Chapter 7

Pulling the Corporate Efficiency Levers

The Six Variables that drive corporate shareholder returns can be grouped into three types of corporate financial efficiency. At a high level, these efficiencies represent the financial levers at the hands of management that will impact future corporate equity returns and shareholder value creation. The three types of corporate financial efficiency are:

- Operating efficiency (O)

- Asset efficiency (A)

- Capital efficiency (C)

Although all three efficiencies are equally important, most businesspeople I know tend to focus on corporate efficiencies in pretty much this order. The V-Formula numerator contains the Six Variables that can pretty much be divided evenly into the three corporate efficiencies.

The formula denominator, being just the percentage of the business funded by equity, is not an added variable; it is just the inverse of the percentage of the business funded by OPM.

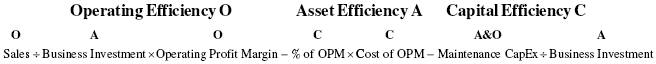

Here is the V-Formula numerator, with each variable labeled with the type of corporate efficiency it represents:

Operating Efficiency (O)

Sales

Corporate operating efficiency begins with sales. A banking adage that I learned at the beginning of my career is this: “No one ever went out of business because they had too many sales.” Sales are the life blood of a business, the first key to corporate operating efficiency, and are effectively simplified in the V-Formula. That's because sales, like all Six Variables, can be expanded upon. An expanded formula for sales might look like this:

The V-Formula is a universal simplification that can be easily expanded. Given the above example, we could eliminate the sales variable altogether, replacing the single variable with the three components that comprise sales above. As we will see in this chapter, each of the Six Variables can be likewise expanded, which would result in a far longer, more complex formula. That said, the math would still be basic middle school math, which is a good thing from the vantage point of most entrepreneurs, since most of us never set out to be math wizards.

Behind the three variables comprising sales is one more: The number of different products you sell. In theory, the bigger your product line, the more customers you might be able to get and the greater the number of products an average customer might buy. You may also be able to charge a higher price for the convenience of having so many products.

Of course, in some cases, reality can be different. For instance, if you are a restaurant operator, more products will require a larger menu. Larger menus increase operating complexity, inventory needs, and likely raise the level of food waste.

In 1988, Wendy's, the nation's third largest fast-food hamburger chain, rolled out its Superbar, which was an expanded salad bar that included salad, fruit, Mexican fare, and even pasta. The idea was to raise customer counts through an expanded product offering. Franchisees were expected to shell out dollars to install the Superbars, which took up space that reduced dining area seating capacity. The effort at product offering expansion turned out to be an operational and gastronomic train wreck. Operators struggled with the elevated labor needs to manage the Superbar. Food costs, which are centered in portion management, were harder to control. So was food waste, which increased due to the need to constantly refresh food bar offerings. In this process, the chain saw its well-earned reputation for quality suffer. Ultimately, this impacted overall same-store sales, operating profitability, and the company's share price. In 1998, after a decade of struggle, the company pulled the Superbars and successfully turned to menu simplification.

The inspiration behind restaurant menu expansion is typically to limit the “veto vote.” Basically, the theory is that broad menu offerings will reduce the possibility that one member of a group—the family on vacation, for example—will express dislike for the menu and compel the group to look elsewhere, thereby losing several sales. But the lesson from Wendy's product expansion efforts is that sometimes it's better not to spend precious money and resources chasing every conceivable sale. Many restaurant chains have successfully implemented product strategies that entail limited offerings. McDonald's and Domino's began that way, and Chick-fil-A and In-N-Out Burger, with four members of the elite 2021 Forbes 400 list of wealthiest Americans among them, are two current examples of restaurant chains that successfully adhere to strategies grounded in limited menu offerings.

Operating Profit Margin

The second corporate efficiency variable is operating profit margin. Part of operating profit margin is simply impacted by the first component of the sales variable, which is product price. Assuming all else equal, if product prices are raised, then the corporate profit margin will go up. In reality, most companies in our competitive economy find they have limited pricing power. But you can see corporate efforts to earn pricing power everywhere. Branding is a clear example. When Daymond John created FUBU, he created a brand that people wanted to own, believing it to be more valuable. The sleek, appealing designs offered by Apple have long made its products aspirational, enabling comparatively higher pricing and elevated profit margins. Likewise, retailers often have private label merchandise affixed with their logos to elevate pricing power through branding and the appearance of scarcity (you can't find the exact same merchandise anywhere else). Unquestionably, aspirational luxury goods makers have invested a great deal in elevating brand awareness that confers pricing power.

