2

What Have We Learned About Learning?

All organizations have to evolve to serve modern workers in a culture of continuous learning. But let’s first review why, specifically, traditional training programs are no longer adequate for today’s learning needs.

Historically, “workplace training” has had a bad reputation. And it’s not like this is a closely guarded secret. Just do a search for “bad corporate training memes” and you’ll see what I’m talking about.

So, why do so many of us have negative associations when we hear about employee training?

■ It’s mandatory. Of course, certain compliance trainings really are mandated by law, regulation, or policy. They’re the soggy, overcooked vegetables no one likes but everyone has to choke down. However, some companies go further and make other types of training compulsory. Any learning experience that’s rolled out uniformly to everyone is ultimately going to be useful to only a few. You can’t take shortcuts if you want engaged, motivated learners; so, no, you can’t create one-size-fits-all content.

■ It’s boring, static, passive, and outdated. There’s a reason lots of stock photos for “corporate training” show dead-eyed workers slumped at desks. Too much learning content feels as if it was created in another era, long before we became accustomed to interactive online experiences, on-demand video, and the countless sources of information (and entertainment) competing for our attention at work and at home. Do you really think an audience accustomed to the sensory feast of Avengers: Endgame is going to sit still for a tedious PowerPoint presentation?

■ It’s punitive. In some instances, training has been inflicted on employees who need to “fix” a shortcoming. Too often, performance reviews and evaluations are used to zero in on what employees are doing “wrong,” particularly in cultures where mistakes are viewed as personal failures rather than opportunities to learn and improve.

■ Training is doled out as a reward. In this case, only the “good” employees get to go. This is a broken narrative. Learning has to be seen as a must-have for all. Every employee, every level.

■ Outcomes of training are not always clear. When the outcomes of training are unclear or not compelling, senior executives question the value of investing in them. As a result, any training that does exist is a low-priority afterthought, and it feels that way for employees who have to sit through it.

Taking Learning and Development to the Strategic Level

Despite training’s dreary history, don’t fall into the trap of jumping from “training is broken” to “learning is pointless.” Learning isn’t the bad guy in this story.

We—management and employees—need to give HR teams the chance to show us they can have a bigger impact. At the same time, we must also acknowledge that L&D and 20HR aren’t one and the same, even if some of the personnel overlap.

The demands of the twenty-first century workplace require different approaches. It’s not about doing more. It’s about doing L&D better. So, no more mandatory, one-size-fits-all training sessions that interrupt the workday and force people to sit through boring content. Training has to be delivered in ways that make sense for busy workers who are used to consuming digital content all the time. That means self-paced, on-demand, and video based, preferably in bite-size chunks, so people can apply what they’ve learned to whatever they’re working on right now. And when you gather people together, make it worth it.

Moreover, we’ve learned a lot more about what makes for effective learning. The challenge is moving those insights from the learning science realm into the corporate setting. Don’t worry, you won’t have to become a PhD to accomplish that.

A Brief Foray into the Science Behind Learning

I started my career as a high school teacher in Canada and spent almost a decade in the classroom, mostly teaching Spanish and English. Like most people brand-new to a profession, I made mistakes. Lots of ’em. I remember spending hours inundating my students with material from overhead projector notes while they literally sat in the dark. Yes, an overhead projector (Figure 2.1). I had no idea what I was doing, I had no time to prepare my lessons, and I was pretty much on my own to figure it out.

FIGURE 2.1 OMG, remember this thing? How many of my students were asleep?

It didn’t take too long to see that my approach was not engaging my students or helping bring any of my teaching material to life. I came up with other methods and modalities that made more sense for my students, and pretty quickly I started to see actual learning taking place.

So, imagine my surprise and confusion when I transitioned to corporate training and discovered the learning function was still stuck in that overhead-projector mentality. In fact, there were a lot of lessons I had learned the hard way from my classroom days that fit perfectly into the office setting. Ironically, when I moved from teaching high school to the private sector, a well-meaning manager advised me to keep my teaching background on the down low; otherwise, my corporate colleagues might see me as “soft” from having spent so much time around children. I was also told my teaching experience “didn’t count” in the business world. (Ouch, that hurt.) But in short order, I found the situation to be just the opposite. Now, I am quite happy to talk about my classroom experience when I meet new employees, stand in front of a conference audience, or consult with corporate customers. It’s an important piece of my own career journey, and it is completely relevant to my place heading up L&D inside a learning company now.

