CHAPTER 5

Where Are All the New Ideas?

BACK IN THE 1980S, I worked for a design firm called Studio-Works in New York. The firm specialized in museum and exhibition design. We did some really interesting projects, including the look of the Statue of Liberty Centennial and the design of the Staten Island Children’s Museum and the P.T. Barnum Museum. Our office was a loft on 27th Street in the center of the flower market on New York’s west side. I was fresh to New York, “right off the turnip truck” as one local told me when I asked him if Broadway ran diagonal to 5th Avenue.

The first time I walked into the Studio Works loft, it exuded everything I had imagined about the edgy side of New York design. After getting off a rickety elevator on the top floor, the door opened to an expansive sunlit loft space with twenty-foot ceilings, drawing tables everywhere, artwork on the walls, and design sketches neatly arranged on a large conference table in the middle of the floor. It was still a couple of years before the first Macintosh Plus computer would grace design firm offices, so all the work was handmade, pinned on the walls, and spread around the room in movable parts of type and image. The back wall was lined with tall windows that pivoted open, which helped offset the lack of air conditioning in the hot summers. The most striking sight was the expansive presence of the Empire State Building seven blocks to the north. We were nestled in the epicenter of the design world.

Keith Godard, one of the firm’s partners, is a highly regarded British designer who’s been living in the United States since the 1970s. He’s an icon in the graphic design field, and I was lucky enough to have him as my first boss, my mentor, and the person to whom I looked for design guidance. Keith’s work flowed into his friendships with the Kennedys (I helped him design the invitations for Caroline and Eddie’s wedding), James Stirling (one of Europe’s most significant architects), and composer Philip Glass.

I was fascinated by how Keith designed. In art school, I had learned about design sensitivity from the Swiss-inspired Basel designers who are disciplined, austere, and insistent that form follows function. But Keith came from the opposite direction. British designers are more expressive and conceptual. Their attitude is that almost anything goes in design, and they create some fantastic work. Coming from the carefully considered world of Swiss design, I had to get used to the idea that Keith designed with abundance. He operated by a principle contrary to that of German design icon Walter Gropius, whose mantra was “Less is more.” Keith’s mantra was, as he often said, “Less is a bore.” His designs burst at the seams. His work was about the concept, the big idea, an approach that I eventually realized extends directly into problem solving in the sales environment.

One day as I watched Keith work, I commented that one of his ideas might have had an uncanny resemblance to something I had seen before in a great piece of design. I was hesitant with my comment, concerned about saying something wrong or offending him. But instead of a hostile reaction, Keith looked at me wryly and said, “Well that must mean it’s good, mustn’t it?” With that one comment Keith offered me a bit of insight: All good ideas aren’t totally new.

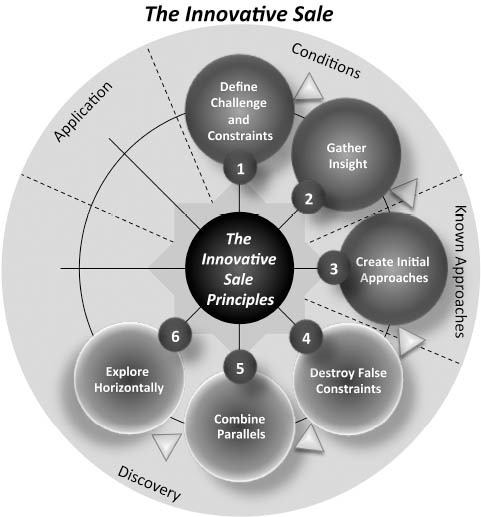

And so it is in sales innovation. One of the challenges is the belief that a good, creative strategy or customer solution has to be completely new. The pressure to innovate and draw out previously unheard-of ideas can actually stifle innovation. Innovation stage fright prevents a lot of people from even trying to go beyond the norm: “Why waste the time? I’m not creative. I’m a numbers person. I’m a good implementer. . . .” But with sales innovation, there is an abundant source of opportunity by combining “parallels” (Figure 5-1).

FIGURE 5-1. COMBINE PARALLELS AND EXPLORE HORIZONTALLY.

