8. Frameworks and Reuse: Designing with Interfaces and Abstract Classes

Chapter 7, “Mastering Inheritance and Composition,” explains how inheritance and composition play major roles in the design of object-oriented (OO) systems. This chapter expands upon the concepts of interfaces, protocols, and abstract classes.

Interfaces, protocols, and abstract classes are powerful mechanisms for code reuse, providing the foundation for a concept I call contracts. This chapter covers the topics of code reuse, frameworks, contracts, interfaces, protocols, and abstract classes (for the remainder of the chapter, unless otherwise indicated, I use the term interface to include the concept of protocols). At the end of the chapter, we’ll work through an example of how all these concepts can be applied to a real-world situation.

Code: To Reuse or Not to Reuse?

Programmers have been dealing with the issue of code reuse ever since writing their first line of code. Many software development paradigms stress code reuse as a major part of the process. Since the dawn of computer software, the concept of reusing code has been reinvented several times. The OO paradigm is no different. One of the major advantages touted by OO proponents is that if you write code properly the first time, you can reuse it to your heart’s content.

This is true only to a certain degree. As with all design approaches, the utility and the reusability of code depend on how well it was designed and implemented. OO design does not hold the patent on code reuse. There is nothing stopping anyone from writing very robust and reusable code in a non-OO language. Certainly, countless numbers of routines and functions, written in structured languages such as COBOL, C, and traditional VB, are of high quality and are quite reusable.

Thus, it is clear that following the OO paradigm is not the only way to develop reusable code. However, the OO approach does provide several mechanisms for facilitating the development of reusable code. One way to create reusable code is to create frameworks. In this chapter, we focus on using interfaces and abstract classes to create frameworks and encourage reusable code.

What Is a Framework?

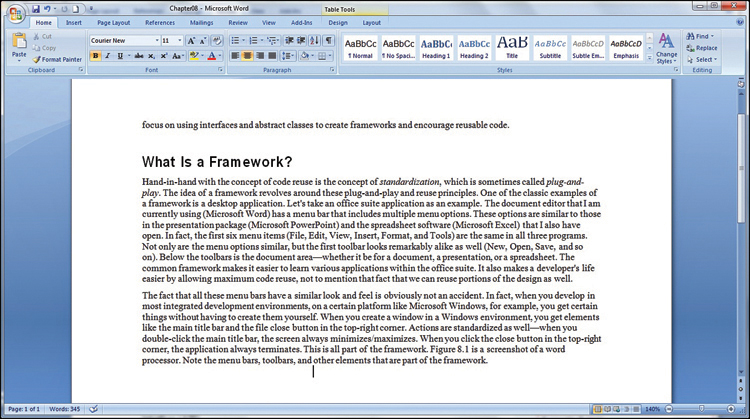

Hand in hand with the concept of code reuse is the concept of standardization, which is sometimes called plug and play. The idea of a framework revolves around these plug-and-play and reuse principles. One classic example of a framework is a desktop application. Let’s take an office suite application as an example. The document editor that I am currently using has a ribbon that includes multiple tab options. These options are similar to those in the presentation package and the spreadsheet software that I also have open. In fact, the first two menu items (Home, Insert) are the same in all three programs. Not only are the menu options similar, but many of the options look remarkably alike as well (New, Open, Save, and so on). Below the ribbon is the document area—whether it be for a document, a presentation, or a spreadsheet. The common framework makes it easier to learn various applications within the office suite. It also makes a developer’s life easier by allowing maximum code reuse, not to mention that we can reuse portions of the design as well.

The fact that all these menu bars have a similar look and feel is obviously not an accident. In fact, when you develop in most integrated development environments, on a certain platform like Microsoft Windows or Linux, for example, you get certain things without having to create them yourself. When you create a window in a Windows environment, you get elements like the main title bar and the file Close button in the top-right corner. Actions are standardized as well—when you double-click the main title bar, the screen always minimizes/maximizes. When you click the Close button in the top-right corner, the application always terminates. This is all part of the framework. Figure 8.1 is a screenshot of a word processor. Note the menu bars, toolbars, and other elements that are part of the framework.

A word processing framework generally includes operations such as creating documents, opening documents, saving documents, cutting text, copying text, pasting text, searching through documents, and so on. To use this framework, a developer must use a predetermined interface to create an application. This predetermined interface conforms to the standard framework, which has two obvious advantages. First, as we have already seen, the look and feel are consistent, and the end users do not have to learn a new framework. Second, a developer can take advantage of code that has already been written and tested (and this testing issue is a huge advantage). Why write code to create a brand new Open dialog when one already exists and has been thoroughly tested? In a business setting, when time is critical, people do not want to have to learn new things unless it is absolutely necessary.

Code Reuse Revisited

In Chapter 7, we talked about code reuse as it pertains to inheritance—basically one class inheriting from another class. This chapter is about frameworks and reusing whole or partial systems.

