CHAPTER

WEARING OUR MEMES

The Ideal Self, Managed Self, and True Self

In 2014, a Dutch graphic design student named Zilla van den Born took a five-week vacation to Southeast Asia.1 As millennials often did in 2014, Born chronicled her vacation on her Facebook profile. She posted what’s become standard issue vacation content—photos of exotic-looking foods, the fancy entrance to her hotel, a photo of herself sitting next to a monk in a Buddhist temple, and an action shot snorkeling with tropical fish. It looked like the kind of vacation to which any college-aged student aspires—a foreign country, new experiences, idyllic photos, and the social capital that follows from posting about each of those. After her vacation was over, Born shared something shocking. She never actually left town.

Her meals were shot in local Thai restaurants. She decorated her bedroom to look like a hotel entrance using some sheets and Christmas lights. The Buddhist temple was actually in Amsterdam where she lived. She snorkeled in the pool at her apartment complex and added some tropical-looking fish to the background—really putting that graphic design degree to use. Born’s misadventure caught international attention, and when asked why she went to the trouble of faking a vacation, she said, “I did this to show people that we filter and manipulate what we show on social media and that we create an online world which reality can no longer meet. My goal was to prove how common and easy it is to distort reality. But we often overlook the fact that we manipulate reality also in our own lives.”

There is a popular notion that social media brings out the braggarts within each of us—that we’re seizing the opportunity to mislead our family, friends, and followers into thinking our lives are better than they are. That’s an awfully sinister outlook on humanity, and I don’t think it’s quite so insidious, even if social media does distort reality. Social networks are structured to give us room to express ourselves in various ways. For many social networks, that means we create a profile that corresponds with our real-life identities—we use our real names, we share actual photos of ourselves and our lives, and we connect with people we know.

When we’re presented with such a structure, it’s natural that what we gravitate toward posting are highlights of our lives. In lieu of the physical characteristics that define us in our offline lives, we have only the memes we share to define ourselves. The memes we wear in social networks—the things we say, the content we post, the videos we share—are akin to digital clothing. We may not always make an extremely intentional, conscious choice about them, but our memes define us to our social groups. The social media profiles in which we’re unabashedly our offline selves act as catalogs of our lives, so it’s natural that we curate positive moments, meaningful memories, and other pieces of content and culture that we want to define us.

Even if this highlight reel effect isn’t intentional on our parts, there are real psychological consequences to seeing the world through such a filter. Many psychologists believe there is a demonstrable, causal link between heavy social media usage and anxiety and depression.2 While that may strike us as overly alarmist, it’s worth noting that social media is brand new in the human timeline. Evolutionary biologists estimate that modern humans have been around for 260,000 to 350,000 years.3 Social media has existed for about 20. If the entirety of human existence were a movie, social media would get about half a second of screen time. Our brains—and the mechanisms we evolved to interact socially—are not accustomed to this new phenomenon.

The Internet is overwhelming for the social parts of our brains. For most of human existence, we lived in tribes of 100 to 250 people, and correspondingly, anthropologists estimate that the average number of “stable relationships” we can maintain is about 150—often referred to as Dunbar’s number.4 In studying different primates’ social lives, anthropologist Robin Dunbar discovered a correlation between the brain size of a primate and the average size of that primate’s social groups—spoiler, humans have the biggest primate brains and maintain the highest number of stable relationships. This isn’t to say that the average person can only remember 150 people. As Dunbar put it, this is “the number of people you would not feel embarrassed about joining uninvited for a drink if you happened to bump into them at a bar.” If that’s really the definition of a stable relationship, my number is more like 2, and one of those is my cat (love you, Matilda).

Compare Dunbar’s number to the average Facebook profile in 2016, which had 155 friend connections.5 The average social media user in 2018 also maintained eight different social media profiles across different sites.6 It’s not hard to see that we’re stretching our social cognitive ability far beyond its limits. We have many more “friends” than we have friends. Particularly when we’re using a social platform in which we’re identified by our driver’s license name, we’re doing the evolutionary equivalent of peeking through our window at our neighbors. At least, that’s how our brains are wired to think. We get glimpses into the lives of our connections, and thanks to the aforementioned tendency for us to use these channels to curate highlights, we find ourselves in a difficult conundrum.