Most business efforts to elevate profit margins involve cost control. If you are selling a retail or manufactured product, you might first look at managing your cost of goods sold. For many companies, this is their single largest cost. Walmart, the world's single largest retail chain, with annual revenues exceeding $500 billion annually as of January 2020, operates on notoriously thin margins. Between their fiscal years ending January 31, 2017, and January 31, 2020, gross profit margins (this is simply equal to [sales – cost of goods sold] ÷ sales) approximated 25%. No doubt, a great deal of effort is expended by the company to reduce its cost of goods sold and thereby elevate its gross profit margins. The sum of Walmart's operating and general and administrative costs amounted to about 21% of sales, or less than a third of their cost of goods sold. Doubtless, the company had initiatives in place to manage these costs also. That would be natural because their net income margin (reported net income divided into sales) averaged below 2% between 2017 and 2020. This kind of statistic makes Walmart a poster child for high volume, low margin companies. With profit margins this low, if you think you are getting a good deal at Walmart, you generally are.

As we discussed earlier in Chapter 4, operating profit margin is simply EBITDAR as a percentage of sales. However, in keeping with the thought that V-Formula variables are each expandable to elevate detail, a high-level formula for operating profit margin for Walmart might look like this:

Consistent with our financial approach, within the definition of EBITDAR (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and rents), non-cash accounting conventions like depreciation and executive stock compensation are excluded from the formula. Also, lease costs for assets that might otherwise have been purchased are frequently included in operating expenses. I remove these costs as I try to make a more accurate assessment of the percentage of a company funded by OPM.

However, it should be clear by now that you can make this operating profit formula as long as you wish. You can break out specific goods costs or specific operating and general and administrative expenses. You might choose to do this to note the large costs that bear the most attention. By making single variable formulas for sales or operating profit margin into multiple variables, the simplified universal business model that is the V-Formula becomes far more tailored.

Asset Efficiency (A)

Business Investment

Asset (or business investment) efficiency is simply the notion of working to make your business investment as low as possible. All else equal, the less money tied up in business investment, the better. If you are operating the restaurant in our case study, you might attempt to see if you can construct the restaurant for less. I have helped finance thousands of restaurant properties and have occasionally seen companies desiring to build expensive monuments to gastronomy when smaller, more efficient facilities will do. Overbuilding requires little talent. Rather, the talent lies in crafting prudent construction budgets that deliver well-built facilities looking like you spent more than they cost. Or you might see if you can rent another property cheaply enough to represent an effective price discount over the cost of new construction. In such a case, you might even see if your landlord would pay for most or all the necessary conversion costs.

While the business investment of restaurant companies tends to be dominated by real estate, furniture, fixtures, and equipment costs, other business models entail significant investments in working capital assets, which include accounts receivable, inventory, and prepaid and deferred costs. This is especially so for manufacturing companies like FUBU or Apple, which tend to have every type of working capital asset imaginable. Retailers like Walmart will likewise have lots of dollars invested in inventory, but tend to have little in the way of accounts receivable; their customers pay by cash or credit card, which means that retailers tend to experience minimal delay between the time they sell their merchandise and the time they are paid for it.

What follows is a basic formula for the business investment V-Formula variable. As with the sales and operating profit margin variables, you can expand this variable to include the “hard asset” variables as well as a myriad of “working capital” variables that collectively comprise business investment. In this way, a universal business variable (business investment) can be custom-tailored to your business.

In our global economy, supply chain management has become a specialization and is at the heart of business efforts to limit their amount of working capital by speeding up the cash flow cycle. (You may recall Daymond John's initial onerous 240-day revenue cycle.) Inventory can be maintained at low levels through restocking strategies that entail inventory that is delivered “just in time.” Terms of customer accounts receivable can be shortened. Requirements for the prepayment of inventory or services can be limited. Vendor accounts payable terms can be lengthened. Customer deposits can be requested on orders. Indeed, there are a lot of working capital levers that can be addressed. Not surprisingly, given the increased level of attention to working capital demands, your efforts to reduce working capital will conflict with similar incentives on the parts of your suppliers and the businesses you sell to.

