An Age of Flux

In 2012, the Atlantic Ocean swallowed the roller coaster at Casino Pier in Seaside Heights, NJ.

Photo by Julie Dermansky

“The real problem of humanity is the following: we have paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and god‐like technology.”

E. O. Wilson1

“We are relying on nineteenth century institutions using twentieth century tools to address twenty‐first century problems.”

Ann Mei Chang2

Life in a plastic hour

In 1862, a Dutch ophthalmologist accidentally burdened the year 2020 with significance. Herman Snellen’s scale set “20/20” as “normal” sight. Over time, those four digits leaked into other realms of life. “2020” came to evoke a sense of visual—even strategic or moral—clarity. Countless executives sought to capitalize on that association by writing strategy documents with names like “Vision 2020.” (I was as guilty as any.)

In retrospect, 2020 now feels like a pivot moment away from clarity. The COVID‐19 pandemic shook an already unstable world. Slowly building crises of climate, democracy, and inequality all seemed to explode at once.

Later in this chapter I will argue that we are in a “plastic hour” (perhaps even a plastic century), a time when change is more possible. But to change the world, you must first see it as it is. So, let us set our toolbox down on the ground of reality. Below is a whirlwind tour of our early‐21st‐century moment, through the good, the bad, and the fast.

Say it plain: that many have died for this day Sing the names of the dead who brought us here.

Elizabeth Alexander

The Good

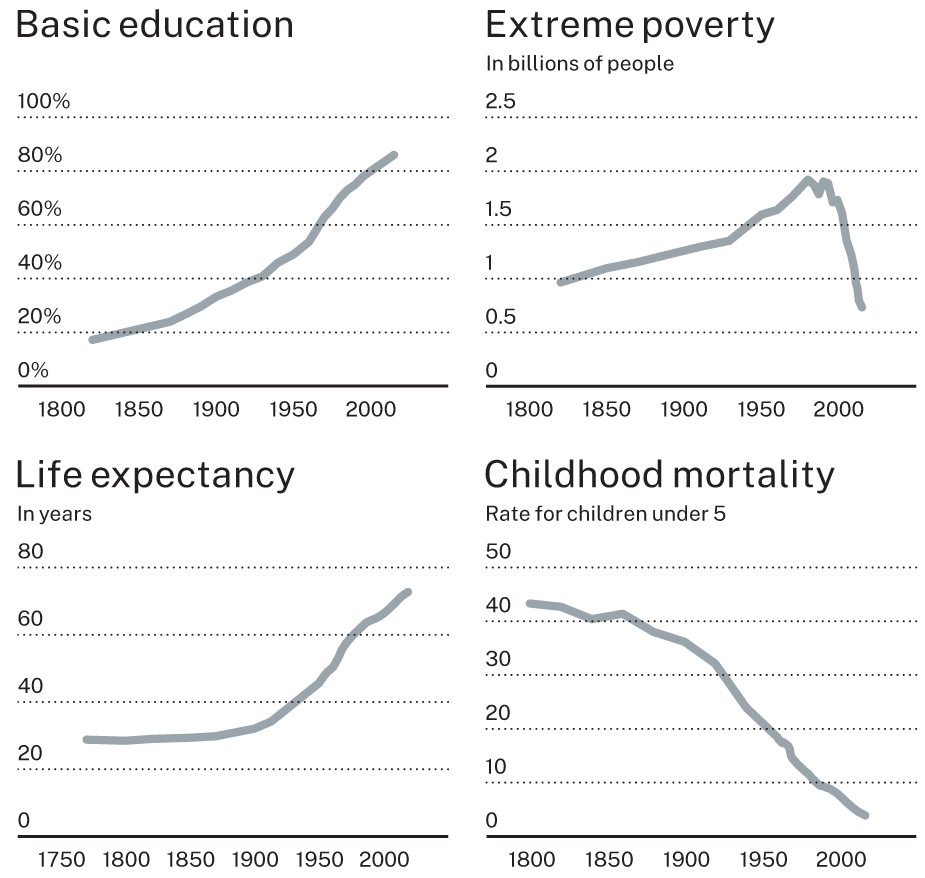

Billions have escaped extreme poverty. Infant mortality has plummeted, and lifespans and literacy have risen. Deaths from violence—still too high—have dropped since the bloodbaths of past eras. And, inconsistently, in bursts and with setbacks, the full range of humanity is getting a chance to love whom they would love, to be who they are, and to recognize the immense diversity of the human experience. We, in fact, have much to celebrate.3

Source: OurWorldinData.org

These are but some of the things we overcome But let us come to be more than their sum.

