3

Cultures and Languages in Contact: Towards a Typology

The Typological Thrust

When we consider cultures and languages in contact, two points become immediately obvious. First, the most insistent and the most salient contexts are those involving societies of unequal power and dominance. This suggests that special attention to those interactions involving minority groups will be the most revealing, if only because minority–majority relationships tend to throw into high relief phenomena that are sometimes not so clearly seen in less highly charged settings. Second, the uniqueness of every setting does not arise because the elements of it are found nowhere else – rather, it arises because of the particular combinations and weightings of features that are, in themselves, commonly observed across a range of social situations. And, when features and dimensions recur across contexts, it is surely reasonable to think about putting them into some typological order. Indeed, despite what some critics have noted (see below), it is hard to see how careful work here could fail to be useful. Even modest descriptive undertakings could repay the effort; as Ferguson (1991: 230) pointed out:

it is frustrating to read a stimulating case study and find that it lacks information on what the reader regards as some crucial points … what I have in mind is not so much a well developed theoretical frame of reference as something as simple as a checklist of points to be covered.

In this chapter, I focus mainly upon the linguistic aspects that Ferguson (and others) have dealt with, doing so in the belief that these aspects constitute a particularly important and revealing reflection of, and guide to, broader dimensions of cultural contact. What, then, are the chief sociopolitical aspects of language-contact settings? They involve the status, policies, planning, attitudes, and intentions of the communities involved. Specifics may vary enormously across contexts, of course, but there are generalizable features, too – and my suggestion here, as already implied, is that fuller investigation of these features might profitably take the form of a typology, a scaffolding that would include such dimensions as the geographical, historical, political, sociological, psychological, educational, and linguistic. Various typologies and part-typologies have already been published, of course; one thinks of the valued work of Ferguson (1962, 1966), Kloss (1967, 1968), Stewart (1962, 1968), Haugen (1972), and others. Since these have not been systematically exploited, however, the way is open for a more comprehensive approach, one that would integrate and expand upon such previous insights.

In formulating a typology, it is necessary to list, categorize, and intercorrelate – in a word, to attempt to understand – many factors, along the sorts of dimensions just mentioned. This would produce, in effect, a framework of variables that could serve to illuminate contexts of cultural and linguistic maintenance and shift. One could imagine, as well, that such a scaffolding could be used to inform and guide relevant policies. If communities are described in a formalized or semi-formalized way, they can better understand their own situation (and how it compares to that of others), and can more accurately present their “case.” In what follows, then, I make the assumptions that a comprehensive, multidisciplinary analysis of contact situations will be intrinsically useful context by context, and that emerging generalities may be found which will permit comparison and classification of different contexts under certain rubrics: anyone who has ever attempted a contrastive analysis, or who has cited different examples to make a general point, has in effect argued that some features are constant or at least similar enough across contexts to suggest useful generalization. I also assume that information thus obtained may produce a useful sociopolitical picture, particularly where majority–minority relationships are involved, and that this in turn might sharpen our sense of what is desirable, what is possible, and what is likely.

Not all commentators have seen typological excursions as worthwhile. In several reviews, for example, Williams (1980, 1986, 1988) questioned the utility of typologies. He claimed (1986: 509) that they reflect “implicit theoretical assumptions” while having only “limited analytical usefulness.” Two years later, he restated his case, adding that “I fail to understand the preoccupation of students of language with typologies” (1988: 171). Garner (2004: 197) repeated the criticism more recently, noting that typological categories “inevitably reflect pre-existing theoretical orientations” and are unlikely to lead to “new theoretical frameworks.” Such points are of some interest, but they hardly sound a death knell for typologies. All endeavors, after all, proceed from implicit assumptions, but the constraints that these imply can be greater or lesser depending, among other things, upon the comprehensiveness of the undertaking: a broader typology with many elements is more likely to be useful than a narrower approach. Also, whatever the verdict on the purely analytic utility of typologies – and recalling Ferguson’s observation (above) – simply having a broad listing of potentially important elements could well be worthwhile. My basic contention is simply this: since there is every reason to assume that people will continue to interest themselves in situations where cultures and their languages come into contact, and will wish to describe and account for them, since it makes no sense to assume that different contexts are entirely unique, and since we are inevitably and rightfully drawn to the task of theory construction (however informal), comprehensive and well-specified typologies may serve useful purposes.

Geographical Beginnings

Beyond some extremely basic approaches to geographical classification (e.g., Price 1973; Sikma and Gorter 1991), a noteworthy effort was that of Anderson (1980, 1981), who provided extensive descriptions of seven types of minority–majority contact situations. In the first category are language minorities found in their own homeland (Anderson cites the French in Canada and the Provençal community in France). The second comprises minority groups that are majorities in a neighboring country (his examples here include the Kosovo Albanians and the Flemish in northeastern France). Third, there are what Anderson calls “complementary” minorities on both sides of an international border (the Germans in southern Denmark and Danish speakers in northern Germany, for instance). In the fourth category we find “international” minorities, indigenous to a region that is, itself, divided between two or more states (the Sámi, for example, whose homeland extends across Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Russia). Category five is for those groups – like the Jewish and the Romani in Europe – who are widely dispersed. Anderson’s sixth category comprises “interrelated” minority groups: communities attempting linguistic and cultural revival in separate countries; he mentions Celtic revival here. His final category is for minority-within-minority contexts.

Further comments on Anderson’s scheme will be found in Edwards (2010). There are problems with all of his categories, but I will mention here only that size and status differences suggest that there is something wrong with categories that can include both Provençal and French, or both Albanian and Flemish. Anderson’s third grouping could be seen as a sub-category of the second, and his sixth – which he terms a “special case” – also involves populations that could easily be accommodated elsewhere in his model. The seventh, “minority-within-minority,” classification is often, indeed, the “most complicated,” and one of Anderson’s examples – English speakers in Quebec – obviously demonstrates this. At the same time, it illuminates a recurring difficulty in all frameworks where minorities and majorities come into contact: what might be termed the “frame of reference” problem. Are Quebec Anglophones best understood as a minority within a (Francophone) majority, or as a minority among Francophones who are, themselves, a minority within the larger Canadian collectivity? Much clearly depends upon whether one’s perceptual basis is Quebec or Canada.

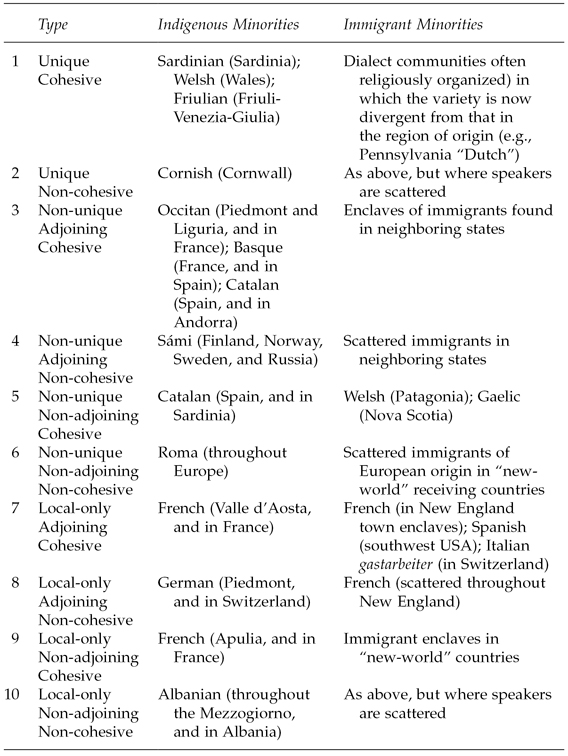

White’s (1987) approach to geographic typology is the one that I have used as a foundation for my own framework. His model possesses a greater internal “logic” than previous efforts, involving less overlap among categories. It is outlined along three basic dimensions. First, we must ask if the minority group in question is an “absolute” or “local” one. The former term refers to communities that are minorities in all contexts where they occur (some will, of course, be unique to one state). The second refers to varieties that have majority status elsewhere. I propose to term these variants unique minority, non-unique minority, and local-only minority. Second, we are to consider the type of geographical connection between speakers of the same language in different states: is it contiguous or non-contiguous? Having in mind the “tighter” and “looser” meanings that can apply here – where the former restrict contiguity to actual “touching,” while the latter allow mere “nearness” – I think that better terms would simply be adjoining and non-adjoining. White’s third dimension has to do with the degree of spatial cohesion among the members of a community in a given state. The terms cohesive and non-cohesive would serve well here.

