2

Sector and market background

What topics are covered in this chapter?

- Why look at the sector first?

- What drives sector profits?

- What is the outlook for demand?

- What is the outlook for prices?

- What is the outlook for costs?

- General economic and stock market factors – how do they affect the sector?

- Summary

- Checklist

Why look at the sector first?

It is worth looking at the sector first as it gives you a quick sense of how difficult or otherwise it is for a company to make money. Historically, if the sector has found it difficult to make money and generate good returns, we must explore the reasons for this. This immediately may save you time as you can eliminate the sector as one where it is difficult to make money or, importantly, where the risks for you are too high.

What are the economic characteristics of the sector? What attributes does a company need to succeed in such an environment? Overcoming the difficult economics of an industry can be done, but it needs a special company with special characteristics to achieve this and it is quite rare. The sector may be prone to price wars, it may be cyclical or it may have a record of investing in huge amounts of capacity just as the economy turns down.

If you have found a stock that you find interesting in a sector that has historically failed to make money, you need to have a particularly good case for investing: what is different about the company that will enable it to succeed?

A number of sectors have historically failed to make money for shareholders over long periods. Steel, chemicals, paper and packaging, automotive and airlines spring to mind as areas that have been prone to losing investors’ money on a long-term basis. This may reflect a combination of interrelated industry characteristics that profoundly affect the ability of a sector to create wealth. For example:

- Overcapacity. This leads to poor pricing and severe competition for market share. In theory if it is making no return this capacity should be withdrawn. In reality it tends to be the case that there are ‘barriers to exit’. It may be expensive to withdraw or there is a temptation to wait for things to get better. When demand does pick up, there is too much capacity (and/or too many competitors) chasing the higher volumes. This leads to pressure on prices and will prevent a profit recovery.

- Highly capital intensive. The high fixed costs that are a feature of highly capital-intensive industries mean that there is a tendency for the companies in the industry to go for volume. Again this leads to pressure on prices. The high amount of capital employed combined with weak pricing will lead to very poor returns on that capital.

- Commodity products. An inability to differentiate between products means that competition is likely to focus on price. It may also mean that there are few barriers to entry. Prices are likely to fluctuate a great deal, with management having relatively little influence.

- No pricing power. This will be a feature of market structure and will be influenced by the factors outlined above. It may also occur where the consumer shops around and can bargain on price. The internet has made prices increasingly transparent and makes shopping around much easier.

- Internationally competitive markets. Again this intensifies competition.

- Cyclicality. Demand patterns which fluctuate widely mean that an industry goes through a series of good and very bad years. It can be difficult to generate long-term wealth in such conditions.

These factors are not mutually exclusive. Indeed they tend to be interrelated. What is crucial is that they all tend to undermine prices. Poor pricing and underperforming shares are a key relationship that will feature throughout the book.

To illustrate some of these issues we will look briefly at two sectors where the historic performance has been poor – automotive and airlines. The points made are simple and general but describe some of the key factors accounting for the industries’ inability to make money. We will also look at the characteristics of a company that has managed to make money in each sector.

The automotive sector – factors driving poor returns

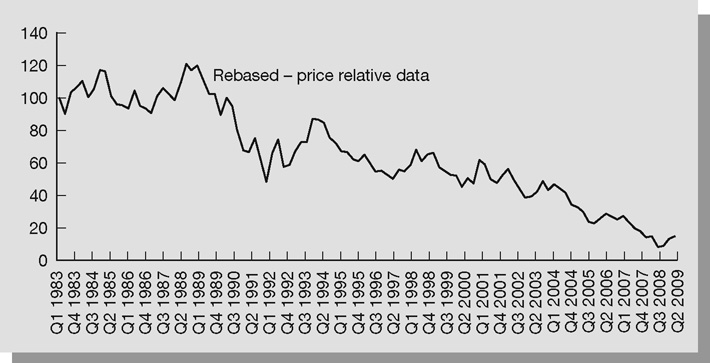

Figures 2.1 and 2.2 for the European and US automotive manufacturers illustrate a history of long-term underperformance relative to their respective local market. You would have lost a lot of money compared with just buying, say, an index fund that mirrored the overall market. The share price trend also shows great volatility, which suggests possible trading opportunities, although whether you have the skills to take advantage of that successfully is a different matter.

The automotive industry is a classic example of an internationally competitive market. Developing countries have encouraged indigenous car industries, often based on exports as an integral part of improving living standards. The industry has political importance in the developed world too – it is a large employer and the local company is often seen as a national symbol. State subsidies or loans have been important historically, helping to preserve capacity, as politically and economically it is expensive to close capacity in advanced economies while new capacity is being installed in developing countries. This new capacity will be more efficient than older facilities and labour costs are often substantially lower. It may be that the prospect for volume growth and perennial recovery hopes in the industry mean participants feel it is worthwhile to retain capacity. Closing capacity can also be an extremely expensive decision, which accounts for a reluctance to withdraw capacity.

Figure 2.1 The performance of the European automotive sector relative to the overall European stock market (Eurotop 300) since 1987

Source: Thomson Reuters DataStream

Figure 2.2 The performance of the US automotive sector relative to the US stock market since 1983

Source: Thomson Reuters DataStream

High costs are involved in building production plants and developing new products (these are sometimes referred to as ‘sunk’ costs). A high proportion of production costs are fixed. In addition, costs tend to rise as the cars produced have more and more sophisticated features while the real price of cars continues to fall.

