9

Silence

The role of silence in communication in linguistics is viewed not simply as an absence of noise but also as a part of communication as important as speech (Enninger 1987, 1991; Jaworski 1993, 1997; Sacks et al. 1974; Tannen and Saville-Troike 1985). Silence has been studied from perspectives as varied as semiotics, pragmatics, sociolinguistics, social psychology, and anthropology. Investigation into silence, however, poses unique challenges because silence is ambiguous and multifaceted. The problem is amplified when investigating silence in intercultural encounters as the researcher may need to consider varying assumptions and norms about use of silence across cultures. As Basso (1972: 69) puts it: “For a stranger entering an alien society, a knowledge of when not to speak may be as basic to the production of culturally acceptable behaviour as a knowledge of what to say.”

This chapter begins with an overview of the units and functions of silence to set a framework for discussion of silence in intercultural communication. Following this, major aspects of silence that have been explored in intercultural communication literature will be discussed. This will include culture-specific usages of silence reported in ethnographic studies. Findings of these studies have implications for how silence is used and interpreted in intercultural communication. In introducing the units and functions of silence, and discussing various aspects of silence in intercultural communication, this chapter proceeds from micro-level to macro-level units of discourse.

Units of Silence

Silence manifests itself in various ways. The smallest unit of silence can be found between sounds within a word, as shown in Lehtonen and Sajavaara (1985) who looked at the role of the small unit of silence when consonants are produced. Other types of micro-level units are switching pauses and inter-turn pauses (cf. Sacks et al. 1974; Walker 1985) in interaction. Sacks et al. list different types of silences in conversation from a conversation-analytical perspective. In their terms, silence within a single turn is a “pause,” and silence that occurs at a transition relevance place (TRP) where speaker change is relevant is a “gap” (1974: 715). Silence at a TRP where no one claims the floor and “the ensuing space of non-talk [which] constitutes itself as more than a gap” is described as a “lapse” or discontinuation of talk (Sacks et al. 1974: 714–15). This type of silence is similar to what Goffman (1967: 36) called a “lull.” However, as Tannen (1985: 96) points out, it is likely that “how much silence” is perceived as a “lull” varies across speech communities.

It is important to note that switching pauses and gaps are often attributed to the speaker of the turn after the pause (or gap), particularly when the turn before the gap is a question (Blimes 1998; Levinson 1983 based on Sacks et al. 1974; Walker 1985). When a gap becomes a more extensive silence, it can often be interpreted or intended as a “silent response.” Below is an example from Levinson (1983):

A: So I was wondering would you be in your office on Monday (.)

by any chance?

-> (2)

A: Probably not

(Levinson 1983: 320)

In the above exchange, speaker A interpreted the silence of two seconds after the question as a “silent response” meaning “no.” This type of silence can function as a “turn” without words. In intercultural communication, misunderstandings of this type may occur, an issue which will be discussed below.

At a macro-level, silence exists as a total withdrawal of speech in a communicative event. The unanimous silence of the participants in ritual or religious events such as in American Indian or African tribal communities (e.g. Basso 1972; Maltz 1985; Nwoye 1985) is an example. It can also be silence of one party in a communicative situation, for example students who do not talk at all in class (cf. Jaworski and Sachdev 1998; Nakane 2007).

There are some types of silences that cannot be categorized into micro-or macro-levels of discourse. One of these may be described as “hidden” silence. This refers to what remains “untold” in discourse and is often associated with power differences in social science research. Blimes (1998: 84) explains: “The notion is that any actually existing form of discourse monopolizes the field of talk and so displaces, or ‘silences,’ other possible discourse.” This type of silence does not have a recognizable “unit” itself, but it can be noticed or even “created by the analyst” (Blimes 1998: 84). In Jaworski’s (2000: 113) terms it can be described as “an absence of something that we expect to hear on a given occasion, when we assume it is ‘there’ but remains unsaid.”

The phenomenon of “silencing” also needs to be included as an aspect of silence in communication. In interaction, one party may be silenced if another party does not allow space for talk. This is often found in institutional discourse where professionals or those with institutional authority may exercise control over the discourse (Eades, 2000, 2008; Fairclough, 1989; see also Chapter 20 in this volume by Diana Eades). As detailed below, silencing is often observed in intercultural communication where participants’ cultural backgrounds have different orientations to turn-taking (e.g. Eades 2008; Nakane 2005; Scollon 1985). Silencing may also take a form of suppression of information, for example through censorship, as discussed by Jaworski and Galasi![]() ski (2000) regarding an omission of information by the government of Poland through censorship.

ski (2000) regarding an omission of information by the government of Poland through censorship.

Silence is found extensively in communication. Some silences are noticeable, but others may not normally come to our attention. Awareness of the different forms of silence reveals a complex, ambiguous, yet finely tuned use of silence in communication.

Functions of Silence

Studies of silence have shown a wide range of functions, which can be grouped under the headings cognitive, discursive, social, affective, and semantic. These are described briefly in this section and will be referred to in the following sections in greater detail. First, silence phenomena such as pauses and hesitations have the function of earning cognitive processing time in communication. Chafe’s (1985) work on pauses in retelling a story showed that the lower the codability of items in the story, the longer the pauses. Sugit![]() (1991) reported that without pauses listeners had great difficulty in keeping up with ongoing talk and interpreting it correctly.

(1991) reported that without pauses listeners had great difficulty in keeping up with ongoing talk and interpreting it correctly.

Another function of silence is a discursive one, indicating junctures and meaning or grammatical units in speech. For example, units of speech defined by prosodic features such as intonation are often followed by pauses (Brown and Yule 1983). Jaworski (1993: 12) describes the discursive attribute of silence as “an important factor in defining the boundaries of utterance.”

There are also the social functions of silence. Jaworski (2000: 118) analyzes the use of silence and small talk in plays as literary sources, showing how social distance is created, maintained, and reduced by silence. He argues that with respect to the interpersonal metafunction “certain manifestations of silence and small talk may be treated as functional equivalents.”

Pause length and speech rate can also affect the formation of impressions in social encounters. From psychological perspectives, Crown and Feldstein (1985) suggest that length of pauses, as well as overall tempo of speech, can be associated with personal traits such as extroverted or introverted, and contributes to the listener’s impression of the speaker. In her study of courtroom discourse, Walker (1985) found that lawyers formed negative impressions of witnesses who had relatively frequent and long silent pauses although they had advised witnesses to use pauses to think carefully before they spoke. In intercultural communication, different pause length and speech rates are discussed in relation to culturally varied conversational styles, and may lead to problems and negative stereotyping, as will be discussed in detail below.

Silence can also be a means of social control. It can be used for punishment (Agyekum 2002; Nwoye 1985; Saville-Troike 1985), and it serves to reinforce and negotiate power relationships in various social encounters. Kurzon (1997) argues that while questioning in one-on-one situations gives power to the questioner, the respondent can reverse the situation by refusing to give a response. Gilmore (1985) discusses this negotiation of power – an attempt to overturn the power relationship by silence – in his study of students’ silent sulking in response to the teacher’s reprimand. A speaker may also lose status when addressees remain silent and do not take up his/her topic (Watts 1997). Thus, silences at different levels of discourse seem to be able to affect power relationships in communication.

