5

Financial position

What topics are covered in this chapter?

- Why financial position is critical

- What is the company’s financial position?

- Gearing – the debt/equity ratio

- Pension deficits and other liabilities

- Interest cover and other measures of financial strength

- Credit ratings

- Covenants

- Why high gearing may hurt the company and its share price

- How much debt should the company have? Efficient balance sheets

- Raising fresh capital: rights issues

- Cash flow

- Summary

- Checklist

Why financial position is critical

As the current financial environment has made abundantly clear, the level of debt in a company (often referred to as ‘gearing’ or ‘leverage’) is a key element of risk – and, as we have seen, financial risk is a key driver of valuation. One of the key lessons from the credit crunch is that while debt is fine when the economy/business is doing well, when the economy slows down then it can be disastrous for certain sectors.

Financing businesses with debt became widespread during the boom years of 2004–07. Indeed, the advantages of using debt were seen to be so obvious that the private equity sector grew considerably while using debt aggressively, while the company sector, often under pressure from private equity or shareholders wanting more efficient balance sheets (see p. 185), engaged in massive share buy-backs.

Similar to when you buy your house with a very large mortgage (so you can buy a bigger, more expensive property) the impact on our wealth is dramatic if house prices rise significantly. If we buy a house for £500,000 financed entirely with a mortgage, a 20 per cent price rise generates a £100,000 profit. Provided we sell while house prices are still rising this is all very easy and profitable. So in an economic environment of strong growth and, crucially, rising asset prices, funding businesses with debt delivered very strong results. Importantly, it is vital to remember that this is a function of strong economic and asset growth and debt funding – not individual brilliance – because, as they say, a ‘rising tide lifts all boats’.

Of course if the economy turns down things can become very challenging very quickly. Rising interest rates – or the absence of credit, which has characterised this recession but has the same effect – not only slows the economy but also reverses the trend in asset prices. This causes havoc with balance sheets for the personal and corporate sector, as we have seen. The ‘toxic assets’ consisting of asset-backed loans to housing and commercial property have been a crucial component of the problems facing the banks. At the company level there is a similar exposure to economic activity although there may be lots of other risks to consider as well – the impact of competitors, imports and exchange rates, dependence on certain customers, etc.

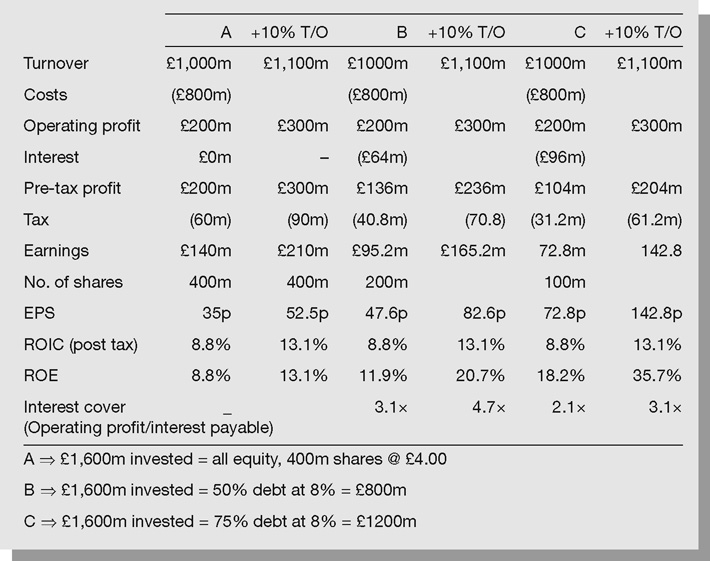

Figures 5.1 highlights the advantages to earnings and return on equity of funding a business with debt. And of course as debt is cheaper than equity it will, on the face of it, be much easier to create shareholder value. However, as Figure 5.2 makes clear, if things turn down the highly geared companies are in trouble very quickly.

In the figures we have three identical businesses that have chosen three different funding options. To illustrate operational gearing and for simplicity we assume all costs are fixed. Company A is funded with 100 per cent equity while B has half equity and half debt, and C has funded the business with 75 per cent debt. As we can see, company C has much higher earnings per share (as there are far fewer shares in issue) and much higher return on equity. It is also worth noting, given the tax-deductibility of debt, how company C is paying about half as much tax as company A.

Figure 5.1 Debt and equity funding – the upside

It is when turnover rises 10 per cent that we can see the even greater ‘benefits’ of the high gearing. Earnings for company C almost double compared to a 50 per cent uplift at company A. Interest cover for company C also expands to a healthier 3.1×. So if the turnover continues on an upward trend the debt-funded business will continue to enjoy better earnings growth and returns on equity.

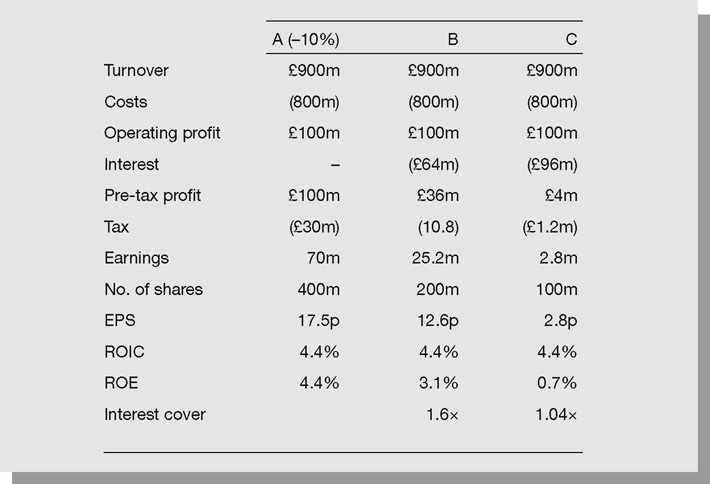

However, as Figure 5.2 shows, if turnover comes under pressure for whatever reason then company C is suddenly in real difficulty. A 10 per cent reduction in turnover almost eliminates pre-tax profit (and hence earnings) as all the operating profit services the interest bill. Interest cover falls to just over 1.0×. Therefore debt is excellent if everything is going well!

Figure 5.2Debt and equity funding – the downside

So when considering the financial position of a company it is critical to establish the type of business it is and the risks it is likely to face. As Figure 1.1 shows, certain sectors are very sensitive to the movements of interest rates (or in the current situation the availability of credit) and the subsequent impact on the economy.

Similarly, as Figure 5.2 shows, the impact of operational gearing – that is to say the impact when turnover falls on profits when fixed costs are high – is also pretty devastating. Combining high debt with a company sensitive to economic forces and high fixed costs is a recipe for disaster – as was well illustrated by the plight of the automotive and airlines sectors as well as banks, housebuilders and construction companies.

With companies going bust or needing rescue rights issues, the risks of financing certain types of business with debt all too apparent. You need to pay attention to the amount of debt in a business (and whether the business profile will support that debt) – but also the type and term structure of debt (i.e when does it have to be paid back?). If all the debt has to be paid back within (say) the next 12 months and banking conditions are unfavourable the company may run into trouble. This is a far riskier proposition than companies with a long-term debt maturity profile with money being paid back evenly over the next decade (and preferably much of it owing at the end of that period). The company having to pay back debt may have to sell off key assets at less than favourable prices (because no one else is in a very strong position to fund the purchase of the assets) to stay afloat.

The other key area to focus on is the fact that the interest bill is paid out of cash flow. Without cash flow the game is up as the debt cannot be serviced. The company may have a reasonable asset backing but if those assets are not generating cash then covenants, many of which will be linked to interest cover or the performance of EBITDA, are likely to be broken. This will almost inevitably mean that the dividend will be cut as this is also paid out of cash flow and the banks may well stipulate that this be suspended until they get their money back.

