CHAPTER 4

What’s in Your Bags?

We all have baggage. You know, that stuff we carry around with us that came from past experiences. The “funny” thing is, these experiences are so ingrained in our brains that we don’t even notice them. Did you ever have the experience of being with someone new, and they did something so heinously odd that you just had to say something? You know, like eating pastrami on white bread with mayo. It’s just not done! Everyone knows that pastrami is eaten on rye with mustard—period! But for the “offending” person requesting two slices of white and a healthy slathering of mayo, they are acting completely normally. It’s all how you look at your experiences and beliefs.

There’s an old expression that rolls around in my brain from time to time, along with so many other axioms, words of wisdom, and sayings: A watched pot never boils. Of course, this saying is entirely incorrect. The pot will boil, provided there’s a fire underneath; it’s just a matter of enough heat and patience.

We grow up with all sorts of beliefs that have been injected, absorbed, and assimilated into our subconscious. They become a part of our idea of normal, whether or not they are actually correct. Take, for example, this conversation between a couple we’ll call Ilene and Eric. Ilene grew up in a family in which money was not especially plentiful, and survival was on the top of the list. Eric grew up in a more affluent family in which money was much more available. When I asked them each to talk about what is important to them in building a financial future, here’s what I heard.

![]()

Eric: “I would like to build a reserve fund to provide a safety net for our children. I don’t know how to quantify it, but I am afraid that they will not be able to find careers that will afford them a suitable living. My parents were there for me while I found myself. I would like to be able to give them a down payment on a house.”

The look in Ilene’s eyes bespoke complete disbelief in what she was hearing. Respectfully, she held her tongue until it was her turn to share her thoughts.

Ilene: “I grew up with a completely different set of beliefs. My parents expected that my siblings and I would live a lifestyle that our salaries could afford. I understand a safety net of sorts—such as, if they have difficulty, they could move back home until they could afford their own place. But the idea of supporting a lifestyle that they couldn’t sustain on their own doesn’t seem to be doing them any favors. Oh, and by the way, your parents didn’t give us the down payment; we paid back every nickel.”

![]()

Without going into the rest of the conversation, this example illustrates how different experiences create different beliefs. Unless we challenge our experiences and ask some very important questions, we will continue under our current beliefs unabated. If our beliefs and habits are destructive, there’s a better than even chance that the conclusion will not be pretty.

In this chapter, you will explore what keeps your head off the pillow at night and why, and you will also explore what would allow a good night’s sleep without financial worry. You will read a wonderful story called “The Pickle Jar” that illustrates how simple money habits can reflect deep core values. And finally, you will have the opportunity to think about possible small steps to help you begin to move in the direction that would be like that warm cup of chamomile tea before bed—ahhhhhhh.

What’s Your “Pillow Factor”?

We all have restless nights every once in awhile. Maybe it was that cup of coffee late in the day or that caffeine-packed chocolate brownie for dessert? For those whose mornings arrive as a rescue from a night of uncontrollable worry and stress, recognize that the cause of the sleeplessness was not food-based. For those who are dogged by bill collectors, threatening letters, or just the knowledge that your financial house is not secure, it is a night of misery that you know will just repeat itself the next night. It’s a terrible cycle. All you want is to have a level of comfort with your financial life that puts you more in control. What factors and circumstances have led to your current feeling of unease? What beliefs do you hold that might be in need of a second look?

One way to examine your level of comfort is to measure your comfort level with your financial life. I call it your “pillow factor.” In other words, what keeps your head off the pillow at night, or what allows you to sleep peacefully?

We are experts at the irrational. We make decisions based on our beliefs or on what we believe we should do, even at the cost of what we know is good sense. There are great resources available that demonstrate this wonderfully: Sway by Ori and Rom Brafman, Predictably Irrational by Dan Ariely, and Your Money and Your Brain by Jason Zweig, to name a few. A richness of great works is available to help you deepen your understanding, and let’s face it: Without understanding, you’re going exactly nowhere.

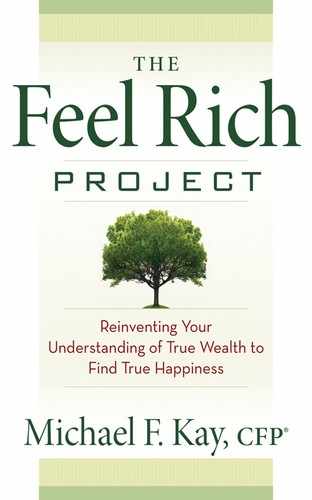

Time for a short exercise. Worksheet 4-1 provides a great opportunity to do what is referred to as a “Ben Franklin.” Do you know what that means? It’s also known as a “T-account.” For those of you who ever took a basic accounting course, you know all about T-accounts. For those who have never had the pleasure, in bookkeeping and accounting, a T-account is used to understand the impact of transactions on various types of accounts.

