4 What makes managers stumble?

The previous chapters contained an overview of what success actually is and what influences successful careers. As we have seen, dealing successfully and constructively with critical career situations plays a central role here. But what factors actually cause successful managers to stumble in their careers?

4.1 Leadership starts with leading yourself

Professional success is not attainable without being able to lead yourself and others well. Both aspects primarily have to do with being familiar with your own strengths and weaknesses, and working on yourself. Accordingly, my research for this book revealed that self-reflection is one of the most important prerequisites for pursuing a successful career.

Being able to manage yourself and others is undoubtedly one of the most difficult tasks in professional life. The worst thing is that managers are frequently not sufficiently prepared for it. The predominant belief in our education system and even in elite business schools is that leadership, meaning the conscious use and control of emotions in a professional context, is not particularly relevant for corporate success and is at best subsumed under the term “soft skills”. This belief costs many managers their health and, ultimately, even their lives, as I will endeavour to show. Most companies still do not take the topic of executive development seriously enough, especially at the top executive levels, where in many cases there are practically no options for further training. In a study entitled Ascending to the C-Suite, published by McKinsey in 2015, only 27% of 1195 board members questioned stated that their company had adequately prepared them for and supported them in their career step up to executive/board level.

To avoid any misunderstanding: I do not see managers as innocent victims of the “system”. We all have a duty to continue to develop our own skills. This is not something that can be delegated to anyone else. Even though dependencies and decision-making dynamics in the company “system” often put many managers in rather awkward and unpleasant situations they would rather avoid, it is not enough to simply continue pursuing the everyday agenda in the face of these dynamics and to lose sight of your own development. A manager must be able to make unpopular decisions time and time again. There will always be situations in which they are not permitted to communicate anything even though this would be helpful to the employees, for instance in the case of impending restructuring measures.

And yet, in our experience, managers still have plenty of room for manoeuvre, which they often fail to fully exploit. Today’s managers must really work towards becoming experts in the leadership of people and of themselves. This also means recognising themselves as the person they are – including their body, mind and soul – as their most important productive resource and getting themselves fit accordingly. It would never cross anyone’s mind to run a marathon without any experience or training. But many managers do this every day, as they are usually quite unprepared when they first take on the job of managing themselves, their employees and their companies, and this is definitely a long-distance discipline.

There is another way in which aspects of the VUCA world play an important role in an executive’s everyday life today, and more specifically in the IT sector and its growing influence over the past 20 years. Today, it is possible to make grave erroneous decisions in a much shorter period of time than would have been possible in the past.

EXAMPLE

The last financial crisis linked to US subprime mortgage loans could only occur as a result of financial products developed on the basis of a digitally networked economy.

Furthermore, the social media ensured that the mistakes made were disclosed in no time at all and led to negative public reactions, for instance in the form of shitstorms. The demands made on the professionality and moral integrity of managers have, therefore, clearly risen over recent decades. A successful manager has to be able and want to deal with such pressure. Yet managers are “only” humans, too. What are you supposed to do with the emotions triggered by this pressure?

4.2 Emotions in business

The prevailing opinion in the training of future executives is still that emotions, particularly destructive ones, do not belong on the executive floor. Executives must always convey tranquillity, serenity, optimism and aplomb. Excessive matter-of-factness is fine, but negative or even destructive emotions are not appropriate. Yet, this is not always that easy. Every human being, and this of course also includes executives, has an inner thought stream and feelings such as anger, doubt and fear. Our brains are simply made that way. They constantly try to predict and solve potential problems and to avoid possible dangers. In our work as coaches, we deal a lot with executives who not only have unwanted thoughts and emotions, but who also feel trapped by them like a fish on a hook. They either identify themselves with these thoughts and emotions or try to avoid situations that trigger them, such as new challenges.

When dealing with their own thoughts and behaviour patterns managers sometimes criticise themselves for having such negative emotions. Particularly tough managers ignore their negative emotions and try to actively desensitise themselves against situations that trigger those thoughts and feelings. In any case, destructive thoughts and feelings take up too much space with these managers. They divert cognitive energy away from other, probably more important topics. This is a common problem that is frequently reinforced through popular self-management strategies. We regularly encounter managers with recurring emotional difficulties, such as fear of decisions, fear of rejection, a constant focus on their own perceived weaknesses, or exaggerated envy, who have developed their own handmade techniques to get a grip on their problems, often unsuccessfully. There is plenty of available research illustrating how the attempt to ignore a thought or emotion reinforces it in the long-term. In one famous study conducted by a Harvard professor, Daniel Wegner, participants were asked to suppress any thoughts of a white bear. Of course, they had trouble doing this. Later, when the prohibited thought was lifted, this group unwillingly thought more frequently, longer and more intensively about the white bear than did the control group. Hence, the goal cannot be to suppress supposedly negative impulses. Instead, this energy needs to be sensibly channelled, which is also known as self-control. The ability to control oneself becomes essential, particularly under great emotional pressure, as in the critical career situations described above.