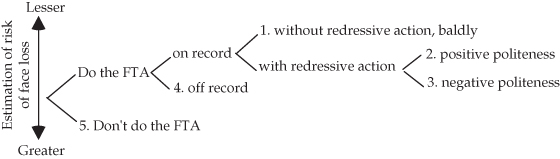

One important function of silence in social interaction is as a politeness strategy. Silence can be used to avoid unwanted imposition, confrontation, or embarrassment in social encounters which may have been unavoidable if verbal expressions had been used. In Brown and Levinson’s (1987) framework of politeness strategies (see Figure 9.1 below and also Chapter 11 by Janet Holmes in this volume) when the risk of threat to face is too great, one may decide not to perform that face-threatening act (FTA) at all (the “Don’t do the FTA” option). For instance, a student may say after class, without redressive action, to his/her classmate his/her answer to a math question is wrong (Do the FTA on record, without redressive action in Figure 9.1), as the risk of face loss in such context is relatively low. However, the same student may make an indirect suggestion that there may be a mistake (Do the FTA on record, with negative politeness), or may not say anything at all (Don’t do the FTA) when he/she thinks a professor has given incorrect information in his/her lecture. The assumption is that silence is the equivalent of the “Don’t do the FTA” strategy.

However, Sifianou (1997) argues that silence can be used as a positive politeness strategy when it functions as a sign of solidarity and good rapport, while it can also be a negative politeness strategy if it functions as a distancing tactic. It is also possible to use silence as an off-record strategy when it functions as the most indirect form of speech act. Talk and silence in relation to politeness strategies are also discussed by Scollon and Scollon (2001: 40–1), who list “Be voluble” as one of the positive (in their term, involvement) strategies and “Be taciturn” as one of the negative (independence) strategies. However, they do not identify solidarity-oriented silence as an involvement strategy. The various roles that silence plays in politeness show the importance of contextual factors, especially participants’ knowledge of and competence in using silence in interaction.

Silence also has an affective function. Saunders (1985) describes how serious emotional conflict can be avoided by use of silence in an Italian village. Avoidance of talk with a person who is extremely angry among the Western Apache (Basso 1972) is a way of managing intense emotional states. One can also use silence when no words can express an intense emotional state, and this can be exploited in the arts and literature for aesthetic effect (Davies and Ikeno 2002; Jaworski 1993). Kurzon (1997) refers to silence caused unintentionally by emotional states such as fear, embarrassment, and shame.

Finally, silence can be used to perform numerous speech acts with illocutionary and perlocutionary force to deliver propositional meanings in the most indirect way (Enninger 1987, 1991; Jaworski 1993; Saville-Troike 1985). As the example from Levinson (1983) above shows, a silent response to a first pair part of an adjacency pair such as a question or a request can often represent a dispreferred second (Blimes 1998; Levinson 1983). A silent response following an invitation is likely to imply it has been declined, and one following an offer is likely to imply rejection in English-speaking societies. A silent response following an information-seeking question can be regarded as a refusal to cooperate (Kurzon 1997).

As shown above, silence has almost as many functions as speech. Only those that are of high relevance for the subsequent discussion of silence in intercultural communication have been discussed. The multifaceted and ambiguous nature of silence described above suggests that its interpretation is highly context-dependent, and there are potential risks of miscommunication in intercultural encounters. This has a methodological implication in that research into the phenomenon of silence requires multiple perspectives and approaches to reach a reliable interpretation and understanding.

Silence and Cultures

Because silence is susceptible to various interpretations, using and interpreting silence are fine-tuned activities. This has brought attention to the potential risk of misunderstanding in intercultural communication (Enninger 1987, 1991; Jaworski 1993, 1997; Leech 1983; Saville-Troike 1985; Scollon 1985). Anthropologists were one of the earliest groups of researchers who turned their attention to culture-specific uses of silence. Their ethnographic approaches have revealed a wide range of situations and manners in which silence can be used in various communities. Some claim that children are socialized in their family environments to use these functions of silence, including community-specific uses, from an early age (e.g. Clancy 1986; Lehtonen and Sajavaara 1985; Philips 1972, 1983; Scollon and Scollon 1981). This may be why the use of silence may be more unconscious than speech and can cause problems in intercultural communication. Saville-Troike (1985: 12–13) explains:

Learning appropriate rules for silence is also part of the acculturation process for adults attempting to develop communicative competence in a second language and culture. Perhaps because it functions at a lower level of consciousness than speech, many (perhaps most) otherwise fluent bilinguals retain a foreign “accent” in their use of silence in the second language, retaining native silence patterns even as they use the new verbal structures.

One of the pioneering works on silence by an anthropologist is Basso’s (1972) study of a Western Apache Native American Indian community, which showed the important roles of silence in the social life of Apaches. Extensive observation, participation and interviewing in the community allowed Basso to provide detailed and in-depth accounts of how silence functions in a number of contexts in this particular community, and led to the conclusion that silence can be used in dealing with socially ambiguous situations. Similar ethnographic works that describe cross-cultural differences in uses of silence followed (e.g. Nwoye 1985; Scollon 1985; Philips 1983; Agyekum 2002). Some of this work has highlighted alternative views of silence, views that are not attached to negative values due to the “typical Western bias in treating speech as normal and silence as a deviant mode of behaviour” (Jaworski 1993: 46).

Silence in Intercultural Communication

Inter-Turn Pauses

Uses of silence can vary across cultures at both micro-and macro-levels of social organization. At a micro-level, length of pauses, especially cross-cultural differences in inter-turn pauses, has been one of the most extensively discussed issues in research into silence in communication. Sifianou’s (1997: 75) comment is representative: “the length of ‘gaps,’ types of fillers and amount of the overlapping talk are culture-specific. In some societies, gaps and silences are preferred to what is considered to be ‘idle chatter.’ In others, such idle chatter is positively termed as ‘phatic communion.’ ” In their discussion of the stereotypical image of “the silent Finn,” Lehtonen and Sajavaara (1985) suggest that Finns use long silent pauses in their talk compared to Southern Europeans or Anglo-Americans. Finnish speakers’ lengthy silences and lack of listener backchannels may thus suggest a lack of interest in and commitment to interaction with people from other cultural backgrounds. However, from the Finnish point of view, those features of silence are not intended to signify lack of interest or commitment (Carbaugh 2005). Carbaugh and Poutiainen (2000) report that Finnish speakers also allow longer silent pauses than American English speakers in self-introduction to show respect by taking time. They also suggest that American English speakers may be considered as talking too much in Finnish contexts as they try to cover the silence of their Finnish company. However, their claim is based on “comparison of the intuitive data” (Carbaugh and Poutiainen 2000: 194) and they reveal that the frequency of pauses and the rate of speech in the Finnish sample group do not show differences from those of other cultural groups.

