Conciseness is Critical

This chapter is about saying what you mean without adding unnecessary details, words, or ideas. In short, it’s about conciseness.

The first step en route to writing and speaking concisely is understanding what’s meant by conciseness. The shortest government e-mail, the briefest Oscar acceptance speech, and the thinnest committee report all might, in fact, be wordy. Conciseness does not mean shortest, it means the shortest possible communication that is still complete.

So, briefly, let’s look at why conciseness is important.

Omitting information will only raise questions or lead to poor decision making. Taking out facts, qualifiers, and important context means your audience may lose the thread of what you’re saying and lose interest. Or become increasingly confused.

Conciseness is also linked to tone. Sometimes we add words to soften what we’re saying and to give readers and listeners time to absorb our message. Indeed, longer sentences are generally softer sentences. Adding words for this purpose isn’t being verbose. It’s being smart.

Now let’s look at why conciseness is an issue.

There are three steps to communicating, a reality that surprises many people. The first step is preparing, getting ready to speak or write. Making sure you have all the information you need, you’ve thought your message through, you understand your purpose. Next, for writers and presenters, comes drafting. Putting your thoughts down so you’ll be confident they flow smoothly, they make sense, they engage the audience.

Many communicators stop here. This is especially true for shorter presentations and pieces of writing. We’re in a hurry, we’re a professional, we know what we’re talking about. We don’t need to take a second look.

Yep, you do.

The final step in the communications process is editing. Looking at what you have to say and seeing how it could be said better. Conciseness plays a role here. Could words, sentences, paragraphs, examples, slides, anecdotes be shorter without losing important information or context? The answer, invariably, is yes.

It’s the old adage, think before you speak. Sometimes all it takes is a deep breath to mentally revise what you were about to say. Sometimes all it takes is a quick stretch and a second glance at that e-mail to realize you forgot to ask a question or have over-explained your request.

Finally, let’s look at why long-winded speakers and lengthy documents drive us nuts.

Length irks readers and listeners for a number of reasons. And we’ll get to them. First though, picture this. It’s Monday morning. You’ve had a great weekend—friends came over, you went for a hike, the baby slept in until 5 a.m.—but now it’s back to the office. You have two meetings scheduled for this morning and at least one deadline looming. And that’s before you’ve ordered your coffee from the drive-through.

You hustle in your office and peeking out from the corner of your desk chair is a document. You pick it up. It’s 40 pages long.

What’s your reaction?

Almost without fail, your heart will plummet, your blood pressure will rise, your stomach will churn, and whatever optimistic outlook you had for the day will disappear. All this and you haven’t even read the report yet (it could be riveting). Indeed, you haven’t even glanced at the title. Your physiological reaction is based simply on the sheer length of the document. It’s the same way when your boss schedules a two-hour meeting to discuss the holiday party or the 60-minute agenda calls for a 40-minute presentation on the new payroll software.

Several years ago I was asked to give a presentation to students at an elementary/junior high school. It was Writers’ Week, and in addition to the poets, the novelists, and the playwrights, I was asked to speak about life as a professional writer, someone who earned their living putting words to work. The audience was tweens, kids between 9 and 12 years of age.

The talks were all being held in the school library, and while we were waiting for the thud of pre-teen footsteps, the librarian took me on a tour. The library was quite new and reflected the new way of thinking about libraries—as places to spark imagination and engagement not enforce a cone of silence. The librarian had only been in her role for a few years. She told me that as a library school student she had been given a list of criteria to use when selecting material for tweens. On that list were things like this: the main character had to overcome an obstacle; all loose ends had to be tied up; good had to win out over evil.

What wasn’t on that list the librarian told me was the number one criteria for selecting material for tweens. This she learned when she left school and entered the “real world.” All the other criteria she was taught at university were still important, they just weren’t the most important.

So what do you think is the most important criteria for selecting a book for tweens?

Many people think it is the cover. Nope.

Some think it’s the title? Nope.

It’s the size of the book. Demonstrating with her hands and a great deal of laughter, the school librarian showed me what happens when a tween mistakenly pulls a large tome from a library shelf. They immediately put it back and breathe a sigh of relief. It’s like they’re saying, “Phew. That was close.”

At the point the kids shove the book back on a shelf, they haven’t glanced at the title, checked out the cover, or browsed the flip side of the book. Yet every fiber in their body is telling them to get rid of this—and quickly.

Now Harry Potter and friends may be helping to transform this almost involuntary response, but the key for us as communicators is to understand why it happens in the first place. Why you have a similar reaction when you pick up a 40-page report.

Experience has taught us to dread length. Long documents, long speeches, long meetings usually mean two things: boredom and confusion. We’ve been trained that lengthy documents and diatribes are synonymous with repetition, with irrelevant information, with clichés. We’ve come to learn that the thicker the tome the more likely we are to be faced with language we don’t understand—jargon, acronyms, fancified words—and don’t care about. We get left behind. We get confused. We yawn.