4.3 Insecure overachievers

Since the 1950s, McKinsey & Company, one of the world’s leading strategy consulting firms, has been known to employ the best graduates from the best universities, and to use performance incentives and a very formative high-performance culture to shape these young, hungry “high potentials” according to their requirements. After these young consultants are pushed to the maximum by their international projects, most of them voluntarily leave the company on good terms after three years at the latest in order to take up leading positions in the industry and then to become potential customers of their former employer. Over the past few decades, this HR strategy and its accompanying high-performance culture were adopted in the field of professional services by the majority of international companies and they are now also entering many more traditional industrial and service-based companies.

The expression which best describes McKinsey’s employee profile is the “insecure overachiever”, who is to be found in many management positions today. This type of person is well-educated, intelligent, often good-looking, mobile and highly performance-motivated. However, the moment you look behind the shiny facade, which we of course regularly do in our work, you find people who are continuously plagued by the question “Am I good enough?”

Of course, there are many kinds of people walking through life with these or similar questions occupying their minds, but this group of persons compensates for these nagging inner doubts with permanent high performance and success, not having any other available mechanism for accepting themselves in their state of imperfection, which we all effectively share. This inner pressure is an enormous career engine and leads to a very specific way of life, which focuses on work alone. As long as insecure overachievers are successful, the flywheel continues to turn. Problems generally arise when they are no longer successful and when they run out of physical resources; then they feel like “driven people”, like they are no longer in control of their inner world.

The situations in which this happens are typically marked by high pressure or insecurity. This account describes the typical effect of inner beliefs, which also constitute a risk factor, both for one’s inner mental balance and for one’s resilience. Beliefs are decisions with regard to one’s life that people have made in their childhood and internalised. Long before an employee or manager has to prove himself in the “company system”, he has developed success strategies in the “family system”. A lot of managers don’t like to think back to the time when, unlike now, they were small, weak and insecure, and feel like they are “on the couch” when the topic of their childhood crops up. And yet, it was already at this point in time that the course was set. As a child, each person already learns how best to handle the family system in order to be successful. Love and attention are the success criteria of a child. Beliefs are therefore strategies with which a child tries to obtain parental love and attention. In the corporate world, this is later known as “visibility” and “recognition”. When devising its strategy, a child can of course only fall back on its childlike logic. This is characterised by magical thinking – that is to say the belief that the child’s environment behaves as it does only in response to the child’s behaviour. Examples of magical thinking are: “I have to be obedient, so that my brother gets healthy again”, or “I have to work really hard at school, so that Mum and Dad don’t argue so much anymore”.

These childlike decisions become consolidated as coping strategies over the years, finding their equivalent in the brain in the form of neuronal stimulation patterns. This is why these strategies remain relevant into late adulthood, even though the family or professional system in which the person then manoeuvres is a completely different one.

Interestingly enough, in our work with managers we have noticed that the number of beliefs that these managers have internalised is limited. They can usually be reduced to a certain number of musts (i.e. positively formulated beliefs) and must nots (i.e. negatively formulated beliefs) (Table 4.3.1).

Table 4.3.1 Musts and must nots

Do any of these feel familiar to you?

These beliefs surface more frequently when a manager is not in his or her comfort zone – for example because he or she is encountering something new, unfamiliar, particularly thrilling or threatening. Since neuronal patterns cannot be deleted, an old belief cannot simply be erased. Instead, a new and more appropriate behaviour strategy has to be developed and practised.

It is important to understand that beliefs used to serve a positive purpose. Their intention was to protect us and guarantee access to positive affection. However, as we grow older and become adult professionals the side effects of our beliefs become more and more visible. Say you are running the belief, “If I am not good enough then I will not be loved”. In fact, this is the evergreen of all beliefs. The benefits of this belief are most probably that you care for performance and that you like to deliver good work. Most probably you have had some sort of success in your career because of this belief and you enjoy a good reputation. The downside of this belief might be that you cannot enjoy your success because in the very moment you have achieved something it becomes normal. Also, you may feel the urge for external appreciation to the degree that it might become an actual dependency. When you are not feeling it, this may stress you out and you may actually feel threatened by the situation. In Section 7.7.2, Transforming inner beliefs, I will outline how these dysfunctional beliefs can be reshaped into something more productive.

4.4 Managers as victims

EXAMPLE

When, on 23 August 2013, Steve Ballmer proclaimed that he would resign as CEO of Microsoft before the end of the year, the software giant’s share value bounced up 7% on the same day. This was a clear sign by investors that Monkeyboy, as Ballmer was also called for his extremely loud and flamboyant stage appearances, had obviously long passed his zenith as management figure of the Silicon Valley icon Microsoft – even though Ballmer had made a significant contribution. As Microsoft’s first manager he had been one of the main protagonists in its success story since 1980. Getting this kind of feedback when you step down is painful. So painful that, after a brief interim period as an executive board member, Ballmer broke off all contact with Microsoft and chose to pursue basketball instead.

During my research for this book, I asked my interview partners about the negative emotional, cognitive and physical consequences that critical career situations had had on them. The results are illustrated in Figure 4.4.1.

Figure 4.4.1 Consequences of critical career situations.

Source: Survey by Karsten Drath Dec 2015–Jan 2016.

For the purpose of simplicity, they can be subdivided into three segments:

The most frequent emotion was fear and the feeling of being a victim.