Amanda Gorman4

The Bad

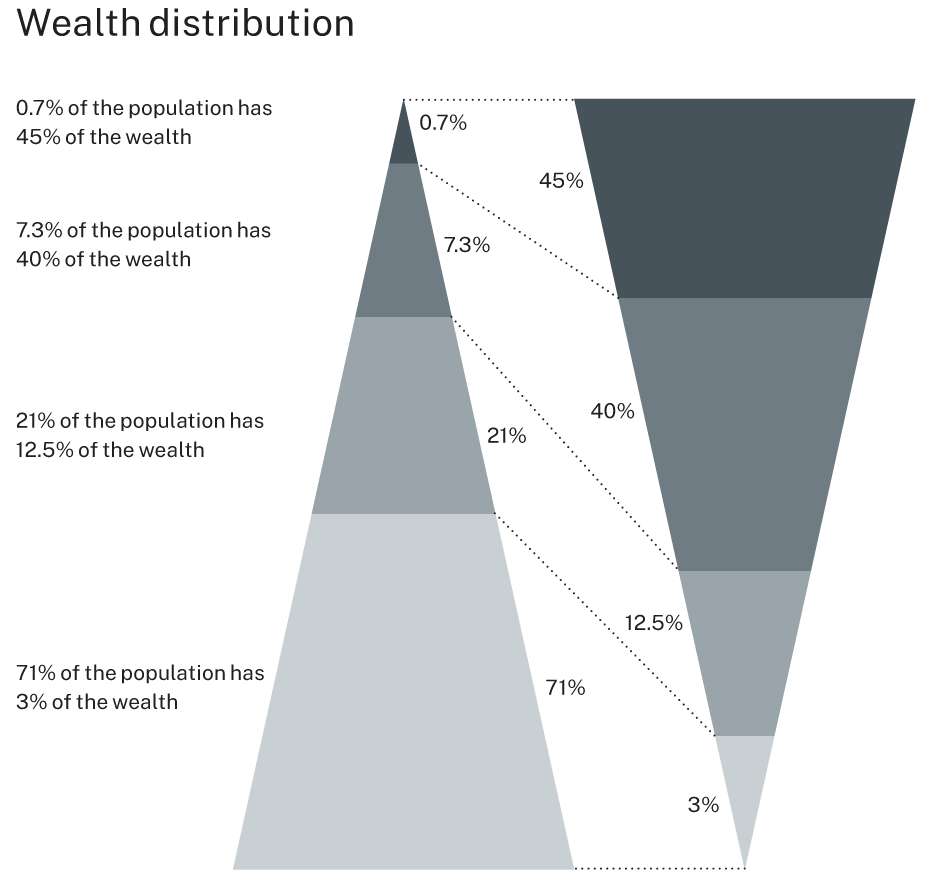

And yet, we must confront the reality of raw injustice faced by billions and a struggling planet. 400 million people lack access to essential health services.5 2.4 billion people do not have access to toilets.6 860 million people are undernourished.7 10 million tons of plastic are dumped into oceans annually.8 3 million tons of toxic chemicals are released into the environment each year.9 2 million people—disproportionately Black and Brown—are incarcerated in the United States.10 The list of injustice goes on and on and on.

As change agents, we face a paradox. The world has seen real progress. If we deny that progress, we insult those who fought for it. But if we ignore the challenges of the world, we betray ourselves and future generations.

Source: Visualization by Femke Nijsse based on data from PAGES2k consortium published in “Consistent multidecadal variability in global temperature reconstructions and simulations over the Common Era,” Nature Geosciences, volume 12, pages 643–649 (2019)

Source: Credit Suisse Global Wealth Databook

“Change is the one unavoidable, irresistible, ongoing reality of the universe.”

Octavia Butler11

The Fast

The metronome of history clicks faster. We find ourselves in the middle of what has been called “the great acceleration,” where we witness a change in the very pace of change. That is, we face not only the velocity (speed) of ideas and events but also the acceleration (increase in speed). Information pours into our minds; culture is a blur; politics moves to a next phase before we understand the previous one.

Pope Francis called this phenomenon “rapidification” and highlighted that it is not just an external phenomenon but a psychological one. He saw humanity as being caught in a temporal vice: “Although change is part of the working of complex systems, the speed with which human activity has developed contrasts with the naturally slow pace of biological evolution.”12 We are outpaced by the change we have wrought.