These factors account for some of the difficulties with this sector. The industry tends to have permanent overcapacity, which leads to significant competition, domestic and international, which in turn serves to depress prices and margins. Volumes in the US automotive industry have been strong, but discounts to consumers and interest-free loans have cut margins to very low levels. Consumers are increasingly shopping around and, helped by the internet, are very price aware. This puts them in a position to negotiate keenly on prices. The weak pricing leads to weak margins which in turn put pressure on cash flow – a major problem for an industry with lots of capital to maintain, high costs and new product developments to undertake.

Therefore the combination of a high cost structure and a very competitive market makes for a difficult operating backdrop. This translates into poor pricing, high costs, low margins and poor returns on capital employed.

Porsche’s outperformance

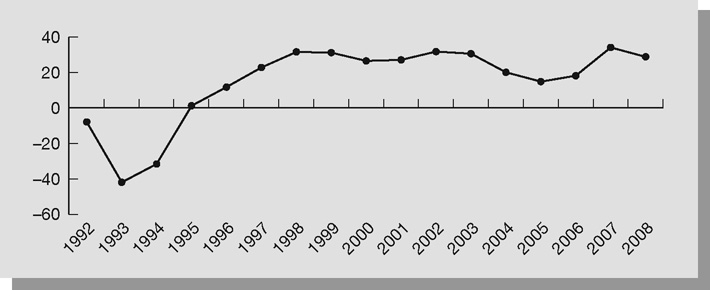

Given the issues surrounding the sector, Porsche’s outperformance of the European equity market is quite exceptional (see Figure 2.3). The trend in its return on capital is also impressive in the context of its industry (see Figure 2.4). Its qualities and strengths contrast interestingly with the sector problems identified above. Porsche has clearly defined itself as a luxury product and has not compromised this by going down market. This has preserved the value of the brand.

Having had difficulties in the mid-1980s the company radically restructured and reduced capacity. Rather than add capacity it has been happy to manufacture to order and has waiting lists for its output – this keeps capacity under control, keeps costs down and removes the risk of falling demand or producing so many cars that the exclusive cachet is lost.

Figure 2.3 Porsche’s share price performance relative to the European market

Source: Thomson Reuters DataStream

Figure 2.4 The trend in Porsche’s return on capital employed since 1992

Source: Thomson Reuters DataStream

Therefore, by keeping capacity well under control and operating in a distinct segment of the market where competitive pressures are much lower, the risk/reward ratio is much more in shareholders’ favour. However, maintaining exclusiveness of the brand is crucial in protecting sales and margins.

The airlines sector – factors driving performance

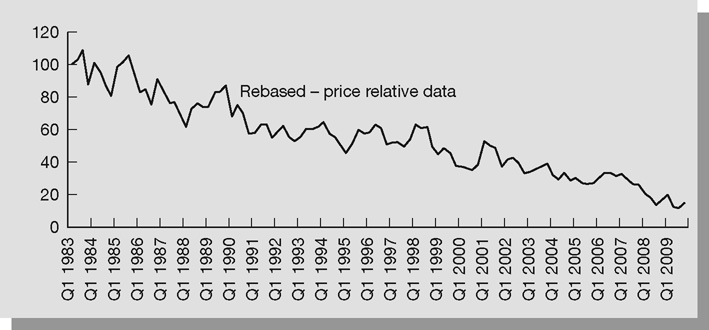

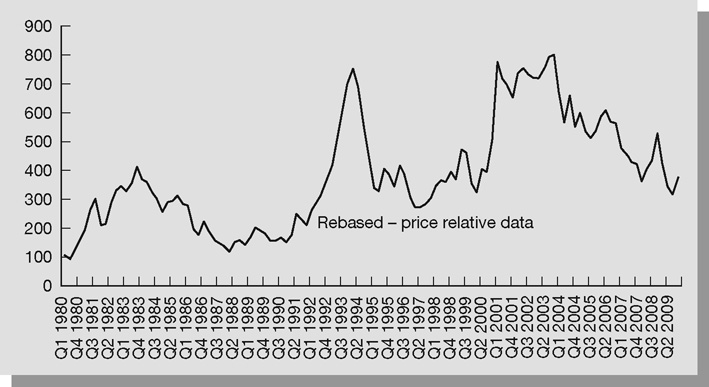

Figures 2.5 and 2.6 demonstrate that for both the world airline sector and the US sector there has been a clear, long-term relative underperformance against their relevant benchmarks. What is also a feature is the volatile pattern of these figures. Therefore the sector has lost money over time but has also been volatile. This may or may not suit your risk profile (an issue we will come back to frequently). If you feel that you have a thorough knowledge of the sector you may be able to trade it successfully. However, you need to be aware of the risks involved – you may want to have a short timescale or buy and sell on the basis of momentum (an investment style we will analyse later on p. 310).

The airline industry has also been affected by overcapacity issues. The combination of politics and the fact that an airline is a symbol of national pride makes for state subsidies and regulatory interference. As with the automotive industry, it tends to make it difficult for capacity to leave the industry. Costs are fixed in the sense that for each trip the same costs are incurred whether the aircraft is empty or full. Therefore small changes in passenger numbers can cause dramatic changes in profitability. Payments for landing slots and other fees to airport operators may also be unaffected by traffic. The cost of fuel oil is fixed and of course volatility in oil prices can cause major changes to sector profits. This might account for some of the sector’s volatility. Capital employed is very high, although sometimes the aircraft may be leased, not owned (if it is a finance lease this will make no difference).

