LEVERAGE 7

A pessimist sees the difficulty in every opportunity. An optimist sees the opportunity in every difficulty.

—Winston Churchill

WHAT IS “LEVERAGE” AND WHY IS IT IMPORTANT?

WHAT IS “LEVERAGE” AND WHY IS IT IMPORTANT?

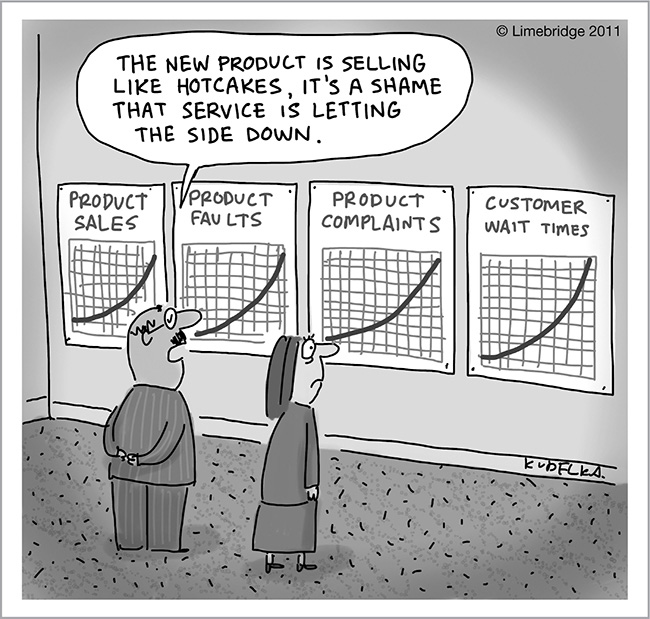

The final strategic action is Leverage, and it addresses reasons that are valuable to the customer and valuable for the organization. By definition, every organization wants more Leverage contacts, should invest time in them, and may want to increase their frequency. Customers don’t see these contacts as friction because they value them, and the organization knows that these interactions are often key to revenue, retention, and relationship-building with the customer.

Some of these reasons represent moments of truth1 for the customer, such as hardship or the start of a complex insurance claim. As such, both the customer and the organization should be prepared to invest time in these interactions to get successful outcomes. For the organization, there is significant potential return from these contacts through increased revenue, cost containment, and/or reputation preservation. Therefore, organizations should be prepared to invest in technology solutions, extend interaction times, and dedicate their best staff to contacts with these reasons.

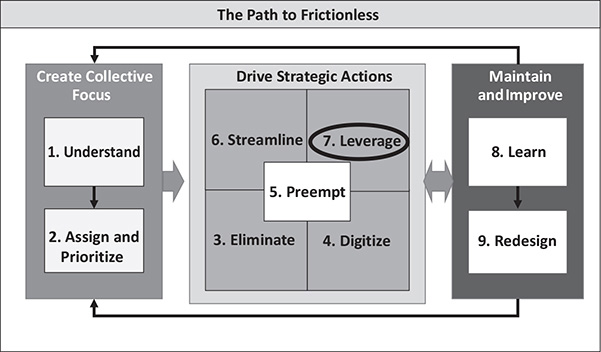

There are two steps to executing the Leverage strategic action:

1. Determine which contact reasons and which customers are to be treated as Leverage interactions. Understand and Assign may have led to an initial allocation of some contact reasons to leverage, but those contact reasons alone may not be sufficient justification for Leverage treatment. Making decisions about those contacts can be further complicated by the value of the customer, the contact channel, and the customers’ circumstances.

2. Figure out how to deliver the experiences that the customer and the organization want. This is where Leverage differs from the other four strategic actions (Eliminate, Digitize, Preempt, and Simplify) because there is no intent to displace or reduce these interactions. Here the focus is about how to make the most of the interaction and achieve all the outcomes that the organization and customer are seeking.

As for the first step, it’s complicated to identify Leverage reasons because they have four distinct dimensions:

■ Type of contact. For example, “I want to cancel” may be a Leverage contact, but “What’s the status of my cancelation?” usually requires Eliminate, Digitize, or Preempt.

