SUPER BLOOM CALIFORNIA, WALKER CANYON PHANTOM 4 PRO

A bracketed HDR Panorama of the spectacular poppy super-bloom.

CHAPTER 2DRONES AND GEAR

THE MOST IMPORTANT PART OF AERIAL PHOTOGRAPHY IS THE GEAR, because without it, you can’t fly or shoot. Having said that, you don’t need the biggest, best, most expensive gear to get great shots. You just have to make sure that your equipment is able to do what you need it to do. Passion, practice, perseverance, and creativity are the key ingredients to getting winning shots. However, all the talent in the world won’t get you great aerial shots if all you are doing is throwing an iPhone up in the air as high as you can. In this chapter, we discuss the stuff gear-hounds love! We look at different drones and their features and accessories. As far as what kind of drone you fly, this particular chapter is very DJI-centric, because they are currently the leading platform. It’s what I fly and have experience with. But remember that these terms and principles apply to any drone that is available today or in the near future.

DIFFERENT PLATFORMS

EARLY ON, THE RC COMMUNITY WAS MOSTLY A DIY WORLD. People built their own aircraft and flew them. Drones’ popularity really exploded with buy-and-fly, out-of-the-box aircraft. A whole generation of photographers and videographers wanted aerial imaging but didn’t want to solder wires together. The DJI Phantom changed things by providing a ready-to-go flying camera platform that was easy to fly.

The leaders in aerial imaging platforms today are DJI, Autel, Skydio, and Freefly. Let’s briefly examine some of the most popular aircraft.

DJI

DJI are currently the world leaders in aerial imaging platforms, and I don’t see that changing any time soon. In fact, it was DJI’s Phantom quadcopter that kick-started this revolution in aerial imaging.

PHANTOM

The Phantom is the original consumer drone that kicked-off the whole thing.

The Phantom was a very capable piece of hardware that was able to get a GoPro camera up in the air. Although other small drones existed before the Phantom, its Naza-M flight controller and its use of satellites for stabilization made the Phantom easy to fly. While this was only in 2013, it seems like a quantum leap in technology. There was no FPV or mobile app for flight. The camera was a GoPro attached to the bottom of the aircraft.

DJI then launched the Zenmuse gimbal, with 2-axis stabilization, which allowed for smoother camera movement without the “Jello” effect—video footage that is wobbly like Jello. The 2-axis gimbal removed the vibrations and also kept the camera level while flying. It revolutionized the industry because people could shoot stable, smooth, usable footage.

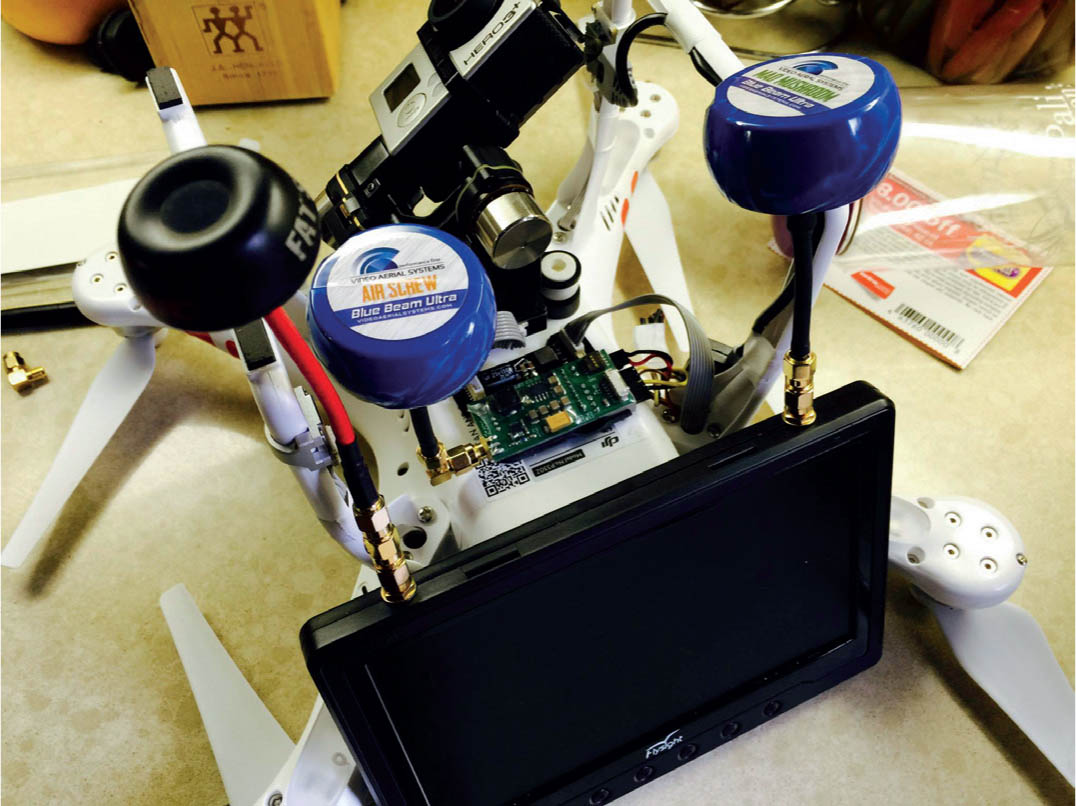

If you wanted to see through the camera, you had to purchase a video transmitter and use it to send the GoPro signal to a monitor on the ground. There was no control over the camera settings. For video or photos you would have to manually start the camera on the ground and then fly with the video running all the time or with the camera in time-lapse mode, constantly taking pictures. If you wanted to know information like height and speed, then you needed to install an iOSD, which would stream back the flight telemetry. I do not miss those days.

PHANTOM 2

Along came the Phantom 2, with more powerful motors and a battery that didn’t require attaching cables and then stuffing them in the door.

One of its options was flying a GoPro with the option of a 3-axis gimbal. The third axis was rotation, which was the missing piece for super-stable footage. If you wanted FPV, you still needed to bust out the soldering iron and do some DIY hacking.

At the same time, DJI introduced the Phantom 2 Vision. I was fortunate to be one of the first to use this craft. I actually owned a pre-production unit. What made this revolutionary was the built-in FPV via the DJI Vision app. This enabled you to see what the camera was seeing through your mobile phone. You could also control camera functions through the app—there was an option to tilt the camera by using the accelerometer on your phone. Because there was no gimbal on this aircraft, you could take photographs, but video wasn’t stable enough to be usable.

