Chapter 1

The Industry

How the Entertainment Industry Functions

This opening chapter beneficially presents a Google satellite view of the entertainment industry’s 10 major participant categories, drilling down into each of their specifics from a producer’s perspective. It also presents the most successful independent production companies as development and production businesses with well-exercised global distribution relationships, some with their own distribution capacities. It further considers dynamic new shifts in branding and distribution and the bold frontier being exercised by entry-level and seasoned producers using these technology-enabled industry upgrades. Finally, and appropriately, it examines story as the unyielding critical core of each successful producer’s universe.

Major participant categories and their functions

There are 10 entertainment industry participant categories, each with its fundamentally crucial and independent functions, each reliant on the others for their survival and all with whom producers have relationships. The most prosperous companies in each category are successful, in large measure, because they sustain a perspective of how the whole industry operates, continually sharpen their individual participation, some of them stabilizing their positions by successfully operating in more than one area.

This perspective includes the view that (1) the entertainment industry is a consumer-product business, (2) each participant contributes to and relies on other participants, and (3) audiences, in their various target definitions, are each project’s most important participants.

In their order of importance, here are the 10 categories of participants:

- Audiences

- Distributors

- Independent Producers

- Retailers and Licensed Media

- International Territories

- Financing Participants

- Distributor Subcontractors

- Production Talent and Subcontractors

- Ancillary Media and Licensees

- Major Consumer Brands

Participant category 1: audiences

Audiences are the highest priority participant category because they provide the income. Without them, there is no industry.

After discovering a story they want to tell, it is highly beneficial for producers to ask two audience questions:

- By order of dominance, who are this project’s unique target audiences? The answer to this question enables a producer to discover the size, entertainment consumption, and media-use profile of each of the project’s target audiences—in the project’s primary global release territory and in each of the project’s other major territories. Together, these are each project’s audience universe. Knowing the sheer size of this audience, their branding triggers, consumption profiles, and lifestyles become core elements used in branding the project, engaging its audiences, planning and forecasting the project’s development, production, and earnings.

- How have these audiences responded to at least five projects released in the prior five years that are most similar to the project being considered? The composite of these becomes this project’s comparable or antecedent model. These projects should be chosen because they are most like (in order of importance) the subject project’s emotional drivers in its anticipated advertising and marketing campaign, as well as its above-the-line talent (director and lead cast), story, and genre. The discovery of these comparable projects provides producers crucial understanding in the branding of the subject project and enables them to most accurately project its gross receipts, the producer’s share of gross receipts, release strategies, brand partners that should be considered, and other valuable information.

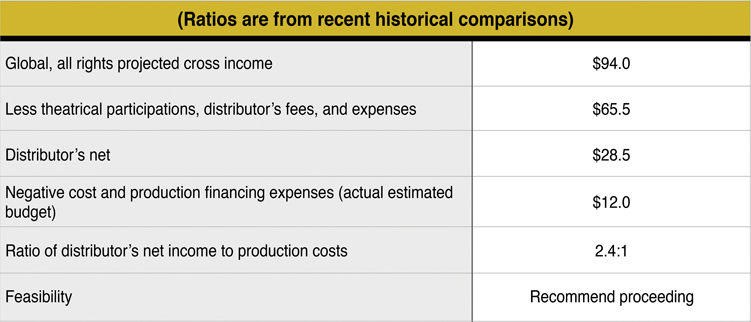

Internal Greenlight Analysis

The answers to these two questions provide a project’s income and distribution cost prospective that, when combined with the project’s estimated production costs, allow producers to determine whether this project has a sufficiently high success probability to proceed with its development. This is a producer’s internal greenlight process.

Producers determine the earnings-to-cost ratio that each of their projects must meet or exceed to be greenlit. It is common among seasoned successful producers to use a two-to-one earnings-to-cost ratio.

For instance, if a project’s audience profiles and project comparables point to earnings high enough to be twice the project’s projected all-in production cost (its earnings-to-cost ratio is two-to-one), this producer would continue with development. If a project’s target audiences lack dynamic consumption profiles or are too small or difficult to reach in comparison to the project’s costs, the producer should pass rather than proceed. The project should only be kept if earnings potentials can be increased, production costs diminished or enough of each to render it feasible.

To be consistently profitable/successful, producers must be as committed to their business criteria as they are to their creative. Both must be satisfied.

The specific methods of obtaining and analyzing this information and a complete explanation of obtaining a project’s internal greenlight are presented in later chapters, especially Chapters 2 and 14. The following diagram demonstrates the fundamental economics of this process.

