2

NEGOTIATION

Reading and Using Body Language to Your Advantage

A few years ago, a group of rising-star executives gathered at MIT to take part in a special competitive event. Each was to present a business plan to be evaluated by the entire group. The best ideas would then be recommended to a team of venture capitalists for final evaluation. Participants saw this as a great opportunity to see how their ideas compared to those of others in an elite peer group.

If you had been one of those chosen executives, how would you have prepared for the event? Would you have concentrated on formulating a coherent description of your business plan? Developed a strategy for convincing others? Practiced your presentation skills?

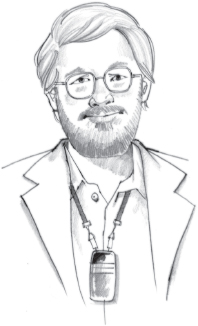

The leaders at the MIT event probably did all of these. But on the day of the competition, an additional component was added to the mix—one nobody had prepared for. Each presenter was outfitted with a specially designed digital sensor, worn like an ID badge. This device, called a Sociometer, would be taking notes on each presentation along with the rest of the group, but not on the merits of what was being said. Unbeknownst to the presenters, the Sociometer would be recording what wasn't being said: tonal variety, vocal nuance, physical activity, energy level, even the number of smiles and nods exchanged between presenter and audience.

MIT's Sociometer

At the end of the meeting, the group selected the ideas they agreed would sell best. And, with no knowledge of any actual content, the Sociometer readings also predicted (with nearly perfect accuracy) which business plans the presenters would choose. That's because, while the group thought they were making rational choices, the researchers at the MIT Media Lab, who had developed the digital device, knew better. What convinced the executive group is the same set of signals that also predict the outcome of any negotiation you may be involved in—your nonverbal signals and interactions.1

Every aspect of leadership requires some form of negotiation. Leaders negotiate salary and title before accepting a job offer; they negotiate deadlines for projects; they negotiate for funding, resources, and recognition for their departments or teams; and (depending on their specific role within the organization), they negotiate with an array of customers, clients, consultants, and suppliers. Increasingly in this interconnected business world, they also negotiate with competitors who have become allies in a current project.

Proficiency in negotiation takes good body language skills. Think of it this way: in any negotiation, you are communicating over two channels—verbal and nonverbal—resulting in two distinct conversations going on at the same time. Although a well-designed bargaining strategy is obviously important, it's not the most important message you send. Communication research shows that in a thirty-minute negotiation, two people can send over eight hundred different nonverbal signals.2 If you focus on the verbal exchange alone and ignore the nonverbal element, you stand a high chance of coming away from that negotiation wondering why in the world your brilliantly constructed bargaining plan didn't work the way it was supposed to.

Savvy negotiators have learned how to read and use body language to their advantage. This chapter will help you become aware of how nonverbal messages are being delivered and interpreted in a negotiation. It will show you how to pay attention, identify a baseline, consider the context, and evaluate gesture clusters. You will learn to accurately read your counterparts' body language and to identify how your own gestures and expressions support or sabotage your bargaining position.

FOUR TIPS FOR READING BODY LANGUAGE

When people find out that I write and speak about body language, they immediately become nervous and self-conscious. They react as if I could detect their innermost thoughts and motives with a single glance.

Well, I can't.

Neither can you. But what you can do is realize that you are “reading” people all the time without knowing it—and are prone to making the same snap decisions about others that they are making about you. You can greatly improve your accuracy by bringing awareness into what has been a mostly subconscious process. Here are four tips to help you get started.

First Tip: Pay Attention

Many negotiators miss valuable opportunities to read their counterparts' body language simply because they don't pay attention. They make the mistake of looking down at the papers or contract presented instead of staying alert to nonverbal signals. So the next time your opponent presents a written document for you to read, resist the temptation to look at it. Instead, ask him to tell you what it says, and watch his body language as he does. You'll learn so much more.