The obvious question is this: If you need a dialog box, how do you use the dialog box provided by the framework? The answer is simple: Follow the rules that the framework provides. And where might you find these rules? The rules for the framework are found in the documentation. The person or persons who wrote the class, classes, or class libraries should have provided documentation on how to use the public interfaces of the class, classes, or class libraries (at least we hope). In many cases, this takes the form of the application-programming interface (API).

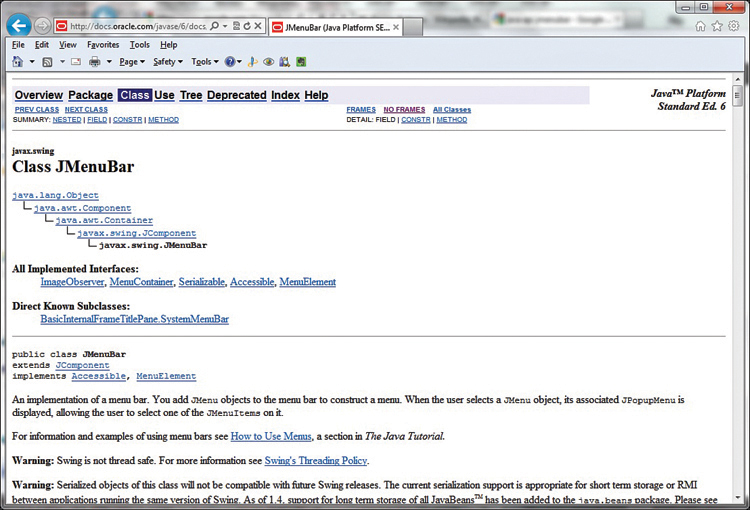

For example, to create a menu bar in Java, you would bring up the API documentation for the JMenuBar class and take a look at the public interfaces it presents. Figure 8.2 shows a part of the Java API. By using these APIs, you can create a valid Java application and conform to required standards. If you follow these standards, your application will be set to run in Java-enabled browsers.

What Is a Contract?

In the context of this chapter, we will consider a contract to be any mechanism that requires a developer to comply with the specifications of an API. Often, an API is referred to as a framework. The online dictionary, Merriam-Webster (https://www.merriam-webster.com), defines a contract as a “binding agreement between two or more persons or parties, especially: one legally enforceable.”

This is exactly what happens when a developer uses an API—with the project manager, business owner, or industry standard providing the enforcement. When using contracts, the developer is required to comply with the rules defined in the framework. This includes issues such as method names, number of parameters, and so on (signatures, and the like). In short, standards are created to facilitate good development practices.

The Term Contract

The term contract is widely used in many aspects of business, including software development. Do not confuse the concept presented here with other possible software design concepts called contracts.

Enforcement is vital because it is always possible for a developer to break a contract. Without enforcement, a rogue developer could decide to reinvent the wheel and write her own code rather than use the specification provided by the framework. There is little benefit to a standard if people routinely disregard or circumvent it. In Java and the .NET languages, the two ways to implement contracts are to use abstract classes and interfaces.

Abstract Classes

One way a contract is implemented is via an abstract class. An abstract class is a class that contains one or more methods that do not have any implementation provided. Suppose that you have an abstract class called Shape. It is abstract because you cannot instantiate it. If you ask someone to draw a shape, the first thing the person will most likely ask you is, “What kind of shape?” Thus, the concept of a shape is abstract. However, if someone asks you to draw a circle, this does not pose quite the same problem, because a circle is a concrete concept. You know what a circle looks like. You also know how to draw other shapes, such as rectangles.

How does this apply to a contract? Let’s assume that we want to create an application to draw shapes. Our goal is to draw every kind of shape represented in our current design, as well as ones that might be added later. There are two conditions we must adhere to.

First, we want all shapes to use the same syntax to draw themselves. For example, we want every shape implemented in our system to contain a method called draw(). Thus, seasoned developers implicitly know that to draw a shape, you invoke the draw() method, regardless of what the shape happens to be. Theoretically, this reduces the amount of time spent fumbling through manuals, and it cuts down on syntax errors.

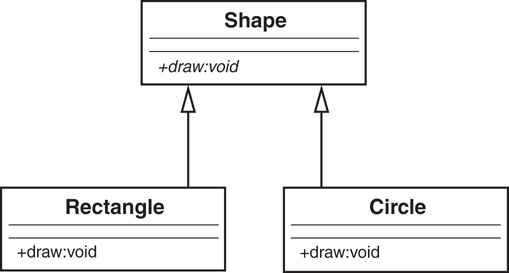

Second, remember that it is important that every class be responsible for its own actions. Thus, even though a class is required to provide a method called draw(), that class must provide its own implementation of the code. For example, the classes Circle and Rectangle both have a draw() method; however, the Circle class obviously has code to draw a circle, and as expected, the Rectangle class has code to draw a rectangle. When we ultimately create classes called Circle and Rectangle, which are subclasses of Shape, these classes must implement their own version of draw() (see Figure 8.3).