Given that a distinction between adjoining and non-adjoining regions has no application for unique minorities, it follows that a ten-cell model emerges (see Table 3.1). White devised his system specifically for the Italian context, and the minority groups in that setting provided examples for seven of the ten possible cells. In expanding and making more general his approach, I have retained some of White’s Italian examples but have also included non-Italian instances; in this way, all ten cells can be illustrated. Further, while White’s presentation dealt only with indigenous communities, the extension shown here in Table 3.1 also provides immigrant-group examples. (Since, given sufficient time, immigrant groups may become indigenous ones, we might wish such an extension on practical as well as theoretical grounds; see also below.) It should be noted that the table lists only minority-group languages, omitting mention of the obvious majority communities that surround them.

Table 3.1 The geographical contexts of cultural contact (with some examples)

Source: Edwards 1992.

There are, of course, difficulties with this (as with any other) typology. For example, the cohesion dimension presents problems. How wide, for example, will we consider a region to be when attempting to distinguish between cohesive and non-cohesive populations? If, for example, a language was spoken sparsely over a wide area, but also possessed a center with a considerable concentration of users, then it might be seen as either cohesive or non-cohesive. While there are probably no situations which have a cohesive core without also being non-cohesive in some larger hinterland, it is perhaps possible for non-cohesive groups to have no cohesive counterpart at all (although even here there may be small and relatively cohesive pockets). Again, matters typically hinge on the scale that one wishes to apply.

Another difficulty arises when considering a group that is found in adjoining states. Each can perhaps be classified as cohesive or non-cohesive, but the degree of cohesion of the one across the border will also be important. Issues also arise concerning distinctions between adjoining and non-adjoining contexts in themselves. For Basques in France and Spain, the “adjoining” label seems appropriate, but what of communities that are found in neighboring states but not in their common border areas? Similarly, there is a difficulty with what we might style “degrees of indigenity.” The indigenity of the Welsh, Cornish, and Sámi, for example, may have a breadth and depth that can hardly be matched by (for example) the Greeks in Apulia, who descend from Byzantine invaders of the sixth to tenth centuries, or by the Albanians of the Mezzogiorno, who have been in the region for 500 years.

White argued that geographical factors contribute to the strength or weakness of contact settings, and thus to different varieties of political stability and expression – and my expansion of his model obviously indicates my agreement. But a geographical approach is best seen as the groundwork upon which further building can occur; by itself, it has quite limited utility.

Beyond Geography

Foster (1980) outlined a research agenda emphasizing three factors: history, economics, and subjective assessment. First, then, we require a categorization that goes beyond statistical analyses of populations, languages, and socioeconomic issues, to an investigation of the historical development of the political culture of the given regions. While examination of the historical record is essential, it is often either ignored or downplayed. This is largely because it does not yield “data” of a kind that can easily be built into the decontextualized exercises that are, unfortunately, so common in modern social-scientific enquiry. Foster also argues for more study of the relationship between economic factors and ethnic “groupness.” Again, I agree. We should pay considerable attention to economic and pragmatic matters simply because these are of pressing importance in the lives of most people. Many apologists for diversity rail against economic “reductionism” but analyses of movements for cultural and linguistic maintenance or revival generally reveal a powerful economic element (Edwards 1985, 1994). Thirdly, Foster writes that we should pay special attention to the subjective features of minority contexts, features that may be inadequately explained in more objective terms. Subjective assessments are of the greatest significance, to be sure, and any classification scheme that made no room for social and psychological perceptions would be crippled; see the notes, below, on “subjective vitality.” Feelings can also be studied historically, however, and survey research should thus always be accompanied by intelligent and informed inference. It is necessary to point out, too, that subjective feelings do not arise from nothing: studies of linguistic, economic, and other social perceptions must go hand in hand with investigations of realities on the ground, as it were.

Foster reinforces the general sense that any useful typology of cultural contact situations will be broadly based. And indeed, both before and after Foster wrote, there have been several notable attempts to come to grips with the factors he discusses. As might be expected, there is a considerable degree of overlap. This is not a criticism, of course, for it is an essential part of formal progress that previous insights are built upon by newer ones. I examine here several important typological models and comment upon the strengths and difficulties of each – this, by way of introducing my own framework. Not all of what follows, by the way, is necessarily restricted to minority situations, since many of the factors important to those settings will also be relevant in others. As I have already pointed out, however, the particular dynamics of minority–majority contact can often throw into sharp relief matters of much more general interest. The models here are presented in roughly chronological order of development, and I restrict my necessarily brief comments to the most salient issues.

Linguistic Categorization: The Work of Charles Ferguson and William Stewart

Ferguson (1962) suggested some very basic approaches to sociolinguistic profiles, arguing that information should be collected and collated concerning the number of major languages spoken in a region, the patterns of language dominance, the presence or absence of “languages of wider communication,” the extent of linguistic standardization, and the extent of written language.

Two publications by Stewart (in 1962 and 1968) bracket Ferguson’s work in the presentation of classificatory information about language types, functions, and degrees of use. As there is considerable overlap among all three, I provide here only a brief consideration of Stewart (1968). First, he outlines seven main language types: pidgin, creole, vernacular, standard (i.e., a standardized vernacular), classical (a standard no longer spoken), artificial, and dialect (to cover situations where a dialect enjoys special status). Stewart also specifies several degree-of-use categories – percentages, that is, of speakers of given languages within states. He then turns to language functions, outlining ten categories involving regional and contextual factors. Thus, he mentions provincial, capital, and international varieties, as well as languages used particularly in educational, religious, and other settings.

It is apparent that the use of Stewart’s dimensions and categories – or others like them – could be quite helpful in coming to grips with language and cultural contact settings. It is also apparent, however, that further refinement is required; further and fuller attention to social-status factors comes immediately to mind.

