CHAPTER

THE GUIDING INFLUENCE OF CULTURAL IDEALS

Superego Networks and the Expression of the Ideal Self

I’m going to tell you a story about a friend of mine. You don’t have to believe that this happened, but it did, and it was really, really weird. It was a lightbulb moment for me in understanding the relationship between Instagram and reality. My friend runs a relatively successful leatherworking and denim shop. She makes her clothes by hand because that’s the type of person she is—a maker. She runs her shop mostly online, and Instagram is a natural part of her marketing mix. Her shop’s Instagram profile is polished and well curated. She uses consistent colors, textures, filters, and so on to create a unique ambiance not just within individual posts but throughout the explorable album on her user page.

Her Instagram account represents more than a fabricated, calculated, brainstormed, and strategized brand image. The brand is a part of her natural expression of self. While the account is filled with information about her products, latest concepts, and updates on stock and pricing, she also uses this Instagram profile to talk about her life, marriage, thoughts, and opinions. She takes photos of her blue-dyed hands after long days of working with denim. She posts goofy pictures with her friends. She shares her life in such a way that the people who follow her don’t feel like it’s transactional when she posts about an upcoming sale. It just feels like an extension of her life—this just happens to be who she is. At least, part of her.

Not long after I’d met her, I invited her and her husband to see a band play a show in downtown San Francisco. I didn’t know much about the lineup, and as far as I knew, neither did they. After a small handful of unexciting openers, coupled with growing embarrassment about how they represented my taste in music, the headliner went on stage. This caused a small commotion at our table, and I looked inquisitively at my designer friend who seemed to be the source. She’d recognized the bass player, who had purchased a belt from her online shop, and he was wearing it! She was beyond flattered. We joked about her newfound celebrity and the long list of accomplished musicians who would go on to wear her belts. She recounted a few of the conversations they’d had on Instagram and mentioned what a down-to-earth, nice guy he was.

After the show, I noticed the bassist hanging out by the bar, and I introduced myself to him. I told him about my designer friend who’d made his belt, and I reminded him of the name of her shop. He laughed about the coincidence. He remembered the shop, and when I asked if he’d come back to our table to meet her, he happily obliged. When we were approximately three feet from the table, my designer friend looked up at me, over to the bassist, back at me with a look of pure horror on her face, and bolted. Poof. Gone. I don’t mean that she was in the process of getting up, caught my eye, and just failed to stop her own momentum. I mean she shot away from the table so fast she nearly knocked it over. We agreed that she must have . . . uh . . . gone to the restroom. He headed back to the bar.

When she returned a few minutes later, she didn’t skip a beat, “Why would you do that?!” Stunned, I explained that I figured she’d want to meet the guy in person since she’d designed his belt and they’d chatted on Instagram. She’d want to say hi, right? Wrong. She explained to me that she didn’t really want to talk to him. She didn’t want to meet him in person. She wanted to send him a photo from the show via Instagram to let him know that she loved hearing his band play. She had created a representation of herself, and that representation was too separate from her offline self for the two to merge in an actual conversation. She identified more with—and was more proud of—the representation of self she’d curated on Instagram than the flesh-skin-and-bones she wore around in real life.

Instagram elevates each of us to the level of influencer, even if our audience is small. We don’t have friends on Instagram; we have followers. We share content that isn’t as much about starting conversations or connecting with our friends as it is about emergent self-representation. We curate our feeds a little more than we do on Facebook, we’re a little more selective of the photos we post, and we filter those photos a little bit more. We may be connected to many of the same friends we have on Facebook or Snapchat, but we also have the potential to be discovered by an entire world of people we don’t know. We apply hashtags and tag locations to our content that encourage discovery—after all, we’re only one good post away from the Internet fame we deserve!

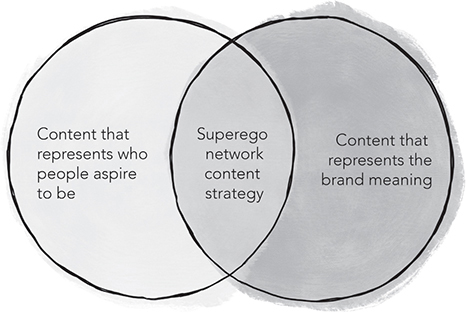

Superego networks are ones in which we’re usually identifiable as our offline selves, have some connection to the people we know offline, and simultaneously have the potential to reach an entire network of people we don’t know yet. Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, VSCO, and even LinkedIn are examples of Superego networks. Each of these platforms employs mechanics like hashtags to connect otherwise disparate users and content (Figure 6.1). In response to these connections of self-expression, we tend to manifest idealized versions of ourselves. Most of us do so naturally and without intent to deceive—it’s not that we’re trying to dupe anyone into thinking that our Instagram profile reflects our whole life. It’s that when we’re invited to express ourselves in space that connects our self-representation with the representations of others, it’s natural for us to curate highlights, positive moments, idealistic beliefs, and pictures that make us feel really, really, ridiculously good-looking.

