Introduction

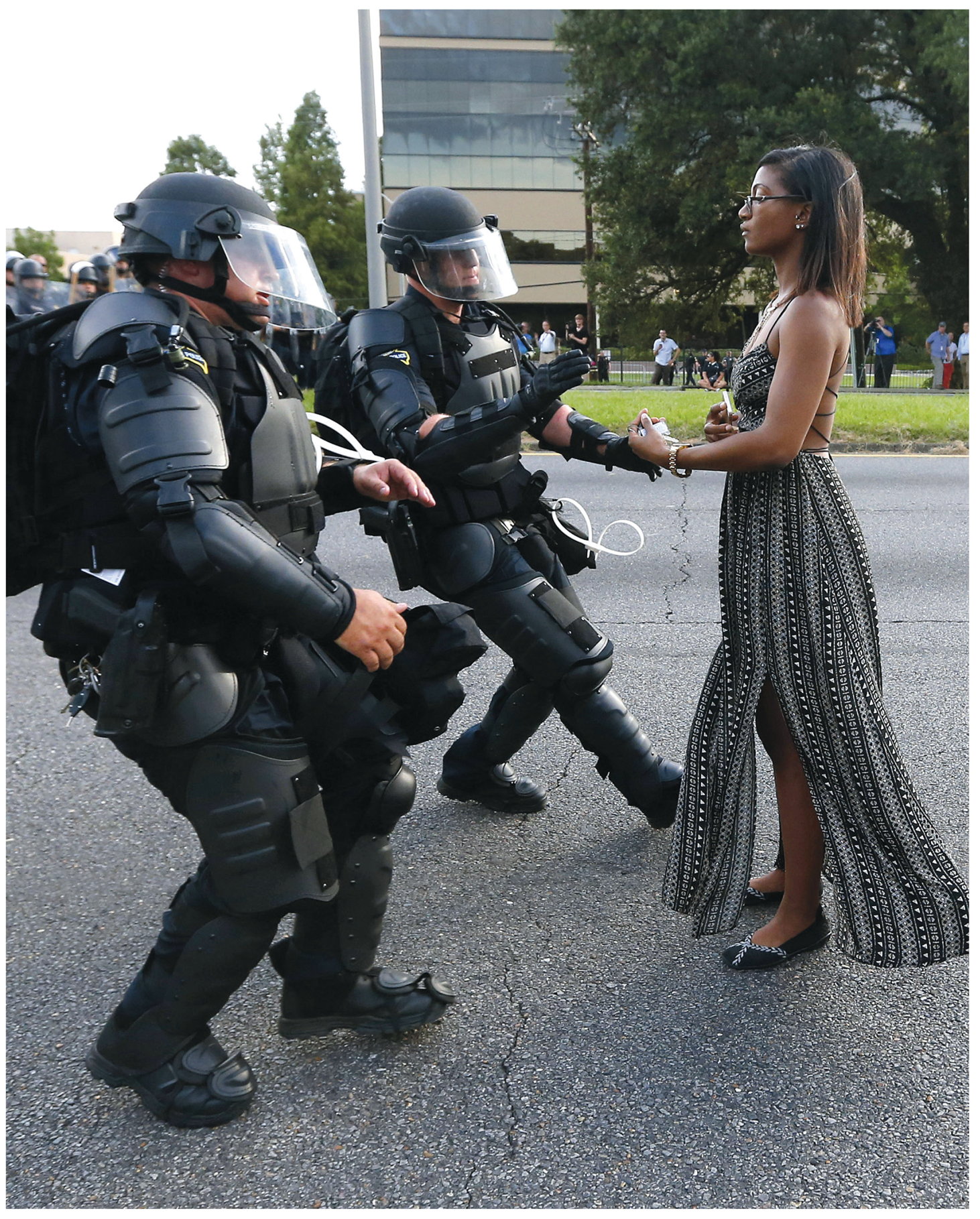

Ieshia Evans protesting the murder of Alton Sterling on July 9, 2016, in Baton Rouge, LA.

