3. More Object-Oriented Concepts

Chapter 1, “Introduction to Object-Oriented Concepts,” and Chapter 2, “How to Think in Terms of Objects,” cover the basics of object-oriented (OO) concepts. Before we embark on our journey to learn some of the finer design issues relating to building an OO system, we need to cover a few more advanced OO concepts, such as constructors, operator overloading, and multiple inheritance. We also will consider error-handling techniques and how scope applies to object-oriented design.

Some of these concepts might not be vital to understanding an OO design at a higher level, but they are necessary to anyone involved in the design and implementation of an OO system.

Constructors

Constructors may be a new concept for structured programmers. Although constructors are not normally used in non-OO languages such as COBOL, C, and Basic, the struct, which is part of C/C++, does include constructors. In the first two chapters we alluded to these special methods that are used to construct objects. In some OO languages, such as Java and C#, constructors are methods that share the same name as the class. Visual Basic .NET uses the designation New and Swift uses the init keyword. As usual, we will focus on the concepts of constructors and not cover the specific syntax of all the languages. Let’s take a look at some Java code that implements a constructor.

For example, a constructor for the Cabbie class we covered in Chapter 2 would look like this:

public Cabbie(){

/* code to construct the object */

}

The compiler will recognize that the method name is identical to the class name and consider the method a constructor.

Caution

Note that in this Java code (as with C# and C++), a constructor does not have a return value. If you provide a return value, the compiler will not treat the method as a constructor.

For example, if you include the following code in the class, the compiler will not consider this a constructor because it has a return value—in this case an integer.

public int Cabbie(){

/* code to construct the object */

}

This syntax requirement can cause problems because this code will compile but will not behave as expected.

When Is a Constructor Called?

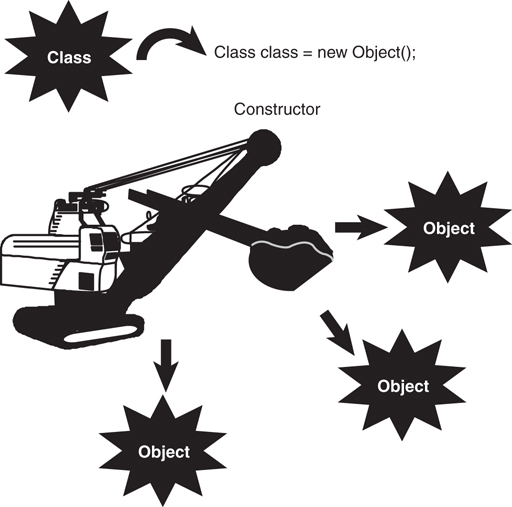

When a new object is created, one of the first things that happens is that the constructor is called. Check out the following code:

Cabbie myCabbie = new Cabbie();

The new keyword creates a new instance of the Cabbie class, thus allocating the required memory. Then the constructor itself is called, passing the arguments in the parameter list. The constructor provides the developer the opportunity to attend to the appropriate initialization.

Thus, the code new Cabbie() will instantiate a Cabbie object and call the Cabbie method, which is the constructor.

What’s Inside a Constructor?

Perhaps the most important function of a constructor is to initialize the memory allocated when the new keyword is encountered. In short, code included inside a constructor should set the newly created object to its initial, stable, safe state.

For example, if you have a counter object with an attribute called count, you need to set count to zero in the constructor:

count = 0;

Initializing Attributes

In structured programming, a routine named housekeeping (or initialization) is often used for initialization purposes. Initializing attributes is a common function performed within a constructor. Regardless, don't rely on the system defaults.

The Default Constructor

If you write a class and do not include a constructor, the class will still compile, and you can still use it. If the class provides no explicit constructor, a default constructor will be provided. It is important to understand that at least one constructor always exists, regardless of whether you write a constructor yourself. If you do not provide a constructor, the system will provide a default constructor for you.

