The Vision—Strategy and Planning Are Not the Same Thing

Strategy Isn’t Planning

Strategic planning is an oxymoron, says Alan Weiss, PhD. In his book Best Laid Plans,1 he tells us:

The failure of strategies is most often—yes, most often—not the result of poorly conceived strategies but rather the result of poor implementation. Or to be more precise, it is the result of a weak connection between the strategic vision—the “what” the organization is trying to become—and the implementation—the “how” of the organization’s approach to attain the vision.

I will go further and suggest that in most small- to mid-sized businesses, there isn’t a “what” the organization is trying to become, just a lot of loosely aligned “how’s” being implemented, often with vigor. Companies need to communicate what they are trying to become. The blame for this, as Dr. Weiss says, is that the oxymoron “strategic planning” muddies waters that are already opaque for many leaders. Strategy is top down and gives people their goals, but planning is bottom up and strangles senior management.

The F in FIT is all about focus, which is establishing what your organization is trying to become and how you plan to approach that vision. The first step in unleashing your people’s hidden business development powers is communicating what your company is trying to become. This goes beyond getting their heads to nod in agreement because what we need is for them to take the next step and communicate what your company is becoming to prospects, customers, and vendors. For that to happen, you must start with where you want to go.

Peter Fink is the owner of Certified Transmission headquartered in Omaha, NE. They own and operate 13 retail locations in four states and are one of the largest suppliers of remanufactured transmissions in the world. It’s an impressive operation that started with a two-bay gas station, Peter’s tool box, and one-thousand dollars. The first time I met Peter, I asked him what his vision for the company is.

“To dominate our market,” he said.

Fair enough, I thought. “And how will you know if you’re dominating your market?” I said, “Is there some metric or measurement you’re using?”

He looked at me like I didn’t hear him the first time. “I want all of the business. All of it.”

Now I looked confused because I couldn’t tell if he was pulling my leg.

“And as long as I see other transmission places,” he continued, “I know we’re not there.”

I’ve replayed that conversation in my mind over the years because at first, I thought he was just giving me a rah-rah, we must win, coach pitch. I’ve concluded that he wasn’t. What he was giving me was the same message he gives to each and every one of his people. Their vision is to be the only place you would ever need to go for your vehicle’s transmission problems. They want to dominate the market by being the best-informed, most courteous, trustworthy, and dependable repair shop in each city they operate in. They want the remanufactured transmissions they sell to hundreds of other retailers to reflect that same attention to quality. If I sound like I’m gushing, it’s because I have learned that the simplicity of his message, his vision of being the only place anyone would ever need to go to for transmission problems, is the best example of a crystal clear strategic vision that I’ve experienced.

That’s what the Focus in FIT requires you to do. To be as clear in your vision as Peter Fink is in his. To get there, we have a set of exercises that will help your leadership team. Before we explore those exercises, a quick word on leadership teams.

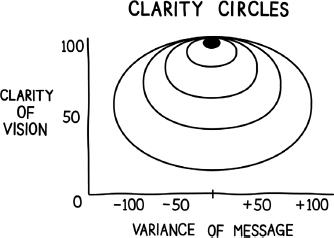

The leadership team setting the strategic vision is small. In most cases, smaller than your current leadership team. For most mid-sized companies with fewer than 150 employees, we recommend three. The reason for this is because to get a clearly communicated vision, there can be no message variance on the leadership team. Once we get beyond the leadership team and into the rest of your organization, the vision starts getting watered down. The further you are from the leadership team, the more watered down it becomes. To combat this entropy, we begin with a small group that shares the same strategic vision and can clearly communicate it to the next group, which is the planning committee. Refer to Figure 3.1, clarity circles.

At the top of the y-axis, at full clarity, and the middle of the x-axis, with no variance of message, is the leadership team. Even with a small team of three, getting full commitment to one vision of the future organization is hard work. Contrast that with what my local chamber of commerce did. They invited 200 stakeholders to participate in their strategic planning activities. A nonprofit that I volunteer for invited 13 board members to a half-day retreat to set a strategic vision. From the outside, both groups have a strong mission, vision, values statement. On the inside, multiple agendas are pursued, and effectiveness is diminished.