Photo by Jonathan Bachman

“Let’s check to see if the ground is okay.”

Kids tumble, knees scrape. As a toddler, when I’d trip and fall, my mother would scoop me up. She’d give me a kiss and a hug. Then she would turn our shared attention to the spot where I fell. My mother would kneel, place her hand upon the earth, and ask us to show compassion to a scrap of land: “Let’s check to see if the ground is okay.”

In part, this was a young parent’s practical trick to distract a crying child from passing pain. But it was more.

My mother’s strategy manifested a deeper belief: kindness is infinite. We have enough kindness for a world that has held us up, even enough for a world that has hurt us.

That kindness powers the greatest of human impulses: to serve, to build, to love, to witness.

It drives us to seek a better world—to multiply justice and joy.

But change is hard. The world does not easily yield to our visions of perfection.

How do we make change?

There are no easy answers.

Instead, there are tools.

The work of social good is spread throughout society. Its burden falls upon the shoulders of people with and without power. Its challenges fall to those with formal training and to those who simply dream of something better.

It starts within the radius of community. One neighbor picks up trash along the sidewalk; another takes food to the homebound. The circle grows as people patch up the gaps in society from within the walls of a clinic or a school. Others build something fundamentally new, creating new products, new inventions, new art, and new institutions. Still others seek to change the systems that already exist—as executives on the inside or as activists on the outside.

Sometimes the change is part of a conscious vision; other times circumstances simply make it necessary. In a community hit by a natural disaster, people open their houses to neighbors who lost theirs. In a pandemic, fire chiefs transform fire stations into testing centers. In the midst of poverty, school administrators figure out how to feed a neighborhood so that they can educate it. A CEO looks out from a corner office window on a sea of demonstrators and realizes the time has come to confront the company’s carbon footprint.

“You imagine a circle of compassion, and you imagine no one standing outside of it.”

Father Gregory Boyle1

The path to something better is rocky, steep, and difficult. We quickly learn the limits of our understanding. There is no one single answer; there is no one technique; there is no silver bullet.

Let’s all say it together: if all you have is a hammer, the whole world looks like a nail. Narrow strategies invariably stumble against the complexity of the world.

Alas, the work of social change is full of people with hammers. I have been as guilty as any. In my days as a grassroots organizer, I thought that bottom‐up activism was the only way to make authentic change. In business school, I looked to markets for the possibility of scale. Working in philanthropy, I viewed decision‐making through the lens of behavioral economics. When leading a technology platform, I used the frame of complex systems science to formulate our strategy.

How might we judge my strategic promiscuity? We might say I was always naïve, distracted by the latest shining object. Or we may say I was—unknowingly, perhaps—partially right each time. In fact, each tool offered a unique perspective for understanding—and acting in—the world. The complexity of the world forced me to assemble a toolbox that worked for me.

I wrote this book because agents of change need a toolbox strategy. By “tools” I mean frameworks for thinking and acting. By “toolbox” I mean an individual’s collection of tools. And by “toolbox strategy” I mean an approach that brings multiple tools to complex problems.

In this book, we will—in a structured way—explore a set of nine tools that can help us build the better world we seek.

These tools have driven world‐shaking social movements and billion‐dollar businesses. But they are just as relevant for a neighborhood association or a farmers’ market.

The nine tools do not represent every possible perspective on strategy impact strategy. But, together, they offer a mosaic view, a toolbox strategy for change.

“We need a multitude of pictures about the world…

a gentle jeremiad against theoretical monism.”

Kwame Anthony Appiah2

Storytelling is the human impulse to understand the world through narrative.

Mathematical modeling is the essential practice of putting numbers to our assumptions.

Behavioral economics offers insights into human behavior as it is, not as we wish it to be.

Design thinking puts the user at the center of any process or challenge.

Community organizing is the art of building people power.

Game theory is a rigorous way to align our decisions with those of other people.

Markets represent the primary mechanism of resource allocation in our world.

