1

LEADERSHIP AT A GLANCE

How People Read the Body Language of Leaders

The senior vice president of a Fortune 500 company is speaking at a leadership conference in New York. He's a polished presenter with an impressive selection of organizational “war stories” delivered with a charming, self-deprecating sense of humor. The audience likes him. They like him a lot.

Then, as he finishes his comments, he folds his arms across his chest and says, “I'm open for questions. Please, ask me anything.”

At this point, there is a noticeable shift of energy in the room—from engagement to uncertainty. The audience that was so attentive only moments ago is now somehow unable to think of anything to ask.

I was at that event. As one of the speakers scheduled to follow the executive, I was seated at a table onstage with a clear view of the entire room. And the minute I saw that single gesture, I knew exactly how the audience would react.

Later I talked with the speaker (who didn't realize he'd crossed his arms) and interviewed members of the audience (none of whom recalled the arm movement, but all of whom remembered struggling to come up with a question).

So what happened? How could a simple gesture that none of the participants were even aware of have had such a potent impact? This chapter will answer that question, first by explaining two things: (1) how the human brain processes verbal and nonverbal communication, and (2) how the early origins of body language “wired” us for certain predictable responses. As promised in the introduction, this chapter offers an expanded overview of the importance of body language to leadership success: it will explain why the key to effective body language is to view it through the eye of the beholder; it will help you evaluate your personal “curb appeal”—the first impression people have of you; it will introduce you to the two sets of nonverbal signals that followers look for in leaders. And last but not least, it will alert you to the most common mistakes people make reading your body language.

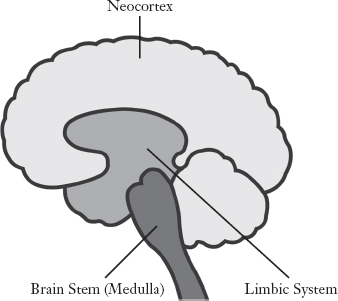

YOUR THREE BRAINS

Although neuroscience has advanced substantially in recent years, there is still controversy about the precise functions of the various brain structures. So it may be overly simplistic, but helpful, to think of the human brain is as if it were three brains: the ancient reptilian brain, the cortical brain, and the limbic brain.

The reptilian brain, the oldest of the three brain systems, consists of the brain stem and cerebellum. It controls the body's vital functions, such as heart rate, breathing, body temperature, and balance. Because the reptilian brain is primarily concerned with physical survival, it plays a crucial role in reproduction, social dominance, and establishing and defending territory. The behaviors it generates are instinctive, automatic, and highly resistant to change.

The cortical brain (with its two large cerebral hemispheres) is the newest system of the brain and the seat of our conscious thought. The prefrontal cortex acts as the “executive” for the brain. It handles such activities as language, analysis, and strategizing. We use the cortical brain when organizing our thoughts, setting goals, making plans, and solving complex problems. In the cortical system, the left brain hemisphere controls the right side of the body, and the right brain hemisphere controls the left side of the body. The hemispheres also have different specialties: the left is typically responsible for language, logic, and math; the right specializes in spatial concepts, music, visual imagery, and facial recognition. The two hemispheres communicate with one another by way of a thick band made up of nerve fibers called the corpus callosum.

The limbic brain is in the middle of the reptilian and cortical brains (both in terms of evolution and physical location). It includes the amygdala, hippocampus, cingulated gyrus, orbital frontal cortex, and insula. The limbic system, in particular the amygdala (an almond-shaped region that is located just in front of the hippocampus), is the first part of the brain to receive emotional information and react to it. As such, the amygdala acts as the “alarm system” for the brain, taking in all incoming stimuli (both physical and psychological) to decide whether or not they are threatening. It tends to become aroused in proportion to the strength of an emotional response—and the arousal to danger comes on faster and with far more intensity than the arousal to a potential reward.

In business, as in our social lives, emotions are the key drivers in decision making. Our logical processes are often only rational justifications for emotional decisions. And because most emotional decisions are made without conscious deliberation, they impact us with the immediacy and power of a limbic-brain imperative—unconsidered, unannounced, and, in most cases, impossible to resist. The limbic brain is most responsible for value judgments (often based on emotional reactions to body language cues) that strongly influence our reactions and behaviors.

