Overcoming Your Negativity Bias: Creating Your Future and Not Accepting Your Lot

We are biologically programmed to think negatively. And it is a good thing. Managing potential dangers is a far more important survival strategy than being a Pollyanna and hoping that everything will somehow just work out.

Research on risk and reward tells us that the pain of loss (financial, for example) inflicts much more pain than the amount of pleasure we feel from the successes in our lives, so it makes sense that we protect ourselves against danger and loss. That is important to remember as we build our resilience and recognize that thinking negatively is not a sign of weakness but is instead an indication that we are making ourselves sure we are safe.

What if, however, we were able to rewire our brain, so that the preponderance of negative thinking doesn’t take such a prominent role in our day-to-day activities? We’ll examine ways that can change our brain thinking, so that we build hardiness against negativity and create new ways to create the future we want.

The Seduction of Negative Thinking

Let’s establish that “it’s good to think bad.”

It can be a dangerous world out there. Maslow’s foundation in his famous hierarchy is for survivallv (Figure 7.1). Every college freshman encounters this (or at least they once did when there were liberal arts curricula):

Figure 7.1 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

If we’re threatened at the physiological level, we’re encountering “bad stuff” around us.

The correct degree of vigilance is important for our protection. Whether it was walking on the Serengeti during primitive times, when predators were common and protection crude, or driving defensively on today’s interstate highways, we need to be aware of potential danger, not solely the danger we see. By “correct degree,” I mean stopping short of the paranoid. The screeners at the security points in airports today are relieved frequently, because you cannot remain at a high degree of vigilance in otherwise boring and mundane jobs (staring at monitors or, for that matter, staffing ICBM silos).

Nonetheless, there is a value in negative thinking, and we should escape from the rubrics of “stop being so negative” when, in fact, it is only prudent to do so. For example, if you overpromise something to a customer, you’re sunk. Even if you deliver well, it’s not going to be enough.

“This will be the most successful promotion of all time.”

“We’re going to break sales records.”

“This will be the party to end all parties.”

No matter how good, it’s not what was promised.

But when you under-promise and over-deliver, you’ve changed the mindset. To do this, you need to be able to think of “worst case.” What happens if I promise the moon but only deliver Chicago? There is wisdom in creating dynamics where you try to ensure success but also protect yourself from venturing into unavoidable failure.

Marshall McLuhan: “The price of eternal vigilance is indifference.”

In some companies—and in some relationships—no matter how successful you are, you just can’t “win enough.”

Great year, Trudy, but of course not quite as good as you did last year.

The most important lesson is that while some negative thinking is inescapable and probably quite prudent, we can become victims of the sirens’ song of negativity and adopt it as a lifestyle and business strategy. And that’s what we are warning you to stay away from, loud and clear.

We tend to give more credibility to negative ideas than to positive ones. Research has shown that our brains react more powerfully to negative possibilities (fear about survival) than positive possibilities (hope in some potential). The more immediate gratification tends to be protection, not innovation, certainty and not risk.

A research study by Tiffany Ito and her colleagues at Ohio State University showed that students, when shown positive images (e.g., a Ferrari or tempting food) or negative images (e.g., a dead cat or a lost cause) produced different brain activity responses. Neutral pictures, such as a hair dryer or fire hydrant, produced disinterested responses. She discovered that the negative response generated a greater surge in electrical activity than positive or neutral images. She concluded that our emotions are most influenced by negative events and that biologically we are still programmed to focus more on the negative.lvi

More obvious examples of this can be seen in the media daily. The approaches used in local news programming, for example, are highly negative: threats, floods, accidents, disasters, and disappointments. The “good news” is usually a human interest story about a lost cat reunited with its owners—after some harrowing experience. Listen to the sound bites and read the headlines. You’ll never hear “Record number of new jobs created!” but rather “Experts fear record number of new jobs hiding a basic structural flaw in our economy.”

Politicians are consistently negative. They all decry the negative ad and mudslinging, but then engage in it with gusto. They are advised daily that negative images arouse more emotion and cause more action than positive ones. They would rather talk about a rumored homophobic statement uttered by the opposition 25 years ago, than talk about their plans to reduce spending and balance the budget in the next four years.