One of the most prominent and earliest studies on silent pauses in intercultural communication is Scollon and Scollon’s (1981). They claim that Anglo-American English speakers often dominate conversations with Athabaskan Indian people because of the longer switching pauses of Athabaskan people. Thus, from Anglo-American perspectives, their communication with the Athabaskan people is perceived as a failure, as suggested by the title of Scollon’s (1985) paper, “The Machine Stops.” On the other hand, from the Athabaskan point of view, Anglo-Americans talk too much and are rude. Scollon and Scollon (1981: 25) note that Athabaskans’ tolerable length of silence is around 1.5 seconds, while Jefferson’s (1989) empirical study on the length of silent pauses in naturally occurring conversation found that native speakers of English seem to tolerate up to around 1.0 second of silent pause. Although his assumption is not based on a large set of data as in Jefferson (1989), Watts (1997: 93) claims that “at least within Western European and North American white culture” a silence of between 1.3 to 1.7 seconds and above will be significant and “open for interpretation” (94).

Enninger (1987, 1991) also reports long silent pauses in Amish interaction. Inter-turn silent pauses longer than 20 seconds are reported to have occurred at least 11 times in his 40-minute data of conversation among three Amish adults. He claims that among the Amish speakers “the putative universal of phatic communion appears to be replaced by an optional rule which produces a higher tolerance for between-turn silences” (Enninger 1991: 17). A possibility of “cross-cultural pragmatic failure” (Thomas 1983) is also suggested on the part of Amish speakers when interacting with mainstream American English speakers.

Tolerance of silence has also been attributed to Australian Aborigines (e.g. Eades 2000, 2008; Liberman 1985; Walsh 1997), in contrast with Anglo English speakers. Eades (2000; 2008; see also Chapter 20 in this volume) has demonstrated that Aboriginal witnesses are often prevented from giving their accounts by Anglo-Australian lawyers in Australian courtrooms due to their use of longer silences between turns, resulting in silencing of these witnesses. An empirical study on inter-turn pauses amongst Aborigines was recently reported by Mushin and Gardner (2009), who analyzed inter-turn pauses amongst Garrwa language speakers of remote Australian Aboriginal communities. They found that 1.5 seconds of gap, rather than Jefferson’s (1989) 1.0 second, appears to be “an indication of trouble” (Mushin and Gardner 2009: 2049) and silences longer than 1.0 second in talk occurred more frequently than in Anglo conversations. They argue that one of the reasons for the tolerance of silences is that the physical and social settings of the communities do not exert pressure for turn-taking. Mushin and Gardner (2009) also suggest that the intimacy among the participants allowed them to be less concerned about keeping the conversation going.

Longer silent pauses are also often attributed to the Japanese. Davies and Ikeno (2002: 51) claim that in a range of social interactions in Japan, “silence is much more common and is of longer duration than in Western countries.” Although their view is not based on an empirical study, Murata’s (1994) comparative study on interruptions, in which she analyzes recordings of conversations in Japanese–Japanese, English–English, and Japanese–English dyads, indicates Japanese participants’ stronger tendency towards avoidance of interruption. However, the Japanese participants interrupted more when speaking in English with English native speakers, suggesting accommodation in intercultural contexts. Nevertheless, observations similar to that of Davies and Ikeno (2002) above have been made in much literature, especially on Japanese students in ESL or study abroad contexts. Thorp (1991: 114), for example, comments on the adjustment she has made for Japanese students: “I did adapt to Japanese ideas concerning what was an acceptable pause length between speaker turns, and between question and answer. I soon realized that the Japanese have a far greater tolerance of silence than the British do, and I adapted to this.” Nakane (2007) gives examples of long pauses of up to 15 seconds in Japanese high-school classroom interaction, and demonstrates a possible transfer of the usage of long pauses by Japanese overseas students into Australian university classroom interaction. However, lack of familiarity with the “tutorial genre” in Australian classrooms on the part of the Japanese (Marriott 2000: 286) and disfluency in spoken English (Nakane 2007) may also be playing a role in silence of Japanese students overseas.

These varying orientations to inter-turn pause across cultures often lead to the domination of talk by one group over another, and consequently to negative stereotyping of each group. In most studies discussed above, the “dominant” group that is less tolerant of long silent pauses is Western Europeans or Anglo-Saxon speakers, and the medium of communication is often English. This means that members of the “dominated” group communicate in their second language, which may require a longer period of time for word-search and for processing what they have heard (Carbaugh 2005; Nakane 2007). Further research needs to be done examining English native speakers interacting in their second language, in order to investigate the impact of second-language proficiency more widely.

In terms of intra-group differences, Tannen (1984, 1985), through her analysis of interaction involving three New Yorkers, two Californians and one Briton, states that New Yorkers had a tendency to avoid silent pauses and prefer overlapping while the others found their communicative style domineering and rude. This suggests that even within American culture, there may be different orientations to tolerable length of inter-turn pauses. Tannen (1984) also found the British participant the most silent, pointing out a British–American contrast in tolerance for silence. Sifianou (1997: 78) compares Greek and British orientations to silence and observes a similar contrast, where Greeks prefer “cooperative overlap” while “overlapping talk is not easily tolerated” among the British. These studies indicate that any “Western” versus “non-Western” dichotomy needs careful consideration.

It should also be noted that pauses of the same length can be interpreted differently as contextual factors affect their significance and meaning to a great extent (cf. Mushin and Gardner 2009; Nakane 2007; Watts 1997), and thus careful analysis of pause length and contextual factors is also required.

Communicative Silence Carrying Propositional Meaning

Silence that realizes illocutionary force and carries propositional meaning seems to exist almost universally. However, such use of silence may be culturally specific, and therefore could lead to misinterpretation of “user” intention or meaning in intercultural contexts. A rather extreme example given by Saville-Troike (1985: 9), based on Williams (1979) and Nwoye (1978), is that silence of a woman to a marriage proposal by a man is interpreted as an acceptance in Japanese whereas it is a rejection in Igbo. Although the Japanese example is likely to have become less typical in recent years, it serves to illustrate the possibility of cultural differences in the interpretation of silences occurring in similar situations. The non-verbal expressions accompanying silence may also have an important role in the interpretation process, and these expressions can be culturally fine-tuned features of communication as well.

There are some types of silent speech acts performed by Japanese that have drawn special attention in existing research. Disagreement and rejection are commonly mentioned speech acts that tend to be performed through silence in Japanese (cf. Nakane 1970; Clancy 1986; Enninger 1987; Maynard 1997; Ueda 1974). Chie Nakane’s (1970: 35) comment illustrates this: “One would prefer to be silent than utter words such as ‘no’ or ‘I disagree.’ The avoidance of such open and bald negative expressions is rooted in the fear that it might disrupt the harmony and order of the group.” Enninger (1987) notes that the Japanese discourse system does not follow Levinson’s (1983) statement that dispreferred seconds are more morphologically marked than preferred seconds, and are often preceded by a delay (i.e. gap), as dispreferred seconds “do not always take an elaborate formal exponent” in Japanese (Enninger 1987: 294). This use of silence to indicate disagreement also serves to avoid loss of face, which will be discussed below.