Figure 2.5 The performance of the US airlines sector compared with the US stock market since 1983

Source: Thomson Reuters DataStream

Figure 2.6 The performance of the world airlines sector relative to the world stock market since 1983

Source: Thomson Reuters DataStream

Demand tends to be cyclical – affected by economic activity but also by global political stability. The cutbacks in company expenditure since 2000 have affected the travelling of high-margin business customers. Growth for low-cost operators has been strong, however. This highlights that barriers to entry have been circumvented by companies with a different business model. These operators and the transparency provided by the internet have put a downward pressure on prices and customers can make significant savings by shopping around.

Therefore, high capital intensity, high fixed costs, overcapacity and price pressure again combine to make the sector a poor home for long-term savings. These returns are disappointing given the risks involved.

Southwest Airlines – a star performer

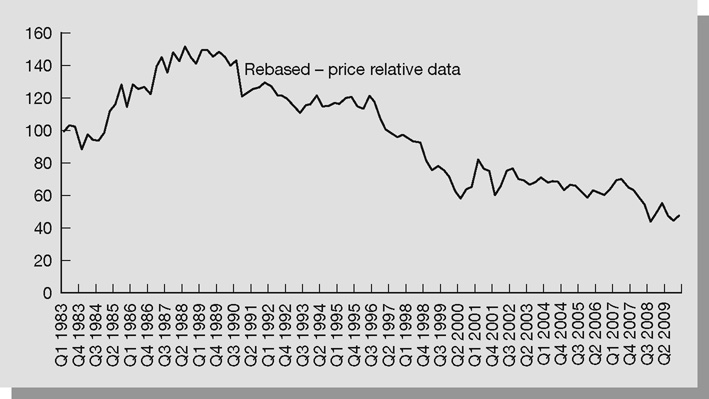

In a sector known for its highly cyclical nature and wide swings in returns, Southwest Airlines has been profitable in every year since 1973 despite having the lowest fares in the industry. It demonstrates an impressive earnings growth record and consistently high returns on invested capital and equity. While Figure 2.6 demonstrates a sorry tale, Southwest Airlines has been a star performer relative to the overall US market, let alone a very poor sector (see Figure 2.7). It has overcome all the industry difficulties cited above. Founded in 1971, it has provided the blueprint for other low-cost airlines that have emerged since the 1990s. The focus on costs is demonstrated by the fact that it has the lowest cost per available seat mile of any of the US airlines. This is achieved through ‘no-frill’ flights, only using 737s to economise on procurement and maintenance costs, avoiding the use of hub airports and maximising the fleet’s usage.

The airline has also been driven to provide high levels of customer service and customer satisfaction, and has an excellent safety record. Clearly, as Figure 2.7 demonstrates, it has found a simple and effective formula that works for both customers and shareholders. Sales and earnings have grown strongly since the 1970s and the company has delivered excellent returns on equity. These returns historically have been between 18 per cent and 20 per cent before falling to 13.7 per cent in the year post September 11th.

The success of Southwest Airlines highlights what is wrong with many aspects of the industry. The focus on low costs and customer service has clearly created a significant amount of value for shareholders. The company has also been deliberate in choosing which segments of the market and which routes it believes will make money.

Figure 2.7 The performance of Southwest Airlines compared with the US stock market since 1980

Source: Thomson Reuters DataStream

Top down or bottom up?

This process of examining the prospects and issues facing a sector is often referred to as a ‘top-down’ approach. Many investing styles will contest this on the grounds that we buy stocks, not sectors. But sector knowledge is a good starting point for providing a framework for understanding the key factors influencing the likely performance of a share. If, from the sector’s historic performance and economic characteristics, it is clear that it has rarely made money, you can save money and time by focusing on sectors with more compelling money-making characteristics. Alternatively, if there are certain trends and themes in the sector that appear attractive you will want to focus on those stocks that offer effective ways of playing these trends. Critically, you will be aware of the risks involved in investing in the sector. Porsche and Southwest Airlines clearly demonstrate that money can be made in sectors with a consistent tendency to lose money. However, the company must have special characteristics and a very different approach to the rest of the sector.

Once you understand what drives the sector you can then pursue a ‘bottom-up’ approach, focusing on the economics and strengths of a particular company. Chapter 4 deals with analysing the individual company.

What drives sector profits?

Having established that it is worth getting to grips with the sector context before drilling down to look at an individual company, the next step is to examine what drives profits in the sector. You need to ask:

- What is the outlook for demand?

- What is the outlook for prices?

- What is the outlook for costs?

What is the outlook for demand?

When considering the outlook for an industry or sector you must of course take into account the overall economic outlook. This will include the prospects for interest rates and consumer and business confidence, all of which will give you an idea of where in the economic cycle we are at present. You should also consider any predicted significant population trends, for example a baby boom or an ageing population, and any other social trends that are likely to change spending habits. Any research company or survey which provides well-thought-out predictions for the future will be widely reported in the financial press because it is exactly this sort of information all investors want in order to assess the prospects for one sector or company in comparison with another.

In assessing demand it is helpful to ask whether you are looking at a cyclical, mature or growth industry. This will immediately give you information about the outlook for demand regarding your target company. A cyclical industry is one that is known to have phases of doing well followed by lean periods; typically these follow the economic cycle or the interest rate cycle, which may be related. For example, the housebuilding industry tends to flourish during times of economic boom or low interest rates, but its investors and management expect it to do less well during a recession or when interest rates rise. This can mean that even if the economy is buoyant, if there is an expectation that interest rates will rise, housing shares may not perform as well as their business performance might warrant.