The T-account allows for an understanding of transactions, the plusses and the minuses. Benjamin Franklin used it to help make decisions by recording the pros and cons of a particular issue. Here’s an example: Say the issue is whether to spend $5,000 on a vacation. The pros might be you will have time with those you love, you will have fun, you will get a much-needed break from work, being in the sun has certain health benefits, and you get to recharge your batteries to be more creative and effective at work when you get back. The cons: It will put a strain on your budget and leave you in more debt. It will be stressful knowing there will be a bill coming. Okay, there’s your T-account. In evaluating a decision, you must weigh the pros and cons against what you value most. What solutions might you come up with? Do you see how this tool could help in considering more objectively challenges that confront you?

Try to do this exercise in one sitting when you have some quiet, uninterrupted time. Don’t filter your thoughts; there will be time for that later. Write as quickly and as thoroughly as possible without taking a break. Take a few deep breaths and clear your mind of all the things you need to do. Oh, and please turn off your cell phone! (I bet you didn’t see that coming.) Ready? Go!

WORKSHEET 4-1: WHAT’S YOUR PILLOW FACTOR?

Here’s your opportunity to look at the pros and cons of making the sorts of decisions you’ll need to change your future.

A couple of suggestions:

1. Frame your decision as a question, such as “Should I buy a new computer?”

2. List the pros and cons.

3. Weigh your pros and cons. Which ones are really important and which ones aren’t critical?

4. Think about the tradeoffs you might need to make and add those to the mix.

How was that for you? What did you discover? Did you have any a-ha moments?

You Don’t Know What You Don’t Know

Consider the following statement: You don’t know what you don’t know. In other words, are the areas that create discomfort stemming from areas in which you have no expertise or knowledge? If that last statement was confusing, let me back up a little with a short example.

I bought my first car after I graduated from college and found a job as an accountant. It was a lemon yellow ’vette. Don’t get too excited—it was a Chevette, which even at the pinnacle of its existence was an ugly little box. But it was mine and I was thrilled to own a car. When it came time to service the car with a tune-up and oil change, I figured I could save some money and do it myself. Note to reader: My knowledge of auto mechanics was somewhere below zero. But I figured the guys in high school who worked in auto shop weren’t rocket scientists, so ergo, I got this. I will spare you the gory and gruesome details. Suffice it to say that the cost of fixing what I screwed up far exceeded what it would have cost if I had let the dealer do it to begin with. Lesson learned: You don’t know what you don’t know until you’re knee deep in wires and oil.

Getting back to the idea that we don’t know what we don’t know. This seems to be one of the biggest areas of concern and dissatisfaction. Let’s examine this together because money is one area where lack of knowledge or comfort seems to hold a great deal of weight. There seems to be some confusion about where money knowledge comes from. Some families talk about money and teach important lessons about savings and prudent spending. Others, unfortunately, grow up in households where money is never discussed. Have you ever heard an elderly person share information about the health of someone, and if that person has cancer, the word is whispered at infrasonic levels? Well, for some, money is treated the same way. It might be because talking about money is considered rude or tacky, or that their messages about money is that it’s no one’s business, or that their own level of understanding is low and therefore there is embarrassment in broaching the subject. My statement to you is this: It is vital that you understand where your money beliefs come from, and how it impacts your behavior and habits. But when it comes to the technical sides of financial decisions, there is a whole different level of knowledge that is required.

Take life insurance, for example. Looking at something as “simple” as life insurance as an example of not knowing what you don’t know, think about these questions:

• Do you need life insurance?

• How much coverage is appropriate?

• What risks are you most interested in covering?

• What type of insurance?

• For how long do you need protection?

• What company should you trust?

• By what criteria do you judge a company?

• How will you know if the company is going to fail?

• By what mode should you pay?

• Who should be the beneficiaries?

• If you have children, can they be the direct beneficiaries?

• Can you afford it?

• Can you afford not to have it?

• Should you buy it online or find an agent?

• Who can you trust to provide proper advice?

• What riders are important?

• If you’re buying permanent protection, what dividend options are appropriate?

• What are the underwriting requirements?

Believe it or not, there are several more questions that need to be considered in just this one area. Is there any question why you might be experiencing a high degree of sleeplessness? Where there are unknowns, and you don’t even know the scope of the unknowns, confusion and fear and maybe even shutdown are sure to follow.