It is also the limbic brain that plays the key role in nonverbal communication, in both generating and interpreting body language—a fact that explains why so many body language signals are the same around the world. An employee spots a friend, and immediately her eyebrows raise and her eyes widen in recognition; a team member reacts to distressful news by caving in his upper body and lowering his head; the winner of a conference door prize touches the base of her neck in surprise and delight; an executive's lips compress when pressured to answer an unwelcome question. All of these nonverbal limbic responses can be seen whether you are in Sao Paulo, Singapore, or San Francisco.

The triune brain

Research by John-Dylan Haynes and his team at the Center for Neuroscience in Berlin used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans to demonstrate that they could tell what test subjects were going to do as early as ten seconds before the subjects were aware that they had made up their minds. This study showed that unconscious predictive brain activity comes first, and the conscious experience follows.1

In the case of the conference speaker, although his words commanded the audience's conscious attention, his gesture spoke distinctly, but covertly, to their limbic brains. Because his words and gesture were out of alignment, the audience became confused and unsettled. And when we humans are faced with conflicting verbal and nonverbal messages, we will almost always believe and react to the nonverbal message. Why? Because we have been “wired” that way.

WIRED FOR BODY LANGUAGE

Human beings are genetically programmed to look for nonverbal cues and to quickly understand their meaning. Body language was the basis for our earliest form of communication when the split-second ability to recognize whether a person or situation was benign or dangerous was often a matter of life or death.

Of course, many aspects of body language are culturally determined. (More about this in Chapter Eight.) But whether our knowledge is innate or learned at an early age, by the time we are adults we have a full vocabulary of nonverbal signals that we instinctively read in others and automatically react to—even if they have no validity in a contemporary context.

For example: in our prehistory, it may have been vitally important to see an approaching person's hands in order to evaluate his intent. If hands were concealed, they could very well be holding a rock, a club, or other means of doing us harm. In a business meeting today, with no logical reason to do so, we still instinctively mistrust someone who keeps his hands out of sight—in his pockets, below the table, or behind his back.

The Biology of Body Language

For insight into the body language of pride and shame, scientists studied the behaviors of athletes participating in judo matches at the 2004 Olympic and Paralympic Games. The competitors represented thirty countries, including Algeria, Taiwan, Ukraine, and the United States. The research report in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences stated that body language of blind and sighted athletes showed the same patterns. The researchers' conclusion was that because congenitally blind individuals could not have learned the nonverbal aspects of pride and shame from watching others, these displays of victory or defeat are likely to be innate biological responses that have evolved over time.2

THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER

Back to our conference speaker. Why do you suppose he made such a “closed” gesture just as he was asking the audience to open up? There could have been several reasons. He might have been more comfortable standing this way. He might have been cold. The gesture might have been one he used habitually to help him think whenever questioned. Or maybe he was actually reluctant to interact with the audience.

But I never asked him that question because “why” didn't matter.

It never does.

What does matter (at least to me as a coach) is helping you understand how your expressions, gestures, eye contact, use of space, postures, and all the other aspects of nonverbal communication will most likely be interpreted by others—and how those interpretations will most likely affect the observers' behavior.

Your audience will most likely be unaware of when and how it sensed as a group that “something wasn't quite right”—or, conversely, that it could now safely place its trust in you. The decision, however, would rarely if ever have been based on a critical analysis of your statements. It would, instead, have been based on an intuitive assessment of what your audience believed you really meant by those statements (the intentions, motivations, and agenda underlying them). This information would have been communicated nonverbally and evaluated by primitive emotional reactions that have changed very little since cavemen first began grunting incoherently at one another.

This fact is crucial to the use of body language for leadership success, so let me say it again: body language is in the eye of the beholder. The impact of your nonverbal communication lies in what others believe you intend and how that perception guides their reactions.

PERSONAL CURB APPEAL

In The Political Brain, a wonderful book about the role of emotion in politics, Drew Westen talks about curb appeal. Of course, Westen is referring to personal curb appeal. According to Westen: “One of the main determinants of electoral success is simply a candidate's curb appeal. Curb appeal is the feeling voters get when they ‘drive by’ a candidate a few times on television and form an emotional impression.”3

What Westen found was that, after party affiliation, the most important predictor of how people vote is their emotional reaction (gut feeling) toward the candidate. For years now, I've been finding identical reactions in the workplace. A long time before your performance proves them right or wrong, people will have made an emotional decision about whether to follow you, trust you, or even listen to you. So the question I ask all my clients is “What is your personal curb appeal?” How do employees, team members, customers, and colleagues feel about you when they “drive by” your office a few times or observe you in the corporate hallways?

