In this chapter, we’ll be discussing the preparation phase of the Resilience Continuum™ and its four components: prognostication and creating choices, building grit, creating a mindset in how you approach stressful situations, and finally getting us to stop managing time and begin managing energy.

Predict the Future

Prognostication can be tricky. Even though we want to know what the future holds, most of us are afraid to commit to a path that will drive us toward success. Instead, we merely put some pieces in play and then see how this turns out. This is most evident by how people make committed New Year’s resolutions, only to see them disappear by mid-month.

Recently, I was talking with a friend about his son’s selection process for choosing a college. Making a sound college selection is an important factor in one’s success as an adult. My friend described to me how he and his son scanned campus websites, doing virtual and in-person tours, watched sporting events, talked with other students, checked in with his high school counselor, and spent time dreaming about how exciting his new life would be. My friend and his wife checked the tuition costs and available scholarships and talked to other parents about their experiences. In the end, his son based his decision mostly on a college that “seemed like the right place.”

Now I bet that this young man will do just fine at the university he selected and he will have a successful career and happy life. Yet, like so many decisions that we make, we often do not fully explore all the information that is available to us. Could he have spent a weekend or longer on campus? Should he have visited with some professors to find out about possible majors? Should anyone have told him the challenges that he can expect? Understanding the future means that you have as much information as you need to try to create the best outcomes.

Experts tell us that predicting the future is fraught with danger. Steve Ballmer, the former CEO of Microsoft, predicted in 2007 that “there is no chance that the iPhone will gain any significant market share.”xxxiv

Even people who broke other’s predictions didn’t believe in making their own. In 1974, Margaret Thatcher, who would become the first woman Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, posited, “It will be years—not in my time—before a woman will become prime minister.”xxxv

On December 31, 1999, while many of us were celebrating the turn of a new millennium, most tech workers were sitting in front of their computer screens waiting for the end of the world, as the Y2K event was supposed to stop all our computers and along with them power grids, stock markets, and even our clocks. Everyone was certain we would need a serious headache remedy cure for January 1, 2000, but the predicted disasters failed to materialize.

According to researcher Philip Tetlock in his book Expert Political Judgment, experts who try to predict the future fail or succeed based on two key approaches they may take in their prognostications. He calls these Hedgehogs and Foxes.xxxvi

Hedgehogs tend to rely on a single perspective to how they will make their call and are dogmatic about their expectations. Think about political pundits who have a certain agenda they want to promote and interpret everything through that agenda. They tend to be extreme in their predictions.xxxvii

Foxes, on the other hand, tend to be more agile in their predictions. They will draw on their life experiences to understand the world along with information from diverse sources. They tend to try out different actions and are willing to admit their mistakes, so they can learn from them. Consider a well-respected scientist who creates a hypothesis to test out a prediction and couches results as probabilities rather than statements of absolutes.

Furthermore, the truth is that we make predictions every single day, but we don’t always position them as such:

• Your partner asks you what is on your to-do list today and you think about what you expect that you will get done during your day.

• You prepare an agenda for your meeting with your boss to discuss your current work projects.

• You ask a colleague to go for lunch at a new restaurant because you heard their food is great and you hope that you will not be disappointed.

• Your mother calls you confirming that you’ll be coming over to her house this weekend for a family dinner.

Yet when I ask people to guess what their lives will be like outside of the parameters of this week or next, they are at a loss as to what things could be or might be. Taking a shot at where you might be in your career one to three years out seems almost undoable, as is how you think your company might grow over the next year. Yet taking a shot at where or how you want your life to be over the next short-time period can be a great way to avoid future shocks based on a lack of forward thinking. So let’s take a moment to have you make a call about your near future.

Given all you know about your current role and the current state of operations for your company, consider all the possibilities as you ponder the following questions:

• Where do you think you will be in your career in the next year?

• Where do you think you will be in three years?

• What do you think your company will be focused on in the next year and in the next three years?

• What will help you the most to achieve your goals and the goals of the organization who employs you?