Supply chain management and a global economy have contributed to advances in business model efficiency. Perhaps the biggest of these is for companies to elect “asset-light” operating models. Think of Apple, where merchandise labels note that devices are “designed by Apple in California,” but made globally through a sophisticated supplier network. As a result, Apple has fewer requirements for real estate, furniture, fixtures, and equipment, which lowers their business investment needs and trades off high levels of associated fixed operating costs for variable production costs. Likewise, clothing manufacturers such as FUBU have the potential to limit their expenditures to the design elements of their business, outsourcing production and distribution. Through such efforts, the aim is to achieve a business model requiring less cash to create, resulting in less OPM and less YOM while delivering a high level of scalability and the potential for elevated equity returns and wealth creation.

Operating leverage is the ability to materially grow sales without similar added investments in hard assets. Operating leverage tends to be a common characteristic of companies capable of high levels of EMVA creation. Still, even with such companies, working capital business investment requirements will tend to rise commensurately with sales. For working capital intensive businesses, the downside of sales growth is a loss of cash that might otherwise have been used for other investments or contemplated investor cash distributions. How much can sales grow before you need additional equity infusion to support working capital? The answer is approximately the same sales growth as your current rate of after-tax current equity returns, which is also what is called your “sustainable growth rate.” Here, it's worth noting that added working capital business investment can be driven by either real or inflationary sales growth, which serves as a reminder of the destructive impacts of inflation.

Early on in my banking career, I recall looking at a successful Latin American retailer based in a country having a very high rate of inflation at the time. The resultant working capital growth left the company in a cash trap requiring continued inflation-driven business investment producing no real added value. For working capital intensive companies, added business investment will accompany sales growth, whether it is real of inflationary.

Notably absent from the computation of business investment are research and development (R&D) costs, which are central to technology-centric companies. Without question, R&D activities are absolutely an investment in the future, but they are typically not shown as balance sheet assets. They are instead expensed, impacting operating profit margins and operating efficiency, as opposed to business investment and asset efficiency. This characterization can potentially serve to understate equity rates of return, assuming you believe your R&D costs to be investments having real long-term value that will translate into future revenues.

In a nutshell, that is what business investment is: Assets essential to revenue creation that are funded by OPM and equity. Therefore, in determining your V-Formula, you might consider the inclusion of R&D costs as a business investment while removing them from operating expenses. Or you can take a more conservative approach by including R&D costs as operating expenditures, which will serve to compress your operating profit margin and lessen calculated equity returns.

Choosing how to best incorporate R&D costs into your current equity return analysis mirrors accounting imperfection. On the one hand, GAAP demands that R&D costs be expensed when they are made. On the other hand, when a company having made such R&D investments is acquired by another company, it is acceptable to capitalize the proven value of trademarks and patents into business investment. In other words, the accounting profession permits capitalization, but only in the context of an acquisition after the R&D expenses have demonstrated their long-term value.

Maintenance CapEx

Within the V-Formula, there is one other variable that impacts both asset and operating efficiency. That variable is the amount paid annually for maintenance capex. Regular maintenance capex is simply the amount you spend on hard assets annually to maintain the existing business you have. If you elect to include R&D costs in your definition of business investment, you would then include any replacement R&D costs in your annual maintenance capex costs to maintain product relevancy. Typically, businesses will expend far more on R&D or hard asset investments than just annual capital maintenance capex, but much of this will be in the form of expansion-related investments, which is an added form of business investment. We will discuss funding added business investment in a later chapter.

When it comes to the notion of maintenance capex, I tend to include two other forms of annual expenditure. The first of these is what I call periodic remodeling costs, which are mostly evident in consumer-facing businesses. Every five years or so, retailers, hotel operators, fitness clubs and many more businesses will undergo a reimaging or remodeling to maintain an up-to-date look and feel of the business. Without such periodic extensive remodeling, consumer-facing businesses generally risk the loss of customers to competing businesses boasting a better appearance. Hence, if you are in such a business, you should factor into your annual maintenance capex variable the average annual cost of a more material periodic reinvestment requirement.