Research shows that your personal curb appeal can be assessed quickly and that many times these instant assessments are startlingly accurate. Psychologists Nalini Ambady and Robert Rosenthal conducted experiments involving what they called “thin slices of behavior.”4 These studies have been referenced in numerous writings—most famously, in Malcolm Gladwell's book Blink. In one such study, subjects watched a thirty-second clip of college teachers at the beginning of a term and rated them on such characteristics as accepting, active, competent, and confident. Analyzing this small sampling of behaviors, raters were able to accurately predict how students would evaluate those same teachers at the end of the course.

As you would suspect, thin slicing is primarily a nonverbal process. When Ambady and Rosenthal turned off the audio portion of the teachers' video clip, so that subjects had to rely only on body language cues, the accuracy of their predictions remained just as high.

The Look of Leadership

The major issue of the first televised presidential debate (in 1960) became the photogenic appeal of John F. Kennedy versus the sickly look of his opponent, Richard Nixon.

Several factors contributed to Nixon's poor image. His ill health leading up to the debate, which resulted in a drastic weight loss. His refusal to wear makeup despite the pallid complexion caused by his illness. His decision to wear a suit that blended in with the light grey color of the set's backdrop. And, probably more damaging than these, the several on-camera shots of him wiping perspiration from his forehead while Kennedy was pressing him on the issues.

Jack Kennedy, by contrast, excelled in front of the camera. A polished public speaker, he appeared young, athletic, handsome, and poised. His practice of looking at the camera when answering questions—and not at the journalists who asked them, as Nixon did—made viewers see him as someone who was talking directly to them and who gave them straight answers.

When the debate ended, a large majority of television viewers recognized Kennedy as the winner. In contrast, most radio listeners thought that Nixon had won. Obviously, appearance and body language mattered!

Never again would political debates be the same. Today's candidates are fully aware of (and heavily coached on) the impact of appearance and nonverbal cues. Today's leaders should be just as aware.

Body Language at the Debates

During the presidential debates of 2008, I was asked by the State Department to post to its Web site my observations of the candidates' nonverbal behaviors. What struck me most strongly was that both candidates made “curb appeal” errors. In most of the debates, (then) Senator Obama minimized his emotional reactions and reinforced the impression that he was cerebral, remote, and “cold,” and Senator McCain's forced grins and eye rolling in the third debate sent a negative signal that was reflected instantly in polls rating the candidates' likeability.

Warm and Authoritative Leaders

There are two sets of nonverbal signals that are especially important to the curb appeal of leaders. When first introduced to a leader, we immediately and unconsciously assess him or her for warmth and authority. Obviously the most appealing leaders are seen to encompass both qualities, and the least effective leaders are those we regard as cold and inept. But as Harvard Business School professor Teresa Amabile described in an aptly titled article, “Brilliant but Cruel,” the problem is that we often see competence and warmth as being negatively related—warm leaders don't appear as intelligent or skilled as those who are more negative and meaner, and tough leaders are judged far less likeable.5

So the best leadership strategy is to embody both sets of traits—and to do so early and often. Let people see both sides of your leadership character. Let them know right from the beginning that you are caring and credible.

The Body Language of Warmth and Authority

Always remember that people will be watching your actions as a leader. The higher you go in the organization, the more people will be scrutinizing your behavior. If you want to be a great leader, you'll need to get used to people viewing and evaluating your every move. Many executives underestimate the importance of their behavior to the people they lead. But Sue, the savvy CEO of a telecommunications company, is not one of them. As Sue says, “I know that everything I do in the hallway is more important than anything I say in the meeting.”

I've learned a lot about warmth by observing effective executives like Sue and noting how they work with their staffs. The best of these leaders connect with people in a way that makes them want to do a really good job because of that personal connection, affection, and respect. These “warm” leaders send signals of empathy, friendliness, and caring.

As a leader, you communicate warmth nonverbally with open body postures, palm-up hand gestures, a full-frontal body orientation, positive eye contact, synchronized movements, head nods, head tilts, and smiles. As you read the rest of this book (especially the chapters on negotiation, collaboration, and change management), you'll learn why these signals are so important—and when it's most effective to display them.

People also want leaders who display power, status, and confidence. Especially in times of chaos and confusion, employees look for leaders who project stability and certainty, who make them feel secure, and who they believe will achieve results. And they will assess you for these qualities through your nonverbal displays of authority.