Figure 1.1 The Project’s Internal Greenlight Analysis (in millions)

Audience Orientation

Producers find it beneficial to understand and use the terms, reports, and culture employed by global advertising agencies and reporting entities in their unique territories, such as Nielsen Media Research, TV By The Numbers, Ad Age, and MPAA in the U.S. Being well exercised in this culture is essential to understanding their reports and is especially beneficial in a producer’s relationships with global distributors, product placement and premium tie-in brand representatives, advertising agencies, public relations and promotion companies.

Audiences in most global territories are categorized demographically by age as follows: kids 5 to 11, youth 12 to 17, and adults 18 to 24, 18 to 34, 25 to 34, 25 to 44, 25 to 54, 45-plus, and 55-plus. Audiences are also identified and evaluated by lifestyles, such as active adults, affluent adults, educated adults, inner-city youth, working women, and so on.

Excellent, easy-to-use audience research analysis tools and databases in the largest global territories (such as Arbitron and Nielsen in the United States; see Chapter 16 for information sources) are available to producers at reasonable costs or are accessible through major advertising agencies and media planning and buying companies. These online audience research tools allow target audiences to be searched, sorted, and identified by an extensive array of demographic and lifestyle search criteria. The lifestyle options are broad, the data are reliable, and the reports are exceptionally useful for audience quantifying and qualifying.

For example, you can sort a given territory’s major metros by women 18 to 34 who are college graduates, watch streamed media at least three hours per week, download music at least once a week, and comment on social media at least three times a week. The requested report can reveal how many are in this audience universe, where their population concentrations are, what are their consumption profiles for the various media, which programs they watch at least once a week, and so on.

Becoming conversant with this information and the sources from which it is derived can be highly beneficial, as the application of this information becomes a powerful tool for producers who will be reviewing and/or originating prospective release strategies, early stage marketing campaigns, media buys, and projecting projects’ earnings.

Figure 1.2 Primary Audience Age Demographic Categories

Distributor-Pitch Preparation

Each distributor relies on its own data, exclusive and open market sources of information, evaluation processes, and experience to determine which projects they will release and how they will do so. Also, though most of the projects they release come from independent producers, these are chiefly from production entities with whom they have long-standing, multi-project relationships and are equity partners in addition to being their distributors for certain global territories and media. Further, they are used to most of the other independent producers who approach them to be capable in pitching the creative tenets of their projects, but being unfamiliar with the mind-bending sophistication of branding and releasing projects in the world’s global territories.

It is important for producers to understand that for projects distributors are interested in, they will perform their own well-honed market analysis. However, they will be both intrigued by and extend a possibly broader, more valuable relationship to producers who can point to their projects’ target audiences, comparable projects, and potential branding partners and strategies.

Pitching projects to distributors, after having first fulfilled their internal greenlights, empowers producers to present the fundamental core information essential for distribution executives to evaluate their interest. This information includes the project’s audiences, recently released comparable projects, and estimated gross receipts in the distributor’s territory. Producers armed with this information are in the strongest position possible to both present and negotiate from the distributors’ perspectives.

Chapter 2 reviews ways to present this information appropriately to receive optimal positive distributor responses.

Participant category 2: distributors

Just as audiences are each project’s primary business consideration, so are distributors each project’s second most important participant, as they are the project’s connection to its audiences.

Each project’s major distributors, marketing and sales companies in its global territories, establish its brand presence to its respective target audiences and to the various media through whom they distribute.

In the United States, the major distributors are 20th Century Fox, NBCUniversal, Disney, Paramount, Sony, Warner Bros., and Lionsgate. Each of these is a full-service studio in the traditional definition, except for Lionsgate, which only lacks a studio lot. These seven majors are global all-rights distributors, able to distribute worldwide to every theatrical, nontheatrical, and ancillary market. And they are the prominent U.S. theatrical, streaming, and home entertainment distributors for major U.S. independent producers.

In addition to the major studios are the following distribution outlets:

1. Independent theatrical distributors.

There are several strong independent theatrical distributors, three of which are owned by major distributors (Sony Pictures Classics, Fox Searchlight, and Focus Features). One of the largest and best-operated of the independents is STX Entertainment. The largest of these are all-rights distributors. A group of new or repositioned veteran distributors are now filling the shoes left by studio divisions chiefly concentrating on wide releases. These include Roadside Attractions, IFC, Magnolia Pictures, the Samuel Goldwyn Company, A24, The Weinstein Company, The Orchard, and Bleecker Street who are especially adept at releasing niche/special-handling titles.

2. Direct international territory distributors.

The largest of these are studios within their respective international territories, which produce and direct-distribute to all the major media in their territories and who also sell their projects’ rights globally. These distributors are presented in Chapter 3.

3. International Sales Agents (ISA).

The largest of these organizations finance and co-produce some of their own projects, in addition to acquiring projects and licensing international rights and distribution services for their independent producers’ projects. These include FilmNation, IM Global, Myriad Pictures, Voltage Pictures, and Highland Film Group.