Furthermore, given that our main concern is the competitive position of a business, a company with a lot of debt may not be investing in its product offering and reducing its costs. Decisions will be distorted as it focuses on running the business for cash to stave off the banks rather than serving customers effectively in the short and long term. Clearly this is not sustainable in the medium term. And as the company loses its market share it will be making less money to service the debt, let alone invest in the business.

Therefore getting to the bottom of the company’s financial position and its cash flow profile is crucial to minimise the risks in investing and to ensure you are investing in a sound business with long-term potential off the back of a strong competitive position.

What is the company’s financial position?

There are a number of key figures to look at when considering the financial health of a company:

- gearing – the debt/equity ratio

- pension deficits and other liabilities

- interest cover and other measures of financial strength.

Gearing – the debt/equity ratio

Gearing is the most common way of measuring a company’s financial position. The normal way to derive this is to first work out the group’s net debt. Net debt is the total debt a company has minus any cash it holds. You then divide that figure by shareholders’ funds. Shareholders’ funds are clearly listed on the balance sheet and are basically the book value of the company’s assets at that point in time. This would include the value of buildings and plant, stock held and any profits retained over the years. A common definition of gearing is net debt/shareholders’ funds, the latter including minorities (although some investors may exclude minorities which gives a more prudent view). Minorities are the portion of assets owned by outside shareholders when a company has a majority holding but does not own 100 per cent of the company.

You then multiply your answer by 100 to give you the gearing figure, expressed as a percentage. So if net debt is £100 million and the company’s shareholders funds are £200 million, the company is said to have gearing of 50 per cent.

Gearing, then, is a measure of how much of the capital employed in the business is provided by shareholders’ funds and how much by debt. A company with low gearing has a small proportion of its capital supplied by debt, whereas a highly geared company has a high proportion of its capital funded by debt.

Companies that are in sectors where there are few fixed assets or where assets tend to be ‘intangible’, such as the value of brand names, can be disadvantaged if you look just at gearing to evaluate their financial position. The same is true of highly acquisitive companies that write off a lot of goodwill on the ‘assets’ they acquire. These companies will tend to have a high level of gearing even if they have very little debt. In these cases a better guide to the companies’ financial position would be to look at interest cover (see p. 177).

There is no ‘correct’ level of gearing (as it depends on the type of business), but above 50 per cent is normally considered on the high side. A company operating in a stable industry, with a clear view of its revenues and little need for new investment in the business, will be able to live with a much higher level of gearing than a company in a cyclical business that has no visibility in its revenues (i.e. it is extremely difficult to predict the volumes and prices of the company’s output) and needs a lot of cash to update a large factory or piece of equipment.

The main questions to ask are:

- How is the company affected by the economic cycle?

- How predictable is the revenue?

- Does the company have pricing power?

- Is the company dependent on one client?

- How much cash is the company generating?

- Does the business need a lot of investment?

- Is the interest rate charged on the debt fixed or variable?

- Is the debt short or long term?

- Are the shareholders’ funds (assets) realistically valued?

Example – calculating gearing

Milk Pops

Let us take another fictional company, Milk Pops, which produces breakfast cereal. We assume it has debt of £60 million, shareholders’ funds of £100 million, so it would be said to have gearing of 60 per cent. Milk Pops has total sales per year of £200 million and a 10 per cent operating profit margin, so its operating profit is £20 million. One of the features of the business is the predictability of its sales, which have grown consistently at around 4 per cent per annum even in periods of recession.

| Debt | £60m |

| Shareholders’ funds | £100m |

| Gearing calculation | |

| Debt/shareholder funds | 60/100 |

| Gearing | 60% |

| Total sales | £200m |

| Operating profit margin | 10% |

| Operating profit | £20m |

Full Stop

Compare that with Full Stop, a fictional brake-unit manufacturer that makes brake units and sells them to a nearby large car manufacturer. Full Stop also has debt of £60 million and shareholder funds of £100 million and so like Milk Pops has gearing of 60 per cent. Its sales are currently £150 million, having fallen from £200 million last year. Its profit margin is 5 per cent, having fallen from 10 per cent last year. This year its operating profit is £7.5 million.

| Debt | £60m |

| Shareholders’ funds | £100m |

| Gearing calculation | |

| Debt/shareholder funds | 60/100 |

| Gearing | 60% |

| Total sales | £150m |

| Operating profit margin | 5% |

| Operating profit | £7.5m |

A key feature of this business is that it is highly cyclical in nature (as demand for cars goes up and down with the business cycle). In addition it is vulnerable to the loss of one major contract with a car manufacturer. This raises uncertainty over its future performance.

Analysis

While the two companies both have relatively high gearing it is evident that Milk Pops has a higher level of operating profit and a more stable performance than Full Stop. Full Stop has the same relatively high debt but makes less money, less consistently. This would be likely to cause concern for investors.

When does the debt mature?

Another step, especially relevant in the current environment, is to check the ‘term structure of debt’ – that is, when does the debt mature? Ideally the company should have debt maturing in a number of years’ time as a reliance on short-term debt may make renegotiating that debt difficult and expensive if it is all due to mature in (say) the next six months.

Pension deficits and other liabilities

To get a comprehensive view of the debt profile of the company as well as looking at the level of short- and long-term loans (less any cash on deposit or cash-like investments) we need to check any other liabilities the company may have responsibility for. Here we need to examine pension and health care liabilities, off-balance sheet debt, and outstanding preference and convertible shares. The new IFRS accounting standards mean all these are now recognised as debt and the credit rating agencies also factor them into their assessment of a company’s rating.

Pension fund deficits

The importance of pension fund deficits in corporate valuation continues to dominate the headlines. According to the Pension Protection Fund in the UK, the insurance scheme for the underfunded pension plans of insolvent employers, the aggregate gap between the value of scheme assets and the value of liabilities it guarantees rose to £253.1 billion.

The arrival of IFRS brings the issue to the fore as the impact of deficits will be felt directly on the balance sheet. This will affect the net assets of the business through distributable reserves and hence dividend-paying capacity. In effect this makes explicit the fact that shareholders are exposed to risk through pension guarantees to current and previous employees. The company’s financial position is very much weakened as the deficits are treated as debt.

Crucially, the funds required to make good such promises (and they are often substantial) are funds diverted from the potential income of investors (dividends are being cut as a result of this) or funds potentially invested in the business which help maintain and enhance the company’s competitive position. Clearly both of these drastically undermine the attractiveness of the company as an investment. Similarly, there have been situations where companies looking to reduce their debt through disposals have discovered that the pension fund trustees have a say in how the disposal proceeds are used – and clearly it may be their legal duty as trustees of the pension scheme to insist that the funds make good a deficit.

The accounting for pension funds was also put under the spotlight by a Securities and Exchange Commission enquiry into the assumptions made by US firms on the expected returns from shares. The higher the assumed returns the lower the deficit and the less the need to pay into the fund. As a result earnings benefit or are manipulated. Some companies have been assuming equity returns as high as 10 per cent. The wisdom of doing this when such a high rate has never been delivered over a sustainable period is clearly questionable – let alone given the actual return from equities in recent years.

As well as the ‘flexibility’ of assumptions on expected returns, the other variable that can influence the size of the deficit is the discount rate used. The lower the rate the greater the liability (as future liabilities are discounted to present value at a lower rate) – this may lead to companies choosing a higher rate to lower the deficit. So the choice of discount rate is actually very important. With ‘quantitative easing’ seeing long-term gilts rise in price (and yields correspondingly fall) this can have serious repercussions for the size of the deficit.

The other key assumption is how long the liabilities will run for – i.e. how long will the pensioner live? These longevity assumptions can make a dramatic difference to the size of deficit as the company’s liabilities are running for much longer. It was estimated that Boots’ pension fund deficit would increase by about £350 million if longevity assumptions were changed by three years.

