In Space

Space is an illusion in photography. The appearance of space in a two-dimensional image forms a part of the visual meaning in how a viewer reads an image.

The eye and brain have three ways of perceiving depth. The first is the binocularity of two-eyed vision. Each eye holds a slightly different perspective on a subject. The brain interprets these dual perspectives to allow us to recognize space between objects, between us and an object, and the relative location of objects in space. Binocularity operates only at distances approximately 15–20 feet away from your eyes, about the distance in basketball from the free throw line to the basket. All other forms of depth perception are monocular—one eyed—and similar to a camera lens.

The second form of depth perception is motion. If you are in a moving car, for example, the bushes in the foreground appear to be clipping past faster than the mountains in the background. If you are walking, relative motion appears to be more pronounced in subjects closer to you than far away. The third way of seeing and rendering space is perspective. The objects closest to us appear larger than the objects some distance away. If you are drawing a fence, for example, you can use standard three-point perspective, in which the closest fence post is rendered larger, and as the fence posts recede in space, they are rendered progressively smaller leading to the vanishing point.

Since camera vision is monocular, the principal means for alluding to space is through the rendering of perspective and lens choice. Anyone who has studied photography knows the basics. Long lenses (telephoto) compress and flatten space while short lenses (wide angle) serve to open space and render greater depth. What is called a normal lens, approximately 50 mm for a 35mm film camera or a full-frame sensor, offers a spatial perspective that approximates human vision.

Photographers might choose a long lens to zoom in on a subject, as in wildlife or sports, or step back from a subject for a wider view, as in landscapes and urban scenes. However, often photographers choose lenses based on their evocation of spatial relationships. The longer the lens, the more space is compressed; the wider the lens, the more space is opened and apparent depth is increased. This has far-reaching consequences in visual expression. Do we want to enhance or subvert the physical vision of the eye and brain?