Figure 6.1 Superego Content Strategy

In the Freudian model, the Superego is the last part of the mind to form, following the development of the Id and the Ego. As you may remember, the Id characterizes the basic, essential drives with which we’re born, and the Ego forms as the desires of the Id face the limitations of the real world—the conscious center of action. The Superego, then, is the combination of our learned rules—the cultural norms that characterize what it means to be a good person, how we ought to relate to the people around us, and who we ought to be. “Don’t hurt other people” and “Don’t take what isn’t yours” are simple examples of early Superego inputs. The Superego continues to grow in complexity, however, as social interactions provide us with feedback. Because the Id deals with unfiltered desires and the Superego imposes cultural rules about what is acceptable, the two are often in conflict with one another, and it’s up to the Ego to mediate between them.

Within the Id, Freud notes that there are a great many drives and impulses that simply aren’t compatible with a large-scale, civilized society. While problematic drives aren’t the only characteristics of the Id, they’re the drives that tend to be repressed and buried deepest in the unconscious, while drives deemed acceptable by the Ego and Superego flow more freely. Inevitably, these repressed drives eventually “sublimate” and find expression in different ways. The process of repression and sublimation is akin to air being trapped underwater. When an idea or drive is deemed unacceptable by the conscious mind, it is “repressed”—that is, it is pushed down beneath the surface into unconsciousness. But like an air bubble trapped underwater, the repressed drive will eventually find a way to surface, even if not via the same path through which it was repressed. That is to say, if a sexual drive is repressed, it may sublimate as something entirely different—something more palatable for the Ego and Superego. For Freud, dreams were windows into the cycle of repression and sublimation and provided important insight for analysis into psychological life.

Freud focused most on aggressiveness and sexuality as the primary forces repressed by culture and its Superegos. In order to deal with these drives that are incompatible with peaceful coexistence, society imposes rules to limit those expressions. Monogamy is a culturally enforced method of limiting sexual expression so that, at least in theory, no one’s sexual expression impedes anyone else’s. And our rules for the expression of physical aggression are even more strict—generally that such behavior is only acceptable in self-defense. Freud contended that when people repressed their sexual or violent drives, those drives might transform through this process of sublimation into more socially useful achievements, like art and academic pursuit.

Repression, however, comes with a cost in Freud’s model: “If civilization imposes such great sacrifices not only on man’s sexuality but on his aggressivity, we can understand better why it is hard for him to be happy in that civilization.”1 In fact, the tyrannical nature of the Superego—and, perhaps, of strict cultural rules—inspired the title of Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents. The book describes in detail not only Freud’s Id, Ego, Superego model but the inherent conflict between the Id and the Superego—the basic desires that emerge from within us and the rules we’ve learned about what constitutes “good” behavior.

On one side of human development is our innate sense to survive, reproduce, and freely express ourselves. On the other are the rules that keep our societies peaceful, functioning, fair, and equal. For most of human development—and for most of the history of life on Earth—the world has been dominated by the former, in which cultural rules have often given way to forcible grabs for power and resources. Freud’s critique in Civilization and Its Discontents could be imagined as the proverbial pendulum having overcorrected from one dominated by Id to one dominated by Superego. Given the cultural Victorianism of nineteenth-century Austria in which Freud lived, that certainly would have been the case.2 In a very different way, we might say that platforms like Instagram and Twitter are once again inflating (some of) our Superegos to tyrannical, unhealthy scales.

IF LEFT UNCHECKED, THE SUPEREGO CAN BECOME A TYRANNICAL DICTATOR

Erring toward the Id devolves the world into chaos, while erring toward the Superego traps us in a tyrannical, totalitarian nightmare. The same metaphor plays out in our online lives. Superego networks can become psychologically tyrannical if we invest too much of ourselves in them. If we allow our fuller offline self to be guided purely by the types of behaviors for which we get positive Superego feedback, we risk putting our happiness and sanity in the hands of people who might not even know us.

We see this imbalance of Superego when people feel a need to film an entire musical performance on Snapchat rather than enjoy the performance themselves. Or when people line up to witness a natural wonder or feat of architecture, only to view the experience exclusively through their phone’s camera. Or when people order a dish at a restaurant purely to photograph it. And especially when the value of our experience is defined by the amount of social media engagement our post about that experience generates. When working properly, the Superego is a force for good, but when we start to lose touch with the anchor of our natural, mostly unconscious self, we start to fracture ourselves in problematic ways. Freud cited this incompatibility of the Id and Superego as the source of many neuroses, or psychological ailments.

Remember the aforementioned research finding that 63 percent of Instagram users reportedly felt miserable after having used the platform? And that Instagram was the platform that showed the most dramatic depressive effects? Those users who reported feeling miserable after using Instagram spent an average of 60 minutes per day browsing the app. The same study noted that 37 percent of responders described feeling happy after using Instagram.3 However, the “happy” camp of people only used Instagram an average of 30 minutes per day.

