8

Turn-Taking and Intercultural Discourse and Communication

When people engage in conversation, they take turns speaking. This seems at first a self-evidently simple matter: one talks, then another talks, then another. But how do speakers know when their turn at talk has come? How do they accomplish the exchange of turns? For what reasons and in what ways do speakers take turns that others believe they are not entitled to? Moreover, what are the consequences when participants in a conversation have different assumptions about how to answer these questions? It is obvious to everyone that being raised in different cultures and speaking different languages entails learning different grammars and lexicons. It is somewhat less obvious that languages and cultures may also come with different practices and ideologies about exchanging turns. Because turn-taking habits operate automatically, they tend to be invisible, so when they differ, people are likely to interpret the consequences as resulting from interlocutors’ intentions (e.g. You only want to hear yourself talk) and abilities (e.g. You have nothing to contribute to this conversation).

Perceived violations of turn-taking are typically labeled interruption. This designation attributes the disruption in turn exchange to one party’s behavior and intentions. But perception and intention are not always the same. Just because one person feels interrupted does not mean that the other intended to interrupt. Moreover, anything that occurs in conversation is rarely the doing of one speaker. It almost always results from the interaction of participants’ behavior: each utterance is not only the cause of another’s response but is itself a response to another’s prior utterance. Thus understanding turn-taking and its relation to cultural patterning provides a window on the workings of conversational interaction as well as on intercultural communication.

Overview

To demonstrate how turn-taking habits affect intercultural interaction, I begin by describing a study I conducted of a dinner table conversation among American friends. Because the speakers had grown up in different parts of the United States, their conversation showed the effects of subcultural differences in turn-taking practices. I then discuss the place of turn-taking studies in discourse analysis, focusing on studies of overlap and interruption in a range of cultural contexts. Some of the studies discussed examined turn-taking in a single culture; some juxtaposed and compared intracultural interaction in two or more cultures; and some looked at intercultural interactions. Most of these studies examined what was identified as interruptions, often tracing this result to differences in pacing, pausing, and attitudes toward silence in interaction. Some, however, also uncovered other factors, including: frequency and type of back-channel verbalization; paralinguistic and prosodic features such as pitch, amplitude and intonation; nonverbal features including gaze, smiling, and head nods; and assumptions about the rights and responsibilities that accrue to relative social rank. I then consider studies conducted in the field of language and gender, because many of them have sought to assess patterns of interruption. These studies are significant not only for their findings but also because evaluating their findings problematizes the complexity of turn-taking in particular and of research methodology in general. In sum, research that explores the effects of turn-taking practices and ideologies on intercultural interaction also sheds light on the process of turn-taking in intracultural discourse.

Turn-Taking in Intercultural Perspective

Turn-taking habits played a major role in accounting for the consequences of subcultural differences in a dinner table conversation among American friends that I examined in an early study (Tannen [1984] 2005). Three of the conversational participants (of whom I was one) had grown up in New York City; two had been raised in Southern California; and one had been raised in London.1 Close analysis of a transcript of the conversation and the timing of pauses revealed that the three New Yorkers expected shorter pauses between turns than did the others – or no perceptible pause at all. It happened frequently that while the Californians and the British speaker were waiting for a pause that would signal an open floor, a New Yorker, perceiving that the turn-exchange length of pause had come and gone, began speaking. As a result, it was difficult for the non-New Yorkers to negotiate turns at talk. This did not mean that they could not participate at all. During playback (a step in discourse analysis by which participants are played excerpts of a conversation and asked to comment), a Californian remarked that he felt he hadn’t been able to “fit in.” I pointed out that he had frequently been the center of attention. He responded that, yes, he could be the center of attention or he could be an observer, but he could not just be “part of the flow” – that is, participate in the give-and-take of smooth turn exchange (Tannen [1984] 2005: 62).

In addition to expecting differing length of pauses between turns, the New Yorkers and non-New Yorkers had different assumptions and habits with regard to simultaneous speech, or overlap. The New York-bred speakers frequently talked along when another was speaking as a show of enthusiastic listenership. Because the non-New Yorkers did not use overlap in this way, they frequently mistook these “cooperative overlaps” as attempts to take a turn, that is, to interrupt. Acting on this interpretation, they usually stopped speaking, so the cooperative overlap did turn into an interruption – a result that each regarded as the other’s doing.

The pattern observed in this conversation, by which New Yorkers were more voluble, was not a function of participants’ specific turn-taking habits – that is, one group expecting long pauses and the other expecting short ones. It was, rather, a function of the interaction of contrasting styles. A person who is voluble when talking to someone who expects longer inter-turn pauses will be taciturn in conversation with someone who expects shorter ones. To illustrate this process, I will describe a series of interactions involving myself, a native of Brooklyn, New York, and my colleague Ron Scollon, who grew up in the midwestern city of Detroit. I learned over time that in conversation with Ron, I had to count to seven after I got the impression that he had nothing to say, in order to give him time to perceive that I was done and he could begin. But when Ron talked to his wife Suzie Scollon, he found himself in the role of inadvertent interrupter. Suzie, who was raised in Hawaii, often complained to her husband, “You ask me a question, but before I can answer you ask another.” Her sense of a normal inter-turn pause was longer than his. Ron and Suzie Scollon did field work in an Athabaskan village in northern Canada. They and other researchers have documented that Athabaskan conversational conventions typically entail relatively long inter-turn pauses and periods of silence. When Suzie spoke to native Athabaskans, she was often the one who ended up interrupting.

This story doesn’t end there. One year Ron Scollon invited me to take part in a meeting that he organized at the University of Fairbanks in Alaska, where he was on the faculty. After the meeting ended, I visited an Athabaskan village, Fort Yukon, located just inside the Arctic Circle. Later that term, Ron gave his students a mid-term exam in which he included the question: “Deborah Tannen recently visited Fort Yukon. What do you think was her experience there?” Since the students had read my analysis of the dinner table conversation, they were familiar with the way I had characterized my own conversational style. Most of them answered correctly that because I get to know people by talking to them, while Athabaskans tend to prefer silence until they feel they know each other, conversation with village natives had been impossible. (In the end I had resorted to contacting the local missionary, whom I’d met at the meeting.) But a student who had been raised in a village much farther north in the Arctic Circle wrote, “People in Fort Yukon talk so fast, she probably fit right in.”