Another aspect that needs to be considered is the asset allocation of the pension fund. The extra volatility of shares as an asset class introduces uncertainty as to returns, and with the introduction of the new IFRS accounting standards this will be evident on the face of the P&L. The risk of this equity exposure and the associated extra volatility results in a higher cost of capital. At the company-specific level companies such as BT and Diageo have high equity exposure within their schemes.

Therefore when assessing the value of a target company the pension fund deficit has to be incorporated into the enterprise value (see p. 273) – the deficit is effectively a liability akin to debt. This is reinforced by the fact that the credit rating agencies take the liability into account when attributing ratings. The link has been made explicit by the bond issues made by many companies (including the largest ever, GM’s $13 billion capital raising) deliberately undertaken to plug a hole in their pension funds. In the UK, Marks and Spencer has also issued a bond specifically to help fund its pension fund deficit.

Sectors susceptible to deficit problems have the characteristics of being mature and labour intensive and often have been government-owned enterprises in the past. Periods of heavy redundancies/early retirements may also create liabilities. Accordingly engineering, automotive, national airlines, brewers, utilities, fixed-line telecomms and support services are sectors where care needs to be taken.

With recent returns from equity markets being so disappointing, companies undergoing ‘triennial reviews’ of their pension funds’ capacity to service future liabilities are likely to see a big mismatch between assets and liabilities. Smiths Group warned (on 24 March 2009) that it may see its contributions rise significantly as it undergoes its review. Its deficit has risen from £11 million to £500 million. On the day it announced this 14 per cent was knocked off the share price. Formerly nationalised businesses such as BT and BA have significant deficit issues as well. BT could be forced to double its annual pension contributions to £560 million a year under a legally binding agreement it signed with the trustees of its pension scheme in 2006 and approved by the Pensions Regulator. BA has on paper a £600 million deficit and is paying £320 million into the scheme – this is a considerable increase in risk given the company’s debt profile and high operational gearing. The probability of its dividend being restored looks very slim on that basis.

One of the key issues has been the deterrent effect the pension deficit has on deals. The deficit is increasingly appreciated as a debt obligation and can add considerably to the take-out value for the deal. This happened in Permira’s proposed acquisition of WH Smith. Similarly, uncertainty over the extent of pension liabilities was an issue in Philip Green’s bid for M&S. On the other hand, one of the reasons Balfour Beatty could take over Mansell was that it had the resources and financial strength to absorb its pension liabilities. Mansell was concerned it would not have the resources both to meet this liability and fund the growth of the business.

Health care liabilities

Another area of particular importance, especially in the US, is the company’s liability for the health care of its employees (past and present). Again assumptions made on the inflation of health care costs and the discount rate used will have a big impact on reported earnings. For the domestic US automotive companies the cost of health care per car is often greater than the cost of steel per car (this is true for both GM and Ford). As well as being a liability that needs to be taken into account when computing economic value, it clearly has a profound impact on the company’s economic competitiveness. Many overseas players without such heavy ‘legacy’ costs are therefore far more competitive. It may also mean that given the need to service these ‘interest’ or liability expenses there is a temptation for the US producers to go for volume to generate cash – hence the discounting in the new car market although the fixed-cost nature of the business also suggests there may be a tendency to go for volume too.

The inevitable impact on margins from such a volume-led strategy (the US majors make very little (if anything) from manufacturing cars) will also heavily influence valuation. Similarly, a poor competitive position undermines the credit ratings of the companies. Interestingly, both S&P and Fitch cited pension and health care deficit concerns (and the risks to the projected returns being used given the actual performance of equity markets) whenever they downgraded GM’s debt.

A company’s liability to its employees in terms of both pensions and health care is a major financial issue. With shareholders shouldering this responsibility it must be factored into valuation. As we have seen with the US car sector, these liabilities really affect the competitive position of the firm and therefore the attractiveness of the company as an investment. The treatment of these liabilities as debt also raises profound questions when examining the appropriate financial structure for a company. These have been very real concerns for some time but the arrival of IFRS accounting standards will crystallise the issues for investors, lenders and dealmakers alike.

Off-balance sheet debt

It always pays to make sure that the company has declared the full extent of its liabilities and that this is incorporated in the debt number. The company may have debt in a joint venture that is not consolidated in the overall debt numbers. This is referred to as off-balance sheet debt. Similarly, the company may have leasing obligations that are, in effect, debt.

The use of off-balance sheet debt was of course a major feature of the demise of Enron, the energy trader. The company flattered its balance sheet by parking debt off balance sheet in joint venture companies. These companies were set up specifically to conceal the debt. An important lesson from this saga was that the off-balance sheet companies had assets equivalent to their liabilities. These special purpose entities (known as special purpose vehicles or SPVs or in the financial services area as structured investment vehicles or SIVs) therefore had gearing of 100 per cent. It can be difficult to unearth this information, but a close look through the notes to the report and accounts is crucial in order to find related-party transactions and liabilities.

The banks have had many of these SIVs which were not apparent to investors as they were not on the balance sheet. However, they were classified as liabilities when things got difficult. Some consider this one of the major regulatory oversights of the banking crisis.

Convertible and preference shares – also debt?

When looking at the gearing ratio you should also consider whether the company has any convertible shares or preference shares that may be to all intents and purposes debt. This may be because the shares are redeemable or will never become equity. Many companies will exclude these from their gearing figures, which gives a much more flattering view of their financial position. Most analysts will treat these as debt and this will give a more conservative view of the financial position.

It is always worth taking a cautious view of overall indebtedness and being as comprehensive as possible in assessing the debt number.

Short- and long-term debt

An important issue to bear in mind when looking at a company’s financial position is the maturity structure of the debt as well as the overall level. If it is all short-term debt at variable rates of interest, profits will be hit hard if interest rates rise sharply. Also the banks may call in the debt when it is up for renewal rather than extending it, which could cause other lenders to panic. Longer-term debt at fixed rates will offer a more stable financial profile. The impact of changes in short-term interest rates would be minimised and there would be no need for constant refinancing. This would also allow for greater stability, liquidity and flexibility than shorter-term debt.

The other important thing to consider in terms of the time profile of the debt is the assets that the debt is used to finance. If the company has invested in factories and capital equipment that have a long economic life, it would be inappropriate to finance this with potentially volatile short-term debt. Debt of long-term maturity or a bond would be far more appropriate (with bank loans and overdrafts funding short-term working capital requirements). It is not dissimilar to buying a house: a mortgage over 25 years is infinitely more appropriate than an overdraft. You could argue that very long-term assets should be financed with equity.

An aspect of the credit crunch and the lack of finance available from the banks is the extent to which companies will now issue more long-term bonds to fund the business rather than loans or overdrafts from the banks.

The valuation of assets and shareholders’ funds

When you have got to grips with the level of debt, you need to ensure that the value of shareholders’ funds is appropriate. In most instances this should not be a problem. However, there are situations where the assets on the balance sheet might be considerably overvalued, such as where an acquisition has been bought at the top of the cycle at a very high price. If the industry then turns down and remains in the doldrums for some time, the value of the asset is likely to be overstated. If the performance of the business has fallen by 40 per cent and the likelihood for improvement is limited, in theory the value of the asset should be 40 per cent lower. It could of course be worth even less, subject to how overpriced the acquisition was in the first place.

A very important aspect of asset valuation at the moment is the valuation of housing and property assets. Banks having made loans to fund the purchase of these assets (or invested in securitised portfolios of assets) may inherit assets which are worth considerably less than the outstanding loan amount if the consumer or company defaults. So the asset backing of banks with big exposures to housing and commercial property may be considerably less than the current book value. Clearly in this case the shareholders’ funds are considerably overvalued.