Source: OurWorldinData.org

But, I think, the future is also another thing: a verb tense in motion, in action, in combat, a searching movement toward life, keel of the ship that strikes the water and struggles to open between the waves the exact breach the rudder commands.

Ángel González

This acceleration has immediate implications for decision makers of all kinds. In 2017, Gen. Joe Dunford, then chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, considered the effect on military affairs. He explained, “Decision space has collapsed” and the acceleration of time “makes the global security environment even more unpredictable, dangerous and unforgiving…Today, the ability to recover from early missteps is greatly reduced.”13 The compressed space for reaction is particularly acute in war, but just as relevant for social change.

There are many causes for the collapse of decision space. One core driver is “Moore’s Law,” Intel founder Gordon Moore’s observation that the power and cost‐efficiency of microchips tends to double every 18–24 months. We have all witnessed the extraordinary acceleration of computing power that has followed. It is so fast that it is most appropriate to show the graph logarithmically (that is, 10, 100, 1000, etc.).

Innovation theorist Bhaskar Chakravorti has countered that societal change happens only half that fast—what he has jokingly called “demi‐Moore’s law.”14 Technical innovation does not happen in a social vacuum. In an interconnected world populated by intertwined organizations, change requires the social and political wherewithal to align disparate efforts across multiple actors and organizations. This complexity is the brake pedal that balances the force of the accelerator.

Source: OurWorldinData.org

Taken together, these two laws—Moore’s Law and demi‐Moore’s Law—illustrate our predicament: constant, accelerating innovation constrained by increasing interconnection and complexity. Let’s briefly examine four dimensions of this predicament: technology, culture, ecology, and politics.

“…as if time were not a river but an earthquake happening nearby.”

Roberto Bolaño15

Technology: The Fourth Industrial Revolution

We are entering the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The first three technological earthquakes could each be summed up in a single word: steam, electricity, and computing. Each changed the structure of society. The upheavals of the Third Industrial Revolution—mobile, cloud computing, social media—are by no means over; they will echo for decades to come.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution has a different character. It cannot be distilled into a single technology; instead, it is a cluster of technologies emerging on the frontiers of change. I’ll suggest the shorthand QARBIN (pronounced “carbon”) to capture the key technologies that make up the Fourth Industrial Revolution: quantum computing, artificial intelligence, alternative energy, robotics, biotechnology, blockchain, new interfaces, the Internet of things, and nanotechnology.

“Only the historian of the future will be able to assess the net effect of the machine age on human character and on man’s joy in being and his will to live.”

Helen and Scott Nearing16

Each technology could revolutionize our world. We cannot know which will be the most transformative. What we can know: this cluster of technologies is likely to cause dislocations equal to those of the first three industrial revolutions. The dreams—and nightmares—of science fiction are coming true: customized children, universal surveillance, fully autonomous warfare, self‐replicating intelligence, and the metaverse.

Culture: The humanity of change

Technology has fundamentally restructured human communications, bringing promise and peril to our work as changemakers.

For millions of years, communication was limited by the speed of human legs or the volume of the human voice. The printing press and postal services enabled ideas to move faster. The telegraph and the telephone connected vast distances in real time. Radio and television wove together a fabric of human stories. Through all of this, humanity has had to adjust, to evolve, and to react to the implications of these technologies.

In the second half of the 20th century, for better or worse, it seemed we might be heading to one global monoculture, where every corner would have a Starbucks and every teenager would listen to the same music. Many shared a sense that technology was driving cultural convergence.

“‘Future shock’ is the shattering stress and disorientation that we induce in individuals by subjecting them to too much change in too short a time.”

Alvin Toffler17

The early part of the 21st century, however, has shattered a once‐emerging monoculture into seven billion pieces. The Internet—and, in particular, social media—has thrown that once‐confident understanding of the near future into question. The friction once inherent in communication seems to have played a crucial role in cultivating a type of cultural stability; conspiracy theories previously had to pass through intermediaries or at least find deep adherents before they could spread. Now, with a few quick “reshares,” a once‐unthinkable idea can permeate the discourse.

The past two decades would suggest that on some deep cognitive level we humans are ill‐suited for the social media age: our attention is fragmented, our body images are distorted, and our sense of community—even reality—is filtered through screens.18

These challenges do not just test civic culture and human decency. There are deep practical implications for the work of social good. It is hard to solve problems with others without shared truth or shared trust.