Second Tip: Identify a Baseline

To accurately read body language, you first need to establish a person's normal—or baseline—behavior. If you don't take the time to do this, you are most likely going to misinterpret his or her signals. “Baselining” entails observing people when they are not stressed or pressured. It takes only a few minutes to get a feel for how someone acts in a relaxed or neutral setting, and the best time to do this is before the negotiation starts—for instance, while having coffee and making small talk. While you are chatting informally, do a quick “body scan” and notice the following:

- How animated is your counterpart? (Does he or she show you a mobile, expressive, apparently candid face, or are you looking at the unreadable poker face of a professional card player?)

- How much eye contact are you experiencing?

- How much smiling are you being shown? Does the smile seem natural and genuine, or forced and perhaps nervous or manipulative?

- How much hand gesturing is your counterpart using? Which gestures are you seeing most frequently?

- What sort of posture is being displayed: Erect? Slouched? Shoulders back or hunched? Head held high—thrust forward—turned aside?

- When your counterpart is seated at the conference table, what position does he or she take: Upright? Leaning back? Forward? Sideways or square to the table? Legs crossed, or feet flat on the floor? Hands folded or spread on the table? Resting on or holding the chair arms? Out of sight in the lap?

Once you've determined how your counterpart uses his or her body in a relaxed, informal context, you'll have a baseline against which to compare possibly meaningful body language deviations during the negotiation process itself. (Later in the course of the meeting, whenever you see deviations from baseline behavior, think about what just happened to prompt the change. Did you alter your body language? Did you ask a question or touch on a particular issue? Did someone else enter the room or join the conversation?) For now, all you are doing is looking to identify behaviors that are normal for that person.

Third Tip: Evaluate Gestural Clusters

Nonverbal cues occur in what is called a gesture cluster—a group of movements, postures, and actions that reinforce a common point. Trying to decipher body language from a single gesture is like trying to find narrative meaning in a single word. However, when words appear in sentences, or gestures in clusters, their meaning becomes clearer. For example, although a person's fidgeting may not mean much by itself, if that person is also avoiding eye contact, wringing his hands, and pointing his feet toward the door, there's a very good chance that he's distressed and wants to leave. A good rule is to look for three body language signals that reinforce the same nonverbal message.

Fourth Tip: Consider the Context

In an audience, I expect people in the first row to be sitting with their arms crossed. I know that without a row of chairs in front of them, most people will create a barricade with their arms (at least initially, before they warm up to the speaker and lower their guard). Likewise, if a person sits in a chair that doesn't have armrests, I realize that the limited option increases the likelihood of crossed arms—as would a drop in room temperature. And if someone were deep in thought, pacing back and forth with crossed arms, I'd know that this was a common way to increase concentration and persistence. It's the same arm gesture in all situations, but the meaning changes dramatically with the context.

When people are interacting, their gender and relationship determine much of the context. The same man talking with a female colleague, his boss, or a male subordinate may display very different body language with each. (And his baseline behavior for each relationship would also change accordingly.) Such variables as time of day, expectations based on past encounters, and whether the interaction is formal or informal also need to be taken into consideration when you evaluate meaning. Of course there will always be aspects of context you won't be aware of. An erect posture may signal a tough bargaining position, or it may simply indicate a stiff back.

ARE THEY WITH YOU OR AGAINST YOU?

In a negotiation, signs of engagement and disengagement are the most important ones to monitor in the other person's body language. Engagement behaviors indicate interest, receptivity, or agreement; disengagement behaviors signal that a person is bored, angry, or defensive. And because you'll be looking for gesture clusters, you'll need to know how to identify these signals from “top to bottom” in a variety of facial expressions, head movements, hand and arm gestures, torso positions, and leg and feet placements.

This may sound like an impossible task, especially because you'll be conducting a conversation at the same time, but remember that you've been reading body language your entire life. All that is different now is that you're taking this innate but unconscious skill into awareness—and by doing so, gaining insight, accuracy, and control.

The Power of Engagement

Over the years, I've noticed that parties are more likely to reach an agreement if they begin the negotiation displaying engaged body language. Interestingly, that positive result is the same whether the display was the product of an unconscious choice or a strategic decision.