However, long silent pauses in the position of second pair parts are likely to be interpreted as prefaces to dispreferred seconds or even as the dispreferred seconds themselves (see the earlier example from Levinson 1983). Thus, silence in place of disagreement or rejection may not be a communicative behavior particularly unique to Japanese people. It could be what happens after the silence itself that causes puzzlement to non-Japanese. McCreary’s (1986) example of silence as a dispreferred second in Japanese–American business negotiation is followed by another adjacency pair in which the Japanese negotiator responds with the preferred “yes” without really meaning to agree but only indicating that he is attending to his American negotiator’s suggestion. Thus, it is important to analyze what silences are “doing” in relation to the contexts and sequences in which they occur. It should also be mentioned that confrontation and argument do take place in Japan, but in private rather than public (Miller 1994), for example, at home with family members (Ueda 1974).

Silence and Politeness

A commonly expressed view in literature on silence is that cultures with negative politeness orientation tend to use silence more extensively than cultures with positive politeness orientation. This is consistent with the association made by Brown and Levinson (1987) and Scollon and Scollon (1995, 2001) of volubility with positive politeness and taciturnity with negative politeness, although the latter uses the terms “involvement” and “independence.” Tannen (1984: 30) describes enthusiasm and volubility on the part of the Greeks, in contrast with the Americans, a “high-involvement conversational style” (see also Chapter 8 in this volume), which resonates with Scollon and Scollon’s (1995) involvement politeness orientation. Tannen (1984: 28) demonstrates how misunderstanding may occur when interactants bring different orientations to talk and silence by giving an example of a Greek-background woman (with a high-involvement style) misinterpreting the intention of a one-word response, “Okay,” as a sign of unwillingness when her American husband was simply expressing his willingness casually. Similarly, Sifianou (1997: 75) argues that the English, with negative politeness orientation, are “relatively more silent” than the Greeks who have positive politeness orientation and thus prefer a “high-involvement style” of interaction (78).

It is often argued that East Asian societies such as China, Japan, and Korea are on the “negative” end of the politeness continuum and have stronger preference for silence. Bailey (2000) discusses a conflict between Korean migrant retailers and African-American customers in Los Angeles, where the latter find the former lacking in respect as they do not reciprocate small talk. This illustrates a clash between positive politeness orientation (of African-American customers) and negative politeness orientation (of Korean migrants) represented in divergent orientations to talk and silence. Ellwood (2004, 2009) examines Japanese students’ silence as a face-saving strategy in contrast with their voluble European student classmates who, in the words of a Japanese student, “do not hesitate to answer even if the answer is incorrect” (Ellwood 2004: 141) in Australian-language classrooms. Nakane (2006), through her analysis of Japanese students in Australian university seminars, suggests that the Japanese seem to overestimate face-threat in Australian classroom interaction, resulting in being perceived as silent, withdrawn, and formal. In her study, Japanese students also used silence more extensively as various politeness strategies, including an off-record strategy to communicate that they did not know the answer, while Australian students tended to verbalize such a message. Liu (2002) also attributes silence of Chinese students in the US partly to their deference towards the teacher who would not be challenged in their own culture. Silence used to attend to the negative face of the teacher is a marked silence in the US tertiary classroom context where the estimation of threat to the teacher’s face caused by questions or critical comments is lower than in China. Tatar (2005) also reports silence as a face-saving strategy used by Turkish graduate students in US classrooms. Nevertheless, the extent to which cultural orientation to politeness plays a role in the use of silence needs further exploration. It is possible that classroom silence as a face-saving strategy may be more strongly associated with lack of confidence in language proficiency in non-native speakers than with cultural identity. Ellwood (2004), for example, reports that at least one French student in her study did not speak in class due to her lack of confidence in English.

Silence and Negotiation of Power

Silence may be used in negotiating institutionally or socially defined roles and associated power relationships. In the Akan community, the king uses silence to mark his “power, authority, rank, and status” (Agyekum 2002: 42). However, the use of silence can also mark subordination. Lebra’s (1987: 351) explanation on social hierarchy and silence in Japanese communication illustrates this point: “silence is an inferior’s obligation in one context and a superior’s privilege in another, symbolic of a superior’s dignity in one instance and of an inferior’s humility in another.” An instance of this contradiction can be seen in a British study by Roberts and Sarangi (2005) that discusses a Somalian woman who does not offer information because of her expectation that the doctor will know it.

Distribution of talk and silence among speakers may also be associated with power. In a comparative study that analyzed American and Japanese group discussions, Watanabe (1993) found that the Japanese group selected a leader, the oldest male participant, who led the discussion, while in the American group, each individual contributed in a free-for-all participation mode without a hierarchical orientation to the discussion.

The cultural divergence in terms of association between silence and power can also be found in the contrast between Athabaskan Indian and Anglo-American cultures. Scollon and Scollon (1981) argued that subordinate people are not supposed to display their abilities verbally in front of their superiors in Athabaskan communities whereas it is almost the opposite in Anglo-American culture. In a similar vein, Philips (1972) explains the silence of children by comparing learning processes in the Warm Springs Indian community, which values learning through observation and mimicking of adults, and the mainstream American communities, where verbalizing in front of others and questioning mentors is valued.

Silence has also been identified as a strategy for resisting power. Gilmore (1985: 155), for example, claims that black students in a school in the US used stylized silent sulking to show defiance against teachers and to “turn the loss of face back to the teacher” when confronted. Additionally, cross-cultural observation is made in this study, where black teachers do not tolerate this silence while white teachers are more tolerant, finding the sulking intimidating, but yet trying to understand it as “cultural variation in communication” (1985: 157). Gilmore (1985) argues that such acceptance will rather marginalize the youths from the broader society.

Situation-Specific Silences

Communities often have rules in which certain member(s) do not speak or are not to be spoken to in some specific situations. Enninger (1987: 272) distinguishes between this type of situation-specific silence and culture-specific silence, but specific situations in which silence is assumed or practiced can also vary across cultures (Jaworski 1993). In some communities, religious ceremonies and rituals may be delivered in silence, partly accompanied by non-verbal expressions or gestures (e.g. Agyekum 2002; Basso 1972; Nwoye 1985). Silence can also be observed in certain situations among the Apache such as where silence towards a family with a recent loss is a sign of “intense grief” (Basso 1972: 78). Moreover, in this situation, silence is believed necessary because the family is regarded as going through a personality transformation due to their loss. Clair (1998) reports female relatives in mourning remaining silent in contact with others for two years in the Warramunga indigenous Australian community. Similarly, in the Akan community in Ghana (Agyekum 2002) and the Igbo community in Nigeria (Nwoye 1985), a long period of silence takes place when contact between bereaved family members occurs. In the Akan community, silence is also used as a form of social control as community members refuse to talk to “people who violate socio-cultural norms” to deter “future violators” (Agyekum 2002: 39). The Igbo is reported to have the same use of silence (Nwoye 1985). These uses of silence appear to be often related to management of intense emotion and extreme events in life.