Complex systems teaches how the whole can be greater than the sum of its parts.

Institutions form the essential infrastructure of our society.

Signs of wear are signs of use

Signs of use are signs of necessity

Necessity and use are

Signs of love

Rūta Marija Kuzmickas

The structure of this book

The Black feminist scholar Audre Lorde famously said, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”3

She argued that attitudes and systems of oppression cannot simply be turned against the oppressor. We must apply new approaches to solve old problems, otherwise, “only the most narrow parameters of change are possible.” This is a warning that should echo in our minds.

Luckily, the tools in this book do not belong to the master. These tools are the common heritage of humanity. The question is, how do we choose to wield them? What purpose and what moral frameworks do we bring so that we may rebuild a house for everyone?

This book is meant to offer a hand to those on this fraught and thrilling journey. It is, admittedly, a hybrid: part textbook and part pep rally.

But mostly, it is meant to seed your intuition as you face the unknown ahead.

Throughout, I’ve included stories, poems, quotes, diagrams, photos, and equations that represent a range of possibilities for social change. Some will resonate with you, others may not. That is the point.

You can think of the first three chapters as the “box” and the next nine chapters as the “tools.” In Chapter One, we’ll explore our early‐21st‐century context and why a toolbox strategy is necessary.

Chapter Two provides a basic language for thinking about strategy. Chapter Three explores a set of moral and ethical dynamics that complicate and enrich the work of social change.

Then, the nine tools. Each of the tool chapters will explore a tool in depth, laying out its basic presumptions, concepts, and vocabulary. In each case we will explore times when this tool is appropriate and when it is not. And, for those ready to go deeper, I’ll suggest more resources.

There is no chapter with architectural drawings for the perfect society. The tools in this book are just that: tools. They do not provide boldness, vision, or moral clarity. These tools must be brought to life by the force of human action. When the book closes, the rest is up to you.

“For the vanguards of the present dreaming up new ways to fight global warming or Black Lives Matter activists seeking alternatives to policing as we know it, this is an essential point: that the shape and extent of the change they seek depends as much on what tools they use as it does on their own will and hunger.”

Gal Beckerman4

Commonalities and mindsets

The nine tools are not isolated or distinct; they overlap and intertwine. Throughout this book, you’ll find common themes like listening, risk, power, information, and interconnection. (To highlight some of these commonalities, you’ll find color‐coded “hyperlinks” that show connections across chapters.)

A social change agent doesn’t have to pick one single tool to solve one problem.

Instead, the essence of toolbox strategy is multiplicity: there are many ways to understand and many ways to act. Our complex world asks us to go beyond our single hammer, and it is possible to do so.

Let me suggest four foundational mindsets to help you navigate the range of ways of thinking about social impact strategy.

The first is to open yourself to a “both/and” mentality. Toolbox strategy does not choose between qualitative or quantitative; it uses both the quantitative and the qualitative. Toolbox strategy is not limited to gradual change or to revolution; instead, it sees power in both the incremental and the disruptive. Toolbox strategy is not limited to radical outsiders or ambitious insiders; it recognizes the possibility of change both inside the system and outside the system.

Second, recognize the power of clarity. Clarity short‐circuits confusion and enables collective action and learning. A clear hypothesis is more useful; direct communication is more effective. Clarity does not mean arrogance. Humility is itself a type of clarity. Sometimes the best way to equip ourselves for reality is to be honest about our own ignorance.

Third, experiment with understanding. We can explore which ways of thinking are most useful for a given problem. You can “try on” a given mindset or framework and see where it leads you. Then try another.

Draw lessons according to how useful they are.

Finally, and most importantly, the right thing to do is the strategic thing to do. Even as you experiment with understanding, hold fast to your values. Human virtue offers a stable foundation for strategic creativity. And it works. Honest, compassionate behavior ultimately builds trust. Trust builds connection. Connection builds power. The most important piece of news in this book is this: kindness can be strategic, and strategy can be kind.

“Service is the rent we pay for being.”