A 30-minute difference may not seem like a lot, but 30 minutes per day can have dramatic psychological consequences. Research studies about meditation have found that 30 minutes per day of mindfulness can help ward off anxiety, depression, and even more physical ailments like heart disease and chronic pain.4 If 30 minutes per day of meditation can have such profound positive effects, it shouldn’t surprise us that the same amount of time spent browsing social networks could also affect our psyches. The problem isn’t the Superego—or even Superego networks. The problem starts when the Superego goes unchecked and unbalanced. Browsing highlights from our friends’ lives isn’t a problem. Rather, it’s when we become servants to those highlights that we lose touch with our fuller selves.

Instagram started as a photo editing app, and the social network that grew on top of that app reveals its origins. Photography, fashion, modeling, and visual stylings of all kinds thrive naturally on Instagram. These highly visual industries tend toward idealism, often to the point of distortion. These idealistic categories conspire to pull Instagram into Superego space. But there are plenty of photo editing apps and image-centric social networks that haven’t generated the same culture and user mindset as Instagram. We might conclude, then, that Instagram’s culture has as much to do with its structure as with its visual nature.

Different Superego networks also manage to pull ideal representations out of us, but they’re often different idealized versions of ourselves. Instagram’s origin as a photo editor guided the culture toward an idealism of aesthetic, but Twitter culture is very different. While Twitter is very similar in structure to Instagram, its culture is less visual, and it remains squarely in Superego space. Both Instagram and Twitter are organized primarily around user profiles, they rely on one-way “follow” mechanics, and they encourage discovery through hashtags and trending content. Twitter, however, tends to prioritize short-form text as its primary medium while Instagram prioritizes photos and videos. The Superego manifestations of Twitter, therefore, are less based on creating a visual Superego identity and center more around wit, accomplishment, connection, and clout. According to self-admitted Twitter addict and Atlantic writer Laura Turner, “Twitter is a megaphone for achievements and a magnifying glass for insecurities, and when you start comparing your insecurities with another person’s achievements, it’s a recipe for anxiety.”5

In her article “How Twitter Fuels Anxiety,” Turner explains how the platform perpetuates a self-reinforcing cycle of anxiety and self-evaluation. Turner tells us that Twitter provides an endless stream of comparisons against which we can measure ourselves, but at the same time, Twitter culture is generally open to the expression of feelings like anxiety. Brains are tricky though. Turner cites a Harvard study that found that disclosing information about oneself—such as one’s emotional state—activates the same pleasure center of the brain that responds to food, money, and sex. In Freudian terms, it’s a kind of sublimation—we feel anxious, we repress those feelings of anxiety, and then we find a way to express that anxiety in a way that changes our experience into something more consciously palatable. In fact, the same study also noted a relationship between people who spent more time on social media and elevated anxiety levels. Pamela Rutledge, director of the Media Psychology Research Center, draws an evolutionary correlation between the two: “When we’re anxious, we feel compelled to be continually scanning the environment. That’s how we make ourselves feel safe.” The cycle feeds itself.

ENGAGING AUDIENCES IN SUPEREGO SPACE MEANS HELPING THEM MANIFEST ASPECTS OF THEIR IDEAL SELVES

As brands in Superego space, we’re in delicate territory. The content with which people are willing to engage is much more tightly curated. Our audiences’ expressions in Superego space are not only filtered through their selves as known by their offline personal connections but through the representations of their ideal selves. And to complicate the matter, there are many different kinds of ideal self-identities that might manifest in these spaces—some identities are created around looks; some about travel and lifestyle; others about food and exclusive social lives, occupations, political ideologies, philosophies, and other ideals. One person’s ideal self may be the same self another represses, and vice versa. For some brands, this Superego mindset actually helps drive engagement, particularly when the brand represents some part of users’ ideal selves. Remember, when we’re identifiable as our offline selves, the content we engage with becomes our digital clothing. When I engage with a Nike post on Instagram, I’m defining myself as an athlete, just as when I engage with a small, local clothing brand, I’m defining myself as fashionable and offbeat.

In Superego networks, we return to the problem of adding value with a unique set of constraints. How can we provide people with content that speaks to their ideal selves? Or satisfies their need for social approval and acceptance? Or reduces their anxiety as they compare themselves to others? The reason we ought to pose these questions for ourselves is because our audience will judge us much more harshly—“If you don’t add value to my experience, I will not interact with you in any public way.” And “public” is important here because that’s how brands demonstrate their social status in Superego spaces. The principles for adding value remain consistent, although badgeworthy content tends to outweigh bookmarkable content because self-representation is our primary aim in Superego space.

