CHAPTER 6

The Attraction of Rejection

FRANK, A SALES REP for a paper company, crossed the parking lot and headed toward the customer’s building. It was a humid Los Angeles afternoon, peppered with the grit from the factories around him. As he entered the building, he could hear the sounds and feel the vibrations of the printing presses. Walking down the expansive, gray hallway, Frank passed a long window that was showcasing the printing room where two enormous Heidelberg presses churned out colorful brochures so fast they became a solid blur. The scent of the ink and the bustle of the pressmen reminded him of his decades in the business and how much he enjoyed working with customers. Frank paused and glanced through the window at the machines, mesmerized by their clean automation. He loved the power, the precision, and the specifications.

A true left brainer, Frank hadn’t grown up in sales. In fact, he had been a truck driver for the paper company for twelve years, delivering pallets of printing paper and packaging supplies to the company’s customers all over southern California. Logical and analytical, Frank knew every mile, every route, and every cost calculation. He understood product and logistics, margins, carrying costs, and the finances of the business. Because of his knowledge, several years ago he was promoted into operations and, after further success, into sales. Frank still operated analytically, though. When making a sale, his angle was always the financial benefits he could offer to the customer, mostly by cutting price.

But, over the past couple of years the company had changed how it thought about selling. It could no longer compete on price alone. Frank’s sales manager constantly reminded the team, “We’re already too much of a commodity. Think of solutions for the customer.” But, despite his best intentions, transforming his personal sales style was not something Frank could do on his own.

Frank was not alone, and his company’s leaders recognized this. They also realized that increasing sales performance wasn’t about more sales training or new sales techniques; they had to change the way they thought about customers. They began to demand more ideas, and they incorporated an idea generation process into their work. Frank, uncomfortable with getting beyond the numbers, approached the process with some hesitation. But it was logical and easy to follow, and Frank soon felt at ease working with his team through horizontal solution development. He realized that it was like riding a bike; it wasn’t as hard as he thought. Soon it became natural for him to think that way.

But Frank’s new solutions didn’t always sit well with his conservative customers who had a difficult time accepting his ideas. For example, six months earlier Frank had suggested to an upscale stationery designer that they partner with the recycling arm of his company and purchase only 100 percent recycled paper. Unfortunately, Frank’s customers hadn’t seen their environmental image as a primary concern, and they were shocked by Frank’s many references to the incredible work his company did recycling waste paper. Frank hadn’t given them any context for this proposal; in fact, he had proudly announced it within the first three minutes of their meeting. The stationery customers declined Frank’s innovative idea.

So his team began asking, “How can we get the customer more comfortable with some of these ideas? Can we do a better job telling our story and bringing customers along mentally and emotionally, instead of surprising them with something drastically new?”

Frank snapped out of his reverie and jogged down the hall. He caught up with his team just in time to enter the small conference room and greet his next customers—the vice president of operations and director of purchasing of the printing company—who, while polite, clearly had a lot on their minds. More than 50 percent of this company’s revenue came from a large insurance company, which had recently cut its orders by one-third in order to save money. They had chosen to decrease the amount of material printed to save costs, rather than cut the quality of the final product. Today, Frank wanted to propose several ways the printer could recover those orders, including a line of high-quality coated paper that actually cost less than the uncoated paper they currently used for the insurance company.

He also wanted to suggest ways the printer could partner with the paper company and other customers to combine print runs and setup costs.

Frank noticed the vice president glancing at his watch for the second time in two minutes. He didn’t have a lot of time to listen to a sales pitch. This time, instead of immediately proposing a new idea, Frank began his story with the main problem: the customer’s challenge of meeting the demands of its most important customer. Frank described how he considered conservative ideas, such as dropping the paper’s price. But the paper company wasn’t able to lower the price enough to meet the insurance company’s cost constraints. Frank and his team had also considered printing the insurance materials on higher-quality, more expensive paper to recoup some of the lost revenue. But, of course, the customer would not have been on board with that solution.