We sometimes shy away from prognosticating because we see the risk involved in trying to predict what will happen, and most of us tend to be risk averse. We don’t want to make a decision that might be wrong, so we wind up making no decision. With no decision, we wind up creating more stress in our lives—due to the fact that by not taking charge of our future, we are giving up our sense of control. Knowing how things we do might turn out helps us moderate the potential of bad or wrong things happening. We are giving ourselves choices that allow us to take a deep breath and acknowledge that we actually have a role in our future. It’s not just fate that guides our life.

So what is the key to predictions? We believe it is all about creating choices. For most of us when we consider our options, we tend to look at one or two choices. I call it the “black or white model” of predicting. We tend to look at things in a binary way; it will be either this or that. In most cases, however, the world usually presents us with a color palette to choose from. I like to tell my coaching clients that if they look at the color choices on their computer, they will see that there are well over a million color choices to consider and although there are probably not a million choices we have for the decisions that we have to make, there certainly are more than two.

When it comes to small decisions, such as what you’ll enjoy for dinner, you’ll probably go with your experience. You love the restaurant’s salmon or its Sunday barbeque and you can smell those ribs on the grill. For bigger predictions, give yourself more choices. Take a look at the responses you wrote above and consider whether you went with your first gut responses to your future or your organization’s future or whether you considered a range of possibilities. You might have said you would be in the same position a year from now, but what if you opened yourself up to other possibilities? Maybe you’ll go back to school for a new degree, or you’ll ask for an assignment to a new department to get a feel for different kind of work. Expanding choices makes life more interesting and gives us a challenge that will help us grow.

Predicting the future is nothing more than putting yourself in the driver’s seat and deciding this is the route you’ll steer—how you want to live your life. By doing so, you’ll be identifying and getting ahead of any stress that is out there waiting for you.

Predictions start to build your stress hardiness, which is an important quality of building resilience. We like to emphasize hardiness during the preparatory phase of our resilience work, because the stronger an individual is as they prepare for stressful times, the better they will be able to handle stress when it comes their way. Although hardiness is often described as the ability to endure difficult times, we see hardiness as being the commitment an individual shows toward building up their strength and endurance in the face of anticipatory stressful conditions. We build hardiness in any number of ways that promote discipline and effort. By demonstrating patience in reading and researching all the available information on a topic to become a subject matter expert in your field, you gain not only knowledge but also confidence in your ability to discuss the topic. Encouraging your child to stick with a tough homework assignment to completion shows him or her that stick-to-it-iveness is a value worth possessing.

Get Gritty

The past few Boston Marathons may have been some of the most important in the race’s storied history given the tragedy of the 2013 terrorist event. “Boston Strong,” as it has become known, celebrated the fortitude and courage of that city by running the event without pause, setting an example of how Boston and our country would not be cowered by extremists. The city of Boston, birthplace of our nation, doesn’t cower very easily. The people of Boston showed their grit in 2013.

In 1967, the race experienced another kind of grittiness that also changed it forever.

Katherine Switzer was a young journalist student at Syracuse University. She loved to run and unofficially joined the men’s cross country-running team so that she could get miles in with other runners. During her training that took place during snowy New England days, she met a veteran runner of 15 Boston Marathons, Arnie Biggs, who regaled her with stories of the race. Soon, she caught the bug and knew she wanted to run the Marathon. There was just one problem, however: Women were not allowed to run the Boston Marathon.

Three weeks before the race in early April, she demonstrated to herself and Arnie that she could completed the race by running the full 26 miles in practice. She was physically ready to go but didn’t know what might confront her as the first woman to ever officially run the race.

She registered as K.V. Switzer and was joined by Arnie and her boyfriend, Tom Miller, who was a former All-American football player.

Conditions on race day were like many of her training days, snowy and cold. As the race started, many of her fellow racers welcomed her as the first woman to the Boston Marathon. Around mile four, a media truck caught up to her and started taking pictures. A few minutes later, however, the race coordinator, Jock Semple, jumped onto the racecourse and attempted to pull her down while screaming at her, “Get out of my race and give me those numbers.” He might have succeeded if Katherine’s boyfriend Tom hadn’t thrown a mean body block to get Jock off Katherine’s back!

