CHAPTER

WHAT’S IN A MEME?

Meme. It’s that hot buzzword about which everyone in advertising, marketing, and communications with any digital sense can’t stop talking. Memes seem to arise spontaneously from the ether and from many sources at once. As much as the Internet likes fighting, all corners seem to genuinely agree on how they’re used—and, perhaps just as importantly, how they’re not used. Using a meme incorrectly is the digital equivalent of trying to say “Hello!” in a new language and accidentally calling someone’s mother a “ham planet.” If you’ve ever visited a community called r/AdviceAnimals, a shrine of the past era of meme culture still active on Reddit, you know that meme culture has very particular ways of using certain images, phrases, typefaces, backgrounds, and so on.

If you’ve ever dared post in r/AdviceAnimals without following its customs precisely, it’s safe to wager that you’ve felt the cold shunning of digital social faux pas. And unless you did some excavating yourself, you probably still don’t really understand where you went wrong. While to an outsider r/AdviceAnimals is just a collection of pictures with funny text on them, each particular background and corresponding caption follows a very particular structure and formula. So unless you’re lucky enough to innovate some new format that the community accepts, you’re speaking Mandarin in the middle of Mexico. And not like Chinatown in Mexico City either—you’re in Durango, and your phone is out of battery.

For advertisers and marketers, memes are those untouchable, invaluable relics that seem right within reach but crumble at our slightest touch. The truth is that very few of us really understand meme culture from the inside, and like any culture, it’s extremely difficult to fool the natives into thinking we’re locals. Fortunately for you, dear reader, I am a massive dork and am fluent in this culture. So as we say in the deep Internet, follow me, for I will be your guide.

We’re going to start at the very beginning with what is actually meant by the word meme. When we hear “meme,” most of us know what’s being discussed. A meme is one of those silly pictures or gifs with text on them. Right? Meme is one of those words that is widely used but rarely defined. Even in academic literature about memes—yes, there is academic literature about memes—researchers and authors rarely agree. In fact, the actual coining of the word meme tends to be a small footnote in most discussions about memes. Usually when we say “meme,” we mean a particularly popular piece of content with qualities of being highly shareable, of having repeated itself in various ways across time, and having particular rawness or lack of polish in the format of the content itself. One of the more prominent researchers on memes, a professor of digital culture named Limor Shifman, has gone as far as to list the specific qualities of memes, their types, what qualifies as a “meme” versus a “trend,” and much more.1 As wonderful as Shifman’s insights are into meme culture generally, Shifman and I disagree about one fundamental thing: the definition of the word. That’s right, you’ve just found yourself in the middle of a nerd war, so grab a keyboard and pick a side.

In 1976, an evolutionary biologist named Richard Dawkins wrote a monumental book called The Selfish Gene.2 This work was meant to articulate a modern understanding of the theory of evolution to people without a biology degree, and it’s still among the top recommended books about evolution. Because his audience consists mostly of nonbiologists, Dawkins takes specific measures to address what we might call a pop culture understanding of evolution. Most of us are probably familiar with the phrase “survival of the fittest.” Intuitively that sounds like it means “the plants and animals that are best equipped will survive the longest.” In actuality, Dawkins tells us we need to look a level deeper to understand the true meaning of the phrase. In keeping with the title of his book, Dawkins tells us that the “selfish gene” is the driving force of evolution, and its survival doesn’t necessarily mean staying alive.