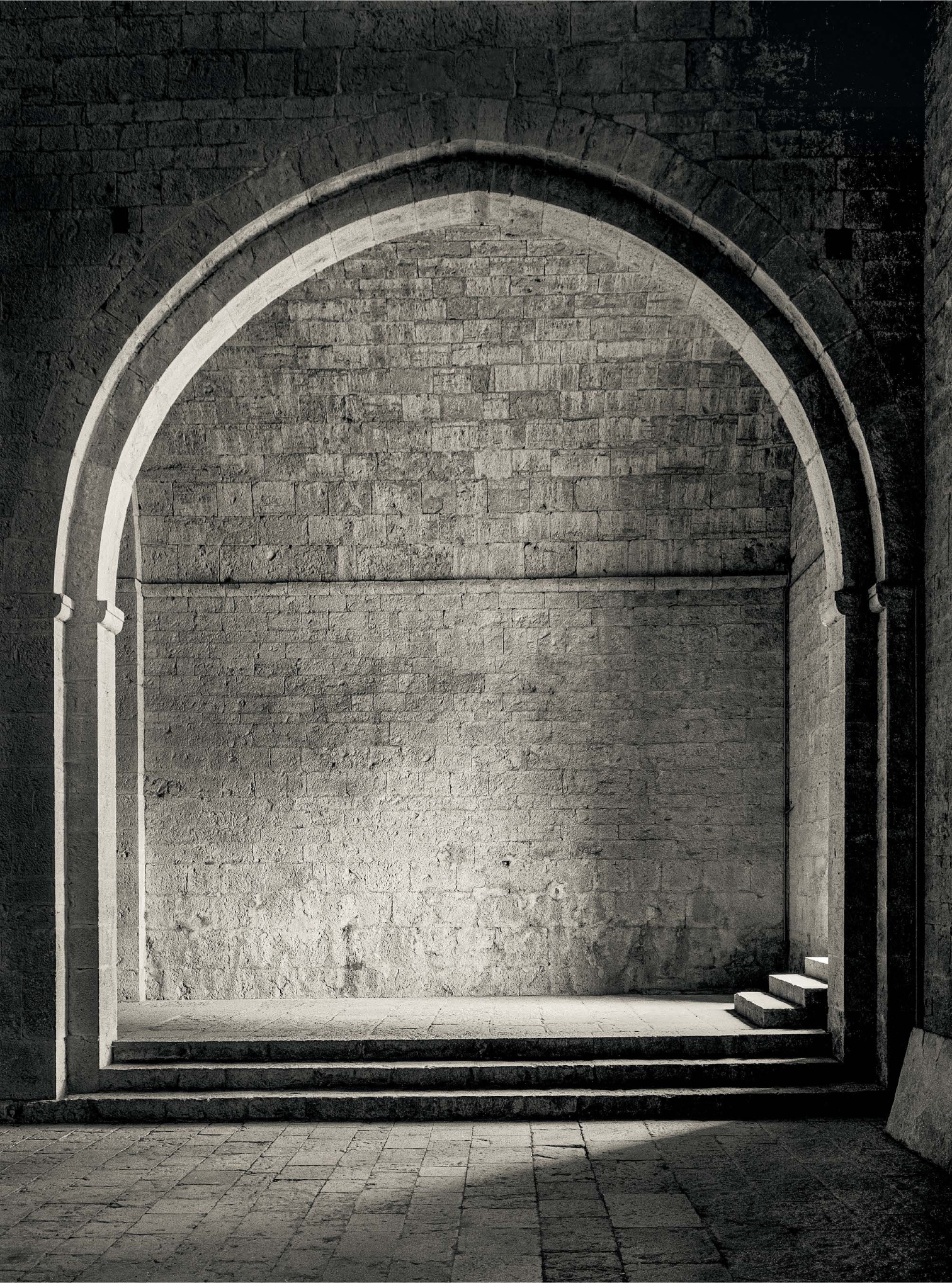

Entrance to the South Aisle, le Thoronet Abbey, 1986, from The Architecture of Silence, David Heald

Compressing space flattens the subject. Cubist and abstract paintings, for example, show the planes of the subject concurrently and not extending into space. Medium-long lenses (70-85mm) flatter human subjects by offering a perspective of the human face without distortion of features. Wide-angle lenses, on the other hand, distort features. What is closer to a camera, like noses, appear larger, and what is farther from the camera, like ears, appear disproportionally smaller. Cell phone cameras have wider lenses, and photos at arm’s length give a sense of comic relief due to distorted noses and lips and smaller heads than what we normally see. Thus, the popularity of selfie sticks, which keep you a greater distance from the camera lens and create less distortion.

Often, beginning photographers seem more comfortable with longer lenses while fine art or documentary photographers often lean toward slightly to moderately wide lenses. It’s easier to organize space and form with longer lenses. You can highlight a single subject with less stray material in the frame to integrate. It’s harder to photograph with wide lenses; more material is contained within the fabric of the frame that needs to be integrated into your visual document.

What meaning are you trying to convey in your photographs? Are you looking at something, as you might do with a long lens, or into something, as you might do with a wide lens? Do you want to evoke depth and space, or work with flat planes of color and form?

Many cameras, including cell phones, have limited lens choices. In these instances, photographers need to employ other tactics beyond the lens to represent space. For instance, try to experiment with near/far relationships, or what we call figure/ground. Place or find an object in the near foreground, closer to your camera, and observe how space opens up as the object interacts with the background. Then, try photographing a scene with nothing in the foreground and observe how the space seems condensed.

Also, when seeing the world through a camera, become aware of negative space, or the space that surrounds and defines objects. The atmosphere itself can evoke spaciousness or constriction, lightness or heaviness. We breathe freely in viewing certain scenes or images, and breath becomes tight and constricted when viewing others. As a photographer, concentrated emotional states or even the expression of anger and fear can often be evoked through the flatness of space, where objects collide and ricochet off each other within the frame.

A friend and fellow photographer, Franco Salmoiraghi, has defined the term, “photographs of nothing,” which refer to images made without any definable focal point in which the space and light and the atmosphere of negative space become the central subject. In these images, the space and the air itself richly vibrate with substance and livingness. As an exercise, try to make images in which the negative space becomes dominant or equal to the definition of the subject, or when the atmosphere itself is rendered with living light.

Can you photograph the air we breathe? For example, writer Barry Lopez believes that, in many photographs by Robert Adams, he displays “An obvious passion for light in his prints, the light streaming down at times like a shower, an effulgence in the air.” He is able to evoke in a photograph the light and atmosphere itself, “making it visible like a plein-air painter.”

And finally, what about the poetics of inner space? Images and art made with capacious perception—mindful seeing—can evoke a broad inner spaciousness, such as the flat canvases of resonating, resounding color by Mark Rothko or the evocative photographs of David Heald of Cistercian Abbeys in France from his book, The Architecture of Silence. In mindful seeing, we strive to locate part of our attention in our body, to become aware of the spaces within and seek to find correspondence in the things we photograph. Images made with sensitive awareness can bring that focused attention invisibly forward into the image. We feel a sense of resounding presence and spaciousness in the neural pathways within the body.