While the above examples entail total lack of speech in specific situations, intercultural gaps in amount of talk and silence in specific communicative events may lead to communicative problems and negative cultural stereotyping. In first encounters among strangers in Athabaskan Indian culture (Scollon and Scollon 1981), observation and silence are the norm, while small talk is the way to establish a relationship among Anglo-Americans. Similarly, Carbaugh (2005) demonstrates that, in first encounters, Finnish speakers’ use of silence is much longer and more frequent than Americans, which often leads to a negative perception of Americans as superficial by the Finns and of Finns as shy and silent by Americans. The conflict, mentioned above, between Korean migrants and African-American customers in Los Angeles (Bailey 2000) is also another example of how different orientations to small talk result in misunderstanding. A similar gap has been observed by Walsh (1997) in a remote Australian indigenous community where extensive silence was observed in his first encounters with local Aboriginal people. The tight-knit community structure that allows people to be connected closely and share assumptions may be associated with the lack of need for “small talk.” A non-dyadic and continuous interactional style in Australian Aboriginal communities (Walsh 1994) may explain tolerance and normative uses of extensive silence that would be a marked phenomenon in mainstream Anglo-Australian society.

Being Silent About Specific Topics

Another aspect of silence which may have impact on intercultural communication is what not to talk about. In other words, topics that are avoided may vary across cultures. For instance, future plans and talking about hope are avoided by Athabaskans but are generally welcomed by Anglo-Americans (Scollon and Scollon 1981). In Aboriginal communities in Australia, there are topics which can only be mentioned by women or men. These topics have been called “secret women’s business” and “secret men’s business” (Moore 2000: 138). In Australian Aboriginal communication there are numerous other strict restrictions on what certain members of a community can talk about, and topics which are allowed for speaking are distributed according to traditional rules in each community, which Walsh (1994: 225) calls “knowledge economy.”

The distribution of talk and silence in relation to topics can also reinforce the power relationship involving certain cultural groups, as shown by Berman’s (1998) study on Javanese women’s silence regarding their unsatisfactory work conditions. This silence was a form of censorship, where the social expectation of these women’s silence prevented them from speaking out about their oppressed status. Similarly, Sheriff (2000: 114) describes “cultural censorship” of the topic of racism among poor Brazilians of African descent in Brazil. It is apparent that this type of silence is related to the oppression of marginalized and powerless groups in society, and as Berman (1998) demonstrates, the oppressed group is empowered when such silence is broken.

Attitudes to Silence

Attitudes to silence are another area that has attracted substantial attention in intercultural communication research. For instance, Carbaugh (2005), Lehtonen and Sajavaara (1985), and Sajavaara and Lehtonen (1997) report that the Finns often attach a positive value to silence on social occasions. Eades (2000) and Walsh (1997) describe how Aboriginal people in Wadeye in Australia can sit together without uttering a word for a long period of time, a situation which would make Anglo-Australians uncomfortable. Similarly, communities such as the Western Apache (Basso 1972), the Athabaskan (Scollon 1985; Scollon and Scollon 1981), the Igbo (Nwoye 1985) and the Amish (Enninger 1987, 1991) are found to be more tolerant of silence and attach a more positive value to silence than do “Western” communities.

The Japanese are one group who are often described as attaching strong values to silence, and as making abundant use of silence (Doi 1974; Clancy 1986; Davies and Ikeno 2002; Lebra 1987). Such claims, however, have generally not been based on empirical findings. Thus, there have been remarks that this stereotype is inaccurate. For example, Anderson (1992: 102) states: “Japanese do talk, and at times they talk a lot. But the contexts in which talk is culturally sanctioned, and the types of talk that occur in these settings, do not correspond to those of the West.” The opposite perspective has also been challenged. The “typical Western bias” (Jaworski 1993: 46) expressed by Argyle (1972: 107–8) for example, that “[in] Western cultures, social interaction should be filled with speech, not silence,” has been empirically tested by Giles et al. (1991). In their study, university students of Anglo-American, Chinese-American, and Chinese (non-American) background completed questionnaires on their beliefs about talk and silence. The results confirmed the “Western bias,” with the Anglo-Americans viewing talk more positively than the other two groups, while the non-American Chinese group saw silence more positively. The Chinese-American group came in the middle in their valuation of silence and talk. However, within the “Western” group, different levels of valuation of silence and talk can be found (e.g. Sifianou 1997; Tannen 1984, 1985; see also Chapter 8 in this volume). Giles et al. (1991) in a different study also found that Hong Kong students viewed small talk more positively than students in Beijing, and there is also a generational gap in beliefs about talk and silence. It is worth noting that the common view of Asian students being unwilling to participate has been criticized in a number of studies that reported Asian students’ desire to be articulate in class (e.g. Ellwood 2004; Ellwood and Nakane 2009; Littlewood 2000). In the literature on silence, the comparison between “Western” and “non-Western” cultures is prevalent, but who is included under the term “Western culture” is ambiguous, and the use of the general label “Western” may contribute to and reinforce the stereotyping of voluble or silent racial groups.

It is also important to note that people from communities that are associated with positive attitudes to silence do not necessarily wish to or indeed stay silent when they participate in intercultural communication. This can be explained partly by the theory of linguistic accommodation (Giles et al. 1973, 1991), although it is not always possible to accommodate linguistic practices if one lacks ability to do so (Bourhis et al. 1975). One such ability is the language proficiency of second-language speakers. In addition, interactional practices into which they have been socialized may not easily allow second-language speakers to accommodate to the interactional norm of talk and silence in the L2 environment and when interacting with L1 speakers who are already versed in the interactional norms of the host community. Furthermore, the majority of existing studies discuss silence in monolingual situations or in English-medium interaction where it is non-native speakers of English who are often found to be the silent group. There is a dearth of research on silence in lingua franca situations or in communication where the medium of language is not English.

Silence and Second-Language Speakers

In considering silence in intercultural communication it is often necessary to address issues in relation to the use of second language by one or more of the participants. Naturally, language proficiency affects participation in interaction, but second-language anxiety has been claimed to be one of the major factors associated with silence, in both language classrooms and mainstream program classrooms (e.g. Lehtonen et al. 1985; Volet and Ang 1998; Young 1990). The issue of proficiency and perceptions of it can be complex in that spoken language proficiency may not always reflect lexico-grammatical or written language proficiency, and contextual factors such as topic and participants may also affect one’s proficiency as well as confidence in second-language production in intercultural communication (cf. Nakane 2007). In his discussion of Chinese students’ silence at a US university, Liu (2000) suggests that personality and gender are related to participation modes in that introverted students and female students show a stronger tendency to remain silent in class, while linguistic factors on their own did not predict level of participation. Second-language learners may also have unrealistic expectations and evaluations of themselves and peers which may contribute to their silence (Ellwood 2004; Lehtonen et al. 1985).