■ Channel. The same contact reason may be seen as an irritant by the organization in one channel but not in another channel. For example, some organizations want more interactions using chat and messaging and now see certain interactions as irritants if they come by phone. Some organizations offer different channels to different groups of customers, so this becomes quite a complex decision-making process.

■ Customers and their value. High-value customers may be given premium service levels that enable them to contact the organization for any reason via any channel. In contrast, low-value customers may be restricted in the channels they use and for certain interactions (e.g., they may be expected to purchase and cancel via digital channels only). The how-to section of this chapter will describe some of the complexities of determining customer value.

■ Situational urgency and impact. There may be times when an interaction becomes more valuable to the organization and customer. For example, if a customer fears potential fraud on a credit card, their bank may want to receive immediate notification and to talk to the customer to ensure risks are managed. In contrast, if a customer damages or breaks a card, digital channels may be best since there is no risk of financial loss.

Analyzing contact reasons, channels, customers, and impacts is a complex process, and it might lead some organizations to leverage a combination that other organizations decide to digitize. Different markets or regions might assign different strategic actions to the same combination based on maturity levels, the trade-off between revenues and costs, and the available staff. It is not easy to separate particular groups of customers or to divert certain reasons to certain channels, leading organizations to apply one-size-fits-all solutions, such as sending all customers to a save team, even though they would prefer to apply that treatment only to the most profitable customers. They might not want to retain the bottom 20% of customers at all, but their processes and systems don’t enable rapid differentiation.

What Experiences Are Needed for Leverage Contacts?

The second step of Leverage is to design and deliver effective experiences that meet the organization’s and customer’s objectives for these reasons. This is a problem that can require design and implementation across a variety of operating model dimensions, such as well-designed processes, the use of appropriate technology, and the allocation or equipping of staff suited to the nature of these contacts. When the reasons being addressed are critical to revenue and reputation, most organizations are prepared to invest more in the design and delivery of effective interactions.

For Leverage contacts, it is also important to understand why they occur. For example, if customers are asking to leave, what issues and problems brought them to that point? Leverage contacts can also have addressable root causes that need analysis, and the how-to section covers that approach.

What Are Typical Leverage Reasons?

In general, contact reasons to address with Leverage are those that can produce significant financial or relationship impacts, falling into five likely themes:

■ Contacts that have the potential to produce greater revenues, including new sales or sales extensions:

❍ “Tell me about your new products.”

❍ “Can I extend my membership (or lease)?”

■ Contacts related to debt or credit risk, sometimes as a result of customer hardship:

❍ “Can I get on a payment plan?”

❍ “I’ve lost my job. How can I keep X?”

■ Contacts that may require preserving the relationship, such as saving a customer who is requesting cancelation, price-matching for a customer to counter competitor offers, or rightsizing the customer to a more appropriate product:

❍ “I need to cancel my account.”

❍ “This plan is too expensive for me. Is there anything else?”

■ Contacts that alert the business to a possible fraud or reputation risk:

❍ “There is something strange on my account.”

❍ “Did you send me this?”

❍ “My card may be stolen.”

■ Contacts that initiate expensive, long, and complex processes:

❍ “I want to make a claim on my income protection insurance.”

❍ “I was in a bad car accident.”

❍ “We need to restructure our business with you” (e.g., a B2B situation).

GOOD STORIES

GOOD STORIES

There are many good examples where organizations have invested in delivering excellent experiences when dealing with Leverage contact reasons. All of these stories manage to strike a balance among cost, customer experience, and revenue outcomes.

Leveraging Sales to the Max

The Royal Automobile Club of Victoria (RACV) is an example of a mutual fund that has grown in breadth and depth despite, or perhaps because of, competition from listed businesses. Each state in Australia has a similar member-based organization that provides roadside assistance services and insurance products; RACV also offers lifestyle and resort options. Its insurance business had a specialist sales team to leverage inquiries from members and non-members looking for insurance products. The business was looking for ways to improve its sales conversion rate and the value of sales. They followed a textbook approach with these three steps:

1. They analyzed current calls and the call-handling process, revealing which conversations were frustrating for customers and for the RACV (e.g., customers would get deep into a conversation and then reject a quote because it was too high). Few customers selected the extended product features, and frontline staff seemed frustrated and disengaged by the process they had to follow.

