Game Theory

“Follow the Leaders” art installation popularly known as “Politicians Discussing Global Warming” by Isaac Cordal. Montreal, Canada, 2015.

Win‐win

We will not win alone. Much of this book has been about the building blocks of collaboration, such as transparency, kindness, logic, humility, adaptability, trust, and clear communication. Collaboration is a necessary ingredient of social change.

Accordingly, we should be sobered by the fact that human history is littered with failed collaboration and unnecessary conflict.

During the Cold War, the U.S. military hired mathematicians to parse the tragic logic of the nuclear standoff. Thinkers like John Von Neumann built the new discipline of game theory to precisely illuminate the terrible decisions facing political leaders. Game theory was used to explain market behavior and political conflict.

Over time, the discipline grew and evolved. Elinor Ostrom won a Nobel Prize in economics for showing how people can, in fact, work together to find creative solutions for common resources that they’d otherwise deplete if they only pursued their own selfish interests.1

Social change agents like us can similarly benefit from game theory to explain—and potentially avoid—shortsighted and selfish behavior that limits our individual and collective success.2

This chapter starts with three of the basic dilemmas of game theory. Then we’ll look at five ways to transcend these dilemmas. We’ll find lessons from nature, agriculture, and ice cream. Throughout, we’ll explore how these tools can help us chart a path to the social good the right way, the only way—together.

Three dilemmas

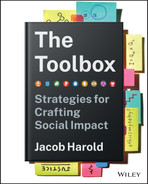

We’ll start with the most famous problem in game theory, the “prisoner’s dilemma.” Imagine two suspects held in separate cells. The prosecutor asks each to declare the other guilty. They can’t communicate with each other.

- If neither declares the other guilty (the two prisoners “cooperate”), each faces a light sentence—30 days.

- If both say the other one is guilty (the two prisoners “defect”), each faces a serious sentence—3 years.

- If one defects and the other does not, the defector is rewarded with freedom. The other gets the heaviest sentence—10 years.

When we consider the two prisoners as a pair, their best choice is clear: each should keep quiet and take the light sentence. But individuals acting in isolation feel the incentive to defect. No matter what the first prisoner believes the second will do, they may perceive that they will get a better deal through declaring the other guilty. That clouded perception favors an outcome that is actually against their best interest.

While the prisoner’s dilemma is the most famous of the models of game theory, it is not the only one. There are two other models worth noting here—“chicken” and the “stag hunt”—which offer further insight into the snares that prevent collaboration. Below I’ve laid out all three models as an interaction between two players, Antonio and Beatriz.

“All I have to do is divine from what I know of you: are you the sort of man who would put the poison into his own goblet or his enemy’s?”

Vizzini, The Princess Bride

The next model is the game of chicken. Chicken is like an abstract version of The Fast and the Furious action film franchise. Imagine two drivers barreling directly towards each other. The first to swerve is scorned as a cowardly “chicken,” and the other hailed as having nerves of steel. Of course, bravery has its drawbacks; if neither driver swerves, they’re both dead. Chicken is, of course, an absurd game. But, as we’ll soon see, it captures very real human behavior.

A third model is the stag hunt. The stag hunt is a game of probabilities. Two hunters are out in the same woods with an opportunity to collaborate. Each can choose to hunt either a stag or a hare. Hares are easier to snare, but they are small game. Stags are more difficult; they require the attention of both hunters. Even working together, the hunters have no guarantee of success; the probabilities are simply higher. Any two collaborators—people or organizations—will face a version of the stag hunt. How will each divide their precious attention? Both Jean‐Jacques Rousseau and David Hume used the stag hunt to describe the dynamics of the social contract.

Collective tragedy from individual dilemmas

Life, of course, is not a game. But all‐tooreal tragedy emerges from the dynamics captured in these models.

Why has humanity filled the sky with greenhouse gases? Because climate change is a global prisoner’s dilemma. Nations, companies, and individuals don’t trust that others will act for the collective good. So they—we—defect from a common purpose. And we all bear the sentence handed down by the sky. This is the “tragedy of the commons”—a collective manifestation of the prisoner’s dilemma.