If it helps, imagine a fire hose. I used to work in an oil refinery on the safety crew. One of the perks of the job was dressing up like a fireman and discharging water through the hoses to make sure everything was in working order in case of emergency. The fire hose nozzles were shaped like guns, but instead of a trigger by your finger, one hand holds the pistol grip, and the other hand works another handle on top of the nozzle that controls the flow of water. Once your flow is set, you turn the front of the nozzle to set the spray pattern. The pattern ranges from wide enough to drench the full façade of a two-story house with a heavy rain, to a narrow pattern powerful enough to punch through a brick wall. The smaller your leadership team is, the narrower your stream will be, and the more powerful your message will be.

Figure 3.1 Clear Vision, Clear Message

Clients have pushed back on this idea, pointing out that studies show that the more control over an outcome their people have, the more likely they are to buy into the vision. That’s not exactly right. As we stated in Chapter 2, your people will buy into the vision for any number of reasons that are not directly related to the vision. What they need control over, what they need buy-in to, is how they get there. That is where the use of self-identified strengths, and autonomy come into play.

The size of your leadership team needs to be no more than three. The size of your planning committee I leave up to you. That’s where I’ll let your leadership team demonstrate their clear message, and do it in crystal clear terms, as they ask for input on how to get there.

Field Notes

Jim Anderson’s career in finance has led him from running multinationals, to running a malting company (yay beer!), to his current career in private equity. As we talked about the premise behind The Human Being’s Guide to Business Growth, he shared his Butterball Turkey story.

Early in his career, Jim’s company purchased Butterball Turkey and he was on the team responsible for integrating them. When he arrived, he found a business easy to describe—they grow, kill, and package turkeys—but a leadership team that struggled to identify who the customer was. There were distributers, food companies, grocers, and co-ops creating a complex definition of their “customer,” and it resulted in an organization heavy in consultants and key performance indicators (KPIs).

“I saw the need for simplicity because the business is simple at a high level,” Jim said, “they sell turkey.”

Similar to FIT, Jim started with a clear vision of the future which started with their definition of a customer. “The customer,” he said, “is the consumer of turkeys. Our job, therefore, is to make consuming turkeys a great experience.”

If you devour business stories like I do, the Butterball Turkey hotline immediately comes to mind. It’s an innovation that comes directly from that focus. It bypasses all of Butterball’s business definitions of “customers” and connects staff directly to the consumer, focused on making turkey consumption a great experience.

Jim knew business is complex, so he saw his job as simplifying the company’s focus and reminding his people to keep the consumer in mind each and every day. Jim’s Butterball story speaks to the power of Focus.

Strategy in Hours

It’s time for your first strategic vision exercise. The days of 5-year and 10-year plans are gone. Time and distance, regardless of your industry, is compressing and each step you take into the future changes that future. To work in this new reality, you need a process for setting a strategic vision that doesn’t take a retreat, multiple days offsite, or thick binders of materials to be produced. You need a process that lets your leadership team—your small, agile leadership team—quickly set a strategic vision that your planning committee can work with. Let me show you how we do it.

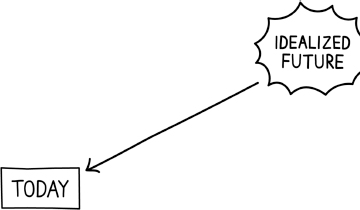

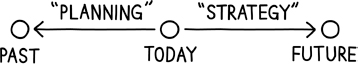

Step one: Start your strategy sessions by framing this concept in Figure 3.2, past/future:

Your strategic vision is firmly entrenched in the future and is divorced from the past. What I mean is the future is where we want to go without the constraints of today. It’s aspirational. The reason for that is because aspirational visions are emotional and it is emotions that drive action. It’s emotions that shake the trees and move the mountains. Logic won’t do that. Logic is what we use to justify decisions, but emotion is what drives action.

Figure 3.2 Strategy looks to the future, planning looks to the past

Think about your last beach vacation. The idea of sunshine, umbrella drinks, and having nothing to do for a week is an emotional idea. The idea of sunburns, overpriced buffets, and being stuck in an 11 p.m. layover at Chicago O’Hare on the way back is an emotional idea. One drives action to go, the other may drive action to skip the trip. Either way, once that decision is made, logic kicks in. If you go, logic says you got a great deal, you’re recharged and getting more done, and your team became more independent without you there. If you stay and catch up with work instead, logic says that you saved a bundle and you were there for the team when that emergency happened, because, let’s face it, there is always an emergency.