Consciously or not, when we’re evaluating ourselves in social media, we’re comparing our complex lives full of ups, downs, and in-betweens to other people’s highlight reels. Evolutionarily, we’re trained to evaluate ourselves against our neighbors because we may learn useful information that way. If our neighbor is much more successful at growing crops than we are, it’s useful for us to peek over to see what he or she is doing differently. Or, more accurately in evolutionary terms, the people who peeked over to see how their neighbors were growing crops were more likely to survive than those who didn’t.

People with more social awareness are better in tune with their groups, and humans’ tendency toward sociability is credited as an important trait for giving us competitive advantage over predators and other primates. Our close evolutionary relatives, the Neanderthals, were stronger than humans, evolved tools earlier than humans, and had larger brains than humans. But a prevailing theory of why the Neanderthals went extinct about 40,000 years ago revolves around the human capacity for sociability and coordination. Some researchers even suggest that human domestication of wolves—arguably an aspect of interspecial sociability—also played an important role in giving them the edge over Neanderthals.7 We’re acutely aware of our broader communities and how we fit into them—it’s a fundamental part of how we think.

So when social media gives us this new window into the lives of our neighbors, and those neighbors exclusively post their life highlights, it’s easy for us to conclude that we’re less successful, less attractive, less happy, and so on. Ironically, being constantly exposed to these highlights has demonstrably negative effects on our mental health. Depression in young people has risen by as much as 70 percent in the past 25 years according to a recent study in the United Kingdom, and some researchers point to social media as the cause.8, 9 The same study showed that 63 percent of Instagram users reported feeling miserable after using the platform, higher than any other social media site.10 This study got something right that many social media studies don’t—it stratified the effects of different social platforms.

There is a growing body of research about how social media affects mental health, but many of these studies lump every website or app with a feed into the category of “social media.” How social media affects our brains is an extremely important territory for research, but nuanced differences in social network structures manifest significant differences in user behaviors and mindsets. In fact, one study conducted by the University of Utah showed that people with serious mental disorders—bipolar, schizophrenia, and depression—improved as they participated in Reddit communities about those topics.11 By analyzing linguistic dimensions like positive emotion, negative emotion, and sadness, researchers observed that the language subjects used improved significantly in 9 out of 10 categories over a seven-year period. Depressed people who participated in the r/Depression community became less depressed.

How could a community full of depressed people spark such drastic improvements in positive emotion while social networks full of positivity and beauty like Instagram cause users to feel depressed? My theory is that the actual content in a social feed is only a small part of that equation. What’s more important is the mindset of the people browsing that feed and their relationship to the memes with which they’re interacting. While there is a wide range of variables that differentiates social platforms from one another, two are critical predictors of user mindset: one, how users are identified in a social network, and two, how they’re connected to other people. These factors not only determine user mindset but dictate what types of memes resonate with them. In marketing, we tend to talk about how Facebook users are different from Twitter users who are different from LinkedIn users. But we often gloss over the fact that when we talk about a Facebook user, a Twitter user, and a LinkedIn user, we may very well be talking about the same human behind the screen. The differences between these spaces are psychological—they’re not often separate populations of people. Most people on 4chan probably have Facebook accounts. They just act very differently on 4chan. Or most of them do, anyway.

IDENTITY AND SOCIAL CONNECTIONS SHAPE ONLINE MINDSETS

Simply by looking at these two variables of user identity and connection, we can create a model that accounts for the broad diversity of user mindsets and behaviors across the Internet. Let’s start with online identity. The ways in which we’re identified online tend toward one of two categories: either we identify as our offline selves, or we participate anonymously. If we’re using our driver’s license name, sharing photos of ourselves, and generally behaving in ways that feel—to us—to be consistent with how people know us offline, we’re identifying as our offline selves.