Step 5: Combine Parallels

Parallels are situations analogous to ours. They can come from a different company or industry. Sometimes these ideas are used in a different context or for a different purpose. In fact, parallels may not even come from business, but from other life situations. In Chapter 2 we discussed the imperative, combine unrelated ideas, including the examples of Joseph Pulitzer, Henry Ford, and Johannes Gutenberg. Each took two well-known ideas and combined them to create a third, totally novel innovation. To combine parallels in the Innovative Sale process means to put different ideas together, like pieces of a puzzle.

Doreen Lorenzo uses a process similar to combining parallels: “We use provocations to call in similarities that we’ve seen and use those to then translate into actionable items. A provocation is something that might not have anything to do with the particular topic you’re working on, but it will provoke you to think about the ideas differently.” For idea generation, Frog brings people together to think of provocations for a particular client problem. Each provocation leads them to other ideas. After awhile, the ideas can be categorized into groups, based on similarities. “It’s really interesting how it unfolds,” says Lorenzo. “It becomes a linear path and we begin to see how these ideas play into something that has value. Through the provocations, unconnected ideas begin to come together.

“Through this process, we’re trying to grow the mind to think about something differently. Businesses have an incredibly elastic memory and they always go back to what they know. It’s so absolutely scary to do something different. It’s so much easier to be gray than to be red.”

Combining parallels is an exercise in gathering more raw materials for idea development. We’re not worried about the final solution yet. We’ve defined the issue and its constraints, gathered insights, listed our known approaches, and destroyed the false constraints. Our prior brainstorming and critiquing have created a catalog of ideas from which to choose; the team can also incorporate insight directly from customers or partners and look to history, recent or not, for additional pieces of the puzzle.

Paul Johnson recalls combining parallels to work through a tenuous situation with channel partners when he was the executive vice president of sales at another company. “Over the years, we had amassed a lot of value-added resellers to take our product to market,” he says. “The name of the game was to get more distribution points, so our sales organization signed some great resellers and a lot of marginal resellers.” The typical partner program allowed them to earn a percent of the product markup and receive a lot of vendor support, like training and comarketing programs. It became a strong package of financial benefits for the reseller.

The problem, he says, was that they provided the same partner program to all resellers, regardless of their level of engagement in the sales process. They had resellers driving sales, and resellers who received leads from the company and lived off of license renewal income. It worked in the short term when they were getting the business up and running, but it was expensive and unsustainable over the long term.

According to Johnson, “There wasn’t a straight-out way to solve this.” If they decided to remove the lower contributing population of resellers and sell direct, they would take on a huge infrastructure cost of having to hire a new sales organization. Also, they could potentially scare off the good resellers who may have feared that Johnson would eventually go direct to the customer and remove them from the distribution channel. “If we came up with something on our own, it would carry a lot of risk because the resellers would assume that it was to our advantage,” he said.

So Johnson and his team talked to the resellers to understand their business priorities and sensitivities. He also put together a reseller advisory team. Instead of proposing a new program to them, Johnson laid out the situation and then posed a range of options that his team pulled together from different technology and distribution environments. None of the components alone was the answer, but they were like puzzle pieces they could put together, overlap, or break apart. They asked the reseller advisory team not to give them a solution but to propose additional pieces from their experiences.

“After a few iterations of working with them, we had some really bad combinations—like going direct for major accounts and outsourcing just the implementation and service—and some better combinations—like segmenting the reseller base by business model, mission alignment with our company, and sales potential,” he says. “We came out with a program that looked at a few major reseller segments. The resellers that didn’t fit this new program weren’t happy, but most understood our logic. But the resellers with the right alignments got a better program than they had before. It made sense for their businesses and ours.”

There are four steps to combine parallel ideas in the Innovative Sale process: look to the generations; deconstruct your challenge question; find matches that address just 25 percent of your challenge; and put the pieces together.

Look to the Generations

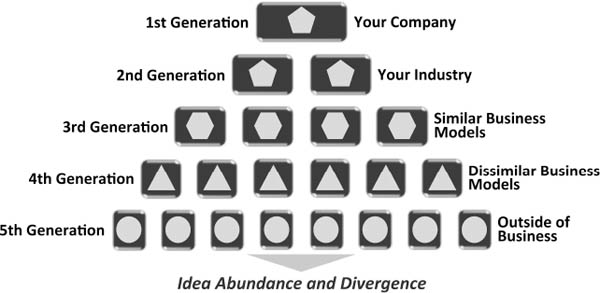

As illustrated in Figure 5-2, looking beyond your immediate environment can be the greatest source of parallels. Because each step moves progressively further away from your company and market, we refer to these steps as “generations.”