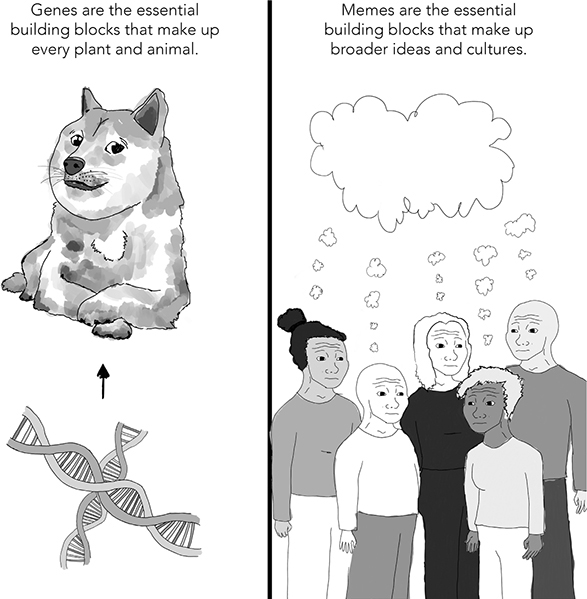

Genes are the most basic units of DNA, and all life on Earth shares the same building blocks of DNA arranged in different orders. The most important and mysterious quality of the gene is its ability to replicate itself. However, in the course of replication, genes sometimes make errors, which we call mutations. Most gene mutations aren’t beneficial and cause the new gene to die. But every so often, a useful mutation occurs, one that helps the new gene replicate itself more effectively and create a new generation of genes.

Imagine that one specific arrangement of DNA produces a kind of bird that survives by eating grubs that live in thick tree bark. As a whole, the population of birds will have an average beak length, but when you look at individual birds, they probably have slightly different-sized beaks. It may be the case that birds with slightly longer beaks tend to survive long enough to reach sexual maturity more often than birds with shorter beaks. Over the course of many, many generations of birds, we could predict that the average beak size will grow because the genes for longer beaks are better propagators than the genes for shorter beaks. If you can imagine a flip book of snapshots of each bird generation viewed in succession, it would almost appear that a conscious process was molding the birds’ beaks to be longer, which is a fascinating illusion created by the combined processes of random gene mutation and natural selection.

Dawkins’s broader point is that genes are the true drivers of the evolutionary process. The term natural selection is really a personification of nature “selecting” certain genes, when in actuality, nature and the environment simply present a set of circumstances in which particular mutations of genes survive, and others do not. We can lean into this metaphor as long as we remember that it’s an abstraction of the actual process.

In the spirit of personification, we could say that genes appear to be doing their best to make their ways into the next generations of genes. A few billion years ago in the “primordial soup” that made up the first accumulation of life-forms on Earth, simple genes replicated and spread throughout every environment they could manage. But energy sources are finite, and as genes thrived on Earth, the environment became more and more competitive. As genes continued to replicate themselves, some infidelities in copies helped these early genes adapt to new kinds of energy sources or survive in places that other genes couldn’t. Eventually, with generations and generations of replication and mutation, genes began to build around themselves what Dawkins calls “gene machines.” A gene machine is a plant or an animal—it’s a machine the gene builds around itself to help itself propagate a new generation of genes. (Don’t worry, I promise this comes back to memes.)

Following Dawkins’s model for genes and gene machines, Dawkins turns his focus to humans specifically. He acknowledges that something is clearly different in human evolution. In human evolution, Dawkins identifies a new kind of replicator—the meme, which he defines as a unit of cultural transmission. Things like ideas, songs, fashion, and language are all examples of memes—or, more specifically, groups of memes. Like genes, memes undergo an evolutionary process. When a new idea occurs to me, a physical process happens within my brain. And if I can find a way to articulate that idea to others, that physical process happens within their brains too. The recipient of my meme may even change the meme, akin to a mutation. So the meme isn’t just a metaphor. It’s not that ideas are like genes—they actually undergo a very similar process of replication, mutation, and exposure to selection pressures. The selection pressures imposed on a meme are complex, but they can be largely reduced to how attractive the meme is to other brains. Memes, like genes, don’t often exist in isolation, so the memes already encoded in our minds have significant influence on which new memes are appealing to us.