She was shaken up and before she could collect herself, the media truck returned with reporters showering her with questions about “What is she trying to prove? When would you give up?” Additionally, another vehicle came along with Jock, who was now threatening her that she was in “big trouble.”

Katherine just put her head down and kept running her race. Although she had been drained of energy due in large part to these “extracurricular” activities, she turned to her coach and told him that now she had to finish just to show everyone that a woman could complete the race, even if she had to do so on her hands and knees.

As she approached the famous Heartbreak Hill, she found herself getting mad about how women were restricted from sports. Blisters started forming on her feet. She endured the pain telling herself that this race had become bigger than just a marathon run.

Four hours and 20 minutes after starting the race, Switzer finished and broke a barrier that went beyond running a race. As her father had told her a few weeks before the run, “Aw, hell, kid, you can do it. You’re tough, you’ve trained, you’ll do great.”

And she did.xxxviii

Psychologist Angela Duckworth has been studying grit for the past dozen years and has identified two major ways that grit is an important component of resilience.

First, grit is about how one deals with adversity and challenges and whether one persists in overcoming these difficulties. It is the classic idea of what we think about resilience that it is the ability to persist and bounce back from struggles. Many people face these situations in office settings every day.

Duckworth also identified another aspect of grit that has to do with having a focused long-held belief or passion. These may be represented by your natural strengths or interests that create an achievement orientation for you. With that kind of long-term belief in place for oneself, the opportunity for success and achievement has a greater chance for success. (This is also a common workplace phenomenon with top performers.)

Using these two broad measures of grit, she surveyed new students at West Point who were enrolled in a summer training program. This program which gave these new cadets a taste of what their academic experiences would be at the Academy, was designed to help weed out students who would not find the West Point experience to their liking.

Her concept of grit was a better determinant of which students would persist in the program than was the rigorous “Whole Candidate Score” that is used by the Army for admission.xxxix

Grit is important for us because it helps to build our fortitude and the stick-to-it-iveness that we need to succeed when things get tough. It is represented by a determination and commitment.

In a recent phone call, the head of an architectural firm specifically brought up the topic of grit, which he saw as a vitally important component of his firm’s culture. His organization’s cultural grit meant that they had to endure challenging times during their early growth period. It seemed like there were always difficulties in his business. Recently, he had to fire three people who were not good fits for his company, and the firm had lost several recent bids on projects that he thought they would win. Furthermore, he didn’t feel his team was working in as coordinated a manner as possible, which affected their productivity and, ultimately, their success.

When I asked how he was going to address this, his voice changed on the phone. It was almost I could see him sitting up in his chair. His response was clear. “Just like we always do when we’ve missed the mark on anything, we’ll pick ourselves up, refocus our efforts, and follow our plan. I’m not sure I know anything else to do.”

His words represent the key elements of grit. Anyone can develop and improve on the way build the storehouse of energy needed when adversity comes their way.

1. Embrace failure: We’ve been taught to fear and avoid failure. Failing is bad and you should work to never fail. This may sound like a great idea but it’s obviously very unreasonable and unrealistic. Failure is inevitable. Although it may be difficult to accept that it comes our way, changing our perception of how we deal with failure helps us see that it is not life- or world-changing and that, in fact, we get another opportunity tomorrow. Taking time to learn from that mistake is the key turnaround for growing from failures. Start small to understand and to embrace your failures. You’ll probably take your failure personally, but try looking at it objectively and consider that the failure was not all your fault.

2. Persistence: I like to say that getting my PhD is less a hallmark of intelligence and more about persistence. I have plenty of friends and colleagues who would agree with me regarding my intelligence. Persistence is about staying with a task that you believe is important. You already possess the persistence quality in activities that you enjoy. (“Eighty percent of success is showing up.”—Woody Allen.xl) For example, if you are a gear head and love working on cars, you have no problem spending your weekend at car shows and then playing around with your 1965 Chevy convertible. You’ll stay with that activity all day long.

