Lean, Six Sigma, and Lean Six Sigma

Voya, a financial services firm, pulled off an IPO in May 2013, raising $1.27 billion. This was actually a spin-off from its corporate parent, ING (the largest bank in the Netherlands). The main reason for the transaction was to help pay down the obligations from the bailout that had resulted from the financial crisis in 2009.

But with the deal, the management of Voya saw this as an opportunity to transform the organization, such as by reimagining the culture and streamlining the operations.

Note that Voya was a hodgepodge of different companies because of a long history of acquisitions. This meant that there were a variety of cultures within the organization. This made it tough to carry out comprehensive initiatives.

To help provide more centralization and a holistic culture, Voya created the Continuous Improvement Center. As a testament to its importance, the CEO of Voya led the initiative.

Keep in mind that continuous improvement is a strategy for creating better processes across an organization. And yes, this means that the effort is ongoing. There is never a true end state.

But to allow for continuous improvement, there must be a focus on transparency, quality results, and efficiency (a majority of the employees at Voya have training for this). What’s more, there needs to be tracking of the overall progress, such as with employee engagement, customer scores, and turnover rates. And for Voya, the ultimate goal was to find ways to better serve the customer.

Since early 2017, the Retirement Recordkeeping Operations group has seen a 20% reduction in not-in-good-order (NIGO) applications. There were also 41% fewer escalations on hardship calls to the call center and 54% fewer were failing internal quality control checks.1

The program has been the source of much innovation. For example, it helped with the creation of myOrangeMoney, which is an online interactive web site to help with understanding retirement savings. In a survey, there was an 80% satisfaction rate.

“Spending time with the culture and continuous improvement,” said Jeff Machols, who is the VP of the Continuous Improvement Center for Voya Financial, “was critical in our journey with RPA. This started in early 2018 when we selected and implemented UiPath. RPA was really a natural fit with our evolution. The technology was also right for us since it did not require as much integration with our IT environment.”2

But for Machols, he sees this as much more than just about technology. “Technology will not be useful unless the people understand why it’s important and how it can get results,” he said.

Such process initiatives like continuous improvement are common nowadays. However, they are usually referred to something like lean, Six Sigma, or lean Six Sigma. For the most part, these approaches can be quite useful when looking at RPA.

In this chapter, we’ll take a high-level view of these.

Lean

In 1913, Henry Ford changed capitalism in a very big way. He introduced the moving assembly line of production, which meant that a vehicle could be made within hours not days or even months. Because of this, Ford Motor would become one of the world’s most valuable companies.

But there were inherent problems with the system. It tended to be monolithic and treated workers as mere cogs. Such issues would eventually become existential problems for not only the US auto industry but many other industries during the 1970s and 1980s when foreign competition got more intense.

Of course, the main catalyst for all this was Toyota, which rethought the approach to manufacturing. In 1950, one of the family members of the company’s founders, Eiji Toyoda, actually visited a Ford plant. While he was impressed with it, he realized that mass production was not viable in Japan because the country was much smaller and the customer needs were diverse. So he led an effort to come up with the so-called Toyota production system, which would allow for a seemingly magic combination of low costs, high quality, and mass customization.

But interestingly enough, in the early years, Toyota got scant attention. The company was considered a marginal player in the massive auto market and its vehicles were really substandard. But year after year, the focus on continuous improvement was leading to quality, low-cost vehicles. The irony is that US auto companies would eventually scramble to catch up and look to Toyota for guidance on how to build better cars!

For the most part, Toyota’s approach was an amalgam of other process methods that would emerge. One of the most notable was Total Quality Management (TQM), which was based on the research of W. Edwards Deming. His emphasis was on the use of statistics to enhance quality. But Deming had a tough time getting the interest of US companies. Instead, he went to Japan where there was a much warmer reception.

Next, there was the development of lean. Jim Womack, an MIT Ph.D. and consultant, coined the term in the 1980s.

Value: For lean, value is what the customer believes is important – that is, something he or she will pay for. But this is not always obvious to determine. This is why there should be consideration of market trends and changes in tastes. There should also be a deep look at customer feedback.

