Workers’ Compensation

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

• Explain the general nature of workers’ compensation laws.

• Utilize the exclusive remedy rule.

• Recognize those injuries that are related to, arise out of, and are in the course of employment.

• Enumerate those actions of employee misconduct that can result in denial of workers’ compensation benefits.

• Define benefits available under workers’ compensation.

• Compare workers’ compensation laws with the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Family and Medical Leave Act.

• Particularize procedural approaches to workers’ compensation claims administration commonly found in most states.

INTRODUCTION

Workers’ compensation (WC) is a state-mandated system for paying various medical and disability benefits to employees who suffer job-related injuries and illnesses, as well as cash payments to partially replace lost wages. Nearly all employees are covered by WC laws (WCL or WCLs).

Although most workers are covered by WCLs there are some common exclusions, including:

• Domestic workers

• Business owners

• Casual workers who work irregularly or sporadically

• Longshore workers, ship crews, railroad workers, and others covered under federal law

An independent contractor an organization hires to accomplish a task or provide a service is not an employee and therefore not covered by WC.

Generally, state laws require employers to obtain WC insurance or prove they have the financial ability to carry their own risk (that is, to self-insure). Each state has its own distinct system regarding who is allowed to provide WC insurance, which injuries or illnesses are compensable, and the level of benefits.

The fact that every state’s WCLs are distinct puts a burden on you to become familiar with the WCL of every state in which you have employees as well as WC concepts generally. HR professionals and managers—you—play a key role in reducing the human and financial cost of injury, illness, and disability in the workplace. Your role includes:

• Preventing injury. You are the front-line expert who best knows your workplace, the employees, and the demands they face. Therefore, you play a critical role in identifying possible health and safety problems in your workplace.

You are a key link to your organization’s resources that have been set up to handle workplace health and safety issues. While you are not expected to know everything about workplace health and safety issues, you should know when and how to use your internal and external resources, such as the company’s WC insurance carrier.

You are a role model and motivator for employees in your organization. The importance you place on workplace health and safety issues is conveyed to them by your actions as well as your words.

You also play the key role in assuring that your department has required safety and health programs and an Emergency Action Plan. (See Chapter 5, Safety and Health.)

• If injury occurs, initiate required reporting. For example, file first report of injury forms to the company’s WC insurance carrier and notify OSHA, if appropriate. (See Chapter 5.)

• Provide transitional work for temporary disabilities. Disability management efforts are dedicated to reducing the human and fiscal cost of workplace disability to your organization. This is accomplished by:

• Providing education and early intervention services to prevent or minimize the effects of disability in the workplace

• Facilitating early identification, referral, and treatment for disability and/or injuries at work

• Assisting employees with disabilities in overcoming disability-related restrictions or limitations

• Implementing organizational policy and/or contract provisions regarding return to work, reasonable accommodation, and medical separation

• Consulting with management and other staff members regarding workplace disability issues

• Provide reasonable accommodation for permanent disabilities.

• Assure payroll and unemployment compensation benefits are well coordinated.

Employers that do not comply with their state’s WCLs face fines, criminal penalties, and loss of the protection offered by the “exclusive remedy” provisions of the WCLs. (See Exclusive Remedy Doctrine in this chapter.)

Under WC an injured or ill employee can receive medical, disability, rehabilitation, disfigurement, and death benefits regardless of who was at fault for the injury or illness—the employee, the employer, a co-worker, a customer, or some other third party. In exchange for these guaranteed benefits, employees usually do not have the right to sue the employer for unlimited damages.

WC laws create a tradeoff. Workers give up their right to sue for unlimited damages and the employer gives up the trio of defenses and allows workers to recover without proving fault. This compromise is at the heart of almost all WC laws. See Exhibit 6-1 for a discussion of which state’s law applies when employees work in more than one state or work in one state for an employer located in another.

EXCLUSIVE REMEDY DOCTRINE

Generally, under the exclusive remedy doctrine, once an employer’s obligation to provide workers’ compensation benefits is established, an employee (or his or her estate) cannot sue an employer based upon common law claims for damages sustained as a result of an injury or death that arose out of and in the course of employment—even if the damages result from the negligence or recklessness of an employer. This exclusive remedy also applies to situations in which an employee’s injury or death results from the negligence of a co-employee.

|

xhibit 6-1 |

Because employees may work in more than one state for the same employer, or work in one state for an employer located in another, the issue of which state’s WCL applies can be a confusing one. Employees are tempted to “forum shop” and seek to be covered by whichever state law is most generous, or seek recovery under each state’s law. Consequently, a number of states:

• Place statutory limits on the out-of-state reach of their WCL, and/or

• Allow recovery under multiple state WCLs, but require that the amount received from any earlier recovery be deducted from later ones

Many courts today apply the WCL of the state with the most significant relationship to the facts at hand. That relationship is generally either:

1. Where the employment relationship exists

2. Where the employer’s business is “principally localized” or “localized” in the sense that it does significant business there

If an employer fails to provide required coverage, an employee is allowed to either sue for damages that were sustained as a result of the injury or seek benefits provided under the appropriate state WCL. Under the doctrine, fault never enters the picture and the injured or ill employee receives benefits delineated in that state’s WCL.