The Eyes Have It

You present two written options, and you notice that the gaze of your counterpart lingers longer on one than on the other. If, in addition, you see his eyes open wide and his pupils dilate, you know for certain that he has a much greater interest in this option.

In general, people tend to look longer and with more frequency at people or objects they like. A person may be trying to look uninterested, but his eyes will keep returning to the object that attracts him.

The same is true with eye contact. Most of us are comfortable with eye contact lasting about three seconds, and a prolonged mutual gaze without breaking can make us nervous. But when we like or agree with someone, we automatically increase the amount of time we look into his or her eyes.

Disengagement triggers the opposite gaze reactions. The amount of eye contact decreases, as we tend to look away from things that distress us and people we don't like. Similarly, a counterpart who is bored or restless may avoid eye contact by gazing past you, defocusing, looking down, glancing around the room. or even closing eyes, effectively blocking you from view. And, instead of opening wide, eyes that signal disengagement will narrow slightly. In fact, eye squints can be observed as people read contracts or proposals, and when they occur, it is almost always a sign of having seen something troubling or problematic.

Researchers have known for years that eye pupil size is a major clue in determining a person's emotional responses. The pupils are a part of our body we have practically no control over. Therefore, pupil dilation can be a very effective way to gauge someone's interest. Pupils dilate for various reasons, including memory load and cognitive difficulty, but pupils also dilate when we have positive feelings about the person we're talking to or the object we're looking at. (And when someone is less than receptive, his or her pupils will automatically constrict.)

Normal pupil size and the dilated eyes of engagement

Another set of eye cues to monitor is conjugate lateral eye movements. These are the sudden and involuntary eye shifts to the left or right which indicate that the listener is actively processing what you just said. When you notice this happening, you can be assured that you have your counterpart's interest and attention.

The Look of Business

Imagine a triangle with the base at eye level and the peak at mid-forehead. That is the most appropriate gaze area when conducting business. When you invert that triangle and drop your gaze more to the mouth, which is more appropriate in a personal relationship, you send signals of flirting.

The Head, Face, and Neck

Typically, someone who is in agreement with you will smile and nod as you speak. Disagreement shows up in compressed or pursed lips, lowered eyebrows, a tense mouth, clenched jaw muscles, head shaking, or a head turned slightly away, so eye contact becomes sidelong.

The pursed lips of disengagement

I was once asked by an SVP of human resources to work with a leader whose micromanagement was limiting her team's effectiveness. When I met with the leader, Judith, she was effusive with her praise—going on and on about how much she had heard about me and how delighted she was to have me as her coach. However, I noticed that her smiles always seemed forced. I expected to discover that she wasn't as delighted with me as she claimed and that she was putting on a show for the HR executive's sake. I was right. As time went on, it became clear that Judith had no interest in working with me (or any other coach) and no intention of changing her management style.

Smiles are often used as a polite response and to cover up other emotions, but these faked smiles involve the mouth only. Unless someone is expressing genuine pleasure or happiness, it's hard to produce a real smile—the kind that crinkles the corners of the eyes and lights up the entire face.

There are other ways that real emotions emerge, regardless of the effort to suppress them. A jump of the Adam's apple is one of these—an unconscious sign of emotional anxiety, embarrassment, or stress. You may notice this upward and downward neck movement when your male counterpart (men have a larger mass of cartilage that makes up the laryngeal prominence—Adam's apple) hears something he strongly dislikes or disagrees with.

Hands and Arms

In general, the more open the position of your counterpart's arms, the more receptive he or she will be to the negotiation process. Watch for expansive, welcoming gestures that seem to flow naturally from a person's behavior. When someone reaches toward you or uses a lot of open-hand gestures, it is usually a positive signal of interest and receptivity.

By contrast, people who are defensive or angry may protectively fold their arms across their chest, clench their hands into fists, or tightly grip their arm or wrist. Boredom is often indicated by doodling in a way that seems to absorb the doodler's complete attention, drumming fingers on the table, or using a hand to support the head. Brushing a hand across the knee or thigh, as if dusting away invisible crumbs, is a sign of being dismissive.