In addition to the cost of periodic extensive remodels, I might also include the costs associated with poor decisions. Throughout most of my career, I have worked extensively with multilocation consumer-facing businesses. One lesson I have learned from this is the amount of sales generated by each location seldom correlates to the cost to construct that location. As a result of this unpredictability, there tends to be a location failure rate that will exact a cost on the business model. Nearly every well-known multilocation, consumer-facing company has experienced location closures. Sometimes such closures arise from facility relocation, in which case the losses from old location dispositions are probably best included as an addition to the cost of business investment for the replacement location. Even the best retailers suffer periodic store relocations and closures. During 2016, Walmart closed nearly 300 locations. Some years before that, the company's growth strategy entailed the development of larger Walmart Supercenters, together with the closure and divestiture of older, smaller store prototypes.

Of course, business investment failures are not simply associated with multilocation consumer facing retail and service companies. Technology companies will likewise occasionally light R&D money on fire. And companies seeking to expand through M&A activity invariably will make some poor investments.

Maintenance capex is not generally the most material variable within the V-Formula. However, it can highlight business investment tradeoffs. At a basic level, those tradeoffs could be between the hard asset portion of business investment and the cost to maintain those very assets over time. Or there can be tradeoffs between corporate expansion strategies requiring new business investment and the potential wealth destruction risks of poor decisions.

Capital Efficiency (C)

OPM Variables

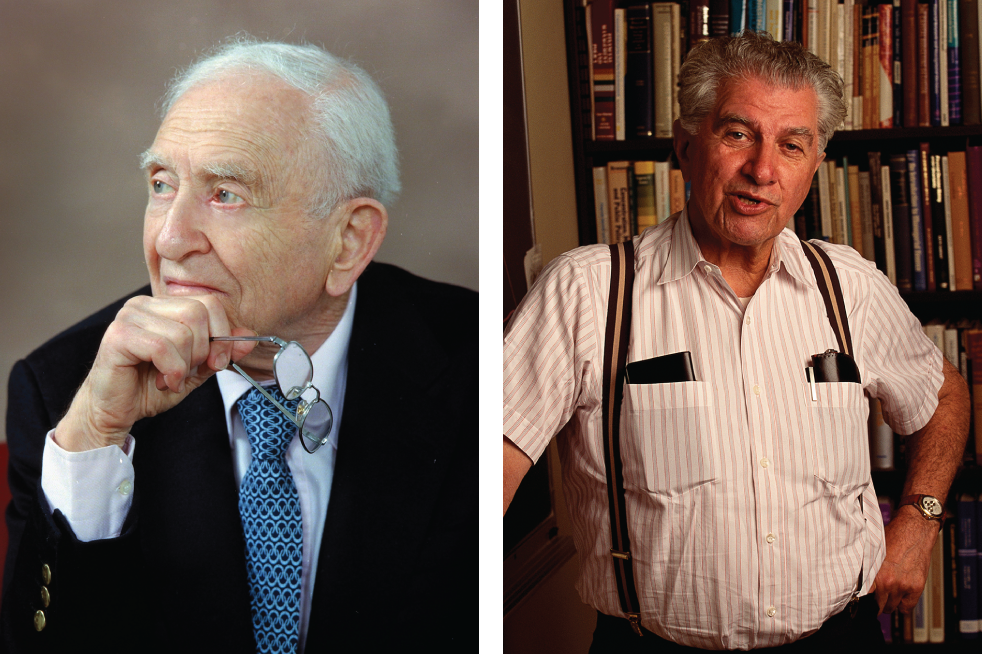

Cost of capital refers to the weighted cost of equity and OPM. The idea is that, by achieving the lowest cost of capital, the company will be worth more, and shareholders (company founders and early investors foremost) will be the beneficiaries. The logic sounds circular, since a higher mix of OPM will raise equity returns while potentially elevating corporate risk through higher leverage, which can raise the cost of equity. This is why Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller, while they were professors at Carnegie Mellon University in 1958, developed what is often called the “Capital Structure Irrelevance Principle,” which essentially stated that varying mixes of OPM and equity would have no impact on corporate valuations. The theorem would contribute to their eventual recognition by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which in 1985 awarded Modigliani the Nobel Prize in Economics, and then in 1990 the same prize for Miller.