What drives demand?

If the sector is cyclical, it is important to isolate what drives the cycle. In essence this is trying to establish whether company, personal or government expenditure is what determines the overall level of demand.

The economic difficulties at the beginning of the 2000s are interesting in this context. The difficulties experienced by the corporate sector and its high level of indebtedness have seen companies cutting back severely on any discretionary expenditure. This affected a whole range of sectors supplying the corporate sector, whether it be advertising or capital equipment. Conversely, consumers were surprisingly resilient as they used debt and rising asset prices to fund consumption. As a result consumer cyclical stocks have had a relatively encouraging demand backdrop. Similarly, in the UK public expenditure was strong, favouring companies supplying public projects (or public/private ones if funded in that manner).

However, as we entered the ‘credit crunch’ environment debt became a problem across personal, corporate and government sectors. With the corporate sector heavily indebted and the banks having their own financing problems to resolve, expenditure pressures here may be present for some time. This is likely to affect airlines with exposure to high-margin business travel, hotels, capital goods and machinery, media (with their exposure to advertising) and IT and software – all of which are affected by company spending.

Another factor that will determine how cyclical demand might be is whether the product is a ‘high-ticket’ or ‘low-ticket’ item: this means whether the item is costly or inexpensive. A major piece of capital expenditure (capex) would be ‘high ticket’ and likely to be deferred or cancelled in more difficult circumstances – especially when raising funds is so difficult. For the consumer, a car or new kitchen might be deemed high ticket while going out for a pizza might be deemed low ticket. In difficult economic conditions one would expect high-ticket areas to be especially vulnerable.

Where in the cycle are we?

If you are considering investing in a cyclical industry, you need to know at which point in the cycle the industry currently stands. This will give a good guide to the outlook for demand. How can you tell? If the sector’s operating margins are very low and there have been several years of falling revenues, with prices depressed and poor demand, it is likely that the sector is close to the bottom of its cycle. Conversely, if margins are high and income (or revenue) is growing rapidly, it is likely that the industry is either at or approaching the top of its cycle.

Pinpointing the moment when the trend turns is by far the hardest part of the analysis for professional and small investors alike. Reading the cycle is not straightforward. In addition the sector may have ‘structural’ problems. These can include industry overcapacity, oversupply in the market, the impact of new entrants and problems among the customer base. All of these factors may mean that price, demand or profits do not recover when the economy or demand does and the share price continues to languish. The cyclical problems are prolonged.

The current situation is especially difficult, with debates about when and how sustainable any economic recovery will be given how much debt there is throughout the economy. This is compounded by the banks’ financial position, which makes it challenging for them to increase lending to an economy that is already over-geared and where defaults are on a rising trend. It may take some time for this debt to unwind – for the ‘de-leveraging’ process to take place – so the economy can resume more normal conditions.

A mature industry is one in which investors expect steady demand (for its products or services) at all phases of the economic cycle but where the capacity for strong growth in the overall market is unlikely. The industry is likely to grow in line with, or a little below, gross domestic product (GDP).

Examples of a mature industry in the UK would be food manufacturing or tobacco. Stable or gently growing profits over the whole of the economic cycle can be very useful, particularly during a recession. Mature industries are often good cash generators, which should mean a steady dividend. The strategic deployment of that cash flow will be a major issue at the stock-specific level.

A growth industry is one that is experiencing a significant increase in the demand for its products. The growth of the industry will considerably outstrip the growth of GDP. Often this is a young industry offering a new service or product, for example the mobile phone industry in the 1990s. It is also worth bearing in mind that in some instances growth sectors have turned out to be highly cyclical when the economy turns down. This has certainly been the recent experience of many technology stocks.

Growth industries are immediately attractive to the investor and will generate a lot of press and media comment. But a word of caution: high growth potential often attracts a lot of new companies which invest a lot of capital. This level of competition and high levels of capital investment make it difficult to generate the level of profits initially hoped for.

While the sectors have been broken down into cyclical, mature and growth components, a sector may have all these elements. The telecoms sector, for instance, tends to consist of mature fixed-line, conventional telephone operators as well as high-growth mobile operators.

What is the outlook for prices?

Prices are crucial to the investor. Falling prices are an effective method of destroying wealth. A price reduction comes straight off the ‘bottom line’, as revenues will fall sharply and so will profits as costs are relatively fixed. Take a company making operating profits of £10 million on turnover of £100 million. If prices fall 10 per cent, revenues will fall to £90 million – with costs unchanged, profit is eliminated. So an understanding of the key determinants of pricing in a sector is crucial.

We have already touched upon drivers of demand which are key elements in determining the outlook for prices. We now need to look at the other issues affecting the supply side and the competitive structure of the industry which influences price.

Porter’s five forces

A really useful model to understand the competitive position of a company sector is Porter’s five forces model (see Figure 2.8). Developed by Michael Porter in 1978 it provides an excellent framework for appreciating the competitive landscape and the pricing power of the company.

In the centre of the model we can see that competitive rivalry within the sector is a key determinant of pricing.

Competitive rivalry – industry or market structure

This is a major determinant of price. If an industry is fragmented, i.e. there are many small players, there is typically a lot of competition and prices are kept low. In Porter’s terms the intensity of competition is high. As an industry matures it tends to go through a period of ‘consolidation’. Companies merge with or buy each other, hoping to make it easier for them to keep prices higher and harder for new companies offering the same product or service to break into the market.