Languages and Communities: The Work of Heinz Kloss

Kloss (1966) discusses factors that are favorable, unfavorable, or ambivalent in settings of possible cultural and linguistic maintenance or shift. As Clyne (2003) implies, the last of these three sets is perhaps the most interesting. Greater absolute numbers and higher levels of education can, for example, be seen as strengths – but they may also lead to greater contact with the surrounding culture, with the familiar implication for the “smaller” community. Another factor that can, according to circumstance, either promote or retard the fortunes of such groups is the degree of linguistic distance separating them from the “larger” variety: if this distance is small, it may be more difficult to maintain a minority language or culture; on the other hand, linguistic proximity will mean that minority-group members can move in the larger milieu more effortlessly, and (Clyne notes) may thus be freer to attend to their own cultural and linguistic situation. The attitudes of the members of the “larger” group to those of the “smaller” may also be classed under the “ambivalent” heading. Negative sentiments may provoke renewed defensive activity on the part of culturally threatened communities, but, equally, they may promote assimilation. More favorable attitudes may reinforce maintenance or revival efforts in some settings, while in others they may sap them by inducing a false sense of confidence (or perhaps, as Clyne suggests, apathy).

A little later, Kloss (1967) presented ten variables of importance in distinguishing among multilingual communities. These include the legal status of languages, their unofficial status or prestige, the degree of bi-or multilingualism among different sectors or classes of the community, the types of bilingualism (“natural,” “voluntary,” or “decreed”), the degree of distance between and among the various languages spoken, and the “indigenousness” of speech communities.

Language Ecology: The Work of Einar Haugen

In the introduction to his model, Einar Haugen makes the following useful observations:

most language descriptions are prefaced by a brief and perfunctory statement concerning the number and location of its speakers and something of their history. Rarely does such a description really tell the reader what he ought to know about the social status and function of the language in question. Linguists have generally been too eager to get on with the phonology, grammar, and lexicon to pay more than superficial attention to what I would like to call the “ecology of language.”

(Haugen 1972: 325)

To this we might add that those interested in contact situations who are not linguists – but who are, rather, educationalists, sociologists, psychologists, and others – have also generally failed to give more than superficial attention to ecological variables. More specifically, typical descriptions refer to only a fraction of the potentially important variables, possibly to those which seem most salient for a given setting. Not attending to other variables – ones that may be less obvious, or less immediately germane – can lead to inaccuracies, as well as contributing to a lessening of inter-situation comparability and generalization.

In his 1972 popularization of the ecology-of-language approach, Haugen naturally emphasized the study of interactions between a language and its environment. Specifically, he posed ten questions that he felt should be answered for any given language: these have the effect of directing our attention to such factors as formal linguistic classifications, the varieties, users, and uses of given languages, degrees of standardization, written traditions, and levels of official and unofficial support. All of these are, in fact, aspects of the broader ecological niches occupied by languages and language communities. The strength of Haugen’s model is that it presents a framework within which language contexts can be considered; indeed, its very existence provides a stimulus to examine vital ecological features. The model is very general, however, in that each question implies a host of sub-questions; the fact that these are not specifically laid out leads to a loss of precision and possibly, therefore, to a decreased generalizability. As well, Haugen ignores some important ecological variables altogether. There is no historical dimension; educational, religious, and other dimensions are merely implied; a geographical dimension is absent; and so on.

Haugen’s approach also refers quite generally to matters of language status and intimacy, where the former signifies the power a language possesses through the social standing of its speakers, and the latter the associations with community solidarity, friendship, and bonding. This has interesting overlaps with Lambert’s (1967) psycho-social categories of language attitudes (“competence,” “personal integrity,” and “social attractiveness”). While the first of these may be thought of as a status dimension (in Haugen’s terms), the second and third clearly have intimacy and solidarity overtones; see also the many further refinements in the categorization of language attitudes (Edwards 1994). In a later publication, where he again stresses the ecology-of-language construct, Haugen (1981) goes on to discuss the language market: languages (and, we might add, other cultural “markers”) in contact may be seen as commodities, surviving only so long as they find customers.1

A final point to be made here – it is not a criticism of Haugen’s model, at least not a direct one – is that his outline has not been very much taken up by other researchers. Haarmann (1986) rightly points out that scholars had been conducting “ecological” investigations before Haugen gave us his framework (and since, too, of course). But given Haugen’s aim of more formally encapsulating the necessary requirements for an ecological understanding, it is surprising that we have not seen direct acknowledgment. (Two important books on the sociology of language – by Fasold [1984] and Wardhaugh [1986] – that were published shortly after Haugen’s model appeared did not mention the ecology of language at all.)

Ethnolinguistic Vitality: The Work of Howard Giles

With their conception of ethnolinguistic vitality, Giles and his research associates have given us a model of particular psychological import. Thus, Giles et al. (1977) proposed a three-part model in which “status,” “demographic,” and “institutional-support” factors were seen to contribute to the survivability of an ethnolinguistic collectivity. Each factor comprises a number of variables: status includes economic, social, and linguistic attributes; demography reflects population distributions, concentrations, and so on; and institutional support includes formal and informal facets like the media, education, government, and religion. The specifically psychological aspects come with the extension of the notion of ethnolinguistic vitality to perceived or “subjective” vitality. Bourhis et al. (1981) argued that group members’ perceptions of vitality may not always agree with objective assessment, and that perceptions may prove more important than such assessment in determining group and individual behavior (see also Foster, above). In fact, given everything that psychology has taught us over the years, the point could be stated much more strongly, since perceptions are the basis – indeed, the only possible basis – for all human behavior.

In their article, Bourhis et al. present a “subjective-vitality questionnaire,” the twenty-two items of which relate directly to the original three-factor model. Subjects were required to assess status, demographic, and institutional factors, both for their own group and for a salient outgroup, the result being a subjective estimate of vitality. The first administration of the questionnaire targeted Australian citizens of British and Greek descent in Melbourne. They were asked (among other things) to comment on (a) the prestige of Greek and English in Melbourne, (b) the degree of pride that those of Greek and British descent have in their cultural history and achievements, (c) the extent of intra-group marriage in each community, (d) the level of teaching in each language in Melbourne schools, and (e) the political power possessed by each group. Another question (f) asked respondents to estimate birth rates in each of the two communities. It can be seen that (a) and (b) reflect perceived status, (c) and (f) demographic factors, and (d) and (e) institutional support.

Since this initial study, the subjective-vitality questionnaire has been used by researchers in a variety of cultural contexts. The model itself has been widely referenced, and has proved to have considerable heuristic value; among the more recent commentaries and expansions are those of Russell (2000) and Lewis (2000). In general, the strength of the approach lies in the provision of important insights into psychological features of ethnolinguistic situations. Nonetheless, it shares some difficulties with the Haugen and Haarmann models. Most particularly, the areas subsumed under each factor are too general, and some important areas are neglected altogether. It is true that, in the original “objective” model (Giles et al. 1977), the accompanying discussion gave useful details on each area; as well, the authors admit that their analysis is not an exhaustive one. Nevertheless, they also pointed out that their three-factor scheme can meaningfully group linguistic minorities, and the subsequent translation into the “subjective” form might be seen to have prematurely solidified the factors in their twenty-two-item format.

In the subjective format, at least, areas including the historical, economic, religious, political, and educational are assessed with only one question each; and, as the sample questions reproduced above show, the level of assessment is extremely rudimentary. It follows from this that some vital matters are left untreated. For example, to assess the educational aspect solely with a question about the extent of language teaching at school is to omit consideration of the following: teaching about languages, teaching through languages, dialect treatment at school, multicultural policies and practices at school, school as an agent of language renewal or promotion, school as a force in the continuity of ethnolinguistic identity, and so on.