Key theorem assumption exclusions included taxes and transaction costs and included the assumption that individuals and corporations borrow money at the same rates. In the real world, these limitations are violated constantly. Tax considerations are frequent, individuals and companies do not borrow at the same rates, and OPM is hardly a consistent commodity for the vast number of private American businesses.

1985 Nobel Laureate Franco Modigiani and 1990 Nobel Laureate Merton Miller, creators of the “Capital Structure Irrelevance Principle”

Credit: Bachrach/Archive Photos/Getty Images

Credit: Ralf-Finn Hestoft/Corbis Historical/Getty Images

A company's cost of capital can be lowered in many ways. Diversified loan conduits, which are basically pools of loans sold to fixed-income investors, can enable businesses to borrow at investment-grade rates, even though they might not otherwise be corporately rated BBB– or higher, which is the definition of investment-grade. This technology is akin to the ability of the average American to obtain a low-cost home mortgage because of the diversity of residential mortgage loan pools and the perceived safety of residential real estate. The availability of tools like loan conduits or whole business securitizations, whereby valuable corporate assets are pledged in the process of investment-grade debt issuance, is one reason that comparatively few companies globally bother to have investment-grade corporate credit ratings. Likewise, preferred stocks, convertible debt, and convertible preferred shares are sophisticated forms of OPM, often delivered by investors having an ability to offer competitive capital pricing enabled by diversification. Corporate real estate locations, aircraft, and other long-term assets can be efficiently leased rather than owned. The most recent company I co-founded, STORE Capital, provides such services for real estate. While leasing tends to have a higher cost than borrowing, lease solutions can lower capital costs because they enable the use of less shareholder equity. At the same time, leasing tends to free up cash flow, because it has amongst the lowest payment constants available with long-term OPM. This is because leasing companies are often not expecting you to repay the proceeds used to acquire the property and are willing to undertake residual ownership risk.

Leasing companies, especially those that lease equipment, often derive tax benefits from their property ownership, which can contribute to the efficiency of this type of OPM. Beyond this, leasing solutions can often serve to deliver more financial flexibility, which is also highly important in determining your optimal capital stack. Corporate flexibility is essential to avoid opportunity costs, which are essentially corporate activity limitations that have the potential to exact a price. Opportunity costs are an important business consideration and will be discussed later in greater detail.

Since the Modigliani-Miller theorem—the Capital Structure Irrelevance Principle—was conceived in 1958, capital markets have advanced greatly, and companies like STORE have emerged with the promise of effecting lower corporate costs of capital. The Capital Structure Irrelevance Principle fundamentally posited (with important assumption limitations) that there is no free lunch. However, it turns out that the theorem's limiting assumptions are not limited in the real world, meaning that there actually is free lunch to be had. It's up to business leaders to uncover such opportunities, and thereby raise equity returns and wealth creation potential.

Six-Shot Economics

The Six Variables in the V-Formula can be apportioned between a company's operating, asset, and capital efficiencies. In turn, those Six Variables can be expanded to include 30 or more variables, raising the complexity of the V-Formula as you tailor it to your enterprise. I have historically referred to the six basic financial efficiency levers as “Six-Shot Economics,” being broadly the universal financial tools at the hands of business leadership that offer six shots to elevate equity returns and wealth creation.1

Six-Shot Economics is driven by constant innovation. Within a highly competitive global marketplace, the pace of innovation places greater demands upon business leaders and their teams to constantly modify their six efficiency levers.

Like any economic concept, the implications of Six-Shot Economics span from the micro corporate level to macro implications for economies as a whole. As business leadership takes more shots at corporate efficiencies, the impact of these collective efforts across millions of businesses is bound to contribute to improved economic growth, accompanied by elevated productivity and controlled inflation. So, more than just a financial toolkit for business leaders, Six-Shot Economics contributes meaningfully to our overall prosperity and economic health.

Note

- 1. I introduced the notion of Six Shot Economics in the December 2007 issue of Strategic Finance, published by the Institute of Management Accountants.