We see rather tasteless comparisons of brand advertising versus “Brand X” and we hear almost hourly of the next food scare: red meat, sugar, salt, gluten, fat, and diet soda. The Internet makes negative rumors far worse and adds to the unscientific noise. If you don’t believe that, consider the children dying from measles in the 21st century because their parents are afraid vaccinations will hurt them.

We have to migrate from a default to negative thinking to a natural embrace of positive thinking. We are beyond the survival stage. The Serengeti is no longer a danger, and we are rational enough to know that we should be careful driving, walking down unfamiliar streets, or eating yellow snow.

The Universal Need for Positivity

At the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, a young Tanzanian athlete named John Stephen Akhwari ran the marathon and finished last. Yet his story perhaps as much as any other runner at that event won the admiration of the world.

Unaccustomed to running at 7,300 feet, Mr. Akhwari suffered leg cramps early in the race but continued to run. At one point, he collided with another runner, fell, badly injured his knee, and dislocated his shoulder, but he continued to run.

The other runners, all world-class athletes, finished the race within the expected range of 2.5 hours, but Akhwari, wounded and in pain, entered the Olympic Stadium a full hour after the second to the last competitor crossed the finish line. Almost all the spectators had left as the award ceremony was over, but soon a vehicle with flashing lights entered the arena to announce that another runner was coming to finish. The few thousand attendees cheered the Tanzanian as he hobbled around the track and crossed the finish line.

In his post-race interview, the media asked why did he even bother to finish the race since he had no chance of winning. Mr. Akhwari was incredulous that such a question was asked and his response shows the capacity of individuals to overcome the negativity bias that pervades our culture and biology. “My country did not send me 5,000 miles to start the race. My country sent me 5,000 miles to finish the race.”lvii

We have all had experiences that have shown us that we just have to stop being so negative. I tell people all the time that our dogs don’t stop at an accidentally open gate and do a needs analysis, or a risk/reward ratio, or assess the upside/downside. They race through an open gate as any self-respecting dog does, consequences to be considered later—usually much later.

Another rainy day on our vacation. (Yes, but we’ve had four good days out of six so far.) We seem to default to bemoaning our fate rather than putting things in perspective.

The importance of positive thinking (and it’s natural companion, positive self-talk) can be seen, empirically, on a daily basis. When we talk about our gratitude, appreciation, hopes, aspirations, prayers, and even wishful thinking, we are guided by the positive. Like our runner above, people don’t enter a race or competition merely to finish, they enter to do the very best they can. A “personal best” is often more rewarding than a champion’s expected win. I’ve never heard cheers at a sports event that sounded like this:

“Just try to finish!”

“Go for the bronze!”

“Just don’t embarrass yourself!”

This is even truer in business. You don’t want to come close to a sale, you want to make the sale. There are no bonuses for “almost” or for merely persevering. (This is why the “rewards for self-esteem” for merely showing up in grade school events are actually so damaging. They don’t replicate reality at all and give a false sense of achievement, which will eventually erode self-esteem.) At work, we hope for the best and plan for the worst, and create sometimes elaborate scenarios for both. But we don’t sit back and feel that we’re doing fine by our mere presence.

Resilient thinking requires that we focus on how to recover from negative, tragic, and traumatic events. Resilience places us back on a positive path after the brief detour of setback.

The following is an excerpt from Alan’s soon to be released book, Million Dollar Maverick:

I’ve found that most people don’t trust their own judgment, so they tend to trust other people’s judgment, which may be entirely wrong for them (or lousy, period). Or they use trial and error, an extremely expensive and risky means to make decisions about their lives.lviii

On the left of Figure 7.2 are what we consider the keys to building trust in your own judgment:

Figure 7.2 Trusting Your Judgment

1. Recognition of success. Know what constitutes success for you. Hint: It should never be perfection, but “merely” the attainment of important goals.

2. Positive self-talk. You should start and end the day with the positives in your life, what you intend to accomplish, and what you have accomplished.