Evidence for Intercultural Turn-Taking Patterns

Because conversation is an oral/aural phenomenon that takes place in real time, the discourse analysis of conversation makes use of transcripts that represent speech in written form, fixed in time. Transcripts make it possible to examine conversational discourse closely. In order to illustrate how transcripts can provide concrete evidence for the consequences of differing turn-taking habits, I will present three examples from my study of dinner table conversation. The first example is taken from an exchange between speakers whose styles differ. The second and third present excerpts from talk among speakers whose style is shared.

Example 1: The Disruptive Effect of Intercultural Differences

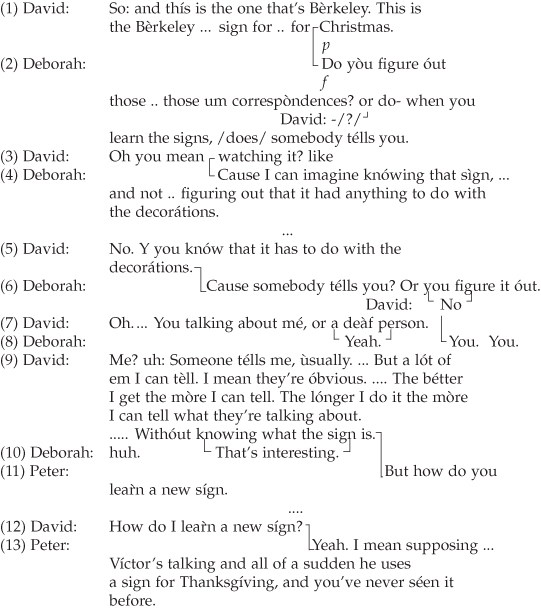

Example 1 illustrates the disruption in the rhythmic flow of conversation that can occur when speakers have different turn-taking habits. David, a professional sign language interpreter, has just told the group that he knows three different signs for the word “Christmas.” The sign he is demonstrating here, he has just explained, represents Christmas decorations.2

As shown by the brackets, my questions in turns (2), (4), and (6) and Peter’s in turns (11) and (13) either overlap or latch onto David’s comments. (Latching refers to beginning a turn so soon after a previous turn that no pause is perceptible.) Peter and I share what I call a “high-involvement style” (whereby speakers show good will by emphasizing their connection to others) while David’s style is what I call “high-considerateness” (whereby speakers show good will by emphasizing their efforts to not impose on others). The rapidity of Peter’s and my questions are intended to encourage David in his discourse by showing interest, but they have the opposite effect, disrupting David’s fluency, because they come as overlaps or latches. One might expect a smooth exchange of turns to follow the pattern “question–answer–pause,” but Example 1 exhibits an odd rhythm that can be characterized as “answer–question–pause.” That is, questions come rapidly after answers, while answers are preceded by pauses. This can be seen in the pauses indicated by spaced dots before David’s replies in turns (5) and (12).

Further evidence of David’s discomfort with the pace of Peter’s and my questions is the disfluency and hesitance evident in his responses. As soon as David demonstrates the sign for Christmas that refers to Christmas lights in turn (1), I ask him, in turn (2), how he knows the iconic referents of signs. Rather than answering my question, David asks for clarification in (3) “Oh you mean watching it?” David told me during playback that abrupt questions catch him off guard, and he had experienced my question as abrupt because, among other things, it came as an overlap. Unaware of this at the time, I do not slow down and give David more time to reply; instead, I expand on my question in an effort to make it easier for him to answer: (4) “Cause I can imagine knówing that sìgn, … and not .. figuring out that it had anything to with the decorátions.” David’s reply in (5) “ No. Y you knów that it has to do with the decorátions” does not answer my question; he tells me that he knows, whereas I had asked how he knows. I therefore follow up by giving him what amounts to a multiple choice question in (6) “Cause somebody télls you? Or you figure it óut.” Yet even this form of the question does not elicit an answer. Instead David asks for clarification in (7) “Oh. …You talking about mé, or a deàf person.” Only after I respond with a clipped (8) “You. You. ”does David finally answer, but his reply includes evidence of his continuing, indeed increasing, discomfort:

Me? uh: Someone télls me, ùsually… But a lót of em I can tèll. I mean they’re óbvious… The bétter I get the mòre I can tell. The lónger I do it the mòre I can tell what they’re talking about… Withóut knowing what the sign is.

In this turn, David finally answers my question (“they’re obvious”), but his reply is characterized by hesitation, pauses, repetition, and a kind of rambling, all of which indicate his discomfort.

I did not suspect at the time that David’s disfluency was a response to the form of my questions: they were too quick, too clipped, and too loud, and also abruptly switched focus from sign language in general to his personal experience as a signer – all elements of high-involvement style meant to show enthusiastic interest in him and his discourse. Then, to make matters worse, when I finally give up, Peter takes over, asking in (11) “But how did you lea![]() n a new sígn.” David responds the same way to Peter’s question as he did to mine: (11) is followed by a relatively lengthy pause, after which David simply repeats the question: (12) “How did I lea

n a new sígn.” David responds the same way to Peter’s question as he did to mine: (11) is followed by a relatively lengthy pause, after which David simply repeats the question: (12) “How did I lea![]() n a new sígn?” Again, I know now, because David explained it to me later, that this repetition, like the others that came before, were his instinctive attempt to slow down the pace of the conversation.

n a new sígn?” Again, I know now, because David explained it to me later, that this repetition, like the others that came before, were his instinctive attempt to slow down the pace of the conversation.

Some readers might find it self-evident that Peter’s and my overlaps and latches were interruptive. Wouldn’t anyone react as David did? The next two examples, taken from same-style exchanges, provide evidence that overlaps were not taken as interruptions but rather encouraged the flow of talk when used in conversation with fellow high-involvement-style speakers.

Example 2: The Flow of Talk When Turn-Taking Habits Are Shared

Immediately prior to the interchange that appears as Example 2, the topic was the impact of television on children. After Steve expressed his opinion, I asked a series of fast-paced questions relating to Steve’s childhood, which also apply to Peter, who is his brother. Despite the overlaps and latches, there was no disfluency. When a question of mine overlapped his talk, Steve simply completed what he was saying and went on to answer my question with no hitch in fluency or timing. (Quonset huts were temporary housing that was built for veterans returning to the United States after having served abroad in World War II.)