The Value Stream: Once you understand the customer value, you can then map it across development, production, and distribution. Along this process, the focus is on finding ways to eliminate the waste. Essentially, these are any factors that reduce value, such as long wait times, quality issues, and high transportation costs. Yet there is some waste that is necessary, such as in the case of meeting regulatory requirements or ensuring the safety of a dangerous process.

Flow: Even if a product or service has value to the customer and has minimal waste, there still needs to be ways to make sure there is efficient creation and delivery. To do this, you can break down the process into small steps and find ways to optimize them. This also needs to be pervasive across the organization. If a process is only for one department, then its usefulness may be negligible.

Pull: Inventory can often be the biggest source of waste. It’s expensive and can be a drain on the attention of the organization. With pull, the approach is to produce quantities when needed, in a just-in-time framework. And for this to work, there needs to be a strong understanding of the customer value.

Perfection: This is considered the most important step. This involves the constant pursuit of continuous improvement, which should be the goal of every employee (this comes from the Japanese word kaizen). Employees must be empowered to take actions to pursue continuous improvement.

To get started with lean, there needs to be an understanding that it requires a change in mindset. It’s really about looking to the long term, not quick fixes. The reason is that there needs to be a true change in the culture of the company.

But as with anything new, a good approach is to take a first look at one problem to solve. This will allow for a learning experience. Then as the team gets more familiar with lean, there can be more ambitious projects to take on.

Moreover, communication is absolutely critical. To this end, you can use a software platform like Slack, Asana, or SmartSheet, which provides collaboration and tracking. They also do not require the training for traditional project management.

“It’s simple but there must be clarity of objectives and plans,” said Dave King, who is the Chief Marketing Officer at Asana.3 “But such things can get lost in an organization. It’s common for employees to not know the main goals. But with a product like Asana, everyone can be on the same page, which means a company is more agile. And yes, we have seen great results within our own organization. For example, we have several hundred community events every year and each requires 115 tasks. Without a template to track and automate the process, we would not be able to have so many events.”

Lean can be kind of fuzzy, with many variations and methods. It’s actually common for a company to create its own version, which fits its unique needs.

A famous illustration of this is Danaher. The company got its start in 1969 as a real estate investment trust. But its founders, Mitchell Rales and Steven Rales, would eventually transition out of this business and use the company as a vehicle for acquisitions.

It began with the merger of Jacobs Manufacturing with Chicago Pneumatic, to form a company that manufactured brakes for diesel trucks and power tools and industrial equipment. However, the company was under much pressure and was even headed for bankruptcy. The Rales brothers realized they had to do something dramatic – and very quick. So they sought out the help of two Toyota production experts, who inspected the factory. As should be no surprise, the Rales brothers got an earful. The bottom line: the factory was an absolute mess.

But the Toyota experts knew it could be saved, so long as there was a complete rethinking of the processes. For example, one change was to go from a clockwork to counterclockwork assembly. Keep in mind that – on average – a person’s right arm is 3 percent stronger, which translates into higher productivity! There were also a myriad of other lean processes to provide for continuous improvement.

All in all, the results were standout. Danaher would then use the learnings to create its own methodology, called the Danaher Business System (DBS). The company summed it up as “DBS engine drives the company through a never-ending cycle of change and improvement: exceptional PEOPLE develop outstanding PLANS and execute them using world-class tools to construct sustainable PROCESSES, resulting in superior PERFORMANCE. Superior performance and high expectations attract exceptional people, who continue the cycle. Guiding all efforts is a simple philosophy rooted in four customer-facing priorities: Quality, Delivery, Cost, and Innovation.”4

To support this, Danaher established kaizen sessions and policy deployment reviews (these are extensive meetings to review the progress on goals) across all the divisions. Every day, the question to ask was: “How can things be made better?”

As a testament to the priority of DBS, the CEO and executives would teach courses about lean for two weeks out of each year. In fact, the former CEO, Larry Culp, wrote daily commentary on the company intranet about the kaizens. He would also lead an annual conference to go over the best practices.5

So what has been the impact? It’s been stunning. Since the first acquisition in 1986, Danaher’s market value went from $400 million to $97 billion (this does not include the $23 billion value of the other part of the business, Fortive, that was spun off in 2016).