Similarly, if we take the situation where an acquisition accounted for 50 per cent of assets and those assets, following an ‘impairment review’, are deemed overvalued by 50 per cent, this 50 per cent falls to 25 per cent, while the overall assets fall to 75 per cent. Gearing on this basis would rise dramatically. If the stated gearing is 60 per cent, then on the basis of the real value of the assets this rises to 80 per cent (60/75). Crucially, because the impairment review is done on the back of lower cash flow projections there is a lot less profit and cash flow to service the debt.

An obvious way of checking whether the assets are appropriately valued is to check the return on assets (the assets are worth only what they are generating in terms of cash and returns on investment). So if the return on assets is 5 per cent and has been for some time, the assets are likely to be overvalued. This may apply to certain divisions or to the whole company.

The asset side of the equation is very important to the companies. Often there will be net asset covenants which stipulate that assets should not fall below a certain level or gearing must not exceed 100 per cent. In this situation the temptation is to maintain an asset base as high as possible. The reality of the worth of the assets is clearly very different. Therefore the asset side of the equation is very much worth taking on board.

Interest cover and other measures of financial strength

One of the issues with looking at debt to equity ratios is that the assets may not be generating the income needed to service the interest payments. Other measures of financial strength tend to look at the income and cash flow that is being generated (from that asset base) and seeing how comfortably the company can meet its liabilities. As we have seen with the operational gearing examples, the key here is whether those income and cash flow streams are sustainable.

Interest cover

Interest cover is a measure of how easily the company can pay interest on its debt. This is measured by taking the operating profit and dividing it by the annual interest payments. Both these items are listed in the P&L statement.

Example – the interest cover calculation

Returning to the example of Milk Pops, its debt stands at £60 million and its operating profit at £20 million. Paying 5 per cent interest a year on its debt gives an annual interest payment of £3 million. So, to calculate interest cover we take £20 million (operating profit) and divide by £3 million (interest payment) to give a figure of 6.7. This means that the operating profit could pay the interest 6.7 times over ... and it’s expressed just like that, 6.7∞.

This is a simple to calculate and widely used method of assessing a company’s financial position. As a rule of thumb, figures below 3 are viewed with caution, while those above are seen as safe. One of the advantages of using this measure is that it provides a much more reliable guide to a company’s financial strength than conventional gearing (debt/shareholder funds) when a company has very few assets.

Where a company has few assets

The use of interest cover is particularly relevant in areas of the service economy where there are few assets (‘people businesses’) and situations where assets have been severely affected by the write-off of goodwill. Consumer products companies that have been involved in a series of acquisitions may have written off substantial amounts of goodwill (where the price paid for the deal considerably exceeds assets on the balance sheet). Diageo, the international drinks company, normally presents its financial position through the use of interest cover because a debt to equity measure would be meaningless as considerable amounts of goodwill have been written off – i.e. shareholders’ funds are relatively low, having been reduced significantly by goodwill written off.

How volatile are the operating profits?

As with the debt to equity ratio, the degree of danger in any given ratio depends on the economic characteristics of the business. As the numerator is operating profit, the key issue to focus on is the sensitivity of operating profits to changes in prices and volumes (operational gearing, see p. 219). If we consider the example of the manufacturing company Tin Can, we know from the characteristics of its markets – overcapacity, a commodity product and competition from imports – that prices are likely to be volatile. With turnover of £250 million, a 5 per cent reduction in price will reduce turnover by £12.5 million. With costs fixed, this then reduces profits by £12.5 million (50 per cent) as well.

Similarly, its cost structure, given a high proportion of fixed costs, makes profits highly sensitive to changes in volume.

If we say that operating profits are £25 million and interest payments are £5 million, interest cover is 5∞. However, on a 5 per cent price reduction, profits halve (from £25 million to £12.5 million) and accordingly interest cover falls to 2.5∞. This is falling to dangerous levels. This deterioration is on an all too plausible assumption of a 5 per cent reduction in prices. If prices fell more than 5 per cent and a key contract was lost, the financial position would deteriorate even more sharply. A 10 per cent price reduction would eradicate profits and leave no interest cover at all.

By contrast, for Milk Pops (or Pink Tablet) a stable volume and pricing scenario suggests that the risks are much lower. Accordingly, interest cover ratios could be a lot lower and one would still be comfortable with the company’s financial position.

The danger level for interest cover

Companies with this sort of cover are in a difficult position, especially if operating profits are volatile as discussed above. At 2∞ or below, the company’s bankers will be keeping a close eye on its developments and indeed it may well be that debt covenants (agreements undertaken by the company with its banks) are being broken. This may lead to a downgrading of the company’s credit status and force the company into disposals or a rights issue, or quite possibly both. In an environment as difficult as the current one, it is likely to be only the best parts of the business that will attract buyers. Following the disposals, what is left of the company may not be what originally attracted you to invest. Therefore, when evaluating a potential investment idea, the risks attaching to a company with such a low level of interest cover are very high – it can cost you a lot of money. A simple and effective ratio, such as interest cover, which can be quickly and easily computed, can help you avoid potential disasters.

Cash flow pays interest costs not asset backing

When we looked at the company’s assets we had to consider the possibility that the shareholders’ funds element of the balance sheet was overstated. The assets might be worth far less than their book value. This will inevitably be because the cash flows they are generating are dramatically lower than has been the case historically. But of course it is the cash flows that service the interest costs. Therefore using measures which deliberately take into account the current (and likely future) cash generation of the business is far more effective. The measures cited below are useful because they allow for this.

Cash flow cover – EBITDA/interest payable

A variant on interest cover calculated by using operating profit over interest payable is to compute a cash flow cover. This adds on depreciation and amortisation to operating profit as they are non-cash costs. This obviously means that the cash coming into the business can also be used to meet the interest payments. However, the danger is that funds are diverted from replacement capital expenditure and investing to maintain competitiveness, to servicing the interest. Nonetheless it may be that you wish to take into account the cash flow cover of interest payments.

An important feature to monitor in the calculation is that interest is not being ‘capitalised’ and thus excluded from the interest payable figure. Interest may be capitalised when it is included in the cost of building plant or facilities for long-term use (the interest is treated as an important cost of the development and is therefore included in the total cost of the project, i.e. capitalised). Food retail outlets, property developers and hotels are some of the businesses that may capitalise interest. There is nothing necessarily wrong with this practice, but it is worth monitoring if the company is capitalising interest and it is worth checking how much interest is being capitalised. The cover would then be calculated on the interest the company actually pays to banks as opposed to the amount declared on the P&L.

Net debt/EBITDA

This also looks at the cash flow element but looks at how many times the debt exceeds the cash flow. The higher the multiple (i.e. if debt is say more than four times EBITDA) obviously the more uncomfortable the position. The other issue of course is the predictability or otherwise of the EBITDA – which again takes us back to the type of business.

After the lax lending of the earlier part of the decade banks are now being much stricter on these multiples. Future covenants are likely to limit debt at less than three times EBITDA for many sectors.

Fixed charge cover

Also worthy of note is whether there are preference shareholders that have to be paid or other providers of debt to the company such as convertible bonds. The payments to these people effectively constitute interest or a fixed charge, where the providers of this money have a priority claim on funds before the shareholder. Some of these payments may occur ‘below the line’, i.e. after the profits figure has been struck. As a result, they may not feature in the interest line. Accordingly, they should be added to the interest payments when calculating cover. Sometimes this is referred to as a fixed charge cover ratio. Some people take into account other fixed charges, such as lease payments, as this is in effect a form of interest on an asset used in the business.

Credit ratings

A credit rating is a measure of the issuer’s ability to service and repay its debt. This will depend on:

- its financial position (the amount of debt, the liquidity position and other liabilities such as pensions and healthcare liabilities); and

- the performance of the business which after all is generating the cash flow to service the debt and ultimately redeem it.

These ratings are provided by the major credit ratings agencies such as Standard and Poor’s (S&P), Moody’s and Fitch. Table 5.1 highlights the range of ratings from S&P.