Abstract Methods

In the UML diagrams, note that the abstract methods are italicized.

In this way, we have a Shape framework that is truly polymorphic. The draw() method can be invoked for every single shape in the system, and invoking each shape produces a different result. Invoking the draw() method on a Circle object draws a circle, and invoking the draw() method on a Rectangle object draws a rectangle. In essence, sending a message to an object evokes a different response, depending on the object. This is the essence of polymorphism.

circle.draw(); // draws a circle rectangle.draw(); // draws a rectangle

Let’s look at some code to illustrate how Rectangle and Circle conform to the Shape contract. Here is the code for the Shape class:

public abstract class Shape {

public abstract void draw(); // no implementation

}

Note that the class does not provide any implementation for draw(); basically there is no code, and this is what makes the method abstract (providing any code would make the method concrete). There are two reasons why there is no implementation. First, Shape does not know what to draw, so we could not implement the draw() method even if we wanted to.

Structured Analogy

This is an interesting issue. If we did want the Shape class to contain the code for all possible shapes, present and future, conditional statements, such as a Java switch statement, would be required. This would be very messy and difficult to maintain. This is one example of where the strength of an object-oriented design comes into play.

Second, we want the subclasses to provide the implementation. Let’s look at the Circle and Rectangle classes:

public class Circle extends Shape {

public void Draw() {System.out.println ("Draw a Circle")};

}

public class Rectangle extends Shape {

public void Draw() {System.out.println ("Draw a Rectangle")};

}

Note that both Circle and Rectangle extend (that is, inherit from) Shape. Also notice that they provide the actual implementation (in this case, the implementation is trivial). Here is where the contract comes in. If Circle inherits from Shape and fails to provide a draw() method, Circle won’t even compile. Thus, Circle would fail to satisfy the contract with Shape. A project manager can require that programmers creating shapes for the application must inherit from Shape. By doing this, all shapes in the application will have a draw() method that performs in an expected manner.

Circle

If Circle does indeed fail to implement a draw() method, Circle will be considered abstract itself. Thus, yet another subclass must inherit from Circle and implement a draw() method. This subclass would then become the concrete implementation of both Shape and Circle.

Although the concept of abstract classes revolves around abstract methods, nothing is stopping Shape from providing some implementation. Remember that the definition for an abstract class is that it contains one or more abstract methods—this implies that an abstract class can also provide concrete methods. For example, although Circle and Rectangle implement the draw() method differently, they share the same mechanism for setting the color of the shape. So, the Shape class can have a color attribute and a method to set the color. This setColor() method is a concrete implementation and would be inherited by both Circle and Rectangle. The only methods that a subclass must implement are the ones that the superclass declares as abstract. These abstract methods are the contract.

Caution

Be aware that in the cases of Shape, Circle, and Rectangle, we are dealing with a strict inheritance relationship, as opposed to an interface, which we discuss in the next section. Circle is-a Shape, and Rectangle is-a Shape.

Some languages, such as C++, use only abstract classes to implement contracts; however, Java and .NET have another mechanism that implements a contract called an interface. In other cases, such as Objective-C and Swift, abstract classes are not provided by the language. Thus, to implement a contract in Objective-C or Swift, you need to use protocols.

Interfaces

Before defining an interface, it is interesting to note that C++ does not have a construct called an interface. When using C++, you can essentially create an interface by using a syntax subset of an abstract class. For example, the following C++ code is an abstract class. However, because the only method in the class is a virtual method, there is no implementation. As a result, this abstract class provides the same functionality as an interface.

class Shape

{

public:

virtual void draw() = 0;

}

Interface Terminology

This is another one of those times when software terminology gets confusing—very confusing. Be aware that you can use the term interface in several ways, so be sure to use each in the proper context.

First, the graphical user interface (GUI) is widely used when referring to the visual interface that a user interacts with—often on a monitor.

Second, the interface to a class is basically the signatures of its methods.

Third, in Objective-C and Swift, you break up the code into physically separate modules called the interface and implementation.

Fourth, an interface and a protocol are basically a contract between a parent class and a child class.Can you think of any others?

The obvious question is this: If an abstract class can provide the same functionality as an interface, why do Java and .NET bother to provide this construct called an interface? And why does Objective-C and Swift provide the protocol?

For one thing, C++ supports multiple inheritance, whereas Java, Objective-C, Swift, and .NET do not. Although Java, Objective-C, Swift, and .NET classes can inherit from only one parent class, they can implement many interfaces. Using more than one abstract class constitutes multiple inheritance; thus, Java and .NET cannot go this route. In short, when using an interface, you do not have to concern yourself with a formal inheritance structure—you can theoretically add an interface to any class if the design makes sense. However, an abstract class requires you to inherit from that abstract class and, by extension, all of its potential parents.