Six Sigma

Some of the core concepts of Six Sigma go back about 100 years, with the usage of statistical approaches for manufacturing. But it was during the mid-1980s that Motorola set out to better formalize the methods and also add its own. As the company showed notable improvements (the initial focus was on its pocket pager business), the use of Six Sigma began to gain much popularity. However, it was GE CEO Jack Welch who became the most high-profile advocate. He once noted: “Six Sigma is a quality program that, when all is said and done, improves your customer’s experience, lowers your costs, and builds better leaders.”6

For the most part, Six Sigma was about looking at disciplined ways to greatly improve quality by detecting defects, understanding their causes, and improving the processes. All this would have to be repeatable and sustainable – and yes, based on data.

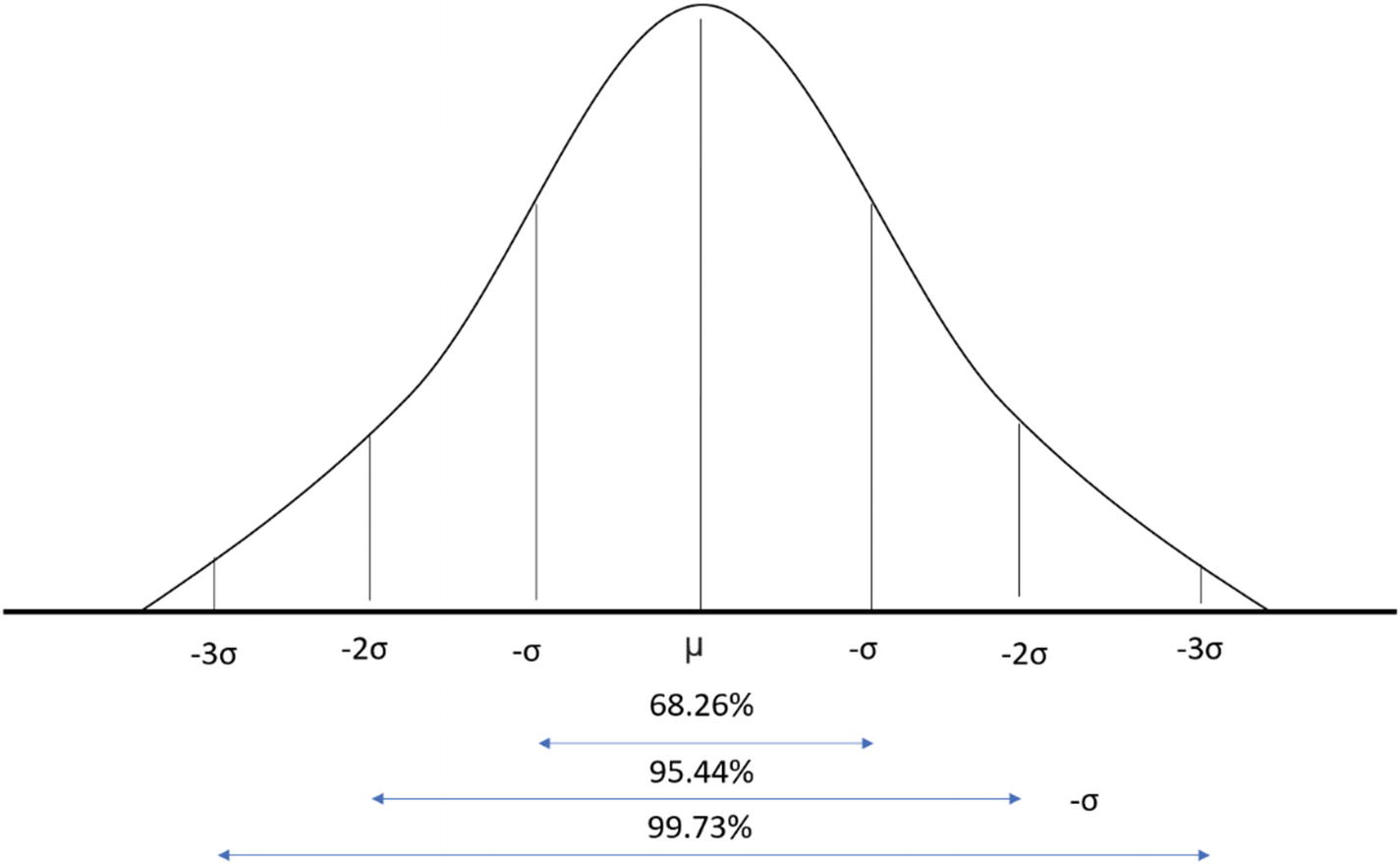

This is a chart of Six Sigma, which shows six standard deviations from the mean

To understand this, let’s get a short backgrounder on statistics. Figure 3-1 is a normal curve or a bell curve. It represents the sum of probabilities of data in a sample population and the midpoint represents the average or mean.