Of course, being persistent with something we love is a bit different than persisting with something that is challenging or difficult for us, but once again reducing it to small parts can help us translate our skill with positive persistence. Time and focus are the keys to developing greater persistence, and you can experiment with those factors. One of my clients was working on a long and arduous technical manual for her company when she told me that she committed to working on it in 45-minute blocks of time that she built into her morning and afternoon work. It seemed that three-quarters of an hour was about all she could take, but it was enough to allow her to complete the task within the allocated time.

3. Focused passions: This is one of Angela Duckworth’s key definitions of grit.xli Having a long-held belief or value builds a path for your life that keeps a focus on importance. It may relate to family or your career. It could be as a result of a long-time drive that you possess or it could be tied to an event that occurred to you as an adult.

When Candy Lightner’s daughter was killed by a repeat drunk driver, she knew she had to do something more than just grieve her loss. She mobilized her energy and founded MADD, Mothers Against Drunk Drivers, with a mission to change the laws across the country so that drunk drivers could not kill other young people. Her campaign succeeded in not just changing the laws, but also changing our cultural thinking about drinking and driving. Hopefully, developing your passion will come through meaningful experiences and not tragedy.

4. Be open to shifting possibilities: As we’ve discussed, resilience to challenging events is more than a personal quality. It is also a cultural quality. When it comes to thinking outside the box, no culture may be better than the Dutch in terms of how they’ve dealt with flood management.

Almost all of Holland is within one yard above sea level, so for all its history it has dealt with flooding. We know about the Dutch systems of dikes and dams, that kept the water at bay for hundreds of years, but today their approach is different. It is not about keeping the water out but instead recognizing that they can’t stop the water and discovering ways to work with the water when it rises. Their current plan is to build wide trenches in several cities. They will use the dugout land to raise the level of surrounding areas to allow for new housing and offices. The trenched areas will become parks during periods of low water and rivers and lakes during periods of high water. Interestingly, many people in the local community were initially angered by this action. They believed Holland’s long-held theory that keeping water out was the best way to manage their flooding issues, but persistent discussion and communication paved the way for new ideas

Grit is an important quality in building strengths that we can rely on when times get tough. Our natural tendency is to want to confront the challenges we face immediately, but making sure we’ve built the behaviors to support the skill will improve our ability to succeed.

Creating Mindset

I am often asked, “What is the one thing that I can do to improve how I deal with stress?” Everyone wants to know what is the magic bullet that will help him or her gain some control over his or her stress levels.

If you only have time to do one thing, this section is for you. And that one thing would be how you think about the stress in your life.

How we think about the stress in our lives comprises our “mindset” about stress. “Mindset” is the collection of thoughts, ideas, and beliefs that directly impact the behaviors we manifest in dealing with stress. As we’ve noted, the stress management model has taught us that we should view ourselves as incapable of dealing effectively with our stress.

An amazing example of our negative mindset about stress is tied to a research project that tracked 30,000 Americans over an eight-year period. Abiola Keller and colleagues from the University of Wisconsin and the National Cancer Institute examined data from the National Health Interview Survey from 1998 and compared it to data from the National Death Index in 2006. Among the items that people were asked about were ones about perceived level of stress in life along with whether or not they viewed stress in general as harmful to their health. The researchers found an increased risk of premature death by 43% among those people who reported a high level of stress and thought that stress was a negative in their lives. The researchers recognized that although these statistics point to the power of negative thinking, they also acknowledged that having a more positive and resilient attitude toward stress could work to decrease its impact on our health.xlii

How we perceive and think about the stress in our life is what comprises our mindset about it. Most of us were taught (in our stress management classes) that the only reactions to stress are a “fight or flight” response in which we are only able to confront the stress or run from it. Although that is true from a purely physiological and body response perspective, the fact that we have a mind that is able to perceive and consider how we want to deal with stress, provides us with additional choices in how we see and experience our stress.

Perceptions represent a way that we often frame our own minds around stressful situations. If we see an upcoming stressful situation as a do-able challenge, then we can see ourselves as possessing the resources to adequately deal with that situation. If we view the same situation as something for which we do not have the requisite skills, then we see the stressor as a threat. Distinctions between how we approach these two mindsets are represented in Table 4.1.