First generation: parallels within your company. Parallels within your company can be surprisingly diverse, especially if you look to the other divisions, regions, and functions. Often companies have proprietary research that can be leveraged. For example, in Chapter 4 we discussed Julie’s software company that was struggling to improve its renewal rates. When looking inside their company for ideas, Julie’s team found a program used by another division, a customer portal that enhanced customer satisfaction and earned loyalty.

FIGURE 5-2. FIFTH GENERATION PARALLELS.

Tracy Tolbert benefits from first generation parallels frequently. His company, Xerox, has almost 100 different businesses all around the world, and Tolbert’s sales organization pulls from the variety of experiences and ideas in all of those businesses: “It gives us some advantage as we create solutions for customers, because we have the ability to lean on different organizations and create solutions that may have an element of a prior solution from another business within Xerox. We’re able to come up with some pretty creative solutions.”

Second generation: parallels within your industry. Parallels within your industry include what your competitors have done or are doing. It’s likely that your competitors have addressed the strategy challenge or customer situation you’re dealing with at some point too. But remember, you don’t want to replicate their solution; you’re looking for parts of their solution that can be combined with other puzzle pieces to create a new solution.

Third generation: parallels in companies or industries with similar business models. The third generation of parallels looks at businesses outside your direct competitors that have a similar way of generating revenue. The software company in Chapter 4 struggled with customer renewals. To solve the problem, it might look for parallels in other contract-based services businesses—like telecommunications or insurance companies who depend upon high customer revenue retention—to examine how they build customer loyalty programs.

Fourth generation: parallels in companies with dissimilar business models. Parallels in companies with dissimilar business models extend the reach one step further and force a sales organization to look at solutions it may never have considered. Julie’s sales team would now look at companies that need to retain customers, but without a contract. Sources might include airlines, hotels, grocery store chains, credit cards, or even magazines. For example, grocery stores may seem completely unlike software companies on the surface and may not even be considered by the sales team. While grocery stores have a considerably different business model, many use loyalty cards that offer discounts to frequent shoppers. By examining the similarities between your business and these businesses, you may find additional parallels that will contribute to your solution.

Fifth generation: parallels outside of business. By the time you reach the fifth generation of parallels, you’re about as far from home as you can get. Once you’ve looked for similarities within every corner of the business world, it’s time to think beyond business. At this point Julie’s team might ask, “What happens outside of business to keep people loyal to something?” Examples may include sports teams that create fan bases and nonprofit organizations that rely on sponsorships from loyal donors year after year. Even certain aspects of family or cultural allegiance can lend some clues. How do groups stay loyal, decade after decade, to a particular tradition?

By the fifth generation, at the bottom of the tree diagram in Figure 5-2, you’ll have a pool full of parallels. The ideas increase in divergence the farther down the tree you travel. Both the abundance and the range of ideas create a plethora of components. Some combinations won’t make sense, but others, as you’ll see, can become the components of an Innovative Sale.

Deconstruct Your Challenge Question

First, we stated our challenge, and then we gained insight by asking questions in the first steps of the Innovative Sale process. We dug beneath the surface of the problem to understand its underlying causes. Now that we have an inventory of possible parallels from the five generations, we can break our original challenge question into parts to begin matching and combining. The idea here is to find potential parallels for each part of our challenge.

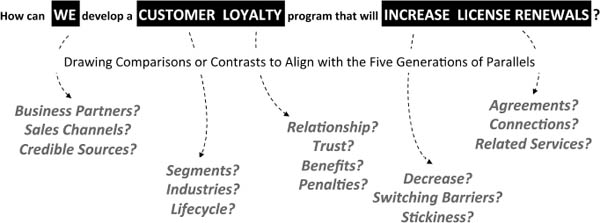

For example, let’s take the software license renewal challenge and break it into parts. Julie defined the challenge as, “How can we develop a customer loyalty program that will increase license renewals?” As shown in Figure 5-3, we can break this question into parts. I’ve emphasized the important elements in capital letters: “How can WE develop a CUSTOMER LOYALTY program that will INCREASE LICENSE RENEWALS?”