2.1 Phantom 1 with prop guards attached and a Zenmuse H3-2D gimbal

2.2 Phantom 2 with homemade modifications for FPV

2.3 Phantom 2 Vision

2.4 Phantom 2 Vision+

The Phantom 2 Vision+ was the first aircraft that had it all. It had the Vision+ camera with a built-in 3-axis gimbal and an updated app for more control and better FPV. The quality of the camera was just OK, and it took a lot of postproduction work to make things look good. Still, we were able to coax some decent images and video out of it.

PHANTOM 3

The Phantom 3 was a coming-of-age product for DJI. It allowed us to easily create professional-looking photos and video. Flight control was vastly improved, with more power. This product was presented in a very slick and streamlined way. The controller was completely redesigned, with separate controls for camera movement, shutter, and exposure. There were two models: the Phantom 3 Advanced and the Phantom 3 Professional. The big difference was that the Pro could shoot 4K video, and the Advanced could shoot up to 2.7K (after a firmware update).

2.5 Phantom 3 Professional

A major leap forward was the inclusion of Lightbridge, an HD-quality FPV with a very long range. Lightbridge was originally available as a separate accessory for the larger spreading wings series and was only introduced as an included feature on the Inspire 1. It allows an HD signal to be displayed on your screen with almost no delay and a crystal clear image. Lightbridge works over RF, so there is no need for the additional Wi-Fi unit that powers the older FPV system in the original Vision camera. At this point, DJI migrated everything to the Go app, which connected the DJI product line. The Phantom 3 also sports downward-facing sensors to provide optical flow in the same way as the Inspire 1. See the description of the Inspire 1 for more on optical flow.

After a firmware update, DJI added the intelligent flight modes to the Phantom 3 range. The intelligent flight modes enable the Phantom 3 to fly itself.

PHANTOM 4

Less than a year after the Phantom 3, DJI released the Phantom 4. The main additions to the Phantom 4 were more powerful motors, snap-on propellers, composite-integrated camera, and a more streamlined shell with a higher center of gravity for better balance. Sport mode was first introduced with an official 47mph speed.

Perhaps the biggest addition to the Phantom 4 was the forward-facing sensors. This enables object recognition. By detecting objects and identifying them as a person, a car, etc., the Phantom 4 can follow an object as it moves. This is called Active Track and it’s great for people trying to track an object—even themselves. A good practice is to lock onto the target and then fly around it to increase the recognition accuracy. Weaknesses in tracking happen when moving directly into the sun, where contrast is lowered, and when making sharp turns.

Another use for the forward-facing sensors is object avoidance. The sensors can detect an obstacle such as a wall, a tree, or, hopefully, a person. Settings can include stopping, flying over or around an obstacle, and even reversing direction if the obstacle is moving.

More sensors were added to the underneath portion of the aircraft to assist in obstacle avoidance and to increase the optical flow to 30 feet, from the previous 10 feet.

2.6 Phantom 4

INSPIRE 1

On November 12, 2014, I was invited, along with a small group of key influencers, to an event at Treasure Island in San Francisco. All we knew was that DJI was unveiling a new product. During the speeches, the very first Inspire 1 to be seen outside DJI flew into the event space. There were gasps from the attendees, who’d never seen anything like it.

Understand that this was before the Phantom 3, and it was the first streamlined prosumer drone to be unveiled. The first thing that struck everyone was its futuristic appearance and powerful-sounding motors. Also, it was streaming live HD video from its camera onto a large screen. The Inspire 1 was the first small drone to incorporate all of DJI’s separate technologies into a single aircraft, and quite frankly, it was years ahead of its time. A larger and heavier aircraft than the Phantoms, this thing is jammed with tech. First of all, the legs were manufactured out of carbon fiber to make them light and strong. From the downward landing position they can be raised upward into flight position, lifting themselves and the propellers out of view of the camera.

The camera itself was a detachable gimbal. The camera could be swapped out with compatible cameras at the turn of a lever. This camera is capable of rotating 360 degrees and can be remotely controlled by the pilot. Additionally, a second controller can be used by a second operator for complete remote control of the camera while the first operator retains control of the aircraft. The camera is capable of 4K video and 12 MP stills in Adobe DNG Raw.

The Inspire 1 uses Lightbridge for long-range HD FPV with almost zero latency (the delay from camera to screen).

2.7 Launch event at Treasure Island

2.8 Inspire 1

Several additional cameras have been released for the Inspire 1. The X5 camera is a micro 4/3 with interchangeable lenses and adjustable aperture and focus (i.e., a “real” camera). The X5R is similar to the X5, but it records images and video on an onboard SSD drive. The X5R also records lossless video as a series of RAW still images.

2.9 Zenmuse X5 camera

The Inspire is also available with the X5 camera standard. This is known as the Inspire Pro. Once you have upgraded your Inspire, it’s very similar to a Pro and it can run the Pro firmware. The Pro does get a little more battery life than the upgraded Inspire 1 because of slightly more efficient motors.

INSPIRE 2

In 2016, the Inspire 2 saw some significant upgrades, including a magnesium alloy body and a second camera for FPV. This allows the pilot to see where the drone is going while a second operator can control the main camera. Speaking of the main camera, it now has the X7, which features 6K video in Cinema DNG or 5.2K in Apple Pro Res. It’s capable of 24MP stills and has 14 stops of dynamic range. Forward, downward, and upward sensors are included for tracking and obstacle avoidance. Upgraded Lightbridge increases video transmission range to 4.3 miles. The speed is increased to 58 mph.

Mavic Foldable Drones

In 2016, there was big jump forward in design. DJI released the first of the Mavic series of drones with the original Mavic Pro. The major move forward was portability with a foldable design. They also redesigned the controller to be much smaller and resemble a controller from an Xbox or Playstation. The range was expanded to 4.3 miles.

As this point in time, 3-axis stabilized gimbals and obstacle-avoiding sensors with the ability to do live tracking are standard equipment.

The video transmission has been upgraded to the Occusyc system, which sends a clearer signal farther and with almost no latency.