Symptoms of medium frequency ranged from sleeping disorders and despondency to increased irritability down to emotional numbness.

The symptoms in the last segment occur rarely, since their consequences are much more serious and threatening. They range from thinking about disaster scenarios over heightened alcohol consumption to suicidal thoughts.

If one compares these symptoms with the characteristic course of unfolding mental exhaustion, also colloquially known as burnout, then striking resemblances can be seen in the symptoms and their sequence, as shown clearly in the staircase illustration (Figure 4.4.2). It must also be borne in mind that the magnitude of the consequences of a particular critical career situation not only depends on the gravity and frequency of the symptoms, but also on how long they last.

43% of the managers questioned stated that the consequences of the severe setbacks, for them personally, lasted several weeks. With 28% of the study participants, the repercussions went on for six months. At least 12% of those affected maintained the symptoms over a period of one year, in nearly 7% of the cases even over several years. The frequency of suicidal thoughts among those managers, who experienced long-term repercussions from their critical career situations, was nearly 10%.

How can these figures be explained? What played a key role was the manager’s sense of being a victim of the circumstances and having no choice but to suffer. This is, of course, a distorted view of reality, as there are always options. Yet, in the context of difficult career situations, this victim mentality is almost always present. When this is the case, it is extremely difficult to get a manager to think more constructively.

The background is a phenomenon known as secondary morbid gain in the field of medicine. Imagine a child has a cold and a high temperature. Normally both parents work, but now one of them has to stay at home to look after the child. The child is given hot soup in bed and stories are read to it. It is allowed to eat ice-cream and watch television as much as it wants. The symptoms of the illness are unpleasant but the loving attention it gets from its parents and the luxury of suspended rules are superb. The child enjoys this so much that the illness is subconsciously prolonged for another two days in order to enjoy this secondary morbid gain a bit longer. But what morbid gain can the manager draw from his or her victim mentality? There are various aspects:

Blame: As long as the manager is in martyr mode he cannot be blamed, because he was pushed into his misery by others. Good and evil are clearly defined.

Entitlement: She is emotionally in the right and morally superior to her adversary. She is entitled to solidarity and support from other people.

Responsibility: He is not responsible for the events because he could not have done anything in that situation. His hands were tied.

Sympathy: If one is subjected to something unpleasant, one can expect to get support and sympathy from others.

Carte blanche: Someone who has lost a lot is more likely to get away with misconduct and negligence, since allowances must be made for them.

So, there are a number of good reasons for critically examining ourselves when we perceive ourselves in the role of the victim. But this is easier said than done, as our brains are so bombarded with adrenaline and noradrenaline during these stressful situations that, from a cognitive point of view, we revert back to our most primitive instincts. This is due to rather unhelpful thought patterns which we need to recognise and correct.

4.5 Watch out, thinking trap!

At the beginning of 2017, I was on my way to a prestigious leadership symposium held by a large car manufacturer. For the following two days, I was supposed to be one of the experts facilitating workshops for the 80 or so participating managers. The topic of my workshop was called “Resilience and Leadership” and I was very much looking forward to it. I had just completed the manuscript of my new book called The Art of Self-Leadership. It was my eighth book on the topic and I really think of myself as an expert when it comes to dealing with adversity and hardships – at least in theory. As it was early February there had been a very cold period with snow and ice in the past few days. However, this very morning sudden rain had turned the steps in front of my house into an ice rink and despite my wife’s warning the blessings of gravity hit me by surprise and I fell hard on my back. The pain was remarkable but I quickly got back on my feet and since I was running late I somehow got my luggage and myself into the car and drove to the venue of the event without much further ado. At this moment, I was not thinking very much. There was only one voice in my head, saying, “You have to get there somehow and you must not be late.” I don’t recall exactly how I got out of the car since I could barely walk. When I arrived at the conference the organisers looked at me with deep concern in their faces, indicating that I looked exactly as bad as I felt. They asked me if I wanted to cancel the workshops. I briefly considered it, but it just did not feel right. From previous experience, I knew that a bruised rib is a painful but a relatively hazard-free medical condition. However, I was also aware that a broken rib feels exactly the same way but with a substantially higher degree of risk associated with it, due to possible punctures of your intestines. Not a very funny thought. I recall that I heard two voices in my head. Number one felt like it was coming from an older part of my brain as it was very loud and was going something like:

Don’t be a wimp. You can’t let the client down!

They will hate you and will certainly not come back to you!

However, there was also another, yet much weaker voice which was probably coming from a more rational part of my neocortex. It was mumbling something like:

You are a flipping resilience expert. You have to be a role model for showing your boundaries. Don’t repeat your past mistakes!

Needless to say, I delivered the workshop of the first day with the help of a lot of painkillers and my usual endurance. Somehow, I survived it but I really felt that the participants had only gotten about 50% of my normal performance. However, in contrast to say ten years ago, I did not feel guilty for that. I had given it my best. Also, I had made it transparent to the managers that there had been an accident and that I might have to stop the workshop should my condition go south. Nevertheless, I felt somehow stupid for toughing it out.