3. Healthy feedback intolerance. You can’t listen to people whom you haven’t asked, because unsolicited feedback is almost always for the sender’s benefit. This conflicts with the “humility school” people who tell you all feedback is good feedback. It isn’t. Listen only to those you trust and you ask.

4. Appropriate avatars. Whom do you admire? What traits are important? Everyone talks about Steve Jobs’s wonderful stewardship at Apple, but he was an impossible boss, husband, and father.

5. Dynamically growing skillsets. Confidence in judgment is buoyed by rising competence in diverse areas.

6. Social cue adeptness. You should be able to recognize when to speak and when to listen, which requests are appropriate and inappropriate, when to offer help, and when to mind your own business.

7. Judgment. As Jefferson observed, “In matters of taste, swim with the tide; in matters of principle, stand like a rock.”lix

Your judgment will then lead to better decisions and behavior to achieve your defined future (success), and also serve as a contingent reserve when you experience a setback and need the resilience to bounce back and not be defeated.

I call the seven traits “hyper-traits,” and the trust in your own judgment your personal gyroscope, which keeps you on balance, upright, and headed in the right direction.

Think about the most successful—and respected and sought after—people in your business or office. They are universally positive. They provide a ray of light, not a dark dead end. They are people who others want to follow, not avoid. They seem to do more than simply make lemonade when given a lemon, they instead create a lemonade industry.

The cycle is inviolable. Positive people create energy, which others thrive on, which gives them still greater energy because of the highly charged people they’ve attracted. They are the ones normally chosen to lead, to advise, and to coach.

I tell consultants whom I coach all the time: Enthusiasm in contagious. If you’re enthusiastic—positive—your prospects will be, too. When you’ve met a succession of apathetic customers, the odds are it’s not them, it’s you. We all give off “vibes,” the positive and negative vibes are among the strongest and easiest to detect.

Rewiring our Brains for the Upside

Our brains seem to have an “all or nothing” default. Try this experiment:

Start reading an article at your desk and also turn on some music that you’ve not heard before. Can you read and comprehend the material while listening to the music, especially lyrics? Test your comprehension by writing a summary of the reading and of the music. I’m betting you can’t do it. The vaunted “multitasking” doesn’t always serve as our brain’s favorite operating system.

What we consider to be multitasking, in fact, is more accurately “serial-tasking.” Our brain moves back and forth, to and fro, between activities but we don’t concurrently focus on activities. (Another example: Have two people speak on each side of you in different conversations, and try to respond to both. This actually happens in many social situations and a lot of bars!)

We really don’t focus on two or more activities at the same time, at least not terribly effectively or successfully. We often talk on the phone while trying to pay bills, but the payment or conversation will suffer. This is also why people texting stop dead on the sidewalk, stalling people behind them: They can’t text and walk successfully simultaneously! (And this is why texting and driving is so terribly dangerous. Studies have shown that even hands-free phones are dangerous, because people engaged in conversations lose focus on their driving—it’s not their hands that are the issue, but their brains.)

Dr. Michael Weisand at the Wright State Research Institute calls the “winner take all” attitude that of the primary brain focus.lx For example, if you are perusing a menu at your favor restaurant, and the options include herb-crusted lamb loin, soft-shell crab tempura, sautéed golden rainbow trout, heart of rib eye filet, and cauliflower steak with Indian curry, your mind begins to swirl with the choices. But once you choose, all other options drop off a cliff of contemplation, and you’re salivating only for that “winner.”

And your mind proceeds to its next task, perhaps the best wine to go with the meal.

Case Study

Union General George McClellan, a renowned martinet, was sometimes found dictating four letters concurrently to four different secretaries when visitors arrived. A subordinate found out later that all four had to be redictated, separately, after the visitors had left.

Most of us deal with stress through negativity bias, as explained previously, so that “winner takes all” is a negative priority when it comes to our perceived stress reduction. We say things such as, “I can’t handle stress,” or “I’m overwhelmed.” We stop thinking about how to overcome—positive interventions—and surrender instead to the notion that we can’t overcome the overwhelm. The negative “takes all.”