Perhaps the best example of a badgeworthy campaign in Superego space is the Beats By Dre “Straight Outta Somewhere” campaign. Having partnered with Universal Pictures on the launch of the film Straight Outta Compton, the Beats brand drew on a simple but powerful insight—that, like Dre, everyone is proud to represent their hometown.6 The brand created a site called www.StraightOuttaSomewhere.com, which allowed visitors to represent their hometowns within the iconic “Straight Outta Compton” lockup. The tool was simple and very similar to many popular “meme maker” apps online. Users could upload their own background images and replace “Compton” in the logo with their own custom text. Inevitably, people got more creative with the tool than simply following the formula of “Straight Outta [wherever you were born].” One featured an empty egg carton and read “Straight Outta Eggs,” while another used a painting of Jesus in the background with a lockup that read “Straight Outta Jerusalem.”

The campaign successfully walked the razor wire between campaigns that are too customizable, leading to brand safety issues, and campaigns that are too static and rigid to be infusible with anything meaningful by the audience. Campaigns like these take bravery to launch. I can just about guarantee that the Beats By Dre brand manager responsible for approving this campaign was up the night before imagining all of the awful things people could do with their site.

This was the right kind of bravery. Too often, brands shy away from flexible social media strategies that allow their message to be absorbed and co-opted by their audiences for fear of bad actors. When someone used the Straight Outta Somewhere site to create something lewd or offensive—which they absolutely did—the final content was more reflective of the person posting than it was of the Beats By Dre brand. The Internet allows for a scary amount of sharing and editing, but that doesn’t mean we just keep our brand under glass.

The Straight Outta Somewhere campaign afforded its engaged audience a truly unique mode of self-expression. How often do we get to talk about our hometowns? And how many of us have parts of our identity rooted in the places from which we come? It’s also worth noting that the output of engaging with the campaign was itself badgeworthy—the content created by the www.StraightOuttaSomewhere.com generator was cool and worthy of posting. It’s easy to imagine a similar brand insight resulting in a hashtag-based photo campaign that prompted people to “Share a photo of your hometown!” Had Beats gone that route, this campaign would have been dead before it started. These low-effort stabs at driving user-generated content are all too common in social strategies and lack a basic understanding of why people engage with brands in the first place.

At least part of the success of Straight Outta Somewhere is in its meme machine—the flexible Straight Outta Somewhere lockup was consistent enough to be recognizable while flexible enough to become different and interesting for each iteration. If the brand had executed our hypothetical alternate strategy and asked people to share photos of their hometown, we’d be asking them to create a new meme machine with every submission. What copy should I include? Should the photo be personal or reflective of the town? Should I say something about myself or the place? Straight Outta Somewhere simplified the process of self-expression by providing the meme machine shell in which many different memes could live.

“Where are you from?” is the type of question that we’re generally very comfortable asking as normal humans but that is terrifying for many brands. What if someone is from a poor area? What if the person had a tough childhood and used this branded prompt as a place to vent? What kinds of things might we be attaching to our brand image by asking such a question? But part of the success of the Straight Outta Somewhere campaign is exactly that—the question had weight to it. It gave people a real avenue to tell stories about themselves, or at least to represent parts of themselves they don’t often get to represent. Where are you from? How do you represent that? And how do you represent that? These are questions with actual connections to culture. They’re questions that, when answered, tell us something important about a person.

Too often, brands pay lip service to the idea of wanting to “become culturally relevant” without being willing to engage a topic with cultural weight. We need to allow conversations to flow into space where people actually care to engage. When we do, the results speak for themselves. The Straight Outta Somewhere campaign became the first number 1 trend across Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook simultaneously. The site drove more than 11 million visits, 8 million downloads, and 700,000 shares in social.

Self-expression in Superego networks isn’t always heavy or serious. Humor plays a major role, and not always in straightforward ways. Often in Superego networks, we make light of what bothers us most or tease ourselves about our insecurities. It’s a way of bolstering our ideal selves. As full, complex humans, we might be insecure about our weight, appearance, how a tweet went over, getting drunk at a Christmas party, and so on. But in Superego space, we may well hide these fears in plain sight by making self-deprecating jokes and pretending we’re impervious. One way self-deprecation manifests in social media is through over-the-top fast-food fandoms. Part of the reason brands like Taco Bell, Wendy’s, and McDonald’s drive massive amounts of engagement in social media is what they represent—light-heartedness, pleasure in the moment, contrarianism to health culture, etc.

The Heinz brand leaned into this tendency for people to rally around their favorite foods in a controversial campaign about a new product called “mayochup.”7 Mayochup, a combination of Heinz mayonnaise and ketchup, wasn’t actually a product the brand was trying to sell. The campaign was designed to drive awareness of the new Heinz mayonnaise. Sounds ludicrous, right? To announce an actual product, they created a fake product and produced a campaign around it . . . ? Strange as it may sound, the campaign far overdelivered on its goals—Heinz generated over a billion impressions in 48 hours and saw a 28 percent lift in awareness for their mayonnaise product. The brand could easily have taken the straightforward path to launching a product—just post a product shot with a white background sweep across owned social channels and wait for the dozens of engagements to roll in. By creating a fake, divisive product, the brand stirred up a tongue-in-cheek debate that drove massive amounts of engagement and earned reach.