Much of the history of human warfare is a history of leaders playing chicken with nations. This game reached a kind of rational absurdity in the Cold War with the concept of mutual assured destruction—aptly known by its acronym, “MAD.” Retaliatory murders among warring drug cartels have a tragic rationality when viewed in isolation. All too often, societal violence is a collective consequence of the game of chicken, where pride eclipses self‐interest.

Societies fragment into lonely and undernourished souls because so many people choose to focus on the hare, not the stag. It is not an epic betrayal that leads to jail time, like the prisoner’s dilemma. Instead, it is the lost opportunity for deeper engagement. It is the microwaved dinner at home when you could pool skills and resources to make a meaningful meal with your family, friends, or neighbors. Individuals lack the necessary faith—perhaps the rationality—to invest with others in something bigger. Instead of choosing community, they choose isolation.

These tragic outcomes can be demonstrated mathematically and seem inevitable when looked at through cold, rational calculus. And yet the world is in fact full of collaboration. Every partnership is evidence of the ability of humans to work together, every exchange is evidence of the possibility of trust, and every compromise is proof that we are not, in fact, chickens.

It turns out that game theory models provide us with clues for how to escape their traps. But before we explore them, let’s discuss what happens when we—knowingly or not—settle into a pattern.

Equilibrium

So much of social change is about trying to break out of a situation that seems stuck. It is worth pausing to ask: how do situations settle? What really is an equilibrium?

Let’s look at a simple but revealing example. Imagine a long beach with people happily spread across it, soaking in the sun and ocean breeze. There are two ice cream vendors on the beach. Each is proud of their ice cream and wants to serve it to as many people as possible.Where do they set up? One at either end or both in the middle? Something else?

It turns out that—assuming they’re trying to maximize their share of the territory—both will end up in the middle. If they start on opposite ends, either could move towards the middle and, therefore, take over more than half of the “territory.” (This territory is nothing formal, simply the area from which it is fastest to walk to a given ice cream stand.)

This is an equilibrium. Once the vendors have both set up shop in middle of the beach, they’ll stay there. And hopefully they’ll become friends and maybe even trade hints so they each become more successful. But we also can’t deny this arrangement is worse for the beachgoers at the far ends of the beach.

The mathematician John Nash, famously portrayed in the film A Beautiful Mind, formalized a way to think about this type of situation, later called the “Nash equilibrium.” When a group of players interacts over time, they are prone to settle into specific behaviors. These behaviors reach an equilibrium when no individual wants to unilaterally change, given their knowledge of how everyone else behaves. That equilibrium may or may not be optimal for the group as a whole.

These balanced equilibriums, optimal or not, are by nature “sticky” but not permanent. What if a third vendor arrives on our ice‐cream–laden beach? All game‐theoretical hell breaks loose. The third vendor can join the first two in a cluster in the center—but then anyone could nudge just a bit to either side and capture half the market. They could spread out, but they’d face constant incentive to move. There is no equilibrium. The situation is unsettled and ripe for something new.

This is a trivial example of ice cream vendors. But in the real world—especially in unsettled times—there is an opportunity to break loose and find something better.

In the Age of Flux chapter, we considered the notion of a “plastic hour,” the realization that today’s complex, rapidly changing world may offer an opportunity for agents of change. The equilibriums of the moment seem ripe for transformation.

Transcending the dilemmas

Each of the models above is what we might call a “toy model”—an intentional oversimplification. It does not capture every nuance of a real situation. It isn’t meant to. Instead, these models focus our attention on the most important aspects of each actor’s choice.

So while we can’t confuse the models with reality, we can recognize the power of play. Thinking through games allows us to experiment, to explore, and to find joy in the search for better outcomes.

Scholars and practitioners have spent countless years looking for opportunity in these games. Below, we look at five lessons that games have taught us about how to achieve better outcomes together. In each case, it turns out that the solution to successful collaboration can be found by understanding the limitations of the model itself:

- Information: Information can help to remedy the pathologies of these dilemmas.