2. They redesigned the process by balancing the customer experience with the desired business outcomes of high sales conversion and throughput. The revised processes turned the conversation inside out: RACV provided the customer with a low, competitive quote as quickly as possible and then “earned the right” to offer extended features for the product. Staff were excited when they were trained on the new process.

3. They conducted a short pilot that led to an immediate step change in sales conversion.

These changes improved product margin with shorter conversations with fewer discounts. RACV saw a significant rise in the sales of higher-value products, and since the process was quicker, the sales team had more capacity. The customer reaction was also positive. In post-contact surveys, there was a 7-percentage-point improvement in customer satisfaction after the new process. Presented to the board as one of the most successful projects of the year, this project saw an overall gain in sales, margin, and sales productivity of over 40%.

Online-to-Independent Dealer

Trek Bikes makes some of the most popular recreational and competitive bicycles in the world. Like many other successful manufacturers, Trek had built a loyal independent dealer network over the years to sell and service its range of bikes and associated gear. When Trek decided to go direct to consumer (DTC), however, the company faced a dilemma: How could they build an even better relationship with its riders but not alienate its loyal dealer network? Trek took a novel approach to this dilemma. When the company designed its online product search and sales feature (using Digitize), it required customers to pick up their assembled and tuned bikes at nearby dealer shops (using Leverage). This multi-action, omnichannel strategy recognized that the post-sale activity represented an opportunity for dealers to develop relationships with customers, offer them accessories and clothing, and set them up with services and maintenance. Far from upsetting its retailers, Trek managed to pull off its online-to-dealer strategy to great success and has now opened its own branded shops without upsetting its traditional dealer network. In effect, Trek put the fulfillment stage of the sales process into the dealers’ hands.

Making the Claim

Automobile claims, especially those involving personal injury, represent some of the most sensitive and fraught cases for customers—and too often, there is considerable friction involved in the claims process. One of the many reasons USAA Insurance enjoys the highest customer loyalty of any U.S. property and casualty insurer (its NPS is in the high 80s, and its number one reason for churn is death, not going to another company) is the ease of its claims experience. Using a combination of online tools (Digitize) and well-timed outbound calls with USAA members (Leverage), the company keeps members informed throughout the complex claims process. As with all claims, USAA needs to know details about the location, timing, and situation. By enabling a member to upload photos (of the auto accident and damages to the involved vehicles) and to provide detailed maps showing the situation that led to the accident, USAA is able to analyze the data offline. After that, USAA arranges for a conference call with the member to confirm details and discuss options. USAA then keeps the member informed of claim details in its online portal, inviting the member via text message or email, whichever channel the member requests. This Preempt tool also reduces the urge for USAA members to call the company with “What’s the status?” questions. USAA balances and stages each of the strategic actions during the claims process, using Leverage for the most sensitive moments for the member.

Value-Add Conversations

Vodafone Portugal believed that there was greater potential to have value-add conversations on certain contacts. The marketing analysis team had already assessed which additional products were suited to customers. Some initial research also showed that customers were actually more satisfied after calls in which additional offers were well explained and matched, even when they didn’t take up the offer.

The contact center conducted further analysis to assess which calls really were in the Leverage quadrant. They recognized that attempting product conversations on Eliminate reasons was a waste of time. Their analysis of current calls showed that around 20% of them fell in the Leverage quadrant. They then worked with frontline staff to design these conversations. That produced another interesting finding: staff didn’t want to be constrained by just one marketing offer in a conversation; instead, they wanted to be empowered to pick from several options.

As a result, their design of Leverage conversations included trigger statements that staff could look for before initiating conversations. This meant the conversations were targeted to customer needs. New conversation guides also helped staff explain product options and benefits, gave them ideas for handling objections, and offered other tips that helped them to be well prepared for any negativity and to offer better explanations. The company trained several pilot teams in this new way to handle Leverage calls. The results were quite remarkable. The pilot team made 6 times more offers than with the old process, producing 10 times as many new products or changed-product sales. Better still, tNPS increased with the new process.