Second-language speakers may have difficulty in adopting or accommodating to interactional norms of their interactants or of their host community, or vice versa, which may result in marked silence in intercultural communication. One such type of difficulty is related to participation norms. Marriott (2000: 286) reports that Japanese postgraduate students at a university in Australia have difficulties in participating in tutorials because the “Japanese students had not experienced any tutorial genre in Japan” and “important sociolinguistic norms concern not only complex turn-taking rules but also the content of such talk.” Similarly, Liu (2000) described the Chinese students he observed as “overwhelmed by native English speakers in class” (165) who showed an “active participation mode” (183).

Another aspect of interactional norms that may affect silence is level of elaboration in speech production. Young and Halleck (1998) report Japanese students’ under-elaboration in oral proficiency interviews in English, in comparison with the discourse of Mexican students. Ross (1998: 339) also discusses Japanese interviewees’ silence as a marked behavior which is negatively evaluated by the assessor and explains it as an approach “in which they transfer the pragmatics of interview interaction from their own culture.” Marriott (1984) also discusses under-elaboration by Japanese in social contexts in Australia which is perceived negatively by Australians. However, Ross (1998) does not identify the number of participants, and Young and Halleck (1998) examine only six students with different proficiency levels, which leaves questions about the validity of their claims.

Returning to second-language anxiety, as Lehtonen et al. (1985) suggest, in encounters between non-native and native speakers it is possible that non-native speakers opt for silence if they anticipate negative outcomes from speaking. In this sense, the silence of the non-native speaker can be a face-saving strategy. However, at the same time, having to accommodate to non-native speakers and make special efforts to communicate can be face-threatening for native speakers. Gass and Varonis (1991: 124) show an example of how this may be avoided by native speakers:

An American university student once told us that if she were walking down the street and saw her NNS conversation partner [an international student paired up with her for mutual language practice] when she was particularly tired, she would turn around and walk the other ways [sic] so as not to engage in what would undoubtedly be a difficult and stressful conversation.

On the other hand, non-native speakers may, like hearing-impaired people (Jaworski and Stephens 1998), prevent loss of face by avoiding asking native speakers to repeat.

Research into classroom silences of students from minority communities who speak the language of the classroom as their second language often discusses the relationship between the silence and the marginalization of such minority groups. Jaworski and Sachdev (1998: 276) have suggested that the multiethnic and multilinguistic educational environment is strongly associated with a “culture of silence.” Ortiz (1988) found that Mexican American students are called on 21% less frequently than their Anglo-American peers in American mainstream classrooms. The teachers explained that they preferred to avoid embarrassing students for their poor English or feeling embarrassed themselves if any miscommunication was to occur. In her study of an English composition classroom at a college, Losey (1997) found that Mexican Americans initiated talk far less frequently than their Anglo-American classmates. Moreover, Mexican American female students who made up 47% of the class made only 12.5% of initiations and 8% of responses. As major factors creating and reinforcing Mexican American women’s silence in the classroom, Losey (1997) lists negative self-perception as a powerless and silenced minority compounded with language differences, cultural differences and teachers’ perceptions, along with approaches to these differences. Even when Mexican students manage to respond or initiate, interruption by the teacher or peers frequently occurs, silencing them. The teacher in Losey’s (1997) study was committed to her students, but the silence of the Mexican American women caused her to form a negative perception of them, and consequently this was reflected in her communication with them in the classroom.

It should be noted here that in all these classroom studies, the majority group seems to be made up of English-speaking Anglo-Saxons. Little is known about whether Anglo-Saxon English speaking students as a minority group would be more silent if in a majority group of non-Anglo peers. One study that examined such a situation is that of Harumi (1999), who compared the use of silence by Japanese learners of English and British learners of Japanese. Her study showed that British learners used silence in their communication in Japanese, although their silence was often accompanied by explicit non-verbal expressions such as eye-gaze, posture, or head movements, showing willingness to participate (1999: 183). As for the Japanese learners of English, drawing on interpretations elicited from both Japanese native speakers and English native speakers, she claimed that their non-verbal expressions accompanying silence were not “clear enough” to communicate their intention and were, thus, “problematic” (1999: 182). However, the sample groups were very small, and studies such as Harumi’s (1999) need to be carried out on a larger scale.

There is also an important area of research that addresses “the silent period” in second-language learning. Although it is beyond the scope of this chapter, there are a number of views on what is meant by the silent period, what acquisition process takes place during such period, and what approaches should be taken pedagogically in relation to it (see for example Hakuta 1976; Gibbons 1985; Granger 2004; Krashen 1985; Saville-Troike 1988).

Concluding Remarks

As the above overview of research on silence in intercultural communication shows, silence can emerge or be noticed when comparisons between the communicative styles of distinct communities are made. Communication may be avoided due to anticipation of negative consequences of intercultural communication when different orientations to talk and silence are perceived, further reinforcing the silence of one group and the dominance of the other. At the same time, cultural stereotypes are also reinforced, which widens the gaps between cultures. Hence, perceptions of marked silences or unexpected volubility can entail further silence or dominance of one group. This type of amplification of problems in intercultural communication is known as “complementary schismogenesis” (Bateson 1972). Thus, it is important to recognize the role of stereotypes in the interpretation of silence.

Furthermore, the prevalent dichotomy which aligns talk–silence with “West–East” is under question, as findings of studies that demonstrate variation within “West” and “East” suggest. Within communities that may be regarded as having a strong tendency towards and preference for talk, there are those who suffer from the pressure to be articulate in every aspect of social life. Lehtonen et al. (1985: 56) say that one in five Americans feels apprehensive about communication because of a pressure in their culture where articulate verbal performance “is considered to be one of the most important measures for success and positive image.” While silence is often associated with problems in intercultural communication research, critical views on the positive valuation of the ability to be articulate in the “West” are beginning to emerge in communication research (e.g. Cameron 2000), and alternative approaches to research in talk and silence in intercultural communication could make valuable contributions.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Agyekum, K. 2002. The communicative role of silence in Akan. Pragmatics 12(1), 31–52.

Anderson, F. E. 1992. The enigma of the college classroom: Nails that don’t stick up. In P. Wadden (ed.). A Handbook for Teaching English at Japanese Colleges and Universities. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 101–10.

Argyle, M. 1972. The Psychology of Interpersonal Behaviour. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Bailey, B. 2000. Communicative behaviour and conflict between African-American customers and Korean immigrant retailers in Los Angeles. Discourse and Society 11(1), 86–108.

Basso, K. H. 1972. “To give up on words”: Silence in Western Apache culture. In P. Paolo Giglioli (ed.). Language and Social Context. Harmondsworth: Penguin. 67–86.

Bateson, G. 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. New York: Ballantine.

Berman, L. 1998. Speaking through the Silence: Narratives, Social Conventions, and Power in Java. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Blimes, J. 1998. Being interrupted. Language in Society 26(4), 507–31.

Bourhis, R. Y., H. Giles, and W. E. Lambert. 1975. Social consequences of accommodating one’s style of speech: A cross-national investigation. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 6, 55–72.