ANY IDEA WITH A CHANCE OF PROPAGATING IS A MEME

Let’s say I have an idea for a coffee shop that sells only lukewarm coffee. No hot coffee. No iced coffee. Just lukewarm coffee. That’s a meme (well, a set of memes)—a coffee shop that serves only lukewarm coffee. Now let’s say you and I are having a conversation, and I tell you about my idea. You might think to yourself, “Hmm, that’s a really bad idea. But what about a coffee shop that sells only iced coffee. . . .” In that case, a meme emerged in me, and I transmitted that idea to you. You received the meme, and in the environment of your brain—your personal meme pool—you evolved the meme. And let’s be honest, your evolved meme probably has a much better chance at propagating than my original. This is the process by which Dawkins claims all human culture is shared and formed over time. As ideas occur to us, we share them, and as ideas are shared, they evolve.

What started as a 12-page section in Dawkins’s book about evolutionary biology has become a set of disciplines entirely their own. The idea of “memes” as the new replicators caught fire in academia, and in that sense, the “meme” meme was an extremely successful propagator. However, one of Dawkins’s own success criteria for evaluating memes was “copy fidelity,” and in that sense, the “meme” was a bad meme.

Decades later, different schools of thought still debate what is meant by the word meme, and I bet you thought the next few paragraphs were going to drag you through the academic controversy surrounding the definition of memes. God, that sounds boring. Don’t worry, I wouldn’t do that to you. The only piece of that drama important to this discussion is how broadly we define memes. For Dawkins, a meme was a “unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation and replication.” The examples he uses are “tunes, ideas, catch-phrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches.” Susan Blackmore, another biologist who wrote a book called The Meme Machine, also defines memes as being any type of information that can be copied by imitation.3 This definition has been criticized for being too broad and, as Limor Shifman puts it, “may lack analytical power.” Shifman’s definition of a meme is much more specific and focuses more on the way the Internet colloquially uses the term meme. She calls memes “digital content units with common characteristics, created with awareness of each other, circulated, imitated, and transformed via the Internet by many users.”4 Catchy, isn’t it? To Shifman’s credit, she’s also called Internet memes the “postmodern folklore,” which is so true it hurts.

While I understand the criticism, I side with keeping the definition of meme very broad. For the purposes of this book, we’ll say that any idea that can be transmitted between brains is a meme. Even simpler—a meme is just an idea. When Dawkins gives examples of memes, he points exclusively to memes that have successfully propagated and spread. That makes sense because he’s driving home the point that successful memes spread like successful genes (Figure 1.1). Dawkins doesn’t dwell on those memes that aren’t successful propagators, so his focus on success has sometimes been interpreted to mean that only successful propagators are memes. If we return to the biological gene side of the metaphor, most genetic mutations are actually harmful and fail to help the mutated gene replicate. But those genes that fail to replicate are still genes. Likewise, most ideas don’t stick. But fortunately, we humans tend to have lots of ideas, and there are lots of humans, so we play a numbers game to continue evolving good ideas.

Figure 1.1 Genes Versus Memes

When we use meme as a reference to particular kinds of Internet content, we’re just isolating the most successful replicators. We’re also referring to more than just the idea when we talk about Internet memes—we’re including the format through which the idea is conveyed. For example, we might stumble upon the idea that budgets are generally tight for people right before they get paid by their employers. But it’s not an Internet meme until someone posts a photo of a goldfish cracker sitting on top of sushi rice next to a dab of wasabi and captions it, “When payday is still two days away.”5

In actuality, within that Internet meme is an entire complex of memes, and that’s true of nearly all memes. The simple fact that you can read this text means that not only have you mastered the English language and all of the necessary memes surrounding sentence structure and punctuation but you’re also familiar with the network of ideas communicated within each word. Technically, any individual meme we try to identify is a complex of memes networked together, so while we’ll continue to isolate particular ideas as individual memes, it’s worth remembering that memes rely on a broad cultural net of other memes for context. Our language, cultural knowledge, education, and personal experience all influence how we process memes.

As brands, everything we do revolves around memes. Beyond that, a brand itself is a meme—or a combination of memes. After all, a meme is just an idea. As advertisers, communicators, community managers, influencers—whatever we want to call ourselves—we’re in the business of propagating memes. Whether it’s “Just do it,” “I’m lovin’ it,” or “Buy my merch, you schmuck,” ideas are at the bottom of every marketing and communications discipline. When we talk about Internet memes as “those silly pictures with text on them,” what we’re really talking about is the format used to communicate different memes.