And we’ve learned this by the time we are nine.

So why would we continue to write long or speak at length?

Two reasons. First, we think we’re impressing the bejesus out of people when we go on at length. We think we’re showing readers and listeners how bright we are, how diligent we are, how hard we have worked. Writers believe that when people pick-up their 40-page report they will say, “Wow. Forty pages. This is impressive. This person should be promoted.”

In fact, what we actually say before we’ve even read the report is this: “Good grief. Who’s the idiot that thinks I’ve got time to read 40 pages.”

The second reason we write long and often speak at length is because we don’t edit what we’re saying. We’ve already touched on this, but many of us stop when we’ve finished the first draft of our document or our presentation. We breathe a sigh of relief. “Glad that’s done.”

But it isn’t. In fact, the work is only just starting—and it is work. Renowned humorist and author Mark Twain once said, “I didn’t have time to write a short letter, so I wrote a long one instead.”

Editing requires us to rethink, reorganize, and reword, but the results are well worth the effort. See for yourself in these examples from the Plain Language Action and Information Network (PLAIN), a working group of U.S. federal employees from different agencies and specialties who support the use of clear communication in government writing.

Try Your Hand

What would you do to make these paragraphs from the Plain Language Action and Information Network website less wordy?

1. If the State Secretary finds that an individual has received a payment to which the individual was not entitled, whether or not the payment was due to the individual’s fault or misrepresentation, the individual shall be liable to repay to State the total sum of the payment to which the individual was not entitled. (54 words)

2. When the process of freeing a vehicle that has been stuck results in ruts or holes, the operator will fill the rut or hole created by such activity before removing the vehicle from the immediate area. (36 words)

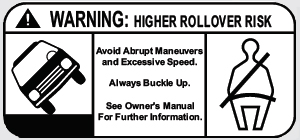

3. This is a multipurpose passenger vehicle which will handle and maneuver differently from an ordinary passenger car, in driving conditions which may occur on streets and highways and off road. As with other vehicles of this type, if you make sharp turns or abrupt maneuvers, the vehicle may roll over or may go out of control and crash. You should read driving guidelines and instructions in the Owner’s Manual, and WEAR YOUR SEAT BELTS AT ALL TIMES. (77 words)

Turn to page 30 to see what the government departments and agencies actually did.

Lots.

Avoid the tired and trite

We understand the elements that contribute to a lack of conciseness. Let’s start with the obvious, and maybe the easiest. Some of these have to do with the words and expressions we use. Many are simply longer than they need to be.

For example what is the difference between:

In order to versus To

Whether or not versus Whether

Compare these sentences:

In order to understand why kale is inferior to spinach, we need to start with the soil.

To understand why kale is inferior to spinach, we need to start with the soil.

It’s your decision whether or not you attend the meeting.

It’s your decision whether you attend the meeting.

There is no difference between the comparable sentences except length. If we use “to” instead of “in order to” we reduce the number of words from three to one, or 66 percent. The same is true of “whether” versus “whether or not.” It’s a small thing, but if we can effectively trim documents by a third it will enhance readability and improve clarity.

There are also expressions we tend to use almost by rote. We start conversations, meetings, e-mails with familiar phrases. It’s like taking the same route home every day from the office. Sometimes we pull into our driveway, not really aware how we got here. Communicating on autopilot is always risky.

These common phrases are often overused expressions or cliches. They really fall into two camps: those that have been around for decades if not centuries and those that are newer and have taken hold in the language. Here are a few examples:

As per our conversation

I look forward to hearing from you

Please note that

At the end of the day

Win–win situation

Think outside the box

Let’s touch base

Now these overused expressions are not likely to be misunderstood, but they are, quite simply, tired and trite. They lack impact. At the very least, they sound mundane and boring. At worst, they make us as communicators look unimaginative and half-hearted. They also add unnecessary words to our communication. Cut them out and we’ll cut down on length and zero in on relevant information. Count on it.

Take action

It’s also recommended—wisely—that we use the active voice. It not only requires fewer words, it’s more interesting, straightforward, and easily understood. Most sentences in the English language follow an active format: subject, verb, object. Yet, many reports, policies, research papers, formal presentations, and stud findings are written in the passive, not the active, voice.

Like this:

Popeye loves spinach. Subject. Verb. Object.

And like this in a more complex sentence:

Popeye believes spinach—not kale—is the perfect food. He thinks kale sucks. Popeye still leads the charge.

So let’s go passively into those good sentences.

Spinach is loved by Popeye. Object. Verb. Subject.

The perfect food is believed by Popeye to be spinach—not kale. It is thought by Popeye that kale sucks. Notice the “by” and “be.” These are indicators the passive voice is being used.