- Repetition: Our interactions usually are not isolated instances but links in a chain; over time we can build trust.

- Institutions: We can build structures to help facilitate shared purpose.

- Virtue: Kindness and generosity can transcend the temptation to defect.

- Abundance: Seeing sacrifice and gain through an abundance mindset brings more options to the table.

Information

Sometimes, lack of access to information is a feature of a situation. It’s true that prosecutors will offer one suspect a deal without the other suspect knowing of it. But when facing decisions, we usually have access to more information than the characters in these simplified games: we share a lawyer with the other prisoner, we know the proclivities of the other driver, or we had breakfast with the other hunter.

The good news is that changemakers are rarely working in isolation. We are not making decisions in complete ignorance of others. In the modern world, we have immense access to information. A web search can help us get the information we need. We also have access to each other; we can have a conversation.

Sometimes getting the right information requires structural changes. Making information visible, and therefore valuable, requires transparency—the willingness (or legal requirement) to openly share details about your work with the rest of society. Public capital markets rely on information. That is why Michael Bloomberg is a billionaire; he created a media empire by carefully tailoring financial information for his customers’ needs.

The open flow of information makes a market more fair. Insider trading is illegal because it relies on insider information and thus betrays the supposed logic of the overall market. Even free samples at a farmers’ market provide transparency; customers get an idea of the quality of the food they’re buying.

Information flow enables collaboration and alignment among social change organizations. The United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are an attempt to align our global efforts and track our collective progress.3 The SDGs have become a common anchor across corporate, government, and philanthropic efforts, highlighting shared purpose and enabling shared measurement.

Transparency is a key weapon in the battle against corruption. Too often, public funding meant to provide relief to society is siphoned off by those corrupt few who control the money. Research shows that publishing data—especially about financial flows—curtails corruption. Data might be shared online, in the media, or even on a big poster in the middle of the village square.

Such strategies do not prevent small‐time graft or every misdirection of funds. But transparent financial information creates a basic shared understanding of where the resources are and limits the ability of nefarious actors to take advantage of their community. And it gives the effective power of accountability to people who crave it.4

My own work has been built upon my deep conviction that transparency of information holds transformative power in the work of social good. GuideStar’s founding purpose was to provide information to donors to help them make good decisions. I joined the organization out of the belief that, collectively, civil society would be stronger if information flowed easily throughout the nonprofit sector. Not only would donors make better decisions, but nonprofits could better learn from each other, and the rest of society could better understand the purpose, value, and operations of nonprofit organizations.

A colleague organization, Foundation Center was started in 1956 in response to (false) accusations that foundations were funding communist infiltration . The solution was radical transparency: opening a library in New York City where foundations freely shared information about the grants they were making. Over time, nonprofits began using that information to find out who might give them funding and who else was working on the same issues. And funders could use the information to discover others who shared their passion.

These two organizations were opposite sides of the same coin. So we got married. The merger of GuideStar and Foundation Center in 2019 to form Candid was a double victory against the prisoner’s dilemma. First, the two parent organizations had to overcome their own narrow interests to execute the merger itself. Second, the combined entity was better positioned to help donors and nonprofits collaborate. The information infrastructure was finally aligned with common purpose.

“Interdependence is iterative.”

adrienne maree brown

Repetition

In the simple versions of the prisoner’s dilemma, stag hunt, and chicken models there is a single interaction. The reality is that human society is built upon repeated interactions. Over and over, we find ourselves confronted with the same people. Our reputation with those individuals matters.

The best way to gain trust is to show trust. Those who put their trust in others typically earn it back many times. Conversely, just as a reputation for trustworthiness and for trusting is valuable, a reputation for being a sucker is not.

Accordingly, repeated games require balancing the power of trust with the need for accountability. As a changemaker, you must be willing to stand up for yourself.