Circle

Because of these considerations, interfaces are often thought to be a workaround for the lack of multiple inheritance. This is not technically true. Interfaces are a separate design technique, and although they can be used to design applications that could be done with multiple inheri-tance, they do not replace or circumvent multiple inheritance.

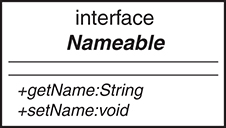

As with abstract classes, interfaces are a powerful way to enforce contracts for a framework. Before we get into any conceptual definitions, it’s helpful to see an actual interface UML diagram and the corresponding code. Consider an interface called Nameable, as shown in Figure 8.4.

Note that Nameable is identified in the UML diagram as an interface, which distinguishes it from a regular class (abstract or not). Also note that the interface contains two methods, getName() and setName(). Here is the corresponding code:

public interface Nameable {

String getName();

void setName (String aName);

}

For comparison purposes, here is the code for the corresponding Objective-C protocol:

@protocol Nameable @required - (char *) getName; - (void) setName: (char *) n; @end // Nameable

In the code, notice that Nameable is not declared as a class but as an interface. Because of this, both methods, getName() and setName(), are considered abstract and no implementation is provided. An interface, unlike an abstract class, can provide no implementation at all. As a result, any class that implements an interface must provide the implementation for all methods. For example, in Java, a class inherits from an abstract class, whereas a class implements an interface.

Implementation Versus Definition Inheritance

Sometimes inheritance is referred to as implementation inheritance, and interfaces are called definition inheritance.

Tying It All Together

If both abstract classes and interfaces provide abstract methods, what is the real difference between the two? As we saw before, an abstract class can provides both abstract and concrete methods, whereas an interface provides only abstract methods. Why is there such a difference?

Assume that we want to design a class that represents a dog, with the intent of adding more mammals later. The logical move would be to create an abstract class called Mammal:

public abstract class Mammal {

public void generateHeat() {System.out.println("Generate heat");}

public abstract void makeNoise();

}

This class has a concrete method called generateHeat()and an abstract method called makeNoise(). The method generateHeat()is concrete because all mammals generate heat. The method makeNoise()is abstract because each mammal will make noise differently.

Let’s also create a class called Head that we will use in a composition relationship:

public class Head {

String size;

public String getSize() {

return size;

}

public void setSize(String aSize) { size = aSize; }

}

Head has two methods: getSize() and setSize(). Although composition might not shed much light on the difference between abstract classes and interfaces, using composition in this example does illustrate how composition relates to abstract classes and interfaces in the overall design of an object-oriented system. I feel that this is important because the example is more complete. Remember that there are two ways to build object relationships: the is-a relationship, represented by inheritance, and the has-a relationship, represented by composition. The question is: Where does the interface fit in?

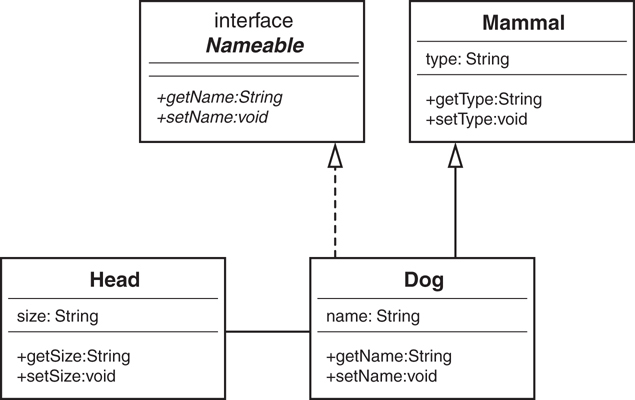

To answer this question and tie everything together, let’s create a class called Dog that is a subclass of Mammal, implements Nameable, and has a Head object (see Figure 8.5).

In a nutshell, Java and .NET build objects in three ways: inheritance, interfaces, and composition. Note the dashed line in Figure 8.5 that represents the interface. This example illustrates when you should use each of these constructs. When do you choose an abstract class? When do you choose an interface? When do you choose composition? Let’s explore further.

You should be familiar with the following concepts:

Dogis aMammal, so the relationship is inheritance.DogimplementsNameable, so the relationship is an interface.Doghas aHead, so the relationship is composition.

The following code shows how you would incorporate an abstract class and an interface in the same class:

public class Dog extends Mammal implements Nameable {

String name;

Head head;

public void makeNoise(){System.out.println("Bark");}

public void setName (String aName) {name = aName;}

public String getName () {return (name);}

}

After looking at the UML diagram, you might come up with an obvious question: Even though the dashed line from Dog to Nameable represents an interface, isn’t it still inheritance? At first glance, the answer is not simple. Although interfaces may well be considered a special type of inheritance, it is important to know what special means. Understanding these special differences is key to understanding a solid object-oriented design.