Negative thinking also narrows our thinking. We focus on survival, Maslow’s lowest level of need, and limit out choices because we seek only safety and relatively small goals. This can result in unhealthy choices for us: poor diet, easily angered, excessive risk taking. The latter is often manifested by risky driving, excessive gambling, and addictions. We are redirecting self-anger to try to preserve our identity while venting. Our own negative thinking, surrender, and anger limit our thinking about how to positively respond to problems.

This is why overcoming negativity bias is so important and such a personal pursuit. Think of the different responses you see every day to relatively minor incidents:

• A driver cuts you off.

Forget about it.

OR

Road rage.

• Someone hits their elbow on a drawer.

Laugh and rub it.

OR

Curse loudly and scream at whomever opened the drawer.

• The stock market goes down 200 points.

Be happy that you’re in it for the long term.

OR

Manically call broker and demand changes in portfolio.

• Your computer freezes.

Call for help and move to lap top or other work.

OR

Scream at repair people that you want special priority response.

• You’re placed on hold by airline.

Check your e-mail while you wait.

OR

See the and call back repeatedly trying to get someone.

As you can see, these aren’t so far-fetched! When you include more major issues, such as a car breakdown on the highway, a warning from the IRS, or a relative taken to the hospital, the response has far more dramatic implications. So the focus we use needs to be positive: What are my options? How can I improve this? What resources are available? This is far better than the negative: Why is God against me? Who invented this crap? Why is my tax money being wasted?

I’m suggesting that positive thinking, in light of the “all or nothing” mentality, requires focus on one task at a time. We have been lulled into thinking that concomitant tasks can be accomplished at once because they seem related. But what the computer seems to do concurrently (which is actually just ferociously fast serial processing) has subverted our thinking about what we are capable of doing well.

We don’t order the trout and filet together and eat a bit of both, because they don’t complement each other and choosing a wine would be very difficult. We can’t expect to write a report and talk on the phone simultaneously and expect both the call and report to be done well let alone listen to music, deal with our small child, pet the dog, figure out how to get the squirrels off the bird feeder outside the window, and worry about the overdrawn amounts in the checkbook!

Yet, that is not only what we tend to do, but we actually have convinced ourselves that we’re good at it. We are not. We’re terrible at it. And we endanger our decisions at best, and our lives at worst, when we allow that fiction to influence our choices of behavior.

Airline pilots have landed at the wrong airports, have feathered the wrong engine (the cause of a huge Asian air crash not long ago), and used the wrong radio beacon (resulting in a horrible crash in South America). One cockpit recording of a commercial airline crash in California, caused by hitting a smaller plane, revealed the two pilots, plus a supervisory pilot in the jump seat, were all talking about the company retirement plan changes when the accident occurred. Everyone on board was killed.

I’m not talking about exhaustion (the problem with many long-haul truck drivers) or impairment (drunk driving). I’m talking about a deliberate but often unconscious bias toward doing many things at once with potentially disastrous consequences. We can see this in major corporate decisions, such as acquisitions and divestitures, and in major personal decisions, such as selection of a college or job changes.

We need a positive approach, a rewiring of our brain, guided by a focus on the immediate or priority task at hand. You can’t call the computer repair people to fix your brain.

Being Positive Is Not Enough

We need more than mere “happy thoughts.” The old “positive mental attitude” of Napoleon Hill and W. Clement Stone are pretty much artifacts of a simplistic age. (Stone made a Fortune worth about $450 million being brilliant in the insurance business. He developed a positive mental attitude because he had $450 million, not the other way around. His etiology was mixed up. When Alan told him this, as president of one of his companies, he was promptly fired. His attitude wasn’t too good that day!)

Disney has advocated “wishing upon a star.” We’re told not to be dreamers. Yet we also hear from highly successful entrepreneurs that they’ve always had a dream. Being a dreamer who dreams of winning the lottery or a job promotion will not, as Captain Picard used to order, “Make it so.”

So what is the proper amount of dreaming, aspiring, and visualizing?

