and the history of the Keukenhof chateau. For entertainment, guests periodically encounter small musical acts and eventually find their way to a pavilion featuring a water show, in which a fountain gyrates to synchronized music. These and other elements combine to create a truly compelling experience, drawing from all four experiential realms.

To design a rich, compelling, and engaging experience, you don’t want to incorporate only one realm. Instead, like those who designed Keukenhof, you want to use the experiential framework depicted in figure 2-1 as a set of prompts that help you creatively explore the aspects of each realm that might enhance the particular experience you wish to stage. When designing your experience, you should consider the following questions:

• What can be done to enhance the esthetic value of the experience? What would make your guests want to come in, sit down, and just hang out? Think about what you can do to make the environment more inviting and comfortable. You want to create an atmosphere in which your guests feel free “to be.”

• Once your guests are there, what should they do? The escapist aspect of an experience draws in your guests further, immersing them in various activities. Focus on what you should encourage guests “to do” if they are to become active participants in the experience. Further, what would cause them “to go” from one sense of reality to another?

• The educational aspect of an experience, like the escapist, is essentially active. Learning, as it is now largely understood, requires the full participation of the learner. What do you want your guests “to learn” from the experience? What interaction or activities will help engage them in the exploration of certain knowledge and skills?

• Entertainment, like the esthetic, is a passive aspect of an experience. When your guests are entertained, they’re not really doing anything except responding to (enjoying, laughing at, etc.) the experience. What entertainment would help your guests “to enjoy” the experience better? How can you make the time more fun and more enjoyable?

Addressing these design issues sets the stage for service providers to begin competing on the basis of an experience. Those that have already forayed into the world of experiences will gain from enriching their offerings in light of these four realms—as the means both to enhance current experiences and to envision whole new ones.

Consider ski resorts. The locale of the mountain drives the quintessentially escapist nature of the skiing itself. Almost all resorts offer lessons to provide educational value. In addition to lodges for après-ski experiences, many resorts have incorporated “ski-to” places as mid-mountain havens where guests can take a break from skiing, kick back—say, on comfortable Adirondack chairs—throw off the goggles, and catch some rays. But few resorts recognize the one place where the entertainment element is inherently part of the skiing experience and seek to enhance its value: the ski lift! It’s the place where people relive their runs, tell jokes and stories, and look below at fellow skiers. The commodity mindset mistakenly thinks the ski lift merely performs the function of transporting people from the bottom to the top of the mountain. An experience mindset—leveraging the four realms—would look for ways to add fun to the lift experience, perhaps mimicking hotelier Ian Schrager, who often turned his hotel elevators into unique experiences.

Schrager deserves credit for kick-starting the renewed interest in design in the hotel and lodging industry. Before Schrager, hotel lobbies offered little esthetic value and served largely as places for guests to meet other parties before leaving the premises. Schrager turned his lobby spaces into hip lounges that kept guests from wanting to wander away. And thanks to Starwood’s Westin Hotels and its “Heavenly Bed,” almost every hotel chain has reinvented its beds to address the age-old problem of getting to sleep in a strange place, enhancing the escapist value of a stay. The in-room experience has also seen vast improvements in offering greater entertainment value with the introduction of flat-screen televisions. What opportunity awaits to improve the educational experience? Perhaps reinventing concierge services, given that guests now have access to a great deal of information via in-room Internet access or their own handheld devices.

Similarly, medical providers should rethink the educational element of treatment, lest the ever-increasing availability of information online further frustrate doctors and patients as they communicate past each other. And what hospital or doctor’s office wouldn’t benefit from fundamentally rethinking the “waiting room” paradigm in order to increase the esthetic value of the welcoming experience? What medical procedure wouldn’t be received by patients more positively if certain escapist rituals were introduced to help patients prepare for surgery? (Take a cue from refractive eye surgeon Roy Rubinfeld of Washington Eye Physicians & Surgeons in Chevy Chase, Maryland, who joins staff and patient in a shot-glass toast of carrot juice before entering the surgery room!) The suggestion of adding entertainment value to the experience should not be construed as wanting to turn every doctor into Patch Adams; in moments of life and death, however, it often pays to lighten up. (Recall Ronald Reagan’s comment in the hospital after being shot: “I forgot to duck.”)