Besides the creation of the object itself, the only action that a default constructor takes is to call the constructor of its superclass. In many cases, the superclass will be part of the language framework, like the Object class in Java. For example, if a constructor is not provided for the Cabbie class, the following default constructor is inserted:

public Cabbie(){

super();

}

If you were to decompile the bytecode produced by the compiler, you would see this code. The compiler actually inserts it.

In this case, if Cabbie does not explicitly inherit from another class, the Object class will be the parent class. Perhaps the default constructor might be sufficient in some cases; however, in most cases some sort of memory initialization should be performed. Regardless of the situation, it is good programming practice to always include at least one constructor in a class. If there are attributes in the class, it is always good practice to initialize them. Moreover, initializing variables is always a good practice when writing code, object-oriented or not.

Providing a Constructor

The general rule is that you should always provide a constructor, even if you do not plan to do anything inside it. You can provide a constructor with nothing in it and then add to it later. Although there is technically nothing wrong with using the default constructor provided by the compiler, for documentation and maintenance purposes, it is always nice to know exactly what your code looks like.

It is not surprising that maintenance becomes an issue here. If you depend on the default constructor and then subsequent maintenance adds another constructor, the default constructor is no longer created. This may actually break code that was assuming the presence of a default constructor.

Always remember that the default constructor is added only if you don’t include any constructors. As soon as you include just one, the default constructor is not provided.

Using Multiple Constructors

In many cases, an object can be constructed in more than one way. To accommodate this situation, you need to provide more than one constructor. For example, let’s consider the Count class presented here:

public class Count {

int count;

public Count(){

count = 0;

}

}

On the one hand, we want to initialize the attribute count to count to zero: We can easily accomplish this by having a constructor initialize count to zero as follows:

public Count(){

count = 0;

}

On the other hand, we might want to pass an initialization parameter that allows count to be set to various numbers:

public Count (int number){

count = number;

}

This is called overloading a method (overloading pertains to all methods, not just constructors). Most OO languages provide functionality for overloading a method.

Overloading Methods

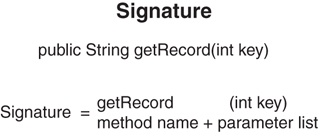

Overloading allows a programmer to use the same method name over and over, as long as the signature of the method is different each time. The signature consists of the method name and a parameter list (see Figure 3.1).

Thus, the following methods all have different signatures:

public void getCab(); // different parameter list public void getCab (String cabbieName); // different parameter list public void getCab (int numberOfPassengers);

Signatures

Depending on the language, the signature may or may not include the return type. In Java and C#, the return type is not part of the signature. For example, the following methods would conflict even though the return types are different:

public void getCab (String cabbieName); public int getCab (String cabbieName);

The best way to understand signatures is to write some code and run it through the compiler.

By using different signatures, you can construct objects differently depending on the constructor used. This functionality is very helpful when you don’t always know ahead of time how much information you have available. For example, when creating a shopping cart, customers may already be logged in to their account (and you will have all of their information). On the other hand, a totally new customer may be placing items in the cart with no account information available at all. In each case the constructor would initialize differently.

Using UML to Model Classes

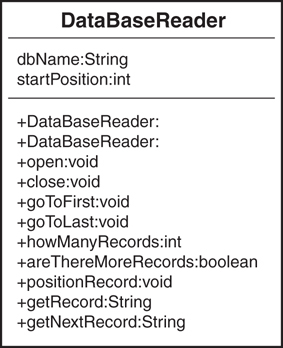

Let’s return to the database reader example we used earlier in Chapter 2. Consider that we have two ways we can construct a database reader:

Pass the name of the database and position the cursor at the beginning of the database.

Pass the name of the database and the position within the database where we want the cursor to position itself.

Figure 3.2 shows a class diagram for the DataBaseReader class. Note that the diagram lists two constructors for the class. Although the diagram shows the two constructors, without the parameter list, there is no way to know which constructor is which. To distinguish the constructors, you can look at the corresponding code in the DataBaseReader class listed next.

DataBaseReader class diagram.

No Return Type

Notice that in this class diagram the constructors do not have a return type. All other methods besides constructors must have return types.