The simplification of these games lends itself to computer modeling and rigorous experiment. Over the decades, researchers have explored countless strategies in repeated prisoner’s dilemma games.5 And, after billions of experimental iterations, the evidence is clear: there’s one strategy that works best. That strategy is known as “tit‐for‐tat.”

One can think of “tit‐for‐tat” as a strategy of (1) generosity, (2) accountability, and (3) forgiveness. You begin by cooperating (generosity) and stay there as long as your partner does the same. If you are betrayed—as we all are likely to be at some point—you switch to a “defect” strategy (accountability). Once—if—your partner cooperates again, you return to cooperation (forgiveness).6

In real life, we will not find ourselves in such a consistent, one‐dimensional situation. But the underlying lesson is clear: kindness can be a good strategy—when it is tempered with accountability and clarity.

Institutions

The economist Elinor Ostrom has analyzed scale examples from around the world where people have collaborated to share limited resources and protect their future livelihoods. The secret of collective action, Ostrom says, is the time‐consuming work of “getting institutions right.” If all institutions are games with sequences of available options, information, rewards, and punishments, then successful institutions make people want to play. They clearly define who can play and give them a voice in shaping the rules together. Players pool knowledge, trust each other to keep their word, and monitor themselves to make sure they do.

Ostrom’s book, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action, provides a number of examples of these concepts at work. Below are two that both involve mobilizing labor and resources for irrigation. The first one, in the Philippines, is a federation that formally incorporated in 1978 with antecedents dating to the 19th century. The second, in Sri Lanka, is a new institution that grew up to resolve long‐standing water disputes in the territory.

“By bein’ kind to strangers you run the risk of them bein’ kind to you.”

Jeff Daniels

Virtue

Kindness, cooperation, sacrifice, and vision are more than just pretty words on a cross‐stitch embroidery sampler. They are genuine solutions for changemakers who want to avoid or escape the trap of unproductive games.

When I was in business school, my professor shared the challenges of the prisoner’s dilemma and asked the class to do a series of experiments to try it out ourselves. I distinctly recall his bemused frustration that we were not nearly so greedy as he expected business students to be. Or more precisely, we were not rational in the way he had assumed.

For most of us, our inclination was to cooperate. Our decision made sense in the broader theoretical framework of game theory. Students like me were in the middle of a repeated game; this was not the last time we would be interacting with a given classmate. It was in our rational interests to collaborate, not to betray or defect. And, well, some people are just nice.

I do not want to deny the brutality of life and the fact that sometimes harsh calculus is necessary. There is evil in the world; though perhaps more relevantly, there is fear that leads to selfishness on the part of those with whom we interact. We’d be fools to ignore that.

Game theory gives us permission to default to virtue. The “tit‐for‐tat” strategy is a kind of summary of virtue: start with kindness, show discipline when presented with bad behavior, and offer forgiveness when others show their best selves.

Abundance

If I eat the last slice of mushroom pizza, you’ll get none. If investors demand 75% of the equity in a new startup, there’s only 25% left for the founders.

Cases like these are “zero‐sum games.” There is a single pool of spoils; benefit for one is loss for another.

But here’s the good news: life tends to be multidimensional. I might actually want more salad and be happy to give you the last slice of pizza. The founders of a social enterprise might gladly yield ownership control if they can better achieve their mission by meeting the investors’ equity demand. With a broader view, we turn a “zero‐sum” situation into a generative “non‐zero sum” moment.

The abundance mindset shows up in negotiations. One useful tool to keep in mind is your “BATNA”—”best alternative to negotiated agreement.” Knowing your BATNA helps you if there is no agreement. That baseline can create a sense of confidence going into a negotiation.

When I led GuideStar in the merger negotiations that would eventually create Candid, I knew that we had a strong BATNA: no matter what happened, we could maintain our work with the confidence that we were creating sustainable impact. That baseline of confidence allowed space for creativity to find something even better for our people and our work.

There are times when one person’s gain is in fact another’s loss. As we discuss in the Ethics chapter, it’s the right moral and strategic choice to be honest about those consequences. And, as discussed in the Behavioral Economics chapter, there are even cases where human irrationality leads to a “negative‐sum game” where people sacrifice solely so that others suffer.