Gabrielle Oettingen, an NYU psychology professor, has researched the impact of positive thinking and dreaming in term of the aspirations one believes are important. In her book, Rethinking Positive Thinking, she concludes that merely thinking good thoughts is not enough to get people motivated sufficiently to act on their dreams, and it may, in fact, be an impediment.lxi

She had two student groups engage in an exercise where one group was told to fantasize that the following week would be fantastic for them—great parties, good grades, good health, and so on. The other group was told to simply record their fantasies for the next week, whether they were positive or negative.

Those who fantasized a great week accomplished less, in review of the week’s actual activities, than did the other group with more neutral thoughts. Oettingen believes that positive fantasies may create a kind of complacency that “just wishing will make it so.” What is actually needed to be able to take positive thoughts and act on them successfully.

Hence, when people with positive thoughts were able to identify obstacles in the way of achieving their goals they had a far better chance of acting on their dreams and achieving them. They had to act on the impediments, once identified, and could not be complacent with the mere wish.

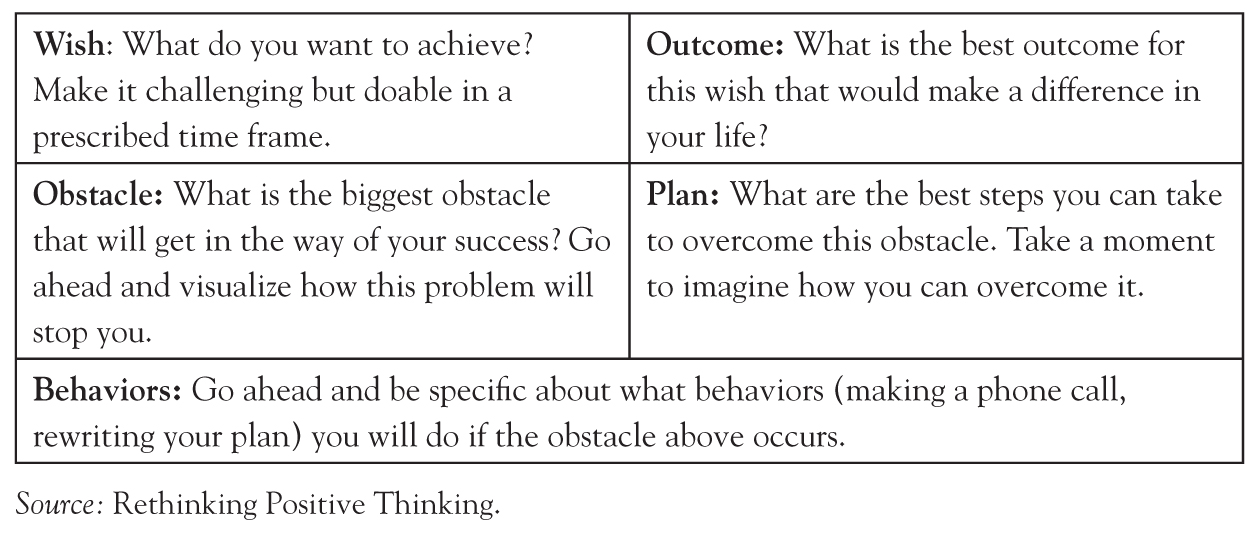

Her process is known as WOOP:

Wish. First define your goal, anything from weight loss to landing a new sale.

Outcome. Imagine what the best possible outcome for you is, such as excitement, pleasure, money, recognition, and so forth.

Obstacles. After the dream and outcome, identify the roadblocks to success. What can keep this from happening.

Plan. Now that you know the roadblocks, plan to prevent them from occurring or mitigating their impact if they occur.lxii

We’d add a fifth factor to the model to say what are the specific behaviors that you can take to put your plan into action.

Try WOOP for yourself. The intent is to help change your thinking patterns in a variety of settings, personal and professional. Try this in a quiet place, and give yourself 15 minutes, letting your fantasies focus on what you truly would like to accomplish:

Table 7.1

There are two ways to change your life. You can change the way you think and when you do that, you will change your behavior. Or you can change your behavior, and with new successes, you will change your thinking. Gabrielle Oettingen’s WOOP process helps us do both. By realistically dreaming about our aspirations and targeting specific behaviors to overcome what has kept us from success, we can begin to make those positive dreams a genuine reality.