In the natural world, the normal curve actually reflects much of what happens, such as with height and weight. Thus, if the data is within the first standard deviation, then the data will fall within 68.26% of the total, and so on.

When it comes to Six Sigma, the normal curve means that if a process is within six standard deviations, then the process has minor defects. This is at 3.4 defects per million opportunities (DPOM). In other words, it is virtually nothing. But of course, it is extremely tough to attain this level. For many processes, it is 3 to 4 sigmas. By using techniques of Six Sigma, the focus is on finding ways to improve on the DPOM.

When doing this, there needs to be a way of measuring different processes, to get a sense of the progress. One way of doing this is using defects per opportunity (DPO), which is calculated as follows:

Total number of defects/total number of defect opportunities

Let’s take an example. Suppose we are looking at two processes in a car company. One is the attachment of mirrors, which involves 20 steps. Then there is a much more complex process – for building an engine – that has 1,000 steps.

To deal with this, we can use the DPO calculation.

Mirrors:

5,000 / (20 X 5,000) = 0.05

This means there are 50,000 defects per one million.

Engines:

5,000 / (1,000 X 5,000) = 0.001

In this case, there is a much better result, with a mere 1,000 defects per million.

Six Sigma Levels

Sigma Level | DPMO | % Good |

|---|---|---|

1 | 690,000 | 31.000% |

2 | 308,537 | 69.1463% |

3 | 66,807 | 93.3193% |

4 | 6,210 | 99.379% |

5 | 233 | 99.9767% |

6 | 3.4 | 99.99966% |

Table 3-1. This shows how Six Sigma can improve on effectiveness .

While the roots of Six Sigma were with manufacturing companies, the method has proven quite adept. It has been used for a wide variety of other types of companies, both large and small. The reason is that there are always opportunities to improve processes to increase effectiveness and efficiency.

How to Implement Six Sigma

There are different approaches to apply Six Sigma to a process. But one of the main ones is DMAIC, which stands for define, measure, analyze, improve, and control (it is pronounced as duh-may-ick).

Define: You will assemble a team and come up with a name for the project. The next step will be to identify a problem to solve (such as increasing delivery time or improving customer satisfaction scores). There should also be a timeline and clear-cut milestones to achieve. To help with this, it’s a good idea to come up with a written plan, which is often referred to as a project charter.

Measure: A good place to start is to map out the process, which can be done using a flowchart. It’s also advisable to get others to review it. After this, you can put together a data plan, which shows what data to collect and how to obtain it. Of course, this process can be time-consuming – but it is important to make sure it is done right. If the data is off, so will your results.

Analyze: This is more of a subjective part of the process. That is, you want to get a sense of the root causes of the problem. What is really going on? Why is the problem really happening? You can have brainstorming sessions as well as use diagraming systems, like the fishbone diagram. Statistical techniques can also be helpful like regression (this is a way to determine the correlation with certain variables).

Improve: At this stage, you will devise solutions to the problem. But you need to be cautious as the solution may have land mines, such as unintended consequences. So there needs to be a look at error-proofing the solution and using quality control processes. A helpful method is FMEA (failure modes and effects analysis), which was initially used in the US military during World War II and was also crucial for the Apollo space program. This is about looking at all steps and trying to identify the potential failure points.

Control : Once you have the solutions, you want to make sure they remain in place. This means establishing monitoring systems as well as having ongoing reviews to find better ways to improve the processes. There is also a need to understand when change is truly needed. After all, processes have random variances that do not require action. Thus, one way to help identify where there should be change is to use a statistical process control (SPC) chart. This graph has three lines: the average, the upper line, and the lower line. These are charted over time, which should allow for a visual way to get a sense when the variances are notable and require action.