In this interchange, the fast pace of my questions is matched by the pace of Peter’s and Steve’s replies. In addition, I abruptly switch focus from general to personal, just as I did in Example 1, but with very different results. In turn (1), Steve expresses his belief that television has done children more harm than good. I respond to this general comment with a question that switches the focus to him personally: (2) “Did yóu two grow up with télevision?” While Peter is replying: (3) “Véry little. We hád a TV in the Quonset” I overlap to ask another question: (4) “Hów old were you when your parents got it?” Steve’s next turn constitutes evidence that the overlap did not throw him. The first part of this turn answers my first question, about whether he and Peter grew up with television: (5) “We hád a T![]() but we didn’t wátch it all the tíme.” Then he goes on to answer my second question about how old he was: “We were véry young. I was foúr when my parents got a TV.” Peter’s use of “we” in “We hád a TV” orients to my having addressed my question to “you two” in “Did you two grow up with television?” However, his use of “I” in “I was four…” is oriented to the potential singular referent in my question “Hów old were you…?” The fluency with which Peter and Steve answer my overlapping and latching questions gives an idea of how the same style of questions that had a negative effect with David had a positive effect with fellow high-involvement style speakers: greasing rather than gumming up the conversational wheels.

but we didn’t wátch it all the tíme.” Then he goes on to answer my second question about how old he was: “We were véry young. I was foúr when my parents got a TV.” Peter’s use of “we” in “We hád a TV” orients to my having addressed my question to “you two” in “Did you two grow up with television?” However, his use of “I” in “I was four…” is oriented to the potential singular referent in my question “Hów old were you…?” The fluency with which Peter and Steve answer my overlapping and latching questions gives an idea of how the same style of questions that had a negative effect with David had a positive effect with fellow high-involvement style speakers: greasing rather than gumming up the conversational wheels.

Example 2 also includes another, very different type of illustration of high-involvement style in action. Whereas the lines just discussed show that fast-paced, overlapping questions can be answered without disfluency, turns (10) and (11) show that such questions need not be answered at all. In (10) I ask how old Steve and Peter were when they lived in Quonset huts. This question is followed by a pause, after which Steve offers a comment that is only tangentially related to my question: (11) “Y’know my fàther’s dentist said to him whát’s a Quónset hut. … And he said Gód, yóu must be younger than my children. … He wás. … Yoùnger than bóth of us. ” Just as Steve had no trouble replying to questions that overlapped or latched his turns, he also felt free to ignore a question when he had something else he wanted to say. The fact that rapid-fire questions could be ignored without provoking any sign of discomfort or even notice in anyone, helps explain why they would not be experienced as intrusive. Indeed, the very aspects of these questions that make them intrusive to David – fast pace, high pitch, and overlapping or latching timing – are precisely the aspects that have the opposite effect with Steve and Peter, for whom they signal casualness, as if to imply, “Answer if you feel like it, but if you don’t feel like answering, then don’t bother. My only purpose here is to encourage you to keep talking.”

Example 3: Putting Shared Style to Use

Here is one last example of how transcripts afford concrete evidence of turn-taking at work in conversation. Example 3 shows that shared style facilitates participation, whereas familiarity with a topic does not. In the following brief excerpt, Steve is describing a location in New York City. I overlap to suggest a landmark that I think identifies the location he has in mind, and Peter overlaps both of us to echo my suggestion.

Steve then goes on to clarify the spot he is referring to.

Had Peter and I both been right in identifying the geographic location Steve is describing, this interchange would not have attracted my notice. But how could he and I have made the same mistake? I asked Peter about this during playback, and he explained that he didn’t really know that section of New York City very well. He assumed that I did, so he piggy-backed on my utterance, and offered the same suggestion. From the point of view of content, this misfired, since I was wrong and therefore he was wrong, too. But from the point of view of participating in the conversation, Peter’s gambit worked perfectly. It allowed him to participate in the interchange and to demonstrate his attentive listening. Ironically, the British participant in the conversation, Sally, told me during playback that she did know the spot Steve was referring to, but she couldn’t say so because the pace of the conversation made it impossible for her take a turn. In other words, Peter’s familiarity and facility with the use of cooperative overlap were sufficient for him to take part in the conversation, whereas Sally’s knowledge of the subject under discussion was not. Anyone who has experienced intercultural conversation will recognize the frustration from both points of view: on one hand, having something to say but being unable to find a way to say it, and, on the other, the surprise of learning that someone else present had known something relevant but did not say it.

The Place of Turn-Taking Studies in Discourse Analysis

Analysis of turn-taking has been foundational to the academic study of conversational interaction from its inception. The article that introduced and established the subfield known as Conversation Analysis, or CA, which was published in Language, the flagship journal of the Linguistic Society of America, was entitled “A Simplest Systematics for the Organization of Turn-Taking for Conversation” (Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson 1974). Setting the stage for innumerable studies that have followed, this article established the exchange of turns as a starting point for the analysis of conversational discourse. It also established the premises that conversation follows an unstated rule that one speaker talks at a time, and that turn exchange is expected to take place at “transition-relevance places,” that is, points at which a speaker could be perceived as having completed a turn. When more than one speaker talks at a time, it is either a mistake or a violation of these rules. If simultaneous speech occurs at transition-relevance places, it is judged to be a mistake. If an interactant begins speaking at a point that is not a transition-relevance place, the resultant simultaneous speech is judged to be an interruption.

The work of Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson was based on American conversation. Subsequent studies questioned the universality of the one-speaker-at-a-time premise by examining turn-taking in other cultures. Reisman (1974) coined the term “contrapuntal conversations” to suggest that talk in Antigua, West Indies did not reflect the assumption that only one voice should be heard at a time. Quite the opposite, Reisman found, in many Antiguan contexts overlapping voices were expected and valued. Many subsequent studies have documented similarly frequent and positively viewed uses of overlap in a range of cultures. Moerman (1987) did so for Thai conversation, as did Hayashi (1988) for Japanese and Sidnell (2001) for Guyanese. Duranti (1997) suggested the term “polyphonic discourse” to describe Samoan ceremonial greetings in which speakers routinely overlap one another. These overlaps often are not at transition-relevance places, yet they are regarded not as interruptions but rather as a “joining-in” to welcome a newcomer.

In these and other similar studies, analysts demonstrate that cooperative overlapping is every bit as systematic as the one-speaker-at-a-time turn-taking organization. Though the overlapping voices may seem chaotic to outsiders, community members do not begin speaking without regard to others’ speech; they automatically gauge when and in what way it is acceptable to overlap. Duranti, for example, shows that incoming speakers are attuned to those they overlap, because they often repeat or paraphrase prior speakers’ utterances. He finds evidence that overlaps are not perceived as interruptions in that first speakers do not stop and second speakers do not recycle their turns (Duranti 1997: 359).