4. Producers’ representative organizations.

These organizations plan and execute sales to ISAs or distributors in international territories, and they may also plan and engage all U.S. rights sales of their independent producer clients’ projects. Among these are the major agencies including CAA, ICM, WME, and companies such as Cinetic Media and Gillen Group.

5. Television syndication companies.

These companies plan and carry out sales to television stations, cable television networks, and the cable and satellite television systems. Major U.S. television syndication companies, most of whom also do international television syndication, include Warner Bros. Television (WBTV), 20th Television (20TV), ABC Syndication, CBS Television Distribution, Sony Pictures Television, and Lionsgate Home Entertainment.

6. Publishers.

These entities are discussed in more detail in Chapter 5 and primarily include book publishers who are either republishing novels associated with projects being released or publishing new novels based on original screenplays; graphic novels, comic book, coloring book, and workbook publishers who create and release books coordinated with project releases; and paper-based role-playing and other game publishers who create and distribute their respective products timed with project releases.

7. Ancillary rights sales companies.

These organizations, examined in Chapter 5, include companies specializing in merchandising, in-flight, scholastic, ships-at-sea, and other sales and marketing.

Establishing each Project’s Brand and the Studio Operating Perspective

The operations and functions of U.S. theatrical distributors are presented in Chapter 2. The following section merely introduces both the distribution phenomenon of establishing a project’s brand as well as the distributor’s operating perspective.

Brand Presence

In each global territory, every project’s value for its successive available market is primarily established during its premier release. This is where the brand, the audience perspective, and the project’s entertainment value are established.

Audiences typically have a higher presumed brand perspective of projects that have a theatrical premier. As is thoroughly explored in Chapter 2, although theatrical is the most brand high-profile window, media expenses for brand establishment in many global territories are so costly that most projects do not earn sufficient income from their theatrical releases to fully recover their brand-establishing advertising expenses.

The physical aspects of theatrical distribution are highly sophisticated. For some territories, these functions include booking the multiplexes and the screens within them that are best matched with each project, negotiating favorable film rental terms with the circuits, media/advertising creation and buy, staging the physical release of the project through film exchanges, and, finally, the actual settlements that are negotiated with each theater circuit after each project’s play. How well the distributor performs these operations substantially determines each project’s success.

For example, audiences expect the finest projects to be on the largest screens at the best theaters. A good project booked at a questionable multiplex or playing on a smaller screen sends a message to the target audiences that it may be a poor project, potentially overturning other well-executed distribution moves.

As complex and crucial as physical distribution is, however, the peerless genius in the art of distribution lies in establishing the public’s opinion of each project before its release, creating buzz through use of teasers, games, opinion leaders, social media influencers, as well as through paid advertising, ground-swell and spectacle publicity, promotion, and increasingly viral social network marketing campaigns. These are the processes through which projects become must-see major brands to their target audiences.

A brand is the name by which consumers identify a product or group of products. Apple, BMW, Levi Strauss, and Nike have the luxury of fighting for sustained brand dominance. Theirs is a continuing and rugged battle, but it pales in comparison with project entertainment brand establishment.

Every Project Released Is a Separate Brand

Each project must come from absolute obscurity (except for franchises, sequels, pictures based on stellar-successful global games or novels) to become top-of-mind with each project’s target audiences. In most major global territories, strategic marketing planning begins 12 to 24 months before a project opens and is substantially accomplished in a final major media blitz beginning three to six weeks before the project opens, often in concert with other established brands catering to the same target audiences.

In territories that substantially rely upon online and television ad campaigns, such as the United States, the ad buys may have a reach and frequency performance as high as 12 impressions (advertising viewings) by 80 percent of that project’s target audiences before the project opens. In the United States, depending on the target audience and time of year, the cost of media alone for a studio-released project is typically $40 million to $70 million before the project premiers.

Brand presence is so fundamental to a project’s earnings performance in every succeeding distribution category that distributors’ projections of the project’s gross earnings are forecasted as a percentage of each project’s opening weekend theatrical receipts.

Typically, the distributor originates and directs the entire campaign, and it is the campaign, its online events and strategies, media buys, brand tie-ins, and promotions that drive each project’s opening audiences. However, it is social networks’ instant mass-messaging and texting that create waves of wildfire positive endorsements, or deepfreeze warnings to keep away that make and determine each project’s post opening success. Still, the project must be in the marketplace and on the right quantity of screens. It must have a brand made recognizable by a campaign. The producer creates the project that will push massive enabling or quelling audiences. It is the distributor that creates the expectation for each theatrically released picture, places it on the right multiplex screens, and primes this project to be a huge hit. The producer and distributor work together, each project’s audiences providing its earnings life.