Strategic vision is three parts emotion to one part logic. Planning, on the other hand, is three parts logic with a splash of emotion. To get the recipe for your strategic vision right, ignore your present constraints in your strategy meeting today, because you are going to focus on the future.

Step two: Make the future your own

The future will look a lot more like today than we think. The exercise for step two is to make the future your own by putting your small team into the right state of mind. To do that we are going to use an exercise that the futurists like to call, remembering the future. To get there, we need three pieces: A place, a client, and an event.

Get to the flip chart, put your names across the top, and down the side, list place, client, and event. To start, go around the room and pick a place that you know well. It can be a vacation spot, your kid’s college town, or your hometown. The only requirement is that you know it well. List each attendee’s place under their name.

The client line is a company that you know well enough to name your key contacts, their main business drivers, and a little about their customers. Like “place,” the requirement is that you know the client well.

The last element of the exercise is to figure out why each of you are with your clients in that place at the same time. What is the event bringing you together? Everyone needs to take seven minutes to come up with their story. For instance, if I come up with Manzanillo, Mexico as a favorite place, and my pharmaceutical consultancy as a client I know well, why would we both be in Manzanillo at the same time? Let me take a minute and make something up.

One of the only reasons I can think of us being down there is to entertain a large client with a deep-sea fishing excursion and client planning session. It’s not out of the realm of possibility, and I can almost feel the sun on my face as the boat jumps the waves out to our spot. Past the big rocks protecting the bay and out in the open waters where the trophy fish are waiting.

Did it ever happen? No. But since I know Dan well, and I know the spot well, it’s easy to imagine a reason for being there and it almost feels like it’s happened. As a matter of fact, I imagine the movie The Fugitive with Harrison Ford. Dan and I are entertaining Devlin McGregor, the giant pharma company, and getting our picture taken with a monster fish.

That’s how we center the leadership team to imagine the future. Next is the meat of the exercise, imagining our industry three to five years out. What are the changes shaping our industry? What are the new challenges our customers will be facing? What will the regulatory environment be like? What technology is going to re-arrange how we operate?

That leads to answering the smaller questions our people will ask.

• What is our company’s purpose in that future?

• In that future, we’ll know we’re successful when what happens?

• What do our company values force us to act like in this future?

What you end up with is a future that your leadership team can fit answers into. Most leadership teams light up at this because it feels like progress, and it is. This is how we see the future and this is how we’ll fit in. This is where our company will provide value in the future.

Step three: Gauge the distance between where you are today, and the future you just described.

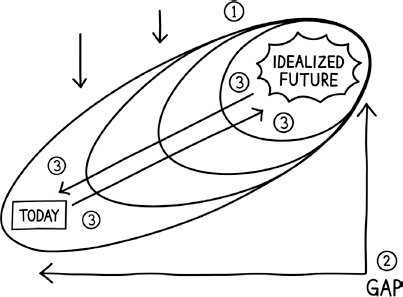

Figure 3.3 Work from the future to today

On the white board, Figure 3.3, future to today, helps describe the process thus far.

It’s here where the joy from step two dissipates. This is the right time in the strategy day to look at the limits of today’s organization. Do we have the right people? Do we have the right capital structure? Do we have the right technology?

We suggest not lingering here except to put in place some of the metrics that you’ll be using to steer the company into that future. This is where we talk about the market size, the number of customers, the cost of operations, the number of employees, and whatever other metrics will govern the business. We don’t keep an exhaustive list because our clients have very little problem coming up with items to track. This is where you are the content expert and you make a list of possible metrics you can give to your planning committee.

Step four: Set your markers from the future to today

With a vision of the future and a list of metrics, you’re ready to jump back into the future. We start with the date we were using in step two and for this example, let’s say it’s five years into the future. Our next exercise is going to take us back into that future and we’ll start by asking this question:

What do we need in place by year four, to make year five a reality?

The question is important because the gap you’ve identified between today and the future is, and needs to be, way too large for you to get to right now. A lot of things need happen, most of them good, for your place in the future to be secured. Instead of jumping right into that future, we’re going to go almost into the future. We’re going to its doorstep and asking ourselves what the doorstep looks like.

How many customers will we need the year before we realize our vision?

What will the product mix look like in the year before our vision happens?

Who will be on our team, trained and ready to lead our people into that vision?