But as social change agents, we have an opportunity to expand the aperture of possibility beyond the zero‐sum and negative‐sum mindsets. At best, we can imagine and articulate broader options as we work with others to solve shared problems. Our interactions themselves can yield abundance.

“There are at least two kinds of games. One could be called finite; the other infinite. A finite game is played for the purpose of winning, an infinite game for the purpose of continuing the play.”

“Infinite play resounds throughout with a kind of laughter. It is not laughter at others who have come to an unexpected end…it is laughter with others with whom we have discovered that the end we thought we were coming to has unexpectedly opened.”

James P. Carse7

Game theory and social change organizations

You don’t have to look far to see how we in the world of social change can get caught in the snares described by game theory. Social change organizations might dream of the benefits of cooperation, but they are usually oriented towards their own familiar funding streams, staffing models, programmatic strategies, and organizational cultures. It can be easy to let an existing equilibrium prevail over the prospect of a partnership.

Let’s consider a hypothetical example. Imagine two complementary human services nonprofits. One offers mental health programs in local high schools, and the other provides services to homeless youth. Each receives $100,000 a year from the same local community foundation. Both nonprofits know the foundation seeks opportunity for greater impact through collaboration; in fact, it will provide $300,000 in total funding for a well‐designed collaborative effort to provide wrap‐around services.

The community foundation has presented a possibility in such a way that the best interests seem clear. But both nonprofits are nervous. If the collaboration does not work out, will the community foundation cut their core funding? Might one organization betray the other and tell the community foundation it could provide both types of services on its own for just $250,000?

To that worry and distrust, add uncertainty and short‐term costs: Even if, for example, the executive directors of the two organizations want to collaborate, staff members may resist. They might say the partnership will force them to restructure the program, redo internal systems, abandon their unique culture, or—horrors!—admit the weakness of their organization.

These two nonprofits are missing a prime opportunity to better serve the young people they care about. Both nonprofit leaders, by understanding that they are in the grip of the dilemma, can transcend their natural reluctance and pursue their true best interests.

“New conditions, like our interdependent, globalized world, require new ideas.

Dividing people into ‘us’ and ‘them’ is out of date.”

Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama12

Enabling collaboration through communication

Collaboration can challenge social change leaders’ sense of identity. We would be wise to respect how emotionally and intellectually difficult it can be for social change practitioners to acknowledge that they cannot succeed alone. So how might we transcend those barriers? Below, I’ll suggest eight strategies to help enable collaboration. The first four are techniques of communication.

Define the community.

Collaborations are more likely within the boundaries of a shared identity. Sometimes that identity has to first be articulated. The first step is to identify what the groups have in common: “We are defenders of tropical rainforests” or “We serve people without housing in Miami.” Overwhelming evidence suggests that a sense of community plays a central role in human decisions.13 Collaboration requires a sense of commonality, and when that commonality is described, it becomes actionable.

Celebrate each other.

The short‐term incentives for organizations are to take credit for wins and to seek as many resources as possible. But the long‐term interests of common purpose require others winning, too. This dynamic becomes most acute around fundraising (whether for donations or investments), where there is often a perception that it is a zero‐sum game. Some organizations transcend this, though. Movement Commons has built cohorts of nonprofit fundraisers that explicitly and systematically ask their donors to also donate to partner organizations. By doing so, they are creating an opportunity for funders to broaden their impact on an issue they care about.

Name your weakness.

Introductions at Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meetings often begin with, “My name is X, and I am an alcoholic.” This statement shows trust and humility on the part of the speaker. Similarly, social change organizations can open themselves to collaboration by acknowledging their limitations as independent actors. Naming the problem need not create a pessimistic atmosphere; indeed, the next phrase at an AA meeting is often something along the lines of, “… and I’ve been sober for five years.” And its power extends to the listener, making them more likely to admit their own weaknesses. Then, explore opportunity upon a foundation of honesty and humility.