Finally, Frank described the line of coated paper. The paper was high quality, and had the appearance of costing more than the uncoated paper. Frank’s company was able to provide this paper to the printer at a lower cost than the uncoated papers and pass this cost savings along to the insurance company. The printer could also decrease its costs by combining print runs with some of its other customers who would use that same paper, offsetting the fixed costs of setting up individual print runs. These two solutions together would make room in the insurance company’s budget for a larger printing order. While it seems like a simple solution on the surface, it was an approach that the printing company had never discussed with Frank.

Because Frank took the time to explain how he had developed the solution and why it was appropriate, the printer’s reaction was dramatically different from the dismissive one of the stationery designer. As he discussed their many ideas and the logical approach to their final conclusion, the solution became apparent to the customer. It wasn’t just Frank’s idea; it was how he communicated it.

Frank received a warm reception from the customers, whose time constraints seemed to melt away as they learned about Frank’s ideas for how they could engage their own customers. Frank had turned the new ideas into a logical story, and then into the Innovative Sale.

Frank’s success with the Innovative Sale depended not just on good ideas, but a solid presentation through which to communicate them (Figure 6-1). As he had discovered in the past, surprising the customer with a radical idea won’t fly. The surprise of the event can distract a customer from genuinely evaluating the idea.

Communication can begin at one of two places; If you’re codeveloping a solution with a customer, it begins immediately. While working together, you and the customer share ideas along the path and have fewer surprises at the end. If, however, you are unable to codevelop the solution, either due to lack of time or lack of relationship with the customer, you can still bring your customer along on the adventure to an innovative solution. But before the final pitch, it’s time to zero in on the correct solution.

Step 7: Develop Vertically

When I was in art school, before every painting, I’d put pencil to paper and sketch my designs. I would have never dreamed of going straight to a blank canvas with a paintbrush covered in a fairly unforgivable color of oil unless I was certain of what I was about to do, and had at least a good idea of what the final picture would look like. I’d sketch many, many times the various ways I wanted to express my vision.

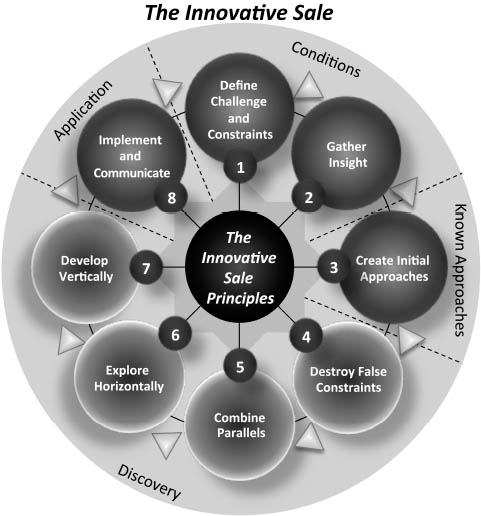

The Innovative Sale process works in a similar way. In horizontal idea development you sketch your ideas. You’re not worried about how the final solution will look; you’re interested in considering many possibilities, practical and impractical, and turning your ideas left, right, upside down, and backward just to see what will happen. But when it’s time to develop vertically, you’re ready for the canvas, the paintbrush, and those oil paints (Figure 6-2). It’s time to get serious about your solution, the practical ways it can work, and the details that can make or break it in the end.

FIGURE 6-2. DEVELOP VERTICALLY AND IMPLEMENT AND COMMUNICATE.

Vertical development entails selecting the best ideas, and then digging deep down to build out the solution. Pick the finalists from the list of horizontal ideas that will fit the customer situation. You don’t yet have to settle on one. You may select two or three to share with the customer, depending on how willing the customer is to explore options. In the design world it was common for us to pitch several alternative ideas because we knew it was a whole lot easier for clients to accept our recommendation if they had a chance to reject another option.

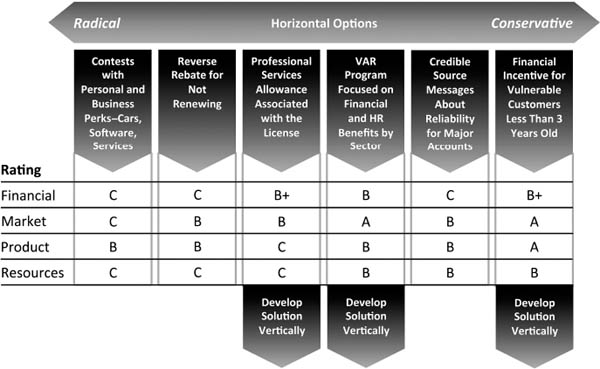

To help narrow down the pool, you can return to the customer challenge dimensions from Chapter 3 and use those four dimensions—financial, market, product, and resources—to assess each of your solutions. Evaluate your ideas according to the scale in Figure 6-3. What follows is a more detailed explanation of the four assessments.