FIGURE 5-3. FINDING PARALLELS IN THE CHALLENGE QUESTION.

Find Matches That Address Just 25 Percent of Your Challenge

Now we have something we can work with at a different level than the original challenge question. Just by looking at the pieces of the deconstructed challenge, we can look for parallels that might match just one part of the challenge. Our odds go way up that we’re going to find some innovation components that will change our thinking. For example, as shown in Figure 5-3 and explained next, take each part of the challenge question and look for parallels.

“How can WE develop . . . ”: Should your company actually develop the program itself or turn elsewhere for help? For the software company, Julie and her team might look at how other organizations use business partners, sales channels, or other credible sources to develop or implement programs. Looking for parallels here could lead them, for example, to leverage the talents and resources of their software reseller partners.

“. . . a CUSTOMER . . .”: How do other organizations define their customers? Maybe Julie’s team shouldn’t try to solve the renewal problem for every customer. Perhaps there are parallels for how other organizations have focused on specific customers, customer segments, or industries.

“. . . LOYALTY program . . . ”: Isolating the “loyalty” component can create a number of parallels to how organizations create relationships and foster trust to build loyalty.

“. . . that will INCREASE . . .”: The element of “increasing” suggests parallels to growing quantities or—just the opposite—decreasing quantities. So in applying parallels we might look for examples of not only increasing loyalty but also decreasing departure. Decreasing departure could generate parallels around disadvantages of leaving a situation, raising switching barriers, or creating more stickiness in the relationship or product.

“. . . LICENSE RENEWALS . . .”: Focusing on “license renewals” suggests parallels to categories of agreements in general, and specifically contracts requiring people to stay with someone or something. Julie’s team might also look for parallels beyond renewing an agreement for a product to renewing an agreement for other related services that could increase loyalty for the main product. For example, what if Julie’s company found that customers really valued a related professional service they receive from her company, but the most economical way to get that service was to also maintain their software license contract? Julie would shift the parallel to finding related services that increase retention of core services.

Put the Pieces Together

Now it’s time to begin mixing and matching the many fractured pieces of our puzzle. Take the ideas generated by examining parallels and put them together to test their logic and potential application. Combining parallels may not be as difficult as you think. For one thing, our brains are hard-wired to find patterns among seemingly unrelated factors. As humans, our brain is our most vital defense mechanism, and as we evolved it was necessary for our brains to be on constant guard for predators. Hearing a stick break and then watching a lion jump out of the grass are two seemingly isolated events, until you watch one eat your neighbor, and then you identify a really important connection.

Scott Huettel, a Duke University professor and director of the Duke Center for Interdisciplinary Decision Science and the Center for Cognitive Neuroscience, has conducted research on the brain’s quest for patterns. According to Huettel, “The human brain really looks for structure in the world. We are set up to find patterns. . . . It allows us to extract regularity from the world.” The same trait explains why some people are superstitious, explains Huettel. If you wear a red hat and your team wins the football game, you might identify a pattern and have a really strong urge to wear a red hat the next time your team plays.

While there’s no evidence that superstitions can influence the outcomes of sporting events, this brain adaptation comes in handy when considering innovative ideas. Our brains seek to make sense from unrelated concepts.

Combining parallels is the start of horizontal idea generation. You may be amazed at the ideas you can now easily generate using this technique. Lay out the parallels and see what new solutions come to mind. We’ll go into horizontal thinking in the next step of the Innovative Sale process.

Step 6: Explore Horizontally

When I worked with Keith Godard at StudioWorks, one of our projects was redesigning the P.T. Barnum Museum in Bridgeport, Connecticut. P.T. Barnum originally opened the American Museum in 1842 in lower Manhattan. For years it fascinated tourists with its 850,000 curious exhibits including a flea circus, a loom run by a dog, the trunk of a tree under which Jesus and his disciples sat, a pair of argumentative conjoined twins, a mermaid, and Tom Thumb. Barnum met Charles Stratton, aka Tom Thumb, in 1842 when Stratton was a four-year-old boy and had already reached his full height, at just twenty-five inches. Barnum immediately hired this young boy and billed him as “General Tom Thumb, Man in Miniature,” as an attraction at his museum. Stratton (as Tom Thumb) became wildly popular, attracting thousands of people to the museum. Barnum even toured Europe with Stratton, including an audience with Queen Victoria. Years later, Stratton married Lavinia Warren, also a dwarf who had been hired by Barnum. Their wedding, held at New York’s Grace Episcopal Church, was followed by an elaborate reception at the Metropolitan Hotel where Barnum charged $75 to the first 5,000 people to attend. Reportedly, Charles and Lavinia received their guests while standing on top of a piano. Throughout his life, Stratton was one of Barnum’s most-loved attractions.