In our workshops on resilient leadership my colleagues and I talk about the difference of being truly resilient as opposed to being just hard on yourself, which we will see in Section 6.3, Resilient or tough? The difference here is self-awareness. When you are just disciplined without listening to your own needs this makes you tough. This applies to many managers we work with, including my former self. The problem with exclusively focusing on toughness and denying your vulnerability is that one fine day something will come along that is tougher than you. And then this hits you by surprise and you are very likely to have no strategies to cope with this. In contrast, being self-aware means listening to your own needs and accepting your own vulnerability. However, you are still on your own when you make your decision whether to continue or not. This is what we call ambivalence. And while both options may not feel great, at least you are making a conscious decision as opposed to just acting out some unconscious drivers–like “I will be rejected if I don’t show everybody how committed I am!”–which date way back to your childhood days.

On the morning of the next day I felt much better. The pain was OK and also my mirror image resembled more the memory of my own face on a good day. This time the workshop went much smoother with great participant interaction and good feedback. I was grateful and felt a great degree of relief. Everything was geared up for a happy end and I was sure this would be a nice story on resilience to tell in my workshops to come. But “it ain’t over till it’s over”, as they say. So, I travelled on to the next town and the next hotel to run yet another workshop on resilience the next day. What an irony! I still felt as if I had been run over by a truck. And then things turned really sour. In the middle of the night I woke up with the most intense pain in my back and my chest. Luckily, I had never encountered anything as painful as that before. This time there was no doubt that it was a bit more serious. One hour later I was hospitalised and my X-ray showed a nice fracture in my ribs. I had to cancel the workshop and this time I did not feel any ambivalence. There were no longer two voices in my head trying to influence my actions. The only voice I heard was my own screaming “uhhhh” and “arggghh” whenever I made a wrong move or just took a breath a tiny bit too deep. In a bizarre way, the strong physical pain was a relief for my decision process with regards to going on or giving in. It basically relieved me of having to make the decision. I had to stay another three days in hospital until the medication and my body started to cooperate and I could walk straight again. A lot of quality time for reflection.

When executives experience difficult, even traumatic situations, such as severe health conditions or political struggles, depending on their personality structures they may be particularly susceptible to so-called thinking traps. These are dysfunctional cognitive patterns that can frequently be observed when a person is subjected to great pressure. The following are the most common thinking traps.

Thinking in disaster scenarios

The person concerned turns the solvable problem into an insurmountable crisis by means of distortion and exaggeration.

EXAMPLE

“I will lose my job and not find a new one. We will have to sell the house. I won’t be able to pay for my children’s studies, and so they will end up despising me. I will be a nobody and sooner or later my wife will leave me.”

Generalisation

To standardise the undifferentiated view of the problem, as– without exception – this situation was always that way and will always remain that way, without any chance of improvement.

EXAMPLE

“I’m simply not born to be a manager. Right from the start, I was the wrong choice for the job, I just did not realise this. The truth is I don’t have what it takes. It takes a different type of person to do the job.”

Maximising the negative, minimising the positive

Once old self-doubts have been triggered during a career crisis, they tend to take control. All of a sudden, previous successes fade into the background and only failures are remembered.

EXAMPLE

“Failed again! My father was right after all that nothing decent would ever become of me. Last year’s salary increase, the high-potential programme and the extraordinary praise I received from my boss two years ago mean nothing now. As we can see now, all that was worthless. The truth is, I’m not up to it.”

Reading thoughts

People with a chip on their shoulder tend, irrationally, to take everything personally.

EXAMPLE

“My associates are so nice to me. And my colleagues whisper and laugh behind my back in the coffee corner. Even my secretary gives me knowing looks. No doubt, everyone already knows that I’ve been fired. Who knows, perhaps they’re even behind it and ran me down to my boss.”

Emotional reasoning

Under great pressure, emotions and cognitive thinking become blurred. Our actions and decisions tend to be more irrational,i.e. based on emotions.

EXAMPLE

“My boss fired me. There is no rational reason for this. He just doesn’t like me. I always knew it. I hate him. He has no good qualities. I’m sure that in reality he’s a psychopath and has some kind of personality disorder.”

External locus of control

In the victim role it is difficult or even impossible to realistically gauge one’s own responsibility for events and the options available for moving forward out of one’s misery.

EXAMPLE

“This is all because of the strategy that the new board member introduced. It is complete nonsense, from beginning to end, and simply cannot work. I had no other choice but to oppose it. If they had been a bit savvier up there, I would have been appointed board member and then everything would have been fine.”

Are you familiar with any or even all of these thinking traps? Don’t worry, you’re in good company. Nevertheless, the potential for damage to be done by these cognitive distortions and generalisations is immense, as it makes a situation that is already difficult unbearable. Thinking traps are poison for the mind; they can lead us into seemingly hopeless situations. The good news is: if a manager does manage to get himself out of this emotional swamp, like the Baron of Münchhausen did, then critical career situations are usually processed well and lead to personal growth. Hence, nearly 63% of the study participants reported having consistently higher performance levels after overcoming a job crisis. Only 13% reported having a worse performance.