Financial. Rate each of your solutions on the financial dimension. If your customer implements this solution, what kind of financial return might there be in terms of revenue, profitability, cost, productivity, or any other important financial measure?

Market. “Market” and “end-user” may be synonymous here. Examine each of your solution options from a market perspective (if a customer applies it to their customer) or from a user perspective (if the customer applies the solution internally). When thinking of market implications, ask how this solution will affect your customer’s customers. When thinking of user implications for internal application, ask how the solution will affect your customer’s internal user groups.

FIGURE 6-3. TESTING YOUR SOLUTION.

Product. Judge each alternative with the customer’s offering in mind. How will this solution impact the sale of the product? If the customer is addressing an internal situation, rather than an external customer situation, think about product as the application of the customer’s solution.

Resources. Consider how this is going to match up to the customer’s resource objectives to make things happen or get things done. This may refer either to resources that the customer needs to work externally with its customers or to the resources required for internal operations.

Because we used the customer challenge dimensions to define the problem in the beginning of the process, these dimensions offer the perfect standard against which to test your divergent ideas. The resulting grade helps you objectively evaluate a range of creative ideas and build consensus among the team. Now you’ll see which of your sketches have potential, and which should be filed away for later use.

Many of my best ideas have been met with rejection. Not only is it important to accept and work with rejection from teammates, but also it’s vital to expect and accept the rejection of your ideas from the customer. Rejection is just part of the creative process. In fact, the bigger the idea, the more rejection you should expect. There’s another element, too: Sales innovation needs leadership with vision. The perfunctory purchasing manager will often reject a new idea out of aversion to any departure from the norm. That person may feel responsible for the ultimate success or failure of the solution, and wants to only deal with the tried-and-true solutions. If the customer’s company has an innovative leader, the customer will likely be open to innovation. Be on the lookout for enlightened visionaries and beware of the protectors of the status quo.

Allen Kay explains, if there’s a lackluster leader, people may fear introducing new ideas. “No matter what the leadership is, they have to have the guts to move stuff up the chain of command,” says Kay. “And in large corporations, many people don’t have the guts to do that.” One of the first clients Kay worked for was a large insurance firm. Kay was working with Lois Korey at the time, and she told him (paraphrased), “It’s impossible to sell this client anything. Everyone is so frightened that they won’t approve anything beyond the lowest level. They’re afraid that if they approve something and the boss doesn’t like it, they’ll get in trouble. Therefore, nothing ever gets beyond the first level.” This was a terrible problem for Korey and Kay, because, as Kay says, “We were presenting really wonderful, wonderful stuff and it was going nowhere. No one was benefiting.”

But Korey had a creative idea to solve this problem. Kay says, “Lois had a stamp made that read, ‘I disapprove of this ad.’ So, we then presented our ideas to the assistant brand manager. He said, ‘No, I can’t approve this.’ Lois said, ‘Okay.’ She took out the stamp, stamped the ad, and said, ‘Would you sign it please? The agency has a new policy. When somebody disapproves of something, they sign it and it goes to their boss, so the boss knows what they disapproved.’ The guy wouldn’t sign it.

“On the very day we presented that poster, it went all the way to the top—approved—and saw the light of day.”

In the best customer situations, you’ll meet with people who are willing to say, “Yes, I like this idea. This is cool.” If you have a leader who likes cool ideas, it’s much easier to gain acceptance. If the people up and down the line have the guts to approve it, innovation gets through. The chain can break anywhere along the line, but if belief in innovation doesn’t come from the top, the sales rep’s job is that much harder.