Today, the Mavic-style design is the most common type of consumer drone and is broken into three main families of drones. The name Mavic is now used on the flagship pro line. The Mini is the smallest, and in between sits the Air family.

2.10 Mavic 2 Pro and Mavic 3 drones

Mavic (Formally Mavic Pro)

The Mavic Pro is the drone that changed it all. If the Phantom introduced drones to the masses, the Mavic introduced the masses to drones. With the smaller, foldable design it’s now possible to put a drone into your existing camera bag. At this point, sensors, obstacle avoidance, and autonomous flight and shooting modes have matured to a point where anyone can fly a drone and get half decent shots without any previous experience (Figure 2.11).

ORIGINAL MAVIC PRO

At the release of the original Mavic Pro, you made a choice between quality and size. If quality of shots was important from a smaller drone, then the Phantom was the choice. If you were willing to sacrifice a little quality for convenience, then the Mavic was the way to go.

2.11

In 2015, DJI Acquired a portion of legendary Swedish camera maker Hasselblad, and in 2017 it acquired the majority of their shares. The Mavic 2 Pro was released and was the first drone to feature a Hasselblad camera onboard. This was also when the camera quality on the Mavic surpassed that of the Phantom 4 Pro.

The Mavic 2 Pro sported a large 1” sensor at 20MP. What really set this camera apart was the quality of the color. In my opinion, the quality was head and shoulders above any other built-in camera that DJI had produced at that point.

The Mavic 2 shipped in two flavors, the Pro and the Zoom—the former having the Hasselblad camera, while the latter is using a 12 megapixel camera with a 24-48 mm optical zoom.

2.12

The aircraft itself had also undergone major improvements in speed (72 kph), with a range of up to 8 km and a 30-minute battery life. Other features such as downward landing lights and dual IMU’s helped with safety.

At the time of this writing, the latest in the Mavic Pro line is the Mavic 3, which features a micro 4/3 sensor in the newest Hasselblad camera. The resolution is still 20MP for stills, but the low-light performance is vastly improved thanks to the larger sensor. Video now supports the holy grail of 120 fps in 4K and 200 Mbps, and goes up to 5.1K at 50 fps. The Mavic 3 shoots in 10-bit Dlog. The Cine model even supports Apple ProRes 422 HQ and writes to its built-in 1 TB SSD drive. The difference between the Mavic 3 and the Mavic 3 Cine is the built-in SSD dive to support the higher transfer rate of ProRes.

MAVIC 3 CAMERAS

With the Mavic 3 (Pro no longer used in the name) you don’t have to choose between the Pro and the Zoom camera, you get both. With dual cameras, you get the Hasselblad CMOS sensor as well as a second tele camera (162 mm equivalent) that is mounted right above the main camera (Figure 2.12). The tele works in explore mode and is a 28X hybrid zoom 162mm f/4.4 camera. This is designed mostly for scouting shots without having to fly as far, as well as the ability to film subjects like wildlife without startling them. The format of the zoom produces decent images at native resolutions, but fully zoomed in is better for scouting than shooting (Figures 2.13A-2.13C).

2.13A Zoomed out

2.13B

2.13C Zoomed in

As far as the aircraft, it now supports full 360 degrees of obstacle avoidance with forward, rear, upward, downward, and lateral sensors. The sensors feature omnidirectional, binocular vision system, which is able to see in every direction in 3D, thus giving it a sense of depth. It also has an infrared sensor on the bottom, which is useful flying in low light and indoors. The forward sensors have an impressive 200-meter range for smart return to home. It uses APAS 5.0, which is DJIs latest object detection and avoidance system.

The transmission supports Occusync 3.0, which allows video transmission range at 1080P at 60 fps with very low latency (delay).

The battery life has been extended to a 46-minute flight time (in perfect conditions and no wind).

MINI

The Mini is the smallest of the line and weighs just 249 grams. The reason for the weight is to exempt it from certain regulations in some countries. You don’t have to currently register a drone lighter than 250 grams in the United States. But keep an eye on regulations, as they are changing all the time.

2.14 The Mini 2 is small

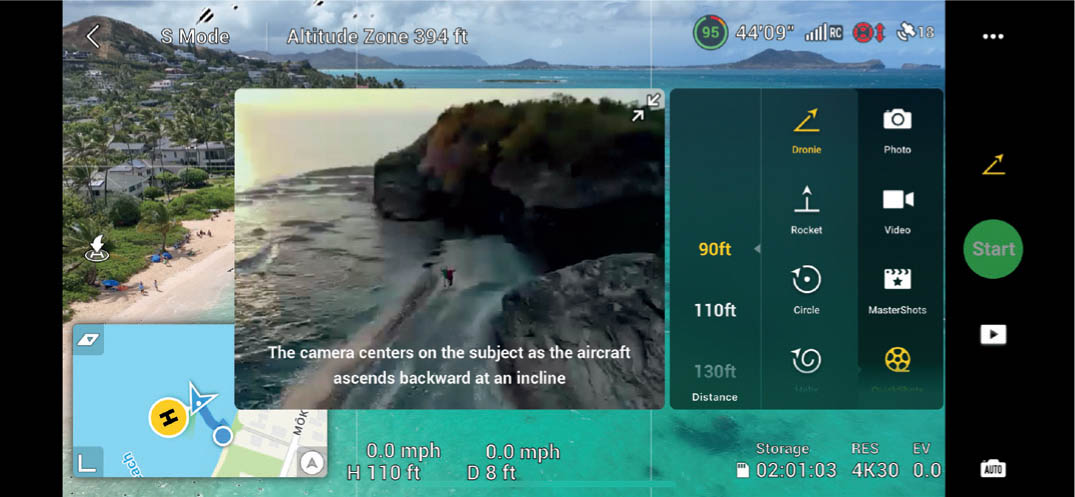

2.15 QuickShots in the DJI app

The Mini is a great option when portability is key. While the camera isn’t as good as the more expensive models, it’s no slouch either. It has the ability to shoot 4K video at 60 fps and the Mini 3 has a 48MP camera.

The Mini 3 Pro brings back the rotating camera. The original Mavic Pro featured a rotating sensor for vertical shooting, but this was dropped in the 2. The Mini 3 has a rotating camera gimble that once again allows the popular vertical shooting. This is an important feature for the target user, who is probably very active on social media (which favors vertical photos and videos on platforms like Instagram and Tik Tok). Another nice feature is the camera is positioned forward and away from the propellers and is able to shoot upward without getting props in the shot. This opens a whole new world of creative possibilities.