Far from being “Do you want fries with that?” conversations, the new Vodafone Portugal offers and explanations were made at appropriate times. The company was elated with the associated revenue gains, and staff benefited through aligned and increased commissions, a good example of a triple win (for the organization, customer, and staff) achieved through designing Leverage calls that would benefit all parties.

BAD STORIES

BAD STORIES

Falling down the Cracks

The major earthquake in Canterbury, New Zealand, in 2010–11 left many homes unlivable and created more than 650,000 insurance claims valued at NZ$21 billion. Insurance customers needed support so that they could get on with rebuilding their homes and lives. Some companies responded well, sending extra assessment staff to Canterbury or waiving some of their normal rules to enable claims to be fast-tracked. Unfortunately, that wasn’t a universal story. Over the next few years, stories emerged of customers still in dispute with their insurance companies over their claims. They had been unable to proceed with rebuilding their homes or buying new homes because of delays and disputes in the claims process and the complexity over deciding whether they should be allowed to rebuild in quake-ravaged areas.

Rather than being flexible and responsive to a clear Leverage need, one or two insurers seemed intent on making the claims process as long and drawn out as possible. This led to newspaper and TV reports exposing these companies. Several ended up in claims tribunals, which extended the process further. The problem became so bad that the New Zealand government stepped in with extra quake support and proceeded with major legislative reform to prevent these situations in the future. Even as late as 2019, however—eight years after the earthquake hit—the NZ Insurance Council reported 1,100 claims still incomplete. Unfortunately, there was limited publicity naming and blaming these companies, so they remain in business today.

Channel Trapping

There are times when certain channels are ineffective at handling contact complexity. For example, many organizations are using email less or have stopped it completely because it can produce drawn out and ineffective interactions.

In one instance, a business utility client was trying to get a new meter installed to support a new site. This is an example of a Leverage contact, as it represents extended business for the utility and is important for the customer. The business customer emailed the request, including the site details, and attached forms for the associated process. Twenty-six email messages and two months later, the meter installation was still not arranged or complete. The customer was very frustrated at the process and at being unable to rent out the premises.

The emails were handled by up to four different staff members in the utility, all of whom could see the whole sequence if they looked hard enough. However, at no point did an agent call the customer or seek to switch to a more direct and complete way of communicating. Neither was there a clear directive to resolve the contact by phone, which no doubt would have been a more effective mechanism.

Order Taking

A small telco offered competitive plans for mobile and broadband and had a smart strategy to target regional and rural customers who wanted an onshore sales and service experience. Many customers would call the sales team with clear Leverage statements like “I think I want this plan” or “How do I sign up?” These calls landed in the laps of the sales staff, who easily converted over 40% of the calls. Unfortunately, though, a poor sales process produced terrible post-sales experiences. The company averaged over three service calls for each new plan sold, and it lost over one-fifth of those new sales within three months from disappointed customers.

A detailed Understand study showed why the company saw these outcomes: the sales agents did a poor job of listening to the customer’s needs. If a customer asked for a product, the agents gave them that product without checking the customer’s requirements. The sales reps also knew little about the post-sales processes. They didn’t explain how and when the customer would get connected or set them up to pay bills in an efficient way. The sales reps merely took the orders. Customers, therefore, called in later, confused about connection speeds, the connection process, and why they were being billed for certain features or products. Many downstream contacts could have been avoided had the sales team explained the process and set expectations up front. These were Leverage contacts handled with a bare-minimum approach that delivered poor outcomes.

HOW TO LEVERAGE

HOW TO LEVERAGE

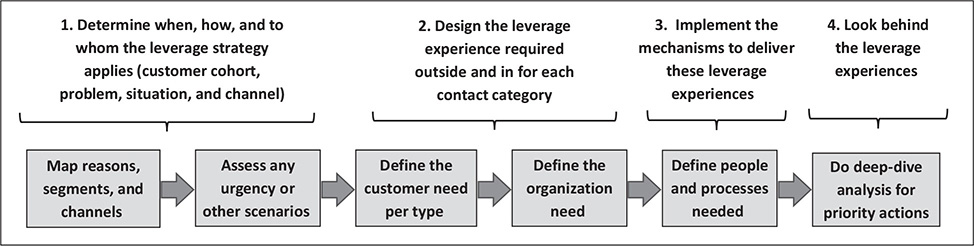

As shown in figure 7.1, the Leverage strategic action first considers which interactions to leverage, for which customers, and then it looks to design and deliver appropriate Leverage experiences.