Learning and development professionals, like everyone, are busy people moving fast. That doesn’t always leave much headspace to reflect on whether some ideas and approaches could be improved and updated. Sure, it will take hard work, 22but it will also open opportunities to show how workplace learning can make a strategic impact.

A ton of time, research, money, brainpower, and curiosity is put toward understanding how people learn and how we can use that science to improve traditional education experiences and outcomes. But, as I’ve discovered, we don’t become a new species of learner when we move out of the formal classroom and into the world of work. Following are some of the lessons I’ve brought with me from my high school teaching days that resonate strongly with my corporate learners.

Lesson 1: Necessity Is the Mother of Learning

Completion cannot be taken as a proxy for learning. In fact, checking boxes was never an accurate reflection of effectiveness. Training programs must have a clearly defined goal, measurable outcome, practical application, and ongoing value and relevance. Employees should never walk away from a course or workshop thinking they’re “done.”

People retain knowledge when they have an immediate need to apply it and ongoing opportunities to reinforce it. That’s why it works so much better for employees to seek out new skills when a real need arises that’s personally motivating, for example, gaining a new competency to succeed on a project or show they’re promotion ready.

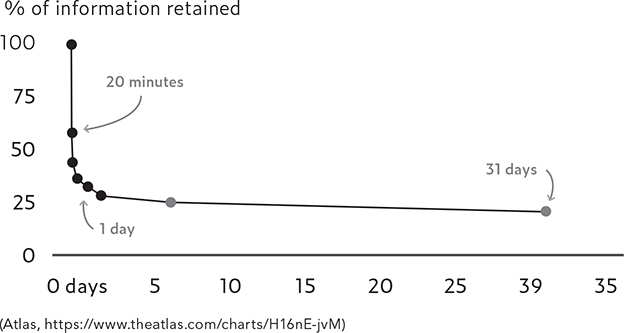

The German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus first researched and demonstrated the “forgetting curve” in the nineteenth century (Figure 2.2). Basically, he found that people forget most new information right away. But he also discovered people could retain more if they repeated the new information at regular intervals—that is, “spaced repetition.”1

FIGURE 2.2 Hermann Ebbinghaus’s forgetting curve

Beyond the finding that spaced repetitions produce more learning, neuroscience also reveals that longer spacings tend to produce more long-term retention than shorter spacings.2

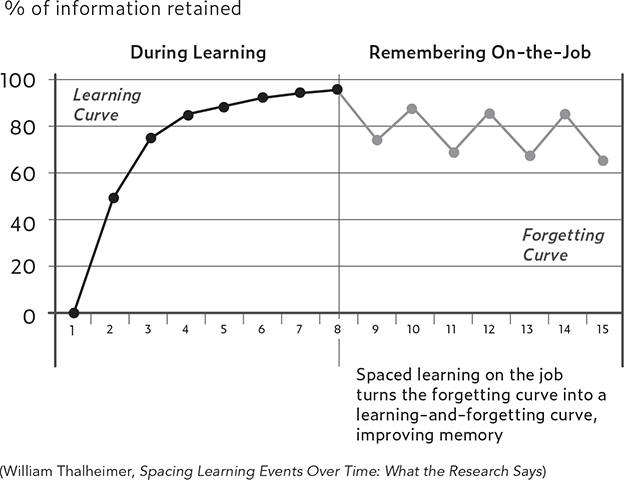

When people recognize their need to learn and continue using a new skill, they’ll see the benefit of repeated exposure and practice (Figure 2.3). Learning and development can establish the structures that empower an employee to engage in learning and repetition, but the student has to identify and prioritize what’s driving his or her need in the first place.