2.16 Mini 3 Pro

The Mini 3 has forward, backward, and downward-facing binocular sensors. As well as safety, this also allows the addition of QuickShots and automatic panorama shooting. QuickShots flies the Mini in a series of pre-programmed maneuvers, making it easy to make a highlight reel. The different shots can also be called up a la carte.

The batteries usually add the most weight to a drone. Because of this DJI offers the standard battery, which keeps the drone under 250 grams so it doesn’t need registration. They also offer a larger battery that increases flight time but takes the total weight over 250 grams. For people who already are registered, this is a great option.

AIR

The Mavic Air is the in-between consumer drone. It’s designed to be portable, affordable, and support better image quality than the Mini. Currently in its 3rd edition, the Air 2S offers the best quality images for the price. Video transmission is 12 km and it can fly for 30 minutes (according to specs).

With the Mavic Air 2S you get a 1” sensor on the camera and some impressive image quality for the size. Four-directional obstacle avoidance—forward, backward, up, and down—allows for great obstacle avoidance as well as tracking. It’s easy to track in three ways.

- Spotlight: You fly manually, and the camera stays locked on the subject.

- Point of Interest: The drone circles an object and keeps it in the center of the frame, even when the object is moving.

- Active Track: This is fully autonomous flying and camera control. The drone will follow the subject. It doesn’t have to follow from behind either, it can fly beside or in front of the object.

2.17 DJI Air 2S

Occusync

The Occusync video transmission system has now displaced the Lightbridge system on DJI aircraft. Occusync offers improved range, clarity, and frame rate while reducing latency (the time it takes the signal to update on the screen from the camera). The video transmission is what you see on your controller, goggles, or mobile device. Another advantage of Occusync is the ability to transmit to multiple devices simultaneously. This is important for multiple controllers and the use of goggles by more than one person at a time.

At this time they are up to Occusync 3, and it is only going to continue improving. The important thing is that clear, HD-quality transmission is now mainstream.

Autel Robotics

Autel are well known in the automotive space. They manufacture intelligent diagnostics and testing products and services. They have been focusing on drone technology and seem to be a viable competitor to DJI. Autel are also based in China, with some manufacturing and operations in the USA. The EVO II drones are made in the USA. This enables use by U.S. government and enterprise.

There are currently three models of quadcopters produced by Autel: Evo Nano, Evo Lite, and Evo II.

EVO NANO

The Evo Nano series is lightweight, weighing 249g (under the weight for FAA licensing requirements). This is a direct competitor to the DJI Mavic Mini series and bears more than a passing resemblance to it.

It has forward, backward, and downward binocular sensors, known as a Perception system. These can be used for object tracking and obstacle avoidance.

The camera is on a 3-axis gimbal and shoots at 48MP on a ½” CMOS sensor and can shoot in RAW and JPEG. Video is up to 4K at 30 fps and HD at 60 fps. The maximum bitrate is 100 Mbps. There is also a Nano+ that boosts the camera to 50MP on a 1/1.28” sensor and offers additional shooting modes. The transmission range is 10 km through Autel Skylink and it has a 28-minute flight time.

EVO LITE

The Evo Lite is larger than the Nano and offers 50MP photos and 4K HDR video on a 4-axis gimbal (allowing for vertical video). The Evo Lite+ has a larger 1” sensor and claims best of class low-light performance from the 20MP camera. (I have not personally tested this.) The Lite+ offers 6K video at 30 fps.

This drone has a 40-minute flight time and a range of 7.4 miles.

EVO II

The Evo II and Evo II Pro are the largest of the consumer drone Evo series.

The Evo II shoots a massive 8K video on a ½” CMOS 48MP Sony sensor. It has 360-degree obstacle avoidance and tracking through 12 visual sensors. The flight time is 40 minutes and it has a 5.5-mile range.

The Evo II Pro is the same aircraft with an upgraded camera to offer Autel’s highest image quality. It shoots 20MP stills and 6K video on a Sony 1” sensor. It can also shoot 4K video at 60 fps and HD (and 2.7K) at 120 fps. Bitrate is 120Mbps.

Autel also offers the Evo II Enterprise, which has accessories such as a speaker, lighting system, and thermal camera. Since we are focusing on photography, we won’t go into the Enterprise systems, including the Dragonfish series.

2.18 Autel Evo II Pro

Sony Airpeak S1

Sony is the first major camera manufacturer to throw its hat in the ring and produce its own drone. The drone itself is moving into the heavy lifter range, weighing almost 7 pounds without a payload. The S1 is capable of carrying a Sony alpha mirrorless camera on the optional Gremsy T3 gimbal. The obvious advantage of this drone is very high-quality photographs and video. It has a top speed of 56 mph and a 1.2-mile range. The Airpeak offers a two-person mode. One person pilots the drone and uses the small built-in camera to navigate, while the second operator works the gimbal and camera.

The disadvantage at this point is a reduced flight time once a payload is attached—from 22 minutes to about 12 minutes. Personally, I hope Sony will design a camera specifically for a drone. There is a lot of unneeded weight carrying a terrestrial camera, from the battery to redundant components such as display, grip, and controls. An ideal aerial camera is nothing more than a lens, sensor, and electronics. You need to get the weight down to maximize flight time.

I think at this time Sony is concentrating on getting the drone just right, and then I suspect they will release more accessories in the future, perhaps an integrated gimbal and camera. With the modular design of the Airpeak S1, this is very possible.

Sony’s ability to quickly innovate and update made them the leader in mirrorless cameras. I will definitely be keeping my eye on Sony to see what they produce in the future. I suspect it could get quite interesting.

2.19

Firmware Updates

No matter what hardware you decide to fly, keep an eye out for firmware updates. These updates fix bugs and add new features to your drone. Usually the app will inform you when new firmware is available. Make sure your batteries are fully charged while running a firmware update, and don’t interrupt the update while it’s in progress. Another suggestion I have is to join some groups on Facebook or Discord and wait for the thumbs-up from the community before performing the update. I usually wait about a week to decide if I will perform the update or skip it based on feedback from the community. If a number of people are having big problems because of the update, I usually wait until things are fixed.