Consider finally the big business of professional sports. Many franchises have had new stadia built to improve the esthetic value of the fan experience. Scoreboards offer greater entertainment. League websites are replete with searchable and sortable statistics that fans actively explore to learn how their teams and favorite (or fantasy) players are doing. Successful teams not only pack in the crowds at live games but also generate revenues from electronic broadcasts and online subscriptions. To no one’s surprise, the New York Yankees lead the way, not only with its new Yankee Stadium but also with its YES cable network. What’s next in creating new revenue streams? Consider how new escapist experiences might be welcomed by diehard fans. Teams generate revenue from ticket sales for home games as well as advertising sales on broadcasts of away games enjoyed from home. Maybe there’s a third-place opportunity for sports. Couldn’t some teams charge fans to come to a facility designed explicitly for watching away games? On occasion, teams allow fans to watch away playoff games in home arenas. But these venues are built for taking in live events and not mediated action. Like LAN parties, third-place arenas for away games could mix some of the excitement of being together with other fans with access to certain technological interactions with games that simply are not available from home. The design of such experiences should aim to offer distinctive new places for experiencing away games.

When all four realms abide within a single setting, then and only then does plain space become a distinctive place for staging a new or improved experience. Occurring over a period of time, staged experiences require a sense of place to entice guests to spend more time engaged in the offering. Time-conscious consumers and businesspeople want to spend less and less time with providers of goods and services, who seem all too willing to oblige. Think of fast-food chains and corporate call centers striving to minimize the seconds per service transaction. The obvious destination: not spending any time with customers, who learn to spend their time elsewhere. That is the prevailing attitude in banking, for example, an attitude that led directly to widespread commoditization.

So where will your customers spend their hard-earned time? In places deserving of more time, where people can simply be, go and do, learn, and enjoy. To understand the nature of such places, consider what turns a house into a home, and turns any space into a place. In Home: A Short History of an Idea, Witold Rybczynski, professor of urbanism at the University of Pennsylvania, examines five centuries’ worth of designed environments, from the Middle Ages to Ralph Lauren Home Furnishings. Among the multiple cultures that Rybczynski examines, he calls particular attention to the desire and ability of the Dutch during their Golden Age to successfully “define the home as a separate, special place.”30 For the Dutch, “‘Home’ meant the house, but also everything that was in it and around it, as well as the people, and the sense of satisfaction and contentment that all these conveyed. You could walk out of the house, but you always returned home.”31 In such Dutch homes, furnishings strictly revolved around the use of each room, thereby defining the sense of place. Outside the home, gardens and other landscaping—however modest, given Holland’s relatively small size—skillfully signaled the passage from the plain space outdoors to the distinctive place indoors. Such welcoming formed the basis for communing with family and friends.

The sweet spot for any compelling experience—incorporating entertainment, educational, escapist, and esthetic elements into otherwise generic space—is similarly a mnemonic place, a tool aiding in the creation of memories, distinct from the normally uneventful world of goods and services. Its very design invites you to enter, and to return again and again. Its space is layered with amenities—props—that correspond with the way the space is used, and it is rid of any features that do not follow this function. Engaging experiences bring these four realms together in compelling ways. We’ve already mentioned edutainment as one combination of realms aimed at achieving a certain experiential aim:

Edutainment = Education + Entertainment (holding attention)

Consider, too, the five other dimensions of an engaging experience that emerge from combining realms:

Eduscapist = Education + Escapist (changing context)

Edusthetic = Education + Esthetic (fostering appreciation)

Escasthetic = Escapist + Esthetic (altering state)

Entersthetic = Entertainment + Esthetic (having presence)

Escatainment = Escapist + Entertainment (creating catharsis)

The terms vary in how trippingly they fall from the tongue (although edutainment flows smoothly, primarily through familiarity and repetition), but each maps out rich territory for understanding how to set the stage for compelling experiences.32 Holding attention, changing context, fostering appreciation, altering states, having presence, and creating catharsis—these lie at the heart of orchestrating compelling theatrical performances. When every business is a stage, these states need to be mastered.