The objective of the tradeoff is a system that seeks to provide an efficient system for injured workers to receive medical treatment and indemnity payments, with a minimum of delay, disputes, and cost. The administrative process also permits resolution of disputes without the level of uncertainty and significant costs of civil litigation.

Human resource managers are frequently asked to step in and provide immediate assistance when a crisis affects employees in their workplace. This assistance can range from utilizing a previously well-designed Emergency Preparedness Plan to dealing with a “critical incident” that may have a major emotional impact on the entire organization, such as a significant injury to or the death of an employee.

Often critical incidents bring with them a good deal of finger-pointing as the employee in question and others seek to place blame on the organization for the occurrence. This anger brings with it a thirst for retribution in the form of litigation. It is at this point that you must calmly and clearly remind employees of their rights under WC and explain that WC is their exclusive remedy in situations arising out of and occurring within the scope of their employment.

By immediately initiating your organization’s WC protocols—completing and filing first reports of injury—you can actively focus an injured and aggrieved worker on the recovery process instead of seeking a solution outside of the WC system.

Of course, nothing prevents an injured worker from filing a complaint with OSHA regarding the condition that caused their injury or illness. (See Chapter 5.) OSHA can issue citations and levy penalties outside of the WC system.

Erosion of the Exclusive Remedy Doctrine

In recent years workers have tried to attack the exclusive remedy doctrine by turning to the courts in an attempt to supplement their statutory workers’ compensation benefits with tort (civil wrongs) awards. These attacks have met with mixed results.

Some states do allow lawsuits against employers outside of the WC system. Employers can purchase WC insurance that not only includes regular coverage for the vast majority of WC claims but also features an “Employer Liability” (EL) component. EL insurance provides coverage for claims which arise from injuries suffered by employees in the course of their employment that are not otherwise covered by standard WC policy provisions.

And, while most WCLs prohibit injured employees from bringing claims outside of the WC system against co-workers or supervisors, some states do allow at least some suits of this nature.

There are a number of theories employees use in their efforts to sue outside of the WC system, including:

• Dual-capacity doctrine

• Intentional misconduct

• Wrongful discharge and other employment torts

• Disability discrimination

• Bad faith or delay in paying compensation claims

Dual-Capacity Doctrine

In the dual-capacity doctrine, the employer occupies, in addition to its capacity as employer, a second capacity that confers obligations independent of those imposed on it as an employer. For example, an employer may be liable in two ways to an employee who incurs bodily injury on the job as the result of using a product or service produced by that employer: first, as the employer of the injured employee, and second, as the producer of the product or service that caused injury to the employee. The injured employee may then either collect benefits for job-related injuries under WC or sue the employer as the producer of the defective product or service.

Intentional Misconduct

As with other WC issues, the various state courts take different approaches to the argument that the employer’s actions were deliberate and therefore fall outside of the exclusive remedy doctrine.

Some states take the view that intentional misconduct like sexual harassment, assault, and the intentional infliction of emotional distress fall outside of WC coverage, and the employee can sue. Other states force these claims back into the WC system. And, some states allow more generous awards within the WC system for certain employer misconduct.

An employer that intentionally causes harm to its employees will almost certainly not be shielded by insurance if an injured employee is able to sue outside of the WC system. The standard National Council on Compensation Insurance, Inc. (NCCI) policy form, upon which many WC insurance companies’ policies are based, specifically excludes EL coverage for “bodily injury intentionally caused or aggravated by you.” In other words, if an employee’s injury arises as a result of an intentional act which is either:

• Perpetrated by the employer, or

• Perpetrated by an employee at the direction or instigation of the employer then the employee may have a common law right for damages against the employer not covered by WC or EL insurance.

In order to prevail, an employee needs to prove that the employer’s acts were deliberate and intentional, not merely reckless.

Wrongful Discharge and Other Employment Torts

Under virtually every WCL an employer cannot retaliate against the employee for having filed a WC claim. Basically, the employer cannot fire the worker or negatively impact other conditions of employment because the worker filed a WC claim. It can take a negative employment action after a worker has filed a WC claim if the adverse action, including termination, is for legitimate, work-related reasons—such as no work being available when employee is released to return to work.

Separate from WCLs are federal and state employment laws dealing with discrimination, harassment, whistleblowing, family and medical leave, and so forth. (See Chapter 3.) Even if a worker is barred by a WCL from filing a case for injury from sexual harassment or other similar discriminatory or harassing actions outside of the WC system, the employee can file a claim with an appropriate federal agency or court.

Disability Discrimination

The Americans with Disabilities Act, the federal Family and Medical Leave Act, and the federal Rehabilitation Act all provide legal remedies outside the scope of the WCLs.