RETURN TO HOME (FAILSAFE)

Most, if not all, modern drones use satellites for positioning. These satellites mark the position of the aircraft. The satellites help the aircraft stay steady by using positioning information that communicates with the motors to make constant micro adjustments. There are four main satellite networks: GPS (USA), Galileo (EU), BeiDou (China) and GLONASS (Russian).

Most drones use one or a combination of these systems. DJI seem to be discontinuing the use of GLONASS and using GPS, Galileo, and BeiDou. One of the important tasks performed by satellites is to mark the homepoint. This homepoint is saved as a failsafe destination. That means that if the controller loses connection with the aircraft because of a malfunction, battery failure, or an accidental drop into the ocean, the aircraft doesn’t just keep on flying away by itself until it crashes into something.

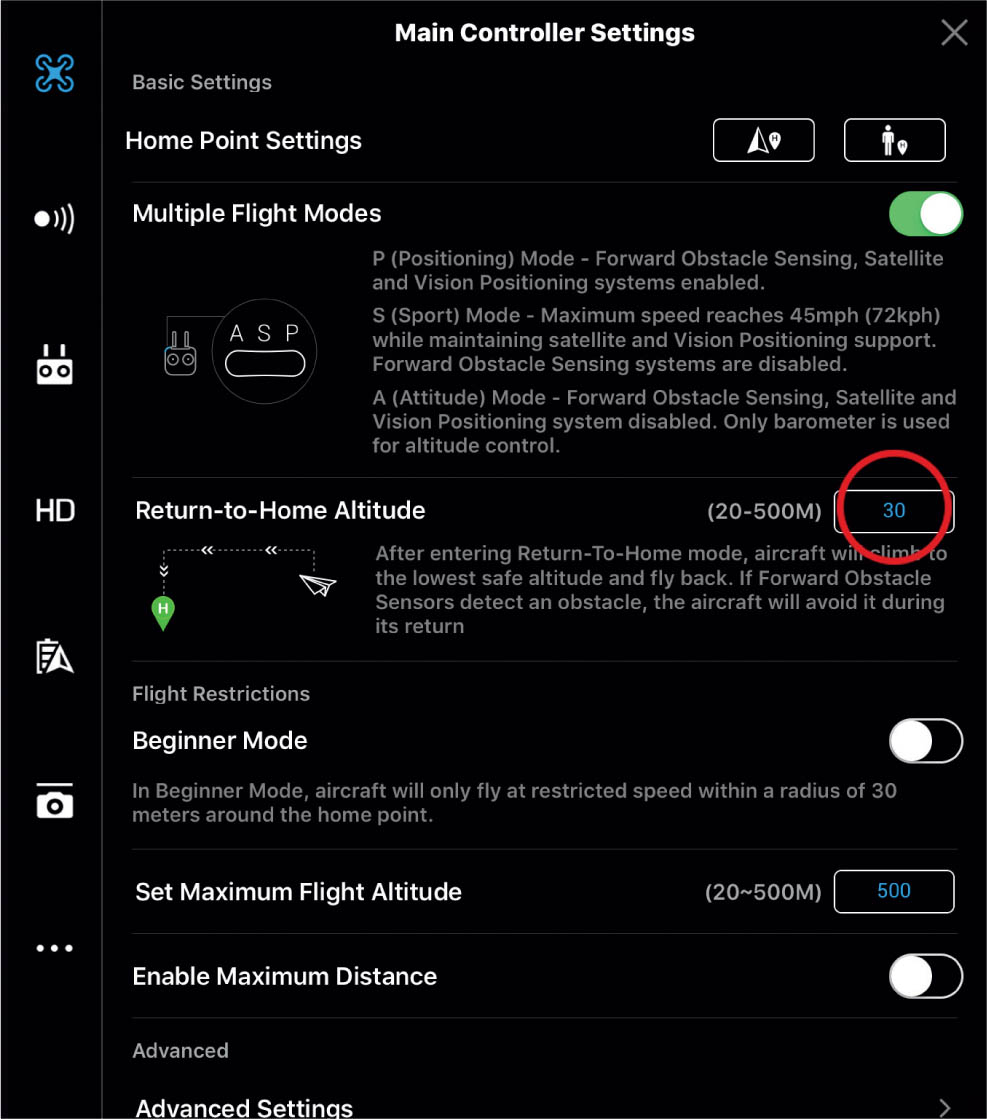

Instead, the aircraft will climb to a safe altitude (this is usually programmable in your app; see the operating instructions for your aircraft) and return to the home position (or homepoint), automatically land, and shut off the motors.

2.20 Homepoint settings

This failsafe is also used in monitoring the onboard batteries on the aircraft. When the batteries get low, the aircraft will return to the homepoint. You have the option to override this if you want to continue flying. However, once the aircraft gets critically low on power, it will go into a self-landing mode. At this point, you still have the option to guide the aircraft to a safe place to land (if you canceled return to home). Once it’s in critical mode (usually at 20% battery), you cannot cancel landing, because the software won’t allow your aircraft to run out of power in midair and fall from the sky. This is a good safety measure.

You can also force a return to home by pressing the Home button on your controller or app. Once again, refer to the instructions for your particular aircraft to familiarize yourself with this feature before your first flight.

STATUS LIGHTS

Under each aircraft, usually at the ends of the arms, you will see status lights that provide important information. These lights tell you when you have satellite lock, when it’s safe for landing, when the batteries are getting low, and if there is an error.

Please refer to the instruction manual to see what the lights mean on your aircraft. Generally speaking, flashing red is never good, amber means that certain features are disabled, and green means all is well. Learn what these lights mean; your aircraft could be trying to tell you something important.

GEAR

Filters

Filters may be some of the most misunderstood accessories for aerial photography and video. Whenever I post an image, I always have people ask if filters were used. This is a fair question, but I have discovered that many people think if you put an ND filter on your camera, suddenly all your photos will be sharper and more vibrant. Many times, these filters produce the opposite result and can make a photo look worse. After you read this section, the purposes and uses of filters will be clearer to you. Then when you do use filters, you will see an improvement in your images.

A filter is a thin piece of glass that screws or snaps onto the front of your lens. Different types of glass have different properties that affect your photographs in different ways. The main thing is that they are distortion free, clean, and, for aerial work, lightweight.

There are several types of filters to discuss: ultraviolet (UV), circular polarizer (CP), neutral density (ND), and graduated neutral density (GND).