Though critical reviews have little opening weekend effect on projects whose primary audiences are kids, youth, and young adults, these audiences’ decisions are the most overwhelmed by texts, social media comments, posted reviews, and other social network interactions by friends, groups, and opinion leaders. The most powerful influence will always be each project’s audience entertainment impact. However, for projects that may elicit either strong positive or negative responses, strategic preparation is wise, doing all possible to amp positive posts.

Producers should carefully consider each project’s uniquely high-impact use of games (especially phone), as well as radio and outdoor advertising as brand-making, audience-driving forces. Examples of this were the pre-premier release of the lead music and soundtrack for the pictures La La Land and Moana. These each impacted brand awareness for opening weekend and substantially fueled audience downloads and music sharing throughout their launch. Outdoor and radio promotions and commercials are especially high-impact during fair weather and school-break periods. For most leading global territories, the two major campaign elements that determine each project’s opening two weeks’ theatrical gross are

- (1) how motivating the internet, mobile, and television commercial spots are to the project’s unique target audiences, and

- (2) the reach and frequency of the campaign’s Internet and television buy/schedule for these target audiences. Mobile, Internet, and television are the hammer media for all audience categories, though clever-audience-hook use of radio, outdoor, and print (Instagram) events and advertising provide powerful audience response.

Producers benefit their projects most when they focus its pre-opening brand establishment. If it is a theatrical release, they do everything possible to assure their campaign creative has deep emotional impact in their targets, and the media planning and buying is dialed in so the aggregate is significantly beyond the critical mass response needed to optimize their audiences, as this will largely determine each project’s opening weekend, and consequently their continuing earnings.

In summary, each project’s premier branding largely determines its earnings capacity in all subsequent distribution release windows. Regardless if a project premieres theatrically, internet streaming (Netflix, Amazon, and Google in most territories), premium cable (in the United States HBO/Cinemax, Showtime/TMC, and Starz/Encore), broadcast network television (in the United States ABC, NBC, CBS, Fox, and CW), cable television (in the United States includes ScyFy, Comedy Central, Lifetime, and so on), as an independent web special or series (especially YouTube and Vimeo), a game (platform on Xbox, PlayStation, Game Cube, or PC single or multi-user games, mobile phone games, and virtual reality), the success of each of these is largely determined by its premier branding. Every production-worthy project deserves sufficient branding to elicit an audience pulse-beat. This is entirely the producer’s responsibility, until a distributor is engaged. Once a distributor is on, it continues to be the producer’s responsibility until the branding has audience-traction.

Distributor’s Theatrical Release Operating Perspective

Each theatrical screen is a unique retail environment. It typically accommodates only one project at a time. Consequently, exhibitors (theater owners) closely examine the earnings performance of each project on each screen. When gross receipts fall below a screen’s house-nut (the exhibitor’s attributed cost to provide and operate that screen), the project is replaced with another. For example, if a U.S. exhibitor has a screen with a weekly house-nut of $3,200 and that week’s gross was $2,800, the distributor knows the exhibitor will soon replace that project with one that has a higher grossing potential.

As discussed earlier, the theatrical revenue that a project earns during its opening week is largely predicated on the effectiveness of its campaign. After the opening week, the dominant social networked audience opinion largely determines a project’s ongoing theatrical life. This being the case, distributors re-create and redefine post-opening campaigns to drive peak audience attendance.

Marketing media from five seconds to three minute teasers, commercials, and trailers, embedded in every form of mobile/tablet/computer communiqués, as well as in paid advertising are the most audience-convincing campaign elements. This is largely because they allow audiences to sample a project’s emotionally tantalizing elements before they invest their time and money, hopes and dreams to experience it. This sampling is sufficiently motivating to initially overpower negative reviews. When viewing the campaign, the audience sees and hears evidence that a project is indeed funny, exciting, romantic, scary, or contains other emotional deliveries that motivate them to see the project or not. When deciding which picture to see, audiences rely more on their own experience, even when that experience is limited to five seconds to three minutes.

Some tech-savvy audience constituents even produce mash-ups (re-edits) of campaigns to show their motion picture enthusiasm or disdain. These are especially powerful because they are from the audience. Distributor-prepared audience pre-and during-release Internet sampling has much more of an impact on audiences than does TV, as it is

- (1) better targeted

- (2) more personal than TV delivered

- (3) significantly less costly

- (4) interactive and

- (5) delivers immediate audience information.

With the power of social endorsement, Internet campaigns are now more influential with all audience profiles. Social networks establish the “buzz,” the “have-to-see,” and peer-to-peer word of mouth both before and after a project premiers. These are and will increasingly continue to be the major audience-drivers, especially for kids, youth, and young adult audiences in most territories.

Every distributor’s first responsibility is to get its project’s target audiences into theaters—or whatever is their project’s premier venue. Campaigns drive audiences; audiences drive each project’s income; each distributor’s prime genius and focus is upon their projects’ premier and after-opening campaigns.