Show successful examples.

One powerful human tendency, as we discuss in the Behavioral Economics chapter, is to do what we see others doing. Organizations are far more likely to collaborate if they see relatable examples of other successful collaborations. This process can create a virtuous circle of sharing simple examples, building confidence, bringing in new data, and making larger steps possible.

Make explicit the implicit division of labor.

Over time, organizations tend to differentiate themselves. Consider nonprofit service providers in a medium‐sized city. One organization takes the west side of a town, another the east; or one handles middle‐school students, another highschool students. Once potential collaborators acknowledge those differences, they can capitalize on them. But for that differentiation to translate to collaboration, someone needs to say explicitly what implicit division of labor may have developed over time. Without that openness, participants may hesitate to speak clearly or act decisively, afraid to offend or stereotype. When the division of labor is discussed openly, conflicts or differing perceptions can be addressed directly.

For example, in 2003 I was tasked at Rainforest Action Network (RAN) with leading a campaign to pressure Ford Motor Company to accelerate the transition to clean vehicles.

The Sierra Club was involved in similar campaign and was seen by Ford as more moderate. The executives at Ford would talk to the Sierra Club but ignore us. As best we could tell, Ford saw us as too radical to even talk to. Then, a new organization called Bluewater Network came into the campaign and engaged in even more aggressive tactics, posting a full‐page ad in the New York Times with a picture of Bill Ford with Pinocchio’s nose. Ford’s attention immediately swung to us. We were able to engage with them because Bluewater had opened space that allowed us to no longer seem quite so radical.

Enabling collaboration through structure

Organizational ecosystems have a structure. There could be one large organization or many small ones; they might all be for‐profit businesses, all nonprofits, all government agencies, or a mixture. In a collaboration, some subset of those organizations works together for common purpose. The arrangement of that collaboration is critical.

Here, I offer some suggestions on how to optimize impact through structure.

Identify the guide.

Multilateral collaboration greatly benefits from a guide—a person or organization—to manage the process, provide encouragement, and help solidify a shared vision.15 Without this structure, the short‐term incentives of the individual participants will tend to prevail, and the collaboration will dissolve. Pure top‐down management will not work; if nonprofit participants feel a foundation is forcing them to engage, the partnership will not be authentic. Ideally, participants can identify a facilitator who is aligned with the shared purpose but is seen as neutral relative to the specific interests of individual participants. Like a guide leading a group of climbers up a mountain, this facilitator is both a participant and a leader. They bear costs and reap shared rewards.

Reassess the formal structure.

Collaboration does not necessarily require formal restructuring. You do not need to merge with your partners, have a formal legal contract, acquire your vendors, or even set up a formal network. But any of those alternatives might, under the right circumstances, be the right choice. In the Institutions chapter, we will examine broader questions of institutional structure. But at the very least, consideration of collaboration is also a moment to consider structural change.

Design collective systems.

Formalized systems for knowledge sharing, governance, and external communications not only create value; they also reinforce collective identity and incentivize organizations to remain in the group. This design makes it more likely that the collaboration will last long enough to achieve the desired change.

Be intentional about transparency or discretion.

In general, collaboration is most effective when it is forthright and transparent. That builds trust on the part of those outside of the actual negotiations. With that said, in politically fraught contexts, there can be exceptions. We may not want to work together in smoke‐filled rooms, but sometimes collaboration behind the scenes can yield the best results. Secrecy can be appropriate at times—but should be an exception, not the rule.

Game theory highlights some of the consequences of human weakness. But it also offers us a pathway towards collaboration. Ultimately, the recipe is simply: generosity, accountability, and forgiveness.

Game Theory Takeaways

- Figuring out how to align our work with others is so complex and important that it deserves its own science. That science is game theory. The consequences of our actions are partly determined by other people’s simultaneous decisions.

- The “prisoner’s dilemma,” the most famous game theory thought experiment, demonstrates how people choose betrayal even though mutual trust is in their best shared interest. A decision that seems narrowly rational is often the product of greed or fear.