Determine When, How, and to Whom the Leverage Strategy Applies (Customer Cohort, Problem, Situation, and Channel)

It is not easy to determine which contact reasons should be given Leverage and treatment, especially when also considering different customer segments in different circumstances. This becomes a multidimensional problem once organizations offer numerous contacts channels that vary in cost and effectiveness for different contact categories. A good way to start this analysis, though, is by considering (1) the type of contact (e.g., revenue generation, service, risk, or fraud mitigation) and (2) the value of the customer.

For any contact reason, there is usually a healthy debate as to whether Leverage or Digitize is the most appropriate strategy. For example, for “I want to learn more about your new products,” a digital Innovator might decide to steer all customers to the web first before talking with them, while an older-style Renovator might prefer to split customer segments and take their most valuable customers into the assisted channel while the rest remain in digital channels.

Most organizations segment their customers by current or potential value.2 Leverage considers whether the organization wants to treat these segments differently and, if so, what that would mean in terms of what channels are offered, what differentiations should be made, and whether frontline staff should be deployed to handle these interactions. For example, airlines might offer separate phone numbers for premium frequent flyers to connect to a special service team composed of the most experienced staff, while referring the mass market directly to websites and chat.

Even where differentiation is desirable, an organization still needs to ask whether it can apply different treatments or whether doing so would just be too hard and complicated. Most organizations have to apply broad-brush approaches to this problem because they can’t easily distinguish between different customer segments and needs “on the fly.”

FIGURE 7.1. Leverage Approach

An organization should also recognize the relationship between the value of customers and the cost it is willing to pay to provide various channels. The value of the different customer segments will determine which channels the organization may be able to offer profitably for different types of interactions. Low-value customer segments may only be profitable if they aren’t handled by assisted contact channels, even for Leverage interactions like sales opportunities. For example, prepaid mobile customers (usually a lower-value segment) may only get access to automated sales and service channels such as apps.

One way to simplify this multidimensional problem is to use a matrix of three “buckets” of typical customer interactions: Joining, Maintaining, and Leaving. This helps paint the broad strategy; then the organization can add more detail to the contact reasons in each stage. In table 7.1, the Digitize opportunities are shown in plain text and the Leverage opportunities in bold italics.

This matrix illustrates the potential mix of Leverage tactics in those instances when an organization wants to offer assisted contact versus digital strategies for lower-value customers and interaction types. In this scenario, the organization is prepared to invest in the Silver segment to initiate the relationship and preserve it, but routine maintenance is handled by a digital strategy, except for urgent reasons. The Gold segment can choose between assisted channels or digital self-service. Their higher value means that the organization views all contacts with this segment as being leverageable.

TABLE 7.1. Example Segment Strategy: When to Leverage or Digitize Leverage = Bold italics; Digitize = Plain text

Many banks follow a strategy similar to this. For their highest-value private-banking segment, they offer a one-to-one relationship with a personal banker and a bevy of wealth managers. These bankers handle all of the customer’s needs, including routine maintenance transactions. In effect, the bank sees all interactions with these customers as valuable and worthy of this Leverage treatment. In contrast, a customer with a simple checking account might have a limit on which transactions they can complete in branches or by phone. Some banks even charge for interactions over a certain limit. Since most banks now offer online banking and mobile phone apps, they expect the majority of customers to use them for routine transactions.