For those trying to make a better world, we can take solace that our recent fragmentation reflects the diversity of the human experience. We can celebrate that we did not end up in a global monoculture. But we should also acknowledge that, in some ways, change has become harder as each of us lives in a self‐reinforcing bubble. Our challenge is to reach through the membrane of our political world without breaking our connections with those closest to us.

Ecology: Mother Nature bats last

On Sunday, June 27, 2021, the Canadian village of Lytton, British Columbia, set a temperature record of 116 F (47 C). On Monday, it hit 118 F (48 C). On Tuesday, it set a national record of 121 F (49 C). Then, on Wednesday evening, a fire broke out that burned 90% of the town to the ground. Lytton’s week from hell was a stark reminder of what we have in store amidst a changing climate.

Solving the climate puzzle is perhaps the greatest collective challenge ever faced by humanity. Technological growth over the first three industrial revolutions has brought immense wealth, immense destruction, and a world‐historical crisis. It is as if an impetuous demon is testing humanity: “I’m going to put all this useful stuff in the ground. But I’m not going to leave enough room for it in the atmosphere. Let’s see what happens.”

“By the middle of this century, mankind had acquired the power to extinguish life on Earth. By the middle of the next century, he will be able to create it. Of the two, it is hard to say which places the larger burden of responsibility on our shoulders.”

Christopher Langton, 198719

Climate change gets—and deserves—top billing. Like no other issue, the changing climate highlights our interconnections, our injustices, and our insufficient action. But let us not forget other ecological issues: the pollution of water, air, and life itself; the degradation of soil, habitats, and ecosystems.

Historians and anthropologists have repeatedly shown that environmental change often preceded societal collapse.20 Sometimes this environmental change was beyond the control of the soon‐to‐collapse human community. They fell to volcanos, earthquakes, or storms. But in many cases, it was the choices of that community that led to their own downfall, whether by overfishing, deforestation, or polluting their water supply.

Technology and population growth have supercharged our ability to degrade the ecosystems upon which we depend. Change comes faster, and we have less time to adapt to the new ecological context we ourselves have created.What’s more, environmental issues have become truly global. Greenhouse gases do not have a nationality, and decisions made in Detroit or in Beijing affect the entire planet. The usage of fertilizers has transformed global agriculture, fed the world, and created global nitrogen and phosphorus crises. And, in a crisis that may soon become acute, the overuse of antibiotics is rapidly contributing to the microbes resistant to all the medicines we can throw at them.

If only the impacts of environmental degradation were distributed evenly. But environmental destruction weighs more heavily upon certain groups. In the United States, we see this clearly through the dimension of race. The evidence is clear: communities of color face a far greater burden of air pollution, poor water quality, and household toxins.21 In the United States, Black and Brown neighborhoods simply have fewer trees. Around the world, the poorest countries—those least responsible for the problem—tend to face the worst impacts of climate change.

In all of this, we can despair at the injustice. And we should. But let this also be a clarion call for facing the ecological challenges that tie us together.

Politics: Power spread and clustered

The once unstoppable march of capitalism and democracy has shown itself to be decidedly stoppable. China’s unique political and economic system has proven to be not only an engine of global growth, but resilient to global pressure—indeed, expectations—that it would shift towards the model of Western capitalist democracy. Across the globe, we have seen the rise of new forms of authoritarian government, often powered by populist and ethno‐nationalist narratives.

Even as some countries have gained power, we have seen a relative weakening of the nation‐state as the organizing principle of global society. Since the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, the world has been a collection of countries. And the country remains the substrate of global politics. But now we’ve also seen an explosion of non‐state actors. Transnational corporations operate at the scale of national governments, alternately facilitating destruction at a global scale and serving as beacons of responsibility. Terrorist networks like Al Qaeda have shifted the contours of history. Organized crime networks like the Sinaloa cartel in Mexico or the ‘Ndrangheta in Calabria alter politics and economies.

“In a time of drastic change it is the learners who inherit the future. The learned usually find themselves equipped to live in a world that no longer exists.”

Eric Hoffer22

And through all of this, civil society organizations have emerged as a force. Whether a giant global network like Oxfam or Greenpeace, or a small village cooperative in Peru, these organizations have institutionalized the work of social change. Spanning the political spectrum, a range of different strategies, and a full set of social issues, these organizations have made the work of doing good part of the very structure of society.

More broadly, our assumptions about the roles of different institutions in our society are in flux. For‐profit corporations face pro‐social demands from customers, employees, and investors. Companies can no longer speak only of shareholder value. The very allocation of financial capital has been reset by the emergence of the multi‐trillion‐dollar socially responsible investing market.