Brown, G. and G. Yule. 1983. Discourse Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, P. and S. C. Levinson. 1987. Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge: 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press.

Cameron, D. 2000. Good to Talk? Living and Working in a Communication Culture. London: Sage Publications.

Carbaugh, D. A. 2005. Cultures in Conversation. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Carbaugh, D. A. and S. Poutiainen. 2000. By way of introduction: An American and Finnish dialogue. In M. W. Lustig and J. Koester (eds.). Among US: Essays on Identity, Belonging, and Intercultural Competence. New York: Addison and Wesley Longman. 203–12.

Chafe, W. L. 1985. Some reasons for hesitating. In D. Tannen and M. Saville-Troike (eds.). Perspectives on Silence. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. 77–89.

Clair, R. P. 1998. Organizing Silence: A World of Possibilities. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Clancy, P. 1986. The acquisition of communicative style in Japanese. In B. B. Schieffelin and E. Ochs (eds.). Language Socialisation across Cultures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 213–50.

Crown, C. L. and S. Feldstein. 1985. Psychological correlates of silence and sound in conversational interaction. In D. Tannen and M. Saville-Troike (eds.). Perspectives on Silence. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. 31–54.

Davies, R. J. and O. Ikeno. 2002. The Japanese Mind. Boston, MA: Turtle Publishing.

Doi, T. 1974. Some psychological themes in Japanese human relationships. In J. C. Condon and M. Saito (eds.). Intercultural Encounters with Japan: Communication – Contact and Conflict. Tokyo: Simul Press. 17–26.

Eades, D. 2000. I don’t think it’s an answer to the question: Silencing Aboriginal witnesses in court. Language in Society 29(2), 161–95.

Eades, D. 2008. Courtroom Talk and Neo-Colonial Control. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Ellwood, C. 2004. Discourse and desire in a second language classroom. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Technology Sydney, Australia.

Ellwood, C. 2009. Uninhabitable identifications: Unpacking the production of racial difference in a TESOL classroom. In R. Kubota and A. M. Y. Lin (eds.). Race, Culture, and Identities in Second-Language Education. London and New York: Routledge. 101–17.

Ellwood, C. and I. Nakane. 2009. Privileging of speech in EAP and mainstream university classrooms: A critical evaluation of participation. TESOL Quarterly 43(2), 203–30.

Enninger, W. 1987. What interactants do with non-talk across cultures. In K. W. Knapp, W. Enninger, and A. Knapp-Potthoff (eds.). Analyzing Intercultural Communication. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 269–302.

Enninger, W. 1991. Focus on silence across cultures. Intercultural Communication Studies 1, 1–37.

Fairclough, N. 1989. Language and Power. London: Longman.

Gass, S. M. and E. M. Varonis. 1991. Miscommunication in nonnative speaker discourse. In N. Coupland, H. Giles, and J. M. Wiemann (eds.). “Miscommunication” and Problematic Talk. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. 121–45.

Gibbons, J. P. 1985. The silent period: An examination. Language Learning 35(2), 255–67.

Giles, H., N. Coupland, and J. Coupland. 1991. Accommodation theory: Communication, context and consequence. In H. Giles, J. Coupland, and N. Coupland (eds.). Contexts of Accommodation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1–68.

Giles, H., D. M. Taylor, and R. Y. Bourhis. 1973. Towards a theory of interpersonal accommodation through language: Some Canadian data. Language in Society 2, 177–92.

Gilmore, P. 1985. Silence and sulking: Emotional displays in the classroom. In D. Tannen and M. Saville-Troike (eds.). Perspectives on Silence. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. 139–62.

Goffman, E. 1967. Interaction Ritual. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Granger, C. A. 2004. Silence in Second Language Learning: A Psychoanalytic Reading. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Hakuta, K. 1976. A case study of a Japanese child learning English as a second language. Language Learning 26(2), 321–51.

Harumi, S. 1999. The use of silence by Japanese learners of English in cross-cultural communication and its pedagogical implications. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Institute of Education, University of London.

Hymes, D. 1972. On communicative competence. In J. B. Pride and J. Holmes (eds.). Sociolinguistics: Selected Readings. Harmondsworth: Penguin. 269–93.

Jaworski, A. 1993. The Power of Silence: Social and Pragmatic Perspectives. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Jaworski, A. 1997. Introduction: An overview. In A. Jaworski (ed.). Silence: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 3–14.

Jaworski, A. 2000. Silence and small talk. In J. Coupland (ed.). Small Talk. London: Longman. 110–32.

Jaworski, A. and D. Galasi![]() ski. 2000. Strategies of silence: Omission and ambiguity in the Black Book of Polish censorship. Semiotica 131(1/2), 185–200.

ski. 2000. Strategies of silence: Omission and ambiguity in the Black Book of Polish censorship. Semiotica 131(1/2), 185–200.

Jaworski, A. and I. Sachdev. 1998. Beliefs about silence in the classroom. Language and Education 12(4), 273–92.

Jaworski, A. and D. Stephens. 1998. Self-reports on silence as a face-saving strategy by people with hearing impairment. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 8(1), 61–80.

Jefferson, G. 1989. Preliminary notes on a possible metric which provides for a “standard maximum” silence of approximately one second in conversation. In D. Roger and P. Bull (eds.). Conversation: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. 166–96.

Krashen, S. D. 1985. The Input Hypothesis: Issues and Implications. London: Longman.

Kurzon, D. 1997. Discourse of Silence. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Lebra, T. S. 1987. The cultural significance of silence in Japanese communication. Multilingua 6(4), 343–57.

Leech, G. N. 1983. Principles of Pragmatics. London: Longman.

Lehtonen, J. and K. Sajavaara. 1985. The silent Finn. In D. Tannen and M. Saville-Troike (eds.). Perspectives on Silence. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. 193–201.

Lehtonen, J., K. Sajavaara, and S. Manninen. 1985. Communication apprehension and attitudes towards a foreign language. Scandinavian Working Papers on Bilingualism 5, 53–62.

Levinson, S. C. 1983. Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Liberman, K. 1985. Understanding Interaction in Central Australia: An Ethnomethodological Study of Australian Aboriginal People. Boston, MA: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Littlewood, W. 2000. Do Asian students really want to listen and obey? ELT Journal 54(1), 31–5.

Liu, J. 2000. Understanding Asian students’ oral participation modes in American classrooms. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication 10(1), 155–89.

Liu, J. 2002. Negotiating silence in American classrooms: Three Chinese cases. Language and Intercultural Communication 2(1), 37–54.

Losey, K. M. 1997. Listen to the Silences: Mexican American Interaction in the Composition Classroom and the Community. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Maltz, D. N. 1985. Joyful noise and reverent silence: The significance of noise in Pentecostal worship. In D. Tannen and M. Saville-Troike (eds.). Perspectives on Silence. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. 113–37.

Marriott, H. 1984. English discourse of Japanese women in Melbourne. Papers of the Japanese Studies Centre 12, 38–46.