- Even when changemakers dream about cooperation, we can act against our best interests. Our own cozily familiar funding streams, staffing models, programmatic strategies, and organizational cultures often favor stability over the prospect of partnership. Game theory teaches us how to overcome those traps.

- The natural world has a simple but powerful lesson for changemakers: life is more than a game of the survival of the fittest. Mutual support is a successful strategy for adaptation and change in a complex and fast‐changing world.

- With just one pool of spoils, one person’s gain is another’s loss. But life is more complex: in almost every situation, there are many dimensions to consider. Social change agents can develop an abundance mindset that imagines broader options to solve shared problems.

- We find ourselves continually confronted with the same people. Generosity is a good strategy for these repeated interactions. The highly successful “tit‐for‐tat” strategy begins from a stance of generosity and stays there as long as one’s partner cooperates. But as soon as you are betrayed, you respond in kind and then wait until your partner cooperates again. Then, in perpetuity if possible, you continue to be generous.

- Information flow is another way to avoid the traps of game theory dilemmas. Changemakers like us rarely work in isolation. We have access to information and to each other. Information isn’t always enough; mechanisms to make information both useful and visible create accountability and structure for conversation.

- The secret of collective action, according to Elinor Ostrom, is the time‐consuming work of “getting institutions right.” If all institutions are games with sequences of available options, information, rewards, and punishments, then successful institutions make people want to play. Well‐structured collaborations maximize impact and are more likely to last long enough to achieve the desired change.

- The right attitude opens space for collaboration. It is emotionally and intellectually difficult for social change practitioners to acknowledge that they cannot succeed alone. Among the techniques to surmount these sentiments: describing your common ground, speaking honestly about your weaknesses, and sharing successful examples of similar collaborations.

- Kindness, cooperation, sacrifice, and vision are genuine solutions for changemakers who want to avoid the traps of unproductive games. Game theory shows that in long‐term relationships, cooperation is, quite simply, a good strategy.

Notes

- 1 Ostrom (1990).

- 2 This chapter draws from an article I wrote for the Stanford Social Innovation Review, “The Collaboration Game: Solving the Puzzle of Nonprofit Collaboration.” April 26, 2017.

- 3 For the goals themselves, see: https://sdgs.un.org/goals. For a tool to map any organization’s work, including your own, to the SDGs, see https://sdgfunders.org/wizard/.

- 4 Chen, Can, and Sukumar Ganapati. “Do transparency mechanisms reduce government corruption? A meta‐analysis.” International Review of Administration Sciences, August 31, 2021. Available on Sage Journals: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/00208523211033236

- 5 Axelrod, Robert; Hamilton, William D. (27 March 1981), “The Evolution of Cooperation,” Science, 211 (4489): 1390–96.

- 6 I’ll add that another successful strategy is a modified version of tit‐for‐tat where you show random preemptive forgiveness. We could call it a “grace strategy.”

- 7 Carse (1986). The first quote is from pg. 3; second from pg. 25.

- 8 Sheldrake (2020), pg. 88.

- 9 Sheldrake (2020), pg. 17.

- 10 See Suzanne Simard’s Finding the Mother Tree (Knopf 2021) and Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees (Greystone 2016).

- 11 Thomas (1978), pg. 10.

- 12 Lecture, “Working Together for a Peaceful World,“ organized by Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam International Foundation. October 15, 2020. The Dalai Lama was speaking from the Thekchen Chöling complex in Dharamsala, Himachal Pradesh, India.

- 13 Turner, John C. “The significance of the social identity concept for social psychology with reference to individualism, interactionism and social influence.” British Journal of Social Psychology, September 1986, 237–252.

- 14 Wei‐Skillern, Jane, and Norah Silver. “Four Network Principles for Collaboration Success.” The Foundation Review, Volume 5, Issue 1, 2013.: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1009&context=tfr

- 15 Kania, John and Mark Kramer. “Collective Impact.” Stanford Social Innovation Review. Winter 2011.