CHAPTER

9

Foundations and Individual Shareholders Can Make a Difference

In 1993, Steve Viederman, then heading up the Jessie Smith Noyes Foundation, noticed that the foundation’s portfolio included stock with Intel. Viederman knew that one of the Noyes Foundation’s grantees, the Southwest Organizing Project (SWOP), had been trying to get information on Intel’s environmental emissions and water usage in New Mexico. The foundation gave a grant to SWOP so it could become a shareholder, and it used its shares to begin a shareholder dialog with the company. The first year, the shareholder resolution got seven percent of the vote, which allowed Noyes to commit to filing a second year. But before that happened, the company responded and gave SWOP the information it sought. Viederman was an early leader in the foundation community, understanding how to combine shareholder and grassroots power.

In 2007, the Los Angeles Times101 published a blistering investigative story showing how some of the investments of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation were increasing social problems that the foundation’s programs sought to combat. The Times found that the foundation had invested $400 million in oil companies like Royal Dutch Shell, ExxonMobil, and Chevron, which were responsible for flares blanketing the Niger Delta with pollution, causing an epidemic of bronchitis, asthma, and blurred vision in children at the same time the foundation was spending millions of dollars to improve health in the area.

The story reinvigorated the debate within the philanthropic and grantee community about whether and how foundations and their grantees should use their assets and investments to boost their philanthropic missions and partner with those they fund to organize for change. Gates Foundation CEO Patty Stonecipher said that changes in foundation investment practices would have little or no impact on social or environmental issues. Sadly, that view failed to recognize a decade of documented success with foundations supporting shareholder advocacy with organizations they fund and support, adding vision and strategy.

Another example of a highly active foundation using shareholder advocacy to advance its mission while integrating Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria across their entire investment portfolio has been the Educational Foundation of America (EFA). The foundation had long sought to promote environmental resource efficiency in its grant programs, funding activist groups on responsible forestry practices, recycling, and recycled content. The foundation realized it could use its position as an investor in major companies to press for positive change as well. EFA’s investment consultant was Thomas Van Dyck. According to John Powers, EFA board member, “Our portfolio was fully aligned with our mission and was outperforming. Engaging companies in shareholder action to complement our grant-making was a natural next step for us.” In 1995, EFA began a long partnership with As You Sow that resulted in a string of significant victories in the area of recycling and resource efficiency.

EFA’s board decided to leverage the 95 percent of its assets to improve the environmental performance of companies in its investment portfolio. “Foundations were created under the IRS tax code to leverage social change,” Powers said, “Every tool available to them should be used.”

As You Sow went to work using a strategy of developing shareholder initiatives on companies held in EFA’s investment portfolio, which, because they passed the foundation’s ESG investment screens, potentially made them more open to dialogue about improving their environmental performance. Noting the poor recycling rate for beverage bottles and cans, As You Sow program director Conrad MacKerron engaged Coca-Cola Co. to set take-back and recycled content goals for its bottles and cans. He assembled a coalition of ESG investor groups, and following several years of dialogue and shareholder votes, the company agreed to take actions that would result in collection and recycling of the equivalent of 50 percent of its bottles and cans by the end of 2015. This included a $50 million investment in what was at the time the world’s largest recycling plant for the plastic known as polyethylene terephthalate (PET) found in the hundreds of millions of beverage bottles sold every day. Working with Boston SRI firm Walden Asset Management, As You Sow later received a similar commitment from PepsiCo, to recycle 60 percent of industry bottles and cans by 2018.

EFA shares were used in successful efforts pressing Staples and Office Depot to use higher levels of recycled content in office paper sold under their names. EFA was engaged in the As You Sow effort to have Best Buy, the largest US electronics retailer, agree to an unprecedented free electronics take-back program in all 1,000 US stores starting in 2007. Because Best Buy agreed on the idea after an initial dialogue, there was no need to file a shareholder resolution. The Best Buy take-back program has been a huge success and has already recovered one billion pounds of electronics with a new goal of two billion by 2020. It is also a profit center for the company. EFA was also in partnership on successful actions by As You Sow engaging Home Depot and allies to stop selling old-growth timber and Apple Inc. to triple its electronic waste take-back programs.