As a leader, you show authority and power by your erect posture, command of physical space, purposeful stride (like that of Apple's CEO Steve Jobs as he moves across the stage during a presentation), and firm handshake, and through an array of hand signals including “steepling” and palm-down gestures that send nonverbal signals of authority. (Chapter Two will show you how to use these signals to your advantage in a business negotiation.)

What must be kept in mind, however, is that signals designed to project power and strength can be overdone or displayed inappropriately. For example, a nonverbal signal of confidence is to hold your head up—but if you tilt your head back even slightly, the signal changes to one of “looking down your nose.” Similarly, a smile (which is the most positive and powerful display of warmth) can, as I'm sure you can imagine, work against you if you smile too much when delivering a serious message or stating an objection.

FIVE MISTAKES PEOPLE MAKE READING YOUR BODY LANGUAGE

The ability to instantly read body language is one of our basic survival instincts and can be traced back to primitive origins. But our ancient ancestors faced daily threats and challenges very different from those we confront in today's workplace. So, as innate as this ability may be, not all instant impressions are accurate. In fact, when people read your body language, you can count on them making these five major mistakes:

- They don't consider the context. When it comes to body language, context is king. You can't make sense of someone's nonverbal message unless you understand the circumstances behind it. Context is a complex weave of variables including location, relationships, time of day, and past experience. Depending on the context, the same nonverbal signals can have totally different meanings. Take the simple shoulder shrug, for example: in a social setting, it can be a sign of flirtation; when responding to a question, it becomes a nonverbal way to say “I don't know” or “I don't care”; it can be used by a coworker to minimize the importance of what you just said; and when accompanying a workplace directive, such as “Get the report to me by Monday,” it serves to weaken the declaration.

Remember that your team members, colleagues, and staff can't possibly know all the variables that create the context of your actions. You yawn and stretch, and your staff assumes that you're bored—because no one realizes you've been up since dawn to place an overseas call. Or you hug a coworker and it looks like inappropriate behavior to passersby who don't know that her mother just died and you are comforting her.

- They find meaning in a single gesture. As the gatekeepers, confidants, and (oftentimes) fierce protectors of the leaders they support, executive assistants are asked a lot of questions. But the question they hear most often is “What mood is the boss in?”

Of course! When you are a leader, people are on constant alert to find out if you are in a good mood (happy, positive, upbeat) or a bad mood (worried, angry, upset), because your mood is their “green light-red light” signal to approach or avoid. If you are in a good mood, it means there's an opportunity for people to bring up a concern, an idea, or a request. When you are in a bad mood, people will go out of their way to avoid dealing with you.

But even when people aren't inquiring directly about your state of mind, they will still be evaluating it through your body language. And this is where trouble can arise, because all too often they will be getting their information from a single nonverbal cue. And because the human brain pays more attention to negative messages than it does to positive ones, what people unconsciously look for and react to the most are signs that you are in a bad mood and not to be approached.

What this means in a business setting is that if you pass a colleague in the hallway and don't make eye contact, she may jump to the conclusion that you are upset with the report she just turned in. Or if you frown in a staff meeting, attendees may think you didn't like what you just heard—and they will keep their corroborating opinions to themselves. In fact, when you make any nonverbal display of anger, irritability, or annoyance, people are more likely to hold back their opinions, limit their comments, and look for ways to shorten their interaction with you.

- They don't know your baseline. One of the keys to accurately reading body language is to compare someone's current nonverbal response to his or her baseline, or normal behavior. But if people haven't observed you over time, they have little basis for comparison. Here's an example from my previous book, The Nonverbal Advantage, that illustrates how easy it is to misinterpret nonverbal signals under these circumstances.6

I was giving a presentation to the CEO of a financial services company, outlining a speech I was scheduled to deliver to his leadership team the next day. And it wasn't going well.

Our meeting lasted almost an hour, and through that entire time, the CEO sat at the conference table with his arms tightly crossed. None of my efforts at small talk loosened him up. He didn't once smile or nod encouragement. So I launched directly into my remarks, and when I finished, he said thank you (without making eye contact) and left the room.

I assumed his nonverbal communication was telling me that my speaking engagement would be canceled (I'm an expert at this, after all). But when I walked to the elevator, the CEO's assistant came to tell me how impressed her boss had been with what I had to say. I was shocked, and asked how he would have reacted had he not liked it. “Oh,” said the assistant, her smile acknowledging that she had previously seen that reaction as well. “He would have gotten up in the middle of your presentation and walked out!”