Perhaps the most important point about any typology is that it should be comprehensive. Without this quality, it may have plausibility and face validity, but it will necessarily be limited in scope and may thus lead to what Husband and Saifullah Khan (1982) have seen as attractive but illusory conceptions. It is not clear where the makers of the ethnolinguistic-vitality taxonomy obtained their variables, in any systematic sense, and no acknowledgment is made of the other typologists whose work I have mentioned here. While one can fully recognize the scholarship behind the vitality model, one is also drawn to the conclusion that, like other outlines, it suffers from a lack of both breadth and specificity.

Ecology Revisited: The Work of Harald Haarmann

Among the most methodical and systematic attempts to enlarge upon the language-ecology motif is that of Haarmann (most conveniently summarized in his 1986 book). By dividing the broad ecological dimension into seven important components – demographic, sociological, political, cultural, psychological, linguistic, and “interactional” – Haarmann directs our attention to matters of group size, status, geographical location, political clout, history, and identity, as well to specific linguistic matters (including language varieties, uses, functions, and domains). He provides considerable detail about many of the most relevant variables, supplies numerous examples, and presents a profile of a hypothetical speech community with a strong tendency to language shift.

As with Haugen’s earlier model, then, this seven-category scheme provides an outline for the study of situations of language and cultural contact. While it is somewhat more detailed than its predecessor, Haarmann’s model remains open to the same sort of criticisms. Even though the categories are subdivided in useful ways, the level of specificity still leaves something to be desired. For example, in the third (ethnopolitical) category, group–state relations and the institutional status of languages each require further breakdown, as do the organizational promotion of group interests and group attitudes (in the ethnocultural and ethnopsychological categories, respectively). As well, there is considerable overlap among the categories (particularly those involving sociological, political, and cultural variables). Geographical and historical components are again lacking, and some of the variables that are present do not encompass the necessary range. For example, Haarmann notes that extreme language-shift conditions may have the following consequences: a community identity based mainly upon tendencies towards acculturation, speakers’ rejection of the mother tongue as an identity component – and therefore a lack of will to maintain it – and increasing praise for prestige of the language towards which shift is occurring. These assertions are not necessarily inaccurate, but all are open to considerable further investigation, and psychological study has revealed that, in each case, more than a simple “either-or” dichotomy will virtually always apply.

Of course, Haarmann (and others) could respond to some of the critical points I have raised by noting that their models in no way restrict the sorts of amplifications and expansions mentioned here. Nevertheless, the fact remains that these points of detail are not explicitly presented, and I take this to be a failing in frameworks that are meant to facilitate comparability across situations. (It will be seen, below, that this failing is one that I have not completely avoided in my own typological effort.)

Some Further Insights

Beyond the work just mentioned, there have been several other important typological undertakings. For instance, the proceedings of a 1977 Quebec conference on linguistic minorities (Colloque sur les Minorités Linguistiques, 1978) was entirely devoted to typological matters. It began with a useful paper in which Héraud introduced a baker’s dozen of minority contexts. Following this, Pernthaler, Plastre, Mackey, and Brazeau presented taxonomic frameworks dealing with legal variations, public-service responses, educational treatments, and the use of minority languages in the realm of private enterprise, respectively. Virtually all of the points raised in this collection can be isolated in most of the other schemes reported on here, and certainly in my own. But its 300 pages represent one of the most concentrated efforts under one scholarly roof, and still repay close attention.

A UNESCO working party (2003) provided a list of nine factors bearing upon levels of linguistic (and, we might add here, cultural) endangerment.2 Among these were the number of speakers, the maintenance or loss of important domains of use, official and unofficial attitudes, and intergenerational language transmission. Lewis (2005) then applied their observations in 100 settings (“a small but broad sample of the world’s languages,” he notes: 5), and some of his findings are worth reproducing here. For instance, he states at the outset that data were missing for a very large number of informational cells – particularly for African language communities which, he notes, are “seriously under-documented” (24). He also draws attention to the fact that items in the UNESCO listing are often ill defined, or overly simplistic in their scope, or both. He concludes that the framework is usefully suggestive but that further elaborations are clearly needed. The upshot, then, is one that links the UNESCO suggestion to other approaches: existing typologies are insufficiently developed, and the data upon which good ones would have to rely are not always available.

Fishman et al. (1985) touched upon most of the important factors bearing upon cultural and linguistic contact in America. Of special interest is their attention to the institutional resources – particularly those within minority groups – whose influence can be so important here. The details here are of great value, although the overall impact is lessened somewhat by the essentially quantitative approach taken. That is, as Clyne (2003: 58) notes, the assumption of a “linear relationship between the number of institutions and language maintenance” is dubious. He goes on to write that some “language maintenance institutions may be dependent on language maintenance patterns themselves.” We can surely assume that the relationship is often a circularly reinforcing one.

Smolicz and his colleagues outlined a model that highlights cultural “core values” (see Smolicz 1992; Smolicz et al. 2001). Drawing upon the Australian experience, they argue that ethnic groups vary in the importance they attach to different cultural “markers.” Italians, for example, are said to emphasize family over language, Jews stress religion and a sense of history, the Irish core is Catholicism, and the Poles stress language. The upshot is that since, for some, language is not so central to identity, an explanation for differences in linguistic shift among minority groups might be possible.

The value of the “core” concept, however, may be rather more superficial than it first seems. There are undoubtedly differences in cultural emphases among groups; the question is why they should exist. Smolicz notes that Poles hung on to their language despite linguistic persecution – indeed, he states that attempts to extirpate Polish actually reinforced the language as a symbol of group survival. But how, then, did English prejudice and oppression contribute so significantly to the virtual disappearance of the Irish language? Why did it not strengthen, too, in the face of opposition? Smolicz writes that the Irish, “bereft of their ancestral tongue” (1981: 110), found refuge for their identity in Catholicism. This is altogether too neat, however. The concept of core values may or may not be of some explanatory use, but it certainly requires considerable historical sensitivity. We should be careful, in particular, not to confuse core values with surviving aspects of ethnicity. On the other hand, perhaps surviving features are, in fact, the core values – or are easily perceived as such, in any event. There is a looming circularity to be avoided here.

My general suspicion is that the concept of a core value says more about historical changes in the face of changing, and different, environments than it does about central differences across ethnic groups per se. After all, what group has not stressed all the elements noted by Smolicz (language, religion, family, ancestry, and so on)? What group would not maintain all its “original” elements if this were possible without social cost? These identity features typically continue to be stressed for some time after groups come to occupy a minority position in a larger society. The familiar decline in aspects of ethnicity that then so often occurs – and, more pointedly, the variations in the “retreat” among different ethnic “markers” – can perhaps be more accurately explained in terms of some public–private ethnic-marker distinction than on the basis of “core values.”

Finally here, we should note that – apart from providing extremely useful critical comments on a number of taxonomic models (including those of Kloss, Edwards, Giles, Fishman, and Smolicz) – Clyne (2003) has suggested some expansions of his own. For example, after presenting a summary of Kloss’s “ambivalent” factors, he points out that religious variables and the circumstances existing in the homeland that (immigrant) minorities have left can be double-edged swords when it comes to cultural and linguistic maintenance and shift. Thus, in some religious traditions, central spiritual values are associated with a specific language: this obviously provides powerful reinforcement for language maintenance. In other denominational settings, however, languages are considered in more instrumental lights, with the result that language shift is not – from the religious point of view, at least – seen as quite so pivotal a matter. As for homeland circumstances, it seems clear enough that those who have fled an oppressive state may have weaker attachments to its language and culture. On the other hand, they may become zealous in the defense and promotion of their cultural inheritance if they feel it has been co-opted or corrupted by the oppressors.