FIGURE 2.3 Learning and forgetting with spacing on the job

We’re often stuck thinking that spacing has to be as long as or as deep as that first touchpoint of learning, but research from Thalheimer again shows us that’s not necessarily the case. We don’t have to repeat a three-hour workshop to get the same value from the learning. We can explore the concept in new and different ways. He suggests that repetitions of learning points can include:

1. Verbatim repetitions

2. Paraphrased repetitions (changing the wording slightly)

3. Stories, examples, demonstrations, illustrations, metaphors, and other ways of providing context and example

4. Testing, practice, exercises, simulations, case studies, role plays, and other forms of retrieval practice

5. Discussions, debate, argumentation, dialogue, collaboration, and other forms of collective learning

The biggest takeaway is that we need to space out learning points, and to time learning events and spaced practice—whatever type it may be—as closely to the practice as possible.

Lesson 2: Pedagogy (or Andragogy) Must Be Prioritized over Novelty

Like every other line of business, L&D and HR people have their share of jargon, and they sometimes fall for hype and jump on shiny new trends just because they’re getting lots of buzz. Emerging technologies like virtual reality and augmented reality have exciting potential for learning, but L&D practitioners shouldn’t rush to embrace them without having solid instructional design and content first.

Indeed, a lot of what we’ve learned about learning is that concepts we used to accept as truths are no longer viewed as valid. It’s not a bad idea to see how new ideas and technologies play out before deciding they’re right for your team. Consider the concept of learning styles. For 30 years, teachers heard that every student had a preferred style of taking in new information—visual, verbal, auditory, and so on—and that, if instructed using the “wrong” style, the material wouldn’t stick. Then, in 2009, the Association for Psychological Science published a report debunking the research behind learning styles and declaring its conclusions not credible.3 Does that mean you should wait 30 years before adopting a new technology to be sure of its veracity? Of course not. But we all need to do our homework before introducing new technologies and tools.

No less a tech luminary than Bill Gates has said we shouldn’t assume technology holds the solution. As he told the Chronicle of Higher Education, the approach of simply giving students tablets or other devices to use in their existing environment has a “really horrible track record.”4 Richard Clark, professor of educational psychology and technology at the University of Southern California, published a definitive study showing that pedagogy (i.e., teaching practice), not medium (i.e., technology tools and resources, such as whiteboards, handheld devices, blogs, chat forums), makes all the difference in learning effectiveness. Clark asserted that instructional media are “mere vehicles that deliver instruction but do not influence student achievement any more than the truck that delivers our groceries causes changes in our nutrition.”5

Here’s the point for corporate trainers and instructional designers to keep in mind: You must start with a crisply 27defined learning goal. Then, choose the best delivery method for achieving that goal. That might be a slick tech interface, but it could just as easily be a social learning program that consists of employees simply discussing a topic and learning together.

Lesson 3: You Are Responsible for Creating the Energy in the Room

I stole this one from Oprah Winfrey, but as is so often the case, she said it best: “You are responsible for the energy that you create for yourself, and you’re responsible for the energy that you bring to others.” Standing in front of a classroom of teenagers: so true!

There’s a lot you can do to set the right mood in the physical spaces where learning happens. Effective L&D can’t take into account only the training content itself; you have to consider environmental factors that contribute to or detract from successful learning. This includes everything from the physical space itself (room layout, temperature, music, lighting) and materials presented (slide design, participant guide, handouts) to attendees’ bodily needs (snacks and breaks) and emotional considerations (relationships, anxieties).

Not surprisingly, many of us find it hard to stay alert and engaged when we’re trapped inside a bland conference room for hours or days on end. It even makes a difference what the room temperature is, whether there are windows, what colors are on the walls, and so on. One study found a 26 percent increase in performance on math and reading tests among students who were exposed to more natural lighting.6

I’ve carried over a lot of helpful nuggets from the classroom to the corporate training room. Here’s a little more about each:

■ Physical layout. Are you trying to facilitate independent work? Breakout groups for collaboration? Discussion among the entire audience? Might there be employees engaged in different parts of the training but still in the same room? All those considerations will affect something as simple as how you arrange tables and chairs.

■ Music. My team actually creates playlists to get learners in the right headspace before the session begins, to keep them energized during break times, and to wrap up at the end on (literally) the right note.