ULTRAVIOLET

A UV filter is simply a clear piece of glass that sits on the front of your lens. This filter protects your lens from scratches by taking the beatings for it. Some manufacturers claim that the way the glass is honed gives you sharper images and reduces glare. Some photographers claim that the extra glass on the front creates glare and blur and undermines the benefits. I use them for protection.

2.21 Filters

CIRCULAR POLARIZER

One of the most useful filters for traditional photography is the polarizer. A polarizer creates richer colors while reducing glare and reflections off water and glass. When light bounces off things, it scatters and creates glare. A polarizer filters out all light except the light moving in a certain direction. By rotating the circular polarizer, you can choose which direction of light rays you want to see.

Take two pairs of polarized sunglasses and put them on top of each other. Rotate the top pair to see what I mean—at one point the lens will appear solid black, whiCh is polarization at work.

The advantage of polarizing filters is the ability to rotate the filter to reduce or remove reflections and glare. You will get bluer skies, clearer clouds, and more highly saturated colors in your landscapes. This only works when you are at an angle to the sun, 90 degrees being the most effective. You won’t see much of a difference with the polarizer when looking directly into or away from the sun.

Polarizers do have some challenges and side effects. They will darken the exposure; this may or may not be a benefit, depending on the circumstance.

You obviously can’t rotate the filter while your drone is in the air. That would require a servo on the filter, which I’m sure someone is in the process of building. The rest of us have to rotate the filter while we hold our aircraft or while it’s sitting on a secure base. The added challenge of this is that we have to have a video preview of the effects of the filter as we rotate it to get the benefits of it. This means having the camera on for this process, so we are fighting the active gimbal at the same time. This will get things perfect for a certain shot, but when we rotate for another shot, the filter may not be set up right—we either have to make do or land and adjust the filter.

2.22 Taken on the Phantom 4 without a polarizer

The other issue with a polarizer on a wide lens is that it can’t polarize the entire sensor. This can create a darker area in the middle of the sky, with more white toward the edges (see the sky in Figure 2.23). This makes it a bad choice for shooting panoramas unless you want a leopard-skin sky. However, Photoshop sky replacement can be used to fix it; see more on that in chapter 7.

Because of the challenges and side effects, I don’t use a polarizing filter that often because it’s such a hassle. But for certain shots it’s magical.

2.23 Now using a polarizer—notice the richer color

NEUTRAL DENSITY

If I could only have one filter, it would be the Neutral Density filter. This filter shouldn’t change the quality of light at all; it doesn’t sharpen, color, cut through glare, or any of the mystical things people think it does. All it does is reduce the amount of light entering the lens, making everything darker. Because there is less light entering the lens, you have to slow down the shutter speed to get a correct exposure. You could increase the ISO, but all you would be doing is adding unnecessary noise to your images. Let me explain ND for photography and for video (where you will use it all the time).

2.24

In photography, the shutter speed is the amount of time that the shutter is open to expose the frame. When it’s bright, you want a shorter (faster) shutter speed; otherwise, your image will be overexposed and too bright. When it’s darker, the shutter needs to be open longer (slower shutter speed); otherwise, the photo will be too dark.

With a shutter speed of 1/1000 of a second, movement will be frozen, with no blurring at all. You can see that effect with this image of water spray captured in motion (Figure 2.24).

This second photograph was shot at the much slower 0.6-second exposure. Because the shutter is open longer, more movement happens in that time, and is captured. This creates a flowing motion effect (Figure 2.25).

2.25

The ND filter reduces the amount of light entering the lens, so you can use a slower shutter speed. They come in different densities to allow compensation for different shutter speeds. Higher densities block more light. Unless you want to slow down the motion and create some blur on your photo, you wouldn’t use an ND filter. If your copter is moving, the entire photo could likely be blurry when using an ND. Make sure you are hovering, and let the motion happen against a stationary object. If you want tack-sharp photos, the ND filter will actually give you the opposite result.

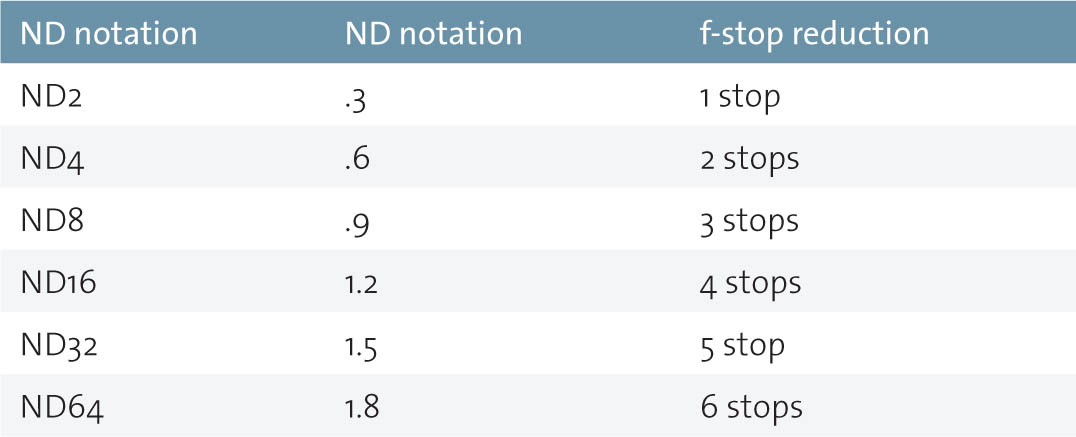

Different manufacturers use different notations to describe their filters. Here is quick chart that shows the notations and how much light they block.

In video, the ND filter is a necessity.

It’s important to use the correct shutter speed for smooth video. While tack-sharp frames are desirable in photography, the opposite is true for video. For fluid movement and motion, a little bit of motion blur makes the video look smoother. If the shutter speed is too fast, the action appears jerky and staccato. Water drops end up looking more like sparks than they do smoothly flowing liquid.

The formula for the best shutter speed for video is 1 over 2x the frame rate. If the frame rate is 30 fps, then 1/60 is ideal. For 60 fps, use 1/120. For 24 fps, use 1/50 (there is no 1/48, so we choose the closest shutter speed available).