However, sometimes our own perceptions of what is a challenge and what is a threat may be misperceived.

Case Study

In a recent consulting assignment, I was working with the senior vice president of operations and his direct report, the director of a specific division that was having operational difficulties. When I met with the division director, she shared her excitement about the project objectives that would help the operating team work together in a more coordinated fashion. The team had missed their production levels and there was a fair amount of infighting going on between work groups. She saw the project as vitally important and believed that her team would step up to the plate and do what they needed to do to improve the facility once the project objectives were embraced.

The team member who was overseeing the facility had a totally different view of the project. He perceived it as dangerous, in that it forced people to work as a team when they didn’t have the skills or interest in working together and that, in turn, would only yield an angry workforce. And an angry workforce would make more production errors. He didn’t want to move ahead on the project, thinking it was better to do nothing than risk creating more divisiveness.

Was this project a challenge for the operating team? Or a threat?

Many of us fall victim to experiencing a negative perspective on a regular basis. The negativity bias, which has its origins as a protective biological factor going back to our early ancestors (“I better watch my back while I’m out hunting for food to make sure that the saber tooth tiger is not hunting me”), continues to influence our thinking. Simply put, when we think the worst will happen rather than the best, we are falling prey to the negativity bias. Consider how you respond to either a negative or a positive situation in your life. When the negative situation happens, you may say, “I expected that to happen,” or, “These kinds of crummy things always affect me.” When a positive happens, you may think, “Boy, am I lucky. These kinds of things never happen for me.” We tend to expect negatives and discount positives.

In situations where we manifest the negativity bias, we see the world or situations as more threatening and dangerous, rather than seeing challenges that can be interesting and perhaps even exciting.

What if we turn the table on the negativity bias and actively create a perception that stress is not bad, but instead is something good. The idea that stress is good for us derives from the notion that by challenging ourselves we create opportunities for growth and success.

Recently a young client of mine received word that she was being promoted to her boss’s position as he went off to a new job himself. After I sent her a congratulatory e-mail, she sent me back the following response, “Thanks! To be honest I am still quite shocked, nervous, and overwhelmed but up for the challenge.”

Creating a positive stress mindset takes some time and an openness to see the world a bit differently. Researcher and professor Carol Dweck at Stanford University has identified that each of us approach learning in one of two ways. People with a fixed mindset tend to see their world as static and don’t believe that change happens very easily. Fixed mind-setters believe that their world is carved in stone, that they have to make the best of what they have, and that there is little opportunity for growth. People with a growth mindset see the world in a different way. They believe that their inherent talents are meant to be stepping stones that will help them achieve and grow more. They are learners and are constantly striving to improve on their capabilities and performance.xliii

If you have a growth mindset and want to begin to see how you can approach your stress differently, creating an affirming mindset will help you set the stage for decreased stress and more resilience. There are any numbers of strategies you can use to change how you perceive the stress in your life. Additionally, you can build this capacity on the front end during the preparation phase of the Resilience Continuum, so that you get a jump on any predictable or even unpredicted challenges. Some of the strategies you can try:

1. Change your self-talk: When something good happens, don’t tell yourself you are lucky; tell yourself you are good. When something bad happens, don’t make full attribution to your effort; spread the responsibility around.

2. Don’t merely focus on failed efforts, but move to the next outcome that you want. Dweck found that students with fixed mindsets wanted to know how they did on school tests, whereas students with growth mindsets asked what they could do to improve.xliv Careful analysis means that you consider what you did poorly, what you did well, and exactly how you will do things differently in the future.

3. Experience something new. This may be travel or volunteer work or even reading a non-fiction book if you’ve always been a fiction reader. Doing something new helps create new neural pathways and teaches you something you did not know before. It’s highly possible that the new learning opens up a new perspective for you.

4. Stop telling yourself that stress is bad. This is a big one for us. We see people walking around their office every day complaining about the stress level in their job. “It’s so stressful here,” has become a meme in many workplaces. As we saw in the research study cited above, believing that stress is a negative contributes to increased mortality. We wouldn’t be surprised if it also contributes to hating our work. Instead, if you are having a really tough day, try telling yourself, “Today is a challenging day, but I am doing okay.”