Although inheritance is a strict is-a relationship, an interface is not quite. For example:

A dog is a mammal.

A reptile is not a mammal.

Thus, a Reptile class could not inherit from the Mammal class. However, an interface transcends the various classes. For example:

A dog is nameable.

A lizard is nameable.

The key here is that classes in a strict inheritance relationship must be related. For example, in this design, the Dog class is directly related to the Mammal class. A dog is a mammal. Dogs and lizards are not related at the mammal level because you can’t say that a lizard is a mammal. However, interfaces can be used for classes that are not related. You can name a dog just as well as you can name a lizard. This is the key difference between using an abstract class and using an interface.

The abstract class represents some sort of implementation. In fact, we saw that Mammal provided a concrete method called generateHeat(). Even though we do not know what kind of mammal we have, we know that all mammals generate heat. However, an interface models only behavior. An interface never provides any type of implementation, only behavior. The interface specifies behavior that is the same across classes that conceivably have no connection. Not only are dogs nameable, but so are cars, planets, and so on.

Some say that interfaces are a poor substitute for multiple inheritance. While it may be true that interfaces were part of the same Java design that eliminated multiple inheritance (and were adopted by many other languages), interfaces are used in different design situations than inheritance, as the Nameable example illustrates.

The Compiler Proof

Can we prove or disprove that interfaces have a true is-a relationship? In the case of Java (and this can also be done in C# or VB), we can let the compiler tell us. Consider the following code:

Dog D = new Dog(); Head H = D;

When this code is run through the compiler, the following error is produced:

Test.java:6: Incompatible type for Identifier. Can't convert Dog to Head. Head H = D;

Obviously, a dog is not a head. Not only do we know this, but the compiler agrees. However, as expected, the following code works just fine:

Dog D = new Dog(); Mammal M = D;

This is a true inheritance relationship, and it is not surprising that the compiler parses this code cleanly because a dog is a mammal.

Now we can perform the true test of the interface. Is an interface an actual is-a relationship? The compiler thinks so:

Dog D = new Dog(); Nameable N = D;

This code works fine. So, we can safely say that a dog is a nameable entity. This is a simple but effective proof that both inheritance and interfaces constitute an is-a relationship. The interface relationship is more like a “behaves-like-a” when used properly. You might have data interfaces that are “is-a,” but more often you are going to have the former.

Nameable Interface

An interface specifies certain behavior but not the implementation. By implementing the Nameable interface, you are saying that you will provide nameable behavior by implementing methods called getName() and setName(). How you implement these methods is up to you. All you have to do is to provide the methods.

Making a Contract

The simple rule for defining a contract is to provide an unimplemented method, via either an abstract class or an interface. Thus, when a subclass is designed with the intent of complying with the contract, it must provide the implementation for the unimplemented methods in the parent class or interface.

As stated earlier, one of the advantages of a contract is to standardize coding conventions. Let’s explore this concept in greater detail by providing an example of what happens when coding standards are not used. In this case, there are three classes: Planet, Car, and Dog. Each class implements code to name the entity. However, because they are all implemented separately, each class has different syntax to retrieve the name. Consider the following code for the Planet class:

public class Planet {

String planetName;

public void getPlanetName() {return planetName;};

}

Likewise, the Car class might have code like this:

public class Car {

String carName;

public String getCarName() { return carName; };

}

And the Dog class might have code like this:

public class Dog {

String dogName;

public String getDogName() { return dogName; };

}

The obvious issue here is that anyone using these classes would have to look at the documentation (what a horrible thought!) to figure out how to retrieve the name in each of these cases. Even though looking at the documentation is not the worst fate in the world, it would be nice if all the classes used in a project (or company) would use the same naming convention—it would make life a bit easier. This is where the Nameable interface comes in.

The idea would be to make a contract for any type of class that needs to use a name. As users of various classes move from one class to the other, they would not have to figure out the current syntax for naming an object. The Planet class, the Car class, and the Dog class would all have the same naming syntax.

To implement this lofty goal, we can create an interface (we can use the Nameable interface that we used previously). The convention is that all classes must implement Nameable. In this way, the users have to remember only a single interface for all classes when it comes to naming conventions:

public interface Nameable {

public String getName();

public void setName(String aName);

}

The new classes, Planet, Car, and Dog, should look like this:

public class Planet implements Nameable {

String planetName;

public String getName() {return planetName;}

public void setName(String myName) { planetName = myName; }

}

public class Car implements Nameable {

String carName;

public String getName() {return carName;}

public void setName(String myName) { carName = myName;}

}

public class Dog implements Nameable {

String dogName;

public String getName() {return dogName;}

public void setName(String myName) { dogName = myName;}

}

In this way, we have a standard interface, and we’ve used a contract to ensure that it is the case. In fact, one of the major benefits of using a modern IDE is that, when implementing an interface, the IDE will automatically stub out the required methods. This feature saves lots of time and effort when using interfaces.