Anonymity can be a little more complex because there are different ways in which we can be “anonymous.” On 4chan, we’re truly anonymous—we have no usernames or identifying information corresponding with our posts. In video games, online forums, and platforms like Reddit, we tend to participate pseudonymously—we create usernames that might be considered alternate personas for ourselves but that we tend to wear for extended periods of time. On platforms like Blind, an app that allows for “anonymous” discourse between people within particular companies or organizations, we again create usernames unrelated to our actual names, but we have an added layer of context that everyone with whom we’re interacting is part of our organization. While anonymity does tend to stratify in nuanced different ways, anonymity offers a consistent value to users—freedom.

The second key factor for understanding how mindsets change between social networks is how people are connected to one another. On networks like Facebook and Snapchat, we’re generally only connected to the people we know offline. On networks like Instagram and Twitter, we may have many of the same friend connections as we do on Facebook, but with a twist. We also have the ability to connect with a plethora of people we don’t know through mechanisms like hashtags and content discovery. Finally, on networks like Reddit, we’re not organized around our offline connections at all—rather, we’re connected through shared interests, ideas, or passions.

These different ways in which we’re connected to people can completely transform our behavior and can determine the types of memes that will resonate with us. The types of memes with which a person might engage in anonymous space may be completely different from the memes that might resonate with them in spaces in which they present their offline selves. As advertisers and communicators, we may be reaching the exact right people in the exact wrong place—or we may find that a little reframing of our message to suit these different spaces drives orders of magnitude better resonance.

IN FREUD’S MODEL, THE MIND IS COMPOSED OF THE ID, EGO, AND SUPEREGO

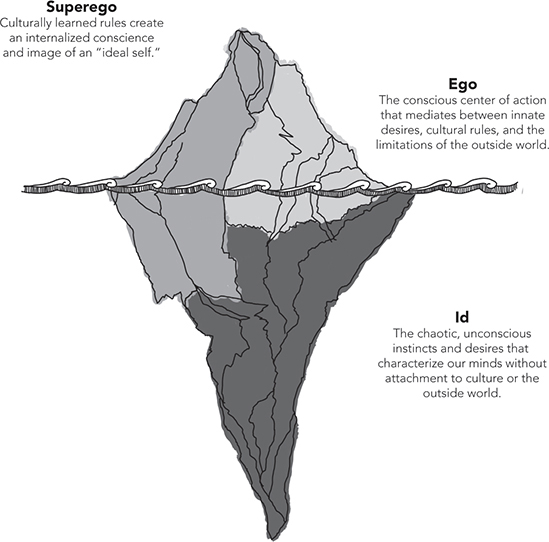

The intersection between these two fundamental elements of social network structure net a model that’s likely to be strangely familiar to students of psychology. In his book Civilization and Its Discontents, Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, proposed a model of the mind often represented by an iceberg (Figure 4.1). Just as 90 percent of an iceberg is submerged beneath the waterline, Freud contended that 90 percent of the workings of a person’s mind is unconscious. Before Freud, most people didn’t believe there was such a thing as subconscious thought. In what was then a radical idea, Freud proposed that a single mind is actually composed of different, sometimes incompatible psychological forces. Freud called our mostly unconscious, unfiltered, instinctual drives and desires our Ids. As social creatures living in complex societies, we also internalize our learned cultural rules, which becomes our conscience and resides in what Freud called our Superegos. And to mediate between our instinctual desires, our cultural ideals, and the limitations placed on us by the physical world, we develop what Freud called our Egos.

Figure 4.1 Freudian Iceberg

While modern psychology isn’t particularly kind to Freud, his ideas changed the world and how we understood ourselves in it. Not only was the concept of an “unconscious mind” considered ludicrous prior to his writing, but Freud is also credited with pioneering therapy as a practice—“the talking cure,” as he called it.12 Freud was the first to coin the term “Ego,” Latin for “I,” which we now use to describe the self-conscious aspects of ourselves. In the words of evolutionary psychologist Dr. Jordan B. Peterson: “Freud established the field of psychoanalysis, and with it, rigorous investigation into the contents of the unconscious. Modern psychologists like to denigrate Freud, and I think there’s a reason for that. Freud’s fundamental insights were so valuable and so profound that they got immediately absorbed into our culture, and now they seem self-evident so all that’s left of Freud are his errors.”13