■ Presentation materials. When confronted with endless, jam-packed PowerPoint slides, people’s eyes glaze over. It’s not their fault. Our brains can only handle so much cognitive load before we tune out. In short, if it takes too much effort for us to process and store information, we won’t learn successfully.

Smart instructional design can ease the cognitive load on learners by taking into account the very real limits of our working memory. Distractions take a huge toll on our cognitive energies, which is why you should ban smartphones and even computers if they’re not required for the training.

Strong instructional design also creates the conditions for powerful learning. As a teacher, I was introduced to the concepts of scaffolding and the zone of proximal development. The latter concept, credited to psychologist Lev Vygotsky, addresses the gap between what learners can achieve on their own and what they can achieve with encouragement and guidance from an expert.7

Vygotsky’s work also asks us to think about how we layer and build out information to teach others. To ensure learners are supported throughout the process, we have to meet them where they are, add to and acknowledge their existing knowledge, and guide them through expanding on that knowledge. Scaffolding is a great metaphor for the ancillary activities led by a trainer or subject-matter expert to support students as they navigate the zone of proximal development. Scaffolding is like training wheels on a bicycle that keep riders upright but can be removed once they’ve gained the confidence and competence to ride independently.

As my team will attest, I also pay close attention to the look of the learning content we create. It doesn’t matter if we’re producing online video-based courses, slide decks, or handouts, we strive to follow design principles that are conducive to learning.

I’m a huge fan of communications expert Nancy Duarte and her books on visual presentation design. I keep ordering more and more copies of her slide:ology: The Art and Science of Creating Great Presentations as new people join our team because her design principles help us ensure that learning efficacy takes center stage and is bolstered by the design.8

I’m also a sucker for incorporating a symbolic visual motif to deepen the learning. Our self-advocacy workshop uses a Rosie the Riveter theme to convey the idea of empowerment, and our Career Navigator workshop riffs on mountain imagery to represent peak career experiences. These visual metaphors create memorable and positive associations for students as they revisit and reflect on what they’ve learned.

Lesson 4: Fear Is the Learning Killer

Okay, an Oprah quotation is no surprise, but how about author Frank Herbert offering up this wisdom in his sci-fi classic Dune: “Fear is the mind-killer. Fear is the little death that brings total obliteration.”

As I’ve mentioned, not everyone approaches learning activities with confidence and enthusiasm. Linguist Stephen Krashen studied the factors that affect someone’s ability to learn a new language, and one of his hypotheses was around the so-called affective filter. If a student’s affective filter is up because they’re embarrassed or feel judged, Krashen posited, his or her ability to acquire language is constrained.9

This is just one more reason that L&D must start by building relationships based on trust throughout the organization. I learned this as a language teacher, as I saw students shutting down out of fear, embarrassment, or anxiety. I took great pains to reduce those feelings—telling stories of my own language learnings and focusing on small achievable goals.

These same fears and anxieties appear in the adult setting and can often be amplified. We’re done with school now, right? We’re supposed to have it all figured out. But when people feel that spotlight on them, the feeling that they don’t know something can shut down the conditions for learning. Great L&D practitioners understand this and know they need a high degree of emotional intelligence to stay attuned to how learners are feeling and how to interpret what they’re saying and what they’re not saying.

But fear doesn’t have to come from within. Here, I’m specifically talking about high-performance work cultures in which people believe they’re expected to be perfect. They are afraid to take risks and fail publicly, so they play it safe and try to stay out of trouble. Learning cannot happen under these conditions.

Companies have to create a culture in which it’s okay to make mistakes—and talk about them. That comes from encouraging a growth mindset in every employee. I’ll explore more about this foundational work of Stanford University professor Carol Dweck in Chapter 5, but the gist is this: We all have the capacity to learn and grow, but we have to understand that it’s a process, not an outcome or goal. We only improve when we push through the discomfort of trying, failing, and trying again. Dr. Brené Brown says something similar: Letting yourself be vulnerable takes courage, and it can be painful. But when you get up again after a setback, you grow and you get better.

If yours is a culture dominated by fear, where employees are reluctant to speak up about problems and challenges, people won’t be able to learn and develop.