In following from Dawkins’s gene and gene machine framework, we might call these formats “meme machines.” For early humans, we had only the meme machines of the sounds we made, the pictures we drew, and then eventually, the languages we invented. Now, as you’re reading this, you’re (hopefully) extracting memes from this book, and the meme machine is likely the physical pages in your hand, the digital screen on which the text is being displayed, or the audiobook version to which you’re listening.

MEME MACHINES EVOLVE TO MOST EFFICIENTLY COMMUNICATE THEIR MEMES

Let’s break this down a little more using a favorite example of mine, particularly for those of us with nine-to-fives. Let’s talk about the meme “Mondays suck.” Inevitably, embedded within the meme “Mondays suck” is an endless thread of more granular memes. To understand what is meant by these two words, we need to understand what Mondays are and the structure of a week. We need to understand the colloquial definition of the word suck, and we also need to understand the general cultural phenomenon of the average workweek starting on Mondays. We can continue to excavate more and more granular memes embedded in this phrase, but let’s assume we all understand what that means. Mondays suck!

In fact, “Mondays” have sucked for a very long time. Marcus Aurelius even dedicates a section of Meditations to how awful “Mondays” are:

At dawn, when you have trouble getting out of bed, tell yourself: “I have to go to work—as a human being. What do I have to complain of, if I’m going to do what I was born for—the things I was brought into the world to do? Or is this what I was created for? To huddle under the blankets and stay warm?6

There are entire movies written about how much Mondays suck. Office Space is a personal favorite. The movie came out in 1999, and today the only things that really feel dated about it are the fashion, the cubicles, and the film quality. In Office Space, the protagonist Peter can’t seem to deal with yet another Monday. He hates his job, and Mondays represent the beginning of his wretched workweek. Perhaps the pinnacle scene demonstrating Peter’s hatred for Mondays happens early in the film as he approaches the cubicles of two friends in an attempt to lure them out to lunch early. A colleague sneaks up behind him and, in the cheesiest “office joke” voice possible, says, “Sounds like somebody’s got a case of the Mondays.” Peter cringes. His friends cringe. We cringe. The only thing worse than Mondays is clichéd office humor about Mondays. But somehow, millions of people enjoy watching Office Space, which at its core, is an hour and a half of jokes about how much Mondays suck. Why?

The meme machine is just as important as the meme itself. The meme can be carried by two entirely different meme machines, and they may show absolutely polar results when we measure their effectiveness at propagating. Great comedians are perfect examples of this principle. A great comedian can tell you a joke about something you’ve heard a thousand other jokes about but will do so in a way that makes the idea—the meme—feel totally fresh and new. A bad joke teller can start with the most hilarious possible content and absolutely fail to engage an audience.

When we’re participating in social media as content creators, we desperately need to understand this principle. In advertising and marketing, we generally spend an enormous amount of time thinking about what we want to say—the meme—but we rarely put equal thought into the meme machines we use to deliver those memes. We have particular formats that tend to be the norms of our industry—60-second, 30-second, 15-second, and now even 6-second cuts of video—and we force our memes to fit into those machines. Video can be the right meme machine to deliver a meme, but it isn’t always.

Imagine I’m at a friend’s house for movie night, and that friend presents me with a few choices in movies to watch. One of those movies happens to be Office Space, and because I like that movie, there’s a strong likelihood that I’ll pick it. So in the context of a group of movies—a meme pool of movies—Office Space is a viable meme carrier for people like me. But we don’t always encounter meme machines in their original environments.

If I’m scrolling through a cable TV menu, and I see that Office Space is on but halfway over, I probably won’t tune in to watch. OK, maybe for like five minutes. In the slightly more competitive meme pool of cable TV menus, Office Space has the disadvantage of being much longer than an average TV program. But if I love the movie, there’s still a chance that I’ll tune in anyway.