Here is a code segment of the class that shows its constructors and the attributes that the constructors initialize (see Figure 3.3):

public class DataBaseReader {

String dbName;

int startPosition;

// initialize just the name

public DataBaseReader (String name){

dbName = name;

startPosition = 0;

};

// initialize the name and the position

public DataBaseReader (String name, int pos){

dbName = name;

startPosition = pos;

};

.. // rest of class

}

Note how startPosition is initialized in both cases. If the constructor is not passed the information via the parameter list, it is initialized to a default value, such as 0.

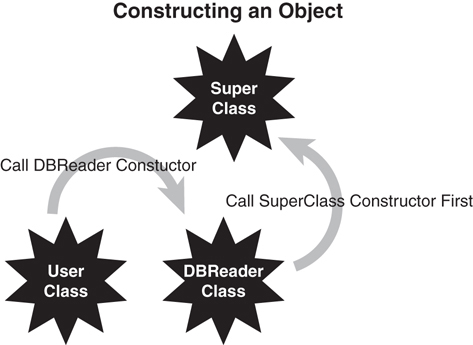

How the Superclass Is Constructed

When using inheritance, you must know how the parent class is constructed. Remember that when you use inheritance, you are inheriting everything about the parent. Thus, you must become intimately aware of all the parent’s data and behavior. The inheritance of an attribute is fairly obvious; however, how a constructor is inherited is not as obvious. After the new keyword is encountered and the object is allocated, the following steps occur (see Figure 3.4):

Inside the constructor, the constructor of the class’s superclass is called. If there is no explicit call to the superclass constructor, the default is called automatically; however, you can see the code in the bytecodes.

Each class attribute of the object is initialized. These are the attributes that are part of the class definition (instance variables), not the attributes inside the constructor or any other method (local variables). In the

DataBaseReadercode presented earlier, the integerstartPositionis an instance variable of the class.The rest of the code in the constructor executes.

The Design of Constructors

As we have already seen, when designing a class, it is good practice to initialize all the attributes. In some languages, the compiler provides some sort of initialization. As always, don’t count on the compiler to initialize attributes! In Java, you cannot use an attribute until it is initialized. If the attribute is first set in the code, make sure that you initialize the attribute to some valid condition—for example, set an integer to zero.

Constructors are used to ensure that the application is in a stable state (I like to call it a “safe” state). For example, initializing an attribute to zero, when it is intended for use as a denominator in a division operation, might lead to an unstable application. You must take into consideration that a division by zero is an illegal operation. Initializing to zero is not always the best policy.

During the design, it is good practice to identify a stable state for all attributes and then initialize them to this stable state in the constructor.

Error Handling

It is extremely rare for a class to be written perfectly the first time. In most, if not all, situations, things will go wrong. Any developer who does not plan for problems is inviting disaster.

Assuming that your code has the capability to detect and trap an error condition, you can handle the error in several ways: In Chapter 11 of their book Java Primer Plus, Tyma, Torok, and Downing (ISBN: 9781571690623) state that there are three basic solutions to handling problems that are detected in a program: fix it, ignore the problem by squelching it, or exit the runtime in some graceful manner. In Chapter 4 of their book Object-Oriented Design in Java (ISBN: 9781571691347), Gilbert and McCarty expand on this theme by adding the choice of throwing an exception:

Ignore the problem—not a good idea!

Check for potential problems and abort the program when you find a problem.

Check for potential problems, catch the mistake, and attempt to fix the problem.

Throw an exception. (Often this is the preferred way to handle the situation.)

These strategies are discussed in the following sections.

Ignoring the Problem

Simply ignoring a potential problem is a recipe for disaster. And if you are going to ignore the problem, why bother detecting it in the first place? It is obvious that you should not ignore any known problem. The primary directive for all applications is that the application should never crash. If you do not handle your errors, the application will eventually terminate ungracefully or continue in a mode that can be considered an unstable state—possibly with corrupted data. In the latter case, you might not even know you are getting incorrect results, and that can be much worse than a program crash.

