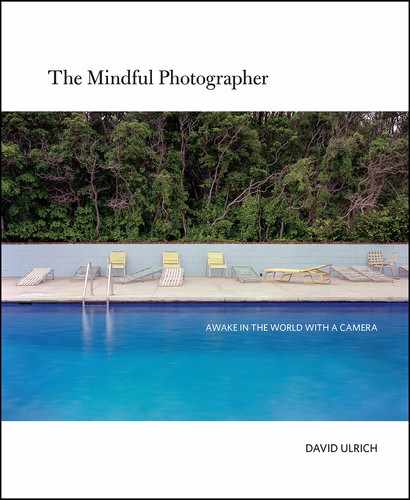

Creative Mind and Not Knowing

Waikiki, 2015, James Knudsen

Photographers often spend a disproportionate amount of energy thinking about and even obsessing over tools and equipment. Does it help? Maybe just a little. Having the right camera or the ideal lens can help make successful photographs. However, this is a limiting and partial attitude. I believe that the pivotal concern that should greatly supersede the quest for more stuff is finding the right frame of mind and cultivating the necessary skills to help us see and work.

What is the ideal working state of mind and how might we achieve it? Artists and photographers have long sought the magic elixir within which creativity can sprout and bloom. To the extreme, some have tried drugs and various kinds of indulgence or privation: alcohol, lack of sleep, celibacy or promiscuity, and fasting. Others don’t think about it at all and come as they are into the field or studio. Certain enduring factors for a working state of mind have emerged from the experiments of creative individuals that are time-tested and reliable.

The first is the advent of a quiet, receptive mind. Stillness of mind does not just appear on its own; we must aim in its direction. Attentive seeing and focused creativity cannot take place in the carnival of the mundane. Reduce distractions, try to clear your mind of shopping lists and daily ephemera and learn to find disciplined focus. Sometimes I work before the daily intrusions begin to dominate; at other times, I take care of urgent tasks before getting to work on a creative project. The one thing that helps me the most comes through the inward attention cultivated in sitting meditation. Buddhists know this state as mindfulness or vipassana.

In the mindful state, we strive to merely accept what is. We cultivate what some call the impartial witness or what Krishnamurti calls “choiceless awareness.” It’s the part of the mind that is large and broad, that is capable of embracing thought and emotions with detached interest. In mindfulness, we do not seek to change things. We strive to see and know what is. Ironically, once the light of awareness is let into the dark places, change does begin to come about naturally. Certain processes in the psyche can take place only in the dark, hidden recesses, apart from conscious awareness. In mindfulness, we observe the mind itself and bear witness to the often raging and ranging thoughts, as well as become aware of reactive emotion. Ironically, this action of becoming aware of thought and emotion has a calming and quieting influence. The rapidly thinking, associative mind does not go away but it occupies less space in our inner landscape, freeing more attention to devote to finding creative focus.

I have verified this repeatedly. I tend toward a hyperactive disposition of both mind and body—and am easily distracted by shiny devices, news feeds, and inner conditions. I feel pulled here and there constantly and, like a child, cannot effectively discipline my peripatetic nature. So where does that leave me? Punishing my body and mind into submission feels demeaning and rarely helps. For me, inward attention, being aware of the direct experience of the here and now, coupled with self-observation or the cultivation of the mind’s witness, acts much like tightening and tuning a guitar string. My anxiety lowers, my body and mind more fully enter the present moment, and a certain creative sensitivity becomes evident in my inner state. I am more responsive, focused, and steadily energetic in my creative work.

The mind quiets of its own accord through mindful awareness. Rather than the fractured mind that is drawn here and there, my mind and seeing become sharper-edged tools for creative application. My mind also opens to new possibilities, new directions, and intuitive guidance from its deeper regions. I enter the flow state, in which endorphins are released, the work gathers its own momentum, and the interaction with tools, materials, and ideas stimulates discovery and leads toward clarity.

One of the hallmarks of a clear, receptive mind is found in the paradoxical Zen concepts of “no-mind” and “not knowing.” In the state of not knowing, we strive to suspend our fixed opinions, immediate judgments, and preconceptions. We maintain a healthy curiosity and attentive interest to the ever-changing here and now. New, creative discoveries cannot be made in a mind overfilled with opinions and speculations. Instead, the mind can be open and can cultivate an enthusiastic, child-like wonder. The mind inquires rather than thinking it knows. Active questioning forms the ideal creative working state. From this standpoint, we can make new discoveries, have a fresh, untainted view of the world, and use the camera for one of its most righteous aims: to learn to see what is.

The mindfulness of no mind encourages a spontaneous, instinctive, and intuitive way of working. We learn to depend upon the wisdom of the body, the subtle ways of knowing of the emotions, and the intelligence of instinct—rather than relying strictly on the rational, plodding disposition of the head brain. Try to look and see without thought. It is hard to stay open and rigorously suspend preconceptions—to let the mind become a blank slate. Try to approach the world with the question: what will I learn today? Try to work with the camera or post processing in a state of inquiry and free, even wild, experimentation. Try to be still and mindful. Allow the moment to unfold without your opinions of how something should happen. Dance with the world, and don’t always try to lead. Intuition prevails when we learn to stop thinking so hard and knowing so much.

Be quiet.

Untitled, from the series Laws of Silence,

Jennifer McClure