4.6 Managers as martyrs

These expressions are commonly used by managers: “My neck is on the line” and “I have skin in the game”. These rather martial-like sayings reflect the fact that many managers identify so strongly with their professional lives that they can no longer distinguish between their job and their life outside this role. These decision-makers almost always perceive any threat to their career as a threat to their very existence. Sometimes this identification has tragic consequences. Since companies these days are becoming increasingly transparent and the media ever faster, some of those events – though by no means all – which would probably have been dealt with more discreetly 15 years ago, go public. This includes the fate of some managers, which I would like to dwell on to illustrate how identifying too closely with one’s role as a manager can be life-threatening.

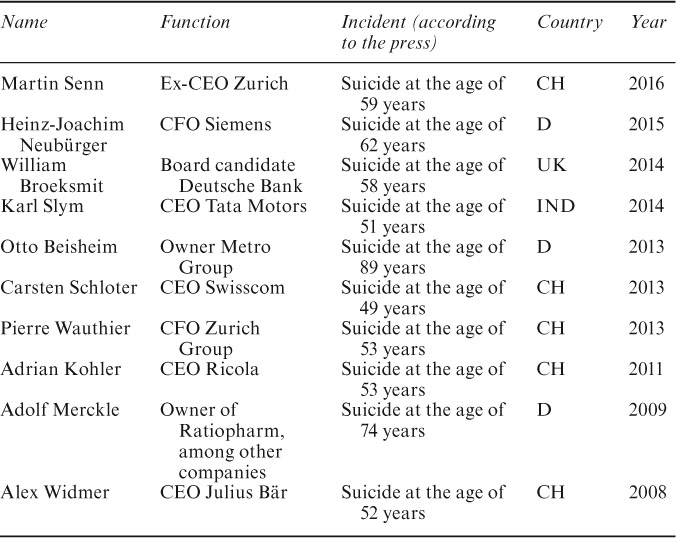

The case of Carsten Schloter, the charismatic and busy CEO of Swisscom, who committed suicide in 2013, is one of the more recent cases of a CEO suicide in the German-speaking realm. Seen merely as an isolated case, it appears extreme and very tragic. However, if we take a look at the developments of the past few years, a worrying trend can be observed among managers who evidently do not have enough resilience to withstand the increasing pressure. When confronted with tragic events like Carsten Schloter’s suicide, rationally minded people often ask themselves: “Why did he kill himself?” The example of Schloter shows that there is never just one reason or one culprit, but a whole range of factors which, combined, undermine a manager’s resilience and may eventually lead to a catastrophe, be it suicide, burnout, substance abuse or something else. Schloter was seen as charismatic, extremely hard-working, mobile and innovative. He dedicated his life to his profession and his performance. He was tough on himself, in excellent physical condition and always available. He was an exemplary manager, like many others too. But there was also another side to him. His wife and children had lived separately from him for many years already, and accounts of conflicts with the chairman of the board of directors made the rounds. In recent interviews he had admitted having difficulties finding a work–life balance and occasionally feeling driven and desperate. He was obviously not alone in having these feelings, as Table 4.6.1 shows. However, some of his manager colleagues managed to catch themselves just in time, for instance by taking time off and not allowing things to go to the extreme. Nevertheless, in all of the cases mentioned, the negative consequences on the company are clearly visible from the outside, e.g. the drop in the share price.

Another recent and equally tragic incident happened in Germany. Heinz-Joachim Neubuerger, former CFO of Siemens, enjoyed an excellent reputation throughout his career. In 1989, he had switched to Siemens from his position as head of investor relations at the investment bank JP Morgan, and he was appointed CFO nine years later. The bribery affair which came to light in November 2006 and its long-lasting and messy reappraisal were to unknowingly have major repercussions on his life. Even though he was regarded as Heinrich von Pierer’s potential successor, he was forced to resign from office after the affair became public. Yet the shock did not end there. In 2008, the company asserted claims for damages against 11 managing board members, among then Neubuerger. Several possibilities for finding an out-of-court settlement were not seized in the following years. It was only in 2014 that Siemens and Neubuerger managed to reach an amicable agreement. At the beginning of 2015, around nine years after one of the largest corruption scandals of German economic history came to light, he committed suicide.

The list in Table 4.6.1 is by no means complete and only comprises the cases mentioned in the media in German- and English-speaking countries over recent years.

Table 4.6.1 Top managers mentioned in the press in previous years because they committed suicide (selection, not definitive)

Critical career situations can have serious and even life-threatening consequences. From a psychological perspective, processing critical career situations is comparable with dealing with grief or trauma. Various models have been developed over the past few decades which could help to raise understanding of the emotional, cognitive and physical reactions.

4.7 Grieving managers

Until then, life had been in the fast lane. Everyday life under pressure, where working days were rarely less than 12 hours long and where one appointment followed the next. And then? An emergency stop! Standstill. At first there is shock, quickly followed by an unfathomable void and a sense of meaninglessness. Later, often only self-pity, helplessness and rage remain. These or similar words are the ones used by many executives to describe the moment they are informed about their dismissal, one of the worst kinds of critical career situation.