Figure 2.8 Porter’s five forces model

Source: Reprinted by permission of Harvard Business Review. From ‘How competitive forces shape strategy’ by Porter, M., March/April. Copyright © 1979 by the Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation, all rights reserved.

Consolidation does not always lead to higher prices. If the larger companies are determined to win an even larger share of the market, they may depress prices to win customers. The extreme example of this is a price war in which prices are cut now to enable a company to dominate the market in the future. The Times newspaper famously did this when it cut its cover price to 20 pence at the beginning of the 1990s. Waging a price war costs money and depresses prices across the sector. It is rarely good news for the investor, at least in the short term.

Competitive rivalry – market share aspirations and financial position

It is not just a consolidated market that is important – the participants need to be content with their market share as it is competition for market share that undermines prices. Therefore it depends on the aspirations and objectives of competitors. There may be a consolidated market, but if one of the competitors has a weak balance sheet and a need for cash, they may pursue a volume strategy to generate cash. This may or may not be sens-ible, but there is a danger it might happen.

Competitive rivalry – international competition

This is another important consideration. In general terms, barriers to foreign competition are coming down, encouraging new players into national markets, a process widely referred to as globalisation. This obviously undermines the market structure and will create a struggle for market share. International companies may have to target market share of the domestic market to make their presence worthwhile and to build a base for a longer-term push.

Some markets are already fairly international, for example car manufacturing, while others are still dominated by national players, for example high street (retail) banking. If foreign competitors are on the horizon it is likely they will depress prices.

Competitive rivalry – capacity position

Industries prone to large swings in demand are likely to see pressure on prices. The fluctuations in demand tend to be aggravated by the sector investing in new capacity at the peak of the market. The lags involved in bringing on stream new facilities invariably mean that demand has fallen by the time the new facility is ready. When demand does turn down, companies are keen to use this new capacity and tend to look for strong volume growth/market share. This inevitably depresses prices. It is perfectly understandable to look for volume – the new factories need to reach an efficient level of operation and this requires volume. In economic terms the ‘marginal cost’ of production is low so there is a temptation to go for volume as long as it makes a contribution to fixed costs.

This capacity concern can be applied to a whole range of sectors. Chemicals, airlines, insurance and paper are just some sectors that historically have seen capacity coming on stream to undermine pricing and hence sector performance.

Competitive rivalry – nature of the product or service

Clearly, a commodity product that cannot be differentiated will have less pricing power than a more sophisticated product (subject to the competitive conditions/market structure). A more sophisticated product has a greater array of features to compete on – the basis of competition is not just price but genuine performance benefits. Product differentiation should protect the company by building up brand loyalty and should provide a level of satisfaction that prevents consumers from switching to other suppliers.

Barriers to entry

If the structure of an industry changes, so will the outlook for prices. Investors must consider how likely it is that new entrants will appear that could significantly change the picture. Clearly the easier it is, the more fragile the profits of the existing players. There may be a technological development that means that a new competitor can establish an efficient, low-cost alternative to the existing players. The development of the technology to build ‘mini-mills’ in the US steel industry changed the economics of steel production. New players needed relatively small capital sums to enter the industry, compared with the established players which had huge amounts of capital committed. Similarly, the arrival of the internet has reduced entry costs for many businesses that may have previously required a widespread distribution network to service the client base. Amazon’s impact on book retailing is a case in point.

In general, barriers to entry will be determined by such factors as the following:

- Economies of scale – the greater the economies of scale, the more difficult it will be for a new entrant. They will need a very large amount of market share to make it worthwhile. Attempting to get this market share would lead to a price war, making the desired returns on investment difficult to achieve.

- Amount of capital – generally if vast sums of capital are required to enter an industry, new players will feel less inclined to take risks.

- Experience and steep learning curve – in some industries the skills and experience of the industry will deter new entrants. Customers may not want to buy a product or service from a new entrant if there is a lot of technical know-how involved. If the new player were to get it wrong, the customer would be massively inconvenienced.

- Presence of patents or licences – these make it extremely difficult for new entrants to copy the existing player(s).

- Distribution issues – the existing players may have such strong control over distribution channels that it would be very difficult to get a new product into the market.

- Product differentiation – genuine branding differences or performance characteristics will make it difficult for any new players to gain market share.

- Efficiency/low cost base – the more efficient and effective the industry is in serving its market, the less likely it will be that new entrants will feel there is an opportunity to take market share.

- Customer service – evidence suggests that when levels of customer satisfaction are very low, customers are more likely to try a new supplier.

An interesting and important example of where barriers to entry have been circumvented is the emergence of low-cost airlines. They have made a big impact on the industry and taken a significant degree of market share. If such airlines can lease the aircraft, then the barrier to entry – the capital limit – is avoided: that is, the company can rent the aircraft rather than having to find the substantial sums needed to purchase a very expensive piece of transport. There may have been a feeling that the industry’s cost structure was not sufficiently competitive, which meant there was scope to undercut the existing players. Similarly, the level of consumer satisfaction and the value for money equation provided by the existing players may have encouraged the low-cost airlines. If customers were very loyal to the existing players it would have made entering the industry much more challenging.

Threat of substitutes

Competing with a substitute product inevitably puts a limit on the pricing of the company’s products. This is especially true if there is a cheaper price but comparable product performance. This may be true for buying books second hand rather than new, for example, or it may be that many people see mobile telephones as a direct substitute for ‘fixed-line’ telephony. This will then limit the pricing power of fixed-line services as customers will migrate to mobile services.