Bad Faith or Delay in Paying Compensation Claims

A few states (most do not) allow a WC claimant to sue the WC insurer outside of the WC system for failure or delay in paying benefits if there is no reasonable basis for the failure or delay.

Many states have failure and delay penalties build into their WCLs and force claimants to act only within the WCL.

|

Exercise 6-1 |

Instructions: Read the scenarios and answer the questions.

Scenario 1: Ralph is a machinist at the Abrasive Wheel Company. He has received extensive training about locking and tagging out equipment before he undertakes any maintenance or repair of it. A piece of metal becomes lodged in a pneumatically powered machine he is working on. Ralph turns the machine off and contemplates the 20 minutes it will take him to properly take the machine out of service, remove the piece of metal, and return the machine to service. He decides to simply reach in and remove the metal. As he does so, pressure in the line shoots the piece of metal forward, severing one of his fingers. He files a workers’ compensation claim. Abrasive Wheel asks its workers’ compensation insurance carrier to fight Ralph’s claim. It also fires him. Ralph files suit arguing he is entitled to receive benefits and has been retaliated against for filing a workers’ compensation claim.

Question 1: Do you think Ralph will receive WC benefits even though he clearly caused his own injury? If not, why not? If so, why?

Question 2: Do you think Ralph will be able to prove that he was retaliated against for filing a WC claim? If not, why not? If so, why?

Scenario 2: George works at the Abrasive Wheel Company. He is using a grinder fitted with an abrasive wheel manufactured by the company. The wheel disintegrates and a piece flies off and causes deep and serious puncture wounds to both George and Mary, a worker who had been walking by when the wheel came apart. An investigation determines that the wheel was defectively manufactured.

Question: If you were representing both George and Mary, what claims would you make on their behalf?

Solutions:

Scenario 1, Question 1: WC is a no-fault system. Therefore, unless Ralph purposely hurt himself, he is entitled to receive WC benefits.

Scenario 1, Question 2: WCLs only prohibit retaliatory discharge of an employee because he or she filed a WC claim. An employee can be discharged for any other legitimate business reason such as violations of major safety rules, unsatisfactory job performance, or excessive absenteeism. Ralph violated a major safety rule and, therefore, will probably lose his claim of retaliatory discharge.

Scenario 2: Mary is plainly entitled to WC benefits. Abrasive Wheel has a dual relationship with George. It has WC responsibility as his employer, but it also has a duty to exercise reasonable care as the manufacturer of a product. Therefore, in some jurisdictions, if the wheel was defective, then George can receive benefits under workers’ compensation or sue the employer as the manufacturer of the defective wheel.

LOANED OR BORROWED EMPLOYEES

The British common law that is the basis of statutes in 49 states (with Louisiana following the French civil code) contains a principle often referred to as the borrowed-employee doctrine. This principle holds that the employer of a borrowed employee, rather than the employee’s regular employer, is liable for the employee’s actions that occur while the employee is under the control of the temporary employer.

This principle comes into play in the WC world when an employee, Shoichi, on the payroll of Company A is loaned to Company B. If Shoichi is injured while doing work for Company B, which company is responsible for paying the WC benefits? The answer depends on whether or not Shoichi was a loaned/borrowed employee. (“Loaned” and “borrowed” are used interchangeably.)

For Shoichi to qualify as a borrowed employee, Company A, the “general employer,” must loan him to Company B, the “special employer,” for a limited amount of time. In addition, a three-prong test must generally be satisfied:

• The loaned employee (Shoichi) has a contract of hire, express or implied, with the special employer (Company B)

• The work being done is primarily that of the special employer (Company B)

• The special employer has the right to control the details of the work

If Shoichi qualifies as a borrowed employee he loses his common law right to sue the special employer for negligence. In other words, he is now covered by the exclusive remedy doctrine vis-à-vis the special employer. As a general rule, both the general and the special employer are responsible for WC benefits and can claim the protection of the exclusive remedy rule.

Employee Leasing Organizations

The issue of borrowed employees always comes up in the context of employee leasing services (generally known as “professional employer organizations” or PEOs). The employee is on the payroll of the PEO but actually does work for and is directed by the PEO’s client. State laws heavily regulate this area as to which employer must be responsible for WC.

Statutory Employer Laws

More than 40 states have some form of law called either a “contractor-under” or a “statutory employer” statute. Under these laws, general contractors are treated as a “secondary employer” of the employees of subcontractors. If the subcontractor fails to obtain WC coverage, the subcontractor’s employees may obtain compensation benefits from the general contractor.

In states where contractor-under laws exist, general contractors argue that their status as “statutory employers” should allow them to benefit from the exclusive remedy rule and be immune from common law negligence suits by the employees of subcontractors. The success of this argument depends on:

• The specific wording of the particular state’s contractor-under statute

• The interpretation of the statute by the state’s courts

• Whether the subcontractor was uninsured so that the general contractor has to pay compensation benefits

GETTING WC INSURANCE

Various types of WC insurance are available to employers. In a few states coverage is only available through a state fund (“monopolistic fund”).