Lesson 5: Don’t Make a Fish Climb a Ladder

Last quotation for now, this one often attributed to Albert Einstein (not everyone agrees), and it gets thrown around a 32lot in education circles: “Everyone is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.”

Regardless of who said it, it’s true, and it’s important. We can’t measure all our learners by the same criteria, nor can we deliver on their learning needs the same way. Individuality is our strength, so let’s not fight it. Sure, there are occasions when you want the whole organization swimming in the same direction. You’re probably well aware of those. But you’ll quickly discover—when you’re making connections and forming relationships, when you get responses to your posttraining surveys, when managers regularly have career development conversations with their direct reports—there are many instances when our individual differences need to drive the experience.

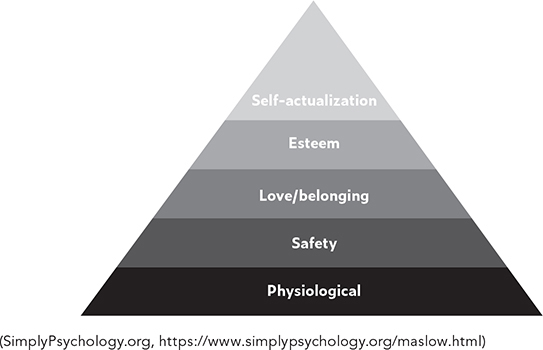

When we think about how to develop our employees, the focus needs to be on strengths, not weaknesses. Psychologist Abraham Maslow developed the hierarchy of needs to describe the stages of human growth (Figure 2.4). You’re likely familiar with this theory, which has reached the mainstream as the mindfulness movement continues to gain steam.

FIGURE 2.4 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

At the top of Maslow’s pyramid is self-actualization, which is the idea that individuals seek to be the best versions of themselves. We get there via continuous self-improvement. But as the hierarchy shows, other conditions must be satisfied before we can achieve self-actualization. For example, we first need to feel safe, have a sense of social belonging, and believe in ourselves. As we’ll discuss, L&D practitioners are instrumental in fostering workplace conditions that will satisfy those needs.

Maslow also formulated the theory of having peak experiences,10 moments of pure joy felt by those who’ve achieved self-actualization. Individuals having a peak experience will feel that they:

■ Have lost track of time and space

■ Are a whole and harmonious self, free of dissociation or inner conflict

■ Are making full use of their capacities and capabilities and reaching their highest potential

■ Are functioning effortlessly and easily without strain or struggle

■ Are totally in command of their perceptions and behaviors

■ Are without inhibition, fear, doubt, and self-criticism

■ Are spontaneous, expressive, and “in the flow” of whatever they’re doing

■ Are open and receptive to creative thoughts and ideas

■ Are present in the moment and uninfluenced by past or expected future experiences

■ Are experiencing pleasant physical sensations

Peak experiences sound awesome, don’t they? But when we ask fish to climb a ladder, we’re taking them away from the place where they can shine and, therefore, away from self-actualization and peak experiences. As L&D professionals, we can’t ignore areas that need improvement, but we also have to let a fish be a fish.

For example, it’s reality that career paths are no longer linear. People are exposed to a lot more opportunities and 36options, and it’s perfectly acceptable for people to decide they’re interested in pursuing something different from what they’re doing now or what they once aspired to. What is an L&D practitioner to suggest to an eager, motivated employee who wants to move into a new area of work?

At Udemy, our own product uses artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to recommend what courses employees should take now—and take after that. These recommendations are based on trends and behaviors exhibited by other platform users who’ve expressed an interest in the same learning topics. We can even match them with instructors similar to others they’ve liked in the past.

It’s now within our reach as L&D professionals to facilitate personalized learning experiences using tools like differentiated instruction (tailoring experience to individual needs) and adaptive learning, powered by technologies such as machine learning and AI.

Don’t force a square peg into a round hole, and don’t make an employee sit through sessions that are irrelevant or out of context.

Lesson 6: Learners Need to Put Some Skin in the Game

It’s a challenge to keep students fully engaged over the long haul. To do that, you’ll need to get creative with rewards and incentives for extra motivation. Gamification is a topic near and dear to me (I wrote my master’s thesis about it), and it works when done right.