As the negotiation progresses, hand and arm movements are one of the best indicators of changes in the emotions of the participants. For example, when you start the negotiation, your counterpart's hands may be resting openly on the table. If they pull away or withdraw to under the table, it's probably a signal that something unsettling or unwanted just happened. And if negotiators are about to make a sincere disclosure, they will usually place both hands on the table and gesture as they speak.

Shoulders and Torso

The shoulders and torso play an important role in nonverbal communication. The more your counterparts like and agree with you, the more they will lean toward you and the more closely they will stand before or beside you. In contrast, when you say or do things your counterparts disagree with or are uncertain about, the more they will tend to lean back and create more space between you. And watch for shrugging shoulders that signal rejection in response to an idea you've just proposed.

When you see people turn their shoulders and torso away from you, you've probably lost their interest. In fact, orienting away from someone in this manner almost always conveys detachment or disengagement, regardless of the words spoken. When people are engaged, they will face you directly, “pointing” at you with their torso. However, the instant they feel uncomfortable, they will turn away—giving you “the cold shoulder.” In a negotiation, this torso shifting can occur at any time. Distressful news one minute and favorable news the next will be reflected by a torso shift toward you or away, depending on how someone feels about what was just said. And if someone is feeling defensive, you may see an attempt to shield the torso with a purse, briefcase, laptop, and so on.

People who are in agreement tend to mirror one another's behavior. One will lead and the other will follow. If you notice that your fellow negotiator has assumed the same basic body orientation as yours, move slightly and see if she follows suit. If she does, you know you've made a positive connection.

What Feet Can Tell You

At a recent conference where I was a speaker, I arrived a day early to view other presenters and to get acquainted with the audience. One of the sessions I saw was an interview with the president of a financial institution. The interviewer and interviewee were seated onstage in chairs facing the audience.

From a body language perspective, it was fascinating. At first, the executive's entire body signaled both warmth and authority as he shared his philosophy of “relationship banking” and the importance of employees to his company's brand. Then came a series of questions about executive compensation. As the bank president responded to these inquiries, his expressions and gestures stayed constant—but his “foot language” changed dramatically: from a comfortable, loose leg cross, the executive suddenly locked his ankles tightly together, pulled them back under his chair, and began to make tiny kicks with both feet. He then recrossed his ankles and kicked his feet again. This behavior continued throughout the entire set of compensation questions.

Was the executive comfortable addressing this issue? Well, his upper body would have you believe he was. And if that were all you could see (if, for instance, he had been sitting behind a desk or standing behind a lectern), you might have been convinced he was at ease. But his feet told an entirely different story—one of stress and anxiety.

Our feet and legs are not only our primary means of locomotion but also in the forefront of “fight, flight, or freeze” reactions. And they are “programmed” to respond faster than the speed of thought. Before we've had time to develop any conscious plan, our limbic brain has already made sure that, depending on the situation, our feet and legs are geared to freeze in place, run away, or kick out in defense.

When people try to control their body language, they focus primarily on facial expressions and hand and arm gestures. That leaves their feet and legs “unrehearsed.” I advise my clients to “accidentally” drop a pen during a negotiation so that they can look under the conference table and check out foot and leg positions. If someone is sitting with ankles crossed and legs stretched forward, they are probably feeling positively toward you. But when you see feet pulled away from you, wrapped in a tight ankle lock, pointed at the exit, or wrapped around the legs of a chair, you would be wise to suspect withdrawal and disengagement.

See what their feet are telling you.

The following are other signals from feet:

- High-energy heel bouncing almost always indicates that the party involved has “happy feet”—and is feeling pretty good about his bargaining position. And if your seated opponent rocks back on her heels and raises her toes, she probably thinks she has the upper hand.

- Bouncing legs that suddenly go still are probably a sign of heightened anticipation—the equivalent of holding your breath.

- Crossed legs send their own set of cues. If the foot on the leg that is crossed on top is pointing toward you, the person is most likely engaged. If the opposite leg is crossed so that the top foot is pointing away, the person may be withdrawing.