There is one little issue that you might have thought about. The idea of a contract is great as long as everyone plays by the rules, but what if some shady individual doesn’t want to play by the rules (the rogue programmer)? The bottom line is that there is nothing to stop people from breaking the standard contract; however, in some cases, doing so will get them in deep trouble.

On one level, a project manager can insist that everyone use the contract, just like team members must use the same variable naming conventions and configuration management system. If a team member fails to abide by the rules, he could be reprimanded, or even fired.

Enforcing rules is one way to ensure that contracts are followed, but there are instances in which breaking a contract will result in unusable code. Consider the Java interface Runnable. Old-style Java applets implement the Runnable interface because it requires that any class implementing Runnable must implement a run()method. This is important because the browser that calls the applet will call the run() method within Runnable. If the run()method does not exist, things will break.

System Plug-in Points

Basically, contracts are “plug-in points” into your code. Anyplace where you want to make parts of a system abstract, you can use a contract. Instead of coupling to objects of specific classes, you can connect to any object that implements the contract. You need to be aware of where contracts are useful; however, you can overuse them. You want to identify common features such as the Nameable interface, as discussed in this chapter. However, be aware that there is a trade-off when using contracts. They might make code reuse more of a reality, but they make things somewhat more complex.

An E-Business Example

It’s sometimes hard to convince a decision maker, who may have no development background, of the monetary savings of code reuse. However, when reusing code, it is pretty easy to understand the advantage to the bottom line. In this section, we’ll walk through a simple but practical example of how to create a workable framework using inheritance, abstract classes, interfaces, and composition.

An E-Business Problem

Perhaps the best way to understand the power of reuse is to present an example of how you would reuse code. In this example, we’ll use inheritance (via interfaces and abstract classes) and composition. Our goal is to create a framework that will make code reuse a reality, reduce coding time, and reduce maintenance—all the typical software development wish-list items.

Let’s start our own Internet business. Let’s assume that we have a client, a small pizza shop called Papa’s Pizza. Despite the fact that it is a small, family-owned business, Papa realizes that a Web presence can help the business in many ways. Papa wants his customers to access his website, find out what Papa’s Pizza is all about, and order pizzas right from the comfort of their browsers.

At the site we develop, customers will be able to access the website, select the products they want to order, and select a delivery option and time for delivery. They can eat their food at the restaurant, pick up the order, or have the order delivered. For example, a customer decides at 3:00 that he wants to order a pizza dinner (with salads, breadsticks, and drinks), to be delivered to his home at 6:00. Let’s say the customer is at work (on a break, of course). He gets on the Web and selects the pizzas, including size, toppings, and crust; the salads, including dressings; breadsticks; and drinks. He chooses the delivery option and requests that the food be delivered to his home at 6:00. Then he pays for the order by credit card, gets a confirmation number, and exits. Within a few minutes he gets an email confirmation as well. We will set up accounts so that when people bring up the site, they will get a greeting reminding them of who they are, what their favorite pizza is, and what new pizzas have been created this week.

When the software system is finally delivered, it is deemed a total success. For the next several weeks, Papa’s customers happily order pizzas and other food and drinks over the Internet. During this rollout period, Papa’s brother-in-law, who owns a donut shop called Dad’s Donuts, pays Papa a visit. Papa shows Dad the system, and Dad falls in love with it. The next day, Dad calls our company and asks us to develop a Web-based system for his donut shop. This is great, and exactly what we had hoped for. Now, how can we leverage the code that we used for the pizza shop in the system for the donut shop?

How many more small businesses, besides Papa’s Pizza and Dad’s Donuts, could take advantage of our framework to get on the Web? If we can develop a good, solid framework, we will be able to efficiently deliver Web-based systems at lower costs than we were able to do before. There will also be an added advantage that the code will have been tested and implemented previously, so debugging and maintenance should be greatly reduced.

The Non-Reuse Approach

For many reasons, the concept of code reuse has not been as successful as some software developers would like. First, many times reuse is not even considered when developing a system. Second, even when reuse is entered into the equation, the issues of schedule constraints, limited resources, and budgetary concerns often short-circuit the best intentions.

In many instances, code ends up highly coupled to the specific application for which it was written. This means that the code within the application is highly dependent on other code within the same application.

A lot of code reuse is the result of using cut, copy, and paste operations. While one application is open in a text editor, you copy code and then paste it into another application. Sometimes certain functions or routines can be used without any change. As is unfortunately often the case, even though most of the code may remain identical, a small bit of code must change to work in a specific application.