This process is going to be repeated, as we see in the circles that come from the future back to today in Figure 3.4.

Figure 3.4 Identifying the distance from the future to today

We’re going to get our small team on the same page knowing what has to happen right before year five? And what must happen right before year four? And before year three?

Before we know it, we’re into asking ourselves what needs to happen in the coming year, and that is when the strategy meeting ends, because what is going to happen next is planning, and that requires the buy-in from your next group. You should have a rough outline that looks like this in Figure 3.5.

This process takes less than a day to implement and only requires quarterly maintenance to be effective. Each quarter, the leadership team gathers to answer this question: What, if anything, have we learned in the last quarter that will change our vision of the future and how we fit in?

Figure 3.5 Creating a plan to bridge the gap from today to the future

If we’ve done our job, your leadership team should describe the exact same future to anyone who asks. It’s my test. I should be able to stop you in the hall, at any moment, and no matter who I ask, the description of the future will be the same.

Aligning Decision Making and Strategy

Armed with our clear vision of the future, we’re ready to let our people make plans for how to make the strategic vision a reality. This is where traditional planning takes place. We’re going to ask the planning team to look at the destination and plot a course for how to get there. Specifically, we want them to come up with the metrics that will show us that we’re either on the right track (green), concerned that we’re off track (yellow), or not going the right way (red).

I’ve seen this approach used to great success because it’s a management tool that everyone understands. If you’re on the right track results should be in line with expectations, if you’re concerned, the management team should be helping with ideas on how to fix the direction, and if a manager knows something isn’t working, everyone needs to help troubleshoot the problems. I’ve seen this approach fail too. It requires honesty and vulnerability, which we don’t have space to address here, but for managers to seek help, they need to trust the people they open themselves to.

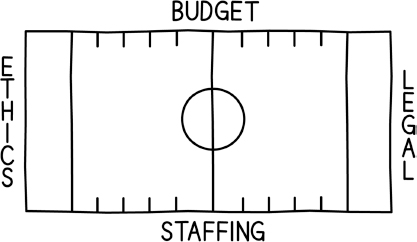

This stage of the FIT process is where we introduce using self-identified strengths in decision making aligned with strategy. That’s a mouthful but it’s where our leadership will begin to take ownership of the vision and begin to communicate it to their employees, vendors, and customers. This is where we lay out the playing field that our people can work on.

The playing field is the best analogy to help your planning team align their decision making with strategy because it requires empowerment. If I know where the out of bounds is, I can move faster and more accurately with my decisions. We suggest putting a field on the white board and using the borders as discussion points for the constraints that your organization will use for decision making. It looks like Figure 3.6, the playing field.

For your discussion, we suggest you use boundaries that are important to you, but in a pinch, there are some go-to boundaries that are sure to bring about conversation. Ethics, funding, personnel, customer service, and regulatory boundaries will stimulate conversation. The way to get the conversation moving is to use a form of problem solving that Kepner– Tregoe taught in the late 1960s,2 is and is not. As in, “this example is part of the playing field, and that means that this example is out of bounds.” Let’s use new business development as an example.

Figure 3.6 Fast decision making on a playing field

One of my clients was making plans for how to work inside of a new industry segment. Their business is finance, and this industry segment looked promising, but as one of the reps pointed out in the planning session, some of the deals “have a little hair on them.” The group nods their heads in agreement, which leads the underwriting representative to push back asking why they should dedicate any resources to business that might be unsavory. The conversation went south as examples of good deals and bad deals bubbled up and we drifted from fact to anecdotes as debate centered on whether or not a customer was worth pursuing. I walked to the front of the room and drew the field of play, putting “good prospect?” on the top line, then writing “is” in the middle of the field, and “is not” outside the four sides of the field.

“If customer service is defined as the level of service you give to customers, someone give me an example of when a deal is not what you want, a service that you won’t provide,” I said. The underwriter came up with an example of a medical practice with files marked with the wrong Medicare codes, requiring more steps to underwrite the asset. “If that’s not what we want, a practice that can’t code correctly, the opposite should be inside the field of play, right? We should be okay with a medical practice that only occasionally uses the wrong codes.” I write “wrong coding” outside the field, and “correct coding” inside.

“That’s not true. We can’t accept any wrong codes. If we find one instance we need to check all their records, and that’s a lot of work too,” he said and debate continued.