Even in early development, when producers make their earliest project presentations to distributors or sales agents, the most beneficial outcome is achieved by remembering that distributors and sales agents are most interested in the projects salability—the audience’s response to the project’s campaigns. Producer’s achieve their most positive distributor outcome when they help them see, by whatever means, a project’s branding power.

Participant Category 3: Independent Producers

Successful independent producers envision and then produce the most intimate and powerfully impactful stories ever told. Each project released typically first passes through years of screenwriting and other development before it is ready to produce; and then gestates a year or more through its extraordinary production. Whether a project is short or feature length, small or large budget, every project deserves to be worthy of its audiences, have a feasible plan to connect with them, and have a plan that will likely recover the project’s costs and return a profit to the producer and partners, enabling them to continue in their craft and business.

Producers operating in this fashion are Balanced Producers. These are the industry’s leading and most successful producers. They plan and manage all their projects sales and distribution and often directly conduct some sales.

Balanced Producers

An important (hopefully early-career) question for producers to answer is, “Do we solely want to make projects that are the purest expression of our artistic vision? Or do we also want to share our vision of the story with the largest possible audiences and earn a profit?”

Fundamentally, most producers want their projects to fulfill these three major objectives:

2. Audience.

To play my projects to the largest global audiences as possible.

3. Profits.

To recover costs and receive a fair participation from my projects’ earnings.

Balanced producers are simply that. They understand and sustain a balance between their projects’ creative visions, audience, and profits. As of this writing, there exists a small group of balanced producers, operating principally in the major global markets. These include Working Title Films and See-Saw Films in the UK. In the United States, most are in New York or Los Angeles, including Plan B Entertainment, Blumhouse, Chernin Entertainment, and Annapurna Pictures. The projects that come from these producers and their production companies consistently receive global distribution, are profitable, and attain their producers’ creative visions.

Balanced producers understand the essential importance of both preparing their projects for the global marketplace and preparing the global marketplace for their projects. Consequently, their creation and production decisions are based on their initial global distribution responses. It is these relationships that vet their projects’ production financing and assure each project’s maximum earnings in each global territory.

Because of this operating model, most of these producers can use banks to aggregate and provide their production financing, secured by a combination of production incentive (tax credit/rebate) programs, above-the-line or major vendor equity/profit sharing deferment deals, presales, gap funding, and private equity financing. They release their projects through distributors who participate in their valuation and greenlighting analysis, and they extract the maximum possible media and rights earnings from the various global territories.

To become a solid, profitable balanced production entity, producers must employ a regimented, balanced approach to project selection and distribution that leads them to such success. Producers should do the work that engenders the broad global industry relationships that these companies enjoy. Such an operating model is the result of a consistent, balanced approach to the creative development, financing, and distribution of their projects.

These companies’ operating processes naturally mitigate risk, their projects are principally released by major studios (more than 90 percent), their projects are generally profitable (more than 80 percent), and accordingly their organizations build value.

Before committing to a project’s production, in most cases even before acquiring a literary property or idea (except for bidding frenzies, which rarely serve even the winner well), balanced producers proceed only when their research verifies that the producer’s potential gross profits are sufficiently high compared with the project’s approximate production and distribution costs. If these numbers do not proof out, balanced producers have the following decisions to choose from:

- (1) lower the production budget

- (2) increase the project’s earnings power

- (3) pass on the project, or

- (4) know it will be a money-losing project and be sure all investors and production members realize they are doing it for reasons other than profit.

Sometimes referred to as “passion projects,” even creative triumphs can be shallow victories if few people ever see them and they do not earn enough income to cover production and distribution costs.

The Most Successful Producer’s Development and Production Approach

To receive the greatest creative freedom and highest earnings, producers should sustain a balance among each project’s story, audiences (as vetted by a combination of domestic and international territory distributors or agents, preferably during the development phase), and a healthy ratio between the cost of production and the producer’s share of profits (presented in Chapter 2). Successful producers sustain this core business balance.

Just as these producers’ project production analyses include script breakdowns, production boards, schedules, and budgets, so do they include financial projections, global rights sales analysis, distribution window and ancillary products and license schedules, potential premium tie-in lists, and marketing recommendations for and eventually from sales agents or directly from distributors in the major international territories. These processes are more fully presented in subsequent chapters.

For example, understanding the intricate business of project rights sales allows producers to plan, oversee, and even perform some of the distribution of their projects with the same predictability as they manage these projects’ production. Just as there is only one opportunity to produce a project, there is only one opportunity to premier a project, establishing its overall value.