We weave gamification into many of our initiatives at Udemy to encourage people to put some skin in the learning game. As members of a learning company, of course, our employees are more predisposed to pounce on L&D offerings than workers at other organizations, perhaps, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have to work for it too.

Gamification is often oversimplified to the idea of giving out prizes or turning everything into a competition, but it’s much more than that. Gamification is the use of game mechanics and experience design to engage and motivate people to change a behavior or achieve a goal. That might mean developing an actual game—which is something we have done at Udemy and will discuss in Chapter 6—but there are other, less obvious ways to gamify a learning experience to make it more compelling and engaging. In fact, plenty of products or apps you use every day leverage gamification techniques.

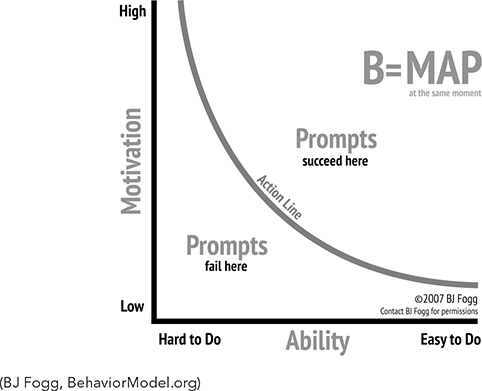

Software companies have gotten particularly good at gamification. I’ve always been a fan of BJ Fogg, the founder and director of the Stanford Behavior Design Lab, and his work on persuasive technology. He talks about how technology can adapt or motivate a behavior, which is a useful way for L&D practitioners to think about how to begin designing gamified experiences. Fogg also came up with his B = MAP model,11 which examines how motivation, ability, and prompts must work in concert to produce a behavior (Figure 2.5).

FIGURE 2.5 Fogg Behavior Model

When we design gamified learning experiences for employees at Udemy, we think about the behavior we’re trying to instill. Then we dig deeper into our learners’ motivations and abilities to determine how strong a trigger, or prompt, is needed to produce action. As Fogg concludes, we need to think of all these factors together to influence behavior.

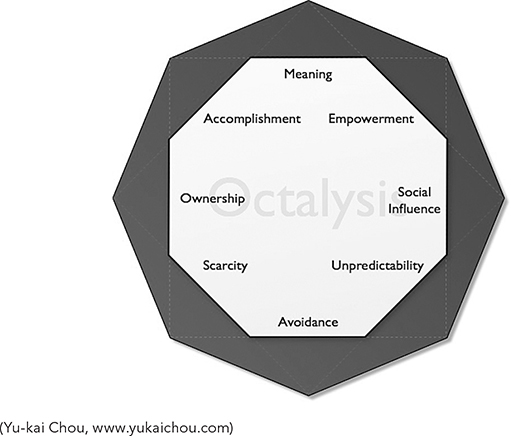

I also like Yu-kai Chou’s Octalysis framework for gamification,12 which identifies what he calls the eight “core drives” of human motivation (Figure 2.6). These include things like meaning (finding greater purpose), accomplishment (overcoming a challenge), and social influence (wanting to match or outperform others). It’s important for leaders to understand these drives in order to provide the right motivation for the individuals on their teams.

FIGURE 2.6 Yu-kai Chou’s Octalysis gamification framework

Understanding each individual’s motivations is critical to designing learning experiences they’ll connect with. Another way to think about motivators is how Richard Bartle breaks game players into four archetypes: killers, explorers, socialites, and achievers. These might sound familiar from the last game night you had with friends or family (especially if you were playing Monopoly). Someone at the table was absolutely dead set on winning; they’re the killer. And someone else really just wanted to be with everyone and kept losing track of when it was their turn to play; that’s the socialite. The person who was gutted when they didn’t beat their last score or reach a certain game level is the achiever. Last, a fourth player just wanted to get all the way around the board—the explorer.

My team thinks about BJ Fogg’s model, Yu-kai Chou’s motivation drivers, and Bartle’s player types as we seek to understand people’s motivations and how we can provide the right triggers within learning experiences appropriate to 39their ability level. Who are these people? What player type are they? What will motivate them to change their behavior?