Now imagine that the movie Office Space is sitting in its full length on my Facebook feed. Even if I’m the biggest Office Space fan in the world—and I might be by the time I’m done with this paragraph—the likelihood that I’ll sit and watch for an hour and a half is pretty low. Maybe even zero. Why? Because Facebook—and social media feeds in general—are more competitive content environments. Social feeds are algorithmically programmed to deliver more and more interesting content, and they get better over time as they gather engagement data about the stuff with which you’re most likely to interact.

This isn’t to say that the meme of “Mondays suck!” can’t propagate successfully in social feeds though. Remember that Office Space is just one of many meme machines that can carry the idea that “Mondays suck!” We know for a fact that our “Mondays suck!” meme can and does propagate in social because there are myriad examples of Internet memes, jokes, videos, and so on that carry similar memes. It’s just that the meme machine needs to evolve to survive in these more competitive environments.

A movie is a relatively heavy meme machine. A movie requires that we give our full attention to something for at least an hour and a half. In order to fully absorb the memes from the movie, we not only need to give it our full visual attention but our full auditory attention too. Then, even after we’ve given our captive visual and auditory attention, we’re in a passive state of waiting for the memes to be delivered to us. We don’t dictate the speed at which the movie plays, and in a world where more and more media is consumed on mobile devices, we can hardly expect to have a few seconds of undivided attention, let alone a couple of hours. In order for these memes to thrive in a social environment, they must find a way to become lighter. The meme machines we use must be low friction and must be extremely efficient at delivering their memes.

One way the Internet organically evolves meme machines to become lighter is to take a video with spoken dialogue and turn that scene into a screenshot with a caption on it. Suddenly, the meme machine goes from passive to active. When the meme is contained in an image-with-text-on-it meme machine—an image macro—we consumers of the content suddenly become active participants in the extraction of the meme. We read through the text, which we process more quickly than when we hear something out loud, we extract the meme from the meme machine, and we continue scrolling through our feeds.

We don’t have to enable sound on our phone or put headphones in or click a full-screen button to watch something. We just read and move on to the next things in our feed. Not only that, an image with legible text on it is extremely easy to share. Have you ever seen a funny video in a social feed and wanted to send it to someone who wasn’t connected to you on that social network? It’s almost impossible for the average person. But if you’re trying to share an image, you have a greater ability to save it to your local device or even take a screenshot. Screenshotting an image preserves the meme, while screenshotting a video usually loses the original meme. That’s in large part why efficiency is such an important driver of sharing online—the lightness of a meme machine is an important determinant of how well the meme it carries can propagate. The meme machine is vital to the meme’s survival.

THE MEME MACHINE IS AS IMPORTANT AS THE MEME ITSELF

There is a particular kind of meme machine that dominated Internet meme culture during the late 2000s and early 2010s. Those of you who browsed Reddit or 4chan regularly probably already know where this is going. The Internet collectively agreed on Impact font as the universal meme font. But not just Impact font—white Impact font with a black outline.

The consistency in the use of this font and format for memes is striking when we look back through this period of meme culture. And it’s no accident. Impact font is particularly thick, and it stands up to even chaotic imagery. Combined with a black outline, this font is legible on nearly any kind of background. Not only that, when this format was screenshotted and lost resolution, Impact generally stood up to the image degradation. The meme was still extractable. In some sense, we could say that this font style was evolved for the ultimate efficiency of the meme machine. A large, clear font that helps to deliver a meme more efficiently is a helpful trait for the survival of the meme it carries.