While Six Sigma can be powerful, it is certainly not for everything. There is simply not enough time and resources to do so. In other words, it is critically important to look at those processes that will have outsized impacts on the organization. At the core of this is to think about the customer – or, as is known in Six Sigma, the voice of the customer or VOC. At first, you need to think of things in the language of the customer. How is he or she viewing the problem? After this, you will translate it for your organization into something called CTQ (critical-to-quality ) requirements. These must not only be very important but also measurable, such as in wait times, quality of the product, and on-time delivery.

Yet lean as a general philosophy and strategy has still proven to be quite effective across many different types of use cases. For example, in a study from the American College of Emergency Physicians, it was found that emergency rooms that implemented lean thinking showed improved patient care quality, wait times, and the number of patients who left the waiting room.7

Six Sigma Roles and Levels

Executive: This essentially shows that there is significant buy-in, which should lead to traction. The executive will set the overall objectives and provide approvals for key actions.

Champion: The executive will select this person, who will have Six Sigma training. The champion will take on the operational management of the project, such as by providing the necessary resources and removing any roadblocks. There will also likely be a need to manage across different departments.

Process Owner: Each of the key processes should have such a person. He or she will help manage the team and make sure the project is on track. To do this, a process owner needs to have experience with statistical techniques.

White Belts: This is a novice at Six Sigma and will have taken a few hours of training, such as on the fundamentals of quality and process thinking.

Yellow Belts: This also means having a basic level knowledge of Six Sigma, covering areas like the DMAIC system, variation, and process mapping. A yellow belt may be an executive or champion.

Green Belts: This is a person who works with black belts and will help put in place Six Sigma systems. This will require training on statistics and data analysis (which can take a few months).

Black Belts: This is a full-time Six Sigma specialist who has an understanding of advanced statistics.

Master Black Belts: As the name implies, this is the highest level for Six Sigma. They will not only help with managing a project but also provide training and mentoring.

Consider that there is no organization that provides an official Six Sigma certification. Instead, there are a plethora of training options available (as a quick Google search will show!), spanning from online to classroom instruction. There are also plenty of good books on the subject, such as The Six Sigma Handbook and the Lean Six Sigma Pocket Toolbook. Although, the Council for Six Sigma Certification does provide for standards for training.

Despite all this, to have a successful Six Sigma implementation, you do not necessarily need the different belts. Instead, the key to success is making sure the team understands the main principles of the approach.

Finally, there are software packages that can help, such as Minitab. With this, you can create charts as well as engage in hypothesis testing, compute regressions, and other statistics.

Lean Six Sigma

Because lean and Six Sigma are so powerful – and have similarities – there is something called lean Six Sigma! This is another process methodology that takes some of the best approaches of each. That is, there is the statistics and data techniques of Six Sigma as well as the focus on lean’s elimination of waste. Lean Six Sigma came about in 2001, with the publication of the book Leaning into Six Sigma: The Path to Integration of Lean Enterprise and Six Sigma by Barbara Wheat, Chuck Mills, and Mike Carnell.

Sort (Seiri in Japanese): Get clarity by taking away needless processes, clutter, and items.

Straighten (Seiton): This is about using storage and resources efficiently, such as by picking the right item at the right time. To help with this, you should organize everything in a way that makes it easy to take actions. This could actually be something like setting up an office space for maximum efficiency (not just the factory floor).

Shine (Seiso): Simply put, make sure everything is clean and tidy, which must be a daily activity. There should also be efforts to identify the root causes of dirtiness.

Standardize (Seiketsu): Come up with a step-by-step process for a clean and neat workplace, which should be backed with clear roles and responsibilities.

Sustain (Shitsuke): With the standards established, there must be ways to make sure they are upheld and maintained. This can be tough as an organization can easily lose interest in the methods.

Motion: As we saw with Danaher earlier in this chapter, the organization of a workflow can result in much wasted movement – which will lead to higher costs and more delays. When it comes to motion, there needs to be a detailed look at both the people and machines.

Transportation: This is often a major source of waste. Interestingly enough, start-ups like Lyft and Uber are based in part on dealing with this. And yes, the trucking industry has adopted different techniques and technologies to bring more efficiency. And just look at what Amazon.com has been doing with its own delivery infrastructure, which is likely to rival those of FedEx and UPS.