5. Take on a challenging assignment at work. Many people are content to just do their job every day and some of them do that for 25, 30, or even 40 years. Imagine how much they are missing from not pushing their own learning to see what they can achieve. It may seem scary to ask to do more work, but most probably you’ll do very well, develop a new skill set, or even become a thought leader in your organization, and you will be pleasantly surprised by your new-found success. Remember, some things can’t be taught, they can only be learned.

Events, even stressful events are neutral by nature. They just occur. How we perceive, judge, and experience them is what creates the stress in our bodies. How you approach stressful situations in your mind (your mindset) may be the closest to a magic bullet for addressing stress successfully. A positive stress mindset builds fortitude or hardiness in the face of challenges. And this mindset we want to build begins by being open to the idea that stress is not the enemy but is really your friend. Embracing it rather than fighting it will create a great deal more ease and resilience in your life.

Your Most Precious Resource

There are only 24 hours, 1,440 minutes, or 86,400 seconds in a day. That is it. When that second hand ticks to the next second, that prior second is lost. There is no more and no less. We can’t increase that time and although we think we manage time, we don’t do any better at that than we do with stress. It’s another one of those imperatives.

The truth is that time manages us better than we think we manage it. Our effort to address time is determined by how we spend it on our different activities. Those activities that we spend more time on are our de facto priorities. Those we spend less time on become our less important priorities. Say, for example, that you are planning to go to the gym to work out, but instead you get enthralled with your friend’s vacation pictures on Facebook. You wind up Facebooking instead of working out, which is fine. Oftentimes, folks will get upset and stressed out later about the choice they made. I would encourage a more accepting and forgiving approach to time. No need to feel bad. At that moment, being on Facebook was more important to you than exercising.

Time is really about priorities. We do have time, 24 hours daily, and time to decide how to apply it. “I don’t have time for my daughter’s soccer match” means you’ve decided not to go (perhaps with good reason, perhaps not), but that excuse is faulty because you have the time, you’ve just decided that it is not the priority for you that day.

Most of us spend as much time trying to manage time as we do actually spending time doing things. We make lists, we revise our Outlook calendar, we write notes to ourselves, make meeting requests, fill in our manual date book. If you are like me, I’ll even tell Siri to make an appointment for later in the day to remind me to make an appointment with someone! Our effort to manage time is probably doomed to fail due to the limited and finite nature of this commodity and the vast number of distractions that exist in our lives.

We may want to ditch time and instead focus on something we can control such as our own personal energy.

Energy is the ability to get work done. Energy exists in different forms. One type of energy happens when your work is going well and you are feeling positive about your projects. You feel pumped, excited, and strong. Your smile and “can do” encourages everyone around you. You are an energy creator. Alternatively, there may be somebody at your workplace who is an energy drainer. Perhaps he or she is the person who is always complaining and whining and not getting things done. They suck the energy right out of the room and after spending time with them you may feel like you need a nap.

Energy management is particularly important during this preparation phase of the Resilience Continuum, because there are several ways you can approach it. One approach relates to the amount of energy available to spend during the day. Energy management, in this instance, has to do with the amount and quality of rest you’ve had, how you build endurance, and how effective your energy management strategies are during the day.

A second approach is about how you create or build your energy storehouse or robustness. This has more to do with how you approach your own health and wellness. Exercise is a good example. Some people who exercise at the end of the day may say that their exercise routine helps to work off their stress, whereas the people who exercise in the morning often say that their exercise gives them strength for the day. Nutrition is another example. Eat a heavy starch-filled lunch and you’ll be struggling to keep your eyes open until your system works that off. Eat a protein-rich lunch and you’ll probably be more focused on your afternoon tasks. Recognizing how your body works and making the choices that fit you means that you can endure more challenges and difficulties and have the storehouse of liveliness to get through your more difficult stressors.

We have within our daily capacity only so much energy that we can expend. You wake up in the morning and may feel rested. By the end of the day, you are fatigued. What happens during the day is the difference between that energy potential in the morning and the energy exhaustion at the end of the night. Restoring our energy relates to the quality of our sleep and understanding your personal sleep requirements (not what they say on Yahoo news) is your key to rebuilding your energy storehouse overnight.