For instance, knowing that a project lends itself to the massive gaming world, toys, novelization, music, and merchandisable products allows a producer, while still in development, the advantage of engaging these formidable relationships as part of the project’s development, as well as including in the project’s production the creation of cover shots to optimize the project’s play in some international versions, in-flight, and television. At the same time, the screenplay’s novelization can be planned and a publishing relationship put in play. Planning the novelization allows sufficient time to publish a paperback to release prior to the project’s release, and feature the project’s one-sheet (poster art) on its covers both online and at retail checkout stands.

Each project’s merchandisable goods can further cross-promote and be released in their optimal timing. Without the producer’s involvement in these processes, the marketing and income benefits are typically lost.

Independent production is inherently intense. Yet, producers embracing these additional practices draw in each project’s greatest possible:

The extra work these require during development is always more than offset by their powerful marketing and income benefits, infusing each project with the greatest possible stability and sanity.

Producers should not expect their distributors to plan and prepare as early or as comprehensively as they will. If the producer is the project’s parent, consider the distributors as aunts and uncles. Although a crucial part of the family, they will never care for the project like the producer will.

Before a producer commits to a project, they should process it through their own in-house tests, as presented in later chapters and summarily in Chapter 14. After a producer internally greenlights a project, then it is time to bring in the rest of the family.

To sustain sanity and balance in their companies and careers, independent producers should establish and follow these basic creative and business processes to experience the artistic, operational, and compensatory benefits. When producers (the third-tier participants) develop, produce, and distribute their projects, deeply meshed with their audiences and distributors (the first-and-second-tier participants), all other industry participants (tiers 4 through 10), will respect and confidently participate with them.

Participant Category 4: Retailers and Licensed Media

These participants are:

- (1) theater circuits (exhibitors)

- (2) home entertainment sales and rentals through kiosks, retail and online stores, and downloading

- (3) VOD (Video on Demand), OTT (Over The Top), and SVOD (Subscription Video on Demand) to all screens

- (4) television premium cable networks

- (5) free broadcast/cable television networks, and

- (6) free television syndication participants, including cable networks, independent television stations and systems.

The producer’s relationships with each of these are presented in subsequent chapters. This section focuses on the larger view of how these retailers impact and contribute to each project’s income and cooperate together in the entertainment arena.

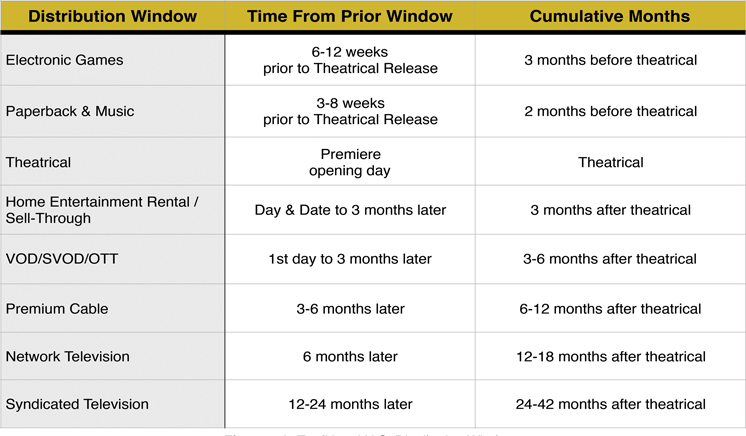

Figure 1.3 Traditional U.S. Distribution Windows

It is important to realize that each of these represents a major, sophisticated, and separate industry. Each has separate associations and conventions, and each makes its own crucial and specialized contributions in selling to its specific and unique audiences.

They are similar, however, in that they all rely on producers to deliver dynamically entertaining projects and for each project’s premier distributor to establish its powerfully audience-motivating brand.

Distribution Windows

Although each project’s release schedule is singular to its audiences, marketing power, premier date, financing, and distribution agreements, the typical U.S. distribution windows for a theatrically premiered project are as follows:

In addition to the substantial and sophisticated campaigns mounted by theatrical distributors, each of these participants makes the following branding contributions:

- 1. Theatrical exhibitors (theater chains) plan and purchase print (newspaper) advertising in their theaters’ markets. Most exhibitors have their own in-house ad agencies that manage this process. They also show in their theaters and stream on their websites: teasers (provocative, high-emotion-impact movie peeks, ten to thirty seconds) and trailers (movie inciting incident set-ups one to three minutes) of coming releases, movie times, maps, and links to purchase tickets. Also, in their lobbies they display one-sheets (movie posters) and standees of current and coming projects. Unquestionably, the most motivating contribution that exhibitors make to each project’s success is providing a high-profile exhibition environment with large screens, superior sound, comfortable seating, and friendly, project-informed staff.