At launch, Heinz shared a mocked up photo of mayochup and posted it on Twitter—“Want #mayochup in stores? 500,000 votes for ‘yes’ and we’ll release it to you saucy Americans.” The tweet generated more than 25,000 likes, 14,000 retweets, and nearly a million votes. The “yes” crowd won by a narrow margin—55 percent and just enough to get the product on shelves. In true Twitter fashion, the debate between mayochup proponents and naysayers raged for months afterward, often leveraging the #mayochup hashtag. Heinz was able to harness the often disagreeable but ultimately good-humored nature of Twitter culture by putting forth a debate too absurd to take seriously. Is it fry sauce? Is it fancy sauce? Is it Russian dressing? Is it disgusting? Twitter couldn’t decide, and that’s exactly what you need if you’re a brand launching a new kind of mayonnaise.

In a followup phase to the #mayochup campaign, Heinz took to Twitter once again to determine which city should receive the first shipments of product.8 The brand encouraged people to tweet using #Mayochup[YourCity], which was a brilliant mechanism to create local relevance in a large-scale campaign. By pitting different cities against one another, the brand was able to respark the debate, and people filled their cities’ hashtags with gifs representing their excitement, memes in anticipation, and even videos of people chanting their cities’ mayochup hashtags. Like the Beats By Dre campaign, the Heinz brand provided a platform to infuse the campaign with their own self-expression.

When executing a campaign across a large geography, many brands default to localization strategies—adapting content and targeting it only to particularly relevant regions. When the goal is to spark discussion and engagement, we need to rethink that instinct. Heinz may well have targeted people in Chicago with creative touting #MayochupChicago, but the structure of the campaign allowed these local conversations to intertwine and affect the broader mayochup debate. What happened in #MayochupChicago meant something to people in #MayochupDetroit, and vice versa. Allowing these local conversations to meet each other helped spark new organic conversations and kept the debate alive.

Both the Straight Outta Somewhere and Mayochup campaigns played on how people define themselves in social media to gain relevance. Both campaigns acted as platforms for the self-representation and expression of engaged users. By definition, Superego networks tend toward badgeworthy content because self-representation is a fundamental part of the value we derive from participating in them. But bookmarkable content also thrives, especially within categories that are inherently badgeworthy.

Bookmarkable content simply needs to pass through the ideal self test: “Would I be glad that people know I saved this?” Food and recipe content is a good example of the principle. Food photography is an organically popular, badgeworthy stream of content that’s well represented in Superego networks. But bookmarkable recipe and kitchen hack content also thrives in Superego space. This content isn’t only about showing a badge. It helps viewers understand how to break down complex recipes, learn to do something new, or dress up something ordinary. Many of us aspire to be great home chefs and would love to demonstrate to the outside world how crafty and creative we are in the kitchen.

The content that demonstrates the steps in a new recipe, then, isn’t just about helping us learn. It’s also about representing the depth of our interest. We aren’t just consuming the final products, we’re learning how to create them. The @buzzfeedtasty account boasts more than 34 million followers on Instagram and exclusively features recipe hacks and how-tos.9 It’s not uncommon for their short-form videos to generate a few million views each. Fitness, niche hobbies, photography, and really any informational content that helps people understand an interest they’re proud to share with the world has strong potential to succeed in driving Superego engagement.

CONTENT CAN BE BOTH USEFUL AND EVOCATIVE OF PEOPLE’S SUPEREGOS

The Lowe’s brand developed a particularly strong series of bookmarkable content that spread naturally around Superego space with its #LowesFixInSix campaign.10 Executed on Twitter and Vine (aw, remember Vine?), the concept was simple, and the execution was polished but relatable. The Lowe’s creative team at BBDO developed a series of six-second videos that demonstrated simple life hacks, DIY projects, and home improvement tips. The creative team cited the low-cost production as a major driver of success because it allowed them to create over 100 pieces of content over the course of the campaign. When it comes to developing content with strong organic success, it’s almost impossible to predetermine a winner, especially from the concepting phase, so investing in a higher volume of creative output is generally a good strategy. Production value usually has very little to do with what drives organic sharing.

The campaign creative was executed brilliantly and leveraged low-barrier, easily shareable meme machines to deliver ideas. The Vine platform proved particularly beneficial in constraining the brand’s meme machines to be light and efficient in their communication. Not only was Vine a trending platform at the time, but its format was also conducive to social sharing generally. The platform required every post to be a six-second, looping video—essentially, a short gif with sound. These short-form gifs were well optimized for every social channel because they required such efficiency of communication. Videos featured life hacks like using rubber bands to remove stripped screws, using a rubber mallet and cookie cutters to make the perfect jack-o-lantern, and using painter’s tape to hang level shelves.11, 12, 13

The #LowesFixInSix content was both useful and representative. Hopefully, the usefulness of the videos is obvious—that was their primary purpose. But the videos were also representative in that engaging this content communicated something about the sharer. Sharing these videos might say something like, “I’m new to home maintenance, and these are the kinds of problems I face now,” or, “I’m a proud homeowner, and here’s a video of something even I stood to learn,” or, “I’m a very handy person, so I already knew how to do this, but it’s been so helpful to me that I think you should know it too.”