Speicher (1996) draws similar conclusions about what she calls “parallel talk” among Filipino-American college students at an affinity group meeting. She describes the exuberant simultaneous talk as “multiple voices vying for the floor, joking, cajoling, asserting, conversing, and suggesting,” all at once (Speicher 1996: 419). Students who were not participating in one interchange began another concurrent one. In subsequent interviews, participants identified this type of simultaneous talk as typical of Filipino gatherings, and evinced almost uniformly positive evaluations of it. Speicher provides evidence for the specifically Filipino character of this type of conversation in the way that participants switched to non-overlapping styles in the presence of non-Filipinos.

These studies support the observation that specific ways of speaking cannot be assigned a single meaning. Like all conversational strategies, overlapping talk is ambiguous: it can be experienced as a negative move, an interruption, or a positive one, a “joining-in.” It is also polysemous; that is, it can mean both. Speicher, for example, notes that while the parallel talk she observed among Filipino-American college students had “a competitive edge,” yet students who engaged in this type of talk valued it and explained that they talked that way because they felt “close” (1996: 420). Thus, there are contexts in which overlaps are perceived as interruptions yet are still cooperative in nature. If both or all participants agree that interruption is acceptable or even desirable, and they interrupt one another in equal measure, then their overlaps are simultaneously both interruptive and cooperative.

Intracultural Variation in the Use of Overlap in Turn Exchange

Whereas these and other studies have demonstrated that there are cultures in which overlap is sought rather than avoided and valued positively rather than negatively, many also have shown that uses of overlap vary by context within a given community. For example, Besnier (2009: 101), describing the cultural significance of gossip on Nukulaelae Atoll in the Central Pacific, notes that speaking-along contributes to “warmth and interpersonal harmony,” “conviviality and sociability,” and the sense of connection that is reflected and established by the sharing of a stance toward others’ behavior that is gossip. Importantly, however, he observed overlapping speech in some gossip exchanges but not others. Convivial overlap characterized gossip in which speakers discussed common-knowledge information, but not when a speaker informed another of previously unknown information. Thus, use of overlapping speech is not only culturally relative but also situation-specific within a cultural community.

Similarly, a study by Liao (2009) introduces a note of caution against assuming that patterns of overlap or interruption observed in a single context necessarily define a culture’s practices; instead, they may reflect constraints specific to that context. In a study of interruption patterns in Chinese criminal courtroom discourse, Liao found that Chinese criminal trials are characterized by more interruptions than American trials, yet this pattern is not indicative of generalizable cultural differences with regard to interruption. It results from the constraints of the countries’ respective legal systems. Chinese lawyers interrupt defendants far more often than their American counterparts because they are not permitted to ask leading questions (those requiring a yes/no answer); they must ask “wh-” questions, which tend to be broader. As a result, defendants’ replies frequently fail to address the points that the lawyer hopes to elicit. The lawyers’ interruptions are attempts to redirect the testimony. Because American lawyers are able to control defendants’ testimony by asking leading questions during cross-examination, they have less need to interrupt.

Attitudes toward Silence and their Relation to Turn-Taking

Much of the work on turn exchange takes for granted two assumptions: first, that speakers agree that conversational space should be filled with talk, and second, that speakers seek the floor. Thus the floor is seen as a prize to be won, and conversation is conceptualized as a competition for that prize, the speaker who gains the floor having won the competition. This assumption underlies the frequent characterization of interruptive overlaps as “competitive.” Both these assumptions have been questioned. Scollon (1985), for example, used an intercultural perspective to question the universality of what he characterized metaphorically as the sense that silence in conversation constitutes a malfunction of machinery that should be chugging along. He shows that Athabaskan speakers value silence in conversation, and in many contexts they prefer not to have the floor. This is a stance that shy people in any culture might recognize and share.

In a similar spirit, Watanabe (1993), comparing small group discussions among Japanese and American college students respectively, observed that whereas American students valued and sought the right to speak, Japanese students saw holding the floor as a liability they preferred to avoid. As a result of these differing attitudes, the highest-ranking American participant gained the privilege of speaking first, whereas among the Japanese students, the lowest-ranking participant ended up with that disfavored responsibility. These findings are consonant with Yamada’s (1997) observation that Japanese tend to value silence while Americans tend to value speech. The evidence Yamada cites includes such contrasting proverbs as Americans’ “The squeaky wheel gets the grease” and the Japanese “Tori mo nakaneba utaremaji,” “If the bird had not sung it would not have been shot” (1997: 17).

Numerous studies have observed a relationship among attitudes toward silence, rate of speech, and patterns of listener verbalization. For example, Stubbe (1998) compared the use of listener overlap by native Maoris and by Pakehas (New Zealanders of European descent). She found that Pakehas exhibited and expected more listener feedback, and they expected it to come more quickly, whereas Maoris exhibited and expected less, especially less verbal feedback, and it may be delayed. With these different baselines, the same amount of feedback will be considered excessive by Maoris and deficient by Pakehas, eliciting attendant negative interpretations. She further noted that Pakehas’ greater expectation of explicit verbal feedback is associated with a tendency to avoid silence, whereas Maoris were more comfortable with silence and with indirect or deferred feedback. Yet she also noted that there are contexts in which Pakehas expect silence and Maoris tend to verbalize. For example, in formal public contexts, Maoris often express their approval of a speaker’s remarks by interjecting “ae” or “kia ora” whereas Pakehas listen in silence, perhaps expressing approval with non-verbal signals such as nodding or, at most, laughter (Stubbe 1998: 263).

Gardner and Mushin (2007) analyzed a conversation between two indigenous Australian women speaking in a mixture of Aboriginal English and two indigenous languages, Garrwa and Kriol. Citing their own findings as well as those of other Australianists, they note two seemingly paradoxical patterns: on one hand, speakers of native Australian languages show a greater tolerance for long periods of silence and longer inter-turn pauses. At the same time, though, there were contexts in which the authors observed more overlapping talk among native Australians. They also identified a type of overlap that they felt was not described by Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson, which they dubbed “post-start-up overlap.” So far from occurring at transition-relevance places, these overlaps begin shortly after another has begun speaking.