In 1893, after both Stratton and Barnum had died, Barnum’s museum moved to Bridgeport, Connecticut, where it still stands. Stratton’s artifacts, including some of his clothing, photographs, papers, the carriage in which he and Lavinia rode immediately following their lavish wedding, and many other personal items from his home became available for the museum to display.

In the 1980s, Keith Godard, Hans Van Dijk, and Stephanie Tevonian of StudioWorks were hired to redesign the museum, including the circus displays, artifacts from the famed opera singer Jenny Lind, and, of course, the Tom Thumb exhibit. I was on the team and privy to their thought processes as they considered the many ways to display the personal possessions from Tom Thumb’s famous life, including carriages and furniture, clothing, photos, and paintings. Our original challenge question for this project was, “How can people view Tom Thumb’s life and his artifacts?” We began with some conventional options. The simplest way to design that exhibit was a traditional museum approach, which is to put all of the items in cases, put them on the wall, and rope it off so people wouldn’t get too close. But just by looking at a picture of Tom Thumb, it was hard to grasp what life would have been like at his size. We didn’t want to just put these things in cases; we wanted people to experience Tom Thumb, to view his life. We thought, “What would it be like to look at the exhibit not as a full-sized tourist, but as if you were Tom Thumb’s size? Let the tourist see daily life as Tom Thumb would have seen it.”

So we built a Tom Thumb house out of glass, and we cut out an aisle for people to walk through. The floors for the house, other than the aisle, were raised several feet, so that when visitors walked though, the floors hovered somewhere around waist level, as though they were about twenty-five inches tall. The furniture was “Thumb-sized,” and we placed likenesses of Tom and his crew throughout the house, as if they were standing there. So walking through the house, the visitor saw everything from Tom Thumb’s vantage point. It was a paradigm shift.

The team used horizontal thinking. We came up with a range of ideas, from traditional to ridiculous. On the traditional right side of the scale, we could have used glass cases: an austere museum style to display these old and valuable artifacts, putting them piece by piece on the wall so you could observe each one in isolation. Or, we could have created a classic nineteenth century museum style with dark paneling and a musty feel reminiscent of Barnum’s original American Museum.

On the opposite side of that scale, we could have created a very open and accessible exhibit, allowing people to try on Tom Thumb’s clothes and shoes, leaf through his papers and photographs, or step into his tiny carriage. Of course, this would have quickly destroyed the artifacts. Or we could have created super-scaled clothing for people to try on and furniture for people to sit in, making them feel as if they were small in an oversized world. Eventually, we hit on the right idea and built an exceptional exhibit.

Horizontal thinking creates an abundance of ideas across a divergent range of options. “During the schematic design phase, developing a diverse range of options is essential,” says William Chilton. “Our buildings can be very complicated design problems, and there are many factors to consider. To think you’re going to step up to the plate and on the first pitch hit a homerun is unrealistic—it can happen, but not very often.”

For Chilton and his team, settling on the right idea takes dialogue, debate, and reflection: “Great ideas come from lots of different places. It could be from travel, or being inspired by a piece of art. Some ideas coalesce in a specific way for a specific client. It can be the development of a series of ideas that you’ve been noodling for many years.”

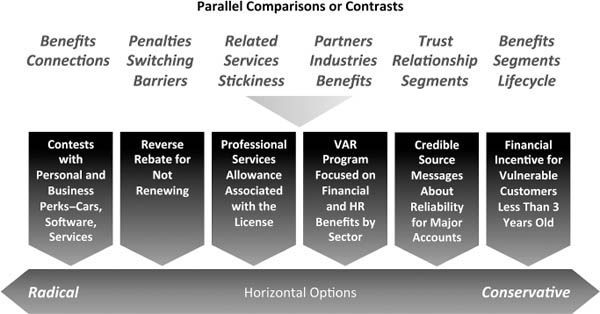

As the ideas come together through combining parallels, we can begin to evaluate them on a right (conservative) to left (radical) scale that ranges from the modest to the moderate to the most far-out ideas.