Freud’s model remains unique in that unlike much of modern psychology and neuroanatomy, he intended to represent the mind rather than the brain. The components of Freud’s model—the Id, Ego, and Superego—correspond to different phases of mental development and the resulting psychological forces. The Id is the instinct-based, chaotic, generally unconscious mind with which we’re born. As infants, we exist solely as Id—we’re driven by instincts and desires without any real sense of “self” as being separate from the world. The Ego forms as the desires of the Id meet the limitations placed on us by the real world. As we begin to form a sense of self that is clearly differentiated from the outside world, our Ego becomes our conscious center of action. The Superego is our final layer of development and embodies our culturally learned rules. Within the Superego exists a vision of our ideal self and our conscience. Our conscience measures the actions of our Ego against this embodiment of an ideal self, based on what we’ve learned constitutes a good person. When we fail to act in accordance with our ideal self, we feel guilt. The instinctual desires of our Id and the cultural rules in our Superego are often in conflict, with our Ego in a constant state of moderation between the two.

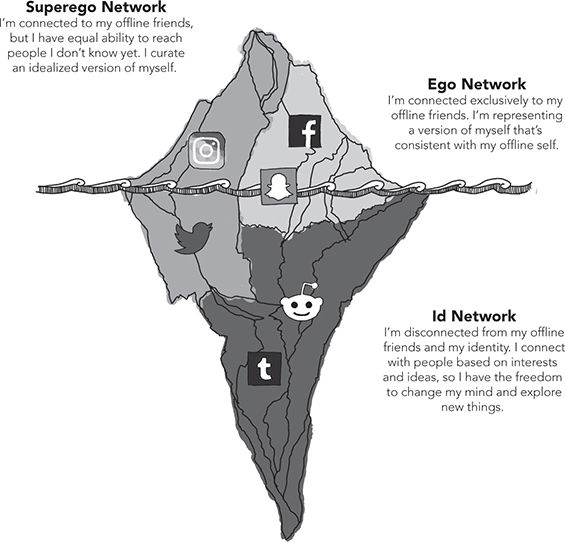

THE ID, EGO, AND SUPEREGO MANIFEST THEMSELVES IN DIFFERENT KINDS OF SOCIAL NETWORKS

We tend to occupy one of three essential personas when we interact online, and these personas correlate to this Freudian structure. Which type of persona we wear is closely related to the two factors of social network structure: how we’re identified and how we’re connected. When we engage as our offline selves and are connected exclusively to the people we know offline, as we do on Facebook and Snapchat, we’re manifesting our Egos—managed versions of ourselves (Figure 4.2). We pay close attention to how we communicate about ourselves because anything we say or do has a one-to-one correspondence with how people will think about us offline. We engage with content and interests that we’re comfortable wearing publicly for all of our friends to see, and for good reason. Most of us know that even so much as liking a post on Facebook has potential to create a story in our friends’ feeds, so anything and everything we do in that space is on public display. We know that posting something controversial or offensive in a managed self network is akin to shouting it at a family reunion or at a bar with our friends.

Figure 4.2 Social Media Iceberg

We’re also aware that our audiences—the friends with whom we’re connected—have particular tastes, ideologies, opinions, and so on. We know which kinds of posts have generated positive feedback in the past and which haven’t. We like likes. Ego networks also tend to curate feeds that are particular to us—nobody else in the world has the same feed as we do. We’re in a mode of self-representation in Ego space, but instead of wearing our favorite bands’ T-shirts, we like our favorite bands’ posts. Instead of a political bumper sticker on our car, we share our candidates’ fundraisers. We don’t tell our network the story of our vacation. We post pictures and tag our friends. We’re solidifying our identity online for the people we know offline.