Table 7.1 S&P ratings

A company with very sound finances – very little debt and strong and predictable cash flow – will have an AAA rating. This means it can raise money much more easily and cheaply. Anything above BBB is regarded as ‘investment grade’. When a company is below BBB it is not investment grade (rather it’s ‘junk’) and then the costs of raising money increase dramatically as the risk of the company defaulting on its payments is so much greater.

The ‘cult of debt’ experienced in the past decade has seen the number of AAA-rated companies decline dramatically. The share buy-backs, leveraged buy-outs and debt-fuelled mergers and acquisitions of this period have inevitably seen credit ratings come under pressure.

Strikingly, the number of companies rated A and higher has tumbled to just 11 per cent, from 17 per cent in 1998 and from 50 per cent in 1980. In the US only five AAA-rated stocks are left: Automatic Data Processing, Exxon Mobil, Johnson & Johnson, Microsoft and Pfizer. Therefore, given the much higher proportion of debt below BBB grade, the risk of companies defaulting in the current environment is so much greater, especially given the weak economic outlook.

Over time the proportion of US industrial companies (excluding utilities and financial institutions) in the B rating category account for nearly half of all S&P’s corporate credit ratings whereas this category made up just 7 per cent of ratings in 1980.

According to S&P, 75 entities worldwide, representing debt topping $174 billion, were identified as potential fallen angels in January 2009. This compares with an average of 47 potential fallen angels per month in 2008.

A number of concerns have been voiced about the independence of the credit ratings agencies as a result of the credit crunch and the poor performance of many instruments that had been assigned AAA ratings. Crucially there has also been an issue that a downgrade of a company’s debt comes far too late. This makes the debt rating a lagging indicator whereas the shares are likely to be an effective way of anticipating the troubles ahead.

Covenants

There has been much concern about highly indebted companies breaching their banking covenants. This reflects the fact that their financial positions have deteriorated and some key ratios such as interest cover (operating profit/interest payable) that will have been stipulated in the covenant have fallen below prescribed levels.

We saw in the operational gearing example that if prices for the companies fall 5 per cent then profit could halve. Clearly then interest cover would halve. In that example interest cover fell 2∞. This represents a level at which the providers of debt will be getting very nervous, especially if the prospects for the company’s revenues remain uncertain. It would probably be in breach of its covenants.

Not only will a covenant stipulate the level of interest cover required, it will stipulate the method of calculation. Otherwise companies could use favourable interpretations of accounting policies to try to keep the numbers on the right side of the line.

Breaching the covenants means that the debt providers can demand immediate repayment. However, in most instances discussions will take place to renegotiate the terms of the debt and if this is agreed then the company will be paying much higher interest costs as a result. Obviously, in a worst case scenario the company will default on its debt and go bankrupt. (The banks may then go for a debt–equity swap if that is deemed worthwhile.) These discussions may see the company agreeing to sell off assets – this may be good for the banks but less attractive for equity holders if they are key assets of the company and are sold at distressed prices. In other situations the debt may be rolled over only if equity holders inject additional funds.

Why high gearing may hurt the company and its share price

Generally speaking, a higher level of gearing suggests a higher level of risk. Below we detail some of the problems associated with high gearing and the adverse impact it may have on a company and its share price performance.

- Higher risk. An important aspect of the higher debt levels is that the risks are greater. This will put off potential investors who might have been interested in the situation if debt was at lower levels (i.e. they have low risk thresholds and may invest only in companies with low gearing). Clearly if interest rates are expected to rise, investors will be wary of getting involved.

- Cash flow servicing debt – cannot invest. This will undermine the valuation of the shares, especially when combined with the risk of a rights issue. A company with a high level of gearing may find that it cannot fund investment in maintaining the quality of assets or the growth of the business. This could be very dangerous competitively. Good commercial opportunities may be missed as the company takes too long to raise the money or cannot raise it all. This will undermine the valuation of the shares, especially when combined with the risk of a rights issue.

- Business run for creditors not for shareholders. One of the central problems if gearing is at very high levels is that the management will be taking decisions favoured by the bankers, which may well not be in the long-term interests of shareholders. Discretionary costs such as marketing and R&D are likely to be reduced and capital expenditure cut back. In addition, promising projects may have to be abandoned. Creditors anxious to get their money back may also force the company into selling off its most valuable assets. As a result shareholders may not be invested in what had attracted them to the company in the first place.

- Risk of rights issue. The higher the level of gearing and the weaker the cash flow, the much greater the risk of a company having a rights issue. This may be avoided by selling off assets, although that involves the risk that the most saleable assets are the most profitable. A rights issue in itself may not be a major depressant on a share price, but the laws of supply and demand suggest a lower share price.

- Cost of debt. Another problem for a company with high debt levels is that the cost of borrowing will tend to rise to reflect the higher risk of default. Bond issues by telecoms companies following their heavy investment in expansion in the late 1990s saw the cost of servicing their debt rise sharply as lenders, concerned about their poor financial position, demanded higher rates. This problem is compounded if much of the existing debt is at variable rates and interest rates are generally rising.

- Obviously, if there are substantial amounts of debt, if the cost of that debt rises by 3 or 4 percentage points this will have a big impact on debt costs and hence reduce profits significantly. When this works through to earnings, the dividend is likely to be cut (especially as the trading environment is also likely to be difficult in these circumstances).

- The credit ratings agencies have had a significant impact on this concern. Indeed, the ICI rights issue in 2001 was very much driven by debt ratings agencies warning of what would happen to the cost of debt if action was not taken to reduce debt and of course in the current environment many rights issues are taking place for the same reason. This led to a deeply discounted and underwritten rights issue. The downgrading of companies’ credit ratings can have a severe impact on share prices and again highlights the risks involved for shareholders.

- Low dividend growth. The need to service high debt levels will mean that the ability to grow the dividend is limited. This may be a deterrent for those investors that have a requirement for a growing income. This, combined with the inability to invest in the business, leaves the shares looking very unattractive.

- Bankruptcy. If the financial position deteriorates dramatically, ultimately a company may be forced into bankruptcy. If the business prospects are poor and it cannot service its existing debt, it will prove impossible to continue to fund the business on an ongoing basis. The fate of Marconi is salutary here – while it has not gone bankrupt, shareholders have ended up with a mere 0.5 per cent or so of the equity, as bondholders converted their bonds into shares.

How much debt should the company have? Efficient balance sheets

The increasing use of ‘economic value added (EVA)’ approaches to investment analysis in the 1990s led to a lot of attention being focused on ‘balance sheet efficiency’. This means that by having the right level of debt and equity you will minimise the cost of capital. Indeed a very large investor based in the UK, Hermes, has as one of its principles for companies the following:

Lowering the cost of capital

Principle 6 ‘Companies should have an effecient capital structure which will minimise the long-term cost of capital.’

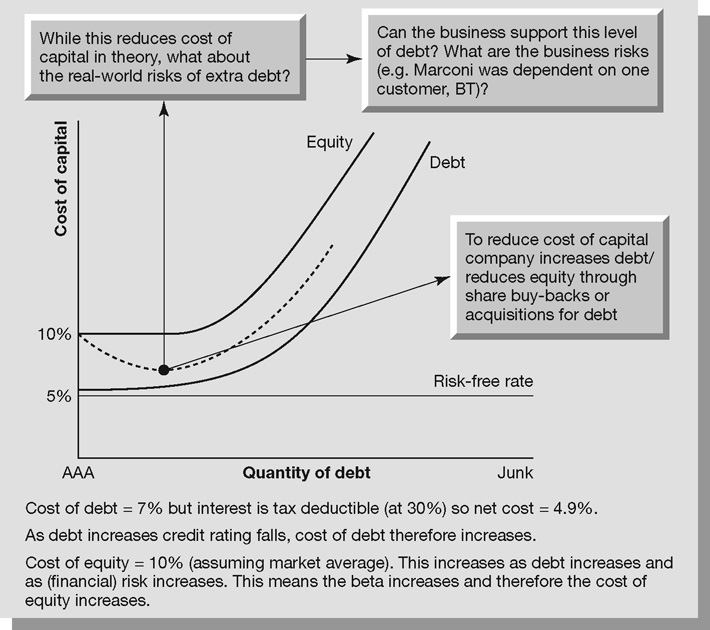

Gearing and returns

The notion of efficient balance sheets highlights that gearing can be a good thing – as demonstrated by Figure 5.3. It is much cheaper and more tax efficient to fund businesses with debt (the debt payments are deducted before arriving at pre-tax profits). This improves returns. In many cases it is similar to the advantage of buying a property with a mortgage accounting for 100 per cent of the value of the property. Any increase in the value of the property then belongs entirely to the mortgage holder.