Generally WC insurance is available through private carriers (except in states with monopolistic funds). And, in many states there are “assigned risk pools” for employers that cannot obtain insurance from private carriers. Also, except for North Dakota and Wyoming, states allow certain employers to self-insure. Self-insuring is also available in most states for groups of employers acting in concert.

WORK RELATEDNESS

Not all employee injuries and illnesses are covered by WC. To be covered injuries and illnesses must:

• Have resulted from an accidental occurrence

• Arise out of employment

• Arise in the course and scope of employment

Accidental Occurrence

Things that constitute “accidental occurrence” sometimes are counterintuitive. For example, if a worker is making a deposit at the bank on behalf of his or her employer and is hurt by a bank robber, the injury is clearly caused by a purposeful act and not something “accidental.” However, the injury was unexpected and unforeseen by the claimant. That would qualify as an accidental occurrence for WC purposes. The key is that the occurrence takes place unexpectedly from the viewpoint of the claimant.

Many states also require that there be some certainty as to when the injury actually occurred for it to be considered accidental. The more definite the time when the injury occurred, the easier it is to identify an event as having been accidental. Many states have stated timeframes within which notification of an injury or illness must be given to the employer.

“Ordinary Diseases of Life”

An occupational disease is any disease which is proven to be due to causes and conditions which are characteristic of a particular occupation or employment and the exposure is greater than that of the general public. Diseases of this type are generally caused by a series of events of similar nature, occurring regularly or at frequent intervals over a period of time in the claimant’s employment.

All states require that there be proof that the claimant’s illness is work-related. This can be difficult to do and often requires input from experts. The same degree of unexpectedness and definitiveness of time aren’t required for occupational illnesses. Many illnesses develop over time. States may impose different requirements for proving an illness than for proving an injury.

Many states exclude from coverage “ordinary diseases of life” to which the general public is equally exposed are excluded. However, since many ordinary diseases of life occur both at home and at work, even states with the “ordinary diseases of life” exclusion will cover work-related illnesses if the claimant has a greater risk of getting the disease at work than the general public.

|

Exercise 6-2 |

Instructions: Check “Yes” or “No” regarding WC coverage of the scenarios posed. and explain your choice.

Solutions:

The most common occupational disease claims involve diseases like asbestosis and silicosis. Also common are claims for occupational hearing loss and musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and repetitive stress injuries (RSIs). Individual facts, state laws, and court decisions will determine work-relatedness of these illnesses.

Psychological injuries are compensable if there is medical evidence that employment was a substantial contributing factor. Several courts have ruled that no compensation is payable for a psychological injury if the injury was wholly or predominantly caused by reasonable action taken or proposed to be taken by or on behalf of the employer with respect to transfer, demotion, promotion, performance appraisal, discipline, retrenchment, or dismissal of workers, or provision of employment benefits to workers.

Since employees work for different employers during their careers and occupational disease is often the result of a long period of exposure, different employers may be responsible for a claimant’s illness.

Many WCLs set rules for assigning liability, including: apportionment of liability among responsible employers, limited apportionment of liability, the last injurious exposure liability, and the last exposure liability (in which the most current employer is totally responsible). If all previous employers and the last employer of a diseased worker are responsible for the exposure, these rules may be condensed into either prorating liability among the employers or the last employer liability.

In many states only the last employer is responsible and may not seek contribution from any previous employer. However, a number of states require a specific level of exposure or a minimum number of days the employee has worked before making the last employer liable.

Pre-Existing Conditions

Most courts have ruled that an employer takes a worker as they find them. Basically, you are totally responsible if you hire an employee who has a back problem and they suffer an incapacitating injury that someone with a normal back would not have suffered. You are not entitled to argue that you should only be responsible for the “difference” between their pre-existing condition and the shape they are in now.

Since the above situation would discourage employers from hiring workers with disabilities, states have created “second injury funds” that help offset the additional expenses of hiring workers with pre-existing conditions. And some states have passed laws excluding pre-existing conditions from WC coverage. Basically these are apportionment statutes.

Multiple Compensable Injuries

Situations where a worker gets hurt at different times while working for the same or different employers are very difficult to deal with. For example, assume an employee suffers a 25 percent loss of function in his or her left arm while working for Employer A. He or she receives a WC award from Company A’s insurer. The same worker goes to work for Employer B and suffers an injury causing 100 percent loss of use of his or her left arm. He or she would now be entitled to receive an award for the total disability, resulting in a more than 100 percent total award, unless this happens in a state with a second injury fund or an apportionment statute.

Because of the complicated nature of multiple injury cases you should check with local lawyers specializing in WC law when dealing with this type of claim.