EXAMPLE

For Léo Apotheker, former CEO of the software giant SAP, it was a phone call he received one Saturday evening in February 2010, after coming out of the cinema with his wife. Hasso Plattner, founder of the company and today’s chairman of the board of directors, first discussed trivial matters with him before ending with the sentence that Apotheker’s contract as CEO would not be renewed. Apotheker had worked his way up the company over a period of 20 years. For nine months he had been at the head of the board of managers after the previous widely respected manager, Henning Kagermann, had resigned. He had been given an aggressive mandate by the supervisory board and, in implementing it, turned the entire client base and also some of the employees against himself. In response to the collapse of Lehman Brothers, he pushed through a stringent cost-cutting package and, at the same time, increased the fee for the customers’ service package. Both moves were made rather callously and without much sensitivity. Now he was fired, for the first time in his career. It was not to be the last time, but this one time will undoubtedly remain imprinted on his memory. After being dismissed, he needed three to four months to digest the shock. He expressed this to the journalist Carsten Knop in an interview. Hours after his dismissal was made public, he had received 3500 emails in which colleagues thanked him and tried to cheer him up. However, most of his colleagues and employees heaved a sigh of relief and did so openly. He withdrew into the circle of his friends and family to try to find himself again. He had many conversations to try to rid himself of his resentment. He analysed the situation and what had happened.

In hindsight, it is questionable whether he came to the right conclusions. In November 2010, much to many people’s surprise, he was appointed CEO of the hardware giant Hewlett-Packard. His predecessor had come a cropper because of an affair and the company needed some tranquillity and clarity at the top to drive forward its new direction. Here too, Apotheker managed to turn the markets, customers and employees against him within an extremely short space of time. His plans to split the corporate group led to a 45% decline in the company’s share value. Not even a year after taking on the new position, he was sacked a second time. This time he received a settlement of 7 million US dollars.

Top managers, such as Léo Apotheker, are used to turning the big wheels, leading negotiations at the highest level and constantly jet-setting around the globe. Their job is their life and serves, at the same time, as an external source to feed their own egos and sense of self-worth. They relish their influence and high standing and receive remuneration that is disproportionately high. It is obvious to everyone that they play in the premier league. But then suddenly they fall into the abyss and the fall is fast and extremely painful. As a result of the unwanted loss of their position most executives are thrown into a severe personal crisis. Cut off from the circles of power, of confidential information and critical crisis meetings, they suddenly become aware that their feeling of being irreplaceable was an illusion. Whilst they recently still attributed nearly every success story to their own performance, the new situation calls their entire self-concept into question. It is easier said than done to not retreat into your shell after experiencing such a situation but instead to see the career downturn as an opportunity for personal and professional growth. And this is exactly where resilience, or inner resistance, comes into play. The more resilient a manager is, the better he or she has learned not to regard such upheavals as a devaluation of themselves as an individual, but rather as an interesting learning experience that is just part of the “big business” game. This game is not amusing, as it is an adult game, but it still works according to the principles of a game. It has rules, even if they are not written down; there are game pieces that have their own interests; there are event cards that throw one’s own plans overboard; and there are winners and losers, who are often “thrown out” by the roll of a die.

If one examines the course of decisive career changes, it becomes clear that the individual processing steps resemble the different stages of loss, as Elisabeth Kuebler-Ross described it. The Swiss-American psychiatrist dedicated her professional life to dealing with the dying, with grief and with the processing of grief. In her book Questions and Answers on Death and Dying, she drew worldwide attention to herself back in 1971, particularly because of her model of the five stages of loss, which she developed after innumerable conversations held with the dying. She has been granted 23 honorary degrees by various universities and colleges and 70 national and international awards for her life’s work. In 1999, the news magazine TIME named her among the “100 greatest scientists and thinkers of the 20th century”.

Figure 4.7.1 shows the typical course of processing critical career situations, using the five stages of loss model with managers who had been dismissed. If this illustration reminds you of the change curve diagram frequently used in business, this is no coincidence. Kuebler-Ross’ model served as a model for this.

The summarised findings listed next originate from our work with managers in comparable situations. They are also based on the study Auf der Überholspur ausgebremst, published in 2014, a collaborative effort carried out together with the University Fresenius, the HPO Research Group, and the talent consultancy von Rundstedt.

Figure 4.7.1 The five stages of grief according to Elisabeth Kuebler-Ross.

Stage 1: Denial. A manager has successfully worked his way up to his position over the years and can proudly look back on previous successes. But recently, things have not been going so smoothly. The atmosphere is increasingly tense, he is no longer receiving the customary support from superiors, and colleagues are suddenly distancing themselves from him. The more secure a manager feels, the less he relates these harbingers to himself. Instead, he will tend to see any faulty behaviour as stemming from his counterparts and see himself as irreplaceable. Of course, nobody admits this openly. Experienced executives, who have experienced comparable upheavals and can, therefore, draw parallels and see similarities, usually recognise these signals earlier than others.

Stage 2: Aggression. Then all of a sudden comes the blow which knocks everything apart: his dismissal. This is a tremendous shock for the manager as, with the loss of his job, one of the central pillars of his life concept falls away too. Not being part of the “system” would have been inconceivable up to that point in time. The feeling of helplessness and of not being able to actively influence the situation is new to him and triggers anger and frustration. It becomes very difficult for him to think clearly and act prudently. This is further exacerbated by a sense of shame and the worry of not being able to maintain his customary living standard, as there is a reputation and a facade to keep up. Like most ousted managers, the manager concerned will tend to blame himself for not having interpreted the signs properly or taken countermeasures in time. One is always wiser with hindsight. Once the initial shock has been overcome, administrative processes ensure that the pain does not remain vague but becomes palpable. What was previously on paper, becomes more and more a reality when the office keys, key cards and business car are reclaimed and the manager becomes more and more cut off from customers, colleagues and employees. Thoughts like “Who undermined me?” or “Whom can I still trust?” often nag the departing manager.