It can also be the case that the debt ensures that the business is run efficiently. There is the discipline of making sure the debt can be serviced and that there is extra left over for shareholders.

High gearing and volatile income to be avoided

A high level of financial gearing, however, combined with a high level of operational gearing can be extremely damaging in a downturn. If volume and/or prices fall in a business with high fixed costs, operating profits and cash flow will fall dramatically. This might make it very difficult to service the company’s debt and may well lead to the dividend being cut. In a prolonged downturn this may lead to a period of poor performance and conceivably bankruptcy.

Adding value is defined as producing rates of return over and above the cost of capital. Companies with low levels of debt were encouraged to engage in share buy-backs to improve their cost of capital by increasing the proportion of (cheaper) debt in their financing mix. Gearing generally in the corporate sector has been on a rising trend, partially due to this drive for balance sheet efficiency.

Figure 5.3 Figure 5.3 Efficient balance sheets

It is also worth bearing in mind that (debt) capital was not only cheap in the 1990s and early 2000s, it was widely available. Therefore there was a strong climate that encouraged share buy-backs and of course the private equity industry was very busy taking companies off the stock market and loading them with debt. Indeed, what would happen was that a company that was bid for by private equity would use share buy-backs as part of its bid defence as this was seen as being shareholder friendly.

The current environment is far less supportive of share buy-backs but that does not mean to say that they should not be considered: it does mean that the case for buy-backs has to be rigorously applied and the reasons behind them confirmed as ones that will create shareholder value.

So companies with very strong balance sheets – stable low-risk businesses which require little new investment – may well have a case for a buy-back. In the oil sector, for example, Exxon has been judiciously using buy-backs.

Therefore having an efficient balance sheet means having the right level of debt to minimise the cost of capital. (It should be borne in mind that this only works if the conditions cited above – stable revenues, strong cash flow, low operational gearing, etc. – are all in place.)

So a company that has cash on its balance sheet or no debt would be deemed to have an ‘inefficient balance sheet’. To make the balance sheet efficient it needs to increase the amount of debt (reduce the amount of cash) and it can do this by:

- investing in the business

- making acquisitions for cash

- a share buy-back

- a special dividend

- increasing ordinary dividends.

However, before engaging in any of these activities it is worth considering the following questions.

What type of business is it and how competitive is it?

A key issue is whether the business is capable of having higher gearing – what type of business are we talking about? The advantages of gearing up in terms of reducing the cost of capital and the disciplines of higher debt are confined to companies with predictable revenues (especially price stability) and cash generation. A high proportion of fixed costs (high operational gearing) is also a significant deterrent to debt. Combining high operational gearing and high debt levels is very dangerous – relatively small movements in revenues significantly impair the company’s ability to service debt.

The retail, property and hotels sector saw significant buy-out activity during the boom of 2004–07. The asset backing provides a major opportunity to secure lending – banks will often lend up to 90 per cent against property as opposed to around 70 per cent for an operating business. In some deals this has seen the operating company split off from the property assets. The ongoing rental liability services the debt secured on the property assets. However, given the severity of the downturn many retailers, property companies and hotel companies have run into serious financial trouble.

Questions inevitably arise as to whether operating businesses in these sectors have the degree of visibility of revenue and cash flows to service the high rents and/or high interest payments involved in higher debt levels. This reinforces the notion that it is the visibility of the revenue streams and cash flow that is crucial when gearing up, not the asset backing.

If the company has a high debt burden and a significant amount of cash flow is servicing debt, there has to be a major concern that the company’s competitive position, due to underinvestment in the business or its brands, is severely undermined. These concerns have been manifest with buy-outs returning to the equity market. Given the high leverage and the implications this has for investment in the business, investors were, not surprisingly, very wary about buying these assets back from private equity and very circumspect about the price they would pay. There were concerns, for example, at Premier Foods that the brands had been starved of advertising, which in a very competitive marketplace may result in an erosion of long-term market share. Clearly such a fall in market share severely affects the company’s long-term ability to service debt.

Therefore, while the financial structure of a company is a key determinant of its cost of capital, in the long run it is the company’s competitive position that will determine its ability to add value and service its liabilities. This requires a clear strategy and the managerial and financial resources to compete effectively. While there are advantages to debt finance, it can be self-defeating where competitive pressures need to be met with significant investment.

How will the cash be returned?

If the balance sheet is inefficient and the business can support higher debt without incurring extra risk or undermining the competitive position of the business, the main debate centres around the most effective way of returning the money to shareholders: via a buy-back, a dividend increase or a special dividend. Each has merits in different contexts. As well as the impact on the cost of capital, the other main issue is what each action ‘signals’ to investors.

The tax implications for shareholders will differ and also need to be taken into account. Typically capital gains are taxed at a lower rate or have scope to be managed in a way that income cannot. Buy-back programmes often have structures such as ‘A’ and ‘B’ shares which enable investors to defer crystallising a capital gain.

Another important factor in determining how to remedy the inefficient balance sheet are the different objectives of shareholders – a register that contains mainly ‘value’ shareholders may have very different views from a register mainly populated by ‘growth’ investors. In the current market ‘growth’ appears to be returning to favour – these growth investors on the register may prefer the company to engage in M&As or significant capex programmes.

What is the cost of capital?

A share buy-back corrects an inefficient balance sheet – that is where the company has too much cash (or too little debt) on its balance sheet given the business it is in, the cash it generates and its need for capital for investment. Having more debt on the balance sheet will reduce the cost of capital as debt is both cheaper than equity and enjoys the advantage of being tax deductible. (This is sometimes referred to as the ‘tax shield’.)

By substituting cheap debt for expensive equity the cost of capital is reduced thereby creating value for shareholders. One of the main advantages of a buy-back is that by reducing the cost of capital, future cash flows are discounted back at the lower rate. This can produce significant changes in the value of the business which is then spread over fewer shares in issue.

Are the shares ‘cheap’?

The traditional reasoning favouring a buy-back is that management is demonstrating it believes the shares are significantly undervalued given the company’s excellent prospects. The management is buying an asset it knows. Importantly, the share buy-back is not a cash return to shareholders – it is an investment in the company and shareholders can choose whether to take cash by selling their shares or not.

As the buy-back is a capital allocation decision/investment, it needs to be done at an attractive share price. As Warren Buffett argues, it hardly makes sense to pay $1.10 for a $1 bill. Investors retaining their shares will own a greater proportion of the company and have a greater stake in its future. As a capital allocation decision, share buy-backs only make sense if the shares are cheap. This does of course raise a key issue: does management have the ability to identify whether the shares are cheap or ‘fairly valued’?

If the shares are ‘intrinsically’ cheap (see p. 192) then management by engaging in the buy-back is ‘signalling’ to the market that it believes the company to be undervalued on a long-term basis and that there is no better home for the surplus capital than its own shares. Many shareholders (including Warren Buffett) do look at it this way – and for good reason.