Gardner and Mushin’s observations are an important reminder of the complexity of turn-taking patterns. It might initially seem surprising, even inherently contradictory, to find a higher tolerance for long pauses or silence co-existing with greater use of simultaneous speech. But the same has also been described for Japanese conversation. Yamada (1997) documents far more silence and far longer pauses in Japanese business conversations than in Americans’. She reports that American audiences become visibly uncomfortable when she reads aloud an excerpt of an interchange that took place at a Japanese meeting and uses a stopwatch to accurately represent an eight-second pause between turns. Yet Hayashi (1988: 280) documents “the extraordinary frequency of simultaneous talk” in Japanese conversation, ranging from “one word or phrase to more than two sentences,” and sometimes involving three or four people. She notes, “A long simultaneous talk of back channel lasting for 3–4 sec [sic] of the speaker’s utterance is not rare in Japanese interaction.” Key here is the term “back channel,” which refers to verbalization that shows listenership but does not claim the floor.

Two important factors are at work here. One is the distinction between types of overlap, based on whether the intent is intrusive or cooperative. In both the Australian and the Japanese cases, the overlap described is supportive in nature. The other factor is the distinction between two types of pauses, which Scollon (1985) identifies as switching pauses and in-turn pauses. The long pauses (which go along with a high tolerance for silence) in Australian and Japanese discourse are switching pauses, which occur between turns. They can thus be interpreted as high-considerateness, leaving plenty of space to make sure a speaker is ready to yield the floor. The overlapping described in these cultural styles is primarily a within-turn phenomenon. That is, listeners talk along without claiming a turn. Interestingly, I observed the reverse pattern among high-involvement-style speakers: though they often used brief or no switching pauses, as demonstrated above, they also used relatively long in-turn pauses for dramatic effect. An example of this is Steve’s turn (1) in Example 2:

As shown by the spaced dots, and as can be heard in the audio clip, Steve speaks slowly, leaving perceptible pauses at four separate locations in his utterance. Together with low pitch and volume, the pauses lend an air of weightiness to his statement about the effect of television viewing on children.

Researchers examining turn-taking patterns in a range of cultures, then, have questioned the universality of the one-speaker-at-a-time premise of turn exchange. Yet a study by Stivers et al. (2009) has confirmed that claim. The authors examined the exchange of turns in videotaped conversations in ten languages. Focusing on question/answer sequences in which questions called for yes/no answers, they concluded that conversations in all ten languages evinced “a general avoidance of overlapping talk and a minimization of silence between conversational turns.” They did, however, “find differences across the languages in the average gap between turns” (p. 10,587). They attribute the perception that some languages favor overlap or silence to a subjective impression resulting from “a natural sensitivity” to these very small differences in tempo. This insight explains why the one-speaker-at-a-time and the culturally relative turn-taking perspectives can both be right: The differences may be very small, but even very small differences can have large effects in intercultural communication.

The dinner conversation among Californians, New Yorkers, and a British speaker that I described above is one of many studies that have identified major effects of small cultural differences in turn-taking practices. Another such study in the American context is Shultz, Florio, and Erickson’s (1982) ethnographic observation of two Italian-American children in a suburb of Boston. Their teacher had complained that many students in her class “interrupted” frequently. The authors, after observing and videotaping the children in their homes and at school, identified differences in turn-taking conventions in these two contexts. In family conversations overlapping speech frequently occurred without anyone reacting as if it were inappropriate. At school, however, when the teacher was enforcing a “one speaker at a time” rule, she heard children’s overlapping speech as “interrupting.”

Many researchers have found English speakers more often interrupting speakers of other languages than the other way around, especially when they converse with speakers from cultures that value silence or favor longer pauses. In keeping with Scollon’s previously cited finding that Athabaskans favor silence and are comfortable with longer pauses, Scollon and Scollon (1981) found that in intercultural interactions, English speakers interrupted Athabaskans more than they were interrupted by them. Similarly, building on an early study by Lehtonen and Sajavaara (1985) that found Finns to favor silence and longer inter-turn pauses, Halmari (1993) examined twelve business telephone conversations, six between Finns and six between a Finn and an American. She found that speakers of American English initiated overlapping speech more than three times as often as did speakers of Finnish. She also found differences in where the overlaps occurred. Finns tended to initiate overlaps during the last phoneme or last word of another’s utterance, while Americans tended to begin speaking in the middle of another’s utterance or turn.

Non-Verbal and Paralinguistic Signaling in Turn Exchange

Studies of intercultural interaction often bring into focus phenomena that go unnoticed when style is shared. Thus analyses of intercultural interaction have provided insight into many aspects of turn-taking. Yamada (1997) demonstrates that Japanese expectations of longer periods of silence and longer inter-turn pauses are only one factor among many that can cause problems in business conversations between Japanese and American speakers. She notes numerous other factors as well. For example, Japanese speakers modify their verbal behavior according to the respective ranks of the speakers. In a corporate banking meeting attended by two Americans and two Japanese, an American office manager, Claire, is apparently “bullied” by a Japanese vice president, Tanaka, who derails her presentation and “robs her of her right to talk on her own topic.” Claire attributes this uncomfortable outcome to male chauvinism on the part of Japanese men, but Yamada believes it resulted from Tanaka’s assumption that his higher rank obligated him to carry the burden of talk.3 She contrasts this with other meetings at which the Japanese participants exert efforts to even out the amount of talk, because they regard their American interlocutors – male or female – as equal in rank (Yamada 1997: 102–3).

Yamada describes another source of intercultural misunderstanding: the Japanese tendency to provide more frequent listener feedback, both verbal (such as Hayashi [1988] also documented) and non-verbal (in the form of smiling and head-bobbing). These differences disrupted turn exchange for both American and Japanese speakers, but for different reasons. Japanese speakers often stopped mid-turn, awaiting the expected feedback, while Americans stopped mid-turn because they interpreted the Japanese listener behavior as attempts to take the floor. Causing further problems, Americans often interpreted Japanese head-bobbing and verbal feedback to indicate agreement, when it was intended only to show listenership. From the Americans’ point of view, their Japanese colleagues were not trustworthy, because they indicated agreement when they didn’t really agree. (Interestingly, this parallels exactly a gendered pattern described by Maltz and Borker [1982]; they noted that women tend to provide and expect more listener feedback such as “yeah,” “mhm,” and “uhuh,” so they often get the mistaken impression that men are not listening when they are, while men often mistake women’s signs of listenership for signs of agreement, and feel misled when they later learn that the women did not agree.)