To get the correct exposure, often the corresponding shutter speed is much faster than what we want for video, so we need to reduce the amount of light with the ND filter. More quality video is shot with an ND than without. You will use an ND all the time when shooting video outdoors during the day unless it’s heavily overcast. It’s easy enough to tell—just zero out the meter on your camera in the app and see the shutter speed. If it’s too fast, then add an ND.

Typically, you would use an ND16 for most bright-day shooting, or go up to an ND32 when it’s very bright, such as over water or snow. If it’s a bit cloudy, the ND8 might do the trick.

Here are common shutter speeds in full-stop increments: 1/1000th of a second, 1/500, 1/250, 1/125, 1/60, 1/30, 1/15, 1/8, 1/4, 1/2, 1 second.

GRADUATED ND

The last type of filter that we’ll discuss is the GND. This filter is tinted at the top and clear at the bottom. There is a smooth gradient where the darker region blends into clear. This enables us to darken the sky without the foreground being darkened. This is a great option for shooting outdoors and shooting landscapes because the sky is usually brighter than the ground. By adding a GND, we can balance out the difference and show more detail in the sky and the ground simultaneously.

First Person View (FPV)

FPV means seeing what the camera is seeing. Video games like Doom or Call of Duty are called first-person shooter games because they put you in the virtual driver’s seat, as if you were actually there. FPV does the same thing. It’s easier to see where you are flying when you are looking through FPV, because you can see obstacles and clearings in front of you. When the aircraft is a fair distance away, it’s hard to gauge where it is in relation to other objects because of the reduced depth perception.

While FPV is nice to have for flying, it’s really important when it comes to framing your shots. When you are making photographs, use the FPV to frame up your shot. When you are shooting video, you will use it to frame the shot, but also to maintain that frame as you move though the shot.

There are two main types of FPV: screen and goggles.

FPV SCREEN

These days, a screen usually means a phone or tablet, but not always. Many drones, such as the Inspire 1, can have a large monitor plugged in through the HDMI jack. This allows a remote feed of what the camera sees. There are also controllers with the display built-in, such as the Phantom 4, Smart Controller, and RC and RC Pro from DJI. These have the app preinstalled on an android system and feature a 5.5” screen. This is a great way to save batteries on your phone. Also convenient, you don’t have to plug in a phone, launch the app, and turn on the controller—it’s all done with one button.

2.26 DJI Smart Controller and RC Pro

Most commonly used is an iOS or Android mobile app that you download on your smartphone or tablet. These all-in-one apps allow you to change equipment, camera, and telemetry (speed and location) settings, and provide a large real-time display of the camera feed. Most of these apps also include a flight recorder that allows you to access your flight logs at a later date.

For most purposes, I like to fly line of sight and keep an eye on the FPV for reference, because I like to be aware of my surroundings. When doing a video shot, I will be looking mostly at the FPV device to make sure the framing is good and that I like the speed and movement. I will be aware of my surroundings and have a spotter with me who watches the aircraft while I’m not. As soon as I’ve got the shot, I immediately look back at the aircraft and make sure everything is nice and clear.

Sun glare can be an issue, so a sunshield for your screen is important. You can make one yourself out of black foam core. Sunglasses can be worn, but make sure they aren’t polarized, because this makes it difficult to see the screen.

2.27 Remote with iPhone attached

GOGGLES

FPV goggles are a fully immersive way of looking through your FPV. When you wear these goggles, all you see is the display through the eyepieces. It provides a very clear view of the FPV and makes it very easy to see and fly as if you were up there in the drone yourself. Because of this superior view, FPV goggles are used for drone racing.

Because I shoot photos and video, I don’t exclusively use goggles. I like to be aware of my environment and know where the drone is in space at all times. However, you could fly to position, look around, make sure there are no obstacles, and then put on a pair of goggles and fly. Looking through the goggles can help with composition because it’s like seeing your image on a movie screen. Be aware if you are in the USA, law dictates you must have a visual observer standing next to you if you are flying with goggles.

2.28 DJI Googles

My favorite option is to use the Inspire in dual-operator mode. One pilot flies the aircraft using visual line of sight while the second pilot is the camera operator. They don’t have to worry about the aircraft, because they aren’t flying it. They are operating the camera. It’s really nice to be immersed in your own little world as the camera operator and get the best shots possible. The Sony Airpeak also allows this option.

There are goggles that plug into the HDMI slot of your controller, such as the Fat Shark.

DJI also make their own goggles that work wirelessly with their drones through Occusync. These also allow head tracking, which move the camera with your head movements. Check compatibility with your drone before purchasing goggles.

Batteries

Why mention batteries? You charge them; insert them; fly; rinse; and repeat, right? There are actually a few things you should know about batteries for safety and also to make them last longer.

The most common batteries used in UAVs are LiPo batteries. LiPo stands for lithium polymer or lithium ion polymer. The lithium ion isn’t that different from what’s used in the latest laptop computers. The difference is that they are wrapped in a soft polymer pouch. They are multi-cell batteries. LiPos are popular because they have extremely high power, are lightweight, and can be made in almost any shape or size.

2.29 LiPo batteries

It’s recommended to charge these batteries in a well-ventilated, fireproof area, and to not leave them unsupervised while charging. The smart chargers are a lot safer and easier because they shut off once the batteries are charged. Otherwise, the batteries could explode if overcharged, and release gasses and sparks that can catch fire. Just do an online search for exploding LiPo batteries and you will find plenty of results.

If handled properly, these batteries are quite safe and will last a long time. Just don’t puncture them, and it’s not a good idea to leave them lying out in the sun. If the batteries are looking puffy or swollen, carefully dispose of them. Don’t be tempted to grab a sharp object and relieve the swelling, as this will almost certainly lead to them catching on fire.

When you have used a battery, it will feel very warm, even hot, to the touch. Wait until the battery has fully cooled down before charging it; this will make it last much longer. Repeatedly charging a hot battery can ruin it in just a few hours.

When storing a battery for an extended time, don’t leave it fully charged or depleted. About half-charged is good. Find a cool place to store it. DJI is now using smart batteries that self discharge if not used for about 10 days. They will slowly release their charge to about half. The days until discharge can be set in the app. Make sure that each battery is programmed individually by inserting it into your aircraft and then choosing the setting in the app. Finally, power down and the battery will be programmed.