Clearly if the shares are ‘up with events’ or expensive then a buy-back may not be appropriate. A company buying your shares at an overinflated level will destroy value. In which case a ‘special dividend’ or an increase in the ordinary dividend is far more appropriate.

It is not about earnings per share – is it?

Often companies who should know better will refer to the benefit of the share buy-back as having a positive impact on EPS. This is not the rationale for the share buy-back. Any impact from a rising EPS is offset by the higher risk of financial gearing which will reduce the P/E. Crucially, given the change between the equity and debt components of the company’s funding, it is far more appropriate to consider enterprise value when assessing the company’s value (see p. 273). This obviously in theory remains the same (the business is just funded differently): the EV/sales ratio (say) would stay the same and this should only improve if the company’s operating margins or sales growth improve. As we stress below, improving the strategic and operational performance of the business is a crucial element in successful buy-backs.

On a corporate governance note, here it might be that the buy-back is helping the company meet earnings target which also happen to be the key trigger for the executives’ remuneration packages. Again having a target like earnings – which does not necessarily reflect the performance of the business or the creation of economic value – does not make a lot of sense.

What about capital allocation and returns?

In many instances the main reason for the share buy-back may be to reduce the cost of capital and thereby increase shareholder value. However, it may also be desirable from a shareholders’ perspective to ensure that a company with a poor track record in doing deals – acquisitions that consistently fail to add value – does a share buy-back rather than engage in further value-destructive deals. In effect, shareholders are saying that ‘we do not trust you to add value when doing deals’.

This does, of course, beg the question as to why shareholders should trust the management to run the existing assets in the first place – which of course may actually trigger a change in the management team, especially if they are not responsive to shareholder demands.

It is crucial to use shareholder value in evaluating M&As so you should also consider them when doing buy-backs: buy-backs are clearly a form of capital allocation in the same way capex or M&A is. The buy-back must ‘signal’ a commitment to shareholder value when deploying shareholders’ money.

What about capital discipline?

Shareholders are effectively putting an important capital discipline on management. This discipline comes about as (arguably) greater gearing concentrates the mind and makes management far more focused in generating cash returns to service the debt. In addition, as there is little capacity for extra debt, management has to be very selective in capital allocation decisions. In theory, therefore, this rationing ensures management will only engage in projects that generate the best returns. (The ultimate gearing discipline is of course being taken over by a private equity firm where the firm is substantially backed by debt. Thinking of share buy-backs and private equity as part of a continuous spectrum is a useful way of thinking about company funding. Clearly the private equity approach pushes the efficient balance sheet/cost of capital argument to its limit.)

Will there be an increase in the ordinary dividend?

Interestingly, anecdotal evidence seems to suggest that for some very large companies, buy-backs do not seem to have much impact on the share price. This may reflect the fact that the company is of a size where it is indeed ex-growth and the buy-back merely confirms that.

However, what may be more important is that the share price effect is probably reflecting a cross-over point between growth and value investors which will take time to correct. (Growth investors are selling the shares as they no longer offer the prospect of above average growth. However, the yield on the shares has not risen to a level – i.e. the share price has not fallen far enough – to entice value investors.) This is not for one moment to say that the company is all of a sudden a ‘bad’ company, only that its investment appeal has changed significantly as it moves beyond a certain point in its life-cycle. The enhanced ordinary dividend ‘signals’ the board’s confidence in its long-term cash generation capabilities. It also suggests that maybe income rather than capital gain will be the key component of total shareholder return (TSR).

In this situation some might argue that a sharp increase in the ordinary dividend is therefore a better ‘signal’. This is because it commits the company to an increased payout ratio in the future. This ‘permanent’ payout will impose greater discipline on management. If the company is offering lower growth (but is highly cash generative) this makes perfect sense. All the statistical evidence suggests that it is in fact growth in dividend – not a high starting point – that makes money for investors over time. One could argue that Vodafone moved from being a growth stock to a utility. Accordingly, its yield needs to reflect this – and increasing the ordinary dividend and payout ratio would help this process.

Value shareholders (who put more emphasis on the certainty of income rather than the uncertainty of capital growth when assessing total shareholder return) would then find the shares more attractive. Inevitably, however, in some situations management teams are invariably reluctant to acknowledge such a dramatic change in the status of the company.

What are special dividends?

Given that share buy-backs work most effectively if the shares are below their intrinsic value, returning cash to shareholders if the shares have had a strong run or are ‘fairly valued’ by the market poses a different problem. If the shares are fairly valued and management does not feel it appropriate to commit itself to a permanent increase in dividend levels, a ‘special dividend’ may be the most effective way of dealing with surplus cash.

Often special dividends accompany a disposal or a ‘one-off’ gain for the company. (As it is a one-off gain an increase in the ordinary dividend is not appropriate.) A good example is Carillion which has declared that it will pay a special dividend whenever it makes a disposal from its portfolio of private finance initiative investments. As these are one-off events and may occur infrequently a special dividend is an effective way of dealing with the cash proceeds of the disposal.

Clearly if the shares have had a very strong run – perhaps anticipating a major disposal – then this tilts the argument in favour of a special dividend instead of a buy-back.

What about company performance and strategy?

Rather than just focusing on the ‘financial engineering’ of share buy-backs, real value is driven by making the core business more efficient and competitive. A clear and credible strategy that will deliver improved competitive performance, cash flow and earnings is absolutely critical – the benefits of this are then magnified for long-term shareholders with the improved performance being spread over fewer shares. Similarly this suggests that there may be a case for higher investment in a business or small bolt-on acquisitions rather than returning funds to shareholders. This obviously assumes you trust management to deliver value from such initiatives!

A disposal of a non-core business accompanied by a share buy-back may be greeted positively as it means management can focus on the core business and generate better returns from it, and these improved results will be spread over fewer shares. The cost of capital is reduced but management time is freed up to improve the performance of the core business which will now be valued more appropriately rather than being dragged back by the underperforming non-core operations. Future improvements in performance will then see share price growth.

In this situation, take a shareholder with a 10 per cent stake. A non-core division is disposed of, realising 25 per cent of the market cap. If the shares are bought back then there are now (say) 25 per cent fewer shares in issue. If the shareholder believes that the management is now focused on generating value for them and is making the right decisions about the core that will create a more competitive position for the business, they will hold on to their 10 per cent. (This presupposes that management has done an excellent job convincing investors it can effect a turnaround.)

If the performance of the business improves significantly the shareholder now has 10/75 or 13.3 per cent of the equity. This can be viewed as the opposite of the dilution you get with a rights issue. Therefore this shareholder is entitled to 13.3 per cent of the enhanced EPS and cash generation of the improving business. As mentioned above, the DCF calculation will also make the business more valuable as the discount rate will be lower reflecting the lower cost of capital – not only is the debt higher but the increased focus on the core business should also reduce risks.

Too many management teams just focus on the buy-back. For many large companies engaging in a share buy-back the share price response will be very disappointing if it is not accompanied by actions to improve the underlying performance and/or growth of the business. Clearly, for very large companies this may be a ‘Catch 22’ as they are handing the money back because they do not have major value-creating growth opportunities open to them. (Maybe in this case they should consider the ordinary dividend route discussed above?) Nonetheless, a clear strategy needs to be explained to the market regarding what returns are likely to be delivered in the future.

When do share buy-backs work?

Share buy-backs therefore make sense for a company when:

- the business profile – visibility of cash flows – means it can cope easily with the higher levels of debt

- it has an ‘inefficient’ capital structure – that is, the company does not minimise the cost of capital because it has lots of cash or very little debt on the balance sheet

- the company does not require lots of investment to ensure it remains competitive or is missing out on growth opportunities – investments that, if made, will generate shareholder value

- the company’s share price is undervalued

- it creates value.

Critically, all of these conditions need to apply if the buy-back is to make sense – overpaying is hardly in shareholders’ interests, while incurring extra risk of higher debt finance when it is not appropriate is hardly sensible.