On platforms like Twitter and Instagram, we’re again likely to participate as our offline selves, but there is a significant mindset change that comes from being potentially exposed to millions of people we don’t know. It’s the difference between recording a silly selfie video you’d send to your friends and a video that might just get broadcast on national television. This is Superego, ideal self space, where we may have the exact same friend connections we did on Facebook, but where we’re discoverable by the seemingly infinite number of people we don’t know yet. In ideal self space, we filter our selves a little more, we try to be a little quippier, and we tend to curate particularly bright highlights. Our Facebook friends may well know that it rained for five out of six days on our trip to Hawaii, but that won’t stop us from posting a glamorous beach photo on Instagram as our vacation recap.

Superego networks are often hierarchical. Social standing means everything. Follower counts, post engagements, trendy profile pictures, and influential retweets are primary markers for where we stand in the social hierarchy. In many Superego, ideal self networks, we don’t even have friends—we have followers. These one-way relationships foster a different kind of emergent self-representation. Unlike Ego networks in which we’re bound exclusively to the people who know us offline, in Superego space, we owe it to our followers to represent ourselves in ways that are compelling and interesting, even if that means embellishing at times. We’re social mercenaries, following the people with whom we want to associate and hoping that those we don’t will follow us anyway.

This isn’t to say that every account on Twitter or Instagram is a manifestation of someone’s ideal self. When we’re dealing with such ultracomplex topics as personal identity, we’re looking for general similarities among average users. Twitter and Instagram also host significant representations of meme culture, online trolling, interest-based conversations, and other trademarks of the anonymous web. This has to do with individual variability and site functionality. Technically, we can be anonymous on Facebook too, but because Facebook requires friend connections to make use of the vast majority of its functionality, anonymous Facebook users just don’t have much to do. Anonymous Twitter and Instagram users, however, have plenty of room to join conversations, mobilize trends, stir up drama, and so on. We might even consider trolls on Twitter and Instagram more problematic than trolls in anonymous space because the playing field isn’t exactly level. When 4chan users jab back and forth with offensive insults, both parties are anonymous and so have an equal stake in the outcome—very little, if they know what’s good for them. Anonymous trolls on Twitter have an endless stream of opportunities to interact with people who have invested some or all of their identity in their handles.

While anonymity has certainly borne the brunt of much of the discourse about online safety, anonymous space can be extremely constructive and healthy for people. Without an offline self to represent, people are free to be expressive and candid. This unfiltered self is an embodiment of the Id. Id networks are those in which users are disconnected from their offline selves and are organized around their interests and passions rather than by their offline connections. Networks like Reddit, Tumblr, Imgur, Twitch, and even 4chan are examples of Id networks wherein people are more free to express themselves, explore new ideas and interests they’re not ready to wear in the offline world (yet), and discover communities filled with people of similar interests.

On Id networks, we’re looking for content that’s funny, compelling, entertaining, or otherwise interesting to us—not representative versions of ourselves. We’re able to discuss taboo topics without worrying about what our friends and relatives might think. We have the freedom to explore new hobbies and topics that pique our interest but that aren’t necessarily things we’d use to represent ourselves to others. We’re in a state referred to by some psychologists as epistemic curiosity—a pleasurable state of curiosity with anticipation for reward.14 The “reward” we receive is when we learn something new or stumble across content that’s entertaining and novel that we didn’t necessarily expect.

Unlike Ego and Superego networks, Id networks tend to prioritize communal feeds over individual ones. On platforms like 4chan, there is no custom feed provided to individual users—individuals simply browse boards that serve the latest posts of fellow community members. Reddit provides users with a Home feed that is customized based on the communities of which a user is part. While that feed is customized to particular users, its contents are dependent on community voting, not individual profiles. Reddit’s fundamental structure lies in its communities, which display the same content to all members.

These shared experiences generate a sense of community that truly differentiates Id networks from other social media platforms. Counterintuitive as it may seem, anonymous Reddit users feel deeply connected to one another and the platform they share in ways that users in identity-based networks usually don’t. People on Reddit describe themselves as “Redditors” in a way that Facebook users never identify themselves as “Facebookers.” This community sensibility enables constructive, nuanced conversations among people of very different perspectives, and because users are disconnected from their offline identities, they are generally more open-minded to new ideas and information. It’s easier to change your mind when no one is looking.