Separating Technical Financial Knowledge From Beliefs and Behaviors

So your ability to comprehend the scope of all the financial issues that you need to deal with is less than comfortable. You need to be okay with the idea that if it is something you never learned, you should not expect to be comfortable. But that’s all right: it makes you exactly normal. What we need to do is separate your beliefs and behaviors around money from your technical knowledge. It is vitally important that you work toward a better understanding of you, your money history, your beliefs, behaviors, and habits around money. The technical stuff comes later.

I need you to make the decision to ignore the technical questions that keep you up at night and focus on the behavioral issues associated with your money life. All the technical knowledge in the world is not going to help your money life if you cannot control your spending and cannot change your habits to be more in alignment with your values.

![]()

The Pickle Jar Story

As far back as I can remember, the pickle jar sat on the floor beside the dresser in my parents’ bedroom. When he got ready for bed, Dad would empty his pockets and toss his coins into the jar. As a small boy, I was always fascinated by the sounds the coins made as they were dropped into the jar. They landed with a merry jingle when the jar was almost empty. Then, the tones gradually muted to a dull thud as the jar was filled.

I used to squat on the floor in front of the jar and admire the copper and silver circles that glinted like a pirate’s treasure when the sun poured through the bedroom window. When the jar was filled, Dad would sit at the kitchen table and roll the coins before taking them to the bank. Taking the coins to the bank was always a big production. Stacked neatly in a small cardboard box, the coins were placed between Dad and me on the seat of his old truck.

Each and every time as we drove to the bank, Dad would look at me hopefully. “Those coins are going to keep you out of the textile mill, son. You’re going to do better than me. This old mill town’s not going to hold you back.” Also, each and every time, as he slid the box of rolled coins across the counter at the bank toward the cashier, he would grin proudly and say, “These are for my son’s college fund. He’ll never work at the mill all his life like me.”

We would always celebrate each deposit by stopping for an ice cream cone. I always got chocolate. Dad always got vanilla. When the clerk at the ice cream parlor handed Dad his change, he would show me the few coins nestled in his palm. “When we get home, we’ll start filling the jar again.” He always let me drop the first coins into the empty jar. As they rattled around with a brief happy jingle, we grinned at each other. “You’ll get to college on pennies, nickels, dimes, and quarters,” he said. “But you’ll get there. I’ll see to that.”

The years passed, and I finished college and took a job in another town. Once, while visiting my parents, I used the phone in their bedroom and noticed that the pickle jar was gone. It had served its purpose and had been removed. A lump rose in my throat as I stared at the spot beside the dresser where the jar had always stood. My dad was a man of few words and never lectured me on the values of determination, perseverance, and faith.

The pickle jar had taught me all these virtues far more eloquently than the most flowery of words could have done. When I married, I told my wife, Susan, about the significant part the lowly pickle jar had played in my life as a boy. In my mind, it defined, more than anything else, how much my dad had loved me.

No matter how rough things got at home, Dad continued to doggedly drop his coins into the jar. Even the summer when Dad got laid off from the mill and Mama had to serve dried beans several times a week, not a single dime was taken from the jar. To the contrary, as Dad looked across the table at me, pouring catsup over my beans to make them more palatable, he became more determined than ever to make a way out for me. “When you finish college, Son,” he told me, his eyes glistening, “you’ll never have to eat beans again—unless you want to.”

The first Christmas after our daughter Jessica was born, we spent the holiday with my parents. After dinner, Mom and Dad sat next to each other on the sofa, taking turns cuddling their first grandchild. Jessica began to whimper softly, and Susan took her from Dad’s arms. “She probably needs to be changed,” she said, carrying the baby into my parents’ bedroom to change her diaper.

When Susan came back into the living room, there was a strange mist in her eyes. She handed Jessica back to Dad before taking my hand and leading me into the room. “Look,” she said softly, her eyes directing me to a spot on the floor beside the dresser. To my amazement, there, as if it had never been removed, stood the old pickle jar, the bottom already covered with coins. I walked over to the pickle jar, dug down into my pocket, and pulled out a fistful of coins. With a gamut of emotions choking me, I dropped the coins into the jar. I looked up and saw that Dad, carrying Jessica, had slipped quietly into the room. Our eyes locked, and I knew he was feeling the same emotions I felt. Neither one of us could speak.

![]()

Ah, our values—our real values—not the ones that we tell ourselves are important, but those that reside deep within our hearts. “The Pickle Jar” is a great example of applying values to real action. In this case, the values created a set of beliefs, behaviors, and habits that supported that value. Technical knowledge and comfort did not play a part in building success. Many people value education, and therefore putting money away for their children to attend college sits very high on the list. They might get trapped in trying to analyze every possible 529 plan and do nothing, or they might start putting money into a savings account. You do not need a PhD in financial planning to create actions that bring you in alignment with your values. (In the next chapter we will explore your values or what I call, your musts.)