It can be oversimplistic to look purely at the economics of the customer relationship to determine how a particular contact should be treated. For example, a customer in difficult circumstances may need hand-holding regardless of their value to the organization. The urgency and need of the customer can change the importance of the issue for the organization. Even routine transactions, like bank withdrawals or mobile phone-balance top-ups, can start to incur a reputational risk if the organization doesn’t handle them efficiently and effectively when the customer is in a difficult position. For example, in weather-related crises, many organizations offer additional help and support. During these crises, banks waive overdraft rules, and utilities extend payment terms. This happened during the bad Australian forest (bush) fires of 2019–20 and in the wildfires in Portugal and on the West Coast of the United States. Many organizations offered extra support to their customers financially and through special help and support lines that bypassed normal queues and treatments. This is a good illustration of customer urgency outweighing other issues. Regardless of whether organizations do this merely because it is the right thing to do or because of the possible reputational benefits, the outcomes are still positive.

Design the Leverage Experience Required Outside and Inside for Each Contact Category

Customer contact reasons that require the Leverage strategy tend to be more complex by nature than routine transactions. They are also more complex contacts that involve getting simple information, which are addressed with Digitize actions, or ones that can be eliminated or preempted. Leverage interactions are often the hardest interactions to manage well and thus need effective experience design both for the customer and the organization. Interactions with a revenue element, such as new sales, upsells, and saves, often also face regulatory scrutiny in some industries. Consumer law may protect customers from aggressive selling, misleading sales, or overly aggressive retention tactics.

Saves and cancel transactions illustrate a delicate balance between customer and organizational needs. Customers calling to cancel an account want the interaction to be quick and painless; they want to be in and out as fast as possible. By contrast, the organization is often looking to save the customer and retain the revenue. Many organizations use deceptive practices when customers attempt to cancel their contract, telling the customer they will be sent to the cancelation team when they are actually sent to a special “save team,” whose performance is measured on their save rates. A well-designed save conversation recognizes this balance of needs. The save team may be able to repair a problem that has led to a cancel request or match a competitor offer, but they should also be good at understanding why a customer wants to leave and stop trying to save customers who are clearly in no mood for an extended conversation.

Hardship conversations are also a juggling act. If a customer can’t pay a bill or can no longer afford a product or service, the organization should balance their financial exposure to this customer with other factors, such as reputational risk. In most countries, utilities like electricity and water are seen as essential services, so organizations have to offer hardship schemes that balance trying to get payments in the door with customers’ needs, including distressing circumstances. Information and history about the customer can help. If this is the first time a customer has sought relief, it’s very different from a customer who never pays on time. However, even the chronic late payer may have extenuating circumstances. These conversations have to be well structured and must be handled by frontline staff who have information at their fingertips and a range of options to apply.

Complex claims issues are another illustration of the need for well-designed conversations. At the start of a claims process, customers may be in trying circumstances (e.g., damage to their home or car, an illness, or personal bodily injury). However, the insurer is trying to move the customer down a certain path to control the cost and duration of the claim. In many situations, the customer’s and the organization’s need are aligned. Getting the right treatment early can help the customer recover faster and contain claim costs. There are also benefits to advising the customer in the right way, which should align with the organization’s need to contain the cost of the claim. The claims conversation needs to have a well-defined process so that staff can explain the process and advise the customer appropriately. There are many systems that can assist with this kind of conversation. For example, well-designed knowledge tools, especially with AI and machine learning, can help the claims agent identify the customer’s medical condition and recommend appropriate treatment paths.

Implement the Mechanisms to Deliver Leverage Experiences

To help deliver the Leverage experiences they want, organizations typically draw on combinations of people, technology, and processes. We explore each of these areas next.

■ People. It is one thing to design the experience for Leverage contacts, but it is quite another to execute it—and execution is critical. A key part of the execution is assigning the appropriate individuals to handle these contacts. That might be as simple as getting the customer to the hand-picked and specially trained hardship team. In areas like sales, however, or for higher-value customers, it might be better to match the best skilled or tenured agent with the customer.

Larger organizations, in particular, may have the luxury of matching agents to customers via several new methods, such as assigning certain frontline staff members to particular customer personas. To do this, they classify certain needs and characteristics of customers into definable groups that help clarify the way they should be treated. If done correctly, this can help the frontline agents handling the contacts to recognize the broad needs of those groups and ways they generally want to be treated. If interacting with a customer who fits the “Information Seeker” persona, a staff member knows to tailor the conversation to provide lots of explanation; but if speaking to a “Bargain Hunter,” they know to simply inform the customer of the best offer available as quickly as possible. Further, matching staff members with customers who share their attributes can help staff empathize and better serve their needs. As organizations get access to increased amounts of data about customers, their ability to classify and tailor the experiences should increase.