Marriott, H. 2000. Japanese students’ management processes and their acquisition of English academic competence during study abroad. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication 10(2), 279–96.

Maynard, S. K. 1997. Japanese Communication: Language and Thought in Context. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

McCreary, D. R. 1986. Japanese–U.S. Business Negotiations: A Cross-Cultural Study. New York: Praeger.

Miller, L. 1994. Japanese and American meetings and what goes on before them: A case study of co-worker misunderstanding. Pragmatics 4(2), 221–38.

Moore, B. 2000. Australian English and indigenous voices. In D. Blair and P. Collins (eds.). English in Australia. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 133–49.

Murata, K. 1994. Intrusive or cooperative?: A cross-cultural study of interruption. Journal of Pragmatics 21(4), 385–400.

Mushin, I. and R. Gardner. 2009. Silence is talk: Conversational silence in Australian Aboriginal talk-in-interaction. Journal of Pragmatics 41(10), 2033–52.

Nakane, C. 1970. Japanese Society. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Nakane, I. 2005. Negotiating silence and speech in the classroom. Multilingua 24(1–2), 75–100.

Nakane, I. 2006. Silence and politeness in intercultural communication in university seminars. Journal of Pragmatics 38(11), 1811–35.

Nakane, I. 2007. Silence in Intercultural Communication: Perceptions and Performance in the Classroom. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Nwoye, G. O. 1978. Unpublished manuscript. Georgetown University. Ref. in M. Saville-Troike (1984). The Ethnography of Communication: An Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.

Nwoye, G. O. 1985. Eloquent silence among the Igbo of Nigeria. In D. Tannen and M. Saville-Troike (eds.). Perspectives on Silence. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. 185–91.

Ortiz, F. I. 1988. Hispanic-American children’s experiences in classrooms: A comparison between Hispanic and non-Hispanic children. In L. Weis (ed.). Class, Race, and Gender in American Education. New York: State University of New York Press. 63–86.

Philips, S. U. 1972. Participant structures and communicative competence: Warm Springs children in community and classroom. In C. B. Cazden, V. P. John, and D. Hymes (eds.). Functions of Language in the Classroom. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press. 370–94.

Philips, S. U. 1983. The Invisible Culture. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

Roberts, C. and S. Sarangi. 2005. Theme-oriented discourse analysis of medical encounters. Medical Education 39, 632–40.

Ross, S. 1998. Divergent frame interpretations in language proficiency interview interaction. In R. Young and A. Weiyun He (eds.). Talking and Testing: Discourse Approaches to the Assessment of Oral Proficiency. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 333–53.

Sacks, H., E. Schegloff, and G. Jefferson. 1974. A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language 50(4), 696–735.

Sajavaara, K. and J. Lehtonen. 1997. The silent Finn revisited. In A. Jaworski (ed.). Silence: Interdisciplinary Perspective. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 263–83.

Saunders, G. R. 1985. Silence and noise as emotion management styles: An Italian case. In D. Tannen and M. Saville-Troike (eds.). Perspectives on Silence. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. 165–83.

Saville-Troike, M. 1985. The place of silence in an integrated theory of communication. In D. Tannen and M. Saville-Troike (eds.). Perspectives on Silence. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. 3–18.

Saville-Troike, M. 1988. Private speech: Evidence for second language learning strategies during the “silent period.” Journal of Child Language 15, 567–90.

Scollon, R. 1985. The machine stops. In D. Tannen and M. Saville-Troike (eds.). Perspectives on Silence. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. 21–30.

Scollon, R. and S. B. K. Scollon. 1981. Narrative, Literacy, and Face in Interethnic Communication. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Scollon, R. and S. Wong Scollon. 1995. Intercultural Communication: A Discourse Approach. Oxford: Blackwell.

Scollon, R. and S. Wong Scollon. 2001. Intercultural Communication: A Discourse Approach. 2nd edn. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Sheriff, R. E. 2000. Exposing silence as cultural censorship: A Brazilian case. American Anthropologist 102(1), 114–32.

Sifianou, M. 1997. Silence and politeness. In A. Jaworski (ed.). Silence: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 63–84.

Sugit![]() , M. 1991. Danwa bunseki: Hatsuwa to p

, M. 1991. Danwa bunseki: Hatsuwa to p![]() zu [Discourse analysis: speech and pause]. Nihongogaku [Japanese Linguistics] 10, 19–30.

zu [Discourse analysis: speech and pause]. Nihongogaku [Japanese Linguistics] 10, 19–30.

Tannen, D. 1984. Conversational Style: Analysing Talk among Friends. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Tannen, D. 1985. Silence: Anything but. In D. Tannen and M. Saville-Troike (eds.). Perspectives on Silence. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. 93–111.

Tannen, D. and M. Saville-Troike. 1985. Perspectives on Silence. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Tatar, S. 2005. Why keep silent? The classroom participation experiences of non-native-English-speaking students. Language and Intercultural Communication 5(3–4), 284–93.

Thomas, J. 1983. Cross-cultural pragmatic failure. Applied Linguistics 4(2), 91–112.

Thorp, D. 1991. Confused encounters: Differing expectations in the EAP classroom. ELT Journal 45(2), 108–18.

Ueda, K. 1974. Sixteen ways to avoid saying “no” in Japan. In J. C. Condon and M. Saito (eds.). Intercultural Encounters with Japan: Communication – Contact and Conflict. Tokyo: Simul Press. 185–92.

Volet, S. and G. Ang. 1998. Culturally mixed groups on international campuses: An opportunity for inter-cultural learning. Higher Education Research and Development 17(1), 5–23.

Walker, A. G. 1985. The two faces of silence: The effect of witness hesitancy on lawyers’ impressions. In D. Tannen and M. Saville-Troike (eds.). Perspectives on Silence. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. 55–75.

Walsh, M. 1994. Interactional styles in the courtroom: An example from northern Australia. In J. Gibbons (ed.). Language and the Law. London: Longman. 217–33.

Walsh, M. 1997. Cross-cultural Communication Problems in Aboriginal Australia. Canberra: North Australia Research Unit, Australian National University.

Watanabe, S. 1993. Cultural differences in framing: American and Japanese group discussions. In D. Tannen (ed.). Framing in Discourse. New York: Oxford University Press. 176–209.

Watts, R. 1991. Power in Family Discourse. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Watts, R. 1997. Silence and the acquisition of status in verbal interaction. In A. Jaworski (ed.). Silence: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. 87–115.

Williams, H. 1979. Unpublished manuscript. Georgetown University. Ref. in M. Saville-Troike (1984). The Ethnography of Communication: An Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.

Young, D. J. 1990. An investigation of students’ perspectives on anxiety and speaking. Foreign Language Annals 23(6), 539–53.

Young, R. and G. B. Halleck. 1998. “Let them eat cake!” or how to avoid losing your head in cross-cultural conversations. In R. Young and A. Weiyun He (eds.). Talking and Testing: Discourse Approaches to the Assessment of Oral Proficiency. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. 355–82.