By creating content that is both informative for its audience and lends itself to self-expression, the Lowe’s creative managed to spread naturally throughout social media platforms and earn significant reach. The #LowesFixInSix videos generated millions of views on Vine alone—and no, Vine didn’t have an advertising platform to help pay for reach. Its video showing how to use a rubber band to remove a stripped screw alone drove 7.4 million plays. Because Lowe’s was an early adopter, it was able to carve a new niche within the Vine platform, and because the Vine platform itself was still up and coming, the brand was able to ride a wave of organic popularity. Much of the copy in the videos would be considered out of place by today’s standards—“Lighten up! DEWALT 2-PC 20V Combo Kit was $199, will be $149 on Black Friday.”14 Many posts had similar down-funnel, sales-centric copy. But because the content added value, the sales messaging wasn’t a problem. That’s another big mistake many brands make throughout their social media strategies—we’re advertising things to sell. We know. They know. We know they know. And besides, they know we know they know. We don’t need to hide it. We just need to add value while we’re doing it.

Would the #LowesFixInSix creative work in Ego space? Absolutely. The brand shared some of these videos on Facebook where many of them generated hundreds of thousands of views.15 As frequently happens with organic content, it’s not unusual for stellar social media creative to find audiences across platforms. Given that both are generally spaces for self-representation, many of the best practices that work on Facebook also work on Instagram, but they succeed for different reasons.

One of the main differentiators between Ego and Superego spaces is that in Superego space, we’re less bound to our offline sense of reality and identity. While our ideal self is a factor when participating in Ego space, it’s embodied in Superego space. We often express ourselves vicariously through people who represent aspects of our ideal selves. If we identify with a particular kind of fashion, we might follow and engage a celebrity designer. If we identify with a particular sports team, we might follow the franchise or our favorite players. If we identify with adrenaline rushes and extreme sports, we might follow GoPro.

GoPro shares the epitome of aspirational content: professional extreme athletes performing ludicrous stunts. Most of us, and I apologize if I’m projecting here, probably don’t ride our bikes down jagged mountain outcrops, skydive in formation, surf waves as tall as buildings, or scuba dive in underwater caves. But that doesn’t mean we don’t identify with what those represent—daring, adrenaline, conquering death, nerves of steel. It also doesn’t mean we don’t want a camera that could capture all of those extreme activities. Subscribing to GoPro and engaging with its content is a way of communicating that we’re adventurous, that we’re energetic about life, and that we’re willing to confront our fears. With more than 16 million followers on Instagram and over 2.2 million followers on Twitter, GoPro is a brand that has embraced the natural Superego niche cut out for it.16, 17

The same phenomenon is true of the fitness category in general. The most-followed fitness influencers on Instagram aren’t those with the most practical knowledge or the people who went from being reasonably out of shape to being reasonably in shape. They’re the most ludicrously fit (or at least ludicrously fit-looking) people on the planet. Stars like fitness model Michelle Lewin with over 13 million followers, professional bodybuilders like Kai Greene with over 5 million followers, and celebrity trainers with abs-popping-out-of-their-abs like Simeon Panda with over 5 million followers win the eyeball contest.18, 19, 20 Is that because people like to follow their training routines? Or is it that they offer the best inspiration for our fitness goals? Not even close.

We enjoy seeing and engaging people who’ve reached beyond their limits—or maybe our limits—because these are the people who express our visions of our ideal selves. Nike’s advertising has anchored itself squarely on this very insight—we’re all athletes. When we wear Nike shoes, when we’re at the gym ready to quit, when we’re debating whether or not to get out of bed for a workout, a part of us imagines ourselves as the superathletes we see Nike represent, and we feel empowered. The brand places us in that same class of athletes.

Elevating a brand to the level of Superego aspiration is no easy feat, but for some categories, the fit is reasonably natural. Fashion, food, fitness, music, and any category that represents an aspirational hobby or interest is usually able to find a way to align with people’s ideal selves. One way brands have evolved to leverage this tendency for people in Superego space to admire their idols is to hire those idols as influencers.

Superego networks go hand-in-hand with influencers in part because they tend to relate to some aspect of our ideal selves. Superego network structures also allow influencers to find and grow their followers relatively naturally. When influencer campaigns are done right, brands are able to borrow the credibility influencers have built, offer something useful to those influencers’ audiences, and convert a swath of new customers. Unfortunately, it’s easy to take an influencer campaign down the wrong path—overpriced, ineffective creative lacking any viable reach, or worse yet, embarrassing ourselves in front of the audience we want to convert.