The discussion moved away from random anecdotes about the past to defining the kind of customers they want in the future, within the strategic vision set by the leadership. This order of events, the small group setting the vision, the larger group setting the plan, and structuring conversation with the playing field metaphor, results in discussions about how you want your people to behave going forward. It helps the planning team make decisions that fit the strategic vision.

The speed of the planning sessions relies on a clear vision of the future. There can be no more debate about where you’re going, however we welcome robust discussion about the best way to get there. The best way for your company’s unique size, resources, and disposition. The planning day is all about how we make the future happen inside of the constraints of our organization, financially, service wise, ethically, and legally.

Speeding Up Decision Making

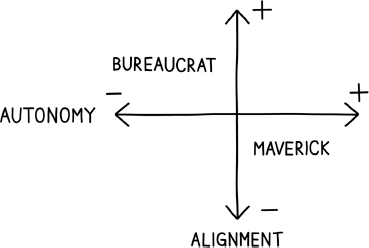

This is a good place to talk about increasing the speed of decision making in your organization. The speed of your people’s decisions is not dependent on a quirk in their personalities. Ted doesn’t make decisions faster than Mary because she’s more cautious and he’s more carefree. Their daily decisions rely on the interaction of two forces: autonomy and alignment.

Autonomy comes from the leadership team. We’re defining it as self-reliance, self-rule, or independence. It’s earned over time. The more your people are given the autonomy to make decisions without direction from above, the faster decisions will be made.

Alignment also comes from the leadership team. We’re defining it as positioned or arranged in line with the strategic vision of the company. It’s a communication issue. The more your people are aligned with the strategic vision of the company, the better their decisions will be. Let’s look at Figure 3.7, autonomy and alignment.

When we bring up the Ted and Mary examples, the first thing most people think of is a Ted with high autonomy and low alignment. The prima donna who asks for forgiveness and not permission. We find him in sales, out shaking trees and making things happen. When we think of Mary, we put her in high alignment and low autonomy. The bureaucrat that knows what the strategic vision is, understands exactly what the playing field is, and hides in the middle of it, not wanting to make the wrong call.

Figure 3.7 Autonomy and Alignment

The way to speed up decision making is to move both Ted and Mary into the upper right quadrant. Mary will make more decisions, faster, when she feels that she has the autonomy to make those calls. She benefits the most from understanding her strengths and applying them to the tasks at hand. Ted will make better decisions with the same speed when he knows the playing field boundaries. He benefits the most from understanding the clear vision of where he needs to be and when he has stepped over the line.

They are rudimentary examples, for sure, but they illustrate the importance of a strong strategic vision. The fewer people who decide the vision, the stronger it is, and the clearer it is communicated, especially in mid-sized companies.

Reviewing Strategy and Planning

Working at a big bank, one element of their planning that translates well into smaller, nimbler organizations is the regular use of re-forecasting. Strategy requires a quarterly review with the core leadership team and those meetings are controlled with a series of questions couched in the future, just like the initial exercise.

• What, if anything, has changed with technology?

• What, if anything, has changed with competitors?

• What, if anything, has changed in our current resources?

• If we had to draw it up again, do we still think our first step back from the future is what we’ll need to make the vision come true?

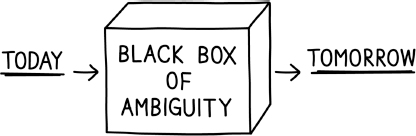

These questions are simple starters, and when the leadership team prepares for them ahead of time, the quarterly strategic vision meetings don’t take long to complete. Like a golfer on a long par five hole, we need to be able to describe what the hole looks like and what the green will look like, but its exact pin placement and the slope of the green are fuzzy ideas. I like to use Figure 3.8, the black box of ambiguity to illustrate this point.

Figure 3.8 The black box of ambiguity

We know where we are today, we know where we want to be tomorrow, but the in-between is open. We don’t have the visibility there. Your quarterly strategic vision meetings are to check that you still have the destination clearly in mind.

The planning checkups are different. To stick with the golfer on a long par five analogy a little longer, the planning checkups are as detailed as the pre-shot routine before teeing off. We know where the green is and that the hole is four-and-half inches in diameter, and right now that golfer is concerned with getting a good start on the hole. The wind, the hazards, his standing in the foursome’s betting, whether to use a draw or fade, and so on. The monthly planning sessions are a place to make adjustments. As my banker friends used to call it, re-forecasting. Let’s take what we’ve learned in the last 30 days, and think about adjustments that need to be made. Let’s think about ways to lock in activity that will result in momentum down the road, and let’s consider if our metrics are still relevant.