This then raises the question as to how far the company can differentiate its product or services from the ‘substitute’ in a real sense. This must mean that the performance is somehow differentiated as being a lot better and the marketing creates a ‘brand’ that connects with people (see Buffett’s comments on Gillette on p. 62).

Bargaining power

Another useful question to consider is who has the bargaining power to determine prices in the industry. This will depend mainly on the relative sizes of the customer and the supplier. The food retail sector sees power rest with the distribution end of the system. Much has been said and written about the ability of the supermarkets to control prices. Companies supplying the food retailers will, in general, have little influence on pricing.

Another important example is the automotive industry. The size of the multinational car manufacturers means they place extremely large contracts which are very important for the supplier to win. These orders may also be placed on an international basis so that the supplier must meet that requirement to be able to fulfil the contract – a contract that will often stipulate that prices will fall on an annual basis over the contract’s life.

The price competition for the end product (witness the prices and dealer discounts, including 0 per cent finance offered in the US), however, means that operating margins for the car manufacturers are very low. Accordingly, there is significant pressure on them to reduce costs which will be felt among all their suppliers. The danger for component suppliers is that while they may have to have the infrastructure to be able to supply their customer globally, and a commitment to research and development (R&D) to make the products attractive to the customer, the price received from the customer does not enable them to generate an appropriate return on the extensive assets required or compensate them for the costs involved. Therefore it costs a lot to secure this contract but the pressure on prices may mean that profitability is severely affected. This may not be an attractive situation for an investor.

Where distribution is more fragmented and customers are placing relatively small orders with a limited number of suppliers, the power may rest with the manufacturers.

Regulatory issues

For some sectors, such as utilities, there may not be any direct competition. To prevent monopoly profits the government may restrict pricing freedom by imposing a cap on price or restrictions on the returns the industry can generate. This is done by appointing a regulator who will determine the prices and returns that the industry can achieve in the absence of competitive pressures.

What is the outlook for costs?

Given the impact of globalisation and an increasingly competitive environment, tight cost control and an ability to manage costs effectively are a key requirement for any company. In addition, a much stronger position is established where a company can differentiate its product so price is not the major consideration when customers buy.

The costs an industry faces are often broken down into three categories: variable, fixed and sales.

Variable cost

The cost of raw materials is a variable cost because it will rise and fall depending on supply and demand in the raw materials’ market. Where variable costs are a large proportion of the overall costs, the investor needs information about the outlook for prices of the raw material in question. For example, the plastic pipe industry will see its profits significantly affected by movements in PVC prices, so some research into the outlook for PVC production would be useful. Fuel costs are often a significant proportion of overall costs and may need watching. Rising fuel costs adversely impact the airlines sector. A key issue is whether these cost increases can be passed on to customers, which will be dependent on several factors.

Fixed costs

One of the most important factors an investor needs to understand is what proportion of an industry’s costs are fixed. In a sector where fixed costs are a high proportion of overall costs, small movements in the volume of goods (or services) sold will have a relatively big effect on profits. One aspect to watch out for is a tendency for a management with high fixed costs to adopt a strategy of selling large quantities of goods (high volume) to spread the costs. To do this it may be tempted to drive down the price. However, competitors may retaliate to regain market share, leading to a price war in which only the consumer wins.

In some sectors, such as the service sector, wage costs can be a key fixed cost. If there is a scarcity of the skills needed to perform this service, costs may rise sharply. An obvious example is the football sector, where shareholders have suffered as players have prospered.

The balance between fixed and variable costs is an important relationship. This determines what is called the ‘operational gearing’ of the sector and tells you the relationship between a change in revenues (price × volume) and the impact on profit. For high fixed cost companies, say those involved in manufacturing, a small fall in revenue will have a significant impact on profit. A 5 per cent revenue fall might lead to anything up to a 40–50 per cent fall in profits. The impact is greater if the fall in revenues is driven by a reduction in price. There is a fuller discussion of operational gearing on p. 219.

Sales cost

The third main element of costs is sales costs. These are important in assessing the cost structure of a sector to get a feel for what proportion of overall costs needs to be spent on advertising and marketing, or research and development. These costs can be high when supporting an existing brand/consumer good is important, when new product launches are a regular feature or in a start-up situation. Many internet companies, which had relatively low fixed and variable costs, had a very high level of sales costs.

These costs are discretionary costs – they can be increased or decreased as the company sees fit. In a recessionary period a company may be able to cut back on sales and marketing without severely undermining its long-term competitive position. However, the company needs to be sure that it will not lose competitive advantage.

The net effect of demand, prices and costs is to determine the profits and returns of the sector – which is what you are investing for.

General economic and stock market factors – how do they affect the sector?

Defensive v growth sectors

Knowing where we are in the economic cycle and the outlook for economic activity is an important factor in determining the attractiveness of a sector. A period of rapid and sustained economic growth, such as that which occurred during the mid- to late 1990s, will tend to favour growth-oriented stocks. This was indeed a period in which growth stocks outperformed value stocks, with the value stocks tending to occupy the more cyclical or low-growth areas of the economy.

The deteriorating economic environment, especially for companies supplying the corporate sector, has severely undermined the attractions of growth. The extent of the indebtedness facing the corporate, consumer and government sectors, combined with the poor position of the banks, means that the shape of any economic recovery is even more difficult to predict than normal.