Nonprofit organizations have built business models that are often the envy of the business community, with trillions of dollars of annual economic activity in the U.S. alone.23 Society faces a promising but profound question: where does business end and social change begin?

Government roles have shifted as well. Sovereign wealth funds are some of the world’s biggest investors. State‐owned enterprises dominate entire sectors.24 In many countries social services are outsourced to either for‐profit or nonprofit organizations. The countless campaigns run to alter corporate behavior can be seen as a type of outsourced regulation.

“There are in history what you could call ‘plastic hours.’ Namely, crucial moments when it is possible to act. If you move then, something happens.”

Gershom Scholem 25

All of this adds up to a social contract in flux. Once‐stable assumptions about the roles of different institutions shift and crack. For the social change agent, this presents both a challenge and an opportunity.

It is undoubtedly a challenge to plan how to make a better world in the midst of such shifting sands. But it also creates an opportunity for growth, innovation, and nonlinear change; openings emerge in times of flux.

Acting in a plastic hour

Let us summarize this early‐21st‐century moment. Earth’s ecosystems are on the brink of radical change or even collapse. Multiple technologies are transforming our very understanding of life. Human culture is fragmented, yielding ineffectual politics unable to come to grips with the challenges before us.

The systems of the world are shaken; components are loose, floating, and disconnected. But just like when a Lego set is broken into pieces, it is possible to build something new from the fragments. Instability offers opportunity. Perhaps the structures of society are ripe for change.26 (In the Complex Systems chapter, we will develop a language—equilibrium, feedback loops, and tipping points—to help us think through how to act strategically in a system out of balance.)

The author Arundhati Roy described the COVID‐19 pandemic as a “portal.” She challenged us to decide what we brought with us as we passed through: “We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.”27

Our window of opportunity remains open: perhaps this plastic hour is a plastic century. As long as our world continues to change, it will be susceptible to the will of those of us who would act. One thing is certain: this is a consequential moment in the human story—an era where our choices will matter for generations to come.28

“If I had no choice about the age in which I was to live, I nevertheless have a choice about the attitude I take and about the way and the extent of my participation in its living ongoing events.

To choose the world is…an acceptance of a task and a vocation in the world, in history and in time. In my time, which is the present.”29

Thomas Merton

“There is always a well‐known solution to every human problem—neat, plausible, and wrong.”

H.L. Mencken30

Seeing the moment clearly

We face a situation too complex for any of us to fully understand. If we organize our work through any single lens, we are almost certain to stumble upon the complexity around us. A given perspective might be morally neutral, but it is not strategically neutral. Each lens focuses our attention on some things and blinds us to others. Consider how different forms of media promote different ways of thinking: the political repercussions of social media are different from those of radio. Similarly, each strategic framework tends to tilt us towards a given way of thinking and thus way of acting.

We do not have to look far to see the limitations of narrow ways of thinking about the world. The siloed institutionalization of the U.S. intelligence community rendered it incapable of recognizing the danger presented by Al Qaeda in 2001. The 2008 Financial Crisis was an inevitable consequence of applying a market lens to every aspect of life. Compelling business narratives like WeWork31 fell under the crushing weight of arithmetic. Countless nonprofits have brought a narrow solution to a complex problem—and failed.

Each of these failures was a consequence of the narrow application of one perspective on a complex world. As social change agents, we have an opportunity—and an obligation—to step back, take a breath, and do better.

In the next two chapters, I’ll offer frameworks for social change strategy and ethics. Then we’ll dive into the nine tools themselves.

I recognize this may seem like a lot to keep in your mind. But this multiplicity is the point. The human mind is a pattern recognition machine. When we seed our minds with patterns, we prepare ourselves for an unpredictable future. The age of flux demands a range of tools.

When you go to the eye doctor, they often sit down in front of a big metal machine called a phoropter. The optometrist cycles through a range of possible lenses—two at a time—and asks you, “Which is better: one or two?” That process helps find the right prescription for you.

Similarly, this book is meant to offer you a range of options to “try” in our complex world. It is up to you to choose which offers you the greatest clarity for thinking and acting in this plastic hour.

The 2020 California wildfires were a collision of intersecting crises.

Photo by Noah Berger

Clock of the sky, you measure the celestial eternity, one white hour, one century sliding on your snow, meanwhile the earth, entangled, is humid, warm: the hammers hit the tall ovens burn, the petroleum shakes in its plate, man searches, hungry, for matter, he corrects his banner, siblings gather, walk, hear, cities emerge, bells sing in the heights cloths are woven, transparency jumps onto the crystals.