The way we do that is by first, not doing what I see happen with most strategic plans. I ask to see it in order to ask about progress toward the goal, and I’m met with a look of, “Hmm, where did I put that?” It’s generally in a tabbed, three-ring binder, and it looks like it hasn’t been touched since the last time someone was in asking about progress. Here’s the thing you know but is worth bringing up right now. Every step you take into the future, changes the future.

We use this simple graphic to orient our conversations with clients. Figure 3.9—past, present, future.

Figure 3.9 Timeline to orient conversations

The past is perfect in this sense. Our financial team can look back and tell us exactly what happened and we can build a story about why we think it happened. That’s the beauty of the past, and it should help us make decisions in the future. This is why we encourage our finance teams, our marketing teams, and our sales teams to collect as much data in a usable format as possible. It represents the past and it’s our only perfect information.

The present is where we make decisions. Day to day. It’s where the past meets the future. It’s the black box of ambiguity. It’s where, my old mentor would say, “We simply need you to do the right thing, most the time, to get to where we want to go.” When we make the decision, it’s informed by the future, but once it’s been put into action, the results are part of the past. Planning sessions are all about the decisions we’re making today.

For planning and re-forecasting we encourage a simple format, repeated every month, because repetition aids communication. We use the timeline to stay on track.

• What did we think was going to happen this last month? (our old predicted future)

• What happened last month? (our actual results)

• What do we want to happen next month?

The planning team consists of all departments working toward the goal, so all areas of the company are represented. This isn’t the place for an airing of grievances, it’s the place to talk about what’s happening, framed as, here’s what I wanted to happen, here’s what happened, and armed with that new information, here’s what I want to happen before the next meeting. Each department should be working on one main objective that cannot be completed in a month. If they think it will be completed during the month, they get to add a second objective to start on.

We do it this way because meetings in small companies can be a drag. Everyone kind of knows what everyone else is doing, but the planning meetings serve two purposes. It reminds everybody of the big target and the steps to get there and it reminds everyone that single, important priorities moving forward a mile, add up faster over time than multiple priorities moving inches ahead.

If those are the two big purposes, the side benefit of these meetings is that they are places where managers can actively learn how to manage their own people. As a new manager sitting in a room of seasoned managers, some making progress, some not, they see firsthand that everyone needs to know where the company is going, how to prioritize, and how to adjust.

Willa Cather, the great novelist, sums up how important this ability to hold a vision of the future is through the voice of one of her characters, Captain Forrester, the old road builder, in her novel, A Lost Lady.

“Well, then, my philosophy is that what you think of and plan for day by day, in spite of yourself, so to speak—you will get. You will get it more or less. That is, unless, you are one of the people who get nothing in this world. There are such people. I have lived too much in mining works and construction camps not to know that.”

He paused as if, though this was too dark a chapter to go into, it must have its place, its moment of silent recognition. “If you are not one of those, you will accomplish what you dream most.”

“And why? That’s the interesting part of it,” his wife prompted him.

“Because,” he roused himself from his abstraction and looked at the company, “because a thing that is dreamed of in the way I mean, is already an accomplished fact.”

Cather captures the essence of strategy and planning in that passage. A clear destination, continuously illuminated, will draw you to itself. That is the spirit of the old West and that’s the spirit your company needs to accomplish your strategic vision.

My aunt put it another way, she said, “Gregory, all prayers are answered, just not in the exact same way or exact same time frame as we ask for them.” I always thought that was loose enough to describe any result, but I get her point and I want you to keep it in mind for your own strategy and planning because it’s the first step in unleashing your people’s hidden growth potential.

Show them where you’re going.

Remember

• Strategy and planning are two different things.

• Set your strategy in less than a day.

• Planning is a group activity on how to get there.

1 Weiss, A. 1994. Best-Laid Plans: Turning Strategy into Action Throughout Your Organization, xi. Las Brisas Research Press.

2 Kepner, C., Tregoe, B., 1965. The Rational Manager: A Systematic Approach to Problem Solving and Decision Making. McGraw-Hill.