Beware of Crossed Legs

Crossed legs can have a devastating effect on a negotiation. In How to Read a Person Like a Book, authors Gerard I. Nierenberg and Henry H. Calero reported that the number of times settlements were reached increased greatly when both negotiators had uncrossed their legs. In fact, they found that out of two thousand videotaped transactions, not one resulted in a settlement when even one of the negotiators had his or her legs crossed.3

DEALING WITH THE DISENGAGED

When you notice your counterpart exhibiting any of the disengagement signals, there are six things you can do in response:

- Check your body position. Are you exhibiting any closed or disengaged behaviors that your counterpart may be mimicking or reacting to? If so, change your body language to signal more openness and warmth.

- Do nothing now, but recognize that you have hit someone's “hot button”—and use this insight as you continue to negotiate.

- Make the person move. For example, if your counterpart's arms and legs are crossed, lean forward and hand him or her something—a brochure, a contract, or a cup of coffee.

- Change your “pitch.” Realize that what you are proposing isn't being well received, and now may be the time for “Plan B.”

- Bring the person's disengagement behavior to his or her attention. The response to someone's continual fidgeting, lack of eye contact, and so on might be, “It looks as if this may be a bad time for us to talk. Would you prefer to postpone this meeting until tomorrow?”

- Watch for signals that indicate a positive change.

Many men who have their arms crossed in a defensive gesture will also have their jackets buttoned. Someone who has just favorably changed his mind might uncross his arms and instinctively unbutton his jacket.

ARE THEY BLUFFING?

Wouldn't it be great to know when someone is bluffing? And wouldn't it be nice if exposing falsehoods were as easy as it appears to be on television shows like Lie to Me and The Mentalist? But of course deception detection is more complex than that. What are often mistaken for signs of lying are actually self-pacifying gestures that everyone uses to relieve stress.

The newest technology in the field of lie detection is the use of fMRIs to track brain activity as a lie is formed. Basically, what researchers are finding is that fibbing requires more cognitive resources than being truthful. One theory, posed by Daniel Langleben, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist at the University of Pennsylvania, is that in order to tell a lie, the brain first has to stop itself from telling the truth, then create the deception, monitor to keep future statements aligned with the lie, and deal with the accompanying emotions of guilt and anxiety—this process is what the fMRIs are charting.4

But if you don't have access to an fMRI machine, how can you tell when someone is bluffing? Well, it's extremely difficult if you're dealing with a very clever liar or a superb actor. But for the vast majority of the individuals you negotiate with, the act of lying triggers a heightened stress response. And these signs are obvious, if you know where to look.

To increase your chances of spotting a bluff, watch for the following body language cues:

- Increased blink rate. Increased blinking is associated with stress and other negative emotions. So when most people are bluffing, their blink rate increases dramatically. Police interrogators and customs inspectors look for a change in the blink rate that might signify areas where the person is trying to cover something up.

- Pupil dilation. Although dilation can be triggered when we look at someone or something we are interested in, it also frequently occurs when a lie is being told. In this case, the dilation is attributed to a liar's increased tension and concentration.

- Prolonged eye contact. One body language myth to be aware of is that all bluffers will avoid looking into your eyes. Although some liars avoid or decrease eye contact, this behavior is widely known and fairly easy to control. In fact, many liars will overcompensate with too much eye contact.

- Foot movements. When trying to deceive, people will often display nervousness and anxiety through increased foot movements. Feet may fidget, shuffle, and wind around each other or around the furniture. They might stretch and curl to relieve tension, or even kick out in a sublimated flight gesture.

- Face touching. A person's nose may not grow when he tells a lie, but watch closely and you'll notice that when someone is about to lie or make an outrageous statement, he'll often unconsciously rub his nose. (This is most likely because a rush of adrenaline opens the capillaries and makes his nose itch.) Mouth touching is another gesture commonly seen in people who are feeling doubtful or being untruthful.