This has been an environment for more ‘defensive’ stocks, i.e. stocks that are traditionally considered to be not materially affected by the economic cycle. They should face a steady outlook for demand and prices. Often they are focused on the domestic economy and not subject to pressures from exchange rates/imports. Examples of defensive stocks include: food manufacturing and food retailing; pharmaceuticals, utilities (note that political/regulatory risk is important in these two areas); and tobacco (where political/litigation risk is a major concern). These areas have on the whole been very good for investment since 2000, with tobacco a notable winner. The issue then becomes, given their excellent performance over recent years, whether the ‘defensive’ element is already in the price.

The difficulty for these areas is that demand tends not to grow as the economy/people’s incomes grow – they become a lower proportion of household expenditure and the economy. It is difficult to see long-term growth for these businesses. Nonetheless, in difficult economic circumstances their attractions are clear. The low growth is outweighed by stability. In addition, the financial attractions of being in a defensive or mature area of the economy can work to shareholders’ advantage. Strong balance sheets and cash flow can either be used to invest in new areas of growth – for example emerging markets – or be returned to shareholders through dividends or share buy-backs.

There may also be specific difficulties for these sectors that undermine their defensive characteristics. This includes the purchasing power of the big food retail customers, which has caused margin pressure on food manufacturers.

A ‘defensive growth’ play, which is where growth is not dependent on the performance of the economy (e.g. in pharmaceuticals), may also look interesting in such an environment. Demand for pharmaceuticals is underwritten by an ageing population, the fact that using drugs is a much more cost-effective solution than hospitalisation and the need to alleviate illness and disease. These trends are relatively independent of what is happening to GDP. Risks tend to focus on the failure of drugs to gain regulatory approval, the number of drugs coming off patent, the length of time drugs spend in R&D, the recent lack of ‘blockbusters’ and the need for governments to control health care costs, which may lead to pricing pressure.

Impact of interest rates

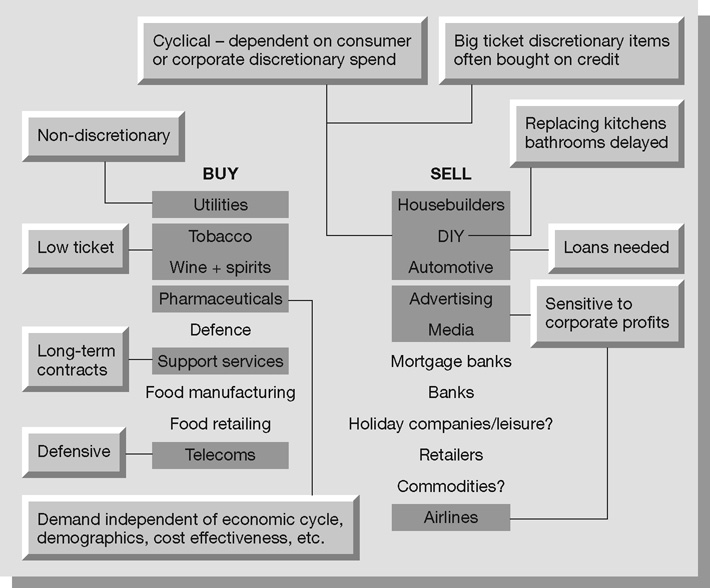

Falling interest rates will affect sectors in different ways. Housebuilders, for example, tend to have a strong correlation with interest rate trends, though in the current climate it is the availability of credit rather than its price that is the issue. See Figure 2.9 for various buy and sell options in an economic slowdown.

Figure 2.9 Sectors to buy or sell when interest rates rise (or no credit is available) and the economy slows down

The performance of cyclical stocks depends on the trend in the cycle and the trend in interest rates. While cuts in interest rates should benefit a cyclical stock, it may be that demand does not revive or industry overcapacity threatens pricing – the structural difficulties we referred to earlier. However, there is a ‘Catch 22’ situation for cyclicals with respect to falling interest rates. A cut in interest rates is good for cyclicals for the following reasons:

- Profits are very sensitive to GDP and falling rates should stimulate economic growth in time.

- Often these companies are highly geared financially so their interest burden is likely to be reduced.

Be aware though that the reason interest rates are coming down may also be important. If interest rates are cut because the economy is slowing rapidly and inflation is under control, this may well see volumes and pricing come under pressure. Deflation has been a particular concern to the manufactured sector for some time. Globalisation and the transparency created by the internet have been competitive and deflationary forces for many internationally traded goods.

This concern is particularly acute in the current environment – a downturn characterised by falling company expenditure, excess supply, inflation well under control and prices for many products on a downward trend. On the cost side these have been squeezed by higher raw material commodity and energy prices.

Growth

Falling interest rates are positive for growth stocks as they reduce the rate at which future earnings are discounted. Historically, growth stocks (and especially ‘cyclical growth’ stocks such as software) have performed well coming out of a bear market. This might suggest that good-quality, lower-risk growth stocks with some GDP sensitivity would be an excellent way of playing the current market recovery. This is, of course, subject to the caveat that this economic cycle is very different and overcapacity exists in many cyclical growth areas that may weaken the earnings recovery this time round.

The investment style guide (p. 301) provides more on the pros and cons of defensive and growth stocks/sectors.