Defects: There are different types. A design defect is where a product has a problem because of ineffective development or testing. Then there is a manufacturing defect, which is when the problem is the result of a flaw in the assembly. And then there are defects about the elements of a product (an example is the use of asbestos in buildings that resulted in substantial liabilities). But regardless of which one, they all are something that need to be guarded against. Even a seemingly small defect can cause much trouble for a company. This is why it’s important to have strong processes in place to catch defects.

Overproduction: This waste can easily wreck a company. The toy industry is particularly vulnerable to overproduction as are apparel companies. Let’s face it, consumer tastes can change on a dime. But there are definitely ways to help with the risks. By using sophisticated software and analytics, it’s possible to get a better sense of how consumer demand is evolving. This can also be combined with just-in-time manufacturing.

Inventory: This is similar to overproduction but also includes supplies and work in progress. If too much is purchased or created, the heavier the costs. There is also the potential that the inventory will ultimately have to be written off. A company that showed how the effective management of this could turn into a superior business advantage was Dell Computer during the 1990s, which innovated the build-to-order strategy. The company would take orders directly – through the phone and eventually from the Internet – and then the PC would be quickly assembled. The suppliers would also be paid later, which would generate higher cash flows. The result was that Dell did not suffer from the heavy expenses of inventory accumulation and was able to fend off many competitors to become the top producer in the industry.

Waiting: This waste can add up quickly, whether in terms of connections with suppliers, partners, or customers. In today’s world, the expectation is that service should be as quick as possible. It’s something that has been driven by companies like Amazon.com.

Overprocessing: This is where any part of the process of the manufacturing or development is unnecessary. This could be something like creating an elegant design for an engine, even though most customers would not notice or care about them.

Once you have put in place mechanisms for lean and they begin to get results, you can then look at Six Sigma. You could start with something like kaizen or DMAIC, which we have covered earlier in this chapter.

But there are certainly a myriad of others to look at. For example, there is something known as poka yoke (this is from the Japanese words for avoid and mistakes). The goal is to create a process that has minimum errors. This could mean putting together a checklist for employees or some type of automation with a computer app, such as RPA.

Finding the Right Balance

As with anything, process methodologies can be taken to the extreme, which could lead to awful results. This is usually the case when management is mostly focused on driving steep cost cuts. True, this may get short-term results, but the moves could hamper a company’s ability to compete.

Consider the case with Kraft Heinz, which was the result of a transformative $49 billion merger that was struck in March 2015. The backing came from some of the world’s top investors, including 3G Capital Partners and Warren Buffett.

Actually, this is what Buffett had to say about the deal: “I am delighted to play a part in bringing these two winning companies and their iconic brands together. This is my kind of transaction, uniting two world-class organizations and delivering shareholder value. I’m excited by the opportunities for what this new combined organization will achieve.”8

The managers at Kraft Heinz emphasized ways to cut costs and streamline operations. And for some time, the actions worked.

But they ran too deep. The reality was that Kraft Heinz scrimped too much on R&D, marketing, and product development. Essentially, the company was being squeezed – and hard. Even worse, the consumer products market was undergoing major changes, as customers were looking for healthier offerings and lower priced alternatives to premium brands.

By February 2019, Kraft Heinz disclosed the $15.4 billion write-down of the Kraft and Oscar Mayer brands. There was also a slashing of the dividend. Since the merger, the stock price has plunged from $80 to $32.

According to business management author and professor, John Kotter, in a Harvard Business Review article: “Ultimately, leaders need to understand that the pace of change is accelerating everywhere, not just in packaged foods. In our view, Kraft Heinz’s experience shows dramatically that traditional methods of restructuring are increasingly risky. Any effort that slows down or curtails a company’s ability to innovate can lead to disastrous results.”9

Applying Lean and Six Sigma to RPA

The uses of lean, Six Sigma, and lean Six Sigma demand a major commitment of time and resources. It could easily mean delaying an RPA implementation for six months to a year. But this may ultimately be worth it. Keep in mind that many of the top IT and management consulting firms will have many Six Sigma black belts who can help redesign a company’s processes, which should go a long way in making an RPA system even more impactful.

This is not to say you need to retain such a firm (although, in the next chapter, we will cover the factors to think about this approach). There are many examples of companies that have taken a do-it-yourself approach and have been successful with it.