The truth is that the people rejecting your ideas probably have some power. It could be your customer rejecting your proposals, or it could be a team leader. Because these people have power, their rejection is going to sting a little more. But you still have to consider the validity of their statements without getting emotional about it. Determine whether you’re going to press on if you think your ideas are defensible; or if you’re going to accept what they’ve said and modify your ideas based on their input.

While Manpower Group promotes a culture that encourages new thinking, it’s not willing to implement every new idea. Doug Holland sees rejection, often because their industry can’t absorb the cost of mistakes as easily as others: “It’s very challenging, especially in a low-margin business like ours, to feel really comfortable saying it’s okay to make a mistake.” So Manpower Group asks for a reasonable risk assessment before innovative ideas are approved or rejected. “What I see the most is not so much that ideas get rejected because they’re threatening. An idea might get rejected because the proof of statement isn’t behind it. We want the sales person to effectively articulate the predicted outcome and the benefits to the organization. Sometimes a creative solution might require a different type of investment up front. The rep needs to be able to show if we do this, here’s the ripple effect and here is the return based upon our best estimates.

“When you have a good idea in this company, and you can show what the endgame is going to be and you can articulate it really well, our leadership will go along with it. When they don’t go along with it is when you can’t articulate what that benefit is.”

If you’ve codeveloped your solution with the customer, you’ve certainly shared the range of idea components throughout the process. There’s little room for surprise in something they’ve codeveloped, so the chance of rejection drops considerably. In the absence of shock value, the customer can evaluate the idea on its own merits instead of being distracted by how different it may be.

Even so, depending upon your industry and sales process, getting final approval from the customer can be tenuous and surprising. “If you don’t get that kind of support and buy-in at the highest level, you’re not going to be successful,” says Tracy Tolbert. “I’ve seen a handful of deals in my career that you think you have the support you need, but when your sponsor takes it up to the top for the final approval, the final signature of the CEO, or even the board—it turns out you did not have the support there that you thought you had. And you’ve spent a lot of time and energy. I’ve seen a lot of naive salespeople who think they have the buy-in from the buyer, but the reality is the buyer didn’t have permission to buy. That’s the challenge.

“Don’t underestimate the toll a potentially large change might have on the decision whether or not to even implement the solution. The solutions that we provide are typically big and they’re changing the internal workings of an organization. We can show great value, we can show great savings, we can show increased delivery, response times, and all of the things that we measure, and a client can still just say, ‘You know what, we can’t do it.’ ”

At this stage, it’s also important to do customer or end-user testing to get their perspectives. As you commit to a solution, you have to make sure it will align with what the customer will need.

Step 8: Implement and Communicate

Implementing and communicating the final solution inevitably requires one very important and fragile stage: managing change. Recognize the level of change your solution will require for your customer and predict his reaction to that potential change. Is the customer change averse or change ready? It helps to know how the customer will evaluate your ideas based on how its decision makers think. Do they think and evaluate from an analytical perspective? Do they talk about the process and how it’s going to be implemented? Are they focused on the organization and how it will affect the people in the equation? Or, are they big picture thinkers and readily accepting of new ideas? How they receive and evaluate ideas becomes a filter for how you talk to them.

As with any change management situation, the longer your customer is involved in the solution development, the greater the customer’s buy-in will be. In fact, optimally, you’d want to codevelop the solution with the customer or with key stakeholders in the organization to create shared ownership of the innovation, rather than to unveil something potentially disruptive to the customer and company. As you implement and communicate, consider and manage the important components discussed next.

Understand the degrees of change. For the final solution options, each will have components you can isolate that are significantly different from the current solution. Each different component represents a degree of change. For example, if you’re introducing a new account management program for middle market customers, you may have several degrees of change: introducing a new TeleWeb tech support resource, changing how your resellers interact with the customer, and introducing a new account manager to many of them. Each of these degrees of change represents risk and a communications opportunity.

Develop your positioning. There was a reason you went on this change journey for this particular strategy or customer in the first place. As part of your communication, you need to recapture that reason and position your overall thinking about why you took this approach and, most important, why it will benefit the organization or the customer.