Even if you’ve had a bad night’s sleep, it is possible to create restorative energy during the day. Remember when you were a kindergartner and you were able to put your head on your desk and rest. Not such a bad idea. Recovering energy during the day is a doable task. My wife, Sheila, takes Zumba classes and tells me that after moving non-stop for 60 minutes, she feels more energized than she did before her class. She likes to say, “Dancing doesn’t take energy; it makes energy.”

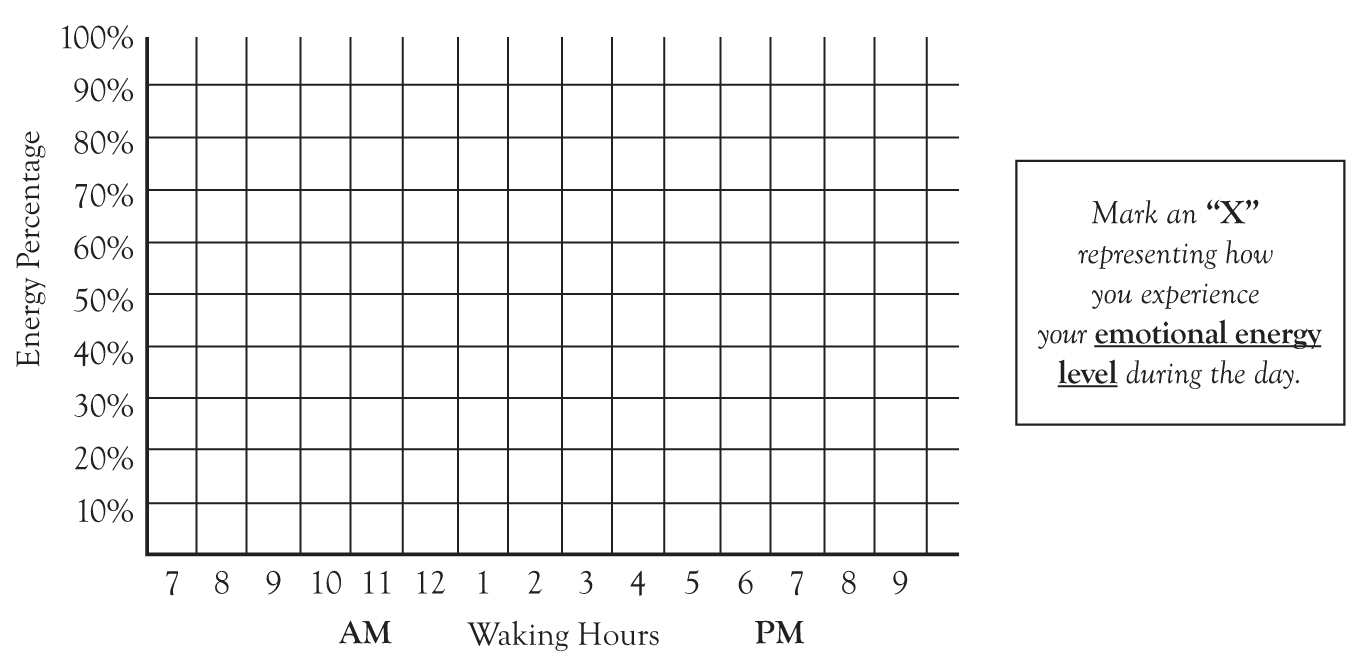

Let’s examine some factors around personal energy. First of all, everybody’s energy timing is different. In my house, I am an early riser usually getting up around 5 a.m. I take an early morning walk and am ready to start my day writing or preparing for clients by 7 a.m. As the day progresses, my energy begins to dwindle and by the evening, I’m pretty pooped. My wife, on the other hand, is a slow starter in the morning but gets focused as the day goes on. She is likely to stay up writing a blog post or article long after I’ve gone to bed at 9:30 or 10 p.m. Energy levels are different for each individual. We can use an energy tracker to monitor how energy ebbs and flows during the day (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 Energy Level Tracker: Physical Energy

Figure 4.2 Energy Level Tracker: Mental Energy

Figure 4.3 Energy Level Tracker: Emotional Energy

To use this tracker, merely record your perception of how much available energy you have each hour of the day. Most people will use the tracker to record their physical energy levels, but you can also use this to track your mental or emotional level. You will want to record five days of data, including a weekend day, so that you can get a good read on how your energy levels run during the week.