Stage 3: Negotiation. In this stage the initial numbness and accompanying aggression gradually begin to subside. Bolstered by his customary professionalism and firm belief in success, the manager emotionally works his way back up to the top and tries to regain control. His response is: forge ahead. His ego might have taken a severe bruising, and yet, nevertheless, the manager enthusiastically goes on the search for a new and equivalent position with discipline and with the tried-and-tested strategies he knows from the past. There is an enormous need to put the current pain and shame behind him. The manager is still convinced that this is only a short downward spell and that he will quickly regain his former status. After all, he does have an impeccable network, doesn’t he? He does not allow the thought that this lean period might last a bit longer to cross his mind. The search for a new challenge is often characterised by zealous optimism. Yet, all too often, expectations are disappointed. In spite of all the efforts, the idea of “making a quick comeback” frequently turns out to be an illusion, partly fed by the manager’s conviction that previous successes are inseparably linked to his own personality and partly by a misjudgement of the labour market, which usually does not have anything nearly as attractive or promising to offer at that level.

Stage 4: Depression. In this stage, the manager is thrown back into a complexity of roles and his old self-doubts, believed to be long-forgotten. This complexity of roles is shaped by many interdependent areas of life, including the individual’s family, hobbies and social involvement. It forms the basis of a person’s sense of self-worth and identity. The more numerous the areas are, out of which this complexity of roles is shaped, the more the loss of one of these areas – such as one’s job – can be emotionally compensated for by the others. In the case of high-ranking managers, their career has, for most of their professional life, dominated and even pushed aside the other areas of life. Social contacts were often lost along the way. Other identity-shaping roles, such as the parental role or role of a best friend as a long-time companion, are increasingly pushed aside until the individual and his position ultimately merge into one.

In addition, the old, familiar self-doubts that were present in childhood, which one had always sought to conceal through career, success and reputation, come creeping back. The ensuing depression is all the more intense, the less of a role complexity there is and the stronger these self-doubts are. The old saying starts to ring true: “As soon as a fish is out of the water, it starts to smell.” Time is passing, and against the manager. Meanwhile, already half a year has passed without a new mandate. At some point he starts to consider taking on a lower-level position, but even this is not so easy.

Stage 5: Acceptance. Denial, aggression and depression have left their mark. They will accompany the manager for a long time to come. The manager still feels shame and insult when he thinks back to the preceding fall. What hurts most is the manner in which the dismissal occurred, after all that he had done for the company.

However, gradually the manager begins to realise that, in spite of all the annoyance, this difficult situation, which he would love to have been spared, still has a positive side. After some time has passed, he starts to feel less and less burdened by external expectations. New spaces open up, allowing him to thoroughly explore his own goals and values. The question of “What is it I actually want?” surfaces and is initially not that easy to answer. However, it is worthwhile giving this some thought, as this gives rise to new perspectives and opportunities.

It takes quite some time to be able to integrate your own failings into your self-image. But it is worth it. The manager will be more self-critical, think differently and question himself more as a result. He will have become tougher and more serene. By focusing on his own personal goals and values, he will ultimately manage to constructively overcome the upheaval and get off to a flying start in a new position. He has subjected his skills, values and perceptions to a critical assessment and now sees himself in a new and more realistic light. His self-image no longer depends so heavily on having a key role or position. Instead of being driven by the need to tackle each task, the focus is now on having fun on the job. In conjunction with this, the new professional position is often more closely linked to that manager’s own personal direction and brings a greater sense of satisfaction with it.

4.8 All’s well that ends well?

In the aforementioned study Auf der Überholspur ausgebremst, three-quarters of all top managers interviewed stated that, in hindsight, they enjoyed more freedom and more creative space in their new position. More than 80% claimed to have more freedom than previously. Their personal relationships improved too (nearly 90%). All study participants stated that they had at least as much joie de vivre as before the upheaval, if not more. The findings of this study are undoubtedly most informative and console the managers who are affected. Yet they should be treated with caution, as only those managers who had succeeded in achieving a new direction took part in the study. In actual fact, many top managers find it very difficult to cope with the kind of job loss outlined previously, despite all their experience, education and intelligence.

Back in 2007, the American economic scientist Jeffrey A. Sonnenfeld published the results of an analysis of 450 CEOs from listed companies who had lost their jobs. Only 35% of them returned to a position as chairman of the board of managers. 22% of them subsequently took on a consulting position. However, for a large portion of the managers (some 43%) their dismissal was the de facto end of their management career. The greater the fall from grace, the more devastating the consequences of a critical career situation will be for a manager. If we then bear in mind that managers tend to assume a large part of the responsibility (up to 50%) for the occurrence of the critical career situation themselves, as the study I carried out in preparation for this book shows, it soon becomes clear which fields of action need to be addressed.