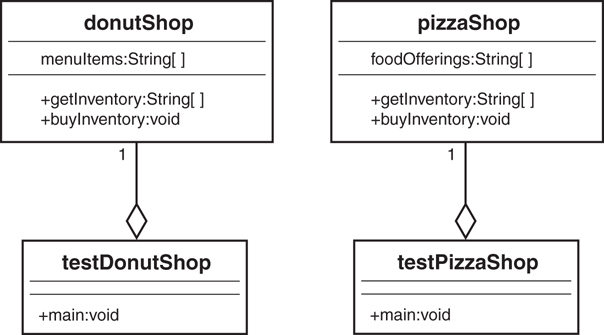

For example, consider two separate applications, as represented by the UML diagram in Figure 8.6.

In this example, the applications testDonutShop and testPizzaShop are totally independent code modules. The code is kept separate, and there is no interaction between the modules. However, these applications might use some common code. In fact, some code might have been copied verbatim from one application to another. At some point, someone involved with the project might decide to create a library of these shared pieces of code to use in these and other applications. In many well-run and disciplined projects, this approach works well. Coding standards, configuration management, change management, and so on are all very well run. However, in many instances, this discipline breaks down.

Anyone who is familiar with the software development process knows that when bugs crop up and time is of the essence, there is the temptation to put some fixes or additions into a system that are specific to the application currently in distress. This might fix the problem for the distressed application but could have unintended, possibly harmful, implications for other applications. Thus, in situations like these, the initially shared code can diverge, and separate code bases must be maintained.

For example, one day Papa’s website crashes. He calls us in a panic, and one of our developers is able to track down the problem. The developer fixes the problem, knowing that the fix works but is not quite sure why. The developer also does not know what other areas of the system the fix might inadvertently affect. So the developer makes a copy of the code, strictly for use in the Papa’s Pizza system. This is affectionately named Version 2.01papa. Because the developer does not yet totally understand the problem and because Dad’s system is working fine, the code is not migrated to the donut shop’s system.

Tracking Down a Bug

The fact that the bug turned up in the pizza system does not mean that it will also turn up in the donut system. Even though the bug caused a crash in the pizza shop, the donut shop might never encounter it. It may be that the fix to the pizza shop's code is more dangerous to the donut shop than the original bug.

The next week Dad calls in a panic, with a totally unrelated problem. A developer fixes it, again not knowing how the fix will affect the rest of the system, makes a separate copy of the code, and calls it Version 2.03dad. This scenario gets played out for all the sites we now have in operation. There are now a dozen or more copies of the code, with various versions for the various sites. This becomes a mess. We have multiple code paths and have crossed the point of no return. We can never merge them again. (Perhaps we could, but from a business perspective, this would be costly.)

Our goal is to avoid the mess of the previous example. Although many systems must deal with legacy issues, fortunately for us, the pizza and donut applications are brand-new systems. Thus, we can use a bit of foresight and design this system in a reusable manner. In this way, we will not run into the maintenance nightmare just described. What we want to do is factor out as much commonality as possible. In our design, we will focus on all the common business functions that exist in a Web-based application. Instead of having multiple application classes like testPizzaShop and testDonutShop, we can create a design that has a class called Shop that all the applications will use.

Notice that testPizzaShop and testDonutShop have similar interfaces, getInventory() and buyInventory(). We will factor out this commonality and require that all applications that conform to our Shop framework implement getInventory() and buyInventory() methods. This requirement to conform to a standard is sometimes called a contract. By explicitly setting forth a contract of services, you isolate the code from a single implementation. In Java, you can implement a contract by using an interface or an abstract class. Let’s explore how this is accomplished.

An E-Business Solution

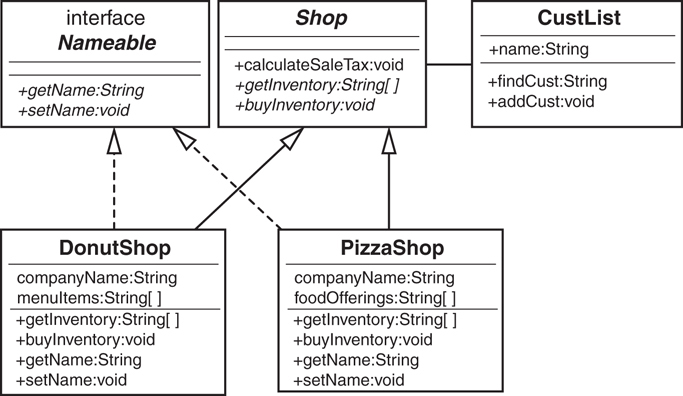

Now let’s show how to use a contract to factor out some of the commonality of these systems. In this case, we will create an abstract class to factor out some of the implementation, and an interface (our familiar Nameable) to factor out some behavior.