Why so much success? One factor is that companies like those engaged on behalf of EFA had already passed ESG investor screens. Within such companies, corporate management is often already attuned to corporate stewardship and has incorporated sustainability goals to the point that proposals suggesting improvement are greeted more often with reasoned consideration than reflexive opposition.

Companies are often savvy enough to see how a proposed action can be a win-win-win situation by solving an environmental problem, improving customer service, and boosting sales all at the same time. In the Best Buy example cited on e-waste recycling, the company correctly surmised that by offering a convenient way for customers to drop off old computers, TVs, and cell phones, it could not just keep these materials out of landfills but also provide customers a welcome way to clean out their closets of old electronics, and drive traffic to its stores, where many stayed and shopped.

The EFA experience shows how foundations can exponentially increase the value of their program work by simultaneously funding shareholder advocacy actions in the same program areas. EFA’s actions helped lead to recycling of 20 billion bottles and cans and 500,000 tons of e-waste per year. “EFA has been a leader on so many shareholder campaigns that have made a difference,” Thomas Van Dyck said. “They came to understand the tool and to use it to create significant change.

SOMETIMES IT TAKES TENACITY

Shareholder advocates often work with multiple organizations to bring about change and broaden the platform by which a given issue can gain greater public attention. A good example is a series of shareholder resolutions filed by As You Sow on behalf of investor Cari Rudd, who later joined the board.

We met Cari through a mutual acquaintance, Lisa Renstrom, who had authorized us to file a shareholder resolution with Duke Energy on the risks of storing coal ash near their power plants. Cari and Lisa both belonged to Rachel’s Network,102 an environmental organization named after the author Rachel Carson, the scientist and environmental advocate who in 1962 wrote the groundbreaking book Silent Spring about the impact of the indiscriminate use of pesticides on the environment generally and bird populations specifically.

Cari was interested in our use of corporate engagement to bring about positive change. Rudd, a long-time environmental activist and former board chair of the Environmental Working Group, had a long history of successful advocacy for environmental and political campaigns and was an experienced investor.

For some time, we had been in dialog with Abbott Laboratories, asking them to bring a non-GMO version of their popular infant formula, Similac, to market in the United States. Even though they produced and sold it in Europe, where GMO labeling is required and people can choose what they feed themselves and their families, they insisted that it was not possible to find enough non-GMO ingredients. They also felt that there was no consumer demand, even though we pointed out to them a New York Times poll103 showing that 93 percent of people wanted GMO labeling along with numerous online petitions asking for Abbott to make non-GMO Similac.

After the dialogue had gotten nowhere, we had decided to escalate by filing a shareholder resolution, and it just so happened that Cari owned some shares of Abbott Laboratories. Within a few days, she had authorized us to file a shareholder resolution on her behalf.

“I knew I wanted to invest in responsible companies, but it never occurred to me that as a shareholder I had the power to transform corporate practices from the inside out,” Rudd shared. She had more personal reasons for wanting to be involved in this particular cause, however.

“I had used Similac with my own son when he was an infant. In fact, it was given to us in a gift basket at the hospital,” she said.

WILL MY FINANCIAL ADVISER TRY TO DISCOURAGE MY BEING AN ACTIVE SHAREHOLDER?

That was Cari Rudd’s experience. “I contacted my financial adviser and told him what we planned to do,” she said. “He did the equivalent of patting me on the head and saying, ‘Now, don’t you worry your pretty little head about that.’”

Unfortunately, this often occurs. Despite evidence to the contrary, some financial planners may believe that shareholder advocacy undermines the board of directors and may damage financial returns. Study after study has proven that this isn’t true, but the financial establishment is slow to change.

Cari needed a document indicating that she and her husband had owned the Abbott stock for at least a year, and she isn’t used to taking “no” for an answer. Since the adviser was less than helpful, she just asked his assistant for the document and got it without delay. This interaction showed her that maybe her financial advisor did not share some basic values. The bottom line is that you have a legal right to ask for and receive these documents in a timely way. If your advisor refuses or delays, you should formally complain to his/her supervisor.

CAN I SUBMIT A RESOLUTION MORE THAN ONCE?