Checking for Problems and Aborting the Application

If you choose to check for potential problems and abort the application when a problem is detected, the application can display a message indicating that a problem exists. In this case the application gracefully exits, and the user is left staring at the computer screen, shaking her head and wondering what just happened. Although this is a far superior option to ignoring the problem, it is by no means optimal. However, this does allow the system to clean up things and put itself in a more stable state, such as closing files and forcing a system restart.

Checking for Problems and Attempting to Recover

Checking for potential problems, catching the mistake, and attempting to recover is a far superior solution than simply checking for problems and aborting. In this case, the problem is detected by the code, and the application attempts to fix itself. This works well in certain situations. For example, consider the following code:

if (a == 0)

a=1;

c = b/a;

It is obvious that if the conditional statement is not included in the code, and a zero makes its way to the divide statement, you will get a system exception because you cannot divide by zero. By catching the exception and setting the variable a to 1, at least the system will not crash. However, setting a to 1 might not be a proper solution because the result would be incorrect. The better solution would be to prompt the user to reenter the proper input value.

A Mix of Error-Handling Techniques

Despite the fact that this type of error handling is not necessarily object-oriented in nature, I believe that it has a valid place in OO design. Throwing an exception (discussed inthe next section) can be expensive in terms of overhead. Thus, although exceptions may be a valid design choice, you will still want to consider other error-handling techniques (even tried-and-true structured techniques), depending on your design and performance needs.

Although the error checking techniques mentioned previously are preferable to doing nothing, they still have a few problems. It is not always easy to determine where a problem first appears. And it might take a while for the problem to be detected. In any event, it is beyond the scope of this book to explain error handling in great detail. However, it is important to design error handling into the class right from the start, and often the operating system itself can alert you to problems that it detects.

Throwing an Exception

Most OO languages provide a feature called exceptions. In the most basic sense, exceptions are unexpected events that occur within a system. Exceptions provide a way to detect problems and then handle them. In Java, C#, C++, Swift, and Visual Basic, exceptions are handled by the keywords catch and throw. This might sound like a baseball game, but the key concept here is that a specific block of code is written to handle a specific exception. This solves the problem of trying to figure out where the problem started and unwinding the code to the proper point.

Here is the structure for a Java try/catch block:

try {

// possible nasty code

} catch(Exception e) {

// code to handle the exception

}

If an exception is thrown within the try block, the catch block will handle it. When an exception is thrown while the block is executing, the following occurs:

The execution of the

tryblock is terminated.The

catchclauses are checked to determine whether an appropriatecatchblock for the offending exception was included. (There might be more than onecatchclause pertryblock.)If none of the

catchclauses handles the offending exception, it is passed to the next higher-leveltryblock. (If the exception is not caught in the code, the system ultimately catches it, and the results are unpredictable—that is, an application crash.)If a

catchclause is matched (the first match encountered), the statements in thecatchclause are executed.Execution then resumes with the statement following the

tryblock.

Suffice it to say that exceptions are an important advantage for OO programming languages. Here is an example of how an exception is caught in Java:

try {

// possible nasty code

count = 0;

count = 5/count;

} catch(ArithmeticException e) {

// code to handle the exception

System.out.println(e.getMessage());

count = 1;

}

System.out.println("The exception is handled.");

Exception Granularity

You can catch exceptions at various levels of granularity. You can catch all exceptions or check for specific exceptions, such as arithmetic exceptions. If your code does not catch an exception, the Java runtime will—and it won't be happy about it!

In this example, the division by zero (because count is equal to 0) within the try block will cause an arithmetic exception. If the exception was generated (thrown) outside a try block, the program would most likely have been terminated (crashed). However, because the exception was thrown within a try block, the catch block is checked to see whether the specific exception (in this case, an arithmetic exception) was planned for. Because the catch block contains a check for the arithmetic exception, the code within the catch block is executed, thus setting count to 1. After the catch block executes, the try/catch block is exited, and the message The exception is handled. appears on the Java console. The logical flow of this process is illustrated in Figure 3.5.