Operate your communications campaign. Borrowing an idea from the advertising business, you need to communicate not in sound bites but in a campaign. Left-brained organizations may find this particularly challenging if they expect that having said it once it need not be said again. We know from observing effective advertising, however, that a great campaign is comprised of target audiences, pointed messages, communications vehicles, proof sources, and message repetition on a schedule. Leverage this successful parallel when building the campaign for your organization or customer.

Manage resistance and push through. In any change initiative, you need to understand the change environment, the potential risks and resistance to change, and your team’s tolerance for pushing through a challenging process to make the change work. As you embark, get a reading on your current situation and know what it will take, where you can be flexible, and how your team can creatively lead through the implementation for a successful outcome.

Bridging Old and New

Maestro Thomas Ludwig is an esteemed composer and conductor, a graduate of the Juilliard School, and the founder of Ludwig Symphony Orchestra and the Beethoven Chamber Orchestra in Atlanta. He has had an illustrious career, including appointments as the music director of the New York City Symphony and resident conductor for American Ballet Theatre with Mikhail Baryshnikov at the Metropolitan Opera House. In the mid-1980s, he conducted the London Symphony Orchestra and recorded with them at Abbey Road Studios (where the Beatles famously recorded and named their 1969 album Abbey Road).

Before Ludwig and the London Symphony Orchestra began recording, Sony contacted him and asked if he would permit the studio to test out a new technology called digital recording. Ludwig agreed to have the experimental equipment placed in the recording studio, and they recorded the session both through the traditional analog technology and the new digital technology. Ludwig says, “When they placed the digital equipment in the studio, despite the fact that it was a totally new innovation, they still had to use the microphones from the analog technology. Of course, these weren’t just any microphones. They were handmade with ribbons wrapped in a special way around the transformers, and cost about $30,000 a piece. We couldn’t record without these microphones because they added warmth to the sound that the digital recording itself wouldn’t have. I found it ironic that this new, cutting-edge digital technology relied on a piece of the old equipment.”

The digital technology was innovative, but it required a bridge from the previous technique—in this case a very expensive microphone. The digital recording equipment wasn’t ready to stand on its own. The same concept applies to new innovations in sales; they don’t always stand on their own; they have to integrate into the existing environment. In some cases they require a bridge, a piece of the old to help transition to the new.

The final step of the Innovative Sale process is to implement and communicate. So, while you may have been developing your vertical solutions in a vacuum of idealism, eventually you have to understand how they’re going to fit with the real world and consider any bridges that may be necessary.

Sometimes the bridge comes in the form of a communication technique. Surprising the customers with a radically new idea will produce a drastically different reaction than telling the customers a story by guiding them through your thought process so they can understand how and why you arrived at this particular solution. You’re liable to meet with rejection in the meeting because the customer won’t have any context for what you’re talking about. For example, in Chapter 3, Jason, the sales rep for the beverage distributor, needed a solution for a customer with a financial concern. The retailer wanted to grow revenue. If Jason had told the retailer, “I know you have a financial concern but we think you really need to focus on food pairings and have some local sports sponsorships,” the customer might have been totally lost. Instead, Jason walked the retailer through his thought process so the ultimate solution made sense.

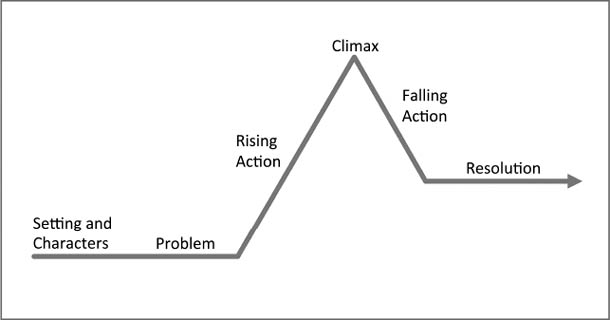

The Innovative Sale story provides a narrative for how you can talk to your customer during this initial communication. We can borrow a parallel from literature and examine how a classic story structure—the statement of the story’s main problem, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution—can structure your Innovative Sale pitch, as illustrated in Figure 6-4 and described in detail as follows.