Some turn-taking studies have focused on the role played by paralinguistic features such as pitch, amplitude, rhythm, and intonation. For example, in order to determine whether instances in which an interactant begins to speak while another is already speaking is interruptive (in their terms, “turn-competitive”) or simply “overlapping,” Wells and MacFarlane (1998) examined ten minutes of an hour-long naturally occurring conversation among a British family, with most of the talk taking place between a mother and daughter. The researchers concluded that interruptive incomings were characterized by high pitch and loud volume. A similar pattern has been documented for discourse in a different context and language. Examining seven hours of Malay audio broadcast interviews, Zuraidah and Knowles (2006) also conclude that prosodic features characterize overlaps as competitive or non-competitive. The ceding of a turn is signaled by decreased pitch and loudness, while the competitive taking of a turn is characterized by increased pitch and loudness, and sometimes also by increased speed.

Another non-verbal signal of turn exchange is gaze. Stivers et al. (2009) found that speakers who fix their gaze on listeners elicit faster responses. They further note that a non-verbal cue such as a head nod or even an eyebrow flash could constitute a turn. Erickson (1986) also documents the importance of gaze patterns while speaking and listening. An example comes from a series of uncomfortable moments that occurred in a job interview. The interviewer had grown up in a rural small town in Indiana, in a family tracing its roots back at least five generations to forebears from Germany. The young man he was interviewing had grown up in an Italian neighborhood in Chicago, to parents born in Italy. The interviewee seemed inarticulate and nervous, his speech characterized by hesitation, pausing, and repetition, along with physical movements such as squirming slightly in his seat. On close inspection, Erickson observed that the young man’s hesitation and discomfort occurred when the interviewer broke gaze and looked at his coffee cup. This pattern was repeated three more times: the young man began speaking when the interviewer was looking at him, became disfluent when the interviewer looked away, then became fluent again when the interviewer resumed direct eye contact. During a playback interview, the young man identified the interviewer’s gaze pattern as evidence that he was not interested in what the applicant was saying: “He was staring at his coffee cup and this signified to me that he doesn’t care…” (Erickson 1986: 304). For his part, the interviewer explained during a playback interview that he noticed the young man was uncomfortable, so he decided to give him more space, just let him talk, to help him relax. Ironically, the very gaze pattern that he used while trying to help the interviewee relax was causing discomfort.

Acknowledging the importance of non-verbal feedback introduces a cautionary note with regard to studies based only on audio recordings. Stubbe (1998), for example, based her analysis of Maori and Pakeha supportive overlap on the Wellington Corpus of Spoken New Zealand English. After noting that she found far more cooperative overlapping by Pakehas, she cautions that Maoris tend in general to use more non-verbal signals in their interaction than Pakehas.

Turn-Taking and Gender

If analysis of turn-taking has been foundational in the field of CA, a particular type of turn-taking violation – interruption – has been foundational in the field of gender and language. The primary goal of most of this research has been to use analysis of turn-taking to understand gender relations. But research in this domain has also provided insight into the nature of conversational floors and the process of turn exchange. For example, in what quickly became a classic study, Edelsky (1981) set out to determine how much women and men talked, respectively, at a faculty meeting. She concluded that in order to address this question, she had to distinguish between two types of floor: one in which a single speaker talks while others listen or respond, and another, which she calls “collaborative,” characterized by what can come across as a “free-for-all.” Whereas men talked more in the former floor, women and men talked equally in the latter. (She noted that women didn’t talk more in collaborative floors; men talked less.) In other words, in the process of studying language and gender, Edelsky made a contribution to our understanding of conversational floors.

In an early and influential study written in the CA tradition, West (1979) analyzed cross-gender conversation and concluded that men interrupted women more often than the reverse. This study (also reported in West and Zimmerman 1983) occasioned innumerable subsequent studies that examined gender differences in patterns of interruption, some supporting and some questioning West’s observations. In almost immediate response, Bennett (1981) pointed out that whereas overlap is a descriptive category, a matter of observing that two voices are heard at the same time, interruption is an interpretive category that reflects observers’ judgments of speakers’ intentions and rights to the floor. Bennett’s comment constitutes a reminder that distinguishing between overlap and interruption presents a methodological challenge facing all analysts of turn exchange in conversation.

Anderson and Leaper (1998), surveying forty-three previously published studies, concluded that findings with regard to gendered patterns of interruption depend on whether the overlap is intrusive or collaborative, as well as the situation. They report that studies focusing specifically on intrusive interruptions confirmed West’s finding that men interrupted more than women. Furthermore, findings of this pattern were “more likely and larger in magnitude” when the data were gathered in natural settings rather than laboratory experiments and when speakers were observed in groups rather than dyads. Perhaps most intriguing among the results of their survey was the observation that it is not only the sex of the speakers that influences research findings. The sex of the researcher plays a role as well. Intrusive interruptions were more likely to be found, and the observed differences were likely to be greater, when the first author was a woman.

Many of the studies inspired by West found women overlapping more than men in same-sex conversation. For example, Coates and Sutton-Spence (2001) compared the signed conversation of two groups of Deaf friends, one all-men and the other all-women. They concluded that the “one-at-a-time model” accurately described the men’s conversation but not the women’s, whose conversation was characterized by frequent “collaborative” overlap. Stubbe (1998) also investigated the interplay of culture and gender with regard to interruptions. As noted earlier, she found that Pakehas exhibited and expected more listener feedback whereas Maoris were more comfortable with silence and with indirect or deferred feedback. However, when gender was folded into the analysis, she found that “both Maori and Pakeha women used a greater proportion of explicitly supportive feedback than men of either ethnicity” (1998: 284).

Thus researchers studying gendered patterns of overlap and interruption quickly observed that quantity could not be gauged without attention to quality. That is, a researcher must consider whether a second speaker overlaps in order to change the subject or disagree, or to support the original speaker. For example, Itakura and Tsui (2004) examined the conversations of previously unacquainted Japanese university students who were invited to talk to each other in eight cross-gender dyads. The authors were interested in features that previous studies had associated with dominance, including overlaps and interruptions. A quantitative analysis found no obvious pattern of male dominance. A qualitative analysis, however, did:

The male speakers tended to interrupt the female speakers when the female speakers started to present a contrary view, and they resumed their storytelling immediately following the interruptions. In contrast, the female speakers’ interruptions mostly supported the male speakers’ storytelling by way of clarification questions or addressee-oriented questions that encouraged the male speakers to elaborate on their story, or through comments on it.