INJURIES “ARISING OUT OF” EMPLOYMENT

An injured worker is entitled to WC benefits only if the injury arose out of and in the course of employment. The first part of this requirement, “arising out of employment,” ensures that there is a causal connection between the work and the injury.

Usually the employee has the burden of proving that the injury was caused by exposure to an increased risk from employment. There are various approaches that state WCLs and court cases take regarding whether or not a claim arose out of employment: increased risk, personal risk, and neutral risk. A minority of jurisdictions allow a theory of “positional risk.”

Increased risk is risk associated distinctly with the specific type of employment involved. Basically, this approach requires that the risk that causes the injury or illness exceed the risk to the general public. A painter falling from a ladder is an example of “increased risk.” This type of injury is always compensable as arising out of employment.

Personal risk, as the words imply, is risk that is personal to the claimant. An example is a worker who has epilepsy. The employee has a seizure at work, falls down and breaks his or her arm. If nothing in the work environment caused or contributed to the seizure then this was a personal risk, and would not be compensable.

Neutral risk is neither distinct to the employment nor distinctly personal. A roofer hit by lighting is probably covered, but an office worker hit by lightning while leaving work probably is not. The facts of each case will dictate whether the injury or illness arose out of the employment.

Positional risk is where the injury occurred because the employment required the worker to occupy what turned out to be a place of danger. Under this “positional” risk, or “but-for” test, the need to establish a causal relationship between in employment and the injury is relaxed or even eliminated. This theory is only allowed in a few states.

|

Exercise 6-3 |

Instructions: Read the scenarios and select the best answers to the questions.

Scenario 1: Charlene’s Chop House is a restaurant located in an expensive area of town. Abdul-Aziz, Charlene’s bartender, is working near the restaurant’s large glass window and sustains gunshot wounds during a gang shootout. Abdul-Aziz files a WC claim. His employer wants the claim denied, saying that his injuries did not arise out of his employment.

Question: What theory or theories of recovery could Abdul-Aziz use in filing a WC claim?

a. Increased risk

b. Positional risk

c. Neutral risk

d. Personal risk

Scenario 2: Alana’s Chop House is a restaurant located in a high crime area. Jaskirit, Alana’s bartender, often works late at night. Jaskirit has a well-known heart condition. There is a history of gunfire in the neighborhood. Jaskirit is working near the restaurant’s large glass window when gunshots from a gang shootout shatter the window. Jaskirit suffers a heart attack and misses several weeks of work. Jaskirit files a WC claim. His employer wants the claim denied saying that his injury was caused by his pre-existing heart condition and did not arise out of his employment.

Question: What theory or theories of recovery could Jaskirit use in filing a WC claim?

a. Increased risk

b. Positional risk

c. Neutral risk

d. Personal risk

Solutions:

Scenario 1: Given the facts, the best answer is (b). Abdul-Aziz can argue positional risk. That argument will only be viable in a few jurisdictions. He had no greater risk of being hit by gunfire in his job than any other member of the general public in the setting given. There was no increased risk.

Scenario 2: The best answer is (a). Jaskirit can argue that given the environment and history of the neighborhood that he was exposed to an increased risk, and that a situation arising out of his work caused his heart attack—not a noncompensable personal risk.

See: Restaurant Dev Group v. Oh, 2009 Ill. App. LEXIS 407 (June 16, 2009)

INJURIES “IN THE COURSE OF” EMPLOYMENT

In addition to the requirement that an injury arise out of employment, the claimant must show that the injury arose “in the course of employment.” To arise in the course of employment, the injury must take place within the employment period, in a location where it is reasonable for the employee to be, and while the employee is fulfilling work duties. The employee doesn’t actually have to be performing his or her job, but must be acting within the scope of the employment.

“In the Course of” Legal Doctrines

Just as with “arising out of” cases, WCLs and court decisions consider a number of legal doctrines in determining whether an injury or illnesses occurred within the course and scope of employment.

Personal Comfort

This doctrine covers injuries that occur on the employer’s premises while the acts such as eating, drinking, smoking, seeking relief from discomfort (getting warm, getting fresh air or relief from heat, seeking toilet facilities), preparing to begin or quit work, and resting or sleeping. Courts generally take an expansive view of what constitutes the employer’s premises, with parking lots being included.

Injuries occurring on the premises during personal comfort activities, including during meal and break periods, are generally covered. Off-premise personal activities are generally not covered unless work-related (for example, lunch with a client).

In general, the following rules apply to WC coverage for business-related travel:

• To and from work–Employees are generally not covered by WC while commuting to and from their employer’s premises. Exceptions to this rule, depending on the circumstances, are:

• When the employee is running an errand for the employer

• When the employee is operating a company-owned vehicle

• When the employee was required to do something at home or elsewhere before coming to the employer’s premises

• Route deviations – If an employee deviates from a business trip route for a personal reason, he or she will not be covered by WC until he or she returns to the business trip route. However, if the deviation is basically inconsequential (including personal comfort activities like eating or seeking out a rest room) the employee may still recover benefits if injured on the minor detour.