While we might agree with Popeye about kale, the passive voice construction is often awkward and always wordy. There are times when the passive voice is a good choice: when we want the focus on the object not the subject.

Maybe like this:

The divorce papers were signed by Brad and Angelina, who then embraced passionately.

Grammar books would tell us the important thing here is the divorce papers, not Brad and Angelina. Yeah, right.

How about this:

A great deal of meaning is conveyed by a few well-chosen words. [Passive] And a longing glance. [Not a sentence] Just ask Brad and Angelina. [Active]

Avoid repetition, repetition, repetition

As communicators we also have a tendency to repeat words, phrases, ideas, and examples. In some cases, this is done sparingly for emphasis or as a reminder of key points and messaging. Most of the time, however, it’s done because we haven’t taken the time to edit our writing or ourselves. Most repetition is, quite frankly, boring. It’s also unnecessary. If we’ve shared information with our audience once, why are we telling them again. If we’ve used the word “situation” once in a paragraph or statement, why are we using it two additional times. (Believe me, they got the message. “There is a situation.”)

Part of this issue relates to organization. If a presentation or piece of writing isn’t well organized, we may have to repeat content to ensure understanding. So making sure our thoughts and content are organized logically is important. Outlines, rereading, and reading a draft out loud will all help here.

The other reason we repeat information is we haven’t taken the time to edit what we’ve drafted in the first place. This is especially true if the talk or message is short. We think we’re fine because there aren’t too many words. However, editing is essential regardless of the nature of the communication, the complexity of the content, or the number of sentences/paragraphs/minutes.

In Short

Numerous other techniques can help us reduce length. Purdue University’s online writing lab recommends several tips starting with replacing vague words with more powerful and specific words. Like this:

Wordy: The politician talked about several of the merits of after-school programs in his speech. (14 words)

Concise: The politician touted after-school programs in his speech.

The Purdue OWL (online writing lab) also suggests checking every word to make sure it contributes something important and unique to a sentence. If words are dead weight, they can be deleted or replaced. As in this example from the OWL website:

Wordy: Eric Clapton and Steve Winwood formed a new band of musicians together in 1969, giving it the ironic name of Blind Faith because early speculation that was spreading everywhere about the band suggested that the new musical group would be good enough to rival the earlier bands that both men had been in, Cream and Traffic, which people had really liked and had been very popular. (66 words)

Concise: Eric Clapton and Steve Winwood formed a new band in 1969, ironically naming it Blind Faith, because speculation suggested that the group would rival the musicians’ previous popular bands, Cream and Traffic. (32 words)

In addition to wordsmithing, there is one other significant element to consider when looking to make sure what we say and what we write is concise: relevance. All too often we add details, describe things, and provide examples that are simply not necessary. They bore the audience (and may confuse them) and weigh our writing or presentation down.

I have a dear friend who overshares. The result is many of us tune out. I once asked her how her mother’s name was placed on a waiting list for a nursing home. My friend spent 10 minutes explaining about the local health authority’s home care program. I thought she had misunderstood and interjected that I was inquiring about the nursing home. My friend corrected me gently. First, she would tell me about the home care program, then nursing home care.

In her mind there was a logical connection between the two, and she had lived through both experiences. Unfortunately, I wasn’t interested in the home care information. My question was about nursing home care, and I hate to admit it, but I stopped listening with any intent early into the home care explanation.

Just because something is relevant to us or interesting to us doesn’t mean it will be to those we are communicating with. Indeed, remember the radio station our audience listens to avidly: WII-FM. What’s In It For Me? If our audience can’t find what they need in what we have to say and can’t easily see how our information is relevant to them, they will simply stop paying attention. And the purpose we had for communicating will not be achieved. We will have wasted our time and theirs.

Frankly, people are fed up with colleagues, supervisors, employees, suppliers, and everyone else in their workplace wasting their time with communication that doesn’t do the job it was intended to do. According to The State of Business Writing, 2016, 81 percent of people who write for work agree with the statement “Poorly written material wastes my time.”

Leaving the listener out of the conversation or the reader out of the material is a sure-fire way to get them to stop paying attention or to half pay attention. We want their whole attention. We need to look carefully at what we’re saying and ask:

• Does the audience need this information to understand what I’m saying or asking of them?

• Does the audience already know this information?

• Does this information provide context or background the audience requires?

• What is likely to happen if I don’t include this information?

• Is this information included because it is second nature to me as the subject matter expert?

Decipher This

Many U.S. states and the federal government have enacted plain language laws that require public-facing material to be easily understandable and usable. The paragraph below was the first to come under fire after New York enacted its legislation in 1977.