Setting and characters. Like any good story, begin with your characters (your team and your customer) and the setting (the time and place of the final sales presentation). In the example from Chapter 3, Jason and his team, after generating their new ideas about placing more of their beverages in supermarkets, would meet at the retailer’s store on a Monday afternoon. Jason would explain to the customer what he wanted to achieve in that particular meeting, which was to share some ideas about how Jason can help the customer’s business. Not every story has to begin with the end in mind, but in this case it helps to have a goal. At the end of the meeting, Jason would get the retailer’s feedback about his proposal and discuss how he could further develop it to make sure it would work.

FIGURE 6-4. THE INNOVATIVE SALE STORY.

Problem. What story would be worth hearing if it didn’t have a problem? Talk about the customer’s problem, which, in the case of the retailer, concerned growing revenue. Briefly acknowledge and recall your discussion with the customer about this problem.

Rising action. Rising action is where the plot begins to thicken. Take the customer’s challenge question, interpret it, and redefine it if necessary. Discuss how you might have thought about the challenge question in other ways, specifically the four customer challenge dimensions from Chapter 3. Jason understood they had a financial concern, and he acknowledged it. He might also acknowledge the product concern by examining different segments of the beverage industry. With market concern, Jason could have said, for example, “I know you are a big retailer and you’re trying to connect more with your local community.” Concerning resources, Jason could have said, “We know you have some challenges in terms of expertise and manpower on the floor to be effective at marketing and merchandising.” Showing the customers a range of concerns builds the rising action and prepares them to hear your range of solutions to address all of these challenges, followed by your final solution.

Climax. At the climax of the story, take the concerns most important to the customer and propose your range of solutions. You don’t want to mention your final solution just yet. Instead, give the customer a glimpse of your thought process by discussing the different options. For example, Jason could have shared a conservative approach on the right side of his horizontal idea development: “We’d like to expand our shelf space and do price specials with the waters.” He could also have shared one of the really radical ideas on the left side: “Let’s have a female body builder in the store; shoppers win a year’s supply of water if they can beat her at arm wrestling!” You’ll get a reaction from the customer for each suggestion, but remind him these ideas are not what you’re proposing. You’re displaying your range of consideration. (And, if your customer would react poorly to the suggestion of arm wrestling a female body builder, or anything along those lines, offer a less radical suggestion.) The point is to eventually say, “We’re not recommending that, but we liked a small piece of the idea.” In Jason’s case, the “small piece” was the prospect of outsiders—nutrition experts—assisting with merchandising. Using some outlandish ideas often pushes the customer off-center and creates a few laughs to lighten the conversation. But it has a more important role: preparing the customer to consider an innovative idea. By demonstrating the range of ideas, you’re placing two anchors: one on the conservative end and one on the ridiculous end. Ultimately, this positions your solution somewhere within a reasonable middle where you can finally offer it. You have explained your understanding of the problem and displayed the variance of ideas. Tell the customer why this solution will work best.

Falling action. In falling action, show the customer how your solution works, and prove why it works. If applicable, have a prototype ready. For the beverage retailer, Jason may have presented mockups of the promotions he proposed. He may even have invited a nutritionist along to discuss ideas and share stories from parallel situations. Financial proof is almost always important. Discuss the results your customer will see on a pro forma basis, looking ahead into the future.

Resolution. Finally, in the resolution of the story, talk about how you can take action to move forward.

Through the Innovative Sale story, you’ve brought the customer up to speed in a short period of time. The classic story structure offers a well-proven method of communicating a lot of information in a clear way. And, of course, as with any good story, embellish with details and plot twists as your time and audience allow.

Making It Flow

When I was a kid in upstate New York I took drawing classes at the local art museum every Saturday. We met on the top floor where the skylights faced north, the best position for consistent lighting throughout the day. I sat straddled on a wooden bench with my pad propped up on the drawing board in front of me. At the time I was the youngest person there, the only child in a room of adults; but I held my ground.

It was a life drawing class, so we spent a lot of time drawing portraits, especially faces. During the first class, I drew the face of the model as I always had before: I started with a round shape, put the eyes near the top of the head and the mouth at the bottom, and then filled in the rest. But as the class progressed and I learned how to draw, I realized there were rules of drawing. The human face is generally oval, not round. The eyes are actually almost at the center of the head, and from there the nose and the mouth descend. The tops of the ears align with the eyes, and the bottoms of the ears align with the bottom of the nose. Similar proportions apply to drawing the rest of the body. For example, the width of your arms, fingertip to fingertip, is about equal to your height. I learned many rules and techniques that made my drawing much, much better.