Regardless, there still needs to be some level of attention to current processes and standard operating procedures. The fact is that they were likely created in an ad hoc fashion, with not a lot of thought! Because of this, there should be rich opportunities to find enhancements.

But there are definitely some takeaways from lean, Six Sigma, and lean Six Sigma that can help with these preliminary actions. First of all, it’s advisable to put together some process maps, such as with a tool like Microsoft’s Visio or IBM’s Blueworks Live. The software will allow for quickly creating visualizations that will highlight the potential areas for redesign. You will also be able to invite other users to get valuable feedback.

What are the bottlenecks and root causes? What can be done to improve them?

Think about the core ideas of FMEA. So before making a change to the process, you need to brainstorm about the unintended consequences. Where could things go off the rails? Ultimately, you might realize that some functions are just poor candidates for automation.

Motion: Do not just use the software. Walk around the office and get a sense of the organization. Then go through the physical aspects of what an employee does at the desk. By doing all this, you should get a much better idea of where the opportunities are to improve the processes.

Implications of Automation: As people are prone to making mistakes – especially with tedious tasks – there may be safeguards put in place. This may be something like having someone review a process. However, with RPA, this step is probably not needed as the automation will carry out the process the same every time. But this is so long as there is extensive testing, validating, control, and audit of the bot before it is released into a production environment.

Authority : In a process, there are often times when there needs to be approval from a manager. This could be for allowing the issuance of a payment, say, over a certain amount. But with RPA, this process can be streamlined by use of exceptions that are built in to the system. What’s more, with emerging AI technologies, it may even be possible to create a bot that can make the decision on its own.

Once you have your process map, you will be in a much better position for your RPA implementation. But in keeping with the principles of lean and Six Sigma, it’s also important to have a focus on continuous improvement. The process map should just be the first step in a journey to keep finding more ways to improve processes.

Oh, and yes, there should also be an emphasis on: What is the best for the customer? How will the change in the process improve value?

Conclusion

Again, as noted in this chapter, you do not have to be a lean or Six Sigma expert for improving processes within your organization. But you can use some of the techniques to make improvements, which should allow for a better RPA implementation.

As for the next section, we’ll take an in-depth look at how to implement a system, which will involve planning, bot design, deployment, and monitoring.

Key Takeaways

Lean is a process methodology whose roots go back to Toyota in the 1950s. The company needed to find a unique way to produce cars that combined low costs, high quality, and mass customization. Over the years, the company experimented with different approaches, which eventually focused on continuous improvement.

It was during the 1980s that lean was coined and formalized. Some of the core principles included value (what customers will pay for), value stream (the mapping of the development, production, and distribution), flow (efficient delivery of value), pull (production that is only needed), and perfection (the pursuit of continuous improvement, which should be the goal of all employees).

For lean to have true impact, there must be a change in mindset. It’s about taking the long view of things, not just looking for quick fixes.

Six Sigma also goes back many years. But it was during the mid-1990s that it became a well-defined framework. This was because of the efforts of Motorola, which used Six Sigma to greatly improve its manufacturing processes.

Six Sigma is generally about using statistics to minimize defects. The goal is to reach near perfection – or 3.4 defects per million opportunities.

A common way to implement Six Sigma is to use a framework called DMAIC. It involves the following: Define (look at the problem to be solved), measure (map the process and create a data plan to track things), analyze (look for the root causes of the problems), improve (look for more efficient solutions but also try to make sure there are no unintended consequences), and control (this is about making sure the solutions remain in place).

In Six Sigma, the Voice of the Customer (VOC) is where you think of a problem from the perspective of the customer. This is then translated to the organization through something called CTQ (Critical-to-Quality) requirements.

Six Sigma has a various roles: Executive (this is a senior-level person who sponsors the project and sets the objectives), champion (this person has Six Sigma training and will provide operational management), and process owner (this is a person who will use more advanced Six Sigma techniques to manage a team).

Six Sigma has different levels of proficiencies described in terms of martial arts – from white belts to master black belts.

Lean Six Sigma combines the benefits of both process methodologies. With lean, you get the focus on the elimination of waste and other inefficiencies and Six Sigma helps with data and statistics. A typical approach is to first use lean and then go to Six Sigma.