Here’s an obvious and classic example of how we bring all this to life at Udemy. In addition to regular performance and career goals, we ask Udemy employees to set learning goals. They can earn raffle tickets for entering their goals into our system, achieving their goals, logging the most learning hours, and other behaviors and milestones. We give out much-coveted raffle prizes, like high-tech suitcases, elaborate fancy-food gift baskets, generous Amazon gift cards, and more. Top learners get a cool hoodie that says, “I’m kind of a big DEAL”—a reference to our Drop Everything And Learn motto. Believe me, people want those hoodies and will work to get one.

Now, that’s all the stuff people immediately think about when they hear “gamification.” People get prizes; this must be a gamified experience. And it’s true that people are motivated by cool prizes; raffles prompt them to engage in order to win, and that’s how we nudge the behavior of continuous learning.

But gamification is also layered far deeper into our instructional design. When we designed our new onboarding course, for example, we used these frameworks to create a fully gamified experience. We designed both a course and an augmented reality experience. The video-based course was just that—not a game at all. But we still thought about player 40types and motivations and ended up building the course as a “choose your own adventure,” where folks could learn what they needed, when they needed it.

Yu-kai Chou’s framework influenced how we built our employee onboarding. We focused on meaning and empowerment as the likely motivation drivers for new employees. With that in mind, the company’s mission and the employee’s role in fulfilling the mission became core themes woven throughout the program. As a result, we saw phenomenal completion rates for the course and significant increases in how quickly new hires achieved productivity.

We also built a game—yes, an actual gamified game. Inspired by Pokémon Go, we created an augmented reality scavenger hunt called Udemy GO that challenged new employees to get into teams and collect knowledge about Udemy. We’ll get into the development process for Udemy GO later, but the socialites and killers were thrilled with this opportunity to win the game and meet new Udemates.

Lesson 7: You Don’t Learn How to Swim in a Library

As lesson 5 pointed out, context is king. When I taught Spanish to Canadian high schoolers, I organized trips to Spain and Cuba for them. It’s one thing to sit in a classroom in Alberta and practice Spanish; it’s a whole other thing to immerse yourself in a culture where Spanish is the prima lingua. I knew this firsthand because I didn’t learn to speak fluently until I had spent time studying in Spain myself.

And, as lesson 1 explained, we don’t learn unless we’re in the position to have spaced repetition and actual on-the-job opportunities to practice. Yet so much of typical corporate learning is event based. This is where we need to follow a communicative-language teaching approach.13 Traveling to Spain didn’t automatically turn my students into Spanish speakers; I had to push them to interact with native speakers to become truly conversational.

You don’t achieve language fluency by learning to conjugate verbs or memorizing vocabulary lists, or my students would have accomplished the same thing back in Alberta. But it’s useful to share the theoretical underpinnings of a subject before sending people off to practice in the real world. My students wanted to be able to do things like read the menu and order a meal in a Spanish restaurant or communicate with new Spanish friends. That’s exactly the practical experience they gained while in Spain.

It’s not all that different with professionals in a work setting. Managers want to know how to delegate effectively, not just talk about frameworks for delegation. Trainers have to find that balance between theory (the “why” behind a particular approach) and practical application (the ability to accomplish things that are relevant and meaningful). Plus, starting with theory will lend credibility to whatever you explain next.

Another thing to keep in mind when you’re teaching working adults is Malcolm Knowles’s theory of andragogy.14 Although I borrow many lessons and insights from my time in the classroom, I have to acknowledge what’s different when it comes to L&D at a company. Knowles studied this and concluded that, when you’re instructing adults:

■ They need to know why they should learn something.

■ They learn by doing (experiential).

■ They see learning as a way to solve problems.

■ They learn best in the moment of need.

• • •

So, yes, we’ve learned a lot about learning, and many in L&D need to unlearn the antiquated ideas and approaches that have soured so many on corporate training. No longer does the L&D instructor possess the knowledge and choose when and how to share it—that is, the “instructivist” model of learning. Today, especially for adult learners, we need to shift to a “constructionist” vision, where learners own and control their experiences, thereby investing themselves personally in the process and retaining more knowledge over the long haul.