At first it was all very mechanical and awkward. I preferred my method of drawing, which was just trying my best to draw it as I saw it, without any rules or structure. But after a lot of practice, these rules became natural, and I realized that following these and many other principles of drawing made me a much better artist.

The Innovative Sale process works in a similar way. At first, practicing some of these steps may seem awkward, and it may feel easier just to go back to the way you worked before. But after practicing several steps at a time—maybe not the entire process in one shot—and integrating them into your work, you will grow more comfortable and produce results. The process will become natural to you. What looks like individual steps to you right now will seem integrated and familiar, once it becomes a process.

I’ve found something similar in one of my favorite hobbies, golf. Over the years I’ve taken many golf lessons. At first, each one seems to require me to think about one more thing during that very brief period of time that I swing a club. But the truth is I learned to play golf over a period of many years. I started by learning about the grip—either interlocking or overlapping. I learned about the stance and how to position each club within my stance. I learned how to shift my body weight and build tension in my hips. The list goes on and on, and gets even longer when I consider the multitude of situations on the course.

After all those years, I still go back for lessons to get better at one thing: how to swing a club and hit a little white ball. It seems so simple, but I’ve invested time and money in making the mechanical natural. And somehow, every time I tee off, all the years of learned mechanics fade to the back of my mind. My body has absorbed them into muscle memory. I don’t think about the mechanics and the individual lessons. I think about a few of my favorite swing tips and then smoothly drive the ball out into the fairway. (Well, I’m still working on that final part.)

The Innovative Sale is not a one-time event but a way of working, a set of practices and habits that help sales executives and sales teams think differently, challenge assumptions, and develop better answers. Learn the principles of the Innovative Sale. Practice the steps in real situations. Gradually pull them together into a single process. Build your creative muscle memory. As you and your team get good at the Innovative Sale, you’ll find that rather than thinking about mechanics and process, you will refer to a few simple ideas to keep your team’s collective creative muscle memory working smoothly.

The Innovative Sale process can be applied to virtually any sales effectiveness discipline from strategy to tactic, from company program to customer solution. As you think about sales effectiveness disciplines, look at four major tiers of the Revenue Roadmap (in the Appendix): understanding the environment, developing a plan, aligning to the customer, and supporting the objectives of the organization.

Here are several areas where you can apply the Innovative Sale:

![]() Gaining insight into your own strategy and value proposition by understanding your customer

Gaining insight into your own strategy and value proposition by understanding your customer

![]() Honing your sales strategy by improving how you segment and target your customers

Honing your sales strategy by improving how you segment and target your customers

![]() Creating a more effective value proposition that aligns with your customer’s needs and the specific situation

Creating a more effective value proposition that aligns with your customer’s needs and the specific situation

![]() Improving your sales process to better match the customer’s buying process

Improving your sales process to better match the customer’s buying process

![]() Designing your customer experience and touch points

Designing your customer experience and touch points

![]() Coaching your customer and sales team

Coaching your customer and sales team

![]() Motivating your team in new ways

Motivating your team in new ways

In the next three chapters, we’ll take a look at how the Innovative Sale can be applied.

INNOVATIVE SALE ACTIONS

![]() Test your horizontal solutions on the customer challenge dimensions.

Test your horizontal solutions on the customer challenge dimensions.

![]() Get attracted to rejection, which is often an indicator of innovation, and remain persistent.

Get attracted to rejection, which is often an indicator of innovation, and remain persistent.

![]() Understand how your customer thinks and evaluates: analytical perspective, process perspective, people perspective, and big idea perspective.

Understand how your customer thinks and evaluates: analytical perspective, process perspective, people perspective, and big idea perspective.

![]() Bring your customer into your thinking by telling your Innovative Sale story.

Bring your customer into your thinking by telling your Innovative Sale story.

![]() Make the process flow into your creative muscle memory to make it part of how you think.

Make the process flow into your creative muscle memory to make it part of how you think.