One large BPO claimed good results from attempting demographic matching of customers to their sales and service team. Wherever they could, they tried to route calls from customers to agents with a similar demographic profile that took age, marital status, and family status into consideration. The organization had sufficient scale to achieve this level of matching 60% of the time and compared the revenue results of matched calls versus unmatched calls. They reported increased revenue of 45% per call on a combination of sales and service calls.

■ Technology. Technology can play an important role for Leverage reasons (e.g., with hardship or saves), making it important for staff to have a well-analyzed history of clients’ prior relationships. The best technology solutions, such as augmented agent technologies, recommend offers to make or other actions to take. In save environments, technology may suggest alternative products that the customer can afford (e.g., a lower price plan) or put a limit on the discounts or offers that frontline staff can give a customer (also called down-selling or, more accurately, rightsizing).

Technology can play an important role in augmenting Leverage experiences. Real-time speech analytics (analytics that assess a conversation as it occurs in real time using AI and machine learning) can enhance frontline skills. These augmented agent services can analyze the customer’s history to match them to alternative or additional products and services or serve up relevant knowledge articles and comparisons. In a save situation for a telecommunications company, the technology can analyze all aspects of the customer’s phone and data history to recommend alternative products that may fit their spend and behavior profile. This agent augmentation technology can suggest a range of products and even help the agent predict future bills, likely savings, and future purchases. In a hardship scenario, technology can calculate different payment profiles and plans and even suggest questions that the agent should ask to diagnose information that is important for the process. Some companies are even using technology to make individual offers tailored to a customer rather than making offers based on broad product groupings.

■ Processes. Well-designed processes become critical in Leverage interactions. In sales conversations, for example, the frontline staff need to be able to execute a range of effective processes, including the following:

❍ Build rapport with prospects and customers and listen to their spoken and unspoken needs.

❍ Probe for and diagnose needs for those products and services.

❍ Match needs to products.

❍ Tailor the offer.

❍ Overcome objections and obstacles.

❍ Convince and close.

Some staff will perform these tasks instinctively, but each of these sub-processes can also be defined, trained, and coached. Complex processes like claims can also be broken down and documented so that staff can be taught the best sequence of questions to ask to get to a good claims outcome.

Leverage execution requires this combination of people, technologies, and processes working in harmony to get outcomes that the organization and customer both want to achieve.

Look Behind the Leverage Experiences

While Leverage reasons are, in theory, ones that the organization wants to handle, some of the reasons are worthy of further analysis. That’s because Leverage contacts may also provide important insights into the organization’s core processes, pricing, and products. For example, if a customer asks to cancel, this may be the culmination of many failed processes—or it could be that the customer was sold the wrong product initially, has had a series of poor experiences, and/or received a more compelling offer from a competitor.

Many Leverage reasons require deeper root cause investigation to understand what is driving them. This process might identify that many customers are equally affected and could be handled preemptively. The examples that follow illustrate potential analyses of cancelations, hardships, and contacts with fraud potential.

Example 1: Cancelation mining. One large utility analyzed its calls to cancel service and realized that a competitor was bringing aggressive pricing to the market. However, they also noted that their offers had a limited benefit period. They equipped their saves team to educate customers about this short-lived benefit and worked up examples to show that their product was as cost-effective in the medium term. This helped lift their saves rate.

Example 2: Learning from hardship. One company recognized that they could learn from hardship-related inquiries. They went right back to the process by which they had acquired customers to analyze whether certain campaigns and processes had attracted customers who were more likely to end up in debt and hardship. They recognized that discount offer campaigns, which ran at certain times of the year in certain geographies, had a far higher propensity for those in hardship. They also had to balance this analysis to see if the ratio of profitable customers emerged.