Rethinking Your Financial Discomforts: Getting to the Whys

Let’s go back to the areas that create stress and those that create comfort. As you examine your pillow factor, uncover the areas that create stress or discomfort in your money life. We want to create a juxtaposed position in your thinking. For example: If you have difficulty controlling your spending, try to understand where this came from. What were the circumstances in your past that lead to difficulty in keeping the dollar in your pocket or the credit card in your wallet? If you think about this, you will most likely be able to draw a straight line between what you heard, saw, or experienced and how you act today.

People who grew up during the Depression generally fall into two categories: Either they will not part with a dime, or they are inveterate spenders. Their experiences create the pattern for their beliefs, behaviors, and habits. Some were so pained by their experience that fear took over making spending very painful; a “just in case” attitude took over. Others wound up bathing themselves in things to soothe the lack they once experienced.

I remember, vividly, my parents fighting bitterly about money. My father, a child of Depression, was hard-pressed to part with a nickel. My mother, 11 years his junior, was not a Depression child and had a completely different experience when it came to entitlements. It wasn’t pretty. It took a long time for me to understand why I had a stomachache anytime the discussion of money was raised.

For some people, the idea of being able to spend freely is associated with how they feel about themselves and their self-esteem. For some, it might be that at one time in their life, they experienced lack and now they refuse to feel that pain of not being able to “have.”

The idea here, and as demonstrated in “The Pickle Jar,” is that it’s about small change or small changes. But before you can approach the idea of change, you have to, as Simon Sinek put it, “start with why.” You must define why you do anything; without this understanding, you are a rudderless ship untethered and uncontrolled by meaningful destination. It’s a lousy way to live your life.

Let’s connect the dots here.

• Our beliefs create our behaviors, and our behaviors create our habits around money.

• We may be either worriers or avoiders, which creates a pathway to either no decisions or less than optimal choices.

• Though we might have great discomfort around money and financial matters, there are simply too many issues to feel a sense of comfort—so we either do what is convenient or we do nothing. An example of that might be signing up for employer-sponsored life insurance and believing that it is sufficient or failing to increase your 401(k) contributions as your salary increases.

• We generally do not take the time to really think about or talk about our values. But by making that effort, we create a set of “rules” that become our guideposts.

• With every decision you make, you are either moving closer to or further away from living your values.

Let’s try an exercise to start replacing negative behaviors with thoughts of more positive ones. Doing so can help you to think about how to make small, meaningful changes to improve your financial life and live your values.

In Worksheet 4-2 make a list of your current behaviors that keep your head off the pillow. For example:

1. I spend every penny I earn.

2. I don’t think about how much I spend.

3. I have a high balance on my credit cards.

4. If I lose my job I cannot survive without outside help for more than a month or two.

Now, replace those behaviors with more positive messages. For example:

1. I would feel more at peace and comfortable if I was saving on a regular basis.

2. I carefully apportion my income to cover my needs and to provide for a secure future.

3. I live debt-free and have no pressure when the monthly bills come in.

4. I have a rational emergency fund saved that can see me through nine months of living while I transition into a new opportunity.

Time to get going on worksheets 4-2 and 4-3. Worksheet 4-2 will help you look at your current thoughts and likely replacements. Worksheet 4-3 is designed to help you organize your thoughts, and begin to align what is really important and what life is likely to look like if you don’t.

Take all the time you need to get your thoughts together, and attack each question and topic as thoroughly as possible. You might find you will go back and add more thoughts, similar to your mind map from Chapter 3. That’s great work!

WORKSHEET 4-2: REPLACING NEGATIVE BEHAVIORS WITH POSITIVE THOUGHTS

List your current negative behaviors:

1.

2.

3.

4.

Now think about how you can turn these negative behaviors into positives:

2.

3.

4.

You need time, space, and focus to make this real and meaningful.

Once you’ve accumulated your list of replacement behaviors or guidelines, start to think about what small steps that you can take to move you in the right direction.

WORKSHEET 4-3: ORGANIZING YOUR THOUGHTS

Use your responses from Worksheet 4-2 to fill in the blanks here. The goals are to organize your thoughts and to begin to envision a new plan to move you forward.

• What do you need to stop doing?

• What do you need to start doing?

• Why is it mega-important that you do this?

• What is the cost of not changing?

• What will your life look like if you remain as is?

• What can your life look like if you make meaningful small shifts in your life that are aligned with your values?