Original

The liability of the bank is expressly limited to the exercise of ordinary diligence and care to prevent the opening of the within-mentioned safe deposit box during the within-mentioned term, or any extension or renewal thereof, by any person other than the lessee or his duly authorized representative and failure to exercise such diligence or care shall not be inferable from any alleged loss, absence, or disappearance of any of its contents, nor shall the bank be liable for permitting a colessee or an attorney in fact of the lessee to have access to and remove the contents of said safe deposit box after the lessee’s death or disability and before the bank has written knowledge of such death or disability.

Can you figure out what this means? How would you make it concise? The former 121-word sentence was more than cut in half:

Our liability with respect to property deposited in the box is limited to ordinary care by our employees in the performance of their duties in preventing the opening of the box during the term of the lease by anyone other than you, persons authorized by you or persons authorized by the law.

Sixty-five percent of people surveyed for The State of Business Writing, 2016 said these are the top two problems with the writing they received:

• It’s too long

• It’s poorly organized

A Few Final Thoughts—Succinctly Put

It’s important for us as communicators to take a close, critical, and considerate look at what we say and how we say it. When it comes to conciseness, however, brevity may be imposed on us. Conferences, meetings, roundtables, panel discussions, and other oral presentation formats have for decades (if not longer) restricted speakers to a specific length of time. Often there was no enforcement of this requirement and the 40-minute presentation we were expecting drifts, usually painfully, into 65 minutes. More and more, speakers are given a five-minute warning, then a two-minute warning as the moderator or organizer moves to the podium or the next item on the agenda.

Today many forms, grant applications, entrance requirements, and more limit word length (as well as font and font size). For example, you may be asked to explain how your project will ensure more people get affordable access to spinach, and not the lesser cousin kale. Instead of being allowed to wax eloquently about the origin of Spinacia oleracea in Persia, you’re allotted 150 words at which point an online system will simply refuse to accept any more text.

Several years ago, a client of mine was complaining bitterly about his new boss (who was admittedly in the job he applied for and did not get). He wanted to demonstrate her silliness and rigidity. This was the example he used.

Staff had received an e-mail that said all material over two pages had to come with a one-page summary. My client had a 10-page report, and he wrote a summary that was one paragraph over the one-page limit.

His boss thanked him for the report and asked for a one-page summary.

My client e-mailed back to clarify, somewhat snarkily I presume, that his boss wanted him to take the one-page, one-paragraph summary and reduce it to one page.

His boss wrote back, seemingly nicely, to say, “That’s right.”

My client felt this was a prime example of how his new boss made absurd requests.

But was it? What happens if the boss accepted a summary longer than one page, albeit by very little. How long would the next summary be? And the one after that?

I applauded his new boss. Secretly.

People are digging in their heels when it comes to wordiness. It wastes time and does not add value to the communication. They’re busy, and they don’t have time for communications that ramble and meander. They also don’t want to have to work to understand a message or be drawn into content. And concise writing is more compelling.

Take a look.

This example is from an article by Laura Kelly on The Readable Blog, which according to a metric they use to measure readability is easily readable by only 25 percent of the general public.

There is currently a lively, ongoing controversy among many sociologists and other professionals who study human nature: theories are being spun and arguments are being conducted among them about what it means that so many young people—and older people, for that matter—who live in our society today are so very interested in stories about zombies. (58 words, 1 sentence)

How would you make it concise and much more interesting? Here’s what The Readable Blog did:

A lively societal debate rages among the human sciences. The contentious issue is: why are so many people fascinated by zombie fiction?

And just like that, no more deadly prose.

Try Your Hand—Revised

Original

1. If the State Secretary finds that an individual has received a payment to which the individual was not entitled, whether or not the payment was due to the individual’s fault or misrepresentation, the individual shall be liable to repay to State the total sum of the payment to which the individual was not entitled. (54 words)

Revised

If the State agency finds that you received a payment that you weren’t entitled to, you must pay the entire sum back. (22 words)

According to plainlanguage.gov, this example demonstrates conciseness techniques that more than halved the length of the original paragraph with no loss of meaning.

Original

2. When the process of freeing a vehicle that has been stuck results in ruts or holes, the operator will fill the rut or hole created by such activity before removing the vehicle from the immediate area. (36 words)

Revised

If you make a hole while freeing a stuck vehicle, you must fill the hole before you drive away. (19 words)

As PLAIN notes, using simple, straightforward language helps us say what we mean without extra word clutter.

Original

3. This is a multipurpose passenger vehicle which will handle and maneuver differently from an ordinary passenger car, in driving conditions which may occur on streets and highways and off road. As with other vehicles of this type, if you make sharp turns or abrupt maneuvers, the vehicle may roll over or may go out of control and crash. You should read driving guidelines and instructions in the Owner’s Manual, and WEAR YOUR SEAT BELTS AT ALL TIMES. (77 words)

Revised

A picture says in 19 words what originally took 77. And the message is clearer.