- Response time. When the falsehood is planned (and rehearsed), deceivers start their answers more quickly than truth-tellers. If taken by surprise, however, the liar takes longer to respond—as the process of inhibiting the truth and creating a lie takes extra time. That's why police interrogators tell me that the most common vocal deception clues are pauses that are too long or too frequent. Hesitating when responding to a question or responses that are filled with several short pauses nearly always arouse their suspicion.

- Hidden hands. Whereas open-palm gestures indicate candor, hidden hands (hands kept under the table or in pockets) may be a signal that someone has something to hide or is reluctant to participate in the conversation.

- Arrested gestures. Familiar hand, shoulder, and head gestures that seem unnaturally to be arrested midperformance can often indicate an attempt to deceive. A shrug that stops midway, a one-shoulder shrug, an incomplete hand gesture, a nod or cock of the head that seems to stop short—any of these, typically, can signal an attempt to suppress or alter information.

- Lack of nonverbal signals. When bluffing, people tend to reduce all nonverbal displays in the hope that their bodies won't “leak” the truth and expose the bluff. So be aware of the high-energy negotiator who suddenly gets much less expressive.

BODY LANGUAGE GUIDELINES FOR NEGOTIATORS

Nonverbal communication works both ways. If your counterpart is an experienced negotiator, chances are that he or she will be observing and assessing your body language from the minute you walk into the meeting room. Here are five body language guidelines to help you hold your own in the body language arena.

1. People form an opinion of you within the first seven seconds. Be aware of this and use it to your advantage.

It all begins with the right attitude. Regardless of how tiring or frustrating your day may have been, before you enter the negotiation room, pull your shoulders back, hold your head high, take a deep breath, and walk in as your “best self”—exuding ease and energy.

Just after entering the meeting room, stop for a moment and look around at the person or group that has already assembled. Open your eyes slightly larger than usual. This will trigger an “eyebrow flash” (a slight upward movement that is a universal signal of recognition and welcome). Smile.

Make eye contact with all your counterparts. A simple way to enhance positive eye contact is to make a mental note of the eye color of everyone you meet. You don't have to remember the color; just gaze long enough to notice it. With this one exercise, you will dramatically increase your likeability factor.

2. Initiate a great handshake.

The handshake—it's the most familiar and traditional of nonverbal business greetings, but hidden within such a seemingly simple formality is an opportunity to make a lasting impression. You can develop an immediate and positive connection with someone from the touching of hands.

Let's shake on it!

- Whenever possible, you should initiate the handshake. Lean forward and extend your hand with your palm facing sideways.

- Keep your body squared off to the other person—facing him or her fully.

- Maintain eye contact and continue to smile.

- Make sure you have palm-to-palm contact and that the web of your hand (the skin between your thumb and first finger) touches the web of the other person's.

- Press firmly—people will judge you as indecisive or weak if you offer a limp grip—but don't be overly aggressive and squeeze too hard.

- Hold the other person's hand a second longer than you are naturally inclined to do. This conveys additional sincerity and quite literally “holds” the other person's attention while you exchange greetings.

- Start talking before you let go: “It's great to see you” or “I'm so glad to be here.” If you are meeting for the first time, introduce yourself.

- When you break eye contact, don't look down (it's a submission signal). Rather, keep your head up and move your eyes to the side.

3. Continue building rapport.

In negotiations, rapport is the foundation for a win-win outcome. Everything you have done from the time you entered the room until now has been geared to send rapport-building nonverbal statements. To continue building rapport, remember to maintain positive eye contact, lean forward, use head nods of encouragement, and smile when appropriate.

The most powerful sign of rapport—and one that you already do (unconsciously) around people you like and respect—is to mirror the other person's body postures, gestures, expressions, breathing pattern, and so on. Mirroring builds agreement, but if you use mirroring as a technique, be subtle. Allow two or three seconds to go by before gradually changing your body language to (more or less) reflect that of the other person.

Mirroring signals liking and interest.

One executive told me that in a negotiation session, he often mirrors the person he's dealing with in order to get a better sense of what he or she is experiencing. I've noticed this as well. Our bodies and emotions are so closely linked that by assuming another person's posture, you are not only gaining rapport but actually “getting a feel” for his or her frame of mind.