- 2. For theatrically released projects, the home entertainment sector’s hefty-earnings relies primarily on audience demand that was established for each project during its theatrical release. For U.S. theatrically released projects, because most of these projects’ theatrical income is insufficient to recover their distribution costs, most of their theatrical distributors are also their home entertainment distributor. This allows these distributors to have offsetting earnings from both major and overlapping windows and to seamlessly manage and advance each project’s branding for BOTH distribution sectors. For most projects, these distributors also provide additional Internet, television, and other media advertising and promotion, but much less than during their theatrical release. Following screening motion projects theatrically, the unquestioned preference by audiences worldwide is to stream their entertainment to whatever device they prefer at the consumption moment. In most Asian and European territories, streaming to their screen of choice has almost completely eclipsed every other access means. The U.S. still has some DVD and Blu-ray sales and delivery, but these are and will continue to diminish in favor of streaming for one-time viewing and cloud storage for owning.

- 3. VOD (Video On Demand) / SVOD (Subscription Video On Demand) / AVOD (Advertising Video On Demand) / PVOD (Push Video On Demand) are each strong-growth sectors, as they each provide a form of Video On Demand. This common attribute has captured the attention and increasing use of all target audiences. Each of them want each project in its fully robust access, on all screens and transacted by pay-per-view, monthly subscription, or audience-profiled advertising. This is where the entertainment is moving, until it has all moved there. Audiences in every territory are demanding it.

- 4. Premium cable networks (in the United States Home Box Office Inc.: HBO and Cinemax; Showtime Networks: Showtime, Flix, The Movie Channel; Starz Inc.: Starz, Starz Encore, MoviePlex; Studio 3 Partners: Epix) are uniquely important licensees because producers can more easily license directly with them. Audiences continue to subscribe to them because there are few of them and in their aggregate, they provide entertainment in which each target audience has an overall interest. Each premium network uses the brand power of the most popular projects they release to expand their subscriber base primarily by advertising on their channels, the cable systems, and the Internet. Although premium cable in most major global territories continues to grow its subscribers, in the U.S. growth is stagnant, with about half of TV households subscribing to at least one premium cable network.

- 5. Free television cable networks are also easier for producers to license directly. Consequently, the television network premiere often attracts the largest single viewing audience during a project’s life. Television networks are masters at drawing mass audiences by using their networks as the primary source to advertise their free (sponsored) airings of theatrically released projects.

- 6. Free television syndication participants, including cable networks and independent stations, deliver long-term audiences and income. Licensing to these participants is sophisticated, complex, and typically sold and managed by a television syndication company managing extensive content libraries. These stations and station groups, like the networks, primarily advertise projects via their stations.

Participant Category 5: International Territories

These participants include the audiences, distributors, retail media, and other rights purchasers in territories outside each project’s core distribution territory. International territories yield from about 60 percent to 70 percent of the earnings of most projects created by U.S.-based producers, largely depending on the story’s cultural adaptability and above-the-line talent. The leading international territories and producers’ relationships with them are reviewed in Chapters 3 and 14.

Participant Category 6: Financing Participants

These participants often include banks and venture capital funds, which act as financing aggregators and managers that are also collateral lenders, their financing guaranteed by collateral, such as production incentive programs, distribution contracts, presale contracts, or sales estimates of the value of specific territories.

Some countries provide up to all the needed production budget to producers who are citizens of their country and whose projects conform to all that nation’s requirements. Most territories now have multiple forms of crowd funding (donation-based) and crowd financing (equity-based) that can provide some or all of a production’s budget.

Other participants also include:

- Studios and distributors that act as co-financing/co-producing partners for many independent producers.

- Governments, including countries, provinces, states, and cities, provide a single to mid-double-digit percentage of a project’s total financing through production tax or cash rebate programs.

- Further, private and institutional investors may provide development, distribution, and, in some cases, partial production equity funding, some motivated by tax-sheltered programs.

- Also, ancillary partners may provide cash, collateral, and/or co-branding—especially game entities whose game rights may earn higher and longer term income than the project.

- Additionally, production service providers may invest or defer some or all of their fee in the project—such as postproduction, CGI houses, law firms, private attorneys, accounting firms and accountants, who may take the lead in rights sales, talent attachments, and advise, author, and assist in the management of securities.

The roles of these participants are more fully explained in Chapters 2, 6, 11, 12, and 14.

Participant Category 7: Distribution Subcontractors

This category includes sales and licensing specialists, media planning and buying companies, campaign creators and producers, as well as advertising agencies (some of which contribute to all three of the just-listed items). Distribution subcontractors are discussed in Chapters 5, 14, and 15.

Participant Category 8: Production Talent and Subcontractors

These participants include a diverse array of above-and below-the-line performers and crewmembers, imaginers, producers, and suppliers. Especially included in this category are writers, directors, actors, and their agencies, agents, managers, and the attorneys who represent them. Producer relationships with participants in this category are reviewed in Chapters 10, 13, and 14.