If you had not put ArithmeticException in the catch block, the program would likely have crashed. You can catch all exceptions by using the following code:

try {

// possible nasty code

} catch(Exception e) {

// code to handle the exception

}

The Exception parameter in the catch block is used to catch any exception that might be generated within the scope of a try block.

Bulletproof Code

It's a good idea to use a combination of the methods described here to make your program as bulletproof to your user as possible.

The Importance of Scope

Multiple objects can be instantiated from a single class. Each of these objects has a unique identity and state. This is an important point. Each object is constructed separately and is allocated its own separate memory. However, some attributes and methods may, if properly declared, be shared by all the objects instantiated from the same class, thus sharing the memory allocated for these class attributes and methods.

A Shared Method

A constructor is a good example of a method that is shared by all instances of aclass.

Methods represent the behaviors of an object; the state of the object is represented by attributes. There are three types of attributes:

Local attributes

Object attributes

Class attributes

Local Attributes

Local attributes are owned by a specific method. Consider the following code:

public class Number {

public method1() {

int count;

}

public method2() {

}

}

The method method1 contains a local variable called count. This integer is accessible only inside method1. The method method2 has no idea that the integer count even exists.

At this point, we introduce a very important concept: scope. Attributes (and methods) exist within a particular scope. In this case, the integer count exists within the scope of method1. In Java, C#, C++, and Swift, scope is delineated by curly braces ({}). In the Number class, there are several possible scopes—just start matching the curly braces.

The class itself has its own scope. Each instance of the class (that is, each object) has its own scope. Both method1 and method2 have their own scopes as well. Because count lives within method1’s curly braces, when method1 is invoked, a copy of count is created. When method1 terminates, the copy of count is removed.

For some more fun, look at this code:

public class Number {

public method1() {

int count;

}

public method2() {

int count;

}

}

This example has two copies of an integer count in this class. Remember that method1 and method2 each has its own scope. Thus, the compiler can tell which copy of count to access simply by recognizing which method it is in. You can think of it in these terms:

method1.count; method2.count;

As far as the compiler is concerned, the two attributes are easily differentiated, even though they have the same name. It is almost like two people having the same last name, but based on the context of their first names, you know that they are two separate individuals.

Object Attributes

In many design situations, an attribute must be shared by several methods within the same object. In Figure 3.6, for example, three objects have been constructed from a single class. Consider the following code:

public class Number {

int count; // available to both method1 and method2

public method1() {

count = 1;

}

public method2() {

count = 2;

}

}

Note here that the class attribute count is declared outside the scope of both method1 and method2. However, it is within the scope of the class. Thus, count is available to both method1 and method2. (Basically, all methods in the class have access to this attribute.) Notice that the code for both methods is setting count to a specific value. There is only one copy of count for the entire object, so both assignments operate on the same copy in memory. However, this copy of count is not shared between different objects.

To illustrate, let’s create three copies of the Number class:

Number number1 = new Number(); Number number2 = new Number(); Number number3 = new Number();

Each of these objects—number1, number2, and number3—is constructed separately and is allocated its own resources. There are three separate instances of the integer count. When number1 changes its attribute count, this in no way affects the copy of count in object number2 or object number3. In this case, integer count is an object attribute.

You can play some interesting games with scope. Consider the following code:

public class Number {

int count;

public method1() {

int count;

}

public method2() {

int count;

}

}

In this case, three totally separate memory locations have the name of count for each object. The object owns one copy, and method1() and method2() each have their own copy.

To access the object variable from within one of the methods, say method1(), you can use a pointer called this in the C-based languages:

public method1() {

int count;

this.count = 1;

}

Notice that some code looks a bit curious:

this.count = 1;

The selection of the word this as a keyword is perhaps unfortunate. However, we must live with it. The use of the this keyword directs the compiler to access the object variable count and not the local variables within the method bodies.

Note

The keyword this is a reference to the current object.