The question of compensability and the analysis of the facts focus on where the employee was injured. In other words, just because the employee intended to take a detour to visit a casino, if he or she was injured before reaching the point of departure from the business route, the injuries would be covered by workers’ compensation.

Not all jurisdictions require the employee to regain the business trip route for workers’ compensation protection. Some states merely require the employee to have completed the personal nature of the detour and be moving toward the business trip destination

• Travel involving dual purposes–Dual-purpose travel occurs when the employee embarks on a trip on behalf of the employer that coincides with travel for the employee’s benefit. In other words, the journey serves both the business purpose of the employer and the personal purpose of the employee (as when an employee drops off a business package on the way home).

If the worker is injured during the business portion of the trip WC would apply. Basically, WC applies if the employee would have had to make the trip even if there weren’t a personal component to it.

Telecommuting

If someone’s home is a second worksite, then WC applies to their injuries sustained in that worksite as long as they were acting within the scope of their employment. The claimant must show that the injury arose out of and was in the course of his or her employment.

Horseplay

States vary in how they treat WC claims for injuries received during joking or prankish behavior at work. Generally, however, horseplay is considered a gross departure from work activity and is not covered.

Courts will look at three factors in determining if horseplay injuries are covered:

1. Did the injured worker instigate the horseplay?

2. Had the employer tolerated horseplay in the past?

3. Was the horseplay so extreme as to not be foreseeable?

Fighting

Injuries from workplace fights will be covered if the cause was work-related. If, however, the fight stems from non-work-related reasons (a fight over a boy-or girlfriend, for example), WC would not apply. Some states will allow recovery only for the worker who did not start the fight.

Assaults by third parties generally are covered if the work increases this type of risk.

Recreational and Social Activities

If an employee is injured while participating in an employer-sponsored recreational or social activity a key consideration regarding WC coverage is: was the worker’s participation voluntary? The more mandatory participation was, the more likely it is that WC will apply.

EMPLOYEE MISCONDUCT

Injuries received while engaged in misconduct may not be compensable under WCLs. Exact laws, of course, vary from state to state. However, four categories of misconduct usually result in denial of coverage, namely:

• Willful misconduct. This is misconduct that involves activities that have no legitimate tie to the workplace.

• Violations of safety rules. Because WC ignores an employee’s negligence, for an employer to prevail on this defense it must show that:

• The rule was actual company policy

• The policy was strictly enforced

• The claimant’s failure wasn’t merely carelessness or accidental

• Intoxication/illegal drug use. Generally, the employer has the burden of proving that the intoxication or illegal drug use played a role in the injury. In states that have created a presumption that intoxication or illegal drug use caused the injury, the burden of disproving it falls on the claimant. Some states reduce the amount of the WC award based on the role intoxication or illegal drug use played in the injury.

• Misrepresentation of physical conditions. In many states WC benefits will be denied if:

• an applicant has intentionally misrepresented his or her medical condition, and

• the previous injury causes the worker to suffer another injury.

Caution: The Americans with Disabilities Act does not permit you to ask medical questions prior to making the applicant a job offer conditioned on his or her passing a medical exam that tests the person’s ability to perform the essential functions of the job in question. (See Chapter 1.)