A New Approach: Introductory Remarks

As I have already implied, the researchers whose work I have briefly touched upon here are not the only ones who have interested themselves in typological exercises. Indeed, my explorations have revealed more than thirty other contributions to the area within the last three decades. None of these, however, has had the scope of those I have dealt with above, where the discussion has – I hope – shown what fruitful work has already been done. Haugen and Haarmann, in particular, have made admirable contributions in an ecology-of-language framework, and the subjective ethnolinguistic-vitality treatment of Giles and his co-workers has provided at least the beginnings of a psychological perspective. I believe, however, that we can move on a bit further here. While my own contribution is still a work in progress, it is clear enough in principle what must be done.

First, some drawing up of relevant factors and variables is required. This should reflect the breadth inherent in the area, but it should also assume as specific a form as possible. One or two general descriptive statements or questions about the religious aspects of minority-group dynamics, for example, will be much less useful than a number of more pointed ones. With reference again to the observation by Ferguson that I reproduced at the beginning of this chapter, it would seem that some enhanced specificity at this stage of development could prove useful in and of itself. There are further possibilities, too, however. An obvious one would involve an attempt to provide relative weightings for variables – relating factors to cultural and language shift or maintenance outcomes via regression analyses, for example. As well, providing that initial inputs were sufficiently broadly based, factor-analytic reduction techniques could create meaningful and heuristic infrastructures. Besides these sorts of formal manipulations, more common-sense adjustments will undoubtedly be required. It will surely become clear, for example, that certain variables are more important for some groups than for others. Relatedly, provision must always be made for the interactions existing among variables.

Most important, perhaps, is the necessity for informed probing into the meaning possessed by given variables in given contexts. It is to be expected that many groups will appear similar at superficial levels, but it is also predictable that deeper analysis will often reveal important differences. If, for instance, two cultural-contact situations revealed male–female differences in attitudes and practices, we would presumably want to know something of the social dynamics of the two communities in order to appreciate the degree of significance reflected in these differences. As well, if we were to use a typological model as an instrument to assess subjective feelings – and there is no reason why the same outline of variables could not be used for both objective and subjective evaluations – then probing for meaning would become vitally important.

The Dimensions of a Comprehensive Typological Model

My initial consideration of variables that have been regularly and repeatedly stressed in the literature suggested three very rough and basic categories: speaker, language, and setting. These are not, of course, watertight and mutually exclusive compartments, but they may serve as logically important benchmarks. For example, it is possible to list all relevant variables under one or more of the three headings, and they do reflect the spirit of an ecological enquiry – that is, one that emphasizes the interactions among cultures, languages and broader social environments.

Any list of speaker variables should attend to: age; sex; socioeconomic, occupational and educational status; numbers and concentrations of regular and “irregular” speakers; type of speaker community (e.g. dominant or subordinate); number of monolinguals and bilinguals (with due regard to types and strengths of bilingualism); degree of desire to shift (assessing motivations like communicative efficiency, social mobility, economic advancement, and so on); language attitudes (a large category, including such elements as the romanticism of the language movement, differences between “ordinary” speakers and group “leaders” in levels of language activism, and feelings of linguistic insecurity).

Under the language rubric, important matters include: the degree of linguistic borrowing, simplification, and so on; the stability or instability of bilingualism, and whether it tends to be temporary or permanent; the nature of literary traditions; the oral or written nature of the variety; the breadth of the language (is it, for instance, a medium of “wider communication”?); the degree of standardization and modernization (and of language planning in general); the amount and salience of internal dialectal variation; symbolic and identity-bearing characteristics (that may or may not co-exist with more ordinary communicative functions); the nature of any competing varieties, especially those having lingua franca status; the particular associations with other important social phenomena (religion, for example).

Setting variables will include the following: geographic classifications; degree and type of transmission from one generation to the next; the rural-urban nature of the variety (rurality often provides a heartland but at the same time may have connotations of poverty and lack of sophistication; urbanity is often desired as part of social mobility and is often associated with shift – but can also support the heart of intellectual revival movements); the nature and stability of immigration and emigration; state policies regarding the language and its users; institutional support from education, the media, and so on.

We should also consider, by way of cross-perspective, a categorization of different disciplinary perspectives. The following immediately suggest themselves as germane: demography, geography, economics, sociology, linguistics, psychology, history, politics–law–government, education, religion, and the media. Again, these are hardly mutually exclusive categories, nor do I suppose that these eleven cover all the necessary ground. In the interests of brevity, I provide here – in four groupings – only a few of the relevant matters that present themselves under each of these disciplinary headings; where possible, I have taken the opportunity to draw attention to some less frequently discussed matters.

The extraction of information from basic statistics is more complicated – and more broadly valuable – than might first be supposed. Thus, in discussing “demolinguistics,” de Vries (1990: 57) indicated the usefulness of this avenue for “the study of second-language acquisition, language maintenance and shift pertaining to linguistic minorities … assessing the relative contributions of fertility, mortality, nuptiality, migration and language shift to the survival or decline of minority language communities.” A geographical framework has, of course, already been outlined in this chapter. There are relevant geographical variables, however, beyond those revealed or suggested in Table 3.1. More attention could be given, for instance, to the physical avenues of transportation and communication available to a language community: as was the case in Gaelic-speaking Cape Breton Island, the road desired for mobility may also be the road of cultural and linguistic change. While not wishing to argue for a simplistic “reductionism,” it is difficult to deny that, in terms of economics, mundane facts have a great deal to do with minority-group viability. This is not, of course, a popular line among many of the more romantically inclined apologists for language and cultural maintenance and, perhaps for that reason, the point has not received due attention.

A sociological perspective might include attention to marriage patterns, often of considerable importance in the life of minority groups: majority–minority intermarriage is often detrimental to minority-language survival and transmission. Yet, two studies of ethnicity in Nova Scotia (Edwards and Doucette 1987; Edwards and MacLellan 1989) revealed that even students who clearly see themselves as ethnic-group members – and who are, of course, of more or less marriageable age themselves – place within-group marriage at the bottom of a list of factors seen to be important for identity maintenance and continuity. A related sociological factor of great importance is the degree of what Breton (1964) usefully termed “institutional completeness.” The more self-sufficient a community is, the greater the likelihood of linguistic and cultural maintenance. A matter not sufficiently discussed under the heading of linguistics is the degree of dialectal variation found within a given minority-language community. In Nordfriesland, for example, in an area of some 800 square miles, there are five languages in regular use. One of these, Frisian, is divided into ten major dialects, not all of which are mutually intelligible, among a population of only 10,000. It is not difficult to understand that coming to grips with such internal variation would be vital in any investigation of the setting. A major psychological thrust has always been the study of attitudes. With regard to language and culture, important topics here include differences between communicative and symbolic facets of language, and between group “spokesmen” and more “ordinary” constituents. We also need more information than we typically receive about the perceptions of majority-group members. If, for instance, they report themselves as broadly favorable towards minority-group continuity, do their attitudes and actions cover active promotion, or do they suggest a more passive goodwill towards diversity? Under what circumstances, if any, can goodwill be translated into something more dynamic and positive for minority-group viability?