(Itakura and Tsui 2004: 244)

Even the notion of “support” must be subject to qualitative scrutiny. Itakura and Tsui found, for example, that the women’s interruptions frequently took the form of self-denigration, wherein they represented themselves as having inferior knowledge and experience. When their male interlocutors supported their self-denigration, it reinforced the men’s dominance. Thus it’s not enough to count or even describe the purpose of interruptions. A researcher must also consider how interlocutors responded. In another example, the woman relinquished the floor when interrupted, but when she tried to interrupt a man, he didn’t. The result would not have been dominance if she had not relinquished the floor when interrupted – or if he had.

Finally, gender and language studies have highlighted the fundamental question, What is the meaning of interruption? In a study of postgraduate seminars in a Swedish university, Gunnarsson (1997) examined interruption patterns in three different disciplines. Though she found some inter-discipline differences (for example, men interrupted male presenters more than female presenters in humanities and natural science seminars, but women presenters were interrupted more in a social science seminar), she concluded, “The general tendency at all departments is that males interrupt more than females, but also that they are interrupted more, both by males and females.” Yet, she points out, both interrupting and being interrupted indicate that “men play the central role in the seminar discourse” (1997: 232). In other words, we cannot assume that being interrupted always indicates subordination.

In a survey of twenty-two prior studies, James and Clarke (1993) concluded that most found no significant gender differences in numbers of interruptions (though there was some indication that women’s overlaps were most likely to be for purposes of involvement and rapport). They suggested that the dearth of such studies might indicate that power relations are more significant than gender relations. Numerous researchers have sought to examine both gender and power in naturally occurring discourse. Menz and Al-Roubaie (2008), examining forty-eight doctor–patient interactions in Austria, found both power and gender to be significant. On one hand, physicians used more non-supportive interruptions than patients, and patients’ attempts to interrupt failed more often than physicians’, regardless of gender. At the same time, though, women – both doctors and patients – produced more supportive interruptions than men.

Bresnahan and Cai (1996) invited 260 undergraduates to listen to a tape while looking at a transcript of a conversation between a female faculty member and a male student, and then judge whether instances of simultaneous talk were interruptive. In addition, each subject took a test that measured “aggressiveness.” The researchers found that students, both male and female, who were judged to be aggressive were less likely to perceive simultaneous talk as interruptive – that is, attempts to dominate. Thus “aggressiveness” trumped gender in determining whether or not students rated simultaneous talk as interruptive. Nonetheless, the authors also found that women were more likely than men to judge “conflictual” simultaneous talk as interruptive and a violation of conversational cooperation. Furthermore, they found a difference in how women and men tended to regard potential responses to such interruptions. Men reported that they would respond to what they perceived as unwarranted interruption with retaliatory verbal responses, while women indicated that they disapproved of retaliatory verbal responses, regarding them as disruptive of conversational cooperation. Finally, gender trumped power in the conversation that subjects were asked to observe: the male student talked down to, interrupted, and even yelled at the female faculty member.

Putting aside the negative connotations of the term “aggressiveness,” Bresnahan and Cai’s findings bring us back to the importance of speakers’ conversational styles. Though the authors regard “aggressiveness” as an individual personality trait (which it no doubt can be), individuals’ verbal habits and ideologies can also be culturally mediated. The insight that one must take into account participants’ styles in order to interpret the meaning of their verbal behavior as well as their reactions to others’ verbal behavior has particularly important implications for intercultural communication.

Conclusion

When considering studies that seem to document such interactional intentions as inattentiveness, interruption, or dominance, it is crucial to bear in mind that effects may not reflect intentions. This is especially true for studies of intercultural communication, where differences in turn-taking styles may result in unequal access to the floor. Attributing observed patterns to the intentions of one participant simply recapitulates in research what is pervasive in daily interaction. Speakers tend to be unaware that turn-taking habits result in differing abilities. All speakers find it easy – indeed, automatic – to begin to speak at moments when it is routine to do so in their own speech communities. Thus those accustomed to turn-exchange systems that allow or favor overlap may automatically begin to speak while others are speaking – at the right moments, of course. However, speakers who have been acculturated in turn-exchange systems that eschew overlap will find it difficult to do so. I encountered amusing evidence of this when I was a guest on a radio talk show. A listener called in to complain about her husband’s unfair criticism. She said that following social occasions such as dinner parties, he often accused her of having dominated the conversation and prevented him from speaking. “He’s a big boy,” she said. “He can take the floor the same as I can.” Her husband, who was in earshot, called out, “You need a crowbar to get into those conversations.” Concluding that she had a high-involvement style while his was high-considerateness, I questioned her assumption that he was just as able as she was to take the floor. Because of their different styles, they had different capabilities with regard to turn-taking. She did not need a metaphorical crowbar because her high-involvement antennae had been sensitized over a lifetime of fast-paced, overlap-favoring conversation. He did, because his antennae were sending him signals ill suited to conversations in this style.

Exchanging turns is a fundamental and requisite element of human interaction. As is always the case with everyday behavior, when all goes well the mechanics of turn-taking operate without anyone paying much attention to them. But systems for achieving turn exchange are learned as children learn language, and they vary by language and culture. Therefore understanding turn-exchange and the nature of conversational floors is key to understanding intercultural communication, even as studies of cultural patterning have been key to understanding turn-taking and the nature of conversational floors in all human interaction.

NOTES

1 In my original study and subsequent essays based on it, I also take into account speakers’ ethnic backgrounds. My purpose in the present discussion is simply to illustrate potential effects of divergent turn-taking practices, so I have simplified my discussion by referring only to their regional backgrounds.

2 The audio recordings of the conversations I analyze in my original study (Tannen [1984] 2005), including those reproduced here, are available on my website: http://www9.georgetown.edu/faculty/tannend/CS%20Excerpts.html.

Transcription conventions are as follows:

3 Though it might at first seem contradictory, this observation is consonant with Watanabe’s finding, mentioned earlier, that in Japanese small-group discussions, the lower-ranking member spoke first. Like Yamada, Watanabe noted that Japanese participants regard holding the floor not as a privilege to be sought but a burden to be avoided. In the situation Yamada describes, a business organization, higher-ranking speakers take the floor not because they feel entitled to do so (as the American, Claire, perceives it), but rather because of a sense of responsibility that higher rank entails. This is reflected in Yamada’s phrase “share the burden.” Watanabe observed that “in all the Japanese group discussions, a female member started, followed by the other female member, then by the younger male member, and last by the oldest male member” (1997: 185). Rank, in other words, was determined by gender and age, categories which seem less likely to entail the responsibilities that accrue to professional rank in a business organization.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, Kristin J. and Campbell Leaper. 1998. Meta-analysis of gender effects on conversational interruption: Who, what, when, where, and how. Sex Roles 39(3/4), 225–52.