Try this: when seated at a conference table across from your counterpart, push back from the table and lean away from him or her. Most probably the other negotiator will react in kind, and he or she will back away from you. (When this happens, see if the tone of the conversation also shifts to reflect the disengagement.) Now lean forward and put your hands on the table, look him or her in the eyes, and smile. Watch as the interaction warms up and is much more friendly and open. That's how fast you can build or break rapport.

4. Display confidence.

One Saturday morning a couple of years ago, I spoke at Book Passage in Corte Madera, California—a wonderful and rare example of a thriving independent bookstore. Sitting in the front row of the audience was a young woman who had seen me on a local television show and had been practicing body language to improve her confidence. She told the audience how my tips helped her buy a new car: “There I was, facing the salesman, using a ‘high-confidence’ hand gesture [the steeple position in which the palms separate slightly, fingers of both hands spread, and fingertips touch] as I stated what I wanted in the deal. The salesman countered with an arrogant body posture in which he put both hands behind his head, crossed his legs, and leaned way back. But I didn't let it faze me. I kept ‘the steeple’ pointed right at him and stuck to my guns. And, guess what—I got everything I asked for!”

You've probably seen the steeple gesture. It's a favorite of executives, physicians, lawyers, and politicians, and it conveys a sense of superiority about the issue being discussed. So if you employ that gesture, use it sparingly, and only at those moments when you need to emphasize a point. (Speakers who overuse the steepling hand gesture look stagey and insincere.)

Steepling signals confidence and certainty.

People automatically pronate their hands (rotate their palms down) when they feel strongly about something. In essence, gestures with palms exposed show a willingness to negotiate on a particular point, and palms down indicate that you are closed to negotiation. In fact, a definitive gesture of authority when you speak is to place both hands, palms down, on the table.

I'm not saying that a single gesture will get you everything you're after, but I can assure you that during any negotiation, projecting confidence is crucial. If your body language suggests that you are tentative or unsure, your counterpart may assume that you are not assertive enough to maintain your negotiation position.

There are many nonverbal signals of confidence: showing your torso is one way of demonstrating a high level of confidence, security, or trust. The more you cover your torso with folded arms, crossed legs, and so on, the more it appears that you need to protect or defend yourself. Feet also say a lot about your self-confidence. When you stand with your feet close together, you can seem timid or hesitant. But when you widen your stance, relax your knees, and center your weight in your lower body, you look more “solid” and sure of yourself.

When you need to be seen as assertive, remember that power is displayed by height and space. If you stand, you will look more powerful to those who are seated, especially if you stand with your hands on your hips. If you move around, the additional space you take up adds to that impression. If you are sitting, you can still project power by stretching your legs and arms and by spreading out your belongings on the conference table and claiming more territory. Another dominance display is to lean back with your hands behind your head and your legs in a wide-four cross. (The position that the car salesman took.) I rarely advise men to take this position—and women never cross their legs like this—because it often conveys arrogance instead of confidence.

Congruent hand gestures that supplement the points you're making can convey energy, excitement, and passion. But overgesturing with flailing arms (especially when hands are raised above the shoulders) can make you appear out of control, less believable, and less powerful.

5. Defuse a strong argument with alignment.

Often strong verbal argument comes from a negotiator's need to be heard and acknowledged. If you physically align yourself with that person (sitting or standing shoulder to shoulder facing the same direction), you will defuse the situation. And, by the way, a move that will escalate the argument is to square your body to the other person or to move in closer.

6. Make a positive final impression.

In the same way you conveyed energy and ease during your entrance and projected confidence throughout the negotiation process, be sure you also make a strong exit. Stand tall, shake hands warmly, and leave your counterpart with the impression that you are someone he or she should look forward to dealing with in the future.

![]()

In a high-stakes negotiation, as well as in everyday bargaining situations, body language skills can give you an advantage. With practice, you will be able to spot deception, to know when you have real agreement or a potential conflict, and, most of all, to feel more confident in your ability to present your thoughts and opinions with the clarity of purpose that comes only when your words and your body are saying the same thing.