Pablo Neruda

Age of Flux Takeaways

- If we deny the real progress the world has made, we insult those who fought for it; if we ignore the challenges of the world, we betray ourselves and future generations. History is contingent; it flows from our actions and from the forces that surround us.

- As we try to change the world, our predicament is constant, accelerating innovation constrained by increasing interconnection and complexity.

- A time of change is the perfect time to make change. Flux creates space for growth, innovation, and nonlinear change. In instability there is opportunity.

Notes

- 1 “An Intellectual Entente,” Harvard Magazine, September 10, 2009.

- 2 Chang (2019), pg. 180.

- 3 For more good news, see: https://www.vox.com/2014/11/24/7272929/global-poverty-health-crime-literacy-good-news

- 4 From “Monomyth.” Gorman (2021), pg. 191.

- 5 https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/17-statistics-world-statistics-day-and-why-we-need-invest-them

- 6 https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/17-statistics-world-statistics-day-and-why-we-need-invest-them

- 7 https://www.worldometers.info/

- 8 https://plasticoceans.org/the-facts/

- 9 https://www.worldometers.info/

- 10 https://www.sentencingproject.org/criminal-justice-facts/

- 11 Butler, Octavia E., The Parable of the Talents, pg. 72. Grand Central Publishing Reprint Edition, August 20, 2019.

- 12 Laudato Si, Chapter 1, Paragraph 18.

- 13 “From the Chairman: The Pace of Change.” Joint Forces Quarterly, January 26, 2017. Quoted in Wood, David. “We Need a Slow War Movement.” Backbencher, March 16, 2021.

- 14 Chakravorti (2003).

- 15 Quoted by Hugh Raffles in The Book of Unconformities: Speculations on Lost Time. Pantheon Books, 2020.

- 16 Nearing, Helen and Scott. Living the Good Life, pg. 39. Shocken Books, 1954.

- 17 Toffler, Alvin. Future Shock, pg. 2. Bantam Reissue Edition, June 1, 1984.

- 18 Our fragmentation is not just a virtual phenomenon. A spatial dynamic helped build our islands of belief. In the United States, this has come to be known as the “Big Sort”—the physical relocation of people to neighborhoods full of people just like themselves. This geographic division complicates basic human communication, not to mention the work of changemakers.

- 19 Artificial Life: Proceedings of an Interdisciplinary Workshop on the Synthesis and Simulation of Living Systems. Pg 43. From a workshop in 1987 hosted by Los Alamos National Laboratory and co-sponsored by the Center for Nonlinear Studies, the Santa Fe Institute, and Apple Computer Inc. Later published as a book by Routledge in 2019.

- 20 See, for example, Jared Diamond’s Collapse. Penguin, 2011.

- 21 For a discussion of the link between pollution and discriminatory housing practices see, “Redlining means 45 million Americans are breathing dirtier air, 50 years after it ended” by Darryl Fears in the Washington Post, March 9, 2022.

- 22 Reflections on the Human Condition (1973). (Quoted in Stein Greenberg 2021.)

- 23 See https://candid.org/explore-issues/us-social-sector/money

- 24 In China, you even see influential GONGOs, “government organized nongovernmental organizations.”

- 25 Quoted by George Packer in “America’s Plastic Hour is Upon Us.” The Atlantic, October 2020.

- 26 Recent science has demonstrated the human brain’s extraordinary capacity for change—a phenomenon known as “neuroplasticity.” Old dogs can, in fact, learn new tricks. Perhaps human society can show a similar capability, a socioplasticity.

- 27 Roy, Arundhati. “The pandemic is a portal.” Financial Times, April 3, 2020. I cannot help but to note another dimension to Roy’s remarkable metaphor. In physics, “flux” is defined as a volume passing through a surface over a given amount of time. As we think the “flux” of a changing world, the equations of science match her image of passage through a portal.

- 28 Serious thinkers have suggested that the 21st century may be the most important in history. See, for example, https://www.cold-takes.com/most-important-century/

- 29 Merton, Thomas. Contemplation in a World of Action, pg. 149. University of California Press, 1968. Quoted in Odell (2019), pg. 59.

- 30 From Prejudices: Second Series, pg. 155. Alfred A. Knopf, 1920.

- 31 Brown, Eliot and Maureen Farrell. The Cult of We: WeWork, Adam Neumann, and the Great Startup Delusion. Crown, 2021.