Participant Category 9: Ancillary Media and Licensees

This category includes licensed rights, such as electronic games (occasionally out-earning traditional motion picture income), publishing, printing, merchandising, sound tracks/music publishing, and clothing.

This category also includes additional project licensing income from hotels and motels, in-flight and ships-at-sea, and other licensed free audiences, including prison systems, Indian reservations, and schools. Though these may seem small, their aggregate often delivers significant producer’s income share, rendering each worthy of their individual earnings inclusion. These participants are reviewed in Chapter 5.

Participant Category 10: Major Consumer Brands

These participants are brands that link their products or name to a project and advance that project and their own brand through exercising the relationship, especially during its premier. Consumer brand relationships may take a number of forms, but generally fall into two categories. The first and most common is the brand exposure of products used in the project. For this type, the brand either pays for the exposure or gives or lends its products to the producer. The second relationship is a brand’s use of a project to advertise or promote its name or products. Cars, phones, computers, delivery services, fast-food chains, beverages, packaged goods, and fashion brands are the most active participants in these relationships. Sometimes these relationships substantially contribute to the success and increase the income of their projects by escalating their advertising campaigns during theatrical release.

These complementary brand relationships lend authenticity to projects by using brands that create a sense of reality to audiences. These relationships often offset production costs and may even become a revenue source or powerful advertising alliance for the producer. Consumer brand relationships are reviewed in greater depth in Chapter 5.

Participant Category Summary

It can be beneficial to review these motion project industry participants, reconsidering their value order:

- Audiences

- Distributors

- Producers

- Retailers and licensed media

- International territories

- Financing participants

- Distribution subcontractors

- Production talent and subcontractors

- Ancillary media and licensees

- Major consumer brands

Although traditionally viewed primarily as creatives, independent producers who operate their own development and production companies are also business owners. In large measure, their creative and financial success relies on their understanding of, empathy for, and relationships with the industry participants above them on this hierarchical scale (audiences and distributors), as well as with those below them.

Story

If the creative categories were listed in priority, as the business categories have been, one creative category would clearly stand above the others. This is the ultimate art of creative genius. It is where the project is first produced. It is the screenplay.

Story is the most essential and important, and therefore the most powerful creative asset in the entertainment industry. It is more powerful than money. Too many people with deep pockets have entered this industry to establish a production empire, only to leave months or, in some insufferable cases, years later, with a monument of odd and underperforming projects to show for their substantial investments.

Story is even more important than star power or a great director. Even A-list actors and directors, for money or career politics, occasionally allow themselves to be attached to projects that should never have been made. Fine direction and acting may lift a project somewhat but ultimately can never fully redeem a weak story.

An audience-pleasing, entertaining story is the most powerful and essential asset in the entertainment business. Talent with story sense always gravitate to these projects and want to participate in their creation. Business operating technique, organization, planning, excellent relationships with studios and great artists, or the availability of any other assets will never offset the essential need for producers to discover, develop, and produce stories that deserve to be told. The greatest independent producers recognize the uniquely superlative power of great stories.

Excellence in all other producer characteristics will not compensate for failure in this one. Call it story sense, having a nose for the audience, or what you may, this is the single essential attribute, if all the other producer qualities are to even matter.

At the same time, to sustain the whole perspective, it’s important to remember that a great story alone is not sufficient justification for a producer to greenlight its production. Great stories without sufficient audience power as compared to their production and distribution costs should not be made—unless they are produced for reasons other than profit and all the major finance and production participants are fully aware of the alternative purposes.

Great stories are always the germ, the genesis, the foundation of every consummate project. If the story isn’t worth being told, then none of the producer’s other considerations matter.

Chapter Postscript

One of the oldest business adages is, “Nothing happens until somebody sells something.” This is especially true in entertainment, regardless where a project premiers. Each project’s branding during its premier marketing and distribution is the single largest determinate of each project’s success or failure. Fortunately for producers and audiences, the distance between them is shrinking. Though social media is as sophisticated as the technology that delivers it, and is unstable as water, producers can and are having a powerful, positive influence on some of their projects’ branding through use of social media.

Producer’s project branding is not the same as project distribution, and distribution is also where the greatest profits are earned. Consequently, the most successful producers do the following:

- Have strategic relationships with global distributors.

- Set up each project’s distribution and explore each project’s branding possibilities in advance of its production, confirming the project’s basic global earnings value and assuring its most predictably powerful release.

- Are very involved in the initial brand establishment strategy, as well as the release and marketing of their projects.

- Retain some sales and distribution rights in each project.

- Either make or participate in these sales.

The entertainment industry is expansive, robust, and intense. Success largely relies on well-served strategic business relationships with leading entities in every major category. The most successful producers sustain a balance between creative, audience, and profits. This core focus dominates all relationships and decisions, guiding their projects to ultimate and consistent successes.