INFLUENCER CAMPAIGNS REQUIRE THAT WE PUT OUR BRAND MEANING IN THE HANDS OF OUR PARTNERS

Influencer integrations are more art than science. Too much brand touch, and the partnership feels forced and inauthentic. Too little, and the partnership will fail to propagate the advertising message and generally confuse the influencer’s audience. The Madewell brand is a best-in-class example of how to run influencer campaigns. The brand is well known for its ongoing influencer marketing, and that makes particular sense for them as a relatively young fashion brand.21 Instagram has created an entire class of amateur-bordering-on-professional models, and Madewell curates a range of aspirational-but-relatable influencers who fit the style of their clothing. The brand successfully balances partnerships so that they feel like natural parts of the influencers’ lives and are clearly tied back to the Madewell brand and products.

Madewell doesn’t fall into the trap of the forced “key message,” which is a cardinal sin of influencer marketing. When a brand provides copy or requests that influencers use a particular key phrase in their caption, the content almost always feels inauthentic and contrived. Probably because it is. “But we’re paying them to post it!” says your client. And yes, that’s a totally fair point. We just need to be a little more creative with how we integrate our brand’s message. Influencers can spend near full-time working hours creating, maintaining, and growing their channels—their audiences know them very, very well. Even if our brandspeak caption passes our own sniff test, it probably won’t pass the audience’s.

Madewell utilizes a particularly brilliant tactic to bridge the gap between key messaging and the influencers’ natural editorial voice. The brand often provides influencers a prompt rather than suggested copy. In a campaign around Valentine’s Day, Instagram user @citysage created a post for Madewell denim.22 In her photo, she’s sitting with a red coffee mug in Madewell jeans with her legs kicked up on some Instagrammy pink chairs. She tells her fans, “In honor of Valentine’s Day @madewell1937 asked me to share some things I love . . . like the first cup of morning coffee, the comfiest goes-with-everything jeans, the cheeky romance of pink + red . . . happy ![]() everyone! #denimmadewell #flashtagram (Photo: @teamwoodnote).”

everyone! #denimmadewell #flashtagram (Photo: @teamwoodnote).”

The post managed to hide the ickiness of an influencer integration right in plain sight—“Madewell asked me to do this.” Madewell often employs multiple influencers for any given campaign, and the prompt also helps to address this problem of scalability in a strategic way. A prompt allows each individual influencer to interpret things slightly differently. Even if we were able to sneak a brand phrase naturally into an influencer’s post, if the phrase is repeated across multiple influencers, it’s easy to recognize exactly from where the inauthenticity comes. (Hint: it’s us.) Had Madewell asked influencers to post the line, “I love my @madewell1937 jeans because they’re comfy and go with everything!”, the campaign would have fallen into that uncanny valley of social copy and felt completely contrived. But the broader prompt of “Share some things you love” is adaptable and scalable enough to generate a wide diversity of on-brand content from influencer partners.

Madewell also leverages consistent hashtags when working with influencers, not just for particular campaigns but throughout their social activity. Not only does this help tie a long history of branded influencer content together but it also encourages user-generated submissions and organic sharing. When influencers share updates with their Madewell hashtags, a particular aesthetic is created in the accumulation of those posts. And because in Superego space we’re all mini-influencers, it’s natural for us as followers of those influencers or lovers of the Madewell brand to also share our photos with the same hashtags. Rather than creating a new line of jeans and writing cringe-inducing copy that asks people to, “Share photos of why you love Madewell denim!”, the brand has created an engine of user-generated submissions by remaining understated in its calls to action and allowing the social network’s mechanics to work naturally. In fact, the brand has a dedicated “Community” section on its website, which features photos from their various hashtags, recognizing their fans for contributing.23 Madewell uses Instagram to empower fans to post their outfit of the day right alongside their influencer idols’, making particularly strategic use of Superego space.

In Superego networks, our social standing means everything, especially as brands. High follower counts, strong engagement with our photos, tags and retweets from influential accounts are all ways we build credibility in Superego space. As brands, we tend to default to an apologetic demeanor in social media. At the slightest sign of resistance, we’re quick to back down, remove the post, delete the video, scrap the campaign, fall to our knees, and beg the social media gods for forgiveness. As brands in Superego space, we need to build up a thicker skin than may seem immediately comfortable. Among a handful of other things they get absolutely right, the Wendy’s brand is a prime example of taking criticism in stride and staying on course toward a strategic, thoughtful, and entertaining outcome.