An historical dimension is essential for a meaningful study of cultural-contact situations. In terms of language specifically, historians have generally not acquitted themselves very well. Thus, Seton-Watson (1981: 2) wrote that “the history of language … forms a very important part of social history, and one which seems to me to be relatively neglected by most historians.” At the same time, most students of language have paid little attention to history. Not only has the historical perspective typically been given short shrift in research in the sociology of language, examination of the historical record is (as I’ve mentioned) sometimes downplayed for not producing “data” of the sort most familiar to researchers in sociology or psychology. The myopia is obvious. One of the most interesting political aspects of minority–majority contexts is the potential clash between group and individual rights. The “sign laws” in Quebec, for example, were clearly a restriction of the rights of individual Anglophones (in this case, to display commercial signs in English) in the cause of support of Francophone language and culture in the province. Efforts were considered necessary, that is to say, at the level of a group perceived to be under cultural and linguistic threat. In general terms, difficulties can be expected to arise in such situations, particularly in societies in which rights have traditionally been taken to inhere in the individual person rather than in collectivities.

A very important factor under the educational heading involves the type and extent of school support for minority languages. Only fairly fine-grained investigation will reveal what really goes on in classrooms, as opposed to what official policy dictates should go on. Only careful study will tell us if the fifteen hours given weekly to a minority language in context “A” is in any way comparable to the same time allotment given in context “B.” It is sometimes the case that a strong association exists between a language and religion; in the Irish situation, for example, much was made by revivalists of this connection. A related matter worthy of more study is the question of whether and/or when secularization contributes to language shift. A useful perspective on the media is to view them as double-edged swords. On the one hand, it can be argued that the presence of minority-group language and culture, particularly on television, is of great importance for group solidarity and legitimacy; indeed, it has been suggested that television has become a new language domain in its own right. On the other hand, the pervasiveness of satellite-transmitted television, coupled with the overwhelmingly American (or Americanized) content, may create real difficulties for cultural and linguistic maintenance efforts.

A simple cross-tabulation of speaker, language and setting variables with the disciplinary perspectives just noted gives rise to the sort of framework depicted in Table 3.2. It is quite easy to think of the sorts of questions suggested by each of the thirty-three “cells,” or points of intersection, and a list follows here. Of course, these questions are not anywhere near specific enough, in themselves, to comprise a complete or usefully applicable typology – they are merely points of departure. It is also immediately apparent that, in some instances, questions could plausibly fit in more than one cell. Readers are reminded that all this is meant only as an approximation, in the expectation that further work will result in changes and refinements. With these provisos, here is a list of questions, one for each cell, keyed by number to the cells in Table 3.2:

1. Numbers and concentrations of speakers?

2. Extent of the language (see also geography)?

3. Rural–urban nature of setting?

4–6. See geographic outline (Table 3.1)

7. Economic health of speaker group?

8. Association between language(s) and economic success/mobility?

9. Economic health of the region?

10. Socioeconomic status of speakers?

11. Degree and type of language transmission?

12. Nature of previous/current maintenance or revival efforts?

13. Linguistic capabilities of speakers?

14. Degree of language standardization?

15. Nature of in-and out-migration?

16. Language attitudes of speakers?

17. Aspects of the language-identity relationship?

18. Attitudes of majority group towards minority?

19. History and background of the group?

20. History of the language?

21. History of the area in which group now lives?

22. Rights and recognition of speakers?

23. Degree and extent of official recognition of language?

24. Degree of autonomy or “special status” of the area?

25. Speakers’ attitudes and involvement regarding education?

26. Type of school support for language?

27. State of education in the area?

28. Religion of speakers?

29. Type and strength of association between language and religion?

30. Importance of religion in the area?

31. Group representation in media?

32. Language representation in media?

33. General public awareness of area?

Table 3.2 A framework for approaching situations of cultural and linguistic contact

Source: Edwards 1992.

Concluding Comments

The typological approach that I suggest here was sketched in several earlier publications (see Edwards 1991, 1992), which means that other scholars have had a chance to consider it. Grenoble and Whaley (1998) draw centrally upon the model, for instance, and cite both strengths and weaknesses of it. They note that it usefully distinguishes between the speech community in question and the surrounding context, while at the same time emphasizing the intertwining of variables at all levels of specificity. On the other hand, they (rightly) reveal the need for further model elaboration – pointing out that some existing terms (“region” and “area,” as mentioned in questions 9 and 21, for instance) are inadequately defined, that variables might profitably be placed in some hierarchical order, and that more focused attention upon literacy is required. (This is not unrelated to Clyne’s [2003] observation that my model requires greater descriptive clarity. He does, however, refer favorably to the contextualization of variables that is, indeed, a central thrust of the model – something, he notes, that “could be considered more in the methodology of future studies” [244].)

In her study of language shift and revival among Quichua speakers in Ecuador, King (2001) briefly discusses the model, citing it along with Fishman’s “Graded Intergenerational Dislocation Scale” (1991) and a three-part framework suggested by Hyltenstam and Stroud (1996). The latter emphasizes the social conditions that surround languages and that dictate their fortunes: the authors focus upon variables having to do with communities at both social and individual levels, and with the sociology of majority–minority interaction. The approach is thus broadly similar in intent to my own, but it does not highlight matters at quite the same levels of specificity. Fishman’s approach is much less useful, in that his eight-point scale of obstacles to revival represents only a formalization of the familiar challenges faced by “small” languages. It is – to use his own comparison – a sort of Richter Scale of endangerment. As well, since Fishman’s intent is to outline the stages by which minority-language shift can be reversed, the model is more of a hortatory action plan than a purely descriptive framework. As Clyne (2003: 64) observes, the steps towards the “reversal of shift” seem not to coincide very well with the desired life trajectories of many immigrant minority populations: “many of the measures suggested by Fishman would tend to detract from [their] socioeconomic mobility and would therefore not appeal to most.”

In their studies of Bashkir, Altai, and Kazakh speakers in the Russian republics of Bashkortostan and Altai, Ya![]() mur and Kroon (2003, 2006) have employed my framework in conjunction with the ethnolinguistic-vitality approach of Giles and his colleagues. Paulston et al. (2007) have referred to it in their examination of “extrinsic” linguistic minorities – that is, groups who once belonged to a majority population in a neighboring country (Russians in Latvia being the clearest case in point). “At the stroke of a pen,” the authors write (2007: 386), members of the dominant ruling power can become minorities in a newly independent state. Extra and Gorter (2008) discuss my approach in the introduction to their own framework for regional minority languages in Europe. They opt “for a simple typology” (26) and their framework has five categories: languages spoken in only one member state of the European Union; those spoken in more than one – either unofficial in each or official in some; those three varieties (Lëtzebuergesch, Irish, and Maltese) that are “small” but yet have official status; and non-territorial languages (notably Romani and Yiddish). Tsunoda (2006) uses the model as the scaffolding for his chapter on endangered languages (“we shall adopt Edwards’ … typology, which sets up eleven groups according to which various factors may be classified” [49]). In so doing, he reminds us that typologies are a variety of ecological investigation. (Unfortunately, the great potential value of Tsunoda’s monograph – as a comprehensive survey of endangered languages – is curtailed by a rambling and often indigestible presentation. As Mühlhäusler [2007: 105] notes, the confusion and lack of coherence here are particularly disappointing in a volume meant to be “a textbook or a guide for practitioners.”)

mur and Kroon (2003, 2006) have employed my framework in conjunction with the ethnolinguistic-vitality approach of Giles and his colleagues. Paulston et al. (2007) have referred to it in their examination of “extrinsic” linguistic minorities – that is, groups who once belonged to a majority population in a neighboring country (Russians in Latvia being the clearest case in point). “At the stroke of a pen,” the authors write (2007: 386), members of the dominant ruling power can become minorities in a newly independent state. Extra and Gorter (2008) discuss my approach in the introduction to their own framework for regional minority languages in Europe. They opt “for a simple typology” (26) and their framework has five categories: languages spoken in only one member state of the European Union; those spoken in more than one – either unofficial in each or official in some; those three varieties (Lëtzebuergesch, Irish, and Maltese) that are “small” but yet have official status; and non-territorial languages (notably Romani and Yiddish). Tsunoda (2006) uses the model as the scaffolding for his chapter on endangered languages (“we shall adopt Edwards’ … typology, which sets up eleven groups according to which various factors may be classified” [49]). In so doing, he reminds us that typologies are a variety of ecological investigation. (Unfortunately, the great potential value of Tsunoda’s monograph – as a comprehensive survey of endangered languages – is curtailed by a rambling and often indigestible presentation. As Mühlhäusler [2007: 105] notes, the confusion and lack of coherence here are particularly disappointing in a volume meant to be “a textbook or a guide for practitioners.”)