For those unfamiliar with Reddit, it is truly a marvel of online community structure. Not only does the broader Reddit platform identify as a community, but Reddit can also be characterized as a network of individual communities called “subreddits,” which fly under the Reddit flag. Each community on Reddit is staffed by a team of volunteer moderators, and those moderators create and enforce rules specific to each community, such as what can and cannot be posted, how to title posts, how to behave, and what kinds of information are off limits. As one Redditor put it, “I add ‘reddit’ after every question I search on Google because I trust you all more than other strangers.”15 That post generated over 35,000 net upvotes and remains a top post in the r/ShowerThoughts community. For reference, a “shower thought” is described by the community as “those miniature epiphanies you have that highlight the oddities within the familiar.”

Granted, the anonymous Internet has its thorns too. Like communities offline, online communities can be problematic. Questionable behavior in anonymous, community-based Id networks often manifests in very different ways than in identity-based Ego or Superego networks. While fake news stories now plague identity-based social networks, anonymous communities tend to be more resilient, thanks to the communal nature of Id network conversations. However, when an undesirable idea catches on in an Id network community, it also has the potential to mobilize at a broader scale and with more velocity than in identity-based networks. When a number of celebrities’ private, nude photos were leaked in 2014, an event dubbed by the Internet as “The Fappening,” people posted about the leaks on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and just about every other identity-based social network.16 But it was 4chan that originally popularized the images, and a Reddit community called r/TheFappening soon became a hub of activity, conversation, and content sharing about the event. The r/TheFappening community has since been banned, but the coordination of Id networks enabled these leaked photos to trend at a much broader scale than if they’d been limited to identity-based networks alone.

The social media ecosystem is vast and complex. The rallying cry leveled against social media users’ “mindless consumption” has become a caricature of itself. Social media isn’t simple, and neither are the driving forces that compel us to participate. While it can certainly be addictive, social media is driven by our deeply rooted nature as social creatures. The average social media user maintained 8.5 different profiles across different websites in 2018, and that number rose from 8 in 2017 and 7.6 in 2016.17 Were social media simply a vehicle for mindless consumption, we’d expect social media profiles to consolidate, but the opposite is happening. Why? Different social network structures satisfy different social and psychological needs for us. Ego networks allow us to solidify our connections to our tribes and define ourselves to the group of people who know our offline selves. Superego networks allow us to express the selves we one day hope to be—the selves we most want to represent to the world—and to peer into the ideal selves of others. Id networks give us license to explore new territory, try on new ideas and interests, and form bonds with those who share our passions.

In the following chapters, we’ll dig further into Id, Ego, and Superego network structures, what makes them tick, and how brands are leaning strategically into the value people derive from participating in each. In Part I, I noted that adding value should be our top concern as marketers building brands in social media. I also mentioned that, while simple, the problem with adding value for people in social media is that different social networks provide different kinds of value. By examining these different essential mindsets for social media users, we’ll begin to understand exactly how we can add true value to these vastly different online spaces. We’ll be better equipped to find our niche and build scalable, strategic campaigns that generate engagement with our audiences in ways that feel natural and native to the space. We’ll explore examples of brand engagement, campaigns ranging from the iconic Wendy’s Twitter account to Charles Schwab on Reddit to how Squatty Potty got people on Facebook to talk about pooping.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

• How we’re identified and how we’re connected to people characterize two of the most important factors for determining the structure of a social network.

• In managed self networks, which correlate to Freud’s Ego, we’re connected to our offline friends, and we are identified as our offline selves. We represent a version of ourselves consistent with the persona we wear offline.

• In ideal self networks, we manifest our Superegos. We’re connected to some of our offline friends, but we’re also discoverable to a network of people who don’t know us. We represent an idealized version of ourselves.

• In true self networks, we’re disconnected from our offline selves and our offline friends. In this Id space, we have the ability to explore new interests and express ourselves in ways that we may not be comfortable with in Ego and Superego spaces.