Using the example from Chapter 4, we can explore how Julie and her team might have developed a range of ideas to design a customer loyalty program and increase their renewal revenue. We can actually draw a line, placing the most conservative of those ideas on the right side and the more far-out on the left, as illustrated in Figure 5-4.

FIGURE 5-4. COMBINING PARALLELS INTO HORIZONTAL OPTIONS.

By combining parallels and positioning their ideas from right to left, they might have considered the following:

![]() Create a program that focuses on a certain group of highly vulnerable customers—those who have been with the company for less than three years—to offer them a financial incentive to renew (very conservative).

Create a program that focuses on a certain group of highly vulnerable customers—those who have been with the company for less than three years—to offer them a financial incentive to renew (very conservative).

![]() Enlist a credible, verifiable referral source to help build loyalty within certain customer segments like major accounts, based on the trust and reliability of the company’s products.

Enlist a credible, verifiable referral source to help build loyalty within certain customer segments like major accounts, based on the trust and reliability of the company’s products.

![]() Use a loyalty program through another company. For example, a software value-added reseller (VAR) could implement a loyalty program that emphasizes the financial and human resource benefits of renewing.

Use a loyalty program through another company. For example, a software value-added reseller (VAR) could implement a loyalty program that emphasizes the financial and human resource benefits of renewing.

![]() Change the focus from the software product to other services. Julie’s team could create a VAR partner program that emphasizes the professional services allowance that comes with being a customer, not the renewals of the core software product. This program would be based on the other related technology services that the company provides at a discounted rate along with a software renewal. That changes the paradigm.

Change the focus from the software product to other services. Julie’s team could create a VAR partner program that emphasizes the professional services allowance that comes with being a customer, not the renewals of the core software product. This program would be based on the other related technology services that the company provides at a discounted rate along with a software renewal. That changes the paradigm.

![]() Develop a program that creates financial penalties for not renewing. They could offer a reverse rebate: A customer loses money if it doesn’t renew its contract.

Develop a program that creates financial penalties for not renewing. They could offer a reverse rebate: A customer loses money if it doesn’t renew its contract.

![]() Enter all renewing customers in a drawing for a major personal or business benefit such as a new car, five years of free software subscription, or one year of free professional services.

Enter all renewing customers in a drawing for a major personal or business benefit such as a new car, five years of free software subscription, or one year of free professional services.

Your options should move from the conservative to the far-reaching. While your ideas on the right may feel common, the ones on the left may be completely unrealistic, beyond the scope of what your customer would do. If the ideas don’t feel that way, you’re not pushing far enough. You should have ideas that you have to trim back. As you develop ideas along a horizontal axis, ask, “Is the range wide enough?” If not, broaden your thinking and get crazier. Horizontal thinking is not difficult, but it requires more than just reacting with the same old ideas. Once you’ve generated a good range and abundance of divergent ideas, it’s time to go into vertical development.

INNOVATIVE SALE ACTIONS

![]() Map out the five generations of parallels, beginning with what’s been done in your own company and ending with any similar situations outside of business.

Map out the five generations of parallels, beginning with what’s been done in your own company and ending with any similar situations outside of business.

![]() Deconstruct your challenge question; examine each word to see what parallel ideas might be found in the nuances of your question.

Deconstruct your challenge question; examine each word to see what parallel ideas might be found in the nuances of your question.

![]() String together all the parallels that make sense, and see what the picture begins to look like.

String together all the parallels that make sense, and see what the picture begins to look like.

![]() As you string together the parallels, focus on creating a range of ideas, from conservative to completely unrealistic.

As you string together the parallels, focus on creating a range of ideas, from conservative to completely unrealistic.

![]() Check to ensure you’re pushing the thinking far enough. If the ideas on the farthest left of your scale are still appropriate, push harder. The idea is to think creatively, and potentially use a piece of the crazy idea, not the whole thing, in your final solution.

Check to ensure you’re pushing the thinking far enough. If the ideas on the farthest left of your scale are still appropriate, push harder. The idea is to think creatively, and potentially use a piece of the crazy idea, not the whole thing, in your final solution.