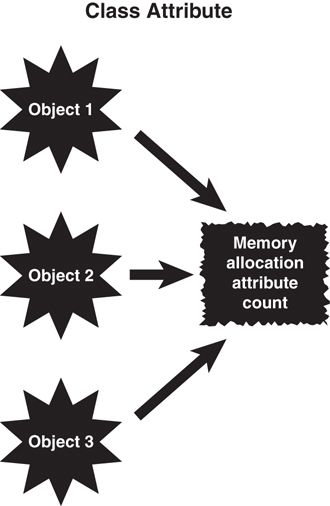

Class Attributes

As mentioned earlier, it is possible for two or more objects of the same class to share attributes. In Java, C#, C++, and Swift, you do this by making the attribute static:

public class Number {

static int count;

public method1() {

}

}

By declaring count as static, this attribute is allocated a single piece of memory for all objects instantiated from the class. Thus, all objects of the class use the same memory location for count. Essentially, each class has a single copy, which is shared by all objects of that class (see Figure 3.7). This is about as close to global data as we get in OO design.

There are many valid uses for class attributes; however, you must be aware of potential synchronization problems. Let’s instantiate two Count objects:

Count Count1 = new Count(); Count Count2 = new Count();

For the sake of argument, let’s say that the object Count1 is going merrily about its way and is using count as a means of keeping track of the pixels on a computer screen. This is not a problem until the object Count2 decides to use attribute count to keep track of sheep. The instant that Count2 records its first sheep, the data that Count1 was saving is lost. In practice, there might not be a lot of uses for static methods. Make sure you are confident in their use before incorporating them in designs.

Operator Overloading

Some OO languages enable you to overload an operator. C++ is an example of one such language. Operator overloading enables you to change the meaning of an operator. For example, when most people see a plus sign, they assume it represents addition. If you see the equation

X = 5 + 6;

you expect that X would contain the value 11. And in this case, you would be correct.

However, at times a plus sign could represent something else. For example, in the following code:

String firstName = "Joe", lastName = "Smith"; String Name = firstName + " " + lastName;

You would expect that Name would contain Joe Smith. The plus sign here has been overloaded to perform string concatenation.

String Concatenation

String concatenation occurs when two separate strings are combined to create a new, single string.

In the context of strings, the plus sign does not mean addition of integers or floats but concatenation of strings.

What about matrix addition? You could have code like this:

Matrix a, b, c; c = a + b;

Thus, the plus sign now performs matrix addition, not addition of integers or floats.

Overloading is a powerful mechanism. However, it can be downright confusing for people who read and maintain code. In fact, developers can confuse themselves. To take this to an extreme, it would be possible to change the operation of addition to perform subtraction. Why not? Operator overloading allows you to change the meaning of an operator. Thus, if the plus sign were changed to perform subtraction, the following code would result in an X value of —1.

x = 5 + 6;

OO languages such as Java and .NET do not allow operator overloading.

Although these languages do not allow the option of overloading operators, the languages themselves do overload the plus sign for string concatenation, but that’s about it. The designers of Java must have decided that operator overloading was more of a problem than it was worth. If you must use operator overloading in C++, take care by documenting and commenting properly so the people who will use the class are not confused.

Multiple Inheritance

We cover inheritance in much more detail in Chapter 7, “Mastering Inheritance and Composition.” However, this is a good place to begin discussing multiple inheritance, which is one of the more powerful and challenging aspects of class design.

As the name implies, multiple inheritance allows a class to inherit from more than one class. In practice, this seems like a great idea. Objects are supposed to model the real world, are they not? And many real-world examples of multiple inheritance exist. Parents are a good example of multiple inheritance. Each child has two parents—that’s just the way it is. So it makes sense that you can design classes by using multiple inheritance. In some OO languages, such as C++, you can.

However, this situation falls into a category similar to operator overloading. Multiple inheritance is a very powerful technique, and in fact, some problems are quite difficult to solve without it. Multiple inheritance can even solve some problems quite elegantly. However, multiple inheritance can significantly increase the complexity of a system, both for the programmer and the compiler writers.