Yes, and often it is necessary, as the Abbott initiative104 demonstrates. In order to make the process more accessible to shareholders, the SEC has established minimum vote thresholds for proxy votes. The resolution submitted on Rudd’s behalf105 was simple and straightforward, essentially asking Abbott remove GMO ingredients from their products until they were proven safe or have an interim step to clearly label the ingredients.

Given the overwhelming level of support for labeling among consumers, we felt that shareholders would be responsive. But apparently Abbott shareholders aren’t typical consumers. At their 2013 General Meeting, the resolution received just 3.2 percent of the vote. Although we were disappointed, the vote tally met the SEC threshold of 3 percent to permit the resolution to be resubmitted the following year.

Again, Rudd was the authorizing shareholder. This time, we upped the ante. In collaboration with SumofUs, an advocacy organization also working on this issue, a petition was circulated asking Abbott to market a non-GMO Similac product, or to label the one containing GMOs. The petition gathered some 70,000 signatures.

At the company’s 2014 annual general meeting, we presented the petition. Circulating the petition gave both of our organizations an effective hook to seek news coverage of the issue, and as a result, the 2014 vote was better; the resolution earned a 6.2 percent favorable vote. This was enough to open the door a crack, but in subsequent discussions with Abbott, it was clear that they were not going to act. Still, the vote met SEC threshold of 6 percent to allow the resolution to be submitted again the following year.

This felt like Groundhog Day. Rudd authorized us to submit the resolution for a third time in 2015. We knew we needed 10 percent to continue—a high bar in this case. Without proxy advisors ISS or Glass Lewis supporting it, the resolution earned only a six percent favorable vote. The low approval rate meant that we’d have to wait three years before submitting it again.

That’s a long time to wait, and, needless to say, our team and Rudd were disappointed. We examined the options available to us, but the situation didn’t look good. Dialogue had failed. A petition had failed. The resolution had not gotten the results we’d hoped for on three occasions. It looked for the moment that Abbott would get a three-year reprieve.

But, as the saying goes, when a door closes, a window opens. This window was in the executive suite of Abbott Laboratories, and I wish we had the ability to look through it, because the company’s next move came as a complete surprise to all of us.

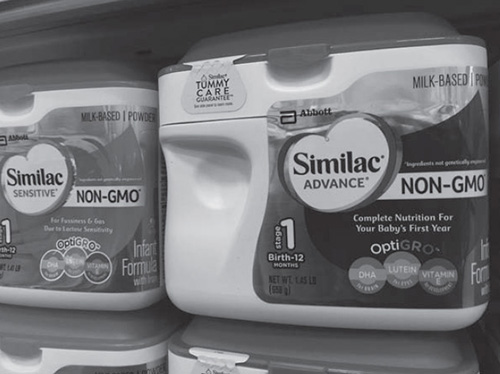

In May 2015, Abbott announced that by the end of the month they would begin selling a “Similac Advance Non-GMO Infant Formula Powder” at Target. In a New York Times106 article about the roll-out, Abbott cited consumer interest in the non-GMO products. Chris Calamari, general manager of Abbott’s pediatric nutrition business, told the newspaper: “We listen to moms and dads, and they’ve told us they want a non-GMO option.”

We were surprised and delighted by the move. The timing suggests that even as our third shareholder resolution was in play, the company was verifying the market research we had provided for them, possibly running focus groups, and finding suppliers for ingredients it would need to manufacture the product not just for a test market, as we had suggested, but nationwide at one of the country’s largest retailers.

Figure 8: Polls show 93 percent of US consumers favor GMO labeling. After three shareholder resolutions Abbott Laboratories rolled out a non-GMO Similac for the US market. Photo used with permission of the author.

The Abbott decision-making process is opaque to us. However, I can’t help but wonder whether, when Calamari told the New York Times that the company was responding to “moms and dads” who wanted a non-GMO option, he was referring to the moms and dads who participated in the polling and signed the petition we delivered at their annual general meeting.

The dialogue will continue so that shareholders can see how the market responds to the new product. We are confident that it will succeed, as within six months of the initial launch they added “Similac Advance Non-GMO Ready-to-Feed Liquid Formula,” “Similac Sensitive Non-GMO Lactose Sensitive Powder,” “Similac Go & Grow Non-GMO Toddler Drink Powder,” and other variations. We hope that soon the company will add other nutritional products, including Ensure protein and nutrition drinks and bars for seniors, and dozens of protein products for hospital tube-fed patients.