Global sectors and currency

Increasingly, due to globalisation and the consolidation of many sectors, it is becoming less and less appropriate to think about sectors on a national basis. Sectors are being driven by events and developments all over the world. The technology, media and telecoms (TMT), pharmaceuticals, oil, automotive and chemicals sectors, to name but a few, are all increasingly international. This has profound implications when examining trends and valuing these sectors (which we will turn to later). As a matter of interest the investing institutions have adapted to this environment by increasingly looking at sectors on a global basis (or at the very least a pan-European basis). Many of the larger US investing institutions are already structured along these lines.

With this perspective, looking at and/or comparing GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca in the UK context may not be appropriate when there may be more attractive, better-value opportunities in the US or European pharmaceuticals sector. This may be important if it is a sector with overseas exposure. Different constituents will have differing exposures to the various regions. This may well be relevant to your decision in that you may feel that prospects are better in, say, Europe than in the US. It will also be important in terms of the impact of currency movements.

The impact of currency

When assessing the impact of currency it needs to be established how currency movements affect the company or the sector. There are two key ways in which profits are affected by currency movements, normally referred to as the translation and transaction effects.

The translation effect

This is straightforward as it is simply the impact of a rising or falling domestic currency and how it affects the recording of the profits of an overseas subsidiary. Let us take a company reporting its profits in sterling with a substantial part of its earnings from European subsidiaries. If the euro is very weak, profits will be lower when translated into sterling. Conversely, if the euro were to strengthen, profits might rise.

These movements may be mitigated by a company’s hedging policies. It may be that the company has a lot of euro-denominated debt. Then the servicing cost of that debt would fall, which would reduce the impact of the currency depreciation. The company might also enter into contracts in the currency markets by buying or selling the currency in the futures market.

The impact of translation on a share’s value should be relatively short-lived as the movement may be a one-off boost (or reduction) to the company’s profits. In that sense the improvement is a low-quality source of earnings (see earnings quality on p. 13). If you choose to gain overseas exposure to a particular country or region you should do it on the basis that the prospects for volumes and prices in those regions are attractive.

The transaction effect

The transaction effect is far more complex and can have a profound impact on the value of the business. This is because it affects the competitive position of the company. It also affects those sectors which deal in internationally traded goods and sectors. Manufacturing sectors such as engineering and automotive are the most obviously affected.

If the domestic currency strengthens, imports are more competitive and exports less so. This leads to a decision for the domestic producer – whether to lower prices and protect market share or to try to maintain prices and margins. This is a difficult decision and will depend on a number of factors, such as how big a threat import competition is going to be and whether importers, distributors or consumers will be attracted to these products. It may be that increased promotional spending will highlight the benefit of the domestic product or will try to get customers to focus on non-price areas of competitiveness. This marketing will reduce margins at least in the short term, but with the obvious intention of protecting longer-term market share and seeing off the import threat.

If prices are cut, the impact on operating margins and profits will be severe. If volumes fall, profits will also fall but perhaps by not as much as allowing prices to fall. However, as always, it is not as easy as that. Once market share is allowed to slip, there is the danger that importers will use this base to take even more market share.

Many of these issues are of a long term-nature and will be more costly if there is a prolonged strengthening (weakening) of the domestic currency. In a worst case scenario this could see the progressive erosion of market share for the domestic companies.

As the transaction effect could have such a profound impact on sales, long-term market share, operating profits and operating margins of a sector, it clearly could also have an enormous effect on its valuation.

Summary

The impact of the current economic downturn upon certain sectors has been very marked. Those sections of the economy exposed to interest rate rises and slowing economic activity such as banking, automotive, steel, housing, business travel and media (through advertising cut-backs) have been particularly hit. This is especially true when we are talking about ‘big ticket’ items (a house, a car, new kitchen or bathroom) that are financed with a loan. Conversely, low-ticket items that are ‘defensive’ such as utilities, food retail, alcohol and tobacco have held up relatively well.

Therefore having an appreciation of how the economy impacts on a sector is vital. This sets the ‘macro’ context within which a company is operating and will determine the amount of activity in a sector that will influence how much it sells (volume) and at what price.

The other key aspect to be aware of is the competitive structure of the industry. Using Porter’s five forces model we can get a strong sense of the likely pricing and margin environment for the company. This model also allows us to analyse how those forces are changing or may change in the future: Are new competitors emerging? Are customers and suppliers consolidating? Is a major player looking for market share or to generate cash?

Taken together, demand, prices and costs determine profits. Understanding the outlook for each of these elements in your chosen industry will give you a strong background against which to begin the analysis of your target company.

SECTOR CHECKLIST

Demand

- Is it a growth, mature or cyclical sector?

- How do movements in interest rates and GDP affect it?

- If cyclical, is it the business (capital expenditure) or consumer cycle that drives demand/profits?

- How discretionary is this expenditure?

- Is it ‘high ticket’ or ‘low ticket’?

Pricing

- How consolidated is the sector?

- What are the barriers to entry and how high are they?

- How powerful are its customers?

- Is there overcapacity and/or fierce struggles for market share?

- Is there significant international competition in the sector?

Costs

- How operationally geared is the sector?

- Are trends in raw material costs likely to make a big hole in sector profits?

- Are employment costs a key component and are the skills scarce?

General economy and stock market influences

- Is it a defensive or growth sector ⋖ how will it perform in difficult economic environments?

- How is it affected by interest rates?

- Are there structural factors such as overcapacity as well as cyclical factors that need to be considered?

- Is the sector dominated by a few major companies?

Is it a global sector?

- How do currency movements affect the sector?

- Does this impact on the translation of overseas profit or on the competitiveness of the sector (transaction effect)?

- Is political and/or regulatory risk a feature?