Marian Wright Edelman5

Language

The vocabulary of social good can be unsatisfying. We are stuck using words like “nonprofit” or “non‐governmental” that are defined by a negative. Simple ideas end up conveyed through a complex stew of acronyms. (In the Markets chapter, we’ll go through ESG vs CSR vs PRI vs SRI.)

This linguistic reality reflects a changing society. People are trying to sort out a new, cross‐sector vocabulary for social good. This aspiration gives me hope, but it undoubtedly makes communication harder.

In this book, I’ve tried to use the words we have instead of making up new ones.

Where appropriate, I’ll highlight important linguistic nuance. (For example, I will later discuss what I see as the difference between “social change” and “social impact.”) Other times, my word choice reflects an expansive view: “changemakers” or “social change agents” are just people working for a better world.

This generality is on purpose. Millions of people are positioned to do good in the world—and to do so in different sectors and at different scales. We cannot confine these lessons to nonprofit staff, social entrepreneurs, and philanthropists. Our world needs strategic action from nurses and pharmaceutical executives, accountants and tax officials, prime ministers and community gardeners.

I acknowledge the awkwardness of the social good lexicon. But let’s try to see this linguistic confusion as a reminder that millions of humans are in the middle of something important: they’re trying to figure out how to do good, together.

The power and limitations of perspective

Before I close this introductory chapter, I should say a few words about myself—and the strengths and weaknesses of my own perspective.

First, the weaknesses. Most fundamentally: I am only one person. My life has offered one perch from which to understand our shared complexity.

Further, on almost every dimension of my identity—race (white), gender (male), sexual orientation (straight), citizenship (U.S. citizen)—I find myself in a privileged caste. This privilege has given me access and opportunity that I have tried to use for a greater good. And it has surely blinded me to realities that are obvious to others.

While I’ve had deep engagement with business and government, most of my work has been in the nonprofit sector. I’ve worked in many countries but have lived most of my life in the United States. I try to be conscious of these limitations, and readers should, too.

The man pulling radishes pointed the way with a radish.

Kobayashi Issa

Now, the strengths. I’ve been blessed to spend two decades working for a better world. I’ve felt the sting of tear gas and the cut of handcuffs. I’ve sat in seats of power: in elite boardrooms and on the stages of august conferences. I count myself lucky that I’ve been able to work within some of the most influential, innovative, and impactful organizations in social change, from Greenpeace to Bridgespan to the Hewlett Foundation.

Over the past decade, I’ve had the privilege of serving as CEO of GuideStar and to lead its 2019 merger with Foundation Center to create Candid, which Fast Company called “the definitive nonprofit transparency organization.”6

These roles have been a blessing, not least because they have given me access to the lessons of a field. Ultimately, what is most important are not the organizations I’ve worked for but those I have worked with. My one perspective has allowed me to bear witness to the perspectives of so many others. Their tools—our tools—offer hope in an age of flux.

“The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present.

The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise—with the occasion.

As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew.”

Abraham Lincoln

December 1, 1862

Annual Message to Congress

Notes

- 1 “The Calling of Delight: Gangs, Service, and Kinship.” Interview with Greg Boyle. On Being. February 26, 2013. (Fr. Boyle has offered various versions of this quote elsewhere.)

- 2 As If: Idealization and Ideals, pg. x. Harvard University Press, 2019.

- 3 Lorde, Audre. “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” 1984. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, pg. 110–114. Crossing Press, 2007.

- 4 Beckerman, Gal. “Radical Ideas Need Quiet Spaces,” The New York Times, February 10, 2022.

- 5 See Wright Edelman (1992), section 1. She may have been referencing Muhammad Ali’s quote, “Service to others is the rent you pay for your room here on earth,” which he wrote in a note to the staff of the Atlanta Hilton on April 19, 1978.

- 6 Ben Paynter, “GuideStar and the Foundation Center are merging to form the definitive nonprofit transparency organization.” Fast Company. February 5, 2019.