Example 3: Preemptive fraud warning. Banks that experience potential fraud and customer scams now look to mine these contacts so they can build in early warning systems for their customers. One credit card company alerted their customers about potential credit card fraud from taxi companies. They had spotted a trend in which their customers would see many similar but fake deductions on their cards from taxi suppliers; these deductions would resemble their prior fares. The difference was that the fraudulent transactions had rounded amounts like $64, where most legitimate transactions were rarely rounded. In this way, the bank was able to monitor for these transactions and warn customers before the fraud mounted to large amounts.

HINTS AND TIPS

HINTS AND TIPS

The hints and tips for Leverage cover a broad range, from sales, to fraud and risk, to saving customers.

Provide Choices for Sales and Save Conversations

It is always a good strategy to offer customers choices so that they have control over their product-related decisions. A UK bank discovered this when the first digital sales solutions it created made a single recommendation to customers. Many of them walked away not trusting this apparent fait accompli. They reworked the solution to offer choices and got a much better result.

This idea in practice. A self-service web-based solution allowed customers to specify their needs for white goods. Even where the technology could have recommended only one product to the customer, the solution was designed to present at least three options so that the customer could choose. It did flag the possible best pick but allowed the customer to choose and provided a link to assisted support where needed. The application is now the best-selling white-goods website on the market.

Integrate Channels to Make It Easy for Customers

Leverage contacts are often lengthy and complex. Using a mix of channels can help customers make decisions in their own time and put them in control while making the process easier. That can mean using text and email messages to explain the organization’s processes to the customer or, if needed, creating a “trialogue” among the customer, the sales agent, and a digital sales platform.

This idea in practice. Customers often report motor accidents while they are in no position to remember details or even write them down. Many claims processes now use text and email to get the customer the information they will need, such as claim reference numbers, useful process details, and even links to videos and guides to help them. Having that information on their phone means the customer can easily reference it while dropping off a car at a repair shop.

Balance Trust and Risk for Hardship and Fraud Conversations

Hardship conversations (and some claims conversations) often require organizations to trust their customers’ information. This can be a delicate balancing act for an organization that may also be concerned about fraud or payment evasion. It’s hard for customers to admit to situations like being laid off, so this also has to be taken on trust. The savings in paperwork and effort, however, often outweighs any financial exposure.

This idea in practice. An energy utility changed its hardship process so that they could now accept certain information with few questions asked. They realized that customers very rarely lied about scenarios like being recently bereaved or unemployed, so they decided to take this information on trust: no death certificates, no intrusive need for government proof. The process was quicker and, when monitored, produced no change in the ratios of bad debt. In other words, they were right to trust the customers in these circumstances. It was a quicker process and less intrusive.

Value the Customer’s History in Key Transactions

Organizations hope for lengthy relationships and loyalty, and in certain situations, customers expect this loyalty to be acknowledged and rewarded. While it’s quite difficult to design processes in such a way that they flex to the length and value of these relationships, customers do often say, “I’ve been with you for a long time” so it’s not unusual for a 30-year customer to expect at least acknowledgment if not also forgiveness or greater leniency and flexibility in payment terms.

This idea in practice. Pilots at a well-known international airline went on strike. Their main competitor recognized a one-off opportunity to impress their rival’s most valuable customers with the benefits of a frequent flyer program: they threw open lounges and preferred seating to any of this competitor’s customers who had the equivalent status. In effect, they “status-matched,” offering frequent flyer benefits for one year to customers who came from their competitor and booked flights even after the strike ended. This showed customers that they valued frequent flyers and would welcome their business. This helped increase their market share of the most valuable customers.

SUMMARY

SUMMARY

Leverage enables the organization to move from cost containment and customer experience improvements to revenue enhancement, customer retention, and investment in long-term relationships. Deciding which interactions to address with the Leverage action is a complex and multidimensional process; it’s also a challenge to work out how to design and execute Leverage experiences successfully. Deciding what to leverage requires calculating long-term customer value and channel strategy and then analyzing what level of differentiation is possible. Building Leverage interactions needs careful design in terms of who handles the contacts, how the technology enables and supports them, and how the processes work. Frictionless companies design Leverage interactions that demonstrate an understanding of what makes them easy, providing choice, demonstrating when to trust customers, and conveying how to esteem lasting and valuable relationships.