Bibliography

Borysenko, Joan; Fried: Why You Burn Out and How to Revive; Hay House, Carlsbad, USA, 2011.

Casserley, Tim; Megginson, David; Learning from Burnout: Developing Sustainable Leaders and Avoiding Career Derailment; Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, UK, 2009.

Chandran, Rajiv et al.; Ascending to the C-Suite; McKinsey & Company, www.mckinsey.com, April 2015.

Drath, Karsten; Resilient Leadership: Beyond Myths and Misunderstandings; Taylor & Francis, Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016.

Drath, Karsten; Spielregeln des Erfolgs: Wie Fuehrungskraefte an Rueckschlaegen wachsen; Haufe, Freiburg, Germany, 2016.

Dunsch, Juergen; Nach Suiziden: Die Schweiz bewegt eine Serie tragischer Manager- Schicksale; Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Frankfurt/Main, Germany, 2013.

Freye, Saskia; Fuehrungswechsel, Die Wirtschaftselite und das End der Deutschland AG; Campus, Frankfurt/Main, Germany, 2009.

Grabe, Martin; Zeitkrankheit Burnout, Warum Menschen ausbrennen und was man dagegen tun kann; Francke, Marburg a.d. Lahn, Germany, 2005.

Haendeler, Erik; Die Geschichte der Zukunft, Sozialverhalten heute und der Wohlstand von morgen; Brendow, Moers, Germany, 2005.

Heinemann, Helen; Warum Burnout nicht vom Job kommt, Die wahren Ursachen der Volkskrankheit Nr. 1; Adeo, Asslar, Germany, 2012.

Illig, Tobias; Jammern ist gut fuers Unternehmen, Resignative Reife; manager Seminare, Bonn, Germany, 2012.

Johnson, Barry; Polarity Management: Identifying and Managing Unsolvable Problems; HRD Press, Amherst, USA, 1992.

Kowalsky, Marc; Carsten Schloter (†), Was den deutschen Topmanager in den Tod trieb; Axel Springer: Die Welt, Hamburg, Germany, 2013.

Kowitz, Dorit; Pletter, Roman; Teuwsen, Peer; Manager unter Druck, Wieder nahmen sich zwei Topmanager das Leben: Das Leben der Chefs wird haerter; Zeitverlag: Die Zeit, Hamburg, Germany, 2014.

Kuebler-Ross, Elisabeth; Questions and Answers on Death and Dying; Simon & Schuster, New York City, USA, 1972.

Kwoh, Leslie; When the CEO Burns Out, Job Fatigue Catches up to Some Executives amid Mounting Expectations; No More Forced Smiles; Wall Street Journal (Dow Jones), New York, USA, 2013.

Lawrence, Kirk; Developing Leaders in a VUCA Environment; UNC Executive Development, Chapel Hill, USA, 2013.

Mahlmann, Regina; Unternehmen in der Psychofalle, Wege hinein. Wege hinaus; Business Village, Goettingen, Germany, 2012.

Mitchell, Sandra; Komplexitaeten, Warum wir erst anfangen, die Welt zu verstehen; Suhrkamp, Frankfurt/Main, Germany, 2008.

Mourlane, Denis; Resilienz, Die unentdeckte Faehigkeit der wirklich Erfolgreichen; Business Village, Goettingen, Germany, 2013.

Nagel, Gerhard; Chefs am Limit, 5 Coaching-Wege aus Burnout und Jobkrisen; Hanser, Muenchen, Germany, 2010.

Obholzer, Anton; Zagier Roberts, Vega; The Unconscious at Work: Individual and Organizational Stress in the Human Services; Routledge, Chichester, UK, 1994.

Petrie, Nick; Future Trends in Leadership Development, A White Paper; Center for Creative Leadership, Colorado Springs, USA, 2011.

Petrie, Nick; Wake Up!, The Surprising Truth about What Drives Stress and How Leaders Build Resilience; Center for Creative Leadership, Greensboro, USA, 2013.

Reeves, Martin et al.; The Most Adaptive Companies 2012: Winning in an Age of Turbulence; Boston Consulting Group, New York, USA, 2012.

Schmid, Michael; Management by Psycho; NZZ: Format, Zuerich, Switzerland, 2013.

Snowden, David J.; Boone, Mary E.; A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making, Wise Executives Tailor Their Approach to Fit the Complexity of the Circumstances They Face; Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston, USA, 2007.

Thadeusz, Frank; Raubtiere ohne Kette; Spiegel, Hamburg, Germany, 2013.

Verfuerth, Claus; Debnar-Daumler, Sebastian; Auf der Überholspur ausgebremst; Rundstedt, Duesseldorf, Germany, 2015.

Winerman, Lea; Suppressing the ‘White Bears’: Meditation, Mindfulness and Other Tools Can Help Us Avoid Unwanted Thoughts, Says Social Psychologist Daniel Wegner; American Psychological Association, http://www.apa.org, USA, October 2011.

Wuepper, Gesche; France Télécom, Ex-Chef muss sich fuer Selbstmorde verantworten; Axel Springer: Die Welt, Hamburg, Germany, 2012.