IF YOU DO NOT GET THE MINIMUM RESOLUTION VOTE IS IT STILL WORTHWHILE?

Defining success in this arena has been long debated. Ultimately, the only measure that really matters is long-term change of corporate policies and practices.

As Abbott demonstrated, you don’t need a high vote count to make change. Most votes are nonbinding, and true change happens at all vote levels. Shareholder resolutions are about bringing an idea to the public awareness, associating it with a brand, and encouraging corporate management to take action.

There are many examples of very high votes, majorities, and even near-unanimous votes that, on the one hand, were clear victories, but on the other did not affect short-term corporate policy shifts. In 2015 Royal Dutch Shell (RDS) and British Petroleum (BP) had 99 and 98 percent votes on greenhouse gas disclosure. In England, it should be noted, shareholder resolutions are binding and advocacy has a very different structure and tone. To file, a proponent needs either 100 shareholders or five percent of the outstanding shares, so resolutions are filed very infrequently. In this case a British group called “Aiming for A” built a coalition of 100+ shareholders and filed the resolutions. Management of both oil giants supported the resolutions, as they had been brought in early to have input on the drafting.

It would seem that the spirit of a 99 percent vote on climate change would have slowed Shell’s pursuit of high-risk oil, but alas, a few weeks after the annual meeting the Royal Dutch Shell Polar Pioneer arctic drilling rig headed out of Seattle Harbor through hundreds of “kayaktivists”107 engaged in the “paddle in Seattle.”108 The irony was that the rig returned shortly thereafter, and Shell’s shareholders were hit with a $7 billion loss on the venture. Hopefully the disclosure that the two companies are required to provide will reshape their thinking and actions on climate change.

DOES WITHDRAWAL EQUAL VICTORY?

There are thousands of instances where engaging directly with a company has helped educate management and led to positive changes in corporate practices. Because of this many people believe that every withdrawal of a shareholder resolution equals victory. This is simply not the case. While true progress is often made in dialogue leading to a withdrawal, sometimes this is used as a stalling tactic by the company. Further, many proponents will not withdraw a proposal so that it goes to a vote for strategic reasons. The votes at annual meetings are reported in company filings to the SEC and become part of the public record, which means the company brand is forever associated with that specific ESG issue. Sometimes the fact that a company was warned by shareholders of an impending risk can be used years later in court during litigation, especially if the board ignores the warning of risk and a calamitous event occurs that was forewarned by astute shareholders.

Such an association is often the very thing that companies seek to avoid by negotiating for a withdrawal; advocates need to be willing to stay the course if the company is not willing to commit to specific, credible, and timely progress on the given issue.

Despite the fact that Cari’s shareholder resolutions with Abbott didn’t fully achieve what she desired, Rudd is eager to move forward on other initiatives. “The process was an empowering experience,” she said. Her involvement had broader impact on her thinking about the power of shareholders, too. “In the back-and-forth of all this,” she said, “I started to think about my mother, who doesn’t have a college education and has worked very hard for an insurance company in Des Moines, Iowa, and has a 401(k). With the very modest life that she has, I kept thinking that she would feel so powerful if she could do something like this. It is an amazing avenue for just regular hardworking people.”

Even though Rudd is an experienced investor with a long track record in political causes, she didn’t really know what power she had before the shareholder resolution was filed. Discovering that power was, she said, “like you have a small garage, or a closet, and one day you find a big pry bar in there and you realize, ‘Oh, my gosh, this can really do some work.’”

Rudd felt empowered by using her leverage as an investor. “I got my wish to ‘own what I own,’” she said. “I got to understand the inner workings of how to press for change in a major global corporation as a shareholder and to witness the power shareholders and consumers have in advocating for practices that make a difference.”

IF A WITHDRAWAL RESULTS IN A REPORT THAT IS INSUFFICIENT, WHAT DO YOU DO?