The designers of Java, .NET, and Swift decided that the increased complexity of allowing multiple inheritance far outweighed its advantages, so they simply did not implement it. In some ways, Java, .NET, and Swift compensate for this; however, the bottom line is that Java, .NET, and Swift do not allow conventional multiple inheritance.

The modern concept of inheritance is that you can only inherit attributes from a single parent (single inheritance). Even though you can use multiple interfaces or protocols, this is not truly multiple inheritance.

Behavioral and Implementation Inheritance

Interfaces are a mechanism for behavioral inheritance, whereas abstract classes are used for implementation inheritance. The bottom line is that interface language constructs provide behavioral interfaces but no implementation, whereas abstract classes may provide both interfaces and implementation. This topic is covered in great detail in Chapter 8, “Frameworks and Reuse: Designing with Interfaces and Abstract Classes.”

Object Operations

Some of the most basic operations in programming become more complicated when you’re dealing with complex data structures and objects. For example, when you want to copy or compare primitive data types, the process is quite straightforward. However, copying and comparing objects is not quite as simple. In his book Effective C++, Scott Meyers devotes an entire section to copying and assigning objects.

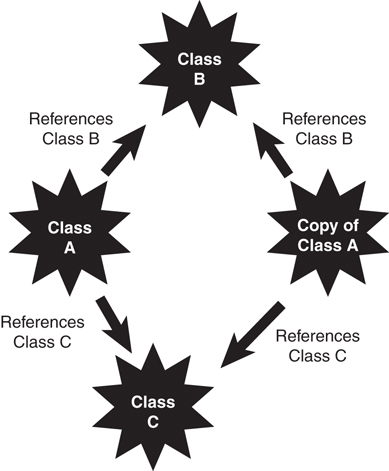

Classes and References

The problem with complex data structures and objects is that they might contain references. Simply making a copy of the reference does not copy the data structures or the object that it references. In the same vein, when comparing objects, simply comparing a pointer to another pointer only compares the references—not what they point to.

The problems arise when comparisons and copies are performed on objects. Specifically, the question boils down to whether you follow the pointers. Regardless, there should be a way to copy an object. Again, this is not as simple as it might seem. Because objects can contain references, these reference trees must be followed to do a valid copy (if you truly want to do a deep copy).

Deep Versus Shallow Copies

A deep copy occurs when all the references are followed and new copies are created for all referenced objects. Many levels might be involved in a deep copy. For objects with references to many objects, which in turn might have references to even more objects, the copy itself can create significant overhead. A shallow copy would simply copy the reference and not follow the levels. Gilbert and McCarty have a good discussion about what shallow and deep hierarchies are in Object-Oriented Design in Java in a section called “Prefer a Tree to a Forest.”

To illustrate, in Figure 3.8, if you do a simple copy of the object (called a bitwise copy), only the references are copied—not any of the actual objects. Thus, both objects (the original and the copy) will reference (point to) the same objects. To perform a complete copy, in which all reference objects are copied, you must write code to create all the subobjects.

This problem also manifests itself when comparing objects. As with the copy function, this is not as simple as it might seem. Because objects contain references, these reference trees must be followed to do a valid comparison of objects. In most cases, languages provide a default mechanism to compare objects. As is usually the case, do not count on the default mechanism. When designing a class, you should consider providing a comparison function in your class that you know will behave as you want it to.

Conclusion

This chapter covered a number of advanced OO concepts that, although perhaps not vital to a general understanding of OO concepts, are quite necessary in higher-level OO tasks, such as designing a class. In Chapter 4, “The Anatomy of a Class,” we start looking specifically at how to design and build a class.

References

Gilbert, Stephen, and Bill McCarty. 1998. Object-Oriented Design in Java. Berkeley, CA: The Waite Group Press.

Meyers, Scott. 2005. Effective C++, Third Edition. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley Professional.

Tyma, Paul, Gabriel Torok, and Troy Downing. 1996. Java Primer Plus. Berkeley, CA: The Waite Group.