Bennett, Adrian. 1981. Interruptions and the interpretation of conversation. Discourse Processes 4(2), 171–88.

Besnier, Niko. 2009. Gossip and the Everyday Production of Politics. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Bresnahan, Mary I. and Deborah H. Cai. 1996. Gender and aggression in the recognition of interruption. Discourse Processes 21, 171–89.

Duranti, Alessandro. 1997. Polyphonic discourse: Overlapping in Samoan ceremonial settings. Text 17(3), 349–81.

Edelsky, Carole. 1981. Who’s got the floor? Language in Society 10,383–421. Reprinted in Deborah Tannen (ed.). 1993. Gender and Conversational Interaction. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. 189–227.

Erickson, Frederick. 1986. Listening and speaking. In Deborah Tannen (ed.). Languages and Linguistics: The Interdependence of Theory, Data, and Application. Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics 1985. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. 294–319.

Gardner, Rod and Ilana Mushin. 2007. Post-start-up overlap and disattentiveness in talk in a Garrwa community. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics. 30(3), 35.1–35.13.

Gunnarsson, Britt-Louise. 1997. Women and men in the academic discourse community. In Helga Kotthoff and Ruth Wodak (eds.). Communicating Gender in Context. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. 219–47.

Halmari, Helena. 1993. Intercultural business telephone conversations: A case of Finns vs. Anglo-Americans. Applied Linguistics 14(4), 408–30.

Hayashi, Reiko. 1988. Simultaneous talk – from the perspective of floor management of English and Japanese speakers. World Englishes 7(3), 269–88.

Itakura, Hiroko and Amy B. M. Tsui. 2004. Gender and conversational dominance in Japanese conversation. Language in Society 33(2), 223–48.

James, Deborah and Sandra Clarke. 1993. Women, men, and interruptions: A critical review. In Deborah Tannen (ed.). Gender and Conversational Interaction. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. 231–80.

Lehtonen, Jaakko and Kari Sajavaara. 1985. The silent Finn. In Deborah Tannen and Muriel Saville-Troike (eds.). Perspectives on Silence. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. 193–201.

Liao, Meizhen. 2009. A study of interruption in Chinese criminal courtroom discourse. Text and Talk 29(2), 175–99.

Maltz, Daniel N. and Ruth A. Borker. 1982. A cultural approach to male–female miscommunication. In John J. Gumperz (ed.). Language and Social Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 196–216.

Menz, Florian and Ali Al-Roubaie. 2008. Interruptions, status and gender in medical interviews: The harder you brake, the longer it takes. Discourse & Society 19(5), 645–66.

Moerman, Michael. 1987. Finding life in dry dust. In Talking Culture: Ethnography and Conversation Analysis. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. 19–30.

Murray, Stephen O. 1985. Toward a model of members’ methods for recognizing interruptions. Language in Society 13, 31–40.

Reisman, Karl. 1974. Contrapuntal conversations in an Antiguan village. In Richard Bauman and Joel Sherzer (eds.). Explorations in the Ethnography of Speaking. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 110–24.

Sacks, Harvey, Emanuel Schegloff, and Gail Jefferson. 1974. A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language 50, 696–735.

Scollon, Ron. 1982. The rhythmic integration of ordinary talk. In Deborah Tannen (ed.). Analyzing Discourse: Text and Talk. Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics 1981. Washington, DC: Georgetown University. 335–49.

Scollon, Ron. 1985. The machine stops: Silence in the metaphor of malfunction. In Deborah Tannen and Muriel Saville-Troike (eds.). Perspectives on Silence. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. 21–30.

Shultz, Jeffrey, Susan Florio, and Frederick Erickson. 1982. Where’s the floor? Aspects of the cultural organization of social relationships in communication at home and at school. In Perry Gilmore and Allan Glatthorn (eds.). Children In and Out of School: Ethnography and Education. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics. 88–123.

Sidnell, Jack. 2001. Conversational turn-taking in a Caribbean English Creole. Journal of Pragmatics 33, 1263–90.

Speicher, Barbara. 1993. Simultaneous talk: Parallel talk among Filipino-American students. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 14(5), 411–26.

Stivers, Tanya, N. J. Enfield, Penelope Brown, Christina Englert, Makoto Hayashi, Trine Heinemann, Gertie Hoymann, Federico Rossano, Jan Peter de Ruiter, Kyung-Eun Yoon, and Stephen C. Levinson. 2009. Universals and cultural variation in turn-taking in conversation. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106(26), 10,587–92.

Stubbe, Maria. 1998. “Are you listening?”: Cultural influences on the use of supportive verbal feedback in conversation. Journal of Pragmatics 29(3), 257–89.

Tannen, Deborah. 1981. New York Jewish conversational style. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 30, 133–49.

Tannen, Deborah. [1984] 2005. Conversational Style: Analyzing Talk among Friends. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Revised edition: New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Watanabe, Suwako. 1993. Cultural differences in framing: American and Japanese group discussions. In Deborah Tannen (ed.). Framing in Discourse. New York: Oxford University Press. 176–208.

Wells, Bill and Sarah MacFarlane. 1998. Prosody as an interactional resource: Turn-projection and overlap. Language and Speech 41(3–4), 265–94.

West, Candace. 1979. Against our will: Male interruption of females in cross-sex conversation. In Judith Orasanu, Mariam Slater, and Leonore Loeb Adler (eds.). Language, Sex and Gender. Annals of the New York Academy of Science 327. 81–100.

West, Candace and Don H. Zimmerman. 1983. Small insults: A study of interruptions in cross-sex conversations between unacquainted persons. In Barrie Thorne, Cheris Kramarae, and Nancy Henley (eds.). Language, Gender and Society. Rowley, MA: Newbury House. 103–17.

Yamada, Haru. 1997. Different Games, Different Rules: Why Americans and Japanese Misunderstand Each Other. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zuraidah, Mohd Don and Gerry Knowles. 2006. Prosody and turn-taking in Malay broadcast interviews. Journal of Pragmatics 38, 490–512.