Finding Your Superpowers

Each of us has uniqueness not shared with others. Call this your “superpowers.” Fortunately, no phone booth is necessary for a change of clothing, a la Superman, since phone booths have disappeared, but your superpowers have not.

One of the primary reasons that we don’t feel good about ourselves, suffer from low self-worth, and lose resilience is that we often wind up doing things we're simply not good at doing. We take on a job, launch a career, engage in a hobby—because someone ordered us to, or suggested it, or because we feel normative pressure. We have to overcome our basic lack of affinity for the endeavor, which is draining and, sometimes, impossible.

The natural antidote is to focus on things we do well, professionally and personally. Just because some parents created a wonderful company doesn’t mean the children should be expected to run it. Just because your mother is a dentist doesn’t mean you need to be. Most people look absolutely idiotic with their baseball cap on backward, especially when they then shield their eyes from the sun with their hand. But normative pressure forces us into dumb situations if we yield to it. (Think of how those tattoos on Millennials will look in 20 years when they’re striving for senior leadership positions or when what was a butterfly has morphed with sagging skin into Godzilla.)

Superpowers are often called merely “strengths.” There is a plethora of books on finding your strengths, measuring them, and assessing them, but often the books assume you're damaged if your “findings” aren’t consistent with certain strengths. They deny your uniqueness and try to drive you back into the herd. They don’t advocate your superpowers, they advocate their superpowers.

One of my coaching clients, a CFO of a publicly traded company, was a smart fellow whose greatest superpower was that he was a very thoughtful and strategic thinker who could successfully analyze most situations. His greatest weakness was how he dealt with people. He would lose patience with people and get easily aggravated if they did not understand the subject matter he was discussing, which was often about financial matters where they were not nearly as skilled in understanding as he. This caused him and his colleagues a great deal of stress.

In order to help him build his resilience to these kinds of situations, we decided that we would use his superpower of being able to analyze a situation before he approached it to determine exactly how he would deal with the “human side” of the equation. Given these understandings, he could then make some choices around the behaviors he wanted to show to others, such as being a better listener, educating them about the subject matter, or even deciding to delegate the task of a particular meeting to his controller who was better with people than he was.

Using his superpower of “being a great analyzer,” this CFO was soon seen by his colleagues as much more supportive and understanding, not as not someone who just created more stress for himself and others.

One of the greatest issues with superpowers is that people won’t admit they have them! Too many of us deny that we’re really superb at some things, and tend to think that “humility” is some kind of key to the entrance to heaven. (In 30 years of consulting, Alan has never heard a buyer proclaim, “Get me a humble consultant!”) I don’t want a humble heart surgeon, I want one who believes he walks on water. I don’t want a humble athlete with the ball at the key point at the end of the game, I want someone who calls for the ball or wants to be at bat because he or she thinks that’s the team’s best hope.

Do you “call for the ball”? Your negativity bias may be giving you the message to not go for it just in case you fail. That fear is what often prevents us from admitting to and owning our superpowers.

Here’s a simple exercise to focus on superpowers and overcome humility, called “Frame It/Name It/Claim It/Aim It.” It’s important for better understanding our greatness.

Frame It. What is the context with which you want to use your superpowers. We’ll assume it is for good and beyond that is it to achieve some new skill at work or to

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

Name it. What words or phrases describe some of the things you do well? Consider terms such as intuitive, analytical, empathic, action-oriented, and so forth. What have others told you that you do well?

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

Claim it. Pick one of the superpowers above and provide specific examples of situations where you have employed them effectively. This will help with your recognition in your accomplishments. This is usually the most challenging part of this exercise since most of us are afraid to acknowledge our successes.

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

Aim it. In what ways can you begin using the superpowers for similar accomplishments tomorrow? Consider how you can help others with some challenge or overcome stressors you are dealing with.

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

Your superpowers are untapped resources for building resilience. Avoiding the negative and focusing on the positive will build your strengths and drive you right through adversity.