The only nonverbal signals that I had received from that CEO were ones I judged to be negative. What I didn't realize was that, for this individual, this was standard operating procedure.

- They evaluate through the filter of personal biases. There is a woman in my yoga class who liked me from the moment we met. I'd prefer to believe that her positive response was a result of my charismatic body language, but I know for a fact that it's because I resemble her favorite aunt.

So sometimes biases work in your favor. The term “halo effect,” coined by psychologist E. L. Thorndike, describes how our perception of one desirable trait in a person can cause us to judge that person more positively overall.7 If we view someone as likeable, for instance, we often also perceive him or her as more honest and trustworthy as well.

I've noticed that it goes even further. Some leaders are so well liked that the people they lead forgive, overlook, or even deny negative characteristics—another example of the emotional brain overriding the analytic brain (but not so good for getting accurate performance feedback).

Biases can also work against you. What if, instead of a beloved aunt, I had reminded my yoga classmate of someone she despised? I might have overcome it with time, but you can bet that her initial response to me would have reflected that negative bias.

There is a test that's available on a Harvard University Web site—the Implicit Association Test (IAT)—that measures the extent to which individuals associate various characteristics, such as race, sexual preference, and weight, with positive or negative attributes. The test reveals that even when people consciously believe otherwise, they respond in ways that reveal their unconscious biases.8

- They evaluate through the filter of cultural biases. When it comes to dealing with a multicultural workforce, we create all sorts of obstacles by failing to consider cultural biases—theirs and ours. And when it comes to cross-cultural nonverbal communication, those biases can appear in all sorts of ways.

As a leader, you will be judged by behaviors that may include how close you stand to a colleague in conversation, how much or little you touch others, and the amount of eye contact you use (and expect in return) when meeting with a subordinate. Depending on the observer's cultural bias, your body language will be labeled “right” or “wrong.”

WHEN YOUR BODY DOESN'T MATCH YOUR WORDS

The senior vice president who addressed the conference in New York made a basic body language blunder when his gesture didn't match his words. And it is this kind of misaligned signaling that people pick up on more quickly and critically than almost any other. In fact, their brains register the incongruence in ways that can be scientifically measured.

Neuroscientist Spencer D. Kelly of Colgate University studies the effects of gestures by using an electroencephalograph (EEG) machine to measure “event-related potentials”—brain waves that form peaks and valleys. One of these valleys, dubbed N400, occurs when subjects are shown gestures that contradict what's spoken. This is the same brain-wave pattern that occurs when people listen to nonsensical language. So, in a very real way, when your words say one thing and your gestures indicate another, you don't make sense.9

Sometimes a leader's incongruent body language is so obvious that it's almost comical. Here is an e-mail sent to me from a government committee member: “I was in a very serious meeting in Washington DC and the person making the presentation was telling the group how much he welcomed any input we could provide. At the same time he was using both his hands to nonverbally push the entire group away. The amazing thing was that he repeated this sequence several times, always saying that he would welcome our input while making exactly the same ‘push back’ gesture. It was all I could do not to absolutely lose it and laugh out loud. I almost did, but that would not have been good!”

But most often a leader's incongruence is no laughing matter. Here's an e-mail from an office worker in an insurance company: “My boss drives us crazy with her mixed messages. She says things like, ‘You are always welcome in my office’ and ‘You are all an important part of the team.’ At the same time, her nonverbal communication is constantly showing how unimportant we are to her. She never makes eye contact, will shuffle papers when others talk, writes e-mail while we answer her questions and generally does not give her full attention. In fact, we don't even rate her half attention! Then she wonders why her staff doesn't seek her out.”

THE BODY LANGUAGE OF A GREAT LEADER

At some point in the coaching process, clients will usually ask (and you may be wondering too), “Does this mean I have to inhibit every spontaneous gesture and expression for fear of sending the wrong message?”

Well, yes!

Relax, I'm only joking. Successful leaders don't memorize “the right” physical gestures and facial expressions to display at appropriate times as though they were some kind of preprogrammed robot. (And, by the way, leaders who try to do this actually look like robots.) But they are aware that their body language dramatically impacts colleagues, clients, and staff. They understand that for a variety of reasons, even the most well-meaning behaviors will sometimes be misinterpreted, and they are ever alert to finding authentic ways to align their nonverbal communication with the messages they want to deliver.

The next three chapters will show you exactly how they do that.