The second element or key idea about personal energy is that all hours are not created equal. Building on idea one, you may know that you are a more creative thinker in the morning and that by mid-afternoon you’re better off completing expense reports rather than drafting an operational plan, since your creative juices are shot. On the other hand, it may be better for you right after lunch to do something that involves filling out mundane paperwork, because you have to try to work off that after-lunch lethargy. Better to do that than to schedule a meeting with your boss where you may find yourself drifting off to nap. Paying attention to how your energy shifts during the day is really important, and this is one of the ideas that is missed by many time management people. For them, all hours are created equal, but for personal energy people, all hours are created differently.

When do you do your best work? What kind of work are you doing during that part of the day?

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

When do you do your worst work? What kind of work should you be doing during this time of the day?

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

The third key idea in energy management I alluded to a little bit earlier when I talked about my wife’s Zumba class. You can create more energy by doing things that you find fun and enjoyable, including in the workplace. Now, we are not going to have the time during the day to do everything that we find enjoyable and fun, but we want to make sure that we build in things during our day that are rewarding to us. That will give you more energy.

I worked with a senior leader who found his energy levels draining during his meeting days, as if someone had pulled the plug on his own energy storehouse. He recognized that there were two things that were missing from his workday.

First was time for quiet reflection, when he could have built in structured minutes to think about the big picture and to give his mind a break from the daily routine of problem solving and issues management. The second was time to meet and talk with his line staff to see what he could learn from them. He took a deliberate approach of asking his staff, “What are you working on that is exciting to you? What are you working on that is frustrating to you?”

As we worked out a plan, he decided to put these two practices on his calendar several times a week. He told his assistant that these were sacred times that he did not want to be disturbed. Today, he reports that when he is able to hold that time in place, he feels enlivened and more productive. Plus, it helps his team to see that he is committed to being with them.

According to William Anthony, a researcher at Boston University, napping has a powerful effect on physical and mental restoration, with gains being made even with a 15-minute power nap. His survey research indicated that over 70 percent of those surveyed reported that they’ve napped on the job. Companies such as British Airways and Union Pacific Railway encourage their pilots and conductors to take 30-minute naps with proper safety procedures in place. Of course, if your workplace does not support this kind of action, you can at least know that you can always go to the “rest room” for a little quiet time.

The fifth and final key to personal energy management is about using our personal energy dashboard. Our car’s console has a fuel and temperature gauge, speedometer, and odometer that keep us informed about our car’s performance. Today’s advanced vehicles use state-of-the-art computer sensors to manage the car’s temperature, alert us to when we are getting too close to another car when parking, and are even able to prepare our car to slow down in traffic due to radar housed in the front grill. What if we can begin to apply technology for preparing and tracking our stress levels, so that we are able to better understand how our body is preparing and reacting to a particular stress, providing us with an opportunity to be mindful about how we choose to respond? Energy trackers, like the Apple Watch and Fitbit, are leading the way in helping us gain insight into our own energy management.

Digression: Be aware that the job requirements for energy should at least roughly match your personal “battery.” If you put a small battery into a huge energy role, such as a nurse, for example, you will see errors of commission in terms of doctors’ orders and administering drugs.

If you put a strong battery in a low-energy job, such as a TSA screener, you will see errors of omission as boredom and tedium dull one’s senses.

We really don’t want exceptionally low-key nurses, nor people on the TSA monitors at airports who have high energy and are bored looking at all those bags all day long.

Our personal energy is our most valuable commodity. Some people think that time is the most precious factor in our lives, but it is actually energy, because we can control our energy while we can’t control time. How we use our energy determines our success, our victories, and perhaps even our happiness.