|

Exercise 6-4 |

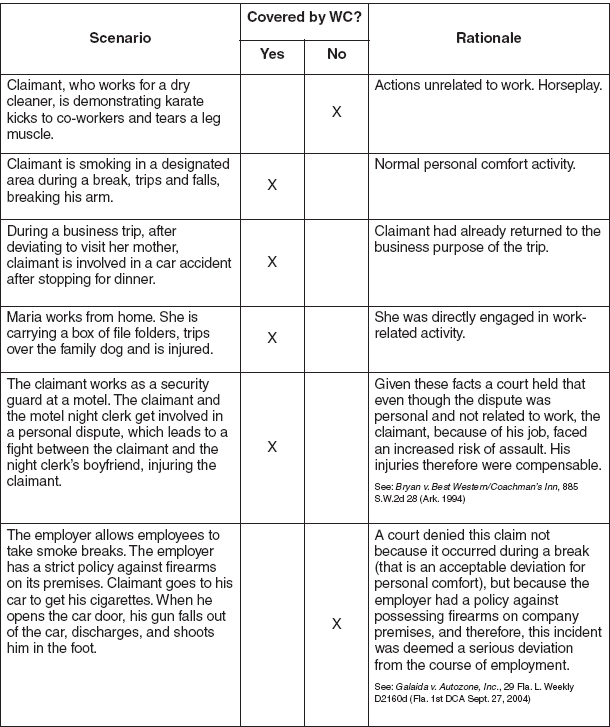

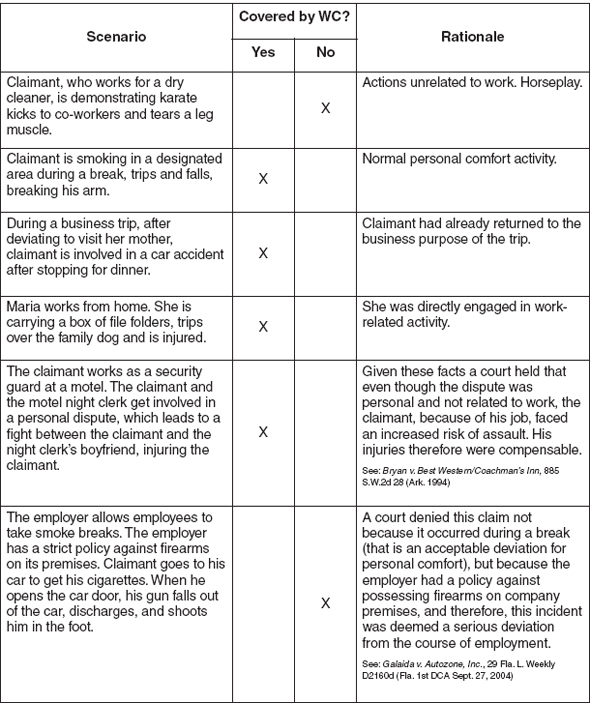

Instructions: Indicate whether you believe the following scenarios are covered by WC and explain your response.

Although each state has its own unique WCL, all states provide:

• Disability benefits for injured workers. This compensation is for physical impairment or lost wages. Disability benefits for lost wages are variously called “income” benefits, “wage-loss” benefits, or “time-loss” benefits.

• Medical benefits to injured workers. These benefits cover medical care and help the worker recover physically. A number of WCLs also include vocational rehabilitation, disfigurement, and death benefits.

Disability Benefits

Benefits for disability vary by duration (temporary or permanent) and severity (total or partial).

Sometimes a worker will be injured, but will not miss any work time or very little and will be able continue working. In these cases no WC benefits will be paid. In most states there are several types of disability benefits that are compensable:

• Temporary total disability. This is the period of time following an accidental injury when an employee is totally incapacitated and cannot work. The claimant eventually fully recovers and returns to full-time employment.

• Temporary partial disability. These benefits are intended to replace lost income for workers who, although able to return to work, are unable by reason of the injury to earn the same wages as before the injury. Examples are the employee who returns to work on a part-time basis and the worker who returns to work at a lower wage rate.

• Permanent partial disability. Permanent partial disability is generally defined as any anatomical abnormality after maximum medical improvement has been achieved, which abnormality or loss the physician considers to be capable of being evaluated at the time the rating is made. A worker’s medical condition is considered to have reached maximum medical improvement when no further material improvement would reasonably be expected from medical treatment or the passage of time.

• Permanent total disability. The various definitions of permanent total disability often describe two separate conditions which constitute permanent total disability.

• The first condition is “economic disability.” Permanent total disability from an economic standpoint is not synonymous with total incapacity or total dependence, but means a lack of ability to follow continuously some substantially gainful occupation without serious discomfort or pain and without material injury to health or danger to life.

• The second condition is what is referred to as “statutory permanent total disability.” The loss of both hands, both feet, both legs, both eyes, or any two thereof creates a presumption of permanent total disability, regardless of the earning capacity of the employee.

Every state imposes a waiting period after an injury before disability benefits are payable. If the duration of the disability goes beyond a specified period of time, then the benefits will be paid retroactively from the date of the injury. For example, the waiting period for benefits to begin might be seven days, but if the disability extends beyond 14 days compensation will be available from the date of the injury.

Benefit Wage Calculations

Benefits are generally based on a percentage of the injured worker’s gross wages. The most common percentage is 66 ![]() percent.

percent.

Virtually all states have both minimum and maximum benefit limits. Maximums and minimums are generally based on the statewide average weekly wage.

THE BERMUDA TRIANGLE – ADA, WC, AND FMLA

One of the most frustrating situations a human resources manager must deal with is an employee who is out on leave for a workers’ compensation injury and either requests an indefinite leave or stays out on leave indefinitely. All too often the HR manager will not take any meaningful action to rectify the situation out of fear of a claim of retaliatory discharge under state WC laws, or claims of discrimination under the ADA or interference with rights under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA). The difficulties in administering these three laws vis-à-vis an employee is often known as the “Bermuda Triangle.”

To do nothing is to invite absenteeism, employees on indefinite leave, employees who will not provide requested medical information supporting the leave, or employees who will not provide a projected date on which they intend to return to work. Contributing to the employer or human resources manager’s uncertainty is the fact that the ADA, the FMLA, and WCLs appear to work in unison to protect the employee from any adverse employment action related to the leave.

In seeking to remedy the problems mentioned it’s important to understand that these laws are not intended to accomplish the same goals.