Our goal is to provide customized versions of our Web application with the following features:

An interface, called

Nameable, which is part of the contract.An abstract class, called

Shop, which is also part of the contract.A class called

CustList, which we use in composition.A new implementation of

Shopfor each customer we service.

The UML Object Model

The newly created Shop class is where the functionality is factored out. Notice in Figure 8.7 that the methods getInventory() and buyInventory() have been moved up the hierarchy tree from DonutShop and PizzaShop to the abstract class Shop. Now, whenever we want to provide a new, customized version of Shop, we plug in a new implementation of Shop (such as a grocery shop). Shop is the contract that the implementations must abide by.

public abstract class Shop {

CustList customerList;

public void CalculateSaleTax() {

System.out.println("Calculate Sales Tax");

}

public abstract String[] getInventory();

public abstract void buyInventory(String item);

}

Shop model.

To show how composition fits into this picture, the Shop class has a customer list. Thus, the class CustList is contained within Shop:

public class CustList {

String name;

public String findCust() {return name;}

public void addCust(String Name){}

}

To illustrate the use of an interface in this example, an interface called Nameable is defined:

public interface Nameable {

public abstract String getName();

public abstract void setName(String name);

}

We could potentially have a large number of different implementations, but all the rest of the code (the application) is the same. In this small example, the code savings might not look like a lot. But in a large, real-world application, the code savings is significant. Let’s take a look at the donut shop implementation:

public class DonutShop extends Shop implements Nameable {

String companyName;

String[] menuItems = {

"Donuts",

"Muffins",

"Danish",

"Coffee",

"Tea"

};

public String[] getInventory() {

return menuItems;

}

public void buyInventory(String item) {

System.out.println("

You have just purchased " + item);

}

public String getName(){

return companyName;

}

public void setName(String name){

companyName = name;

}

}

The pizza shop implementation looks very similar:

public class PizzaShop extends Shop implements Nameable {

String companyName;

String[] foodOfferings = {

"Pizza",

"Spaghetti",

"Garden Salad",

"Antipasto",

"Calzone"

}

public String[] getInventory() {

return foodOfferings;

}

public void buyInventory(String item) {

System.out.println("

You have just purchased " + item);

}

public String getName(){

return companyName;

}

public void setName(String name){

companyName = name;

}

}

Unlike the initial case, where a large number of customized applications exist, we now have only a single primary class (Shop) and various customized classes (PizzaShop, DonutShop). There is no coupling between the application and any of the customized classes. The only thing the application is coupled to is the contract (Shop). The contract specifies that any implementation of Shop must provide an implementation for two methods, getInventory() and buyInventory(). It also must provide an implementation for getName() and setName() that relates to the interface Nameable that is implemented.

Although this solution solves the problem of highly coupled implementations, we still have the problem of deciding which implementation to use. With the current strategy, we would still have to have separate applications. In essence, you must provide one application for each Shop implementation. Even though we are using the Shop contract, we still have the same situation as before we used the contract:

DonutShop myShop= new DonutShop(); PizzaShop myShop = new PizzaShop ();

How do we get around this problem? We can create objects dynamically. In Java, we can use code like this:

String className = args[0]; Shop myShop; myShop = (Shop)Class.forName(className).newInstance();

In this case, you set className by passing a parameter to the code. (There are other ways to set className, such as by using a system property.)

Let’s look at Shop using this approach. (Note that there is no exception handling and nothing else besides object instantiation.)

class TestShop {

public static void main (String args[]) {

Shop shop = null;

String className = args[0];

System.out.println("Instantiate the class:" + className + "

");

try {

// new pizzaShop();

shop = (Shop)Class.forName(className).newInstance();

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

String[] inventory = shop.getInventory();

// list the inventory

for (int i=0; i<inventory.length; i++) {

System.out.println("Argument" + i + " = " + inventory[i]);

}

// buy an item

shop.buyInventory(Inventory[1]);

}

}

In this way, we can use the same application code for both PizzaShop and DonutShop. If we add a GroceryShop application, we only have to provide the implementation and the appropriate string to the main application. No application code needs to change.

Conclusion

When designing classes and object models, it is vitally important to understand how the objects are related to each other. This chapter discusses the primary topics of building objects: inheritance, interfaces, and composition. In this chapter, you have learned how to build reusable code by designing with contracts.

In Chapter 9, “Building Objects and Object-Oriented Design,” we complete our OO journey and explore how objects that might be totally unrelated can interact with each other.

References

Booch, Grady and Robert A. Maksimchuk and Michael W. Engel and Bobbi J. Young and Jim Conallen and Kelli A. Houston. 2007. Object-Oriented Analysis and Design with Applications, Third Edition. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Coad, Peter, and Mark Mayfield. 1997. Java Design. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Meyers, Scott. 2005. Effective C++, Third Edition. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley Professional.