Very few brands leverage this meme machine, and I think the reason for that is summed up nicely in a piece of feedback I once received from an art director I worked with: “But it’s ugly!” It’s not an unfair critique, and I don’t disagree—white Impact font with a black outline isn’t exactly chic. But the problem with the pretty work our industry tends to love is that it’s rarely efficient at delivering our memes. Small text is usually prettier than large text. Low-contrast text is also a trend that comes and goes in ads. Nonstandard fonts are usually fun ways to express brand personality, but they often reduce the legibility of the content slightly. If you’ve worked in an agency with a creative team, you’ve probably witnessed the “wall exercise” where we put all of our creative work up on a wall for a holistic review. In these settings, as we focus specifically on our work in isolation, we might be able to convince ourselves that our swirly white font on our light pink background is plenty legible. We can read it. The problem is that we’re not talking about if someone can read it. We’re talking about whether or not someone will read it. According to Facebook, people on mobile spend an average of 1.7 seconds per piece of content.7 So even if that fancy font takes just half a second more to read, that’s 30 percent of the overall attention we get from the user spent trying to extract the meme without even processing it. Efficiency of communication is absolutely pivotal to successful meme sharing in social feeds.

Part of the challenge of driving sharing and engagement in social is identifying the most optimal meme machine to carry our memes. Imagine that we’re biologists tasked with engineering a glow-in-the-dark frog that has a reasonable chance of surviving in a particular environment. We have two potential paths. In the first, we try to write frog DNA from scratch. Suspending disbelief just a little, let’s imagine that we can actually do that. We conduct research on a bunch of different frogs, write our own DNA sequence based on that research, and we embed some glow-in-the-dark genes. The trouble with this path is that exactly how genes interact with one another and their environments isn’t always obvious to us in a lab. What may seem like an arbitrary feature could actually be pivotal to some overlooked aspect of our frog’s survival, or it may affect other important genes in a way that isn’t immediately obvious.

The second path we might pursue is to take a frog out of the environment in which it needs to survive and insert our glow-in-the-dark DNA into its otherwise naturally evolved genetic code. By doing so, we harness the evolutionary process to our advantage rather than trying to re-create it in a lab setting.

The same strategy works for memes. Minus the frogs. Actually, scratch that, frogs included. (This one’s for you, Pepe. I’m sorry you got hijacked by white supremacists. You were a good meme.) This is a lesson we need to learn as social advertisers. When we evaluate an ecosystem—a social network—and want to find a way for our memes to survive and thrive, it’s important for us to understand what content is organically successful at propagating in that environment. While as an industry we pay lip service to the idea that we want our content to feel “native to the channel,” our creative reviews rarely compare the content we’ve made for our brands to the content that organically drives sharing. More often, we compare ourselves to our competitors, and they’re usually no more native to the environment than we are.

This isn’t to say that every brand should go try to force its latest product messaging into the Drake meme format. It’s not uncommon for influencers in advertising and marketing to talk about “hijacking” memes by inserting themselves indelicately into the latest hashtag or Internet meme. Brands that do so without adding value usually show up in communities dedicated to poking fun at them. Internet meme culture is very particular, and not every brand can or should engage with Internet meme culture. Whether or not we aspire to participate in meme culture, we still have much to gain by taking the frog out of its environment and trying to figure out what makes it work. The meme machines that evolve within meme culture are evolutionary products, and regardless of whether we find the memes embedded in them particularly relevant, if a meme machine is effective at propagating, it has a lesson to teach us.

As nonsensical, ludicrous, and even offensive as Internet meme culture can sometimes be, it can teach us valuable principles in creating share-driving content—from the way its meme machines are made, to memes’ physical characteristics, to the point of view from which the memes are delivered. Every day, kids with old versions of Photoshop on their parents’ computers manage to create content that engages millions of people. And if they can do it, our armies of professional designers, photographers, copywriters, strategists, marketing professionals, communications specialists, and community managers can too. We can create engaging content that drives pass-along—or, in the very least, that efficiently delivers our messages.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

• A meme in the traditional, biological sense is simply a “unit of idea” or a “unit of culture.”

• A meme machine is the format used to communicate an idea or meme.

• In order for our brand messages (memes) to effectively drive engagement, we should express them in the lightest, most accessible formats (meme machines).

• Successful meme machines vary widely among different kinds of social networks. Ask yourself, “What types of content and formats are organically successful in this social network?”