Buy-backs must not be seen as an isolated, short-term response to a flagging share price but as part of a committed, long-term approach to shareholder value. Management must have a clear and credible strategy for delivering improved returns, earnings and cash flow, which spread over fewer shares will benefit those long-term shareholders that have supported the management and its strategy.

There is still a negative association regarding share buy-backs. The situation is often interpreted as indicating a company that is ex-growth with few value-added opportunities for investment or lacking strategic direction. This is particularly important in high-growth sectors where investors are expecting the company to exploit growth opportunities. (Interestingly, buy-backs in the high-tech area are often to avoid the dilution that accompanies employee share option schemes.)

However, buy-backs should be appraised in terms of value creation not growth. Many capital allocation decisions grow earnings but destroy value. Similarly, buy-backs do not excuse a company from having a credible strategy.

Therefore, while the financial structure of a company is a key determinant of its cost of capital, in the long run it is the company’s competitive position that will determine its ability to add value. This means that it can generate the profits and cash flows to service its liabilities. Higher levels of debt – especially if competitors are more conservatively financed – may well undermine the ability to compete. Being competitive requires a clear strategy and the managerial and financial resources to position the company effectively. While there are considerable advantages to debt finance, it can be self-defeating where competitive pressures need to be met with significant investment.

During the boom years of 2003–07 debt was fashionable and available – the ‘cult of equity’ was very much replaced by the ‘cult of debt’. This helped facilitate the move to higher gearing and encouraged companies to use debt finance.

However, the impact of the recession, the ‘credit crunch’ and the widespread use of debt by companies without the quality of earnings/visibility of revenues to service that debt has inevitably led to companies needing to refinance through the equity market.

The fashion has swung back towards low gearing and ensuring a sensible debt profile – i.e. a long-term structure of debt. This has seen many companies – some with more choice than others – engaging in rights issues.

Raising fresh capital: rights issues

The ‘credit crunch’ has seen access to bank loans and in some instances the bond markets closed off as a source of finance for many companies. Given the severity of the recession and the impact on profits banking covenants have either been breached or close to breaking. This has put many companies in a very serious financial position.

For companies with lots of debt that sell goods to consumers who are both in debt and need to raise debt to purchase the product (selling ‘high-ticket’ items), the challenging trading conditions may persist for some time. The process of ‘de-leveraging’ (cutting debt levels) may take a considerable period to work through for both the corporate and consumer sectors.

So with access to debt so difficult companies need to raise finance from their shareholders to ensure their survival – although of course companies in healthier positions can raise capital to fund growth plans too. In extreme cases, if the company is in trouble the debt of the business may be converted into shares if the company cannot survive any other way. In this situation the original shareholders may be left with nothing, paying the ultimate price for the risks of investing in shares as shareholders come bottom of the pecking order.

A ‘rights issue’ is a way in which a company can sell new shares in order to raise capital. Shares are offered to existing shareholders in proportion to their current shareholding, respecting their pre-emption rights. Pre-emption rights simply means that as an existing shareholder of the company your are entitled to have first say as to whether you want to support the fund raising and preserve your share of the business. It would obviously be very unfair if the company found a fantastic investment opportunity and to fund it decided to give shares to a new shareholder who had not supported the company in the past. Given that equity means fairness this would be a completely inappropriate way to act. For example, there was has controversy over the way in which Barclays raised money from sovereign wealth funds in the Middle East at very attractive rates for the investors.

There has been some suggestion that both the rights issue process and the role of pre-emption disadvantage certain companies. So, for example, small technology and bio-tech companies may have greater flexibility raising money through a series of placings where a smaller amount of shares is ‘placed’ with investors prepared to back the fund raising. In terms of the process the very heavy rights issues by the UK banking sector arguably caused many problems. The length of time it takes to raise the money meant that hedge funds could effectively sell the shares ‘short’.

With the pre-emption principle being maintained shares are offered in proportion to an existing holding. So, for example, there may be one share issued for every two shares held. This is referred to as a one-for-two. Clearly the more money that needs to be raised the more shares will need to be issued.

The price at which the shares are offered is usually at a discount to the current share price, which gives investors an incentive to buy the new shares – if they do not, the value of their holding is diluted (they will be holding a lower proportion of the company than before the rights issue). The extent of the discount will depend on stock market conditions and the ‘heaviness’ of the rights issue (i.e. how much is being raised and does that mean we are looking at a one-for-one rather than a one-for-five issue). In recent times many companies have engaged in ‘deep discount’ rights issues where the shares may be at a 50 per cent discount (say) to the previous share price. This is done to ensure the shares are attractive and so raise money. In the past this was also often done so that the company could avoid having to underwrite (or insure) the rights issue to ensure it got the money. However, given market conditions even deeply discounted issues are being underwritten.

Example – how rights issues work

Company A needs to raise £150 million. It has a share price of £2.00 (the pre-rights price) and there are 200 million shares in issue. Its current market capitalisation (shares in issue ∞ share price) is therefore £400 million. The company is going to do a deeply discounted rights issue at £1.00.

It therefore needs to issue 150 million shares at a £1.00. There are 200 million shares in issue so by having a rights issue of three new shares for every four shares held there will be 150 million new shares created. The rights issue is therefore three-for-four at £1.00.

You as a shareholder can then buy three shares at £1.00. Given that you hold four shares at £2.00 you would then have £8.00 worth of old shares and £3.00 worth of new, or £11.00 invested in seven shares. Each share is then worth £11.00/7 or £1.57. This is known as the ‘theoretical ex-rights price’ or TERP.

The new shares are being sold at a 50 per cent discount to the pre-rights price or a 36 per cent discount to the TERP.

Technically the money is regarded as being raised at the current market price and there is then a bonus element to the rights issue and so previous year’s earnings per share are adjusted by the TERP divided by the last day of dealing cum-rights price (i.e. the shares are still entitled to take part in the rights issue). If this stayed at £2.00 then the adjustment factor would be 1.57/2.00 which is 0.785. More realistically the shares may drift off towards the TERP. Alternatively, we know that there are now 350 million shares in issue and 75 million shares would be issued at £2.00. This means that the scrip element is 75 million/350 million or 0.214. So the previous year’s earnings would be 21.5 per cent less than previously stated.

For investors there may be a significantly greater reliance on rights issues in the future so knowing the options and impact of them is clearly very important.

Example – options for investors

Following on from the above example, let’s say you have 1000 shares. Originally worth £2000 these are now worth £1570 at the TERP. There are three options:

- Take up rights – If you accept the issue in full then you will be investing in 750 new shares at £1.00 or £750.00. You then have 1750 shares at 1.57 or £2747.50 in total and have the same proportion of the company as you did before so you have not been ‘diluted’.

- Sell enough to be cash neutral – If you cannot afford this you could sell enough rights to take up the remaining rights: you can sell rights at 57p if the shares fall to the TERP. The rights are therefore worth £427.50 (which almost takes you back to the value of your original investment). So by selling half the rights this would generate £213.75, enough to buy 214 shares when rounding. You now hold 1214 shares.

- Let the rights lapse – If you do not subscribe for your shares the company will sell your rights at the market price on your behalf.

Do you hand your money over?

As ever, when a company and its management team are asking for money the key issue is whether we trust that management team to use the funds to make a real difference to the business and make money. So you need to ask yourself:

- Why are they raising the money?

- What will they do with it?

- Will this generate an appropriate return?

Of course it is complicated with some rights issues because there may be very dire consequences if we do not support the company. However, if we do not have faith in the management team then a change of management may be a condition of the money being raised. Here larger investors will have to play a role to effect the changes needed.

Work done by Morgan Stanley suggests that rights issues are most successful – that is, the shares go on to perform well – when

- the shares have been very poor performers

- the company raises a significant sum relative to its market capitalisation

- the funds raised are used to reduce debt.