Vail (2006) has recently employed the model in his assessment of Northern Khmer. He notes that cultural and social anthropology are “curious omissions from [my] otherwise comprehensive list” (144). He is right, of course – and there are no doubt many other fine-grained perspectives that could reasonably be included. I did think, however, that the sociological and linguistic perspectives would be sufficient, since their application would necessarily have anthropology-of-culture and anthropology-of-language. Overall, Vail refers to my typology as “the most robust model” (2006: 140) of both macro-and micro-level approaches to the ecology of endangered languages. These are kind words. Clearly, however, much more work needs to be done before a really useful typology can emerge from these beginning sketches. Nonetheless, based upon the work of my predecessors – and recalling specifically the words of Haugen and Ferguson – the exercise appears eminently worthwhile. Even a thoroughgoing multivariate checklist would be of service, and a comprehensive typology could be a useful tool for description and comparison, could lead to more complete conceptualizations of minority-language situations, could be a heuristic for further and more systematic investigations, and could perhaps permit predictions to be made concerning shift and maintenance outcomes.

NOTES

1 Haugen (1983) has also provided an outline – a taxonomy of sorts – of the features involved in language-planning exercises. His model has four main features: selection, codification, implementation, and elaboration. The selection and implementation of a given variety are essentially extra-linguistic, social matters; codification and elaboration, on the other hand, deal directly with the language itself. Haarmann (1990) has also treated this so-called “status” and “corpus” planning. Haugen’s was one of the first models of language planning, now an area with a very large literature of its own. Taxonomic arrangements and categorizations – whether formally articulated or not – have remained at its core. After all, the very notion of “planning” necessarily involves formalizations of one sort or another. This is clearly evident in the masterful overview of the field provided by Kaplan and Baldauf (1997).

2 In its famous publication advocating the mother tongue as the best medium for young schoolchildren, UNESCO (1953) also provided a list of language types, not unlike the later frameworks of Stewart, Ferguson, and others.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, Alan. 1980. The problem of minority languages: Canadian and European contexts. Paper presented at the First International Conference on Minority Languages, Glasgow.

Anderson, Alan. 1981. The problem of minority languages: Reflections on the Glasgow conference. Language Problems and Language Planning 5, 291–303.

Bourhis, Richard, Howard Giles, and Doreen Rosenthal. 1981. Notes on the construction of a “Subjective Vitality Questionnaire” for ethnolinguistic groups. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 2, 145–55.

Brazeau, Jacques. 1978. Typologie sur l’emploi des langues dans l’entreprise privée. In Colloque sur les Minorités Linguistiques (ed.). Minorités linguistiques et interventions: essai de typologie. Quebec: Presses de l’Université Laval. 259–77.

Breton, Raymond. 1964. Institutional completeness of ethnic communities and the personal relations of immigrants. American Journal of Sociology 70, 193–205.

Clyne, Michael. 2003. Dynamics of Language Contact. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Colloque sur les Minorités Linguistiques (ed.). 1978. Minorités linguistiques et interventions: essai de typologie. Quebec: Presses de l’Université Laval.

De Vries, John. 1990. On coming to our census: A layman’s guide to demolinguistics. In D. Gorter, J. F. Hoekstra, L. G. Jansma, and J. Ytsma (eds.). Fourth International Conference on Minority Languages. Volume 1: General Papers. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. 57–76.

Edwards, John. 1985. Language, Society and Identity. Oxford: Blackwell.

Edwards, John. 1991. Socio-educational issues concerning indigenous minority languages: Terminology and status. In Jantsje Sikma and Durk Gorter (eds.). European Lesser Used Languages in Primary Education. Ljouwert/Leeuwarden: Fryske Akademy/Mercator. 207–26.

Edwards, John. 1992. Sociopolitical aspects of language maintenance and loss: Towards a typology of minority language situations. In Willem Fase, Koen Jaspaert, and Sjaak Kroon (eds.). Maintenance and Loss of Minority Languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 37–54.

Edwards, John. 1994. Multilingualism. London: Routledge.

Edwards, John. 2010. Minority Languages and Group Identity. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Edwards, John and Lori Doucette. 1987. Ethnic salience, identity and symbolic ethnicity. Canadian Ethnic Studies 19, 52–62.

Edwards, John and Barbara MacLellan. 1989. A sociolinguistic profile of Inverness County, Cape Breton. Unpublished paper.

Extra, Guus and Durk Gorter. 2008. The constellation of languages in Europe: An inclusive approach. In Guus Extra and Durk Gorter (eds.). Multilingual Europe: Facts and Policies. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 3–60.

Fasold, Ralph. 1984. The Sociolinguistics of Society. Oxford: Blackwell.

Ferguson, Charles. 1962. The language factor in national development. In Frank Rice (ed.). Study of the Role of Second Languages in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics. 8–14.

Ferguson, Charles. 1966. National sociolinguistic profile formulas. In William Bright (ed.). Sociolinguistics. The Hague: Mouton. 309–15.

Ferguson, Charles. 1991. Diglossia revisited. Southwest Journal of Linguistics 10, 214–34.

Fishman, Joshua. 1991. Reversing Language Shift. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Fishman, Joshua, Michael Gertner, Esther Lowy, and William Milán. 1985. The Rise and Fall of the Ethnic Revival. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Foster, Charles. 1980. Agenda for research. In Charles Foster (ed.). Nations without a State. New York: Praeger. 209–10.

Garner, Mark. 2004. Language: An Ecological View. Bern: Peter Lang.

Giles, Howard, Richard Bourhis, and Donald Taylor. 1977. Towards a theory of language in ethnic group relations. In Howard Giles (ed.). Language, Ethnicity and Intergroup Relations. London: Academic Press. 307–48.

Grenoble, Lenore and Lindsay Whaley. 1998. Toward a typology of language endangerment. In Lenore Grenoble and Lindsay Whaley (eds.). Endangered Languages: Current Issues and Future Prospects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 22–54.

Haarmann, Harald. 1986. Language in Ethnicity: A View of Basic Ecological Relations. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Haarmann, Harald. 1990. Language planning in the light of a general theory of language: A methodological framework. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 86, 103–26.

Haugen, Einar. 1972. The ecology of language. In Anwar Dil (ed.). The Ecology of Language: Essays by Einar Haugen. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. 324–39.

Haugen, Einar. 1981. Language fragmentation in Scandinavia: Revolt of the minorities. In Einar Haugen, J. Derrick McClure, and Derick Thomson (eds.). Minority Languages Today. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. 100–19.