The 2013 As You Sow ExxonMobil filing109 utilized shares owned by investor Martha Davis. Besides being an experienced investor, Davis was concerned about the long-term viability of her investments. However, she also had a more personal reason for getting involved in this particular action. She is a marine biologist who studies the conch, a marine gastropod native to the coasts of the Caribbean, the Florida Keys, the Bahamas, and Bermuda. She regularly travels to those areas where she and other divers conduct a census of the animals, recording their numbers, size, range, and the conditions of their habitat. In recent years, she has noticed an alarming decline in the conch population, which she attributes to overfishing and changes in the marine environment that may be linked to carbon dioxide in the atmosphere caused by the burning of fossil fuels. The ocean absorbs carbon dioxide, and as CO2 levels rise, so does the acidity of seawater, which in turn causes coral and mollusk shells to weaken.

When As You Sow’s President and Chief Counsel Danielle Fugere and Arjuna Capital’s Director of Equity Research and Shareholder Engagement Natasha Lamb sat down with the ExxonMobil negotiators, the company requested that the resolution be withdrawn.

Fugere and Lamb refused, confident that the resolution would receive a significant favorable vote if it went on the proxy ballot. ExxonMobil clearly didn’t want to take that risk if they didn’t have to. Negotiations, often very contentious, continued until finally an agreement was reached: the resolution would be withdrawn in exchange for ExxonMobil’s commitment to issue a report on Carbon Asset Risk, addressing the eleven areas of concern110 focused on exactly what the risk to shareholders was from stranded assets and how ExxonMobil intended to thrive in a carbon-constrained future.

Of course, the company could—and should—do more. But ExxonMobil’s agreement was an important first step, and it was achieved without the shareholder resolution coming to a vote. That remains in her arsenal—and ExxonMobil knows that.

Perhaps a strong vote favoring the shareholder resolution would have been more satisfying, but ExxonMobil’s agreement was significant in that it represented the first time that a major fossil fuel company had agreed to be forthcoming with their worldview about how climate change might restrict them from developing all their fossil fuel assets.

When the “Energy and Carbon—Managing the Risks”111 report was published, stating, “We are confident that none of our hydrocarbon reserves are now or will become ‘stranded,’” we sent out a press release commending the company for releasing a report, but pointed out that the data was insufficient.

The report made the New York Times112 front-page business section. The lack of disclosure sent a ripple through Wall Street and was picked up by over 400 other press outlets. So sometimes the disclosure, or lack thereof, even if not what you asked for, has profound repercussions.

FIRST THERE IS A MOUNTAIN

One ringside witness to those changes is Sanford Lewis, an attorney with over 30 years of experience in public policy–related issues, including environmental law, securities law, and public policy campaigns. He’s also a leading national expert on the filing and defense of shareholder resolutions and has been an eyewitness to their evolution.

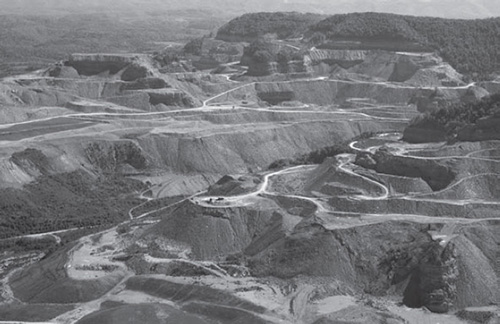

A couple of years ago, he was involved when the New York State Common Retirement Fund filed a resolution asking a company involved in coal extraction using mountaintop removal to submit disclosures about the environmental impact of their activities.

In response, the company filed what Lewis characterized as “a detailed legalistic challenge” to the proposal, asserting, in essence, that they were not engaged in the practice of mountain-top removal at all, so the proposal was not relevant to them. In support, the company submitted what Lewis characterized as a “twisted” legal definition of mountaintop removal drawn from coal mining regulations.

Lewis’s response was a document illustrated with ten pages of before-and-after photos. One picture would show a mountain. Another picture would show the same location. No mountain. At that point, Lewis said, “The SEC could not agree with them that they were not doing mountaintop removal.” In this case, Lewis successfully challenged the claim that the proposal was not relevant to the company.

Figure 9: The US Environmental Protection Agency studied more than 1,200 stream segments impacted by mountaintop mining and reported zinc, sodium, selenium, and sulfate levels in local streams. Photo used with permission of Dave Cooper, The Mountaintop Removal Roadshow.