2.30 Go app settings: days till discharge

NOTE A battery that has smart discharged can appear to have more power than it actually does. Don’t be tempted to use it for a quick flight, thinking you have half a battery. Fully charge batteries before use if they been sitting for any period of time.

When traveling with batteries on an aircraft, make sure you carry them on and don’t check them into the cargo hold. They shouldn’t be fully charged, and the terminals should be covered. If the batteries are under 100Wh (all the Phantom and Mavic batteries are), there is no legal limit to how many you can bring with you. If you have larger batteries, such as the larger Inspire batteries (TB48) the limit is two on some airlines, but you can get permission to carry more. If you are looking for permission, don’t ask the people at the airport or the flight crew, because they probably won’t know. I was once thrown off a flight from Las Vegas because I mentioned the batteries to a flight attendant who didn’t understand the rules. She talked to the pilot, who also didn’t know battery rules, and I was declared a “No Fly” and marched off the aircraft. After missing my flight and waiting for over an hour while the operations supervisor talked on the phone to their head office, I finally received an apology.

If you are going to be carrying batteries over 100Wh and need permission, call the airline office before the day you fly and talk to someone who is trained to handle these situations. This will save you a lot of headaches. I also recommend printing out the rules from the FAA (or the authorities in the country where you are traveling). You will not need these if you are able to put your bag in the overhead storage or carry them in a personal bag. However, if you can’t carry your bag on, don’t under any circumstances allow your batteries to be checked in the cargo hold. Remove the batteries from the case, but keep the printout handy. Don’t bring attention to it and you will be fine, but make sure to obey the rules and any crew member instructions.

There are a number of reasons to keep your batteries out of the cargo hold. The first reason is that it’s illegal. (It’s perfectly legal to carry them on your person, though.) A partially charged LiPo battery isn’t going to just explode on its own without a reason—which is why batteries are declared safe in a cabin. See all those laptops? They have similar batteries.

There’s nothing in the cargo hold that will cause your batteries to catch fire or explode. However, if they do catch fire for some reason, they will be quickly noticed and easily extinguished in the main cabin. However, if they are in the cargo hold, no one will notice them smoldering until they ignite. And from what I have read, the chemicals used to extinguish a cargo hold fire are ineffective against a lithium ion fire. This is also why you aren’t allowed to check spare batteries for laptop computers, but you are allowed to carry them.

One last thing about traveling with batteries: When going through airport security, remove all the batteries from your bag and place them in a separate bin for inspection. It’s quite common for the inspectors to dust them down to check for explosive materials, because the x-ray machines can’t see inside the batteries. If you leave them in the bag, they will ask you to remove them and your bags will have to pass through the x-ray a second time, causing a delay for everyone.

All in all, I have traveled with batteries and drones many times and, with the exception of that one flight, never had a problem. Just remember to put batteries in a separate bin when going through security, keep them in a carry-on bag on the aircraft, and all should go well. At this point, TSA are used to drones and batteries and it’s not a big deal. If you are travelling internationally though, it’s a whole different story. Check the drone rules of the country you are going to; some counties don’t allow you to bring drones in. Now, these laws could change, so check the rules of the airline before departure so you know what to expect. Also, do everyone a favor and comply with TSA and crew instructions at all times.

SD Cards and Readers

When you are shooting, you are saving your photos and videos to a memory card. The most common type of memory card used in drones is the microSD card. These tiny little cards are popular because they are small and lightweight and allow the camera to be smaller.

It’s important to get high-quality cards—not just for reliability, but also for speed. You’ll want to use a Class 10 card at the very least. If you want to shoot 4K video, you need a card that is fast enough to write all the data. The other thing to consider is shooting photos. When you shoot a photograph, you want to be able to change settings on your camera and shoot again. On many cameras (all the DJI ones), you cannot change settings, shoot a video, or shoot another photo until the camera has finished processing. You will see a spinning blue circle over the shutter button on the app. The faster the card, the faster the writing process, and the sooner the camera is free again. This is especially noticeable when shooting multiple images in AEB or burst mode.

You really do notice a difference with the faster cards for shooting, as well as for transferring your images to a computer or hard drive after shooting.

To transfer data off the cards, you’ll need a good card reader. Many of the Lexar and Sandisk cards come with either a USB adapter or an SD card enclosure so you can transfer files. If you are using UHS-II cards, make sure your reader is also UHS-II (and your drone supports them) or you won’t get the full speed out of them.

Just a little tip—when you have finished transferring your media after a shoot, don’t just erase the old files off the card. Verify that all the data has successfully transferred. Put them into your camera and format them before use; this will help with reliable writing to the card the next time you use it. Make sure you have a system (such as transferring images immediately after a shoot) so that you don’t accidentally erase the only copy of your photos or videos. That really hurts. When shooting I keep the unused cards label-side up and the used card label side down in my card holder, so I know which cards have data on them.

2.31 Lexar microSD cards

Bags and Cases

The first thing I did when I got my first drone was find a travel case for it. It’s important to have some way to transport it, and the cardboard or foam box it came in won’t cut it for long. There are a few things to look for in a good case. First and foremost, you want it to protect your aircraft, so you want something that fits your aircraft snugly so it can’t move around. You also want a soft support so that your aircraft doesn’t get scratched. Separate compartments are good too, so you can hold all your accessories. You will be carrying your controller, spare batteries, propellers, FPV device, microSD cards, maybe some tools, and possibly a battery charger. I carry a charger or two when traveling out of town, but when I’m local I don’t drag a charger around with me. I usually have four or five batteries, depending on the aircraft, and that’s usually sufficient for most things.

The GPC hard cases (goprofessionalcases.com) are the best I have used and are the most popular today. They are watertight molded plastic. The box is very strong and sturdy, and it has a rubber seal around the opening so it won’t let moisture or dust and sand in. They have nicely designed interiors of custom waterjet-cut foam that fits your gear perfectly. Each component has its own custom-cut space that holds it safe and secure.

GPC also makes backpacks that are filled with the same custom-cut foam. They hold everything from a Phantom to an Inspire. Thinktank Photo also makes a nice backpack called the Helipack.

Usually when I’m hiking, I prefer the backpack. When I’m local or traveling by car or air, I’ll take the hard-shell case. The GPC hard cases also come with optional wheels, of which I’m a big fan, especially for the Inspire, which can get heavy.

2.32 GPC cases