Haugen, Einar. 1983. The implementation of corpus planning: Theory and practice. In Juan Cobarrubias and Joshua Fishman (eds.). Progress in Language Planning. Berlin: Mouton. 269–89.

Héraud, Guy. 1978. Notion de minorité linguistique. In Colloque sur les Minorités Linguistiques (ed.). Minorités linguistiques et interventions: essai de typologie. Quebec: Presses de l’Université Laval. 15–38.

Husband, Charles and Verity Saifullah Khan. 1982. The viability of ethnolinguistic vitality: Some creative doubts. Joumal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 3, 193–205.

Hyltenstam, Kenneth and Christopher Stroud. 1996. Language maintenance. In Hans Goebl, Peter Nelde, Zden![]() k Starý, and Wolfgang Wölck (eds.). Kontaktlinguistik: Ein internationales Handbuch zeitgenössischer Forschung. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. 567–78.

k Starý, and Wolfgang Wölck (eds.). Kontaktlinguistik: Ein internationales Handbuch zeitgenössischer Forschung. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. 567–78.

Kaplan, Robert and Richard Baldauf. 1997. Language Planning: From Practice to Theory. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

King, Kendall. 2001. Language Revitalization Processes and Prospects: Quichua in the Ecuadorian Andes. Clevedon, UK Multilingual Matters.

Kloss, Heinz. 1966. German American language maintenance efforts. In Joshua Fishman, Vladimir Nahirny, John Hofman, and Robert Hayden (eds.). Language Loyalty in the United States. The Hague: Mouton. 206–52.

Kloss, Heinz. 1967. Types of multilingual communities: A discussion of ten variables. In Stanley Lieberson (ed.). Explorations in Sociolinguistics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 7–17.

Kloss, Heinz. 1968. Notes concerning a language-nation typology. In Joshua Fishman, Charles Ferguson, and Jyotirindra Das Gupta (eds.). Language Problems of Developing Nations. New York: Wiley. 69–85.

Lambert, Wallace. 1967. A social psychology of bilingualism. Journal of Social Issues 23(2), 91–109.

Lewis, M. Paul. 2000. Power and solidarity as metrics in language survey data analysis. In Gloria Kindell and M. Paul Lewis (eds.). Assessing Linguistic Vitality: Theory and Practice. Dallas, TX: Summer Institute of Linguistics. 79–102.

Lewis, M. Paul. 2005. Towards a Categorization of Endangerment of the World’s Languages. Dallas, TX: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Mackey, William. 1978. Typologie des interventions dans le domaine de l’enseignement. In Colloque sur les Minorités Linguistiques (ed.). Minorités linguistiques et interventions: essai de typologie. Quebec: Presses de l’Université Laval. 209–28.

Mühlhäusler, Peter. 2007. Review of Language Endangerment and Language Revitalization (Tasaku Tsunoda). Current Issues in Language Planning 8, 102–5.

Paulston, Christina Bratt, Szidonia Haragos, Verónica Lifrieri, and Wendy Martelle. 2007. Some thoughts on extrinsic linguistic minorities. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 28, 385–99.

Pernthaler, Peter. 1978. Modes d’action juridiques dans le domaine linguistique. In Colloque sur les Minorités Linguistiques (ed.). Minorités linguistiques et interventions: essai de typologie. Quebec: Presses de l’Université Laval. 71–83.

Plastre, Guy. 1978. Typologie des interventions dans les services publics. In Colloque sur les Minorités Linguistiques (ed.). Minorités linguistiques et interventions: essai de typologie. Quebec: Presses de l’Université Laval. 141–75.

Price, Glanville. 1973. Minority languages in Western Europe. In Meic Stephens (ed.). The Welsh Language Today. Llandysul: Gomer Press. 1–17.

Russell, Sue Harris. 2000. Towards predicting and planning for ethnolinguistic vitality: An application of grid/group analysis. In Gloria Kindell and M. Paul Lewis (eds.). Assessing Linguistic Vitality: Theory and Practice. Dallas, TX: Summer Institute of Linguistics. 103–29.

Seton-Watson, Hugh. 1981. Language and National Consciousness. London: British Academy.

Sikma, Jantsje and Durk Gorter. 1991. Inventory – a synthesis report. In Jantsje Sikma and Durk Gorter (eds.). European Lesser Used Languages in Primary Education. Ljouwert/Leeuwarden: Fryske Akademy/Mercator. 149–56.

Smolicz, Jerzy. 1981. Language as a core value of culture. In Hugo Baetens Beardsmore (ed.). Elements of Bilingual Theory. Brussels: Vrije Universiteit. 106–24.

Smolicz, Jerzy. 1992. Minority languages as core values of ethnic cultures: A study of maintenance and erosion of Polish, Welsh and Chinese languages in Australia. In Willem Fase, Koen Jaspaert, and Sjaak Kroon (eds.). Maintenance and Loss of Minority Languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 277–305.

Smolicz, Jerzy, Margaret Secombe, and Dorothy Hudson. 2001. Family collectivism and minority languages as core values of culture among ethnic groups in Australia. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 22, 152–72.

Stewart, William. 1962. An outline of linguistic typology for describing multilingualism. In Frank Rice (ed.). Study of the Role of Second Languages in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics. 15–25.

Stewart, William. 1968. A sociolinguistic typology for describing national multilingualism. In Joshua Fishman (ed.). Readings in the Sociology of Language. The Hague: Mouton. 531–45.

Tsunoda, Tasaku. 2006. Language Endangerment and Language Revitalization. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

UNESCO. 1953. The Use of Vernacular Languages in Education. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO Ad Hoc Expert Group on Endangered Languages. 2003. Language Vitality and Endangerment. Paris: UNESCO.

Vail, Peter. 2006. Can a language of a million speakers be endangered? Language shift and apathy among Northern Khmer speakers in Thailand. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 178, 135–47.

Wardhaugh, Ronald. 1986. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Blackwell.

White, Paul. 1987. Geographical aspects of minority language situations in Italy. Paper presented at the International Seminar of Geolinguistics, Staffordshire Polytechnic, Stoke-on-Trent.

Williams, Glyn. 1980. Review of Implications of the Ethnic Revival in Modern Industrialized Society (Erik Allardt). Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 1, 363–70.

Williams, Glyn. 1986. Language planning or language expropriation? Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 7, 509–18.

Williams, Glyn. 1988. Review of Third International Conference on Minority Languages: General Papers and Third International Conference on Minority Languages: Celtic Papers (both volumes: Gearóid Mac Eoin, Anders Ahlqvist, and Donncha Ó hAodha). Language, Culture and Curriculum 1, 169–78.

Ya![]() mur, Kutlay and Sjaak Kroon. 2003. Ethnolinguistic vitality perceptions and language revitalisation in Bashkortostan. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 24, 319–36.

mur, Kutlay and Sjaak Kroon. 2003. Ethnolinguistic vitality perceptions and language revitalisation in Bashkortostan. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 24, 319–36.

Ya![]() mur, Kutlay and Sjaak Kroon. 2006. Objective and subjective data on Altai and Kazakh ethnolinguistic vitality in the Russian Federation Republic of Altai. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 27, 241–58.

mur, Kutlay and Sjaak Kroon. 2006. Objective and subjective data on Altai and Kazakh ethnolinguistic vitality in the Russian Federation Republic of Altai. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 27, 241–58.