Perhaps more than any other brand, Wendy’s has managed to become part of meme culture. And not in a killed-by-the-locals-and-cooked-in-the-communal-stew kind of way, either. The brand has genuinely been accepted by the tribe. Meme culture and Superego networks have an interesting relationship, and in some counterintuitive ways, much of the humor that thrives within Id networks also succeeds at propagating in Superego networks. Sometimes that’s because self-deprecating humor is an aspect of many people’s Superegos, sometimes it’s because being in the know about cutting-edge meme culture is an ideal for some people, and sometimes it’s because Superego networks tend to have a significant representation of anonymous profiles. Regardless, Wendy’s succeeds in driving massive amounts of engagement by understanding and contributing to meme culture.

One of the easiest places for brands to fail in meme culture is incorrectly using a meme machine. Whether it’s messing with the cadence of the text, using the wrong font, or misusing the sentiment of the original meme altogether, getting the meme machine right requires patience and attention to detail. When Wendy’s demonstrates that it has mastered a meme by successfully adapting a new format, the people who engage with the branded meme are expressing two things. First, Wendy’s has made an entertaining meme that’s relevant to meme culture. And second, I’m in on the joke too. Because meme culture uses ideas and meme machines to define boundaries, and because those memes are constantly evolving, people identified with meme culture have an incentive to continue to demonstrate their membership in the tribe. Wendy’s has learned to speak the language fluently.

Meme culture truly does represent a new language, and learning to speak a new language isn’t easy. When we’re learning something new, we’re bound to make missteps. Inevitably, as Wendy’s has honed its brand voice and meme culture-related content, the brand has made mistakes. And undoubtedly, the Wendy’s team has received messages along the lines of, “Get out of meme culture—you don’t belong here.” There are plenty of social media teams who hear that feedback a couple times and scrap the strategy. But not Wendy’s. Wendy’s doesn’t back down when its content is critiqued, and that’s absolutely vital to maintaining a respectable demeanor in Superego space. That’s not to say that Wendy’s doesn’t take care of customers who’ve had bad orders. When something goes wrong, the brand responds with a sincere message along the lines of, “This isn’t the service we expect. Please DM us with the location and your contact info so we can look into this further.” But Wendy’s is known for its Twitter roasts.

When one user provoked the Wendy’s account with, “If you reply I will buy the whole Wendy’s menu right now,” the brand responded, “Prove it.”24 The original poster retorted with a photo of a trash bag and the caption, “Here’s your proof ![]() .” Wendy’s clapped back with, “Thanks for sharing your baby pictures.” That response alone generated over 3,000 retweets and over 15,000 likes. While the tactic is hilarious and engaging in its execution, the mindset is actually deeply important in Superego space. It says, “We’re confident in our brand. We won’t be bullied.” And let there be no doubt—brands get bullied on Twitter all the time.

.” Wendy’s clapped back with, “Thanks for sharing your baby pictures.” That response alone generated over 3,000 retweets and over 15,000 likes. While the tactic is hilarious and engaging in its execution, the mindset is actually deeply important in Superego space. It says, “We’re confident in our brand. We won’t be bullied.” And let there be no doubt—brands get bullied on Twitter all the time.

Unfortunately, most brands are so apologetic in social media that they seem guilty just for occupying space. Some people respond negatively to the memes Wendy’s posts, but it takes that feedback in stride, and when appropriate, isn’t afraid to jab back. As brands, we need to understand the difference between genuine, widespread backlash and a handful of negative comments. To demand respect within the culture, we need to stand steadfastly behind what we say, and we need to exhibit brand behaviors that align with what we say our brand is.

When we’re organized around profiles that facilitate self-representation, we are connected to our offline identities and to many of our offline friends, and we have the potential to reach a world of people we don’t yet know, it’s natural for us to manifest an ideal version of ourselves. We’re not dishonest in Superego space. We just tend to embody a more curated persona than we do in networks based on mutual connection and anonymous exploration. As brands looking to engage audiences in Superego space, we need to find ways to align with people’s ideal selves—or find a way to allow our brand to represent something related to our audience’s ideal selves.

Superego space puts us in a mode of emergent self-representation. The photos we share, the content we engage, and the friends with whom we interact are the ways we define ourselves to the broader network. As brands, we must not only find ways to add value for our audiences’ ideal selves, we must also maintain our authenticity and consistency. Finding ways to add value in Superego space requires a strategic understanding not only of who the audience is but who they aspire to be. If we can find a way to help our audience express their aspirational selves, engagement will follow naturally.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

• Superego networks are ones in which we’re usually identifiable as our offline selves, have some connection to the people we know offline, and simultaneously have the potential to reach an entire network of people we don’t know yet. We’re representing idealized versions of ourselves.

• To drive engagement in Superego networks, we have to create content that aligns with some aspect of people’s ideal selves. That requires an honest, self-aware understanding of what our brand represents.

• Nearly every piece of content with which a person engages in Superego space is in some way badgeworthy.

• Social status is extremely important in Superego networks, and we can demonstrate our status through high levels of engagement, growing our following, and partnering with other reputable influencers and brands.

• Influencer integrations can be strong tactics for building relevance and lifting social status, but they must feel organic in order to meaningfully sway opinions.