• The chief purpose of WCLs is to compensate injured workers while insulating employers from litigation.

• The chief purpose of the employment provisions (Title I) of the ADA is to eliminate discrimination against qualified individuals with disabilities who could perform the essential functions of the job, with or without reasonable accommodation. (See Chapter 1.)

• The chief purpose of FMLA is to allow employees to be absent from work for certain family and medical reasons, without penalty. (See Chapter 7.)

The conflicting nature of these goals causes confusion when an injured worker cannot perform all of the tasks of a job and the employer wants to either get him or her back to work as quickly as possible or fire the worker, but is prevented from doing either by the FMLA, which does not let the employer force the worker to come back until after the employee’s FMLA rights are exhausted, and the ADA, which forces the employer to accommodate the employee’s disability by actually changing the job unless doing so would be an undue burden.

You must also understand who these laws cover and the specific benefits they offer in different situations. Whichever law provides the worker with the greatest benefits in a given situation is the law you follow. You must absolutely undertake an individual, fact-specific analysis in order to come to the right conclusion. See Web Exhibit 6-1 at www.amaselfstudy.org/go/HRPractice for a comparison of the main features of these laws.

ADMINISTERING WC CLAIMS

Considerable variation exists in how claims are administered in each of the states. However, some commonalities are:

• The vast majority of states use a specialized WC agency or bureau. Some are very active in claims administration, while others are passive.

• All states have judicial review mechanisms to correct errors in original decisions.

Notice of Injury

In most states the claimant must first give a notice of injury to the employer within a specified number of days (set out in the state’s WCL). If the employer has actual notice of the work-related injury, that is enough. No further notice of injury on the part of the employee is required.

A number of states have special first notice requirement related to occupational diseases.

Notice of Claim

All states require that the employee file a notice of claim with the appropriate agency. The deadline for filing varies by state. One to two years is typical. The timeframe for filing an injury claim begins to run on the date of the injury.

The timeframe for filing an occupational disease claim begins to run from the date of discovery. Most states consider the date of discovery to be when:

• The disease first appears

• The employee should reasonably know its relationship to employment

Employers must report work-related injuries to a state agency, bureau, or to their insurance carrier, who will then send the notice to the state agency.

Claim Resolution

Most WC claims are settled without litigation. If litigation does occur, in most states, the first litigation forum is an administrative agency. A specialized officer hears the case. If the parties do not agree on the findings and conclusions of the hearing officer, the next forum is a workers’ compensation board or other tribunal. An aggrieved party can eventually petition a court for judicial review.

In this chapter you have learned that workers’ compensation law is governed by statutes in every state. Specific laws vary with each jurisdiction, but key features are consistent.

The negligence and fault of either the employer or the employee usually are immaterial. A worker whose injury is covered by the workers’ compensation statute loses the common-law right to sue the employer for that injury, but injured workers may still sue third parties whose negligence contributed to the work injury.

Almost every worker is covered by workers’ compensation laws (WCLs), with exceptions being farm workers, domestic workers, business owners, casual workers who work irregularly or sporadically, and those covered by specific federal laws such as longshore workers, ship crews, and railroad workers.

Workers’ compensation statutes require most employers to purchase private or state-funded insurance, or to self-insure, to make certain that injured workers receive proper benefits.

An employee is automatically entitled to receive certain benefits when he or she suffers an occupational disease or accidental personal injury arising out of and in the course of his or her employment.

WC benefits may include cash or wage-loss benefits, medical and career rehabilitation benefits, and in the case of accidental death of an employee, benefits to dependents.

Workers’ compensation laws and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) often overlap with the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), as do state family and medical leave laws. Generally, when more than one employment law applies, the employee is entitled to every benefit available under every applicable law. In other words, you may not focus solely on one law or another. Instead, you must give the employee the benefit of whichever law is

|

Review Questions |

1. An employer complies with most workers’ compensation laws by:

(a) filing an OSHA Form 300 with the state workers’ compensation commission.

(b) purchasing workers’ compensation insurance or becoming self-insured with the appropriate state agency’s approval.

(c) filing an EEO-1 Form with the state workers’ compensation commission.

(d) filing a notice of workers’ compensation petition with both the Secretary of State and the state workers’ compensation commission.

1. (b)

2. ______________is risk associated distinctly with the specific type of employment involved.

(a) Positional

(b) Personal

(c) Increased

(d) Neutral

2. (c)

3. All states require that a workers’ compensation claimant file a ____________ with the appropriate agency.

(a) notice of claim

(b) first notice of injury

(c) affidavit of authenticity

(d) notice of contest

3. (a)

4. Benefits are generally based on a percentage of the injured worker’s gross wages. The most common amount is ________ percent.

(a) 66

(b) 33 ½

(c) 75

(d) 66 ![]()

4. (d)

5. In a borrowed employee situation the loaning employer is known